Abstract

BACKGROUND—Almost 4% of the population suffer from food allergy which is an adverse reaction to food with an underlying immunological mechanism. AIMS—To characterise one of the most frequent IgE defined food allergens, fish parvalbumin. METHODS—Tissue and subcellular distribution of carp parvalbumin was analysed by immunogold electron microscopy and cell fractionation. Parvalbumin was purified to homogeneity, analysed by mass spectrometry and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, and its allergenic activity was analysed by IgE binding and basophil histamine release tests. RESULTS—The isoelectric point (pI) 4.7 form of carp parvalbumin, a three EF-hand calcium-binding protein, was purified to homogeneity. CD analysis revealed a remarkable stability and refolding capacity of calcium-bound parvalbumin. This may explain why parvalbumin, despite cooking and exposure to the gastrointestinal tract, can sensitise patients. Purified parvalbumin reacted with IgE of more than 95% of individuals allergic to fish, induced dose-dependent basophil histamine release and contained, on average, 83% of the IgE epitopes present in other fish species. Calcium depletion reduced the IgE binding capacity of parvalbumin which, according to CD analysis, may be due to conformation-dependent IgE recognition. CONCLUSIONS—Purified carp parvalbumin represents an important cross reactive food allergen. It can be used for in vitro and in vivo diagnosis of fish-induced food allergy. Our finding that the apo-form of parvalbumin had a greatly reduced IgE binding capacity indicates that this form may be a candidate for safe immunotherapy of fish-related food allergy. Keywords: food allergy; parvalbumin; circular dichroism; epitopes; antibodies; immunochemistry

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (257.4 KB).

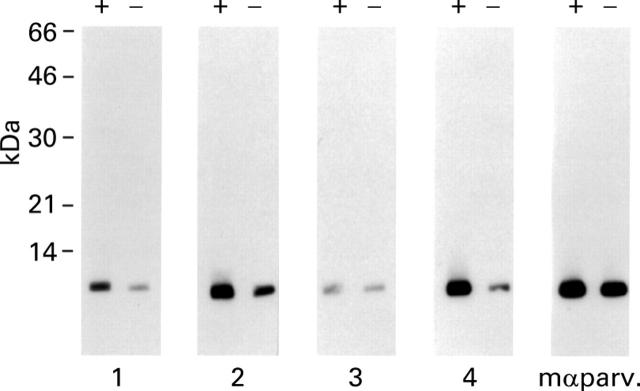

Figure 1 .

Subcellular localisation of parvalbumin in carp muscle and liver by immunogold electron microscopy. Bright field micrograph of ultrathin sections of carp muscle labelled with a monoclonal antibody against parvalbumin (A) and with an isotype matched control antibody without specificity for parvalbumin (B). (C) A section from carp liver labelled with the monoclonal antibody against parvalbumin. ER, endoplasmic reticulum, M, mitochondria, and N, nucleus. Magnification in all micrographs is 58 000 ×. The bars correspond to 0.25 µm. Black dots represent bound gold particles.

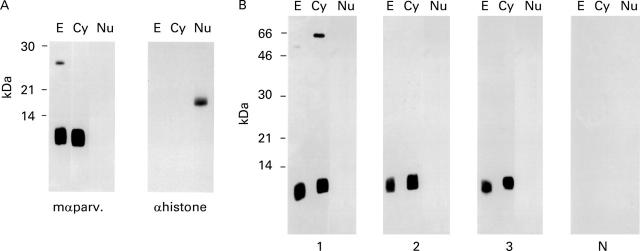

Figure 2 .

Detection of parvalbumin in subcellular carp muscle fractions. (A) Detection of parvalbumin (mαparv.) and histone (αhistone) immunoreactivity in total (E), cytoplasmic (Cy), and nuclear (Nu) western-blotted carp muscle extracts with monoclonal antibodies. (B) Incubation of nitrocellulose strips containing total (E), cytoplasmic (Cy) and nuclear (Nu) carp muscle extracts with sera from three patients allergic to fish (Nos 1, 2, and 3) and from a non-atopic individual (N).

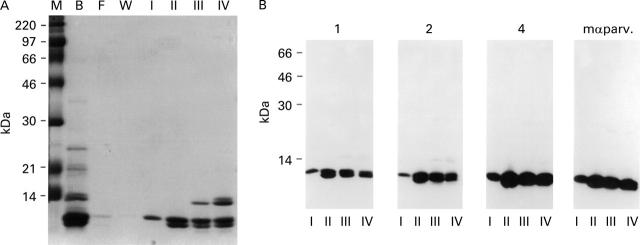

Figure 3 .

