Abstract

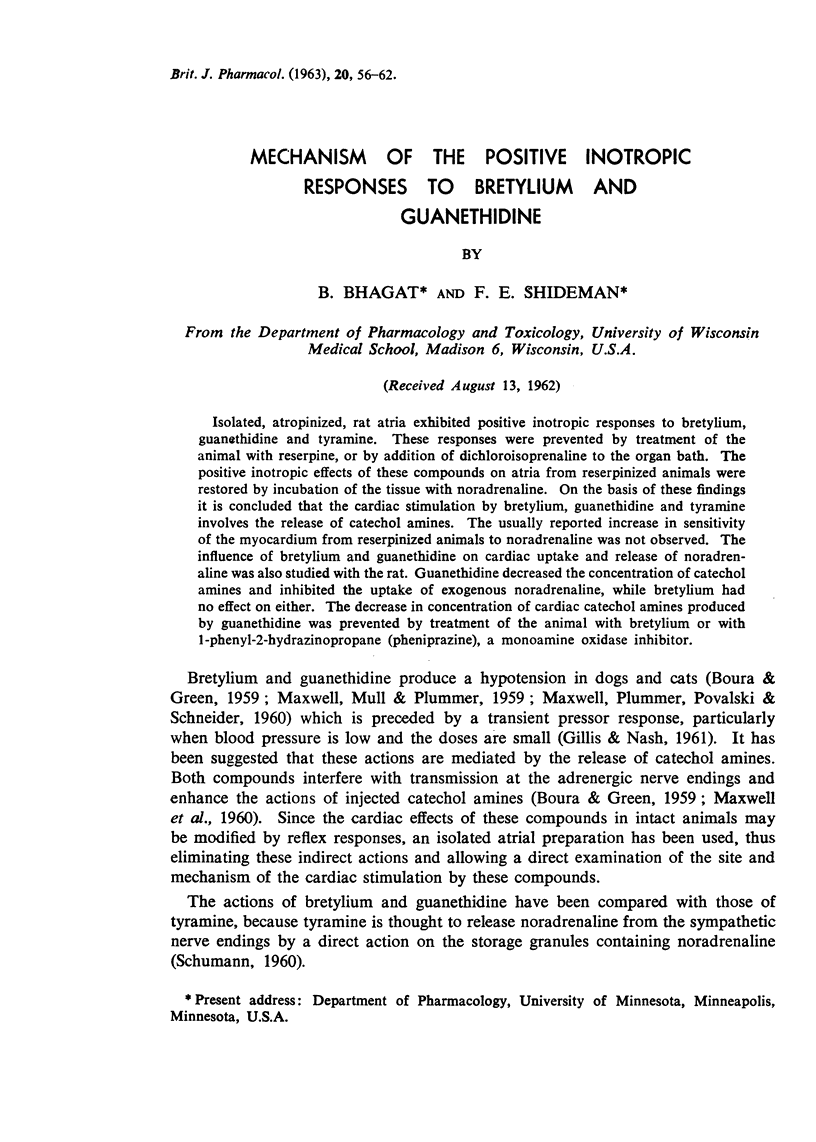

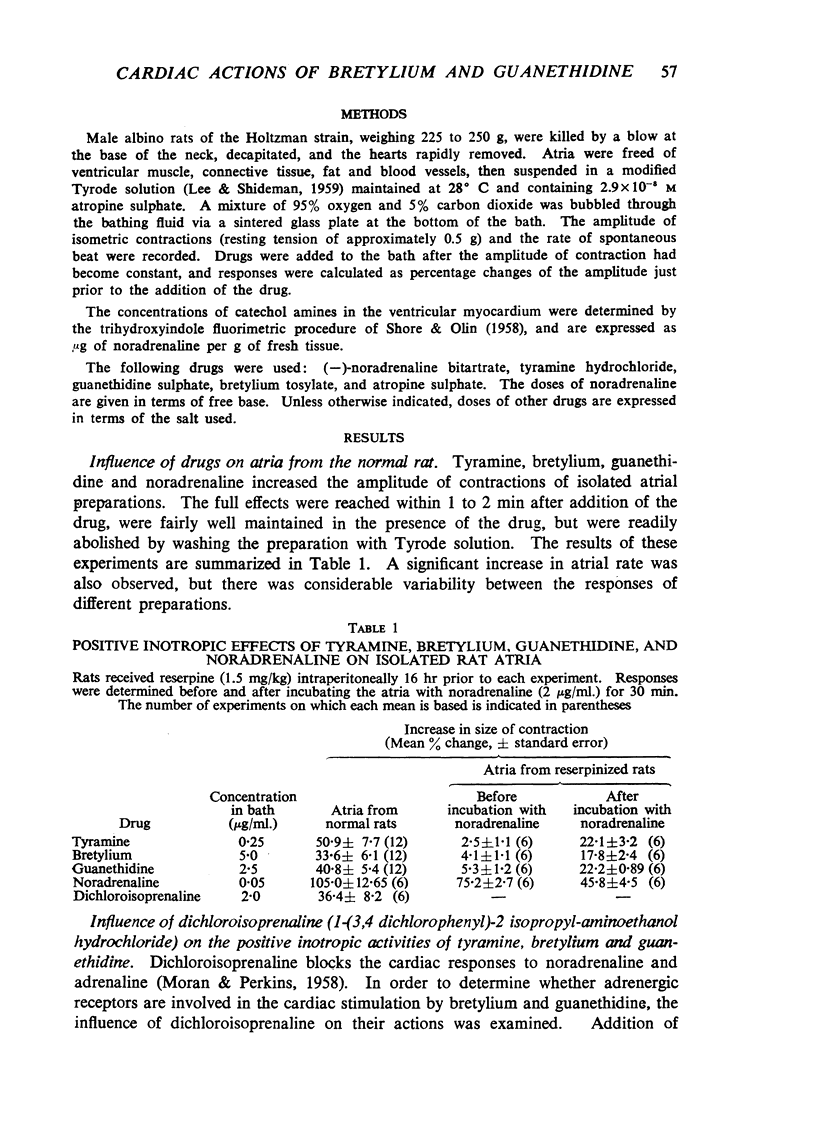

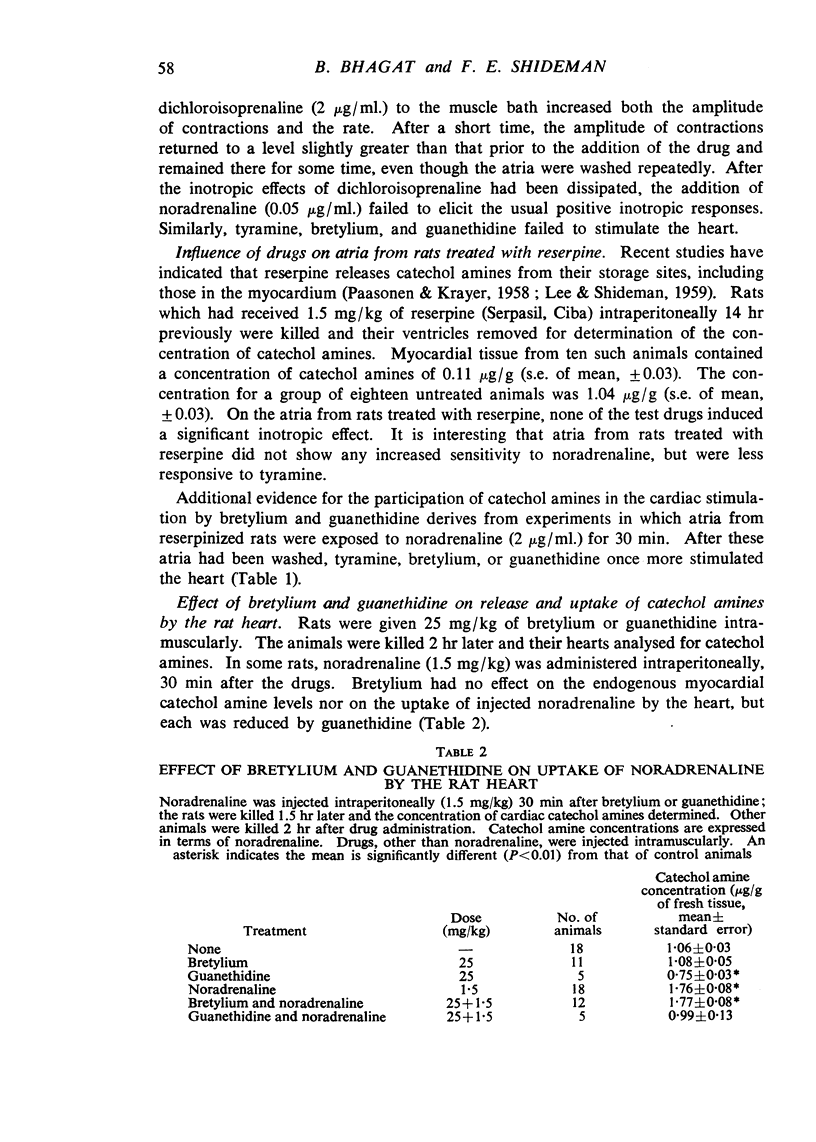

Isolated, atropinized, rat atria exhibited positive inotropic responses to bretylium, guanethidine and tyramine. These responses were prevented by treatment of the animal with reserpine, or by addition of dichloroisoprenaline to the organ bath. The positive inotropic effects of these compounds on atria from reserpinized animals were restored by incubation of the tissue with noradrenaline. On the basis of these findings it is concluded that the cardiac stimulation by bretylium, guanethidine and tyramine involves the release of catechol amines. The usually reported increase in sensitivity of the myocardium from reserpinized animals to noradrenaline was not observed. The influence of bretylium and guanethidine on cardiac uptake and release of noradrenaline was also studied with the rat. Guanethidine decreased the concentration of catechol amines and inhibited the uptake of exogenous noradrenaline, while bretylium had no effect on either. The decrease in concentration of cardiac catechol amines produced by guanethidine was prevented by treatment of the animal with bretylium or with 1-phenyl-2-hydrazinopropane (pheniprazine), a monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- AXELROD J., WEIL-MALHERBE H., TOMCHICK R. The physiological disposition of H3-epinephrine and its metabolite metanephrine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1959 Dec;127:251–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOURA A. L., GREEN A. F. The actions of bretylium: adrenergic neurone blocking and other effects. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1959 Dec;14:536–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00961.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURN J. H., RAND M. J. Noradrenaline in artery walls and its dispersal by reserpine. Br Med J. 1958 Apr 19;1(5076):903–908. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5076.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURN J. H., RAND M. J. The action of sympathomimetic amines in animals treated with reserpine. J Physiol. 1958 Dec 4;144(2):314–336. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1958.sp006104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURN J. H., RAND M. J. The cause of the supersensitivity of smooth muscle to noradrenaline after sympathetic degeneration. J Physiol. 1959 Jun 23;147(1):135–143. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bülbring E., Burn J. H. The action of tyramine and adrenaline on the denervated nictitating membrane. J Physiol. 1938 Jan 14;91(4):459–473. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1938.sp003573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASS R., SPRIGGS T. L. Tissue amine levels and sympathetic blockade after guanethidine and bretylium. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1961 Dec;17:442–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1961.tb01131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROUT J. R., CREVELING C. R., UDENFRIEND S. Norepinephrine metabolism in rat brain and heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961 Jun;132:269–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILLIS C. N., NASH C. W. The initial pressor actions of bretylium tosylate and guanethidine sulfate and their relation to release of catecholamines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961 Oct;134:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDBERG N. D., SHIDEMAN F. E. Species differences in the cardiac effects of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1962 May;136:142–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERTTING G., AXELROD J., PATRICK R. W. Actions of bretylium and guanethidine on the uptake and release of [3H]-noradrenaline. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1962 Feb;18:161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1962.tb01159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE W. C., SHIDEMAN F. E. Mechanism of the positive inotropic response to certain ganglionic stimulants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1959 Jul;126(3):239–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAXWELL R. A., MULL R. P., PLUMMER A. J. [2-Octahydro-1-azocinyl)-ethyl]-guanidine sulfate (CIBA 5864-SU), a new synthetic antithypertensive agents]. Experientia. 1959 Jul 15;15:267–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02158076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORAN N. C., PERKINS M. E. Adrenergic blockade of the mammalian heart by a dichloro analogue of isoproterenol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1958 Nov;124(3):223–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAASONEN M. K., KRAYER O. The release of norepinephrine from the mammalian heart by reserpine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1958 Jun;123(2):153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAAB W., GIGEE W. Specific avidity of the heart muscle to absorb and store epinephrine and norepinephrine. Circ Res. 1955 Nov;3(6):553–558. doi: 10.1161/01.res.3.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHORE P. A., OLIN J. S. Identification and chemical assay of norepinephrine in brain and other tissues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1958 Mar;122(3):295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON EULER U. S., PURKHOLD A. Effect of sympathetic denervation on the noradrenaline and adrenaline content of the spleen, kidney, and salivary glands in the sheep. Acta Physiol Scand. 1951;24(2-3):212–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1951.tb00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]