Abstract

The timing of postembryonic developmental programs in Caenorhabditis elegans is regulated by a set of so-called heterochronic genes, including lin-28 that specifies second larval programs. lin-66 mutations described herein cause delays in vulval and seam cell differentiation, indicating a role for lin-66 in timing regulation. A mutation in daf-12/nuclear receptor or alg-1/argonaute dramatically enhances the retarded phenotypes of the lin-66 mutants, and these phenotypes are suppressed by a lin-28 null allele. We further show that the LIN-28 protein level is upregulated in the lin-66 mutants and that this regulation is mediated by the 3′UTR of lin-28. We have also identified a potential daf-12-response element within lin-28 3′UTR and show that two microRNA (miRNA) (lin-4 and let-7)-binding sites mediate redundant inhibitory activities that are likely lin-66-independent. Quantitative PCR data suggest that the lin-28 mRNA level is affected by lin-14 and miRNA regulation, but not by daf-12 and lin-66 regulation. These results suggest that lin-28 expression is regulated by multiple independent mechanisms including LIN-14-mediated upregulation of mRNA level, miRNAs-mediated RNA degradation, LIN-66-mediated translational inhibition and DAF-12-involved translation promotion.

Keywords: heterochronic, lin-66, microRNA, translational inhibition, vulval development

Introduction

Although spatial regulation of developmental pattern formation has attracted extensive research in the past two decades, study of temporal regulation has been limited to a few systems and remains a relatively open research field. A number of heterochronic genes have been shown to regulate developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Some of the key players, including the two first identified microRNAs (miRNA) lin-4 and let-7, are evolutionarily conserved (Rougvie, 2001; Pasquinelli and Ruvkun, 2002; Ambros, 2004). lin-14 and lin-28 are two critical timing regulators of stage-specific developmental programs, as opposite heterochronic phenotypes are associated with their loss-of-function (lf) and gain-of-function (gf) mutations. lin-14 acts to specify the first larval (L1) developmental program: the L1 program is skipped in lin-14 (lf) mutants but reiterated in lin-14 (gf) mutants (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984). Similarly, lin-28 acts to specify the second larval (L2) developmental program: the L2 program is skipped in lin-28 (lf) mutants but reiterated in animals expressing a lin-28 (gf) transgene (Moss et al, 1997). The LIN-14 and LIN-28 proteins are abundant from the late embryo to L1 stage, but their expression decreases after L2 and is further reduced to undetectable levels in the L4 and adult stages (Wightman et al, 1993; Moss et al, 1997; Seggerson et al, 2002).

The heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes an miRNA that acts in later larval and adult stages to repress the expression of lin-14 and lin-28 (Lee et al, 1993; Wightman et al, 1993; Moss et al, 1997). In addition, lin-14 and lin-28 are also known to positively regulate each other (Arasu et al, 1991; Moss et al, 1997). lin-28 encodes an approximately 25-kDa protein with two types of RNA-binding motifs: a so-called cold shock domain and a pair of retroviral-type CCHC zinc-finger domains (Moss et al, 1997). The mammalian homologues of lin-28 are expressed at early developmental stages and they have a long 3′UTR with sequences that are complementary to the lin-4 and let-7 miRNA homologues (Moss and Tang, 2003). lin-14 encodes a transcription factor (Ruvkun and Giusto, 1989).

Previous work indicated that lin-4 activity alone is not sufficient to suppress the expression of lin-28 in later larval stages (Seggerson et al, 2002). One other gene known to be involved in regulating lin-28 is daf-12 that encodes a nuclear hormone receptor (Antebi et al, 2000). A recessive gf mutation, daf-12 (rh61), causes a prominent developmental delay phenotype and accumulation of LIN-28 protein in late stages, although the delay phenotypes were not associated with a null allele (Antebi et al, 1998, 2000; Seggerson et al, 2002).

Key timing regulators such as lin-4, lin-14 and lin-28 have been shown to regulate the timing of vulval cell division (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984; Euling and Ambros, 1996). lin-14 (lf) and lin-28 (lf) mutations cause precocious vulval cell divisions: vulval cells divide one stage earlier than in wild type (WT), presumably owing to skipping the L1 and L2 programs in the lin-14 (lf) and lin-28 (lf) mutants, respectively. On the other hand, lin-4 (lf) and lin-14 (gf) mutations cause retarded or eliminated vulval cell divisions. C. elegans vulval differentiation is regulated by several well-known signalling pathways including the RTK/RAS/MAPK pathway that induces three of six vulval precursor cells to become vulval cells (Sternberg, 2005). LIN-31 and LIN-1 are two transcription factors that act at the end of the signalling pathway to specify vulval cell fate.

In an effort to identify genes acting downstream or with lin-31 to specify vulval cell fate, we have carried out a genetic screen for suppressors of the multivulva (Muv) phenotype of lin-31 (lf). Interestingly, we found a number of suppressors that displayed heterochronic mutant phenotypes. These mutations are alleles of five genes including ain-1 (Ding et al, 2005), alg-1 and lin-66 (this study). In this paper, we describe the genetic and molecular analysis of lin-66 and provide evidence that lin-66 likely acts to inhibit lin-28 translation. We also analyzed the roles of daf-12, miRNA and lin-14 in regulating lin-28 expression, and show they mediate multiple independent mechanisms.

Results

lin-66 (lf) mutations suppress the multivulva phenotype of lin-31 (lf)

In our screens for suppressors of the Muv phenotype of lf alleles of lin-31 (Ding et al, 2005; Morita et al, 2005), two of the 12 mutations, ku423 and ku424, displayed similar phenotypes and were mapped to the same chromosome region. In the lin-31 (n301) mutant background, ku423 or ku424 causes a fully penetrant egg-laying defect in hermaphrodites (n=244 and 160, respectively). When these two alleles were isolated away from the lin-31 (n301) mutation, they displayed a striking larval lethality; 95% of the mutants die at the late L4 stage (n=256), accompanied with a burst of the gonad through the vulva (Figure 1A). This lethal phenotype is very similar to that of let-7(lf) mutants. A small percentage of the homozygous animals escaped from lethality but all of them failed to lay eggs.

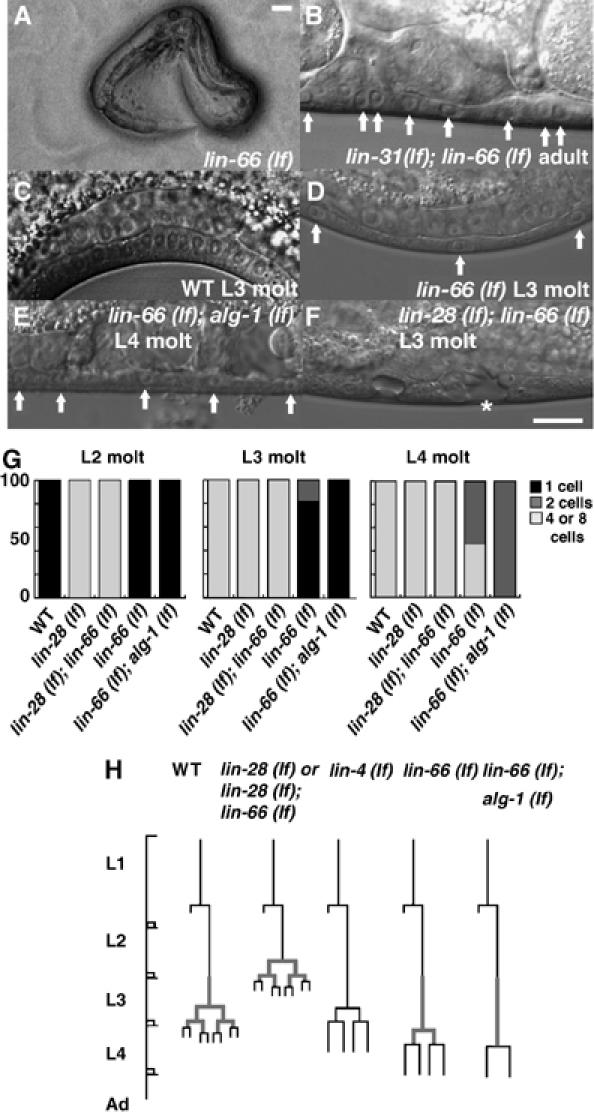

Figure 1.

