Abstract

Fungi produce a plethora of secondary metabolites yet their biological significance is often little understood. Some compounds show well-known antibiotic properties, others may serve as volatile signals for the attraction of insects that act as vectors of spores or gametes. Our investigations in an outcrossing, self-incompatible fungus show that a fungus-produced volatile compound with fungitoxic activities is also responsible for the attraction of specific insects that transfer gametes. We argue that insect attraction using this compound is likely to have evolved from its primary function of defence—as has been suggested for floral scent in the angiosperms. We, thus, propose that similar yet convergent evolutionary pathways have lead to interspecific communication signals in both fungi and plants.

Keywords: Epichloë, volatiles, scent, fly pollination

1. Introduction

Many fungi depend on insects for the dispersal of spores, which serve either as propagules or gametes for fertilization. The latter function is analogous to pollination in plants, and for ‘pollinator’ attraction, some fungi produce showy flower-mimics with sugar rewards, that are visited by a range of pollinator insects (Roy 1993; Roy & Raguso 1997). Other fungi attract only a few, specific pollinators, primarily by olfactory signals. Such a specialized relationship is found in endophytic fungi of Epichloë (Clavicipitaceae, Ascomycota), which systemically infect pooid grasses where they develop an external fruiting structure, the stroma, for sexual reproduction (Schardl et al. 2004). Epichloë spp. are self-incompatible, and sexual ascospores are only formed if gametes (conidia) of one mating type are transferred to stromata of the opposite mating type. Fungal stromata specifically attract female flies of the genus Botanophila (Anthomyiidae) that actively cross-fertilize and then oviposit on the fungus (Bultman et al. 1998). Hatching larvae consume part of the fungal tissues, which produce ascospores, but enough is left for reproduction as excessive exploitation of the fungus is prevented by greater larval mortality with increasing egg load (Bultman et al. 2000). Since fly larvae depend on fertilized stroma as food source, both fly and fungus clearly profit from this mutualistic association. The grass host, in turn, benefits from the fungus-produced secondary metabolites that may provide increased resistance to herbivores or pathogens (Shimanuki 1987; Breen 1994; Brem & Leuchtmann 2001).

We investigated the chemical communication in the specialized Epichloë–Botanophila relationship and provide an intriguing link between the antimicrobial function of a secondary metabolite and the attraction of gamete vectors in this fungus. We collected volatiles from Epichloë fungal stromata of two species and analysed the samples by gas chromatography coupled with electroantennographic detection (GC–EAD) to detect compounds that are physiologically active in the flies' olfactory neurons, and conducted bioassays to investigate the behavioural activity of the EAD-active compounds.

2. Material and methods

(a) Fungi, plants and insects

For volatile collection Epichloë typhina infecting Anthoxanthum odoratum (two genotypes), and Epichloë sylvatica infecting Brachypodium sylvaticum (six genotypes) were used. Infected plants were grown in pots maintained outdoors at the Botanical Garden Zürich. Female Botanophila flies used for EAD were collected with hand nets while visiting Epichloë stromata of infected A. odoratum plants. Females of these flies are virtually impossible to identify by morphological traits. Thus, we are as yet unable to assign species names to the specimen caught. Flies, however, were identified by molecular markers based on sequence analysis of the mitochondrial protein coding gene cytochrome oxidase (COII), and comparison of sequences with those from previously identified Epichloë-associated Botanophila (Leuchtmann 2005).

(b) Chemical and electrophysiological analysis

Volatiles were collected from freshly emerged, unfertilized fungal stromata by headspace sorption (Huber et al. 2005); samples for structure elucidation were collected by rinsing 30×10 stromata in 2 ml dichloromethane for two minutes and pooling the samples. Until use, all samples were stored in a freezer at −20 °C. For GC–EAD the GC was equipped with a HP5 column (30 m×0.32 mm internal diameter (i.d.)×0.25 μm film thickness) and a flame ionization detector (FID); helium was used as carrier gas. One microlitre of each sample was injected splitless at 50 °C (1 min) into a GC (Agilent 6890N) followed by opening the split valve and programming to 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1. For EAD recording, heads of individual flies were cut off and mounted on a grounded glass electrode filled with insect ringer solution and mounted on a micromanipulator. A second glass electrode (recording electrode) was connected to the tip of the funiculus of one of the flies' antenna; the arista of this antenna was cut off at its base.

