Abstract

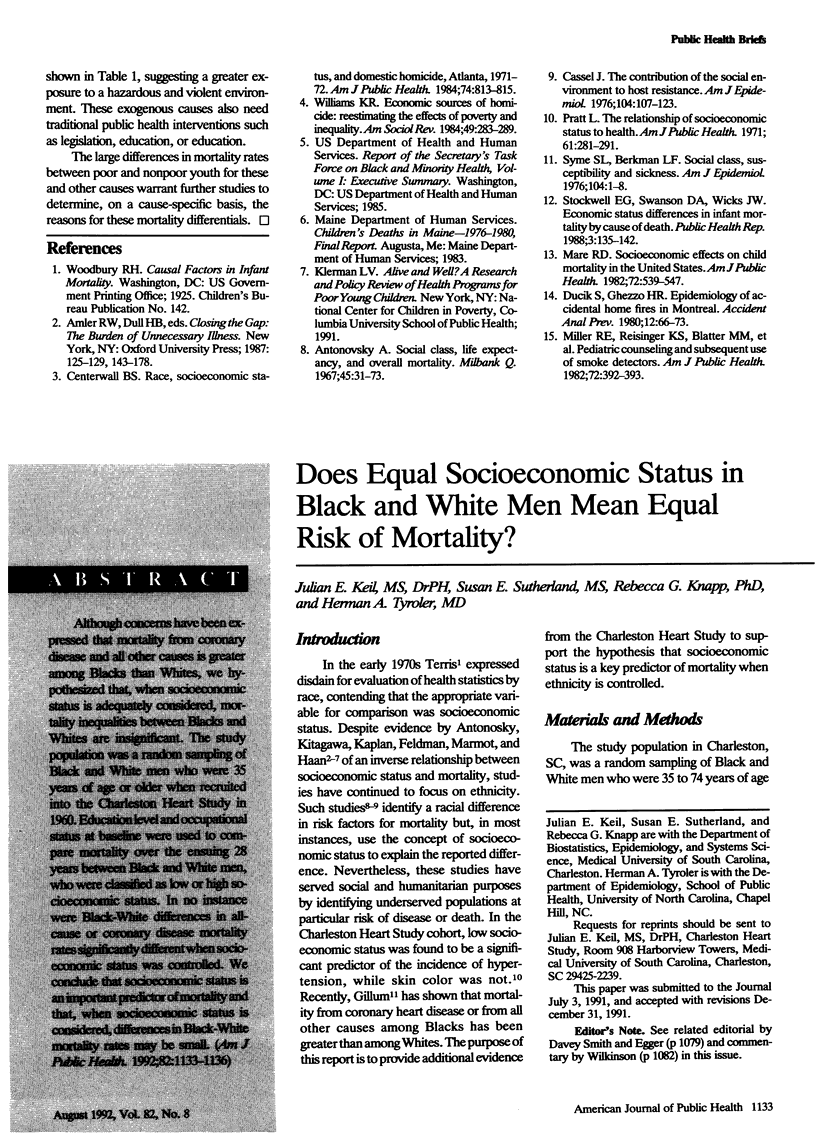

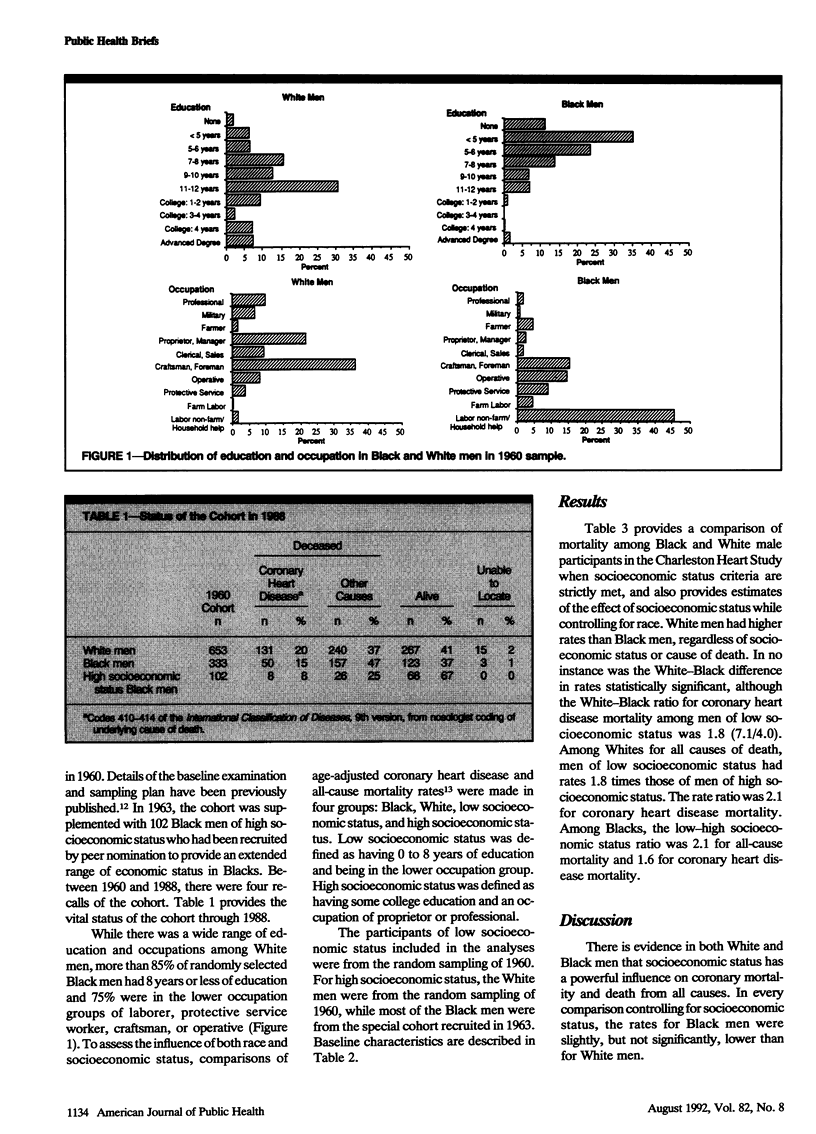

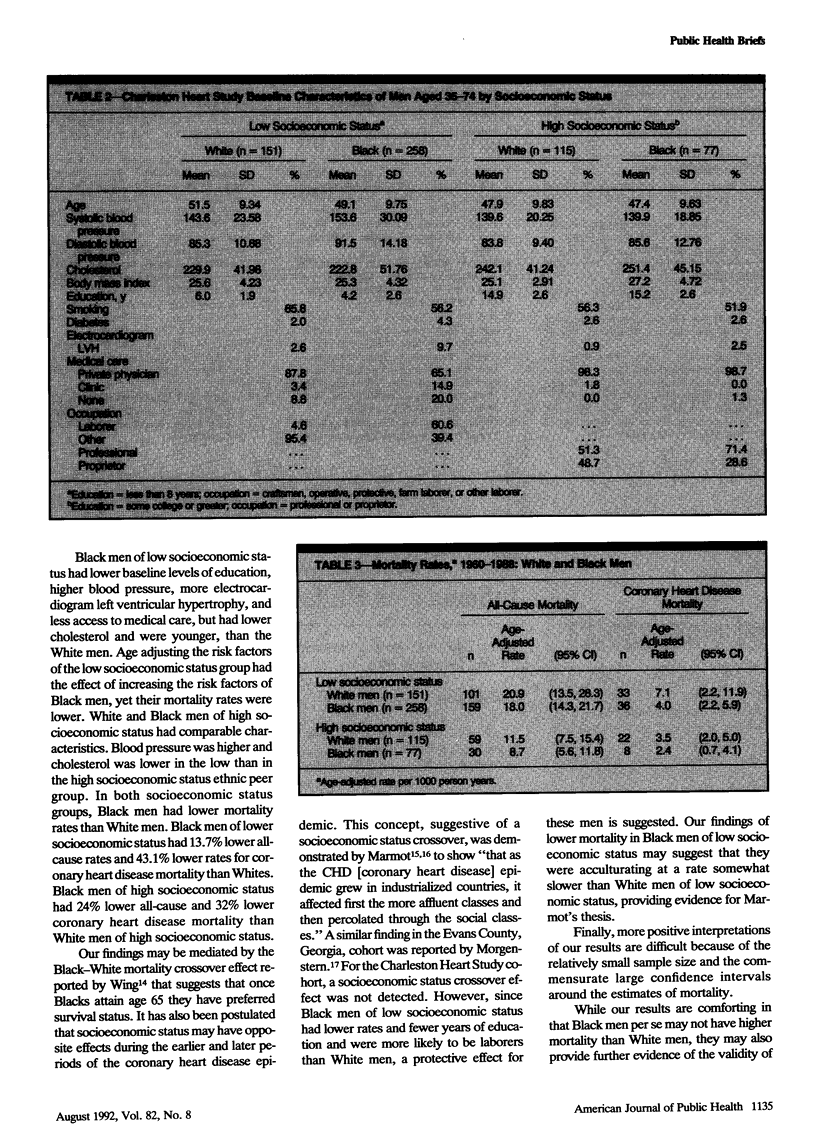

Although concerns have been expressed that mortality from coronary disease and all other causes is greater among Blacks than Whites, we hypothesized that, when socioeconomic status is adequately considered, mortality inequalities between Blacks and Whites are insignificant. The study population was a random sampling of Black and White men who were 35 years of age or older when recruited into the Charleston Heart Study in 1960. Education level and occupational status at baseline were used to compare mortality over the ensuing 28 years between Black and White men, who were classified as low or high socioeconomic status. In no instance were Black-White differences in all-cause or coronary disease mortality rates significantly different when socioeconomic status was controlled. We conclude that socioeconomic status is an important predictor of mortality and that, when socioeconomic status is considered, differences in Black-White mortality rates may be small.