lin-66 (lf) causes defective vulval development. (A) A lin-66 (ku423) L4 dying larva with the gonad bursting through the vulva. Ninety-five percent of the homozygous mutants from heterozygous mother die at this stage. Bar, ∼50 μm. (B) A lin-31 (n301); lin-66 (ku423) adult animal showing that Pn.p cells failed to differentiate into vulval cells and form vulval invaginations. Arrows indicate the Pn.p derivatives. (C, D) L3 larva of WT and lin-66 (ku423) mutants showing that the first round of vulval cell divisions was delayed in the mutant animals. Arrows in (D) indicate one-cell stage Pn.p cells. (E) An L4 molting larva showing that the vulval cell division is severely delayed in the lin-66 (ku423); alg-1 (gk214) double mutants, as the Pn.p cells (arrows) are still at the two-cell stage. Bar, ∼10 μm. (F) A lin-28 (n719); lin-66 (ku423) double mutant L3 larva displaying a precocious vulval division phenotype. The vulval morphology in this worm is normally seen only in L4 larva. (G) Graphical representations of the percent of vulval cells at each division stage (derived from P5–7.p) at three larval stages. Twenty or more animals were examined for each strain at each developmental stage. (H) Schematic summary of the timing of the division of Pn.p cells destined to become vulval cells in indicated strains. Thick line indicates the egl-17∷GFP expression in P6.p.

lin-66 encodes a novel protein that is ubiquitously expressed

Both ku423 and ku424 are recessive alleles. Using single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mapping, DNA-mediated rescue and DNA sequencing (Materials and methods), we determined that B0513.1, a transcription unit annotated by the genome project (WormBase.com), is the lin-66 gene (Supplementary Figure S1). ku423 and ku424 were determined to contain a nonsense mutation in exon 5 (Q364 to stop) and a first exon splicing mutation (GT to AT), respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). The molecular lesions of the two mutations and the fact that each displayed indistinguishable phenotypes strongly suggest that both ku423 and ku424 are null or strong lf mutations. We named the gene defined by these two mutations as lin-66 (lineage defective 66). ku423 is used for most of the genetic analysis.

lin-66 encodes a 627-amino-acid novel protein. LIN-66 is highly homologous (80% identity in amino acids) to a protein in the closely related nematode species C. briggsae. To assess the expression pattern of lin-66, we constructed a transgenic strain that expresses a lin-66∷GFP translational fusion protein (Materials and methods). This transgene fully rescued the lin-66 (lf) phenotypes (data not shown). The GFP expression was detected in many tissues throughout the development (Supplementary Figure S1). The fusion protein was cytoplasm-localized (Supplementary Figure S1), which is consistent with its activity on the lin-28 3′UTR and a role in translational inhibition (see below).

lin-66 (lf) mutations cause a delay or elimination of vulval cell divisions

To assess the cause of the suppression of the lin-31 (lf) Muv phenotype that was scored under a dissecting microscope, we followed the cell lineage of P5.p, P6.p and P7.p (P(5–7).p) in lin-31 (n301); lin-66 (ku423) double mutants using Nomarski optics. In WT worms, P(5–7).p cell lines start dividing during the L3 stage (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977) (Figure 1C and H). In contrast, in lin-31 (n301); lin-66 (ku423) double mutants, cell divisions of these cells often started during the late L4 stage or did not occur at all (Figure 1B). This phenotype is similar to the developmental delay phenotype associated with certain heterochronic mutants such as the lin-4 (lf) mutants (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984). Therefore, lin-66 (lf) likely suppresses the Muv phenotype of lin-31 (lf) by delaying or eliminating the cell division of vulval cells.

We then analyzed the phenotypes of lin-66 (ku423) single mutant animals. lin-66 (ku423)/lin-66 (ku423) homozygous progeny from lin-66 (ku423)/+ heterozygous mothers displayed a weaker cell division delay in P5.p, P7.p and their derivatives when compared with the ku423/ku423 progeny from ku423/ku423 mothers (data not shown). This weaker phenotype is consistent with the existence of maternal lin-66 gene product in the homozygous animals from the heterozygous mothers. Interestingly, ku423/ku423 progeny from ku423/+ mothers displayed a stronger lethality at the late L4 stage (95%, n=256) when compared with the ku423/ku423 progeny from ku423/ku423 mothers (46%, n=317). As ku423/ku423 animals are egg-laying defective, resulting in the progeny hatched internally experienced starvation after the hatching, the weaker lethality of the ku423/ku423 animals from ku423/ku423 animals may be due to starvation-induced phenotypic suppression (Rougvie, 2005).

We further analyzed vulval cell divisions of lin-66 (ku423) homozygotes from the homozygous mothers under Nomarski optics. In WT hermaphrodites, the first round of cell divisions of P(5–7).p occur during the mid-L3 stage and the next round of cell divisions occur at the L3 molting stage. At the L4 molting stage, P(5–7).p derivatives terminally differentiate into vulval cells. (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977) (Figure 1C and H). We observed that P(5–7).p cell divisions were severely delayed or eliminated in lin-66 (ku423) animals (Figure 1D and H). For example, 82% of P(5–7).p cells failed to complete the first cell division (stayed at the one-cell stage) in the L3 molt (Figure 1D and H). Moreover, in the lin-66 (ku423) mutants, most of the P(5–7).p cells failed to complete cell divisions and no vulval structure was observed in adults (Figure 1G; data not shown).

lin-66 (lf) mutants display a retarded heterochronic phenotype during seam cell differentiation

In WT worms, the lateral hypodermal seam cells divide with a stem-cell-like pattern during larval stages. They then exit the cell cycle and terminally differentiate after L4 molting—a process termed as the ‘larval to adult (L/A) switch' (Ambros, 1989) (Figure 2G). These cells secrete a cuticular structure known as the lateral alae during the adult stage. We observed that lin-66 (lf) animals failed to generate alae after the L4 molt (Table I), suggesting that lin-66 has a role in regulating seam cell division and differentiation.

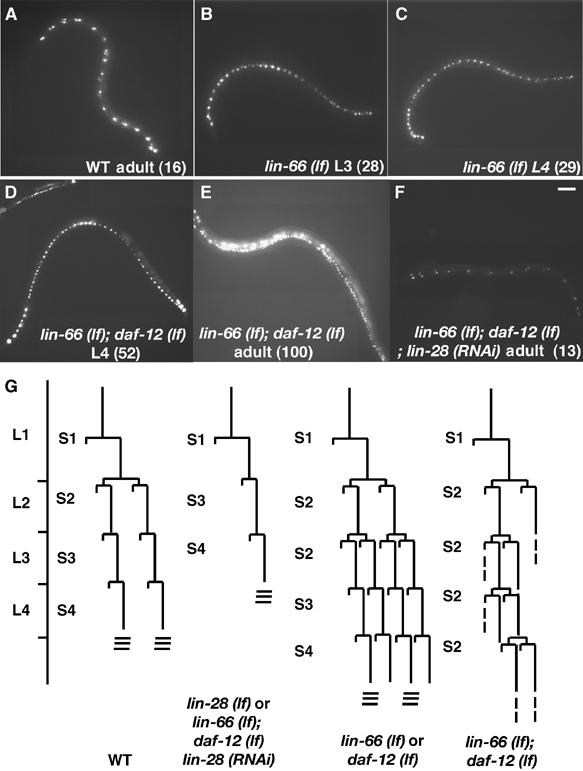

Figure 2.

Effect of lin-66 (lf) and its interaction with daf-12 and lin-28 mutations on seam cell differentiation. (A–F) Fluorescent images of lateral sides of animals of genotypes and stages as indicated. The fluorescence indicates expression of SCM-1∷GFP that marks the seam cells. (n), number of GFP-positive cells counted in each image. ku423, rh61 and n719 are alleles of lin-66, daf-12 and lin-28, respectively. Bar, ∼50 μm. (G) Schematic summary of the differentiation pattern of certain seam cells (V1–V4, V6 and (H) during post-embryonic development. The lin-28 (lf) and daf-12 (rh61) pattern was reported previously (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984; Antebi et al, 1998). Sn refers to Ln-specific cell lineage/program in hypodermal cell differentiation (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984). Three horizontal lines at the end of lineage stand for adult alae formation.