Purification of carp parvalbumin. (A) Purification of carp parvalbumin isoforms by DEAE chromatography monitored by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Parvalbumin-enriched soluble carp muscle protein fraction obtained by ammonsulphate precipitation (lane B) was applied to a DEAE column. Lanes F and W represent the flow through and column wash fractions, respectively. Lanes I-IV contain aliquots of parvalbumin fractions eluted from the DEAE column. (B) Nitrocellulose-blotted parvalbumin isoform-containing fractions I-IV were exposed to sera from three patients allergic to fish (Nos 1, 2, and 4) and to a mouse monoclonal anti-parvalbumin antibody (mαparv.).

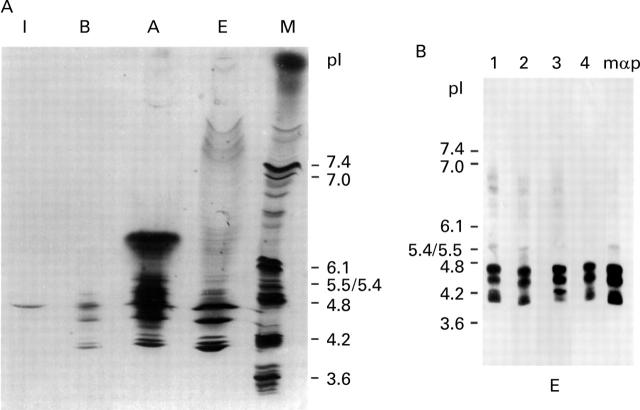

Figure 4 .

Characterisation of pI isoforms of carp parvalbumin by IEF. (A) Total carp muscle extract (lane E), soluble fraction after extract boiling (lane A) and after ammonsulphate precipitation (lane B), and a single purified carp parvalbumin isoform present in fraction I eluted from the DEAE column were separated by IEF in an agarose gel (pH 3-7) and stained with Coomassie blue. Lane M represents a standard pI marker (pI range 3.6-10.2). (B) Detection of pI isoforms of carp parvalbumin on membrane-blotted, IEF-separated carp muscle extract (E) with serum IgE from four patients allergic to fish (Nos 1, 2, 3, and 4) and with a mouse monoclonal anti-parvalbumin antibody (mαp).

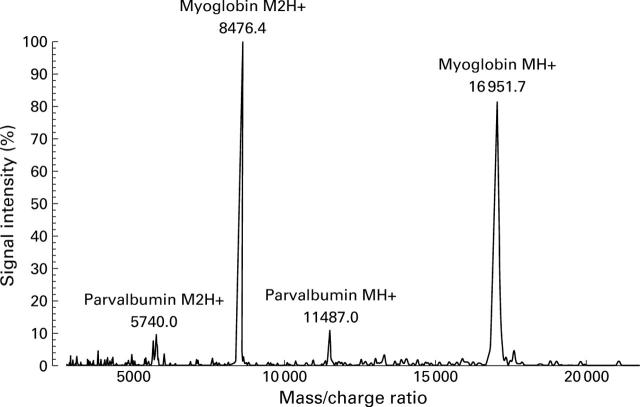

Figure 5 .

Mass spectroscopic analysis of purified carp parvalbumin pI 4.7. The x axis shows the mass/charge ratio; signal intensity is displayed on the y axis as a percentage related to the most intensive signal obtained in the investigated mass range.

