Abstract

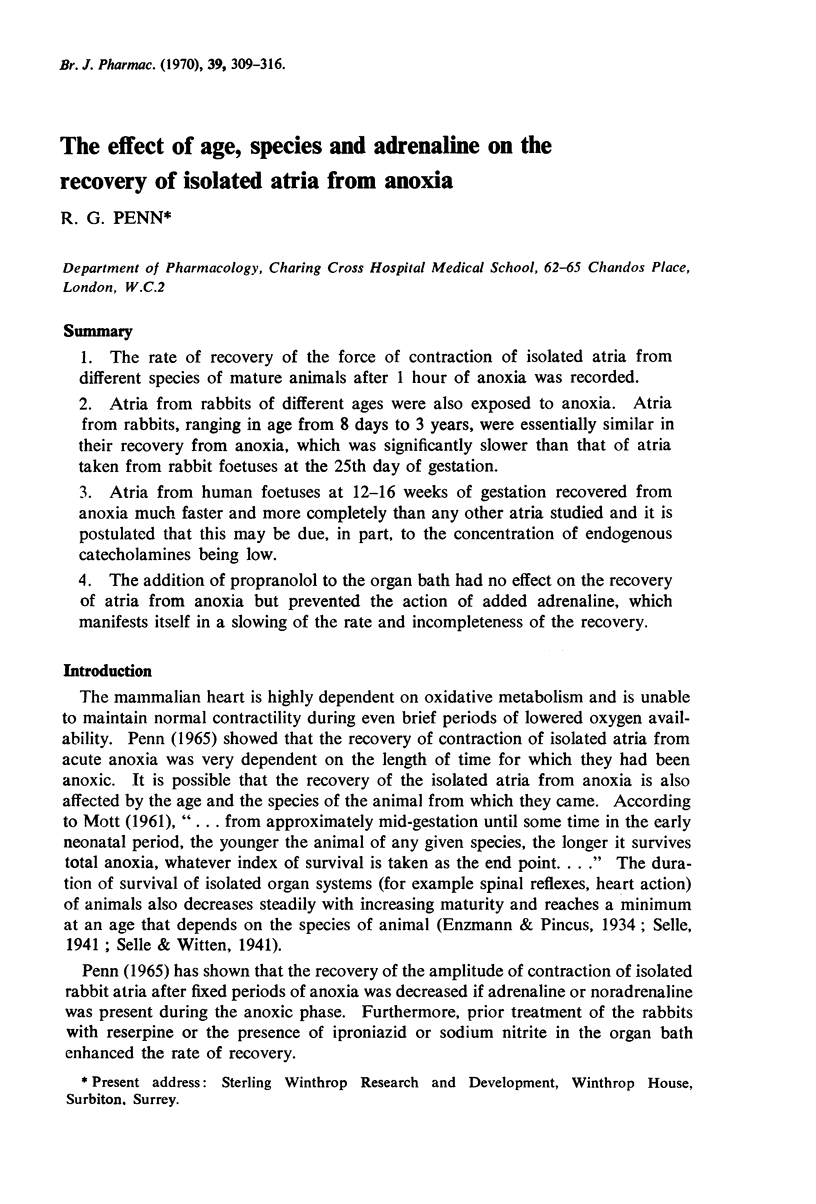

1. The rate of recovery of the force of contraction of isolated atria from different species of mature animals after 1 hour of anoxia was recorded.

