Abstract

Although the β-rich self-assemblies are a major structural class for polypeptides and the focus of intense research, little is known about their atomic structures and dynamics due to their insoluble and noncrystalline nature. We developed a protein engineering strategy that captures a self-assembly segment in a water-soluble molecule. A predefined number of self-assembling peptide units are linked, and the β-sheet ends are capped to prevent aggregation, which yields a mono-dispersed soluble protein. We tested this strategy by using Borrelia outer surface protein (OspA) whose single-layer β-sheet located between two globular domains consists of two β-hairpin units and thus can be considered as a prototype of self-assembly. We constructed self-assembly mimics of different sizes and determined their atomic structures using x-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. Highly regular β-sheet geometries were maintained in these structures, and peptide units had a nearly identical conformation, supporting the concept that a peptide in the regular β-geometry is primed for self-assembly. However, we found small but significant differences in the relative orientation between adjacent peptide units in terms of β-sheet twist and bend, suggesting their inherent flexibility. Modeling shows how this conformational diversity, when propagated over a large number of peptide units, can lead to a substantial degree of nanoscale polymorphism of self-assemblies.

Keywords: β-sheet, β-strand interaction, amyloid fibril, nanomaterial, protein engineering

In the recent years, it has become clear that polypeptides have a general property to self-assemble into a β-rich structure, such as fibrils, films, and ribbons, as evidenced by the fact that many natural and designed peptides form self-assemblies (1, 2). Water-soluble proteins have evolved to avoid self-assembly by employing negative design strategies (3). Despite their importance as a major structural class of polypeptides and as promising building blocks for nanomaterials (4), little is known about atomic structures of peptide self-assemblies. It is generally considered that, in these β-rich self-assemblies, a peptide unit (or a portion thereof) takes on a β-strand conformation and intermolecular interactions between β-strand building blocks lead to the formation of a continuous β-sheet in which the β-strands run perpendicular to the long axis of the assembly and that the presence and absence of higher-order assembly, such as the lamination of multiple β-sheets, determine the final macroscopic features (5).

The very nature of a peptide to self-assemble creates obstacles toward high-resolution structure determination of peptide self-assemblies. First, the self-assemblies are usually water-insoluble and noncrystalline, which makes it extremely difficult to apply the standard structure determination techniques available for water-soluble proteins, i.e., x-ray crystallography and high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. Second, the slow nucleation and rapid propagation steps characteristic of self-assembly reactions almost always result in a sample containing an ensemble of assemblies with different size and possibly different conformation. It is difficult to deduce high-resolution structures from data collected over such a polydispersed sample.

The conformations of the peptide units in fibrils have been determined by using solid-state NMR spectroscopy, and modes of higher-order assemblies of fibril-forming peptides have been deduced (6–9). Because solid-state NMR measurements provide conformational restraints that mostly define short distances and torsional angles, it is difficult to determine higher-order structures of self-assemblies such as twisting and bending. Recently, the crystal structures for peptides that form fibrils have been determined (10, 11), which revealed the “cross-β spine” structure (10). It is important to note that these methods either assume or require that all copies of a peptide unit take on an identical conformation throughout a sample. Also, crystallization requires three-dimensional packing of peptides with essentially infinite lamination of β-sheet layers, which in turn requires each β-sheet to be perfectly flat. These features are different from those of actual peptide self-assemblies. Recent molecular dynamics analyses suggest that the cross-β spine structures found in the sup35 peptide crystals represent a high-energy state and exhibit a significant twist as their structures are relaxed in computation (12).

There is still a large gap in our knowledge of peptide self-assemblies between the β-rich structure of the peptide unit and macroscopic morphology of self-assemblies. Major questions include (i) how peptides are assembled in these structures that allow for the formation of continuous β-sheets but prevent continuous lamination, (ii) how much conformational variations individual units have within self-assembly, and (iii) how the nanoscale polymorphism of assemblies is generated. High-resolution structures of larger segments of peptide self-assemblies, larger than single units, are required to address these issues.

In this study, we developed a protein-engineering approach that overcomes the fundamental difficulties in the structure determination of peptide self-assembly. We eliminate the sample heterogeneity problem by covalently linking a defined number of a peptide unit (Fig. 1A). We prevent further lateral assembly of the linked units by sealing the edges of the assembly with “anti-aggregation caps.” Furthermore, these caps prevent lamination of the assembly. We term these “linked and capped” self-assemblies as peptide self-assembly mimics (PSAMs). Most importantly, the PSAMs are monomeric and water-soluble, allowing us to apply x-ray crystallography and solution NMR spectroscopy.

