Abstract

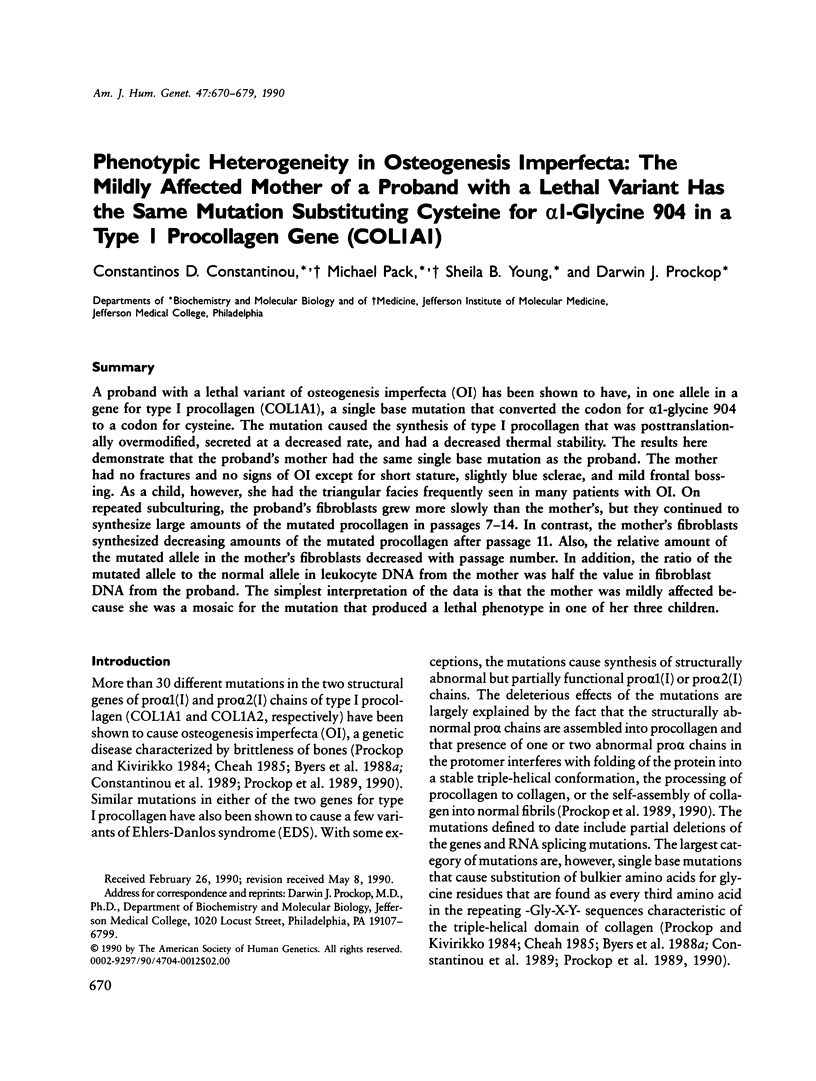

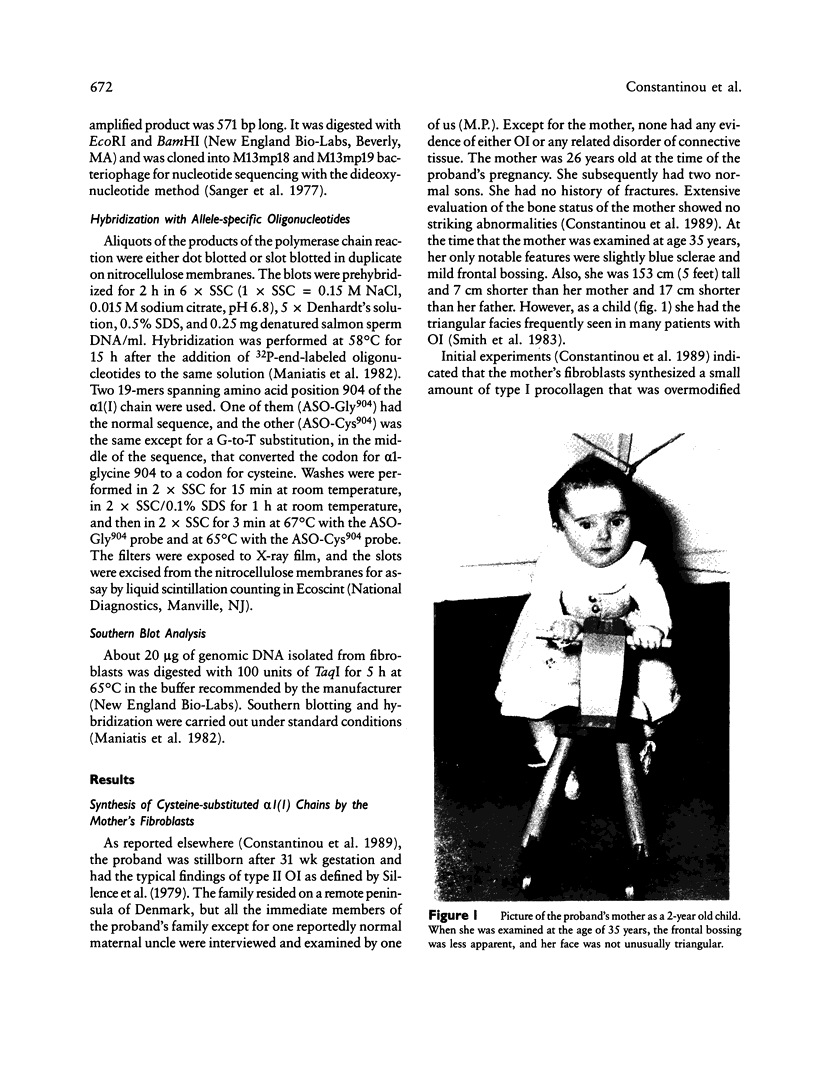

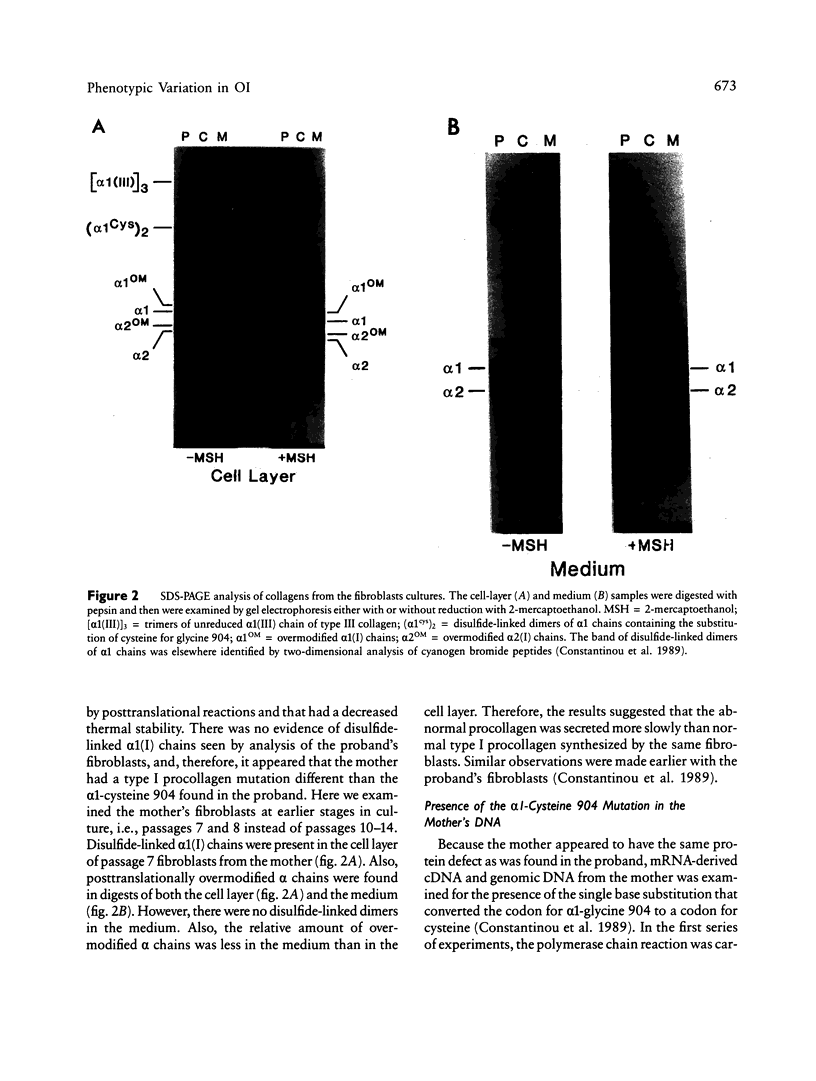

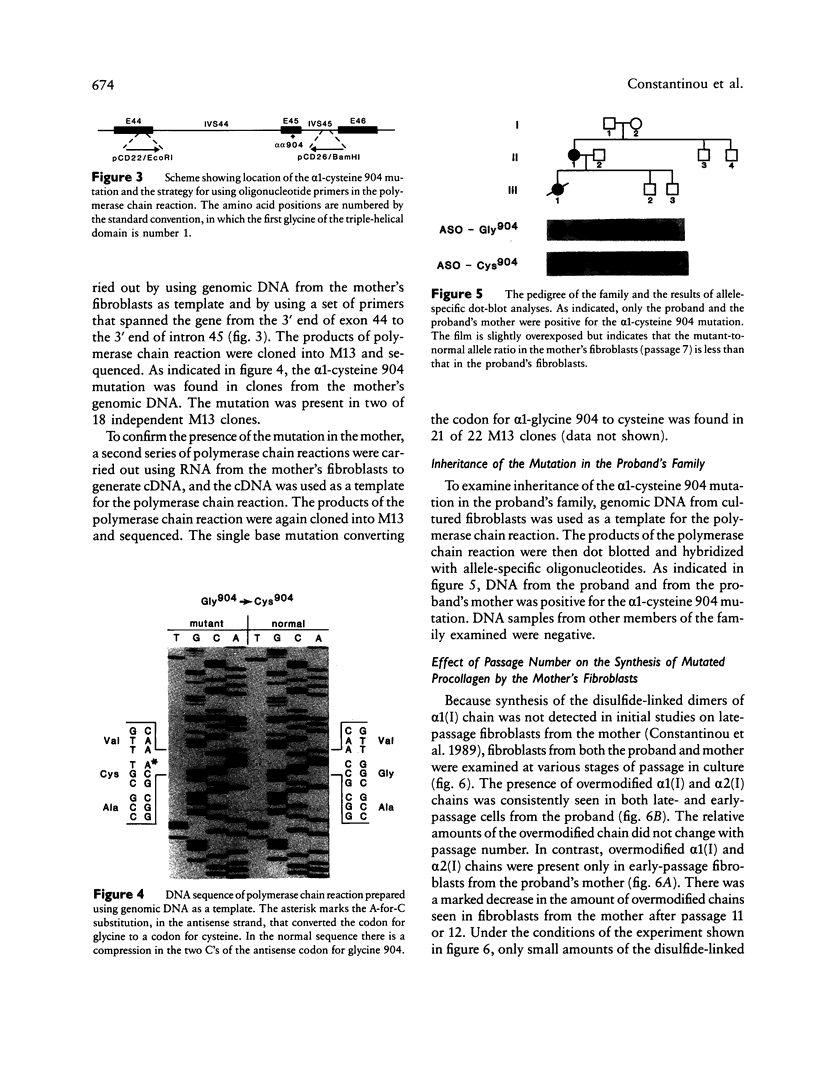

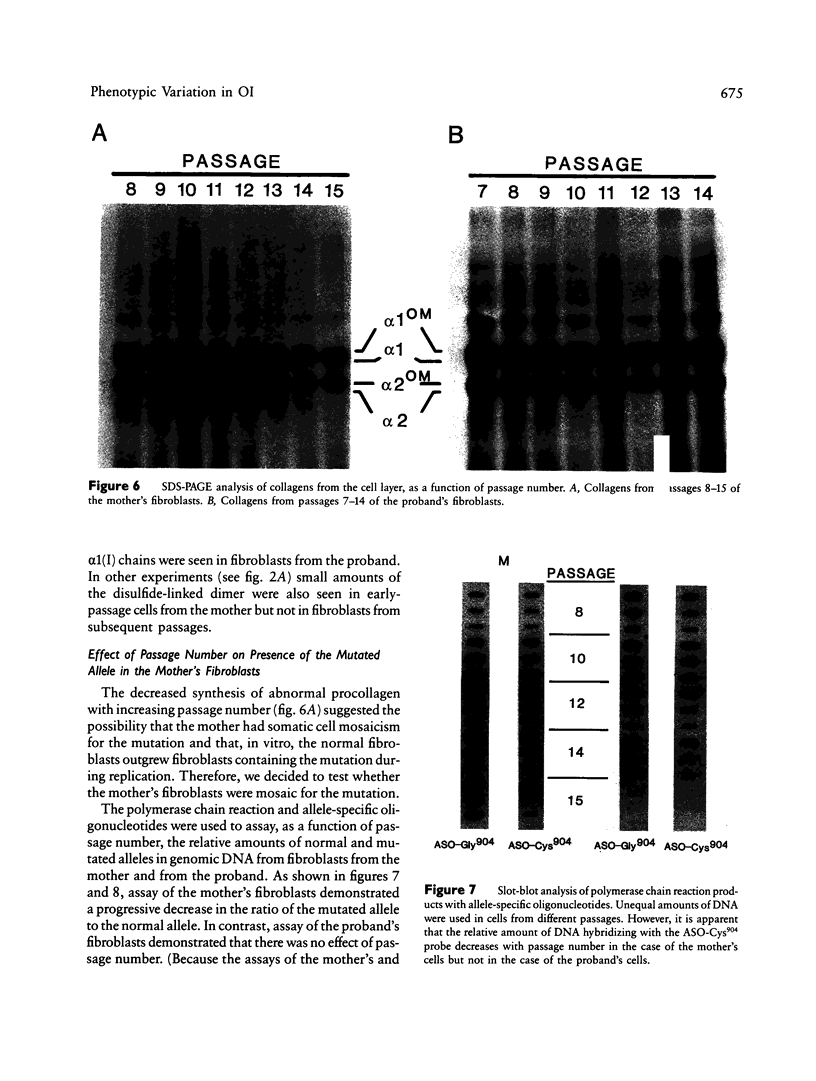

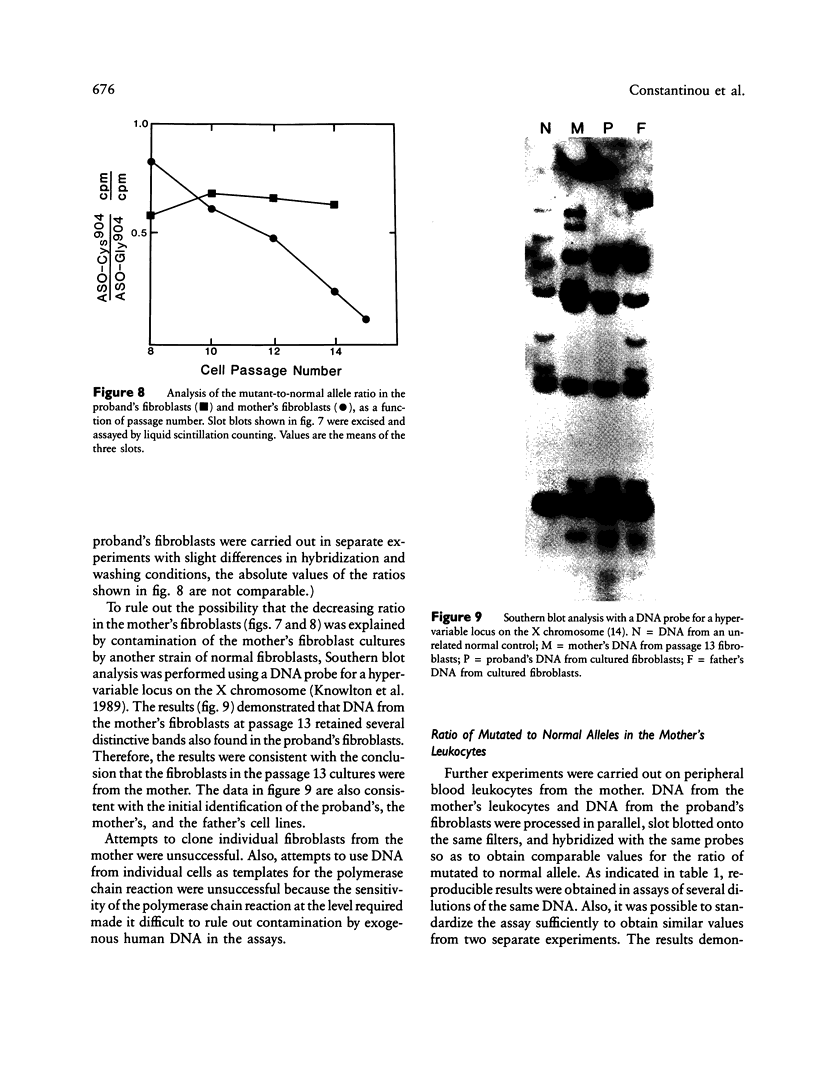

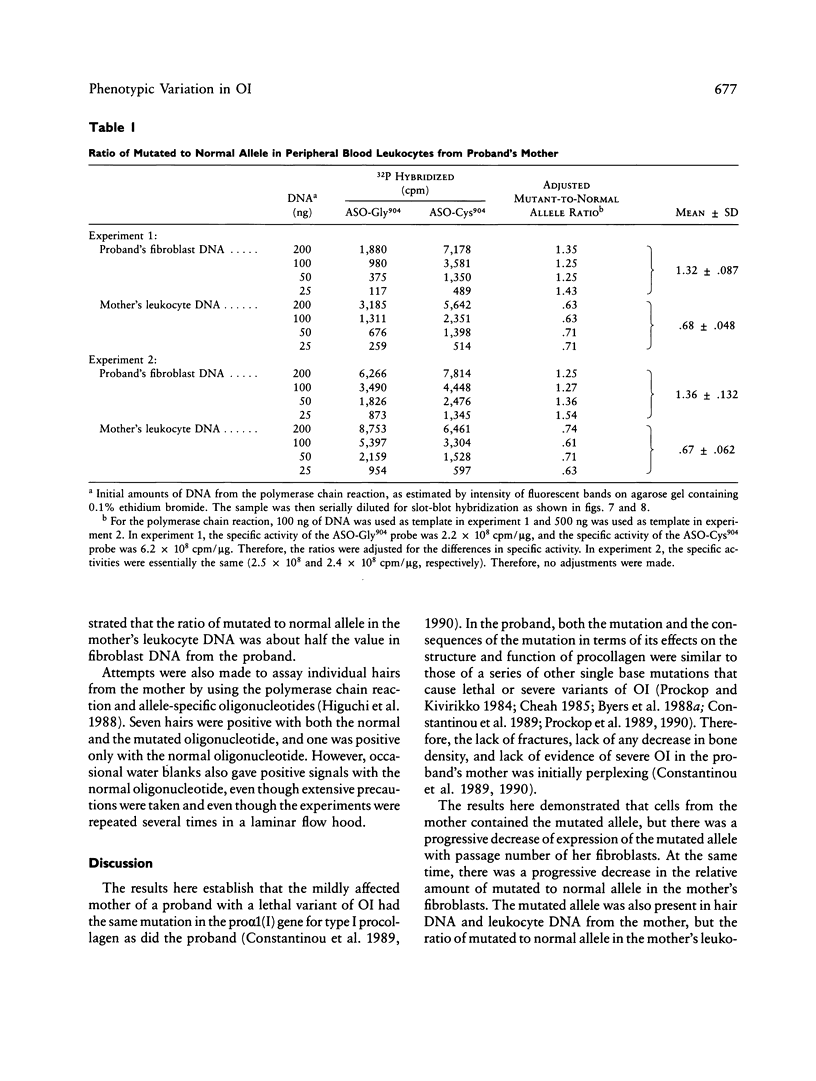

A proband with a lethal variant of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) has been shown to have, in one allele in a gene for type I procollagen (COL1A1), a single base mutation that converted the codon for alpha 1-glycine 904 to a codon for cysteine. The mutation caused the synthesis of type I procollagen that was posttranslationally overmodified, secreted at a decreased rate, and had a decreased thermal stability. The results here demonstrate that the proband's mother had the same single base mutation as the proband. The mother had no fractures and no signs of OI except for short stature, slightly blue sclerae, and mild frontal bossing. As a child, however, she had the triangular facies frequently seen in many patients with OI. On repeated subculturing, the proband's fibroblasts grew more slowly than the mother's, but they continued to synthesize large amounts of the mutated procollagen in