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Boyle E., Jr Biological pattern in hypertension by race, sex, body weight, and skin color. JAMA. 1970 Sep 7;213(10):1637–1643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler W. W. Social class, skin color, and arterial blood pressure in two societies. Ethn Dis. 1991 Winter;1(1):60–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J. J., Makuc D. M., Kleinman J. C., Cornoni-Huntley J. National trends in educational differentials in mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 May;129(5):919–933. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil J. E., Tyroler H. A., Sandifer S. H., Boyle E., Jr Hypertension: effects of social class and racial admixture: the results of a cohort study in the black population of Charleston, South Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1977 Jul;67(7):634–639. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.7.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klag M. J., Whelton P. K., Coresh J., Grim C. E., Kuller L. H. The association of skin color with blood pressure in US blacks with low socioeconomic status. JAMA. 1991 Feb 6;265(5):599–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Adelstein A. M., Robinson N., Rose G. A. Changing social-class distribution of heart disease. Br Med J. 1978 Oct 21;2(6145):1109–1112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6145.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Kogevinas M., Elston M. A. Social/economic status and disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 1987;8:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.08.050187.000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern H. The changing association between social status and coronary heart disease in a rural population. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1980 May;14A(3):191–201. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(80)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terris M. Desegregating health statistics. Am J Public Health. 1973 Jun;63(6):477–480. doi: 10.2105/ajph.63.6.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing S., Manton K. G., Stallard E., Hames C. G., Tryoler H. A. The black/white mortality crossover: investigation in a community-based study. J Gerontol. 1985 Jan;40(1):78–84. doi: 10.1093/geronj/40.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]