Abstract

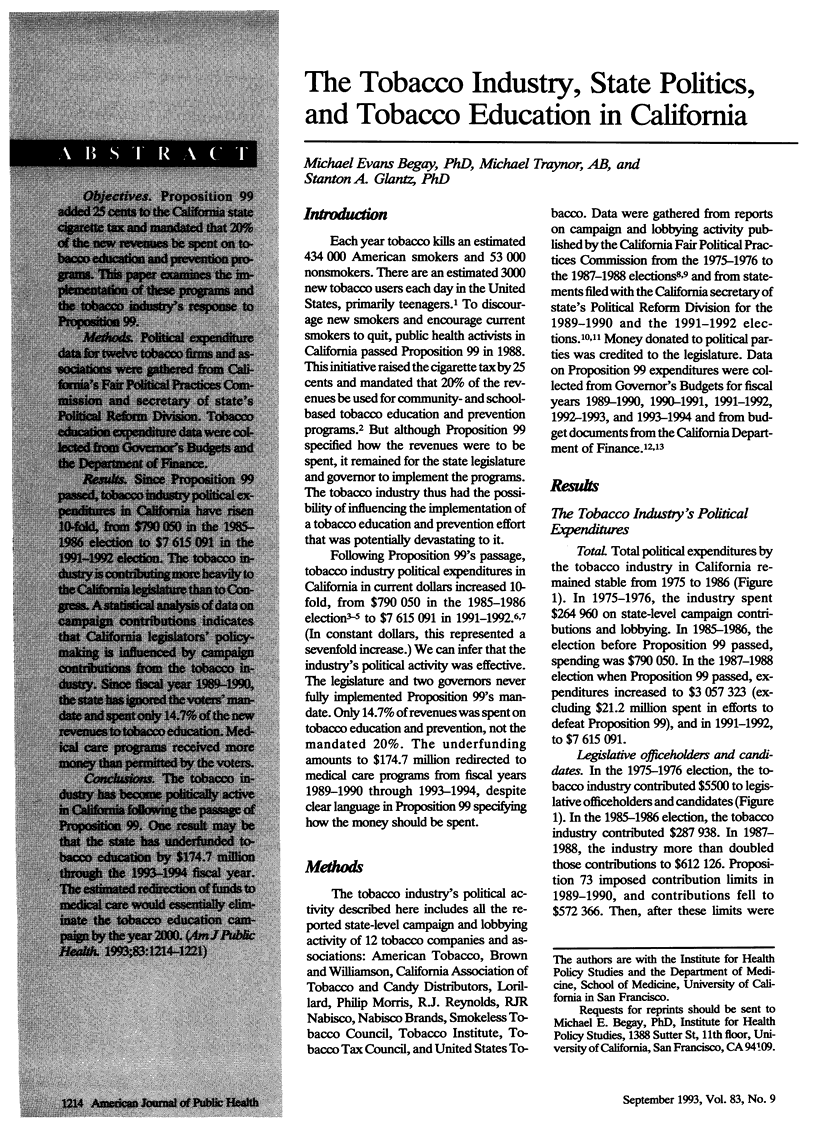

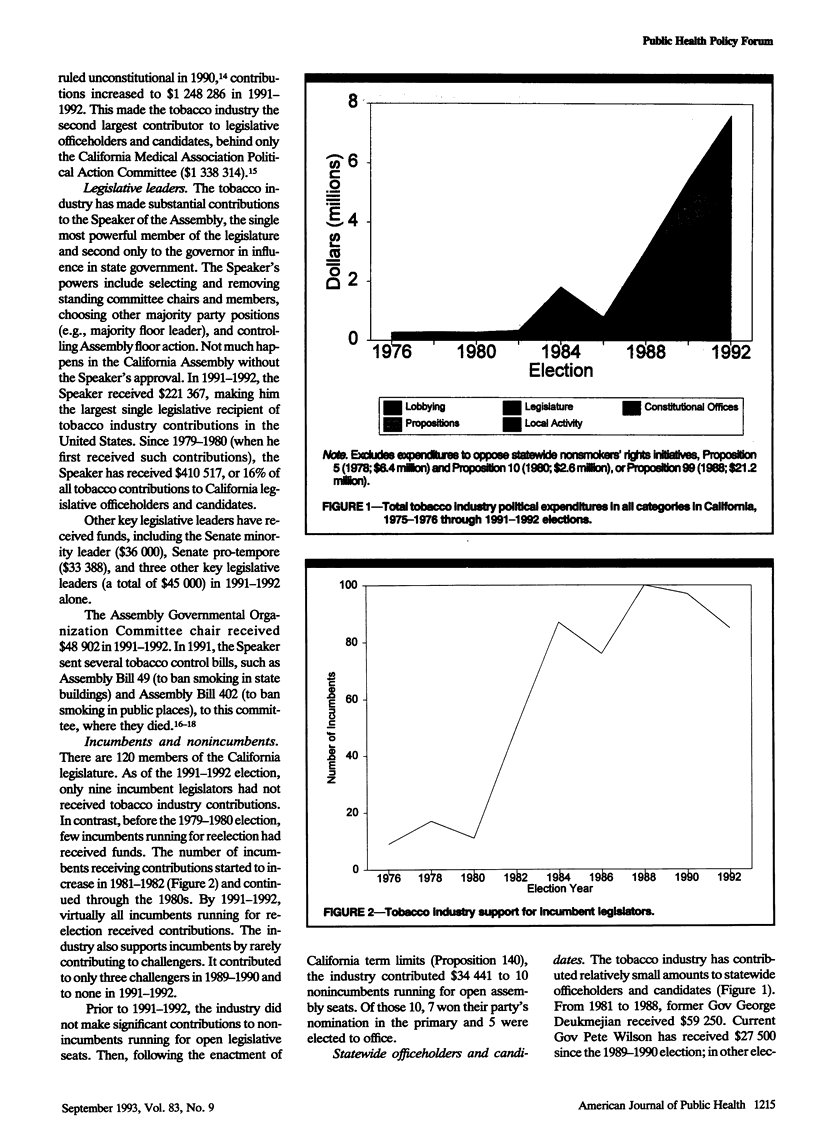

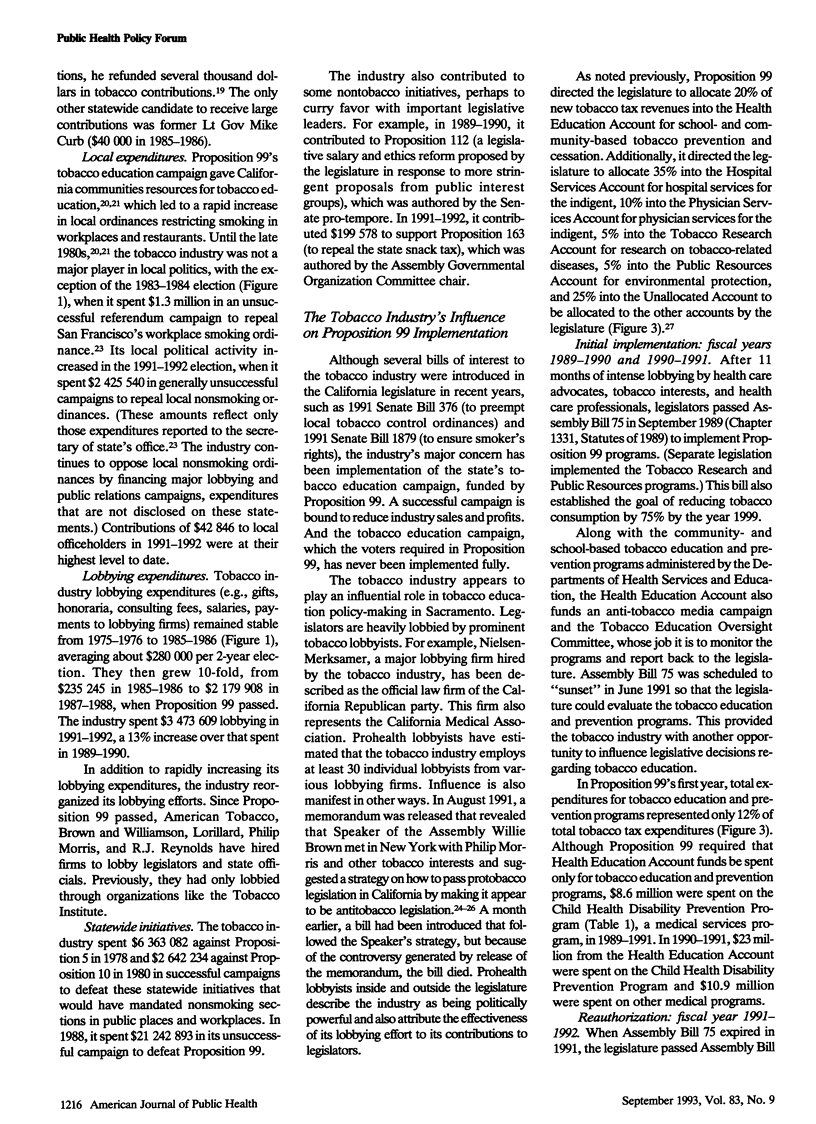

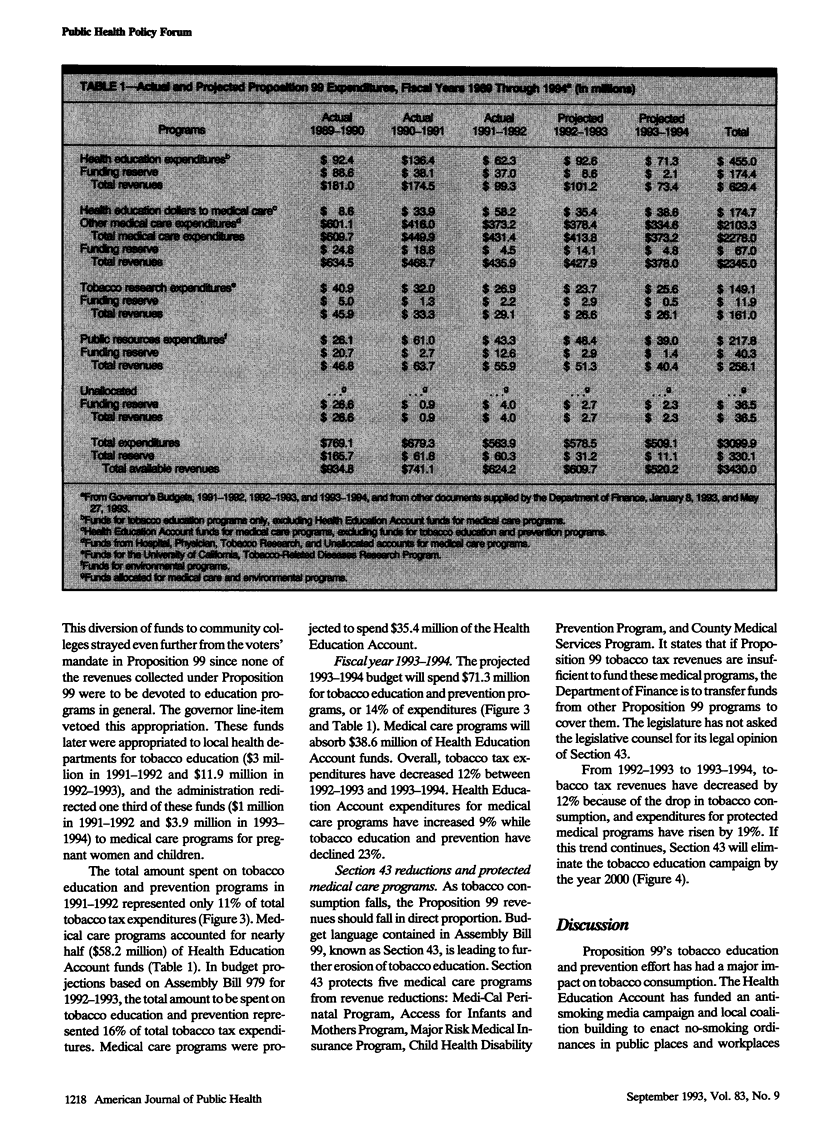

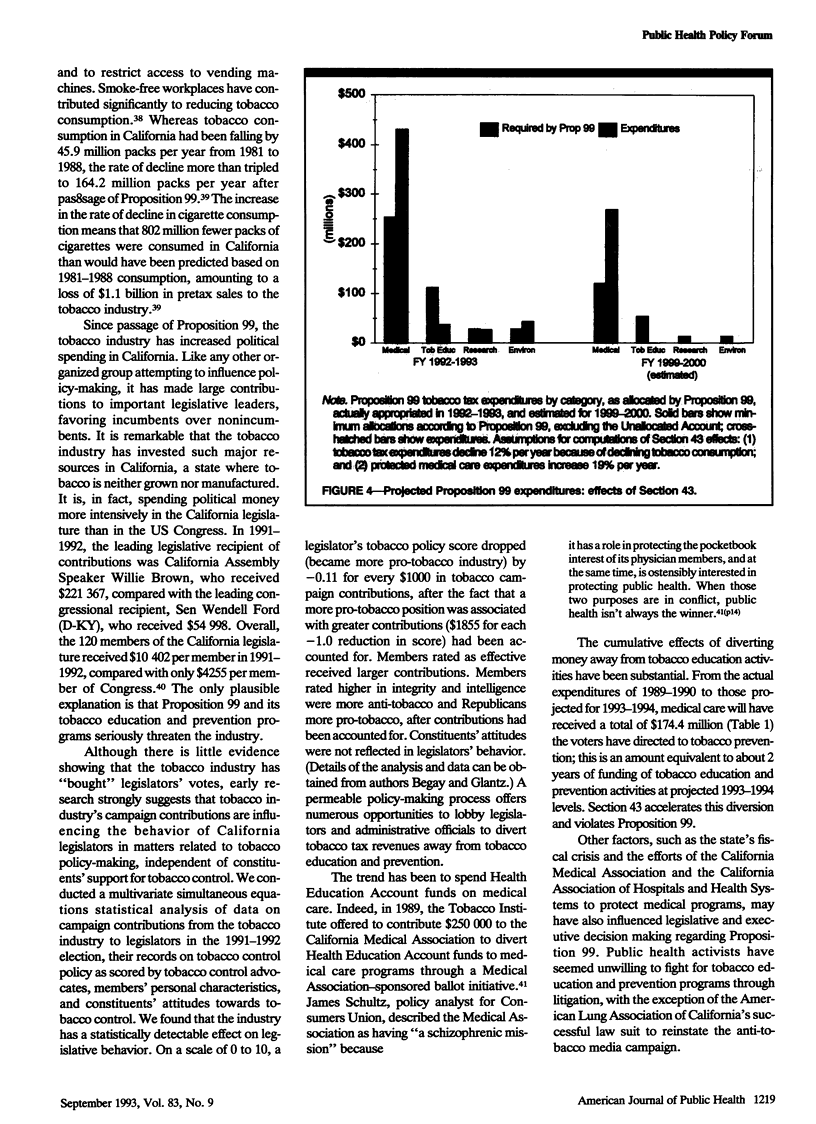

OBJECTIVES. Proposition 99 added 25 cents to the California state cigarette tax and mandated that 20% of the new revenues be spent on tobacco education and prevention programs. This paper examines the implementation of these programs and the tobacco industry's response to Proposition 99. METHODS. Political expenditure data for twelve tobacco firms and associations were gathered from California's Fair Political Practices Commission and secretary of state's Political Reform Division. Tobacco education expenditure data were collected from Governor's Budgets and the Department of