Table 1.

Genetic interaction of lin-66 with known heterochronic genes on alae formation

| Genotypea | Alae synthesis (%) (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| L3 molt | L4 molt | Ad/L5 moltb | |

| WT (N2) | 0 (20) | 100 (20) | ND |

| lin-66 (ku423) | ND | 0 (14) | 100c (41) |

| lin-31 (n301); lin-66 (ku423) | ND | 0 (31) | 100c (15) |

| lin-31 (n301) | ND | 100% (31) | ND |

| lin-14 (ma135) | 100 (23) | ND | ND |

| lin-14 (ma135); lin-66 (ku423) | 0 (29) | 100c (25) | ND |

| lin-28 (n719) | 100 (18) | ND | ND |

| lin-28 (n719); lin-66 (ku423) | 100 (52) | ND | ND |

| hbl-1 (RNAi) | 83 (35) | 100c (15) | ND |

| lin-66 (ku423); hbl-1 (RNAi) | 0 (24) | 100c (35) | ND |

| lin-41 (ma104) | 60c (25) | 100c (25) | ND |

| lin-41 (ma104); lin-66 (ku423) | 33c (33) | 100c (36) | ND |

| lin-42 (n1089) | 80c (50) | 100c (38) | ND |

| lin-42 (n1089); lin-66 (ku423) | 3c (32) | 100c (21) | ND |

| lin-29 (n333) | ND | 0 (25) | 0 (28) |

| lin-29 (n333); lin-66 (ku423) | ND | 0 (28) | 0 (30) |

| lin-4 (e912) | ND | 0 | 0 |

| daf-12 (rh61) | ND | 100c (41) | ND |

| lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (rh61) | ND | 0 (32) | 0 (42) |

| alg-1 (ok214) | ND | 59% (49) | 100% (16) |

| lin-66 (ku423); alg-1 (ok214) | ND | ND | 0% (33) |

| lin-46 (ma164) | ND | 100 | 100% |

| lin-66 (ku423); lin-46 (ma164) | ND | ND | 0% (26) |

| aThe newly synthesized cuticle was examined for the presence of alae by Nomarski microscope. | |||

| bAdult stage or fifth molting stage for retarded mutants that undergo an extra molting stage. | |||

| cSome animals had gaps in their alae. | |||

| ND, not determined. | |||

In WT larvae, the majority of the seam cells undergo a single asymmetric cell division, after which the anterior daughter joins the hypodermal syncytium and the posterior daughter remains a seam cell (Figure 2G). Therefore, these divisions do not result in changes in seam cell numbers. However, during the L2 stage, certain seam cells (V1–4, V6, H1) undergo one round of symmetric cell divisions before the asymmetric cell division, which results in an increase of the number of seam cells on each side of the animal by six (Rougvie, 2001) (Figure 2G). At the L/A switch, WT animals usually have 16 unfused seam cells (Figure 2A). Mutations in heterochronic genes often alter the seam cell division pattern. For example, lin-4 (lf) displays a retarded mutant phenotype in which the animals repeat the L1 seam cell division program (never entering the L2 stage). Consequently, there are only 10 seam cells even at the adult stage. In contrast, lin-28 (lf) displays a precocious phenotype in which the animals skip the L2 seam cell division program and instead enter the L3 program prematurely. By eliminating the cell number duplication for the six seam cells at the L2 stage, the seam cell number for L3, L4 and adult animals is also reduced to 10 (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984; Pepper et al, 2004) (Table II). Consistent with the retarded phenotype in the vulval lineage, lin-66 (lf) mutants displayed a retarded seam cell differentiation phenotype, based on the observations using SCM∷GFP(QwIS79) as a seam cell marker (Koh and Rothman, 2001). lin-66 (ku423) animals had a normal seam cell number at L1 and L2, but at the L3 stage seam cell numbers continued to increase to 29 on average, indicating that some of the cells divide symmetrically as in the L2 stage (Figure 2B and C and Table II). This result is consistent with the idea that the L2 seam cell program is reiterated in the L3 stage in lin-66 (lf) mutants.

Table 2.

lin-66 (lf);daf-12 (rh61) and lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) double mutants display a strong L2 reiteration phenotype

| No. of SCM∷GFP-positive cells/lateral side at each stage (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | Ad/L5 | |

| WT | 10 (7) | 16 (12) | 16 (11) | 16 (17) | 16 (19) |

| lin-66 (ku423) | 10 (22) | 16.5 (59) | 28.6 (39) | 29.1 (50) | 29.1 (25) |

| daf-12 (rh61) | 10 (10) | 16.6 (22) | 25.7 (21) | 26.6 (25) | 27.9 (14) |

| lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (rh61) | 10 (12) | 17.0 (20) | 28.8 (25) | 50.6 (28) | 78 (6) |

| daf-12 (rh61rh411) | 10 (8) | 16.7 (8) | 19 (7) | 20.7 (14) | 21.5 (22) |

| lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (rh61rh411) | 10 (6) | 16.2 (6) | 28.7 (6) | 49.4 (13) | 93 (7) |

| daf-12 (m20) | 10 (5) | 16.3 (8) | 18.3 (7) | 21 (7) | 19.6 (19) |

| lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (m20) | 10 (8) | 16.5 (6) | 28.4 (7) | 48.7 (6) | 83.7 (10) |

| lin-4 (e912) | 10 (10) | 10 (12) | 10 (14) | 10 (6) | 10 (10) |

| lin-66 (ku423); alg-1 (ok214) | 9.8 (13) | 16.7 (12) | 27.7 (10) | 45.2 (6) | 83.2 (12) |

| lin-28 (RNAi) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 11.0 (25) |

| lin-66 (ku423); alg-1 (ok214); lin-28 (RNAi) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 11.7 (20) |

| lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (rh61); lin-28 (RNAi) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 12.3 (13) |

| Seam cell nuclei were counted on one side of the animal of the indicated genotype and stage. | |||||

| RNAi was performed by injecting dsRNA into the adult gonad. The seam cell number of the next generation was counted. | |||||

| ND, not determined. | |||||

The defect in seam cell division, failure in alae formation, lethality and the vulval division defects were all suppressed when the lin-66 (lf) animals developed through the alternative dauer larval stage (data not shown). Phenotypic suppression by progression through the dauer stage is a distinctive feature of many heterochronic mutants (Liu and Ambros, 1989).

lin-66 and daf-12 double mutants display a strong retarded seam cell phenotype

daf-12 encodes a nuclear receptor that has been shown to be involved in the heterochronic genetic pathway (Antebi et al, 1998, 2000; Grosshans et al, 2005). daf-12 (rh61) was thought to be a recessive gf mutation that causes a retarded seam cell defect similar to that of lin-66 (lf) (repeating the L2 program once; Figure 2G; Table II). To examine the functional relationship between daf-12 and lin-66, we constructed and examined lin-66 (lf); daf-12 (rh61) double mutants. If lin-66 and daf-12 function in a linear pathway, the double mutant animals would be expected to display the same phenotype as that of a single mutant because lin-66 (ku423) is most likely a null allele. Strikingly, in lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (rh61) double mutants, the seam cell number continued to increase during the L3, L4 and adult stages to about 100 cells, indicating that the L2 program was repeated multiple times in the double mutants (Figure 2D and E; Table II). Consequently, lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (rh61) double mutants never generate the adult alae even in the L5 molt (Table I). We have also constructed double mutants containing lin-66 (lf) and two likely daf-12 null alleles, rh61rh411 and m20 (Antebi et al, 2000). Each of the two daf-12(null) alleles alone caused a small increase in seam cell number in late larval and adult stages, whereas both alleles drastically enhanced the seam cell phenotype of the lin-66 mutation (Table II), consistent with a role of daf-12(+) in inhibiting the L2 program (see Discussion). These results suggest that these two genes act through parallel pathways to regulate the timing of seam cell differentiation.

lin-66 acts in parallel to alg-1/argonaute in regulating developmental timing

In C. elegans, alg-1 and alg-2 encode members of the argonaute protein family that are part of the RISC complexes involved in miRNA or siRNA maturation and function (Grishok et al, 2001; Bartel, 2004). ALG-1 and ALG-2 are highly homologous to each other and were shown to be specifically involved in miRNA functions including miRNA-mediated timing regulation (Grishok et al, 2001). Injection of the full-length alg-1 dsRNA, which is likely to partially inactivate alg-2, has been shown to cause the reiteration of the L2 seam cell division program at L3 and an increase in the average number of seam cells from 16 to 21 (Grishok et al, 2001; Bartel, 2004). We have also isolated an alg-1 allele in the same screen that isolated lin-66 alleles. This mutation, ku421, was determined to have a nonsense mutation in the first exon and is thus likely to be another null or severe lf allele. However, neither an alg-1 nor an alg-2 null allele causes a dramatic increase in seam cell numbers in later larval stages (Grishok et al, 2001) (data not shown).