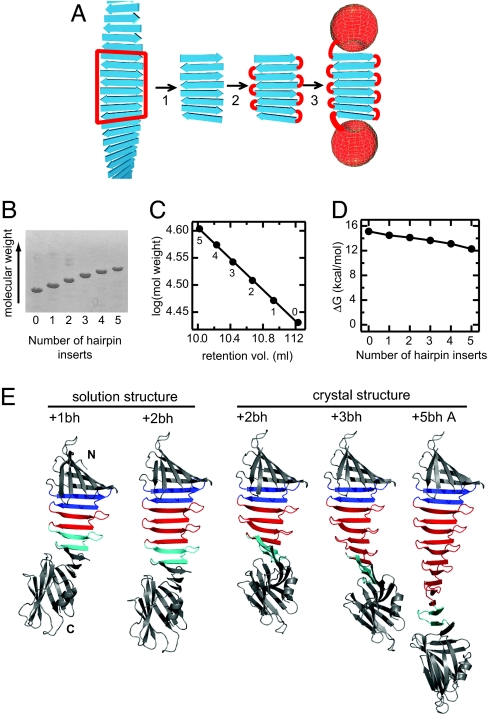

Fig. 1.

Design principle, construction, and structures of peptide self-assembly mimics. (A) Scheme showing the concept of our “link-and-cap” strategy. A segment of peptide self-assembly is excised (step 1), covalently linked (step 2), and capped (step 3). (B–D) Construction of OspA-based PSAMs. (B) SDS/PAGE of purified PSAMs containing different numbers of additional hairpin units. (C) Correlation between the retention volume on a Superdex 75 column (Amersham; horizontal axis) and the expected size of the proteins. The data points are labeled with the numbers of hairpin inserts. (D) The free energy difference for the overall conformational stability as determined by chemical denaturation plotted as a function of the number of hairpin inserts. Stability measurements were performed as described in Yan et al. (28). (E) Cartoon drawings of the atomic structures of PSAMs determined in this work. The N and C termini are designated in the OspA+1bh structure (far left). The β-hairpins in cyan are the original β-hairpin unit (strands 9 and 10 in wild-type OspA), those in red are additional copies, and those in blue are the homologous β-hairpin (strands 7 and 8). The N- and C-terminal globular domains are shown in gray.

We demonstrate our “link-and-cap” strategy using a 23-residue fibril-forming peptide designed from the “single-layer” β-sheet (SLB) of Borrelia outer surface protein A (OspA) (13). The SLB, located in the center of the molecule (Fig. 1E), is very flat with highly regular backbone geometry and consists of two homologous β-hairpins (14). The fibril-forming peptide was designed from the second β-hairpin. Thus, this peptide represents a unique model system for peptide assembly in which the atomic structure of the peptide building block is known in the state that appear capable of self-assembly. The SLB structure was also used as a template for computational design of fibril-forming peptides (15). We have directly demonstrated the similarity between the SLB and self-assembly by successfully propagating the β-sheet by the addition of copies of the β-hairpin peptide unit, thus establishing model PSAMs (16).

In this work, we successfully engineered OspA-based PSAMs of different sizes up to the one containing five additional β-hairpin units (i.e., 10 additional β-strands). These PSAMs are stable, and we successfully determined their atomic structures using x-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. These structures explain how small differences in the building block conformation lead to nanoscale polymorphism of β-rich self-assemblies. These PSAMs also offer important templates for engineering of nonglobular proteins.

Results and Discussion

Design and Construction of PSAMs.

We engineered a series of PSAMs containing self-assemblies of different sizes (Fig. 1B). We term these PSAMs as OspA+nbh, where n denotes the number of β-hairpin copies added to the self-assembly segment (e.g., OspA+5bh contains five additional β-hairpin copies). For brevity, we refer to a β-sheet consisting of copies of the β-hairpin unit as “β-repeat.” The β-repeats of increasing length mimic propagation of peptide self-assembly, with the exception that the β-hairpin units are covalently linked in a β-repeat. All of these PSAMs were highly water-soluble, monomeric, and stable (Fig. 1 C and D). These results demonstrate that large monolayer β-repeats can be stably formed in the context of OspA where both of the β-sheet edges are capped.

X-Ray Crystal Structures of PSAMs.