Finance. RESULTS. Since Proposition 99 passed, tobacco industry political expenditures in California have risen 10-fold, from $790,050 in the 1985-1986 election to $7,615,091 in the 1991-1992 election. The tobacco industry is contributing more heavily to the California legislature than to Congress. A statistical analysis of data on campaign contributions indicates that California legislators' policy-making is influenced by campaign contributions from the tobacco industry. Since fiscal year 1989-1990, the state has ignored the voters' mandate and spent only 14.7% of the new revenues to tobacco education. Medical care programs received more money than permitted by the voters. CONCLUSIONS. The tobacco industry has become politically active in California following the passage of Proposition 99. One result may be that the state has underfunded tobacco education by $174.7 million through the 1993-1994 fiscal year. The estimated redirection of funds to medical care would essentially eliminate the tobacco education campaign by the year 2000.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bal D. G., Kizer K. W., Felten P. G., Mozar H. N., Niemeyer D. Reducing tobacco consumption in California. Development of a statewide anti-tobacco use campaign. JAMA. 1990 Sep 26;264(12):1570–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flewelling R. L., Kenney E., Elder J. P., Pierce J., Johnson M., Bal D. G. First-year impact of the 1989 California cigarette tax increase on cigarette consumption. Am J Public Health. 1992 Jun;82(6):867–869. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.6.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J. P., Fiore M. C., Novotny T. E., Hatziandreu E. J., Davis R. M. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. Projections to the year 2000. JAMA. 1989 Jan 6;261(1):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels B., Glantz S. A. The politics of local tobacco control. JAMA. 1991 Oct 16;266(15):2110–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick A. A. Court orders California governor to restore antismoking media campaign funding. JAMA. 1992 May 27;267(20):2721–2723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff T. J., Rosbrook B., Pierce J., Glantz S. A. Lower levels of cigarette consumption found in smoke-free workplaces in California. Arch Intern Med. 1993 Jun 28;153(12):1485–1493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]