We investigated the relationship of lin-66 with alg-1 and alg-2. Strikingly, a lin-66 (ku423); alg-1 (gk214) double mutant displayed a strong L2 reiteration of the seam cell phenotype similar to that of the lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (rh61) double mutant (Table II). In addition, the alg-1 allele also significantly enhanced the vulval cell division delay phenotype of lin-66 (ku423); 100% of P(5–7).p cells at the L3 molting stage were at the one-cell stage and 100% of the cells at the L4 molting stage were at the two-cell stage (Figure 1E, G and H; Table II).

These results suggest that lin-66 may also function in parallel to alg-1 to regulate developmental timing (see Discussion). In comparison, double mutants containing lin-66 (lf) and a null allele of alg-2 (ok304) displayed a seam cell phenotype that is similar to that of the lin-66 (lf) single mutant. This result may suggest that the alg-2 function, which overlaps with part of the alg-1 function (Grishok et al, 2001), plays a less prominent role in specification of the L2 program. This, however, does not exclude a possibility that alg-2 is involved in the lin-66-mediated function.

RTK/RAS-regulated egl-17∷GFP expression in vulval precursor cells appears to be normal in lin-66 mutants

We have shown that in lin-66 (lf) single and lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) double mutants, the first round of cell divisions of P(5–7)p cells was delayed. This delay could be due to a delay or impairment of the RTK/RAS signalling activity that induced vulval division and differentiation. To investigate this possibility, we analyzed the expression of egl-17∷GFP in lin-66 (lf) and lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) mutants. In WT animals, egl-17∷GFP expression can be detected at the early L3 stage in the P6.p cell and this expression is in response to RTK/RAS signalling (Burdine et al, 1998; Ambros, 1999). We observed normal egl-17∷GFP expression in P6.p at the early L3 stage in lin-66 (lf) and lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) mutants (Supplementary Figure S2), even though the vulval cell divisions were delayed in these strains. This result suggests that in the lin-66 (lf) and in lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) mutants, the timing of the RTK/RAS signalling event was not obviously altered.

lin-66 acts upstream of lin-28 to regulate developmental timing

Genetic properties of lin-28 and lin-66 suggest that these two genes may interact to regulate L2 programs. Not only is the lin-66 (lf) mutant seam cell phenotype (L2 repeating once) opposite that of lin-28 (lf) (L2 bypassing), the lin-66 (lf); daf-12 (rh61) double mutant seam cell phenotype (L2 reiteration multiple times) is similar to the gf mutant phenotype of overexpressing lin-28 (Moss et al, 1997). We thus examined the epistatic relationship between the likely null mutations in the two genes. We found that a lin-28 (n719); lin-66 (ku423) mutant displayed the same seam cell phenotype as that of lin-28 (n719), suggesting that lin-28 acts either downstream of or in parallel to lin-66 to specify the L2 seam cell program. We also examined the genetic interaction between the two genes in vulval cells. lin-28 (lf) mutations were previously shown to cause a precocious mutant phenotype (Euling and Ambros, 1996). We found that the delay of vulval cell divisions lin-66 (lf) was also suppressed by the lin-28 (n719) allele, a result consistent with the idea that lin-66 acts upstream of lin-28 (Figure 1F).

It has previously been shown that the lin-28 (lf) mutant phenotype in seam cells was also epistatic to that of daf-12 (rh61) (Antebi et al, 1998) and that LIN-28 protein expression was increased in daf-12 mutants (Seggerson et al, 2002). Strikingly, the multiple L2 repeat phenotype of the lin-66 (ku423); daf-12 (rh61) double mutant was completely suppressed by RNAi of lin-28 (Figure 2F, Table II). These results, when combined with the genetic interaction data between lin-66 and daf-12, are consistent with a model in which daf-12 and lin-66 act in parallel to regulate the activity of lin-28 (Figure 3).

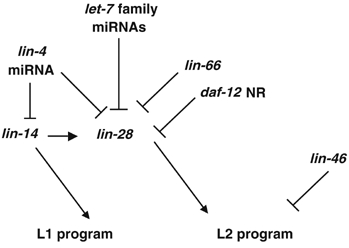

Figure 3.

lin-28 activity is regulated by multiple factors. The functional relationships between the genes shown in the figure are based on genetic data from previous analyses (see Seggerson et al, 2002) and this study. An arrow indicates positive regulation, whereas a T-bar indicates negative regulation. NR, nuclear receptor.

As mentioned above, lin-28 (lf) mutations cause a precocious phenotype in which seam cells bypass the L2 program. In comparison, lin-14 (lf) causes a different precocious phenotype: the seam cells bypass the L1 program, which is opposite to that of lin-4 (lf) (reiterating the L1 program) (Lee et al, 1993; Wightman et al, 1993). Furthermore, both lin-14 and lin-28 have been shown to be regulated by lin-4 miRNA (Lee et al, 1993; Wightman et al, 1993; Moss et al, 1997). We then examined the interaction between lin-66 and lin-14. The lin-66 (ku423); lin-14 (lf) double mutants displayed a seam cell phenotype that reflected a mutual suppression of mutating the two genes (Table I). This suggests that lin-66 does not act upstream of lin-14, which is consistent with the hypothesis that lin-66 acts to regulate lin-28.

Next, we analyzed the genetic interaction between lin-66 and hbl-1, knowing that hbl-1 also regulates the L2/L3 transition and is regulated by the let-7-like miRNAs, mir-48, mir-84 and mir-241 (Abrahante et al, 2003; Lin et al, 2003; Abbott et al, 2005). Knocking down of hbl-1 by RNAi in lin-66 (ku423) animals resulted in an alae formation phenotype that reflected a mutual suppression of mutating the two genes, suggesting that lin-66 is unlikely to act upstream of hbl-1 (Table I).

lin-46 has also been indicated to have a role antagonistic to lin-28 in the L2 seam cell program (Pepper et al, 2004). We thus constructed a lin-66 (ku433); lin-46 (ma164 lf) mutant and found that the lin-46 allele also significantly enhanced the alae formation phenotype (Table I), suggesting that the two genes may act in parallel to regulate the L2 program.

These genetic analysis led to a model in which lin-66 negatively regulates lin-28 activity to specify the L2 seam cell program, whereas lin-14 and hbl-1 act in parallel or upstream of lin-66 and lin-28 in regulating the L1/L2/L3 programs (Figure 3).