passages 7-14. In contrast, the mother's fibroblasts synthesized decreasing amounts of the mutated procollagen after passage 11. Also, the relative amount of the mutated allele in the mother's fibroblasts decreased with passage number. In addition, the ratio of the mutated allele to the normal allele in leukocyte DNA from the mother was half the value in fibroblast DNA from the proband. The simplest interpretation of the data is that the mother was mildly affected because she was a mosaic for the mutation that produced a lethal phenotype in one of her three children.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Byers P. H., Bonadio J. F., Cohn D. H., Starman B. J., Wenstrup R. J., Willing M. C. Osteogenesis imperfecta: the molecular basis of clinical heterogeneity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;543:117–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb55324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers P. H., Tsipouras P., Bonadio J. F., Starman B. J., Schwartz R. C. Perinatal lethal osteogenesis imperfecta (OI type II): a biochemically heterogeneous disorder usually due to new mutations in the genes for type I collagen. Am J Hum Genet. 1988 Feb;42(2):237–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah K. S. Collagen genes and inherited connective tissue disease. Biochem J. 1985 Jul 15;229(2):287–303. doi: 10.1042/bj2290287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinou C. D., Nielsen K. B., Prockop D. J. A lethal variant of osteogenesis imperfecta has a single base mutation that substitutes cysteine for glycine 904 of the alpha 1(I) chain of type I procollagen. The asymptomatic mother has an unidentified mutation producing an overmodified and unstable type I procollagen. J Clin Invest. 1989 Feb;83(2):574–584. doi: 10.1172/JCI113920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring S. R., Stephenson M. L., Downie E., Krane S. M., Korn J. H. Heterogeneity in hormone responses and patterns of collagen synthesis in cloned dermal fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1990 Mar;85(3):798–803. doi: 10.1172/JCI114506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodship J., Malcolm S., Lau Y. L., Pembrey M. E., Levinsky R. J. Use of X chromosome inactivation analysis to establish carrier status for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Lancet. 1988 Apr 2;1(8588):729–732. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. G. Review and hypotheses: somatic mosaicism: observations related to clinical genetics. Am J Hum Genet. 1988 Oct;43(4):355–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happle R. Lethal genes surviving by mosaicism: a possible explanation for sporadic birth defects involving the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987 Apr;16(4):899–906. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)80249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi R., von Beroldingen C. H., Sensabaugh G. F., Erlich H. A. DNA typing from single hairs. Nature. 1988 Apr 7;332(6164):543–546. doi: 10.1038/332543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton R. G., Nelson C. A., Brown V. A., Page D. C., Donis-Keller H. An extremely polymorphic locus on the short arm of the human X chromosome with homology to the long arm of the Y chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989 Jan 11;17(1):423–437. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.1.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz B., Gearhart J. D., Guymont A. O. Phytohemagglutinin-mediated blastomere aggregation and development of allophenic mice. Dev Biol. 1973 Mar;31(1):195–199. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(73)90331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop D. J., Constantinou C. D., Dombrowski K. E., Hojima Y., Kadler K. E., Kuivaniemi H., Tromp G., Vogel B. E. Type I procollagen: the gene-protein system that harbors most of the mutations causing osteogenesis imperfecta and probably more common heritable disorders of connective tissue. Am J Med Genet. 1989 Sep;34(1):60–67. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320340112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop D. J., Kivirikko K. I. Heritable diseases of collagen. N Engl J Med. 1984 Aug 9;311(6):376–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop D. J., Olsen A., Kontusaari S., Hyland J., Ala-Kokko L., Vasan N. S., Barton E., Buck S., Harrison K., Brent R. L. Mutations in human procollagen genes. Consequences of the mutations in man and in transgenic mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;580:330–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb17942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi V. M., Lewis R. A. Penetrance of von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis: a distinction between predecessors and descendants. Am J Hum Genet. 1988 Feb;42(2):284–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUN-SHIN M. Congenital web formation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954 May;36-B(2):268–271. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.36B2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiki R. K., Scharf S., Faloona F., Mullis K. B., Horn G. T., Erlich H. A., Arnheim N. Enzymatic amplification of beta-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science. 1985 Dec 20;230(4732):1350–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.2999980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillence D. O., Senn A., Danks D. M. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 1979 Apr;16(2):101–116. doi: 10.1136/jmg.16.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P., Jaenisch R. Retroviruses as probes for mammalian development: allocation of cells to the somatic and germ cell lineages. Cell. 1986 Jul 4;46(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90856-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie T. M., Brinster R. L., Palmiter R. D. Germline and somatic mosaicism in transgenic mice. Dev Biol. 1986 Nov;118(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]