(c) Structural assignment

Analysis by coupled GC/mass spectrometry (MS) (double focusing instrument VG 70-250 S, Vacuum Generators, Manchester, UK, separation conditions as above) indicated the active compound to have a molecular weight of M=222. Chemical ionization (isobutane) as well as high-resolution MS revealed a molecular formula of C15H26O (three double bond equivalents). Loss of water (m/z 204) and a most abundant signal at m/z 69 suggested a sesquiterpene alcohol with a β,β-dimethylallyl group as a substructure. Mass spectra and retention times of the active compound were identical in E. typhina and E. sylvatica. Published data on the mass spectrum of the sesquiterpene alcohol chokol K, identified from E. typhina (Tanimori et al. 1994) were in good accordance with our mass spectrum.

From the dichloromethane-extract of 350 stromata of E. sylvaticum, the biologically active compound could be isolated by preparative GC. The device consisted of a HP 5890 GC, an autosampler HP 7673 (both Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto CA, USA) and a fraction collector (Gerstel, Mülheim, Germany). The isolation was carried out by using a 30 m, 0.53 mm i.d. fused silica capillary Optima 5, film thickness 1 μm (Macherey & Nagel, Düren, Germany). Hydrogen served as the carrier gas. For NMR-investigations of the isolated compound, dissolved in CDCl3, a DRX-500 instrument (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used. The sets of data obtained with 1H-NMR-, HMBC-, HMQC- and NOE-experiments were in full accord with those published for chokol K (Trost & Phan 1993; Tanimori et al. 1994). In hexane, the natural product showed a negative rotation value, as in an ethanolic solution of natural chokol K (Koshino et al. 1989; Trost & Phan 1993). Upon enantioselective GC (25 m, 0.25 mm i.d. fused capillary column coated with a 1 : 1 mixture of OV1701 and heptakis (2,3-di-o-acetyl-6-o-tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-β-cyclodextrin, isothermal at 110 °C), racemic chokol K could be well resolved (rt (−)=42.2 min, α=rt (−) : r (+)=1.0374). GC investigations on natural extracts revealed chokol K from E. sylvaticum and E. typhina to be the (1R,2S,3R)-stereoisomer (Trost & Phan 1993), showing an enantiomeric purity of at least 98% enantiomeric excess.

(d) Synthesis of chokol K

The synthesis of racemic chokol K (1R*,2S*,3R*)-1,2-dimethyl-3-(6-methylhepta-1,5-dien-2-yl) cyclopentanol was carried out by employing a modification of the procedure of Tanimori et al. (1994; see electronic supplementary material). The synthetic product, a colourless oil, was purified by chromatography (silica gel, pentane/Et2O 1 : 1) and bulb-to-bulb distillation (55 °C, 10−2 Torr). Spectroscopic data (IR, NMR and MS) of the product were found to be in complete accordance with published data (Tanimori et al. 1994).

(e) Bioassays

To test the electrophysiologically active compound for behavioural activity, attraction experiments with sticky traps were carried out at the Botanical Garden Zürich (Huber et al. 2005). The traps consisted of a white plastic disc 8 cm in diameter to which insect glue was applied (commercial insect exclusion adhesive; Temmen Insektenleim, Hattersheim) and covered with a plastic bowl. Synthetic, racemic chokol K (0.1; 1; 10 mg) was applied on a small rubber GC septum placed in the middle of a plastic disc. Release rates of volatiles from the septa were controlled for and found to be in the range of equal to three times as much as one intact stroma (data not shown). Traps were set up in grassland near the Botanical Garden where no Epichloë-infected grasses occurred within a radius of 100 m. A chi-square test was used to compare the frequency of flies attracted to ‘chokol’- and control traps.