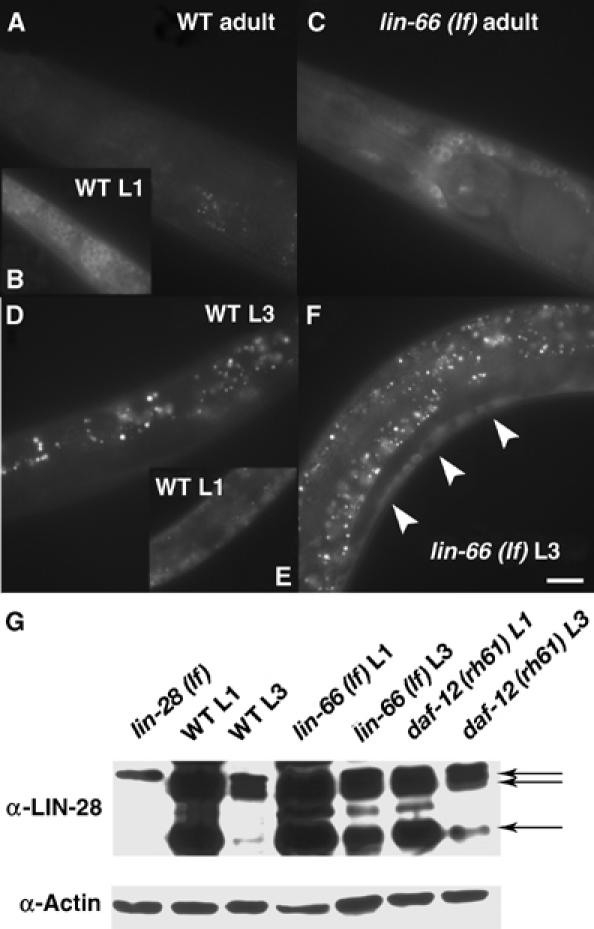

lin-66 (lf) causes an increase of LIN-28 protein level

To determine if lin-66 regulates lin-28 activity by regulating the expression of LIN-28, we examined the expression of a functional lin-28∷GFP reporter transgene (Moss et al, 1997) in the lin-66 (lf) background. This transgene, with the GFP sequence inserted at the C-terminal end of the ORF, contains both the 5′ promoter sequence and the 3′UTR of lin-28 and could rescue the phenotype of lin-28 (lf) (Moss et al, 1997). In a WT background, the expression of this lin-28∷GFP reporter was never observed at the adult stage (n=30; Figure 4A). However, the expression is prominent in adult lin-66 (ku423) mutants (100%, n=30) (Figure 4B). Similar result is obtained from the analysis of the expression in vulval cells at the L3 stage (WT, 14%, n=14; lin-66 (ku423 mutant, 92%, n=24) (Figure 4D and F). This result indicates that lin-66 represses the expression of LIN-28 in late larval and adult stages. To confirm this and quantify the result, we examined the levels of the endogenous LIN-28 protein in lin-66 (lf) and lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) double mutants by immunoblot analysis using an anti-LIN-28 antibody (gift from E Moss) (Seggerson et al, 2002). In WT, LIN-28 was abundant at L1, but its level at L3 was about 20-fold lower than that at L1 (data not shown). Such a difference is consistent with the previous report (Seggerson et al, 2002). In comparison, in lin-66 (ku423) L3 animals, the LIN-28 protein was detected at a level that is five-fold higher than that in WT L3 animals (Figure 4G and Supplementary Figure S3). In addition, the level of LIN-28 at L1 was also detected to be two-fold higher than that in WT. The increase is more prominent than that observed in daf-12 (rh61) mutants (three-fold), consistent with a stronger seam cell differentiation mutant phenotype of lin-66 (lf). However, in the alg-1 (gk214) single mutant, the LIN-28 protein level at L3 was not significantly higher than that of WT (about 1.5-fold change) (Supplementary Figure S3). This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that alg-1 plays a role in regulating another factor, likely hbl-1, for its role in L2/L3 fate specification (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

lin-66 represses LIN-28 protein levels in late larval and adult stages. (A–F) Fluorescence images of animals of the genotype and stage as indicated. The fluorescence indicates the expression of an integrated lin-28∷GFP transgene (Moss et al, 1997). In L3 animals, strong expression is seen in Pn.p cell derivatives (cells above the white line) only in lin-66 (lf) mutants. In adults, the GFP expression is essentially undetectable in WT but still seen in many neurons in the mutant. Bar, ∼50 μm. (G) Western blot analysis of endogenous LIN-28 protein using an anti-LIN-28 antibody. Arrows indicate three LIN-28 protein bands determined in a previous study (Seggerson et al, 2002). A lighter exposure of the gel is shown in Supplementary Figure S3.

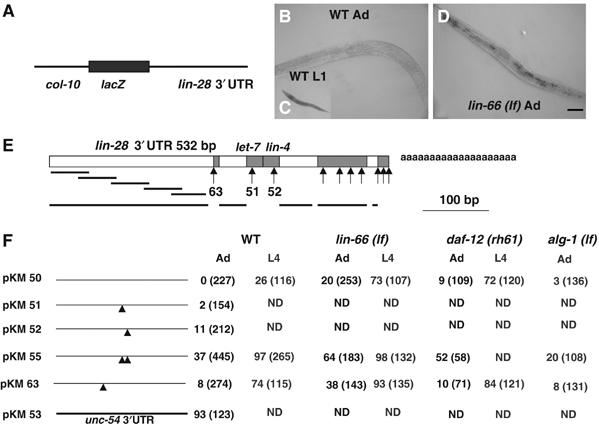

lin-66 and daf-12 may regulate lin-28 expression through its 3′UTR

To learn at what level lin-66 regulates lin-28 expression, we made transgenic worms that contain a col-10 promoter (pcol-10)∷lacZ∷lin-28 3′UTR reporter construct (Figure 5A). The col-10 promoter drives expression in hypodermal cell lineages (Wightman et al, 1993). In a WT background, prominent expression of lacZ from this reporter was observed in nearly 100% of the L1 larvae; however, no expression was detected in any adults (n>200) (Figure 5B and C), and weak expression was detected in 26% of L4 larvae (n=116). When a unc-54 3′UTR was used instead of the lin-28 3′UTR in a control construct, lacZ expression was detected in 93% of the adult animals (n=123). These results are consistent with the previous proposal that lin-28 expression is regulated post-transcriptionally through its 3′UTR (Moss et al, 1997). After crossing the same pcol-10∷lac-Z∷lin-28 3′UTR transgene into lin-66 (ku423) mutants, prominent expression of lacZ could clearly be detected in 20% of adult animals and 73% of the L4 animals (Figure 5D and F). Significant increase of the expression of the transgene was also observed in daf-12 (rh61) mutants (Figure 5F). These results suggest that lin-66 and daf-12 may regulate lin-28 expression through its 3′UTR.

Figure 5.

lin-66 regulates LIN-28 expression through the 3′UTR region of lin-28. (A) Schematic illustration of the pcol-10∷lacZ∷lin-28 3′UTR construct. (B–D) Photos showing LacZ staining of animals expressing the reporter construct (pKM50). The expression of the reporter construct is observable in the lin-66 (ku423) adult animal (D) but not in WT (B). The reporter construct is robustly expressed in WT L1 larvae (C). Bar, ∼50 μm. (E) Schematic illustration of the 3′UTR region of lin-28. Gray filled boxes indicate areas conserved between C. elegans and C. brigssae. The let-7- and lin-4-binding sites are indicated. Arrows indicate substitution or small deletion mutations made in the area, whereas bars indicate deletion mutations. The numbers indicate the plasmid shown in (F). The data for those arrows and bars without numbers are not shown, as these mutations either did not change the expression of the reporter or did not significantly change the response of the expression to lin-66, daf-12 or miRNA regulations. pKM50 is the intact 3′UTR of lin-28. pKM51 and pKM52 have a three nucleotide deletion in the let-7 (ctc) and lin-4-binding site (ggg), respectively. pKM55 has deletions of both the let-7- and lin-4-binding sites. pKM63 has a four nucleotide substitution (caaa to accc) in the indicated conserved region. (F) Percent of animals that displayed the lacZ expression of indicated construct in at least some of the hypodermal cells in various mutant backgrounds in the L4 and adult stage. Number of animals counted is indicated. Nearly 100% lacZ expression was observed in L1 animals carrying each construct and in each mutant background (data not shown).

lin-66-mediated repression is likely independent of miRNA- and daf-12-response elements in the lin-28 3′UTR

Previous work has determined that the lin-28 3′UTR mediates regulation of LIN-28 expression by miRNA and daf-12 (Moss et al, 1997; Seggerson et al, 2002). Although the daf-12-response element had not been identified, a single conserved binding site for lin-4 miRNA and a single conserved binding site for let-7 family miRNAs were identified (Figure 5E) (Moss et al, 1997; Reinhart et al, 2000). Regions conserved between C. elegans and another nematode species (C. briggsae) were also recognized (Figure 5E). To identify the lin-66-response element(s) and analyze its relationship with miRNA and daf-12 regulation, we made a number of mutations in the lin-28 3′UTR of the pcol-10∷lacZ∷lin-28 3′UTR reporter gene and analyzed the expression of these constructs at L1, L4 and adult stages (Figure 5F). First, when we introduced a mutation in the lin-4 or let-7-like miRNA binding sites, a moderate increase of lacZ expression in adult animals was detected. Mutating both the lin-4 and let-7-like miRNA-binding sites causes significantly enhanced lacZ expression, suggesting that these two sites may be responsive to a synergistic negative regulation (Bartel, 2004). However, the expression from the same transgene carrying mutations that disrupted either miRNA-binding site is further increased in the lin-66 (ku423) or daf-12 (rh61) mutant adults (Figure 5F). This result is consistent with the hypothesis that the regulation through these two miRNA sites may be independent of the regulation by lin-66 and daf-12. Additionally, the expression of the transgene with both miRNA-binding sites disrupted might be near saturation in WT L4 larvae, as a significant increase in expression in the lin-66 (lf) background was not observed.