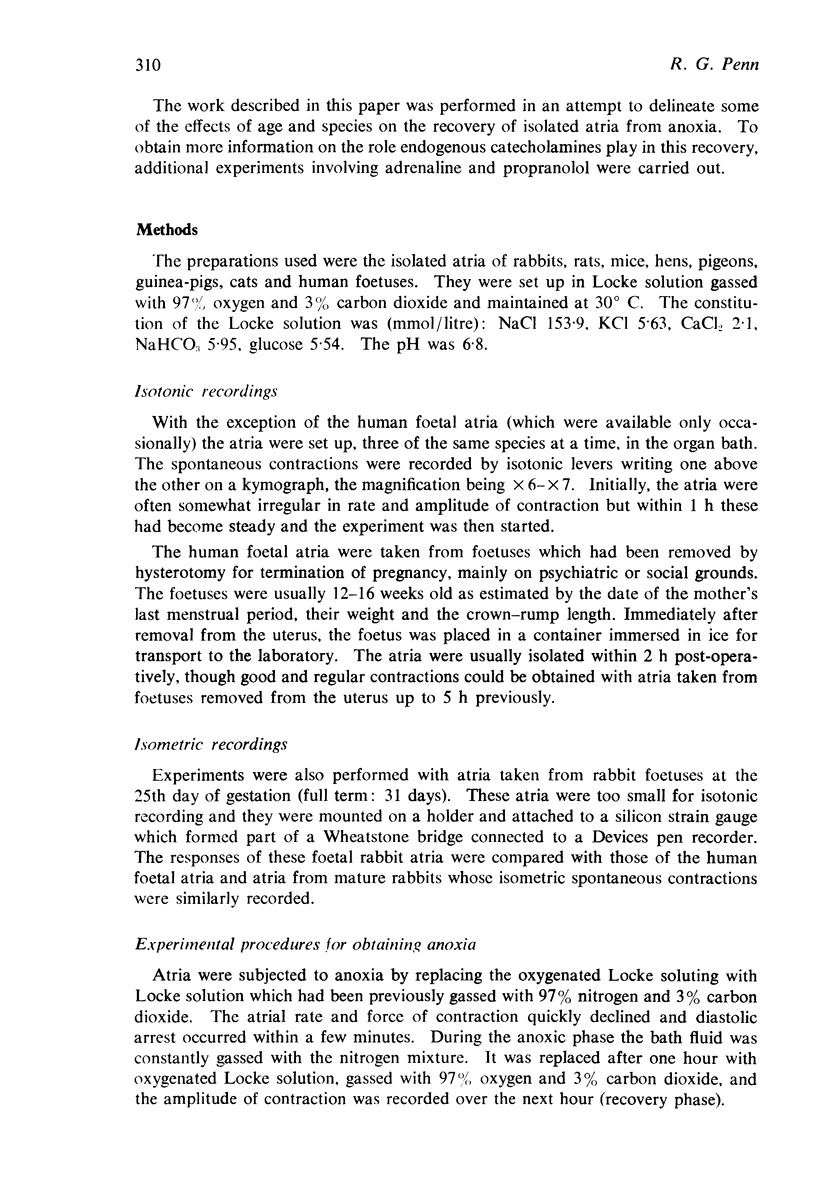

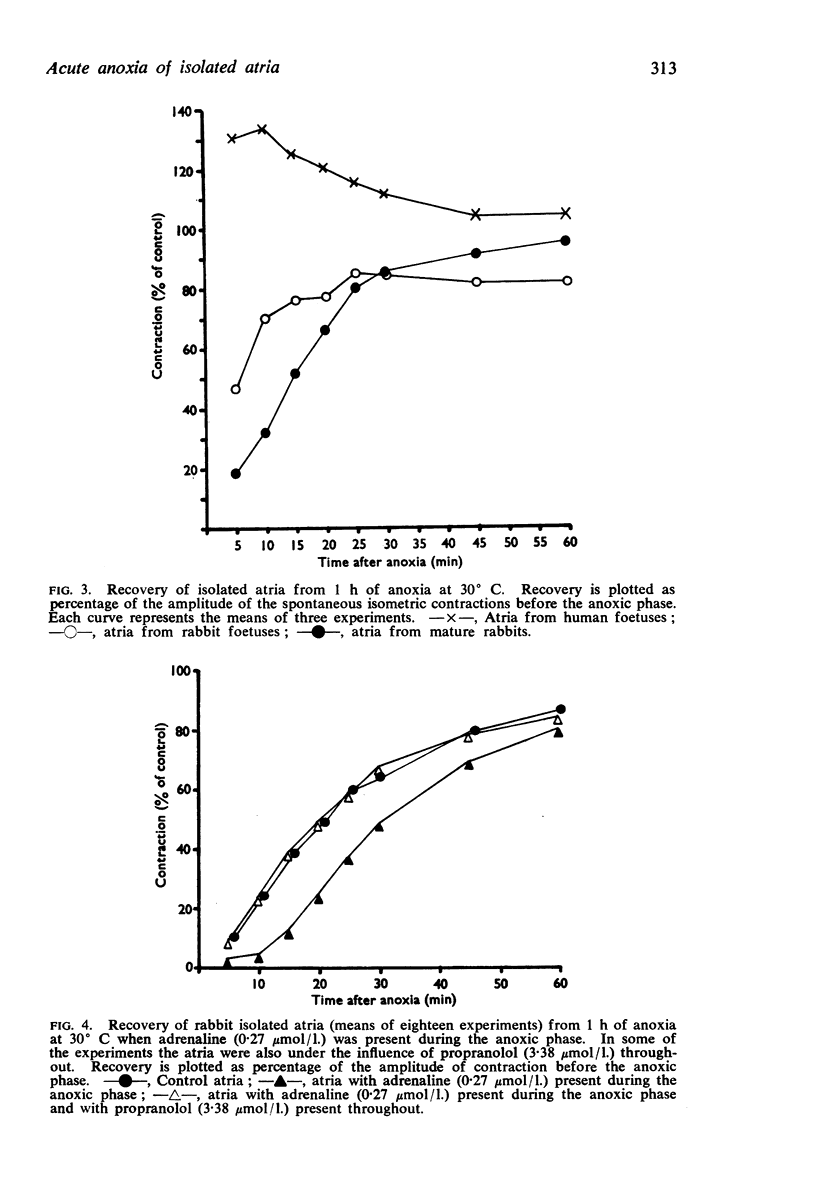

2. Atria from rabbits of different ages were also exposed to anoxia. Atria from rabbits, ranging in age from 8 days to 3 years, were essentially similar in their recovery from anoxia, which was significantly slower than that of atria taken from rabbit foetuses at the 25th day of gestation.

3. Atria from human foetuses at 12-16 weeks of gestation recovered from anoxia much faster and more completely than any other atria studied and it is postulated that this may be due, in part, to the concentration of endogenous catecholamines being low.