3. Results

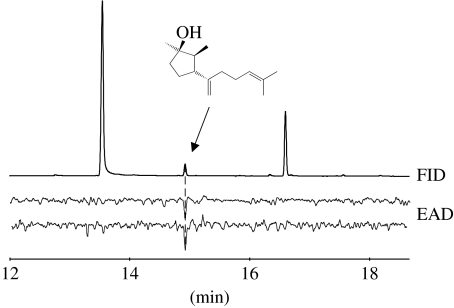

In all GC–EAD recordings, one substance proved to be active (figure 1), which was identified as the sesquiterpene alcohol chokol K, previously known as a fungitoxic compound from Epichloë (Koshino et al. 1989). Epichloë typhina emitted chokol K from fungal stromata on infected grass culms (table 1), as well as from pure, cultured mycelium on agar medium (Steinebrunner 2005, unpublished data), confirming the fungal origin of the compound (Koshino et al. 1989).

Figure 1.

Gas chromatographic analysis with flame ionization detector (FID) of Epichloë typhina stromata-extract and simultaneous electroantennographic detection (EAD) using heads of Botanophila flies caught from E. typhina stromata. Chokol K triggered consistent EAD responses in analyses with three fly individuals. The major, non-active components eluting before and after chokol K are coumarin and methyl 2,3-dihydrofarnesenoate, respectively.

Table 1.

Amounts of chokol K emitted from Epichloë stromata on plant host.

| Epichloë species | headspace (ng l−1) | pooled extract (ng stroma−1) |

|---|---|---|

| E. typhina | 82.37±58.86 | 18.1 |

| E. sylvatica | 50.72±42.05 | 240.5 |

The pollinator attracting function of chokol K was demonstrated in field bioassays where 11 Botanophila flies were caught on traps emitting synthetic chokol K, whereas no Botanophila were caught on control traps treated with solvent only during five subsequent days (χ2=8.33; p=0.004). On both types of traps, however, several unrelated insects (mostly dipteran) were also present. Botanophila flies were identified by molecular markers and 10 individuals matched with those previously known to visit and fertilize stromata of E. typhina and E. sylvatica. One individual belonged to a Botanophila taxon not found previously on these hosts. The attractiveness of the traps corresponded well to natural stromata, as not more than three Botanophila individuals per hour may typically visit stromata of an infected grass clump with warm weather under field conditions (Leuchtmann 2004, personal observation) indicating that fly visitation frequency is rather low. These results suggest that chokol K is a key compound in the attraction of Botanophila flies to Epichloë stromata. In addition to its pollinator attracting function, chokol K, as well as several other chokols produced by Epichloë species, has fungitoxic properties (Koshino et al. 1989; Tanimori et al. 1994).

4. Discussion

Antagonistic interactions among fungi are common, and fungal secondary metabolites with antimicrobial functions are known since long, the most famous example being the powerful antibiotics produced by Penicillium chrysogenum (Fleming 1929). Recently, volatile compounds with inhibitory effects on a range of micro-organisms were discovered in endophytic species of Muscodor and Gliocladium (Strobel et al. 2001; Stinson et al. 2003). Generally, volatile compounds are better known as signal transmitters in intra- and interspecific communication, and are important for pollinator attraction in many higher plants (Raguso 2001). In fungi, dependent upon insects for gamete transfer, odour signals can mediate the attraction of insects. For example, in some endophytic rust fungi, pollinator attracting volatile compounds emitted from infected plant parts have been identified (Connick & French 1991; Raguso & Roy 1998; Naef et al. 2002). It is, however, often not clear whether the fungi produce the volatiles de novo, or use plant precursors, or induce emission of volatiles upon infection.

Our data provide evidence that a single fungal volatile is attractive to a specific pollinator insect. Interestingly, this compound has a dual function by also inhibiting other fungi that may secondarily infect the fungal stromata, posing the question of which role evolved first. Although phylogenetic analyses, useful to answer this question, are not yet available, we assume that antibiotic compounds are evolutionarily ancient among fungi, because resistance to competitors and parasites is a basic need for most soil and plant inhabiting fungi. In contrast, sexual reproduction involving insect vectors for the exchange of gametes is known from only few groups of fungi, such as Epichloë, and, thus, is likely to be of more recent origin. Therefore, we suggest that the function of chokol K as a pollinator attractive has evolved secondarily in addition to its antimicrobial properties. Similar arguments have been raised for angiosperms, where gamete transfer by animals has become common and was probably linked to the spectacular diversification of this plant group (Lunau 2004). The important role of floral volatiles for pollinator attraction in many angiosperms is thought to have evolved from the primary function of warding off herbivores and microbes from the reproductive structures of the plant (Pellmyr & Thien 1986). Our finding of a fungus derived antimicrobial compound that also attracts insects suggests that in fungi and plants the same parsimonious pathway was employed to evolve signals for the attraction of pollinators, a solution for gamete transfer in sessile, outcrossing organisms.