When another conserved region upstream of the miRNA-binding sites was mutated (four nucleotide substitutions; pKM63), the lacZ expression was also significantly increased in WT L4 larvae and adults (Figure 5F). The lin-66 (lf) mutation, but not the daf-12 (rh61) mutation, significantly enhanced the expression of lacZ (Figure 5F), suggesting that the region mutated in pKM63 may be involved in daf-12-mediated regulation that is likely independent of the lin-66 regulation.

We have carried out a series of deletion analyses on the lin-28 3′UTR in the reporter construct, but failed to identify a specific DNA region that clearly displays the property of a potential lin-66 response element (data not shown). Gel-shift assays were also unable to detect the binding of LIN-66 on the lin-28 3′UTR, suggesting the possibility that other factors may mediate the interaction between LIN-66 and the 3′UTR of lin-28. Therefore, the proposed lin-66 regulation on the lin-28 3′UTR remains to be supported by further biochemical analysis.

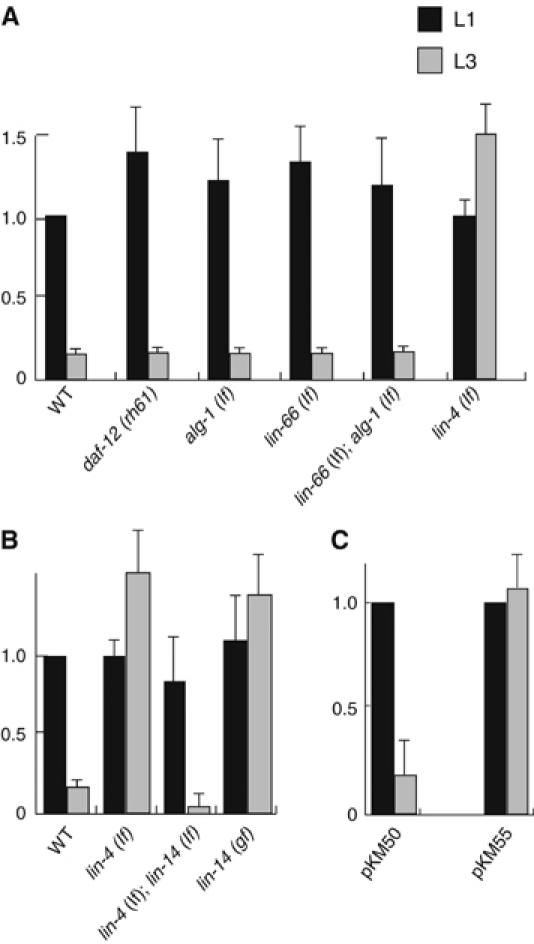

lin-28 mRNA level is significantly changed by altering lin-14 or miRNA function, but not lin-66 or daf-12 function

As previous work and the above data indicate that lin-66, daf-12 (rh61) and miRNAs repress lin-28 expression through its 3′UTR, the repression may be caused by either RNA degradation or translational inhibition. To distinguish these two possibilities, we performed quantitative RT–PCR to compare the mRNA level in WT and mutant larvae. In WT, the level of lin-28 mRNA was observed to decrease approximately seven-fold from the early L1 stage to the L3 stage (Figure 6A). This change is consistent with the result in a recent report (Bagga et al, 2005). In lin-66 (ku423) and daf-12 (rh61) animals, the levels of lin-28 mRNA at early L1 and L3 stage were similar to that in WT worms (Figure 6A). These data indicate that lin-66 and daf-12 do not regulate lin-28 expression through RNA degradation, implying possible roles for these genes in protein translation, which is consistent with previously proposed translational inhibition of lin-28 at late larval stages in WT animals (Moss et al, 1997).

Figure 6.

mRNA levels of lin-28. (A–C) lin-28 mRNA levels in various strains indicated were determined by real-time RT–PCR. The alleles used are listed in Materials and methods. pKM50 and pKM55 are reporter constructs depicted in Figure 5, and they were integrated into the genome before the PCR analysis. Error bars indicate the s.d..

As was observed in a previous study (Bagga et al, 2005), the lin-28 mRNA level was drastically increased in lin-4 (lf) mutants (Figure 6A), consistent with the idea that lin-4 miRNA represses lin-28 expression by promoting RNA degradation. However, this increase could be due to an indirect regulation mediated by lin-14/transcription factor, as lin-4 has a prominent role in repressing the expression of lin-14, which has a positive effect on lin-28 expression (Seggerson et al, 2002). We addressed this question by quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis. We show that the lin-28 mRNA level is at a very low level in L3 larvae of lin-4 (lf); lin-14 (lf) double mutants but at a high level in L3 larvae of lin-14 (gf) similar to that of the lin-4 (lf) mutants (Figure 6B). These results suggest that the majority of the increase in lin-28 mRNA level in lin-4 (lf) was likely due to an increase in the level of the LIN-14 transcription factor, which is consistent with several observations in previous studies and this study (see Discussion).

To investigate whether RNA degradation is still a mechanism involved in regulating lin-28 expression by miRNA, we performed qPCR analysis of mRNA transcribed from the pcol-10∷lacZ∷lin-28 3′UTR transgene that had deleted of both lin-4 miRNA and let-7 family miRNA-binding sites (Figure 5). We observed that in L3 animals, the level of mRNA transcribed from the reporter gene containing the deletion drastically increased, compared to that transcribed from the reporter gene without the deletion. This result supports the notion that RNA degradation is an important mechanism by which lin-4 and let-7-family miRNAs repress gene expression (Bagga et al, 2005).

These qPCR results, along with the results from genetic and reporter-gene analyses, indicate that lin-66, daf-12, miRNAs and lin-14 mediate four independent mechanisms to regulate the expression of lin-28.

Discussion

lin-66 likely acts in parallel to daf-12 and miRNAs to inhibit lin-28 expression

lin-28 functions to specify the L2 developmental programs and the downregulation of its expression is required for animals to exit the L2 programs in late larval stages (Moss et al, 1997). The similar retarded mutant phenotypes associated with lin-66 and daf-12, especially the robust L2 seam cell reiteration phenotype of lin-66 (lf); daf-12 (lf) double mutants (Table II), clearly indicate that the mechanisms mediated by these two proteins play critical roles in repressing lin-28 expression in late larval stages. LIN-66 and DAF-12 proteins appear to act independently on the lin-28 3′UTR to repress and promote translation, respectively.

Previous work has indicated that lin-28 is one of the targets of lin-4 miRNA, and a potential lin-4-binding site on the lin-28 3′UTR was also identified (Moss et al, 1997). A deletion of the lin-4-binding site in the reporter construct caused only a small increase in expression, but this deletion significantly enhanced the phenotype of the deletion of the let-7-like-binding site (Figure 5), suggesting that multiple miRNAs may have partially redundant activities in repressing lin-28 expression (Figure 3). The repression mediated by miRNAs appears also to be independent of lin-66 and daf-12 as the expression of a pcol-10∷lacZ∷lin-28 3′UTR reporter with both the miRNA-binding sites mutated is still subject to regulation by lin-66 and daf-12. Furthermore, miRNAs, but not lin-66 and daf-12, appear to be involved in regulating the lin-28 mRNA level. Consistent with the suggestion that lin-66 may not be involved in general miRNA maturation or function, the levels of lin-4 and let-7 family miRNAs were shown to be normal in a lin-66 mutant by Northern analysis (Supplementary Figure S4), and miRNA was not found to be associated with LIN-66∷GFP protein in a co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiment using an anti-GFP antibody (data not shown).

