Abstract

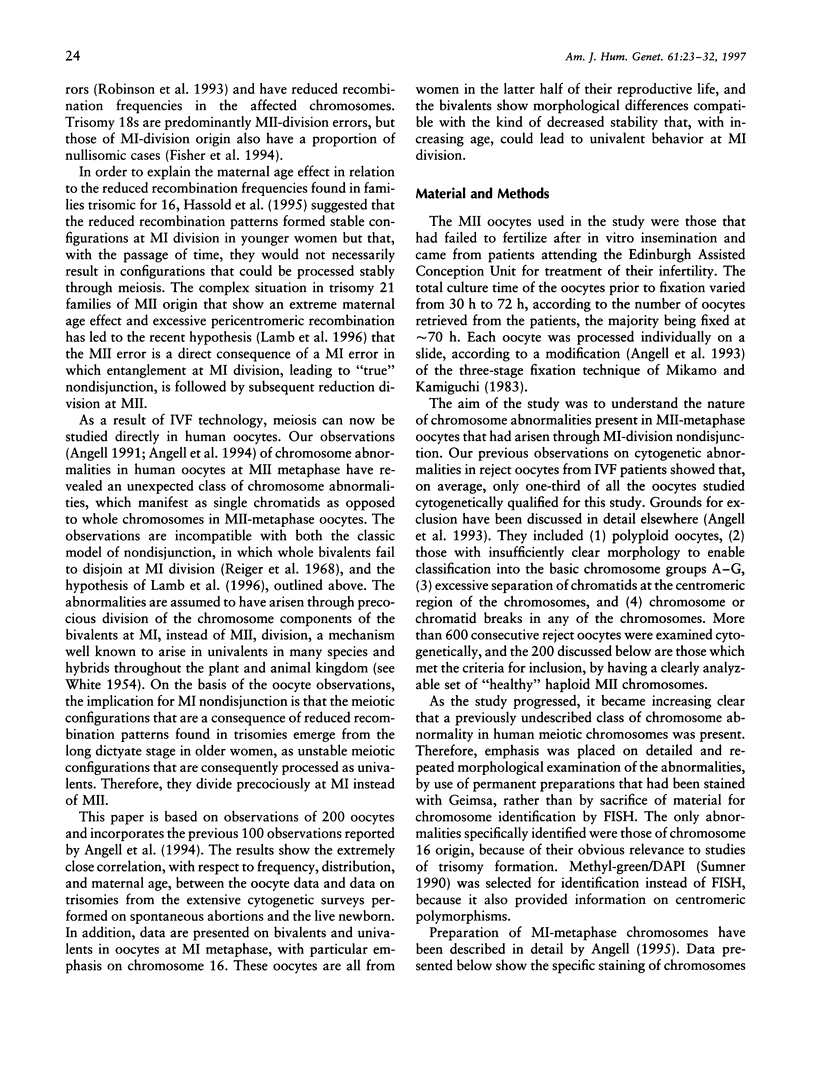

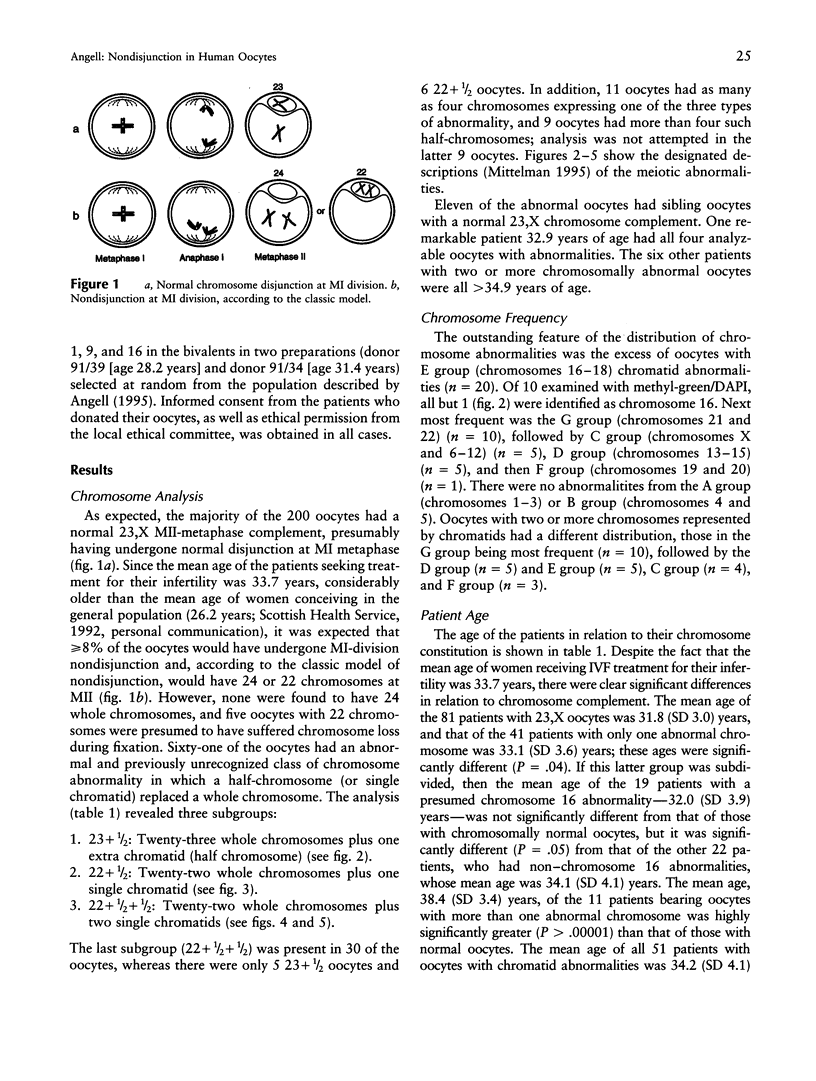

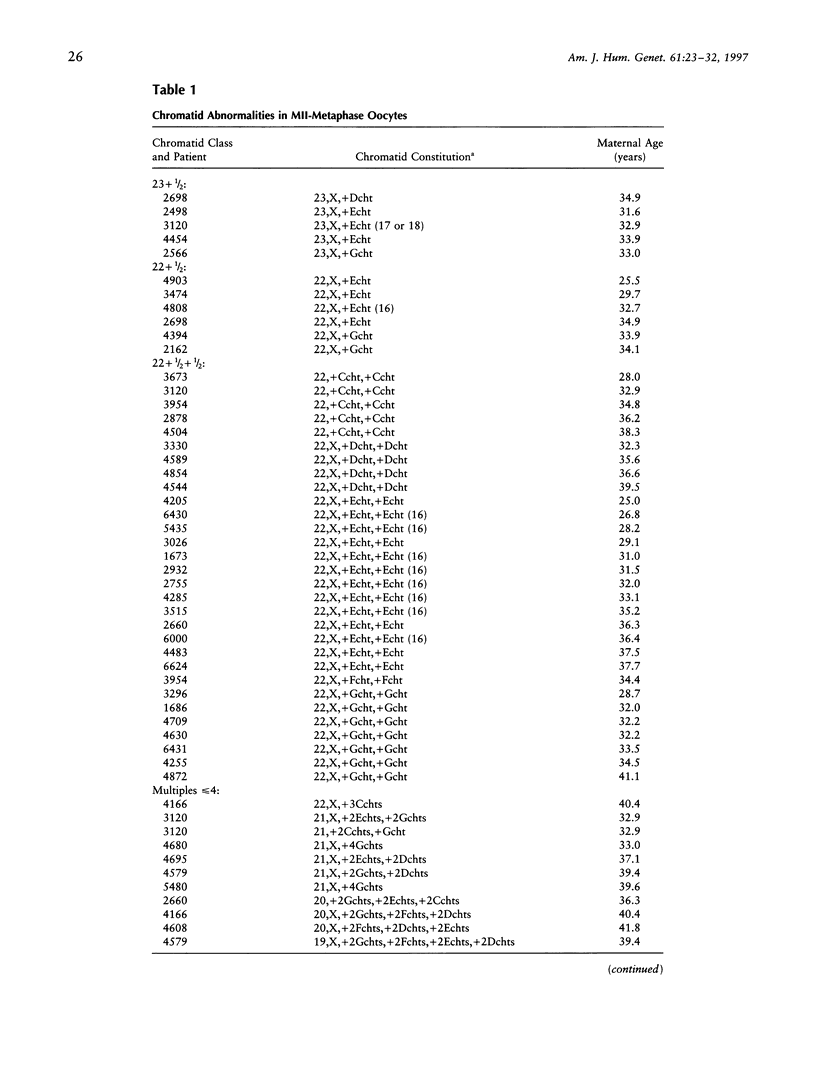

Reject oocytes from in vitro-fertilization patients are currently the only practical source of human oocyte material available for meiotic studies in women. Two hundred clearly analyzable second meiotic (MII) metaphase oocytes from 116 patients were examined for evidence of first meiotic (MI) division errors. The chromosome results, in which 67% of oocytes had a normal 23,X chromosome complement but none had an extra whole chromosome, cast doubt on the relevance, to human oocytes, of those theories of nondisjunction that propose that both chromosomes of the bivalent fail to disjoin at MI so that both move to one pole and result in an additional whole chromosome at MII metaphase. The only class of abnormality found in the MII oocytes had single chromatids (half-chromosomes) replacing whole chromosomes. Analysis of the chromosomally abnormal oocytes revealed an extremely close correlation with data on trisomies in spontaneous abortions, with respect to chromosome distribution, frequency, and maternal age, and indicated the likelihood of the chromatid abnormalities being the MI-division nondisjunction products that lead to trisomy formation after fertilization. The most likely derivation of the abnormalities is through a from of misdivision process usually associated with univalents, in which the centromeres divide precociously at MI, instead of MII, division. In the light of recent data that show that altered recombination patterns of the affected chromosomes are a key feature of most MI-division trisomies, the oocyte data imply that the vulnerable meiotic configurations arising from altered recombination patterns are processed as functional univalents in older women. Preliminary evidence from MI-metaphase oocytes supports this view.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Angell R. R. Predivision in human oocytes at meiosis I: a mechanism for trisomy formation in man. Hum Genet. 1991 Feb;86(4):383–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00201839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angell R. R., Xian J., Keith J. Chromosome anomalies in human oocytes in relation to age. Hum Reprod. 1993 Jul;8(7):1047–1054. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angell R. R., Xian J., Keith J., Ledger W., Baird D. T. First meiotic division abnormalities in human oocytes: mechanism of trisomy formation. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1994;65(3):194–202. doi: 10.1159/000133631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey T., Dale B., Cohen J., Munné S. Association between nondisjunction and maternal age in meiosis-II human oocytes. Am J Hum Genet. 1996 Jul;59(1):176–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J. M., Harvey J. F., Morton N. E., Jacobs P. A. Trisomy 18: studies of the parent and cell division of origin and the effect of aberrant recombination on nondisjunction. Am J Hum Genet. 1995 Mar;56(3):669–675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T. J., Jacobs P. A. Trisomy in man. Annu Rev Genet. 1984;18:69–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.18.120184.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T., Merrill M., Adkins K., Freeman S., Sherman S. Recombination and maternal age-dependent nondisjunction: molecular studies of trisomy 16. Am J Hum Genet. 1995 Oct;57(4):867–874. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T., Warburton D., Kline J., Stein Z. The relationship of maternal age and trisomy among trisomic spontaneous abortions. Am J Hum Genet. 1984 Nov;36(6):1349–1356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S. A., Edwards R. G. Chiasma frequency and maternal age in mammals. Nature. 1968 Apr 6;218(5136):22–28. doi: 10.1038/218022a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultén M. Chiasma distribution at diakinesis in the normal human male. Hereditas. 1974;76(1):55–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1974.tb01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P., LeMaire R., Embury P., Sheean L., Mroz K. Analysis of chromosome behavior in intact mammalian oocytes: monitoring the segregation of a univalent chromosome during female meiosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1995 Nov;4(11):2007–2012. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiguchi Y., Rosenbusch B., Sterzik K., Mikamo K. Chromosomal analysis of unfertilized human oocytes prepared by a gradual fixation-air drying method. Hum Genet. 1993 Jan;90(5):533–541. doi: 10.1007/BF00217454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb N. E., Freeman S. B., Savage-Austin A., Pettay D., Taft L., Hersey J., Gu Y., Shen J., Saker D., May K. M. Susceptible chiasmate configurations of chromosome 21 predispose to non-disjunction in both maternal meiosis I and meiosis II. Nat Genet. 1996 Dec;14(4):400–405. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthardt F. W., Palmer C. G., Yu P. Chiasma and univalent frequencies in aging female mice. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1973;12(1):68–79. doi: 10.1159/000130440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navot D., Bergh P. A., Williams M. A., Garrisi G. J., Guzman I., Sandler B., Grunfeld L. Poor oocyte quality rather than implantation failure as a cause of age-related decline in female fertility. Lancet. 1991 Jun 8;337(8754):1375–1377. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93060-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polani P. E., Jagiello G. M. Chiasmata, meiotic univalents, and age in relation to aneuploid imbalance in mice. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1976;16(6):505–529. doi: 10.1159/000130668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polani P., Dewhurst J., Fergusson I., Kelberman J. Meiotic chromosomes in a female with primary trisomic Down's syndrome. Hum Genet. 1982;62(3):277–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00333536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson W. P., Bernasconi F., Mutirangura A., Ledbetter D. H., Langlois S., Malcolm S., Morris M. A., Schinzel A. A. Nondisjunction of chromosome 15: origin and recombination. Am J Hum Genet. 1993 Sep;53(3):740–751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S. L., Petersen M. B., Freeman S. B., Hersey J., Pettay D., Taft L., Frantzen M., Mikkelsen M., Hassold T. J. Non-disjunction of chromosome 21 in maternal meiosis I: evidence for a maternal age-dependent mechanism involving reduced recombination. Hum Mol Genet. 1994 Sep;3(9):1529–1535. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.9.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S. L., Takaesu N., Freeman S. B., Grantham M., Phillips C., Blackston R. D., Jacobs P. A., Cockwell A. E., Freeman V., Uchida I. Trisomy 21: association between reduced recombination and nondisjunction. Am J Hum Genet. 1991 Sep;49(3):608–620. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed R. M. The effects of ageing on the meiotic chromosomes of male and female mice. Chromosoma. 1977 Nov 30;64(3):241–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00328080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara S., Mikamo K. Absence of correlation between univalent formation and meiotic nondisjunction in aged female Chinese hamsters. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1983;35(1):34–40. doi: 10.1159/000131833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon P. W., Freeman S. B., Sherman S. L., Taft L. F., Gu Y., Pettay D., Flanders W. D., Khoury M. J., Hassold T. J. Advanced maternal age and the risk of Down syndrome characterized by the meiotic stage of chromosomal error: a population-based study. Am J Hum Genet. 1996 Mar;58(3):628–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]