Abstract

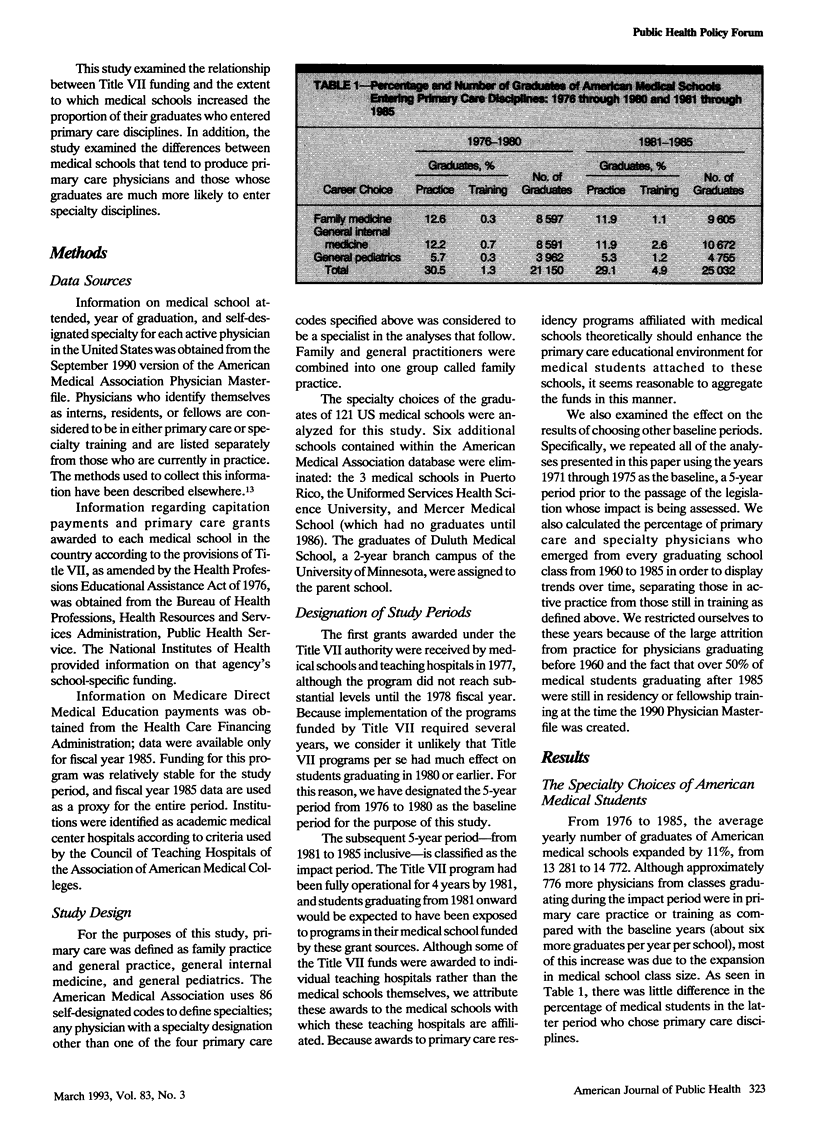

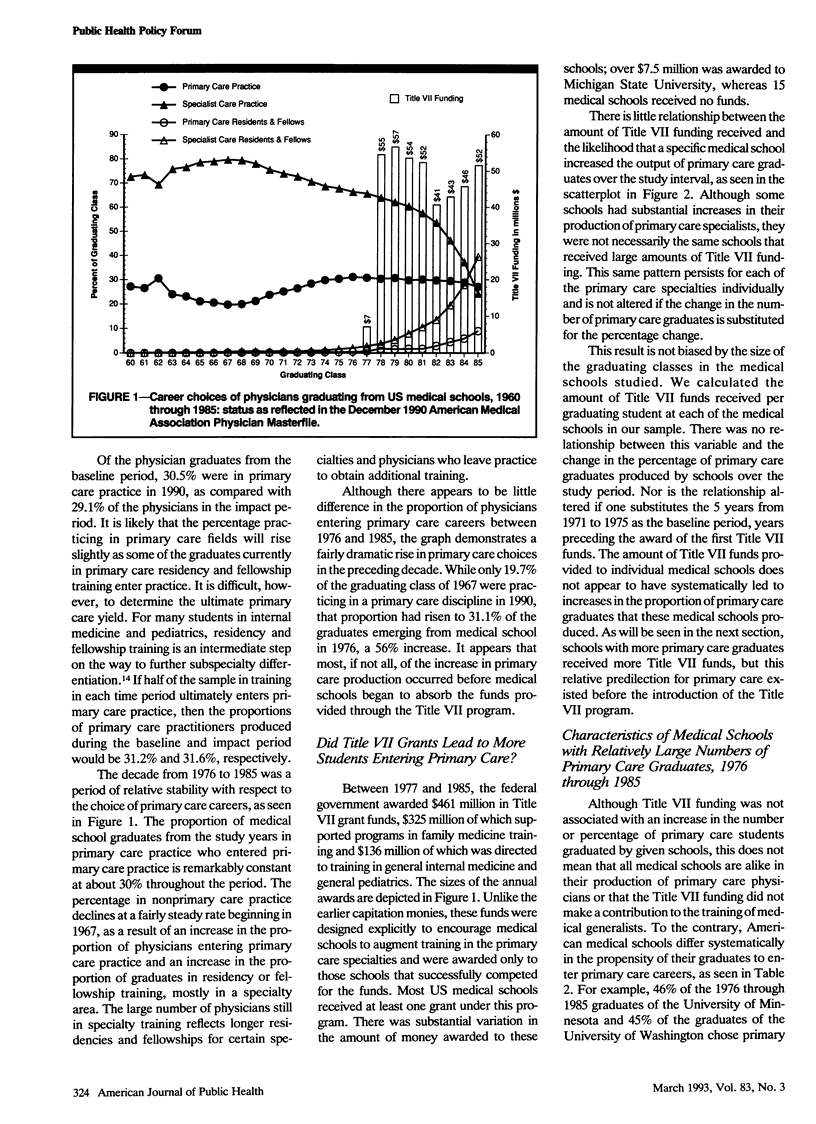

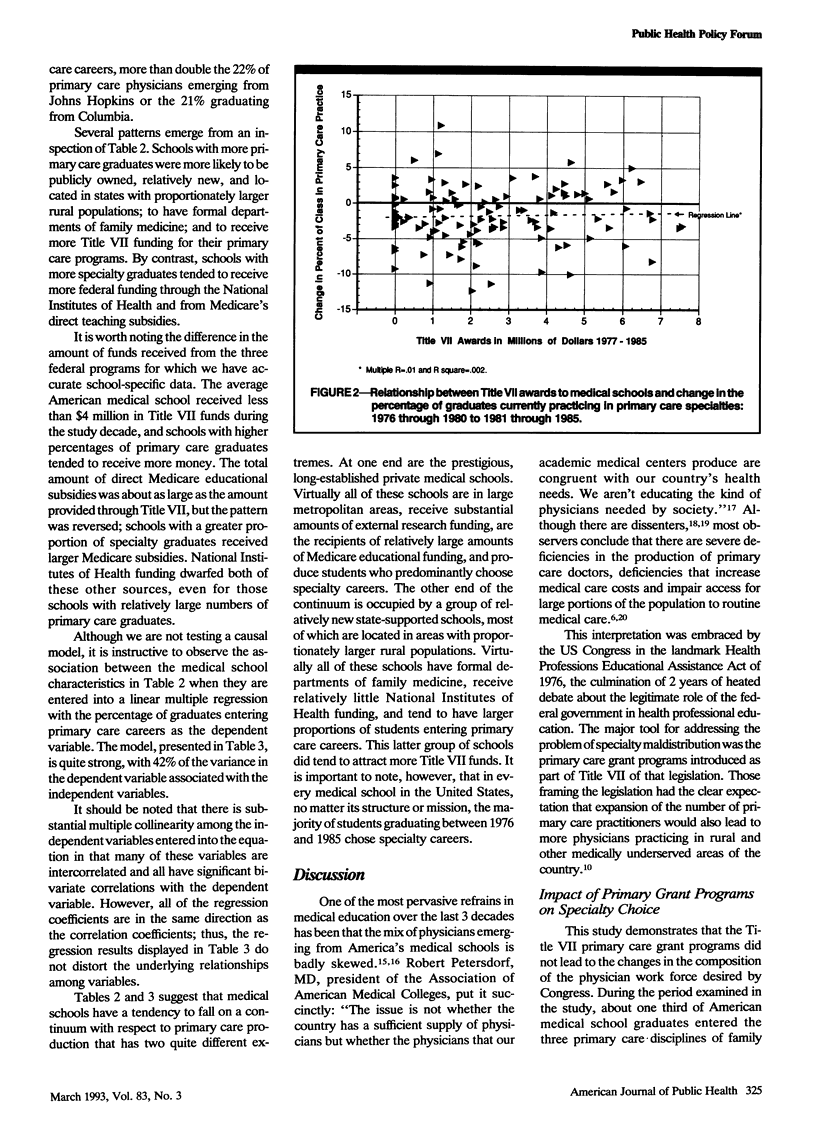

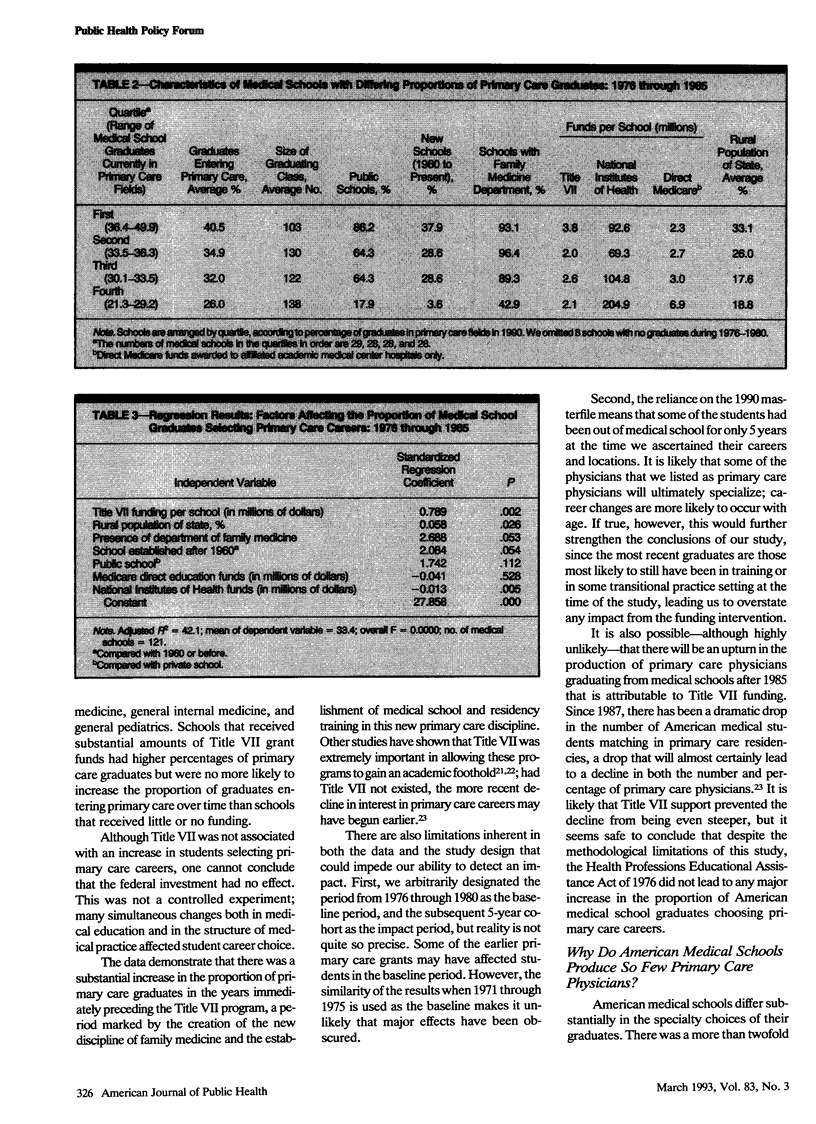

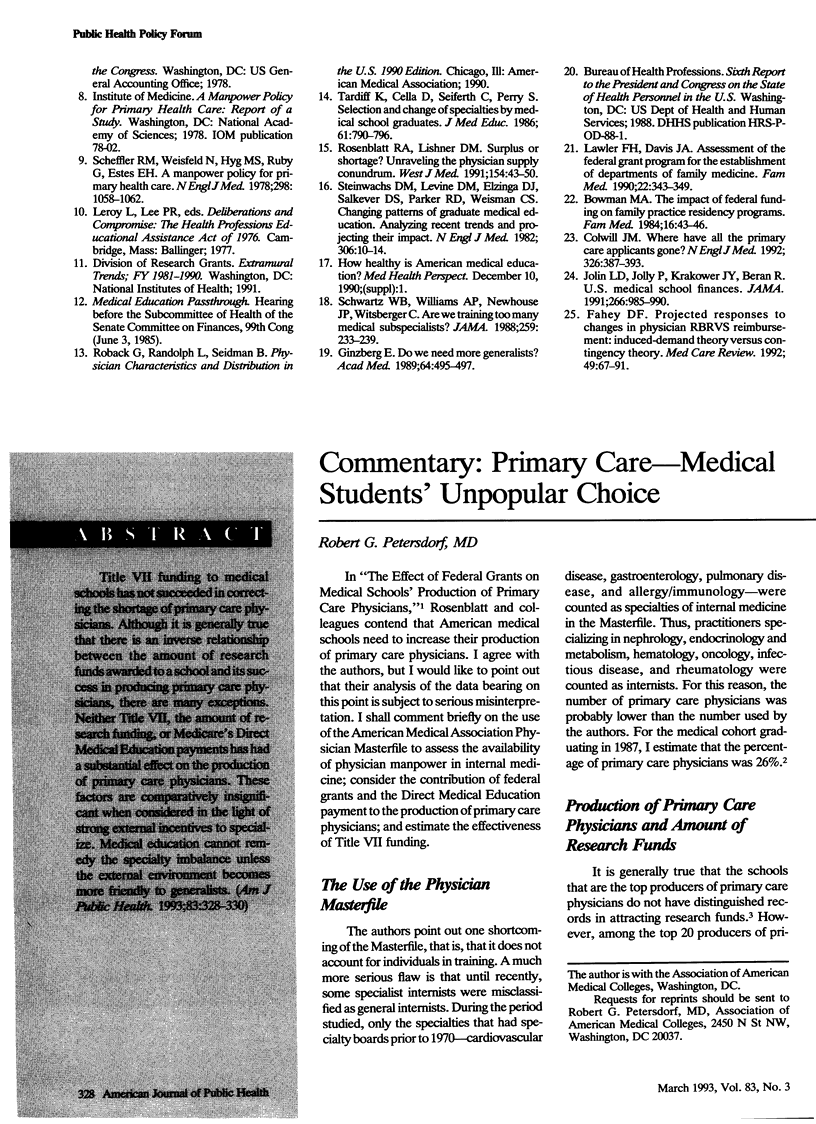

OBJECTIVES. Title VII of the Health Professions Educational Assistance Act of 1976 was created to encourage the production of primary care physicians. This study explored recent trends in the proportion of US medical school graduates entering primary care in relationship to Title VII funding. METHODS. The American Medical Association Physician Masterfile was used to determine the specialty choice of all students graduating from American medical schools between 1960 and 1985. RESULTS. The proportion of graduates entering primary care rose from 19.7% in 1967 to 31.1% in 1976 and remained stable for the subsequent decade. The increase occurred before implementation of Title VII. Rural, state-owned medical schools