Using biochemical assays, we failed to see a direct interaction between LIN-66 and the lin-28 3′UTR (data not shown), leaving a good possibility that the LIN-66 interaction with the lin-28 3′UTR is indirect. Our co-IP test has so far failed to identify proteins that are associated with LIN-66 (data not shown).

It is interesting to learn that multiple mechanisms are critically involved in regulating the expression of lin-28 in late larval stages (Figure 3). Disrupting or disturbing any of these mechanisms would cause a significant increase in the LIN-28 protein level and retarded phenotypes. This is in contrast to spatial regulation of expression of other developmental regulators where multiple pathways redundantly repress their transcription in certain tissues (Cui et al, 2006).

Roles of lin-4 miRNA and LIN-14 transcription factor in lin-28 expression

lin-28 mRNA level was shown in a recent report as well as in this study to be significantly increased in later larval stage in lin-4 (lf) mutants (Bagga et al, 2005) (Figure 6A). However, we only observed a minor effect resulting from deleting the lin-4-binding site in the lin-28 3′UTR. A likely scenario is that the major effect on lin-28 expression seen in lin-4 (lf) is due to an indirect effect mediated by lin-14 on lin-28 transcription. lin-14 is a major target of lin-4 miRNA and lin-4 (lf) causes severe derepression of lin-14 expression (Wightman et al, 1993). It has been shown that in a lin-4 (lf) mutant, lin-28 protein level decreases if lin-14 activity is reduced or eliminated, suggesting that lin-14 promotes lin-28 expression (Moss et al, 1997; Seggerson et al, 2002). Finally, we have shown in this study that lin-28 mRNA levels are low in lin-4 (lf); lin-14 (lf) double mutants but high in a lin-14 (gf) mutant (Figure 6B), suggesting that the increase of lin-28 mRNA levels in the lin-4 (lf) single mutant depends on lin-14(+). However, we have not demonstrated that lin-28 is a direct target of the LIN-14 transcription factor. Taken together, these data suggest that lin-4 miRNA acts redundantly with let-7 family miRNAs to promote lin-28 mRNA degradation, whereas lin-14 may upregulate lin-28 mRNA either by transcription activation or through another indirect mechanism.

Function of daf-12 on lin-28 expression

The fact that both daf-12 (rh61) and a daf-12 (null) allele significantly enhanced the retarded phenotype of lin-66 (lf) suggests that the daf-12 (rh61) allele expresses a protein with a role that is opposite to that of DAF-12(+), which likely represses lin-28 expression. daf-12 encodes a nuclear receptor. It has been proposed that DAF-12 changes from a transcriptional repressor to an activator upon binding to a ligand (Antebi, 2006). The rh61 mutant allele produces a truncated protein that is expected to lose the ability to bind to a ligand (Antebi et al, 2000), and thus may constitutively repress transcription, which likely accounts for the mutant effect. As daf-12 (rh61) causes the upregulation of lin-28 expression and acts on the lin-28 3′UTR (Seggerson et al, 2002) (this study), this regulation could be indirect; daf-12 (rh61) may repress the transcription of a factor involved in interacting with the lin-28 3′UTR to repress its expression. Mutational analysis of a reporter construct and qPCR analysis suggest that daf-12 (rh61) acts on a site that is distinct from miRNA-binding sites and it may not act to degrade lin-28 mRNA.

Functional relationships of lin-66 with alg-1 and hbl-1

We show in this paper that lin-66 (lf) and alg-1 (lf) double mutants display an L2 reiteration phenotype that is much stronger than that of either single mutation (Figures 1 and 2), suggesting that these two genes may have parallel activities in regulating the L2-to-L3 transition. alg-1 and alg-2 encode homologues of argonaute proteins and have been shown to be involved specifically in the maturation and function of miRNA (Grishok et al, 2001). It is thus possible that the alg-1 (lf) mutant effect reflects miRNA regulation on lin-28. However, Western blot analysis did not reveal a significant increase in the LIN-28 protein level in lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) double mutants (Supplementary Figure S3). Furthermore, the expression of the pcol-10∷lacZ∷lin-28 3′UTR reporter construct did not display a prominent increase in alg-1 (lf) mutants (Figure 5F).

An alternative explanation is that alg-1 plays a more prominent role in the L2/L3 transition by regulating another factor, likely the hbl-1 gene, which encodes a hunchback-like transcription factor and was shown to regulate the L2/L3 and L4/adult transitions (Fay et al, 1999; Abrahante et al, 2003; Lin et al, 2003). Recently, it has been shown that three let-7 family miRNAs (mir-48, mir-84 and mir-241) redundantly regulate the L2-to-L3 transition mainly by repressing hbl-1 expression (Abbott et al, 2005). Therefore, the L2 reiteration phenotype of alg-1 (lf) is likely due, to a large extent, to the disruption of the regulation of hbl-1 by these miRNAs. However, as our deletion analysis suggests that let-7 family miRNAs also work together with lin-4 miRNA to regulate lin-28 expression, alg-1 may also play a role in lin-28 regulation.

lin-28 regulates the competence of VPC cell division timing

Euling and Ambros (1996) have previously shown that in WT, the VPC cell cycle contains a long G1 phase from mid-L1 to the end of the L2 stage. The first round of cell divisions of VPCs is completed at the mid-L3 stage (Figure 3G). In a lin-28 mutant, the G1 phase of the VPCs is shortened and the first round of VPC divisions occurs at the mid-L2 stage (Euling and Ambros, 1996). We show in this paper that in lin-66 (lf) and lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) double mutants, the first round of VPC divisions is delayed, suggesting a longer than normal G1 phase for the VPCs in these mutants.

It is worthy to mention that the delay in the first round of VPC division observed in lin-66 (lf) and lin-66 (lf); alg-1 (lf) was not previously observed in known retarded heterochronic mutants. In particular, the first round of VPC division occurred at a similar time in lin-4 (lf) and lin-14 (gf) mutants as that in WT (Chalfie et al, 1981; Euling and Ambros, 1996) (Figure 1H). In these animals, the second and third rounds of vulval cell divisions are randomized and these cells cannot respond properly to inductive signalling (Chalfie et al, 1981; Euling and Ambros, 1996). In comparison, vulval cell divisions in lin-66 (lf) mutants are delayed but still coordinated, often capable of generating a vulva in the adult stage. We speculate that the difference between lin-66 (lf)/alg-1 (lf) and lin-4 (lf)/lin-14 (gf) mutants reflects the difference between VPC programs in L1 and L2. In a lin-66 (lf) mutant, the high level of LIN-28 causes the L2 stage, at which VPCs are in G1 phase, to repeat once and VPC divisions to be delayed by one stage. As EGFR-mediated inductive signalling occurs at the L2 and L3 stages, vulval cells in lin-66 (lf) may still be able to respond to the signalling. On the other hand, both lin-4 (lf) and lin-14 (gf) cause hyperactive LIN-14 and reiteration of the L1 program in hypodermal cells. VPCs in the L1 stage may not be competent to properly respond to the inductive signal that only affects the second and third rounds of vulval divisions (Sternberg and Horvitz, 1986).

Materials and methods

General method and strain

Mutagenesis and genetic crosses were performed as described by Wood (1988). The following strains were used: WT C. elegans variety Bristol strain (N2), lin-31 (n301); eff-1 (hy21), let-7 (mn112); unc-3 (e151), lin-4 (e912), lin-14 (n179ts), lin-14 (ma135), lin-14 (n355 gf), lin-28 (n719), llin-29 (n333), lin-41 (ma104), lin-42 (n1089), lin-46 (ma164), daf-12 (rh61), daf-12 (rh61rh411), daf-12 (m20), hbl-1 (ve12), alg-1 (ok214), alg-2 (ok304), egl-17∷GFP (ayIs4), lin-28∷GFP (VT808), SCM∷GFP (QwIS79).

Mutagenesis, mapping and positional cloning

The screen for suppressors of lin-31 (n301); eff-1 (hy21) animals has been previously described (Morita et al, 2005). SNP mapping (Wicks et al, 2001) was performed to determine chromosomal locations of ku423 and ku424. The gene was placed between cosmid F52H3 and F37H8. Microinjection transformation was performed to identify DNA sequences that were able to rescue the mutant phenotype. The DNA lesions were determined by directly sequencing genomic DNA.