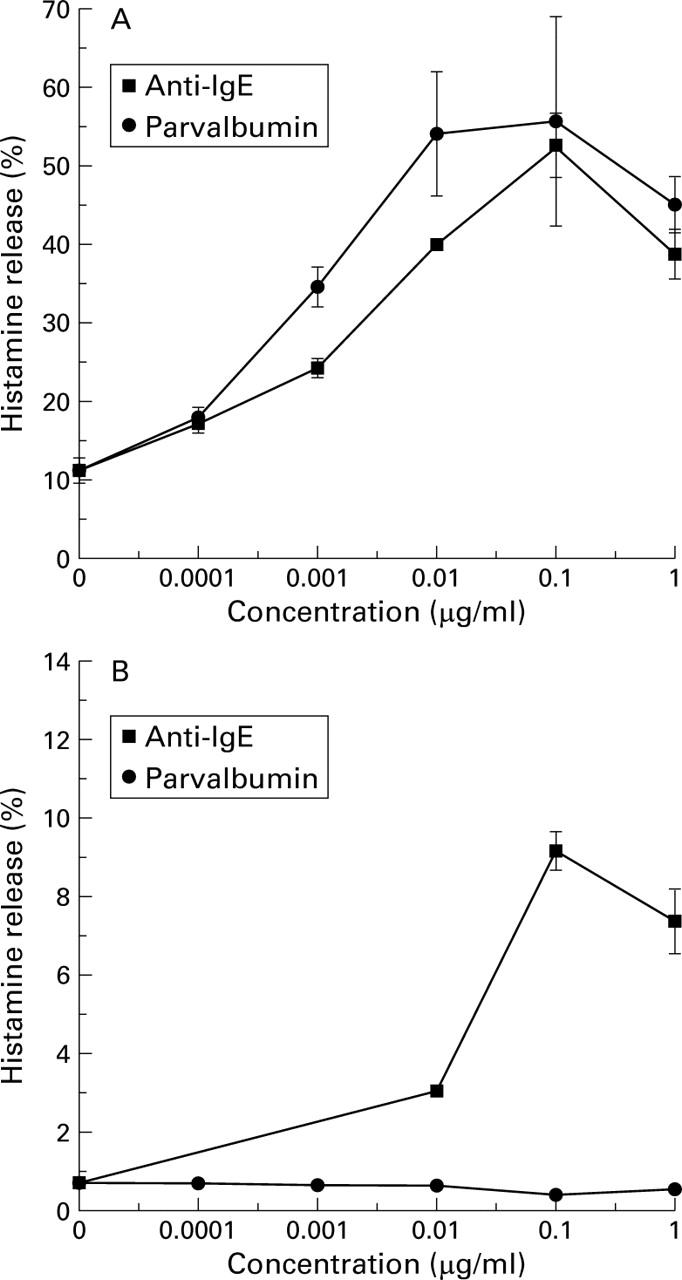

Figure 6 .

Induction of basophil histamine release with purified carp parvalbumin pI 4.7. Basophils from a patient allergic to fish (A) and from a non-atopic individual (B), were incubated with various concentrations of purified carp parvalbumin pI 4.7 and a monoclonal anti-human IgE antibody. The percentage of histamine release is shown.

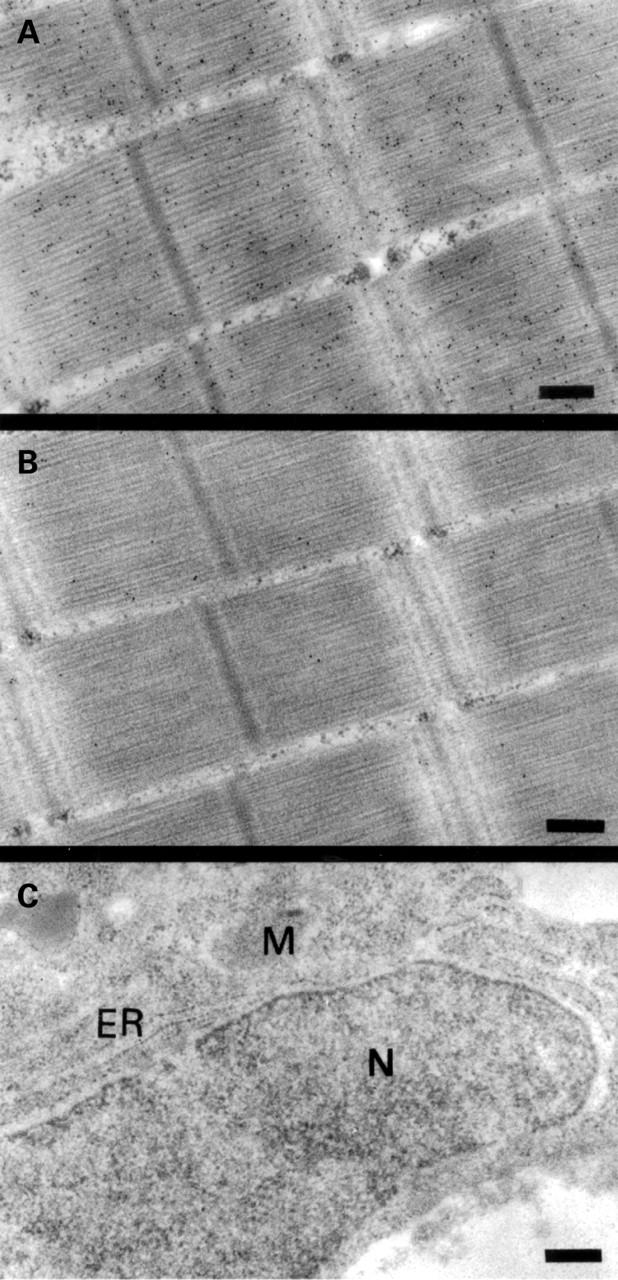

Figure 7 .