We determined the crystal structures of OspA+2bh at 2.5-Å resolution, +3bh at 2.4 Å resolution, and+5bh at 3.1 Å resolution (Table 1). We improved the resolution of OspA+3bh to 1.6 Å by using a set of surface mutations that enhance OspA crystallization (termed OspA+3bh-sm1) (17). Although the original and surface mutant proteins crystallized in different space groups (Table 1), their structures are very similar (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), suggesting little effect of the surface mutations on the structure of this PSAM. The crystals of OspA+2bh and OspA+3bh contained one molecule in the asymmetric unit, whereas OspA+5bh contained three. Together we have five independent structures of PSAMs comprised of the identical β-hairpin peptide unit. In all structures, the two globular domains, or the caps, maintained their respective wild-type conformations. The β-repeat segments of these variants all folded into the canonical anti-parallel β-sheet with a highly regular geometry (Figs. 1E and 2). The diffraction images of the OspA+5bh crystal exhibited intense diffraction maxima corresponding to a ≈4.6 Å spacing, a hallmark of β-rich self-assembly (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), indicating structural similarity between the PSAMs and β-rich peptide self-assemblies.

Table 1.

Statistics for the crystal structures of OspA+2bh, OspA+3bh, and OspA+5bh

| Protein (PDB ID) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OspA+2bh (2AF5) | OspA+3bh (2FKG) | OspA+3bh-sm1 (2HKD) | OspA+5bh (2FKJ) | |

| Data collection statistics | ||||

| Space group | P21 | C2 | P212121 | P21 |

| Cell parameters | a = 48.55 | a = 99.45 | a = 37.19 | a = 72.15 |

| b = 55.33 | b = 76.89 | b = 76.46 | b = 105.50 | |

| c = 70.36 | c = 51.94 | c = 120.91 | c = 88.98 | |

| β=104.0 | β=120.0 | — | β=93.24 | |

| Beamline | APS 14-ID | APS 17-ID | APS 22-ID | APS 17-ID |

| Wavelength, A | 0.9795 | 1.0000 | 0.9718 | 1.0000 |

| Resolution,* Å | 30–2.5 (2.56–2.50) | 50–2.4 (2.49–2.4) | 50–1.6 (1.66–1.60) | 50–3.1 (3.21–3.1) |

| Completeness, % | 97.7 (99.9) | 99.6 (100) | 96.6 (93.3) | 98.9 (100) |

| I/σ(I) | 16.53 (2.45) | 23.12 (3.26) | 17.74 (2.12) | 28.83 (10.19) |

| Rmerge† | 0.081 (0.318) | 0.046 (0.324) | 0.157 (0.710) | 0.061 (0.114) |

| Average redundancy | 5.4 (5.5) | 3.1 (3.1) | 5.4 (4.6) | 4.9 (5.0) |

| Refinement statistics | ||||

| Resolution range, Å | 20.0–2.5 | 20.0–2.4 | 20.0–1.6 | 20.0–3.1 |

| Reflections used (free) | 11,367 (1,287) | 12,593 (661) | 42,184 (2,223) | 22,668 (1,161) |

| R factor‡ | 0.244 | 0.219 | 0.196 | 0.247 |

| Rfree§ | 0.275 | 0.255 | 0.237 | 0.282 |

| rms deviations | ||||

| Bonds, Å | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.007 |

| Angles, ° | 1.480 | 1.499 | 1.444 | 1.102 |

| No. protein residues | 292 | 315 | 315 | 361 |

| No. waters | 52 | 70 | 424 | 0 |

| Average B factor, Å2 | 20.50 | 58.78 | 18.68 | 79.51 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics | ||||

| Most favored, % | 89.1 | 85.5 | 91.0 | 84.4 |

| Additionally allowed, % | 10.2 | 12.1 | 8.7 | 14.5 |

| Generally allowed, % | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

*Highest resolution shell is shown in parentheses.

†Rmerge = ΣΣ| I(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/ΣΣ〈I(hkl)i〉 over iobservations of a reflection hkl.

‡R factor = Σ ||F(obs)| − |F(calc)||/Σ|F(obs)|.

§Rfree is R with 5% (10% for 2AF5) of reflections sequestered before refinement.

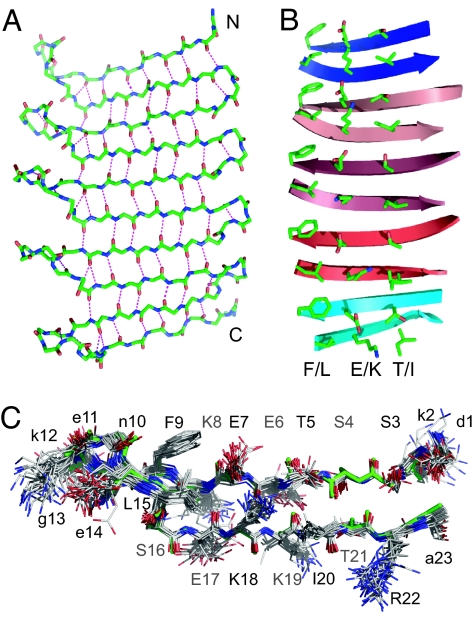

Fig. 2.