5. Uncited reference

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Rob Raguso (University of South Carolina) for valuable comments on the manuscript and Dr Bernhard Merz (Muséum d'histoire naturelle, Geneva) for identification of insect specimens. Financial support was provided by the SNF, the Swiss Science Fund (3100A0-101524).

Endnote

IR (Perkin–Elmer FT–IR spectrophotometer, model Spectrum ONE; film) νmax [cm−1]: 3422m, 3079w, 2964s, 2930s, 2874s, 1640m, 1452s, 1376s, 1287w, 1194m, 1152m, 1103m, 1022m, 917s, 886s, 826w, 639w, 543w, 447w. 1H-NMR (Bruker DRX-500, 500 MHz, CDCl3) δ [p.p.m.]: 5.13 (tsept. 3J=6.9, 4J=1.4 Hz, H–C (5′)); 4.78, 4.76 (2 mc, H2C (1′)); 2.39 (dt, 3J=11.3, 9.0 Hz, H–C (3)); 2.14 (br. q, 3J≈7.4 Hz, H2C (4′)); 2.01–1.91 (m, H2C (3′), H–C (4)); 1.75 (t, 3J=7.9 Hz, H2C (5)); 1.69 (d, 4J=0.9 Hz, H3C–C (6′)); 1.62 (br. s, H3C–C (6′)); 1.55 (dq, 3J=11.3, 6.8 Hz, H–C (2)); 1.43 (dq, 2J=13.0 Hz, 3J=8.1 Hz, H–C (4)); 1.28 (s, H3C–C (1)); 1.14 (br. s, HO–C (1)); 0.87 (d, 3J=6.8 Hz, H3C–C (2)). 13C-NMR (Bruker DRX-500, 125.8 MHz, CDCl3) δ [p.p.m.]: 151.59 (s, C (2′)); 131.53 (s, C (6′)); 124.36 (d, C (5′)); 108.09 (t, C (1′)); 80.30 (s, C (1)); 51.98 (d, C (3)); 47.55 (d, C (2)); 39.99 (t, C (5)); 33.77 (t, C (3′)); 28.63 (t, C (4)); 26.82 (t, C (4′)); 26.60 (q, H3C–C (1)); 25.69, 17.73 (2 q, (H3C)2C (6′)); 10.66 (q, H3C–C (2)); assignments via 1H,13C-correlation spectra. EI-MS (electron impact ionization, MAT 95 spectrometer at 70 eV) m/z (%): 222 (5, M+·), 207 (4, [M−CH3]+), 204 (13, [M−H2O]+·), 189 (7), 179 (7), 164 (12), 161 (52), 149 (6), 135 (25), 121 (28), 109 (48), 108 (17), 107 (16), 95 (25), 93 (17), 91 (10), 82 (10), 81 (12), 79 (14), 71 (12), 69 (100), 67 (20), 55 (15), 43 (30), 41 (45).

Present address: Givaudan Schweiz AG, Ueberlandstrasse 138, 8600 Dübendorf, Switzerland.

Supplementary Material

The fungus Epichloë is interacting with Botanophila flies that transfer gametes for fertilization. One compound, chokol K, was found to attract flies to the fungal stromata of Epichloë. Here we describe the synthesis of Chokol K that was used in bioassays to investigate the attractiveness of the compound to the flies

References

- Breen J.P. Acremonium endophyte interactions with enhanced plant resistance to insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1994;39:401–423. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.39.010194.002153 [Google Scholar]

- Brem D, Leuchtmann A. Epichloë grass endophytes increase herbivore resistance in the woodland grass Brachypodium sylvaticum. Oecologia. 2001;126:522–530. doi: 10.1007/s004420000551. doi:10.1007/s004420000551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultman T.L, White J.F, Bowdish T.I, Welch A.M. A new kind of mutualism between fungi and insects. Mycol. Res. 1998;102:235–238. doi:10.1017/S0953756297004802 [Google Scholar]

