Abstract

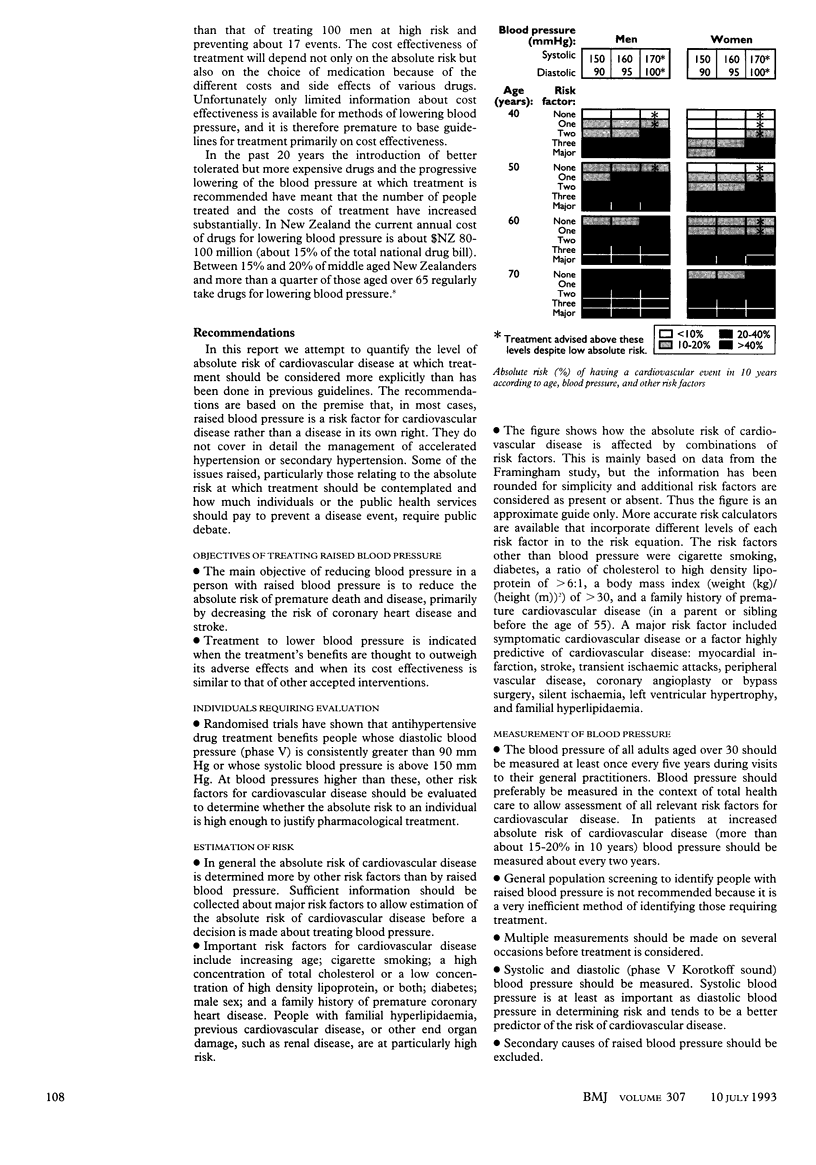

A report to the National Advisory Committee on Core Health and Disability Support Services, New Zealand, on the management of raised blood pressure recommends that decisions to treat raised blood pressure should be based primarily on the estimated absolute risk of cardiovascular disease rather than on blood pressure alone. In general, patients with a blood pressure of 150-170 mm Hg systolic or 90-100 mm Hg diastolic, or both, should be given treatment to lower blood pressure if the risk of a major cardiovascular disease event in 10 years is more than about 20%. The results of clinical trials indicate that, at this level of absolute risk, 150 people would require treatment to reduce the annual number of cardiovascular events by about one. Implementation of these recommendations may result in a smaller proportion of people aged under 60, particularly women, receiving treatment but an increased proportion of older people treated. In the absence of specific contraindications, low dose diuretics and low dose beta blockers should be considered for first line treatment, since for only these drug groups is there direct evidence of reduced risk of stroke and coronary disease in people with raised blood pressure.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson K. M., Wilson P. W., Odell P. M., Kannel W. B. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation. 1991 Jan;83(1):356–362. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen J. E., Køber L., Torp-Pedersen C., Johansen P. Relation between dose of bendrofluazide, antihypertensive effect, and adverse biochemical effects. BMJ. 1990 Apr 14;300(6730):975–978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6730.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R., Peto R., MacMahon S., Hebert P., Fiebach N. H., Eberlein K. A., Godwin J., Qizilbash N., Taylor J. O., Hennekens C. H. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990 Apr 7;335(8693):827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank J. M., Thorp J. M., Zacharias F. J. Benefits and potential harm of lowering high blood pressure. Lancet. 1987 Mar 14;1(8533):581–584. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Wilson N. The evolution of antihypertensive therapy. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(11):1239–1243. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90130-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMahon S., Peto R., Cutler J., Collins R., Sorlie P., Neaton J., Abbott R., Godwin J., Dyer A., Stamler J. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990 Mar 31;335(8692):765–774. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer M. A., Braunwald E., Moyé L. A., Basta L., Brown E. J., Jr, Cuddy T. E., Davis B. R., Geltman E. M., Goldman S., Flaker G. C. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992 Sep 3;327(10):669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]