Structures of β-repeat segments in PSAMs. (A) The backbone structure of the β-repeat segment in the crystal structure of OspA+3bh-sm1. The hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms are shown as dashed lines. (B) Side chain conformations of the β-repeat segment of OspA+3bh. Only the residues on the front face of the β-sheet are shown. The β-sheet backbone is shown as arrows. For clarity, the turn regions are omitted. The three cross-strand amino acid ladders are labeled with their respective amino acid compositions (“F/L,” “E/K,” and “T/I”). These ladders extend short and/or imperfect ones present in wild-type OspA (“FLFV,” “EKEK,” and “TVTI,” respectively) (14). (C) Superposition of a total of 26 copies of the β-hairpin unit from the PSAM crystal structures. The backbone of the original β-hairpin unit from wild-type OspA is shown in green. Amino acid resides in the β-strand regions are labeled with an uppercase letter and residue number. Strand residues labeled in black have their side chain pointing toward the reader, and those labeled in gray have their side chain pointing away from the reader. Residues in the turn regions are labeled with a lowercase letter.

β-Hairpin Units Maintain the Conformation.

The series of PSAM structures yielded a total of 26 crystallographically independent structures of the β-hairpin peptide unit [the original unit from the wild type; three (original plus two copies) from OspA+2bh; four from OspA+3bh; and six each from the three OspA+5bh molecules]. Their backbone conformations are very similar (Fig. 2) with pair-wise rmsd values of 0.3–0.4 Å for the Cα atoms in the β-strand segments. The backbone dihedral angles also illustrate their similarities (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This conformational similarity further strengthens the notion that a peptide in the regular β-geometry is primed for self-assembly and that β-sheets in natural globular proteins avoid self-assembly using negative design strategies.

High-Resolution Structure Reveals Heterogeneity of Side Chain Conformation.

The 1.6-Å resolution structure of OspA+3bh-sm1 allows us to examine side chain conformations in a peptide self-assembly segment. Equivalent side chains form “cross-strand ladders” along the long axis of the assembly (Fig. 2B). Such cross-strand ladders are a central feature of actual β-rich self-assemblies (8–11). Although the residues in the “F/L” ladder have similar rotamers throughout the β-repeat, the side chain conformations in the E/K and T/I ladders vary significantly, suggesting considerable conformational heterogeneity on the assembly surface. Although the β-repeats in the PSAMs engineered in this work are monolayer, they can be viewed as an intermediate state for multilayer assemblies. Because the “cross-β spine” core of multilayer self-assemblies is expected to be tightly packed and highly ordered (10), conformational heterogeneity of side chains should present a significant energy barrier for the formation of laminated self-assembly.

Conformational Flexibility of PSAMs.

We also performed NMR experiments to characterize the solution structures and conformational dynamics of OspA+1bh and OspA+2bh. Residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) of the backbone1H-15N pairs and the effective transverse relaxation rates (R2) for 15N were determined (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The RDC data are sufficient for determining the relative orientation between the N- and C-terminal globular domains (18), which depends on the conformation of the β-repeat that links the two globular domains and thus it in turn serves as a sensitive measure for the β-repeat conformation. OspA+1bh was found to be rigid and the overall conformation of OspA+1bh was very similar to a model in which the added β-hairpin is assumed to be in the same conformation as the original (Fig. 1E and Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In contrast, the N-terminal globular domain of OspA+2bh shows signs of increased mobility (Figs. 8 and 9) and its solution structure was flatter than its crystal structure, although the crystal structure falls within the range of conformations expected from the NMR data (Figs. 1E, 8, and 9). These results suggest inherent flexibility of larger β-repeats.