- Bultman T.L, Welch A.M, Boning R.A, Bowdish T.I. The cost of mutualism in a fly–fungus interaction. Oecologia. 2000;124:85–90. doi: 10.1007/s004420050027. doi:10.1007/s004420050027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connick W.J, French R.C. Volatiles emitted during the sexual stage of the Canada thistle rust fungus and by thistle flowers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991;39:185–188. doi:10.1021/jf00001a037 [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a Penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzae. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1929;10:226–236. [Google Scholar]

- Huber F, Kaiser R, Sautter W, Schiestl F.P. Floral scent emission and pollinator attraction in two species of Gymnadenia (orchidaceae) Oecologia. 2005;142:564–575. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1750-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshino, H. T., Yoshihara, T., Togiya, S., Terada, S., Tsukada, S., Okuno, M., Noguchi, A., Sakamura, S. & Ichihara, A. 1989 Antifungal compounds from stromata of Epichloë typhina on Phleum pratense In Proc. 31 Symp. Chemistry of Natural Products, Sapporo, Japan, pp. 244–251.

- Leuchtmann A. Phylogeny of Botanophila (Diptera) from Epichloë fungal host species. In: Kozlowsi J, editor. Tenth congress European society for evolutionary biology, abstract book, Krakow, Poland. ESEB; Krakow, Poland: 2005. p. 363. [Google Scholar]

- Lunau K. Adaptive radiation and coevolution–pollination biology case studies. Organ. Div. Evol. 2004;4:207–224. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2004.02.002 [Google Scholar]

- Naef A, Roy B.A, Kaiser R, Honegger R. Pollinator-mediated reproduction of systemic rust infections of Berberis vulgaris (Berberidaceae) New Phytol. 2002;154:717–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00406.x. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellmyr O, Thien L.B. Insect reproduction and floral fragrances: keys to the evolution of the angiosperms? Taxon. 1986;35:76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Raguso R.A. Floral scent, olfaction, and scent-driven foraging behavior. In: Chittka L, Thomson J.D, editors. Cognitive ecology of pollination. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. pp. 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Raguso R.A, Roy B.A. ‘Floral’ scent production by Puccinia rust fungi that mimic flowers. Mol. Ecol. 1998;7:1127–1136. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00426.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy B.A. Floral mimicry by a plant pathogen. Nature. 1993;362:56–58. doi:10.1038/362056a0 [Google Scholar]

- Roy B.A, Raguso R.A. Olfactory versus visual cues in a floral mimicry system. Oecologia. 1997;109:414–426. doi: 10.1007/s004420050101. doi:10.1007/s004420050101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardl C.L, Leuchtmann A, Spiering M.J. Symbiosis of grasses with seedborne fungal endophytes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:315–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141735. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimanuki T. Studies on the mechanisms of the infection of timothy with purple spot disease caused by Cladosporium phlei (Gregory) de Vries. Res. Bull. Hokkaido Natl Agric. Exp. Station. 1987;148:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson M, Ezra D, Hess W.M, Sears J, Strobel G. An endophytic Gliocladium sp. of Eucryphia cordifolia producing selective volatile antimicrobial compounds. Plant Sci. 2003;165:913–922. doi:10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00299-1 [Google Scholar]

- Strobel G.A, Dirkse E, Sears J, Markworth C. Volatile antimicrobials from Muscodor albus, a novel endophytic fungus. Microbiology. 2001;147:2943–2950. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-11-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimori S, Ueda T, Nakayama M. Efficient chemical conversion of (±)-chokol G to (±)-chokol A, B, C, F, and K, chokolic acid B, and chokolal A. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1994;58:1174–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Trost B.M, Phan L.T. The effect of tether substituents on the selectivity of Pd catalyzed enyne cyclizations—a total synthesis of chokol C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:4735–4738. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)74075-5 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The fungus Epichloë is interacting with Botanophila flies that transfer gametes for fertilization. One compound, chokol K, was found to attract flies to the fungal stromata of Epichloë. Here we describe the synthesis of Chokol K that was used in bioassays to investigate the attractiveness of the compound to the flies