with departments of family medicine tend to produce a greater proportion of primary care physicians than urban private schools without family medicine departments. CONCLUSIONS. The values of American medical schools and the reward structure of American medical practice favor the production of specialists over primary care physicians. Although Title VII helped to encourage and sustain the development of primary care educational programs at both the medical student and graduate levels, an increase in the proportion of primary care physicians will require fundamental changes.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Fahey D. F. Projected responses to changes in physician RBRVS reimbursement: induced-demand theory versus contingency theory. Med Care Rev. 1992 Spring;49(1):67–91. doi: 10.1177/002570879204900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzberg E. Do we need more generalists? Acad Med. 1989 Sep;64(9):495–497. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolin L. D., Jolly P., Krakower J. Y., Beran R. US medical school finances. JAMA. 1991 Aug 21;266(7):985–990. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.7.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindig D. A., Movassaghi H. The adequacy of physician supply in small rural counties. Health Aff (Millwood) 1989 Summer;8(2):63–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.8.2.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler F. H., Davis J. A. Assessment of the Federal Grant Program for the Establishment of Departments of Family Medicine. Fam Med. 1990 Sep-Oct;22(5):343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt R. A., Lishner D. M. Surplus or shortage? Unraveling the physician supply conundrum. West J Med. 1991 Jan;154(1):43–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler R. M., Weisfeld N., Ruby G., Estes E. H. A manpower policy for primary health care. N Engl J Med. 1978 May 11;298(19):1058–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197805112981905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz W. B., Williams A. P., Newhouse J. P., Witsberger C. Are we training too many medical subspecialists? JAMA. 1988 Jan 8;259(2):233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinwachs D. M., Levine D. M., Elzinga D. J., Salkever D. S., Parker R. D., Weisman C. S. Changing patterns of graduate medical education. N Engl J Med. 1982 Jan 7;306(1):10–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198201073060103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff K., Cella D., Seiferth C., Perry S. Selection and change of specialties by medical school graduates. J Med Educ. 1986 Oct;61(10):790–796. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198610000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]