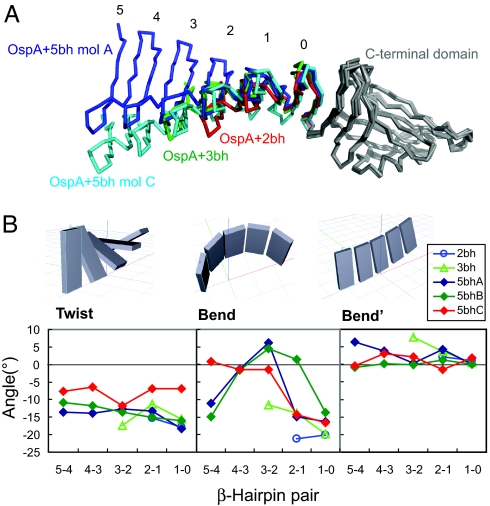

The superposition of OspA+nbh crystal structures (Fig. 3A) strengthens the notion of inherent plasticity of the β-repeat segments. Although the individual β-hairpin units have the identical amino acid sequence and very similar conformations (Fig. 2C), the overall conformations of β-repeats as a whole show a significant degree of variation. Particularly interesting are comparisons of an identical molecule in different environments. In addition to the crystal and NMR structures of OspA+2bh as described above, the three molecules in the asymmetric unit of OspA+5bh give such an opportunity. The conformations of molecules A and B in the OspA+5bh crystal structure were very similar but different from that of molecule C in the same crystal (Fig. 3A). Thus, the β-repeats maintain short-range conformational homogeneity among the individual β-hairpin units but exhibit long-range heterogeneity as the units are assembled.

Fig. 3.

Structural differences of β-repeats. (A) Comparison of the PSAM structures. The structures are superimposed using the C-terminal globular domain. The N-terminal globular domain is omitted for clarity. The β-hairpin units in the PSAMs are labeled from the C terminus of the β-repeat segment to the N terminus starting from zero for the original β-hairpin unit. This “backward” direction is because a new copy of the β-hairpin unit is added N-terminal to the existing units. (B) The degrees of twist and bend between β-hairpin pairs in the PSAM crystal structures. β-hairpin pairs are denoted with the names of the two β-hairpin units connected with a hyphen. The definitions of twist, bend, and bend′ are provided in Materials and Methods.

Quantitative Analysis of β-Repeat Conformation.

We then systematically compared the relative orientation between two adjacent β-hairpin units in the two-hairpin (i.e., four-strand) sections from all of the crystal structures. This analysis identified that the differences among the PSAM structures were chiefly due to different degrees of β-sheet bending (Fig. 3B). The β-repeats showed large variations in bending even within a single PSAM, suggesting that the β-repeats have considerable flexibility in this direction and that the observed variations are a result of statistical sampling of a broad range of low energy conformations. In contrast, most of the β-repeats exhibited similar values of left-handed twist with an exception of molecule “C” of OspA+5bh. This observation suggests that these β-repeats have a preferred twist that may well be dependent on the amino acid sequence of the β-hairpin unit. Indeed, our recent results suggest that sequence motifs in the cross-strand ladders affect sheet twist (K.M., G.G., S.Y., A.K., and S.K., unpublished data). Furthermore, the degrees of twist do not significantly fluctuate within one molecule (i.e., ≈15° per β-hairpin for most PSAMs, and ≈8° for OspA+5bh molecule C except for one hairpin pair; Fig. 3), suggesting that these β-repeats as a whole behave like an elastic sheet in which structural strain in sheet twist is dissipated over the entire length of a β-repeat. The average value of twist (≈15° per β-hairpin, or ≈7.5° per strand) is similar to that found for some fibrils (e.g., 7° per strand for Gln10; ref. 19), suggesting similarity between the β-repeat structures in the PSAMs and those in fibrils.

Larger Self-Assemblies Modeled from the PSAM Structures.

The x-ray structures of β-repeat segments define the relative orientation between adjacent β-hairpin units, and thus they allowed us to model larger β-ribbon superstructures of peptide self-assembly segment at an atomic level. From the above analysis, we chose five β-hairpin pairs (i.e., sections containing four β-strands) that are representative in terms of sheet bend or twist (Figs. 3A and 4). Each of these four-strand sections defines the relative orientation between adjacent two-strand (i.e., β-hairpin) building blocks and thus serves as a template for recursive modeling of a self-assembly where a new building block is added to the existing segment by reproducing the bend and twist of the template. From each template, we first modeled the smallest assembly segments consisting of three β-hairpins (Fig. 4). We found that steric clashes in these initial models were readily eliminated by simple energy minimization and that all of these triplet structures had similar internal energies (data not shown). These results indicate that none of these templates have steric problems as a building block in recursive modeling of larger self-assembly.

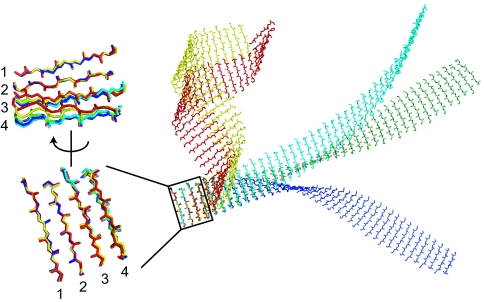

Fig. 4.