Phenotypic analysis

Alae formation and VPC division timing were analyzed under Nomarski optics as described previously (Euling and Ambros, 1996). Cells positive for the seam cell marker (scm-1∷GFP) were counted under Nomarski and fluorescence microscopy. The stages of development were determined by examining the body size, molting state, size and shape of the gonad arms, and the stage of germline development.

Western analysis

Lysates from synchronized worms (hatched L1 and L3) were prepared as described previously (Seggerson et al, 2002).

Construction and expression analysis of the pcol-10∷lacZ∷lin-28 3′UTR transgene

A pcol-10-lac-Z-lin-28 3′UTR construct (pKM50) was generated as follows. The lin-28 3′UTR from a lin-28 cDNA clone, yk117g6, was amplified by PCR and subcloned into the SpeI and ApaI sites of the pPD95.11 vector. The col-10 promoter was PCR amplified from genomic DNA and then subcloned into the PstI and BamHI sites of the resulting plasmid to create pKM50. The deletion or substitution mutations within the lin-28 3′UTR region were introduced to the reporter construct using the Stratagene QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit and confirmed by direct sequencing. These constructs were injected at 2 ng/μl with the marker Myo-3∷GFP into WT hermaphrodites. At least three independent lines were generated for each construct. These constructs were crossed into mutants to examine expression in various genetic backgrounds. Animals with green fluorescence were selected for lacZ staining following a standard protocol.

Real-time RT–PCR

Synchronized L1 and L3 worms were prepared using a standard alkaline hypochlorite method and by selecting the L3 animals under a dissecting scope (∼500 worms for each sample). mRNA was prepared using Trizol (Invitrogen) and the reverse transcription reaction was performed using the SuperScript III Kit (Invitrogen). PCR reactions were performed using the SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (SIGMA) and the Rotor-Gene RG-3000 system (CORBETT RESEARCH). eft-2 was used as an internal control (Bagga et al, 2005).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Figure S4

Acknowledgments

We thank the C. elegans Genetics Center for strains, Eric Moss for the lin-28 antibody and lin-28∷GFP strain, and Y Kohara for clones. We thank Eric Moss, Victor Ambros and Frank Slack for helpful discussions and suggestions, and J Blanchette, M Cui, L Ding, M Tucker, A Sewell and members of our laboratory for their comments and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM47869) and by HHMI, of which KM is an associate and MH is an investigator.

References

- Abbott AL, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Miska EA, Lau NC, Bartel DP, Horvitz HR, Ambros V (2005) The let-7 microRNA family members mir-48, mir-84, and mir-241 function together to regulate developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell 9: 403–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahante JE, Daul AL, Li M, Volk ML, Tennessen JM, Miller EA, Rougvie AE (2003) The Caenorhabditis elegans hunchback-like gene lin-57/hbl-1 controls developmental time and is regulated by microRNAs. Dev Cell 4: 625–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V (1989) A hierarchy of regulatory genes controls a larva-to-adult developmental switch in C. elegans. Cell 57: 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V (1999) Cell cycle-dependent sequencing of cell fate decisions in Caenorhabditis elegans vulva precursor cells. Development 126: 1947–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431: 350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V, Horvitz HR (1984) Heterochronic mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 226: 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antebi A (2006) Nuclear hormone receptors in C. elegans (January 03, 2006). WormBook, ed, http://www.wormbook.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antebi A, Culotti JG, Hedgecock EM (1998) daf-12 regulates developmental age and the dauer alternative in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 125: 1191–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antebi A, Yeh WH, Tait D, Hedgecock EM, Riddle DL (2000) daf-12 encodes a nuclear receptor that regulates the dauer diapause and developmental age in C. elegans. Genes Dev 14: 1512–1527 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasu P, Wightman B, Ruvkun G (1991) Temporal regulation of lin-14 by the antagonistic action of two other heterochronic genes, lin-4 and lin-28. Genes Dev 5: 1825–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagga S, Bracht J, Hunter S, Massirer K, Holtz J, Eachus R, Pasquinelli AE (2005) Regulation by let-7 and lin-4 miRNAs results in target mRNA degradation. Cell 122: 553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdine RD, Branda CS, Stern MJ (1998) EGL-17(FGF) expression coordinates the attraction of the migrating sex myoblasts with vulval induction in C. elegans. Development 125: 1083–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Horvitz HR, Sulston JE (1981) Mutations that lead to reiterations in the cell lineages of C. elegans. Cell 24: 59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Chen J, Myers TR, Hwang BJ, Sternberg PW, Greenwald I, Han M (2006) SynMuv genes redundantly inhibit lin-3/EGF expression to prevent inappropriate vulval induction in C. elegans. Dev Cell 10: 667–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Spencer A, Morita K, Han M (2005) The developmental timing regulator AIN-1 interacts with miRISCs and may target the argonaute protein ALG-1 to cytoplasmic P bodies in C. elegans. Mol Cell 19: 437–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euling S, Ambros V (1996) Heterochronic genes control cell cycle progress and developmental competence of C. elegans vulva precursor cells. Cell 84: 667–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay DS, Stanley HM, Han M, Wood WB (1999) A Caenorhabditis elegans homologue of hunchback is required for late stages of development but not early embryonic patterning. Dev Biol 205: 240–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishok A, Pasquinelli AE, Conte D, Li N, Parrish S, Ha I, Baillie DL, Fire A, Ruvkun G, Mello CC (2001) Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell 106: 23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans H, Johnson T, Reinert KL, Gerstein M, Slack FJ (2005) The temporal patterning microRNA let-7 regulates several transcription factors at the larval to adult transition in C. elegans. Dev Cell 8: 321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh K, Rothman JH (2001) ELT-5 and ELT-6 are required continuously to regulate epidermal seam cell differentiation and cell fusion in C. elegans. Development 128: 2867–2880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75: 843–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SY, Johnson SM, Abraham M, Vella MC, Pasquinelli A, Gamberi C, Gottlieb E, Slack FJ (2003) The C elegans hunchback homolog, hbl-1, controls temporal patterning and is a probable microRNA target. Dev Cell 4: 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZC, Ambros V (1989) Heterochronic genes control the stage-specific initiation and expression of the dauer larva developmental program in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev 3: 2039–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K, Hirono K, Han M (2005) The Caenorhabditis elegans ect-2 RhoGEF gene regulates cytokinesis and migration of epidermal P cells. EMBO Rep 6: 1163–1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss EG, Lee RC, Ambros V (1997) The cold shock domain protein LIN-28 controls developmental timing in C. elegans and is regulated by the lin-4 RNA. Cell 88: 637–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss EG, Tang L (2003) Conservation of the heterochronic regulator Lin-28, its developmental expression and microRNA complementary sites. Dev Biol 258: 432–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli AE, Ruvkun G (2002) Control of developmental timing by microRNAs and their targets. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 18: 495–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper AS, McCane JE, Kemper K, Yeung DA, Lee RC, Ambros V, Moss EG (2004) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-46 affects developmental timing at two larval stages and encodes a relative of the scaffolding protein gephyrin. Development 131: 2049–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G (2000) The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403: 901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougvie AE (2001) Control of developmental timing in animals. Nat Rev Genet 2: 690–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougvie AE (2005) Intrinsic and extrinsic regulators of developmental timing: from miRNAs to nutritional cues. Development 132: 37837–37898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvkun G, Giusto J (1989) The Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene lin-14 encodes a nuclear protein that forms a temporal developmental switch. Nature 338: 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seggerson K, Tang L, Moss EG (2002) Two genetic circuits repress the Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene lin-28 after translation initiation. Dev Biol 243: 215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg P (2005) Vulval development. URL∷ http://www.wormbook.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sternberg PW, Horvitz HR (1986) Pattern formation during vulval development in C. elegans. Cell 44: 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR (1977) Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 56: 110–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicks SR, Yeh RT, Gish WR, Waterston RH, Plasterk RH (2001) Rapid gene mapping in Caenorhabditis elegans using a high density polymorphism map. Nat Genet 28: 160–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G (1993) Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 75: 855–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood WB (1988) The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Figure S4