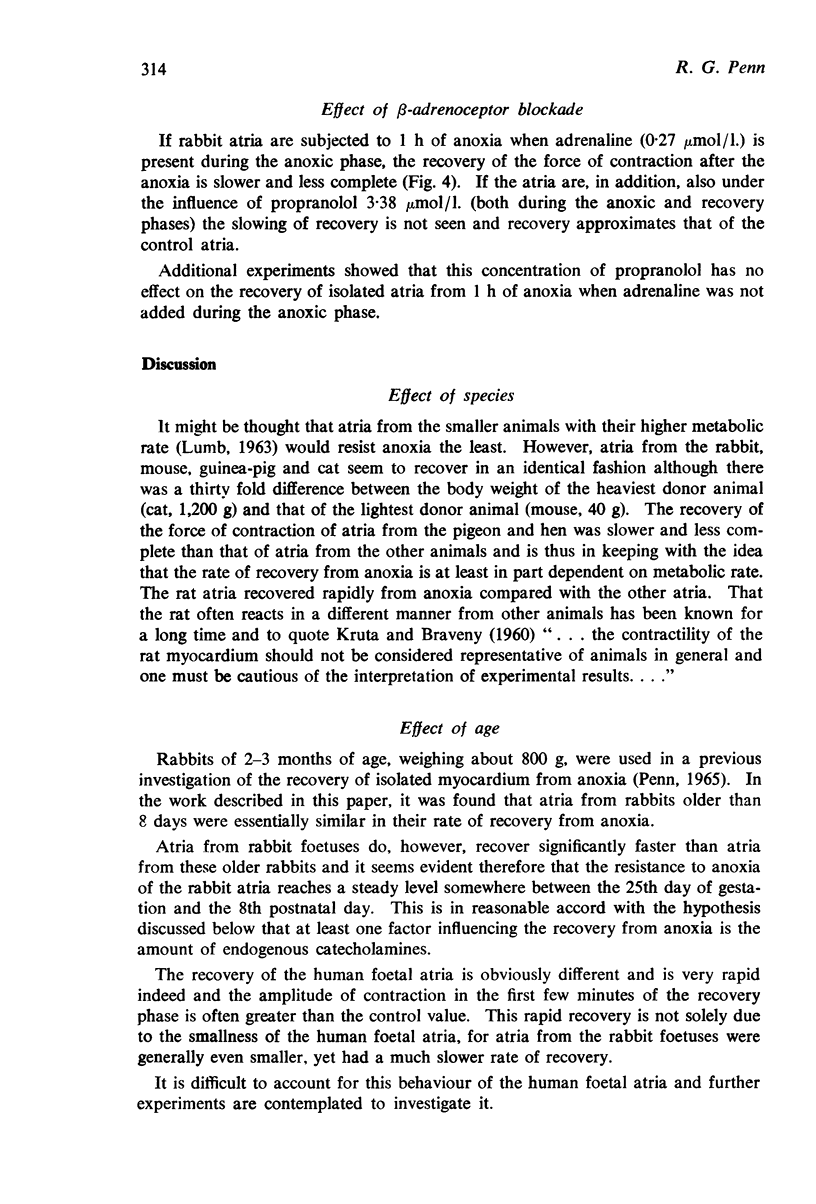

4. The addition of propranolol to the organ bath had no effect on the recovery of atria from anoxia but prevented the action of added adrenaline, which manifests itself in a slowing of the rate and incompleteness of the recovery.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BERNE R. M. Cardiac nucleotides in hypoxia: possible role in regulation of coronary blood flow. Am J Physiol. 1963 Feb;204:317–322. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1963.204.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceremuzyński L., Staszewska-Barczak J., Herbaczynska-Cedro K. Cardiac rhythm disturbances and the release of catecholamines after acute coronary occlusion in dogs. Cardiovasc Res. 1969 Apr;3(2):190–197. doi: 10.1093/cvr/3.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman W. F., Pool P. E., Jacobowitz D., Seagren S. C., Braunwald E. Sympathetic innervation of the developing rabbit heart. Biochemical and histochemical comparisons of fetal, neonatal, and adult myocardium. Circ Res. 1968 Jul;23(1):25–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.23.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRUTA V., BRAVENY M. [Physiological differences between the myocardium of the rat and certain other mammals]. J Physiol (Paris) 1960 Jan-Feb;52:137–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE W. C., MCCARTY L. P., ZODROW W. W., SHIDEMAN F. E. The cardiostimulant action of certain ganglionic stimulants on the embryonic chick heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1960 Sep;130:30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOTT J. C. The ability of young mammals to withstand total oxygen lack. Br Med Bull. 1961 May;17:144–148. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a069889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENNA M., LINARES F., CACERES L. MECHANISM FOR CARDIAC STIMULATION DURING HYPOXIA. Am J Physiol. 1965 Jun;208:1237–1242. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.208.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENN R. G. SOME FACTORS INFLUENCING THE RECOVERY OF ISOLATED MYOCARDIUM FROM ACUTE ANOXIA. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1965 Feb;24:253–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1965.tb02101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto K., Toda N. Modifications by propranolol of the response of isolated rabbit atria to endogenous and exogenous noradrenaline. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1968 Mar;32(3):539–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1968.tb00454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staszewska-Barczak J., Ceremuzynski L. The continuous estimation of catecholamine release in the early stages of myocardial infarction in the dog. Clin Sci. 1968 Jun;34(3):531–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]