Demonstration of the propagation of small conformational differences of β-hairpin pairs (i.e., four-stranded building blocks) leading to substantial β-ribbon polymorphism. Larger peptide self-assemblies were modeled using six representative β-hairpin pairs. Different building blocks are shown in different colors (cyan, 5bh molecule C, β-hairpin units 4 and 3; blue, 5bh molecule A, units 3 and2; yellow, 5bh molecule A, units 5 and 4; green, 5bh molecule C, units 3 and 2; red, 2bh units 2 and 1), and only the backbone traces of the β-strand regions are shown for clarity. These β-hairpin pairs were superimposed using the first two β-strands (labeled with “1” and “2,” respectively). Different relative orientations of the third and fourth β-strands, with respect to the first and second, are evident. β-Ribbon superstructures shown at Right were constructed in a step-wise manner. Starting from a four-stranded building block, a copy of the building block was generated. The third and fourth β-strands of the original block and the first and second β-strands of the copy (which have the identical sequence and nearly identical conformation; Fig. 2C) were then superimposed. In this way, the third and fourth β-strands of the copy are now placed as the fifth and sixth β-strands of the original building block, and the relative orientation between adjacent two-stranded units (i.e., β-strands 1–2 and 3–4, and β-strands 3–4 and β-strand 5–6) is kept identical. These steps were iterated until a superstructure of sufficient length was generated.

We then generated longer self-assembly models by repeating the stepwise propagation of the β-hairpin (two-strand) unit (Fig. 4). The resulting models (termed β-ribbons) define a substantial range of nanoscale morphology of self-assemblies, from nearly flat to highly curled, as the result of amplification of small conformational differences in the underlying β-repeat unit over many copies. It is important to note that these discrete β-ribbon conformations should be taken as models that define the range of possible morphology rather than those that accurately represent actual structures, because of the inherent flexibility in inter-hairpin conformations. Significant bending of β-sheet result in a curled β-ribbon as predicted with a simplified model (20, 21). All of the β-ribbon superstructures have left-handed twist, due to the left-handed twist of the underlying β-repeats.

The nearly flat β-ribbon model (shown in green in Fig. 4) is very similar to the β-sheet layer in the common models of fibrils. Multiple copies of a flat ribbon could form a laminated fibril with small structural adjustment. In contrast, a single type of highly curled β-ribbons cannot form higher-order, laminated self-assemblies. The bending in these curly β-ribbons also causes the β-strands to align in a different orientation from the standard “cross-β” orientation where β-strands are perpendicular to the long axis of the assembly. Although such highly curled β-ribbons without β-sheet lamination are probably unstable, a single-layer β-ribbon may exist as a metastable intermediate (22–24). Indeed, highly curled structures similar to the β-ribbons constructed here have been observed as intermediate species in peptide self-assembly, although the authors modeled them to be two-layered β-sheets (25). It is quite possible that a monolayer β-ribbon forms, at least transiently, via strong lateral interactions within a β-sheet mediated by the backbone hydrogen bonding and tight side chain packing, resulting in a highly curled helical superstructure. Because of inherent flexibility of monolayer β-ribbons as revealed here, such curly intermediates can be later converted to a straighter and flatter form concomitantly with β-sheet lamination to form higher-order assembly. Clearly, this hypothesis would apply to a subset of β-rich self-assemblies in which a peptide unit is contained within a single β-sheet layer but not to those in which a peptide unit spans two β-sheet layers such as Aβ fibrils (8, 9).

Conclusions

The series of atomic structures corresponding to peptide self-assembly segments determined in this work significantly expands our knowledge of this important class of protein structure. The atomic structures of self-assembly segments containing multiple units enable us to determine variations in the relative orientations between adjacent units (i.e., twist and bend). These structures provide critical linkage between the peptide unit conformation and the nanoscale morphology of self-assembly, and they serve as important structural templates for modeling higher-order structures of self-assemblies. Our “link-and-cap” strategy has been highly effective in overcoming fundamental difficulties in structural studies of peptide self-assembly. The covalent linkage between peptide units greatly enhances the stability of a self-assembly compared with that made of unlinked peptide units, and thus we envision that we can determine atomic structures of PSAMs constructed from diverse peptide sequences. It is tempting to speculate that an extension of this strategy may yield relevant molecular structures of higher-order peptide self-assemblies including cross-β fibrils. Furthermore, PSAMs are themselves repeat proteins (26) and they represent a new class of nanomaterials. The ability to determine the atomic structure and thermodynamic properties makes the PSAMs a unique system for designing nonglobular, filamentous proteins.

Materials and Methods

Protein Production.

The PSAMs were designed by inserting copies of the β-hairpin segment (DKSSTEEKFNEKGELSEKKITRA; Fig. 2C) between residues K117 and D118 of OspA. The expression vectors for OspA+1bh and OspA+2bh were described (16), and those for OspA+3bh, OspA+4bh, and OspA+5bh were constructed in the same manner. 15N-enriched samples were prepared as described (27). Additionally, the β-repeat segment of OspA+3bh was subcloned into the corresponding region of the OspA-sm1 expression vector using the SpeI and PstI restriction sites, resulting in OspA+3bh-sm1. OspA-sm1 is a surface-engineered mutant of OspA that crystallize efficiently (17). All of the proteins were expressed as a histag-fusion protein in E. coli and purified as described (28).

Crystallization and X-Ray Crystal Structure Determination.

Initial crystallization screen was performed as described (17). Crystallization conditions were optimized by using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. The crystallization drops contained equal volumes (2 μl each) of reservoir solution and protein sample (≈6–66 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8). Crystallization conditions were as follows: 25% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 1000, 100 mM MnSO4, and 100 mM Mes (pH 6.0) for OspA+2bh; 30% PEG 1000, 2% PEG 400, 100 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), and 200 mM NaCl for OspA+3bh; 31% PEG 400, 2% MPD, 100 mM Tris·HCl (pH 9.0) for OspA+3bh-sm1; 24% PEG 1000, 100 mM acetic acid (pH 5.3), and 200 mM LiSO4 for OspA+5bh.

The x-ray diffraction data were collected at the 14-ID, 17-ID, and 22-ID Sectors (Advanced Photon Source at the Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL). Crystal data and data collection statistics are summarized in Table 1. X-ray diffraction data were processed with HKL2000 (29). The OspA+nbh structures were determined by molecular replacement with the program MOLREP in CCP4 (30). The N- and C-terminal globular domains (residues 23–131 and 132–273, respectively) of the wild-type OspA structure (Protein Data Bank ID 1OSP) were used as the search models. The rigid body refinement was carried out with CNS1.1 (26). The SigmaA-weighted 2Fobs − Fcalc and Fobs − Fcalc Fourier maps were calculated and examined. The engineered β-hairpins were built at this stage. The model building was carried out by using the Coot program (31). The simulated annealing and the search for water molecules were performed in CNS1.1. The TLS (Translation/Libration/Screw) and bulk solvent parameters, restrained temperature factor, and final positional refinement were completed with REFMAC5 (28, 29). Molecular graphics were generated by using PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

NMR Spectroscopy and Solution Structure Refinement.

Resonance assignments of wild-type OspA and OspA+1bh have been described (16, 27). Although the spectra of OspA+2bh were very close to those of OspA+1bh, which greatly facilitated resonance assignment process of the globular domains, many of the resonances for the inserted segment could not be assigned due to the presence of two identical 23-residue segments (Fig. 8). However, it should be noted that the available data for the assigned residues were sufficient for defining the global conformation and characterizing conformational dynamics.

RDC and 15N relaxation data were collected on NMR samples containing ≈1 mM 15N-labeled protein in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0 and 50 mM sodium chloride prepared in 90% H2O and 10% D2O. OspA and OspA+1bh were placed in stretched 4% acrylamide gels, and OspA+2bh was placed in 3% acrylamide gels for RDC measurements (32, 33). Two-dimensional sensitivity- and gradient-enhanced 15N TROSY spectra were acquired at 45°C on a Varian (Palo Alto, CA) INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe and used to determine the 1H–15N dipolar couplings (34). The 15N R2-dispersion profiles (35) were acquired on a Varian INOVA 500 MHz spectrometer.

All simulations were performed by using AMBER 8 (36) essentially following the method of Chou et al. (37).

Further details of NMR measurements and structure calculation are described in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Analysis of β-Repeat Conformation.

For each β-hairpin, we first defined the orthogonal reference axes as follows. We determined the orientation of the β-hairpin unit using the backbone of the first β-strand of the peptide unit (the “STEEK” segment; Fig. 2C), determined the averaged direction of the Cα–Cβ vectors of these residues (which is almost perpendicular to the β-strand vector), and then defined the third vector normal to the plane made by the first two vectors. Finally, the average Cα–Cβ vector was replaced with a vector normal to the plane made by the other two vectors.

We then calculated the rotation matrix between adjacent β-hairpin units using the Lsqkab and Pdbset program in the CCP4 suite (30). The rotation angles about the three axes (bend′, the Cα–Cβ direction; bend, β-strand direction; and twist, the axis normal to the first two directions, i.e., the long axis of the assembly) were determined by deconvoluting the rotation matrix into rotations about the three axes. The rotations were applied in the following manner

where R represents a rotation matrix, α is the angle for bend′, β is the angle for bend, and γ is the angle for twist.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Hauptman–Woodward Medical Research Institute for the initial screening of crystallization conditions, Dr. Anthony A. Kossiakoff and Serdar Uysal for helpful discussions, and Lin Silver for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-GM57215 and U54-GM074946 and by the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract W-31-109-Eng-38. Use of the IMCA-CAT Sector 17-ID was supported by the companies of the Industrial Macromolecular Crystallography Association through a contract with the Center for Advanced Radiation Sources at the University of Chicago. Use of SER-CAT Sector 22-ID was supported by institutions listed at www.ser-cat.org/members.html. Use of the BioCARS Sector 14ID was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, under Grant RR07707.

Abbreviations

- PSAM

peptide self-assembly mimic

- OspA

outer surface protein A

- RDC

residual dipolar coupling.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

Data deposition: The coordinates and structure factors reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 2AF5, 2FKG, 2HKD, and 2FKJ).

References

- 1.Dobson CM. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Serrano L. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajagopal K, Schneider JP. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunde M, Serpell LC, Bartlam M, Fraser PE, Pepys MB, Blake CC. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:729–739. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaroniec CP, MacPhee CE, Bajaj VS, McMahon MT, Dobson CM, Griffin RG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:711–716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304849101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tycko R. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lührs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Dobeli H, Schubert D, Riek R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petkova AT, Yau WM, Tycko R. Biochemistry. 2006;45:498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson R, Sawaya MR, Balbirnie M, Madsen AO, Riekel C, Grothe R, Eisenberg D. Nature. 2005;435:773–778. doi: 10.1038/nature03680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makin OS, Atkins E, Sikorski P, Johansson J, Serpell LC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:315–320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406847102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esposito L, Pedone C, Vitagliano L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11533–11538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602345103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohnishi S, Koide A, Koide S. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:477–489. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Dunn JJ, Luft BJ, Lawson CL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3584–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez De La Paz M, Goldie K, Zurdo J, Lacroix E, Dobson CM, Hoenger A, Serrano L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16052–16057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252340199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koide S, Huang X, Link K, Koide A, Bu Z, Engelman DM. Nature. 2000;403:456–460. doi: 10.1038/35000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makabe K, Tereshko V, Gawlak G, Yan S, Koide S. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1907–1914. doi: 10.1110/ps.062246706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prestegard JH. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:517–522. doi: 10.1038/756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambashivan S, Liu Y, Sawaya MR, Gingery M, Eisenberg D. Nature. 2005;437:266–269. doi: 10.1038/nature03916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggeli A, Fytas G, Vlassopoulos D, McLeish TC, Mawer PJ, Boden N. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:378–388. doi: 10.1021/bm000080z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggeli A, Nyrkova IA, Bell M, Harding R, Carrick L, McLeish TC, Semenov AN, Boden N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11857–11862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191250198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haspel N, Zanuy D, Ma B, Wolfson H, Nussinov R. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:1213–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eakin CM, Berman AJ, Miranker AD. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:202–208. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bader R, Bamford R, Zurdo J, Luisi BF, Dobson CM. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:189–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marini DM, Hwang W, Lauffenburger DA, Zhang S, Kamm RD. Nano Lett. 2002;2:295–299. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kajava AV. J Struct Biol. 2001;134:132–144. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pham T-N, Koide S. J Biomol NMR. 1998;11:407–414. doi: 10.1023/a:1008246908142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan S, Gawlak G, Smith J, Silver L, Koide A, Koide S. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:811–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collaborative Computational Project No 4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishii Y, Markus MA, Tycko R. J Biomol NMR. 2001;21:141–151. doi: 10.1023/a:1012417721455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou JJ, Gaemers S, Howder B, Louis JM, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 2001;21:377–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1013336502594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weigelt J. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10778–10779. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tollinger M, Skrynnikov NR, Mulder FA, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11341–11352. doi: 10.1021/ja011300z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Case DA, Cheatham TE III, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Jr, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou JJ, Li S, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 2000;18:217–227. doi: 10.1023/a:1026563923774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.