Calcium-dependent IgE recognition of purified carp parvalbumin pI 4.7. Nitrocellulose-blotted carp parvalbumin pI 4.7 was exposed to serum IgE from four patients allergic to fish (Nos 1, 2, 3, and 4) and to a mouse monoclonal anti-parvalbumin antibody (mαparv.) in the presence (+) and absence (−) of calcium.

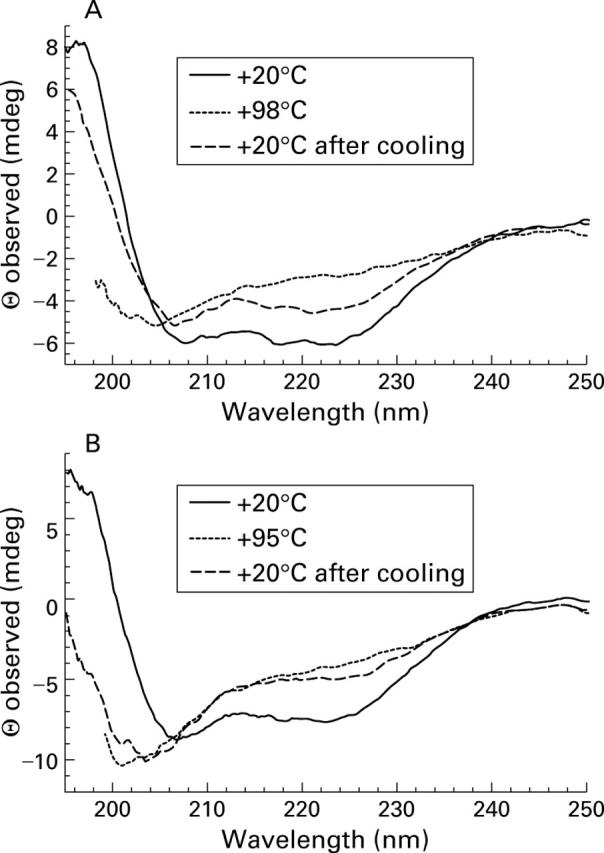

Figure 8 .

Far-ultraviolet circular dichroism analysis of purified carp parvalbumin pI 4.7. (A) Calcium-bound parvalbumin pI 4.7 at +20°C, +98°C and +20°C after cooling from +98°C. (B) Carp parvalbumin pI 4.7 in the presence of EGTA 5 mM at +20°C, +95°C and +20°C after cooling from +95°C. Spectra are expressed as observed ellipticity (Θ) at a given wave length.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aas K., Elsayed S. M. Characterization of a major allergen (cod). Effect of enzymic hydrolysis on the allergenic activity. J Allergy. 1969 Dec;44(6):333–343. doi: 10.1016/0021-8707(69)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins F. M., Steinberg S. S., Metcalfe D. D. Evaluation of immediate adverse reactions to foods in adult patients. I. Correlation of demographic, laboratory, and prick skin test data with response to controlled oral food challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985 Mar;75(3):348–355. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(85)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchtold M. W. Structure and expression of genes encoding the three-domain Ca2+-binding proteins parvalbumin and oncomodulin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989 Dec 22;1009(3):201–215. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(89)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhisel-Broadbent J., Scanlon S. M., Sampson H. A. Fish hypersensitivity. I. In vitro and oral challenge results in fish-allergic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992 Mar;89(3):730–737. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90381-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhisel-Broadbent J., Strause D., Sampson H. A. Fish hypersensitivity. II: Clinical relevance of altered fish allergenicity caused by various preparation methods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992 Oct;90(4 Pt 1):622–629. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90135-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff S. C., Herrmann A., Manns M. P. Prevalence of adverse reactions to food in patients with gastrointestinal disease. Allergy. 1996 Nov;51(11):811–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff S. C., Mayer J., Wedemeyer J., Meier P. N., Zeck-Kapp G., Wedi B., Kapp A., Cetin Y., Gebel M., Manns M. P. Colonoscopic allergen provocation (COLAP): a new diagnostic approach for gastrointestinal food allergy. Gut. 1997 Jun;40(6):745–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.6.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum H. E., Lehky P., Kohler L., Stein E. A., Fischer E. H. Comparative properties of vertebrate parvalbumins. J Biol Chem. 1977 May 10;252(9):2834–2838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet J., Lockey R., Malling H. J. Allergen immunotherapy: therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. A WHO position paper. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998 Oct;102(4 Pt 1):558–562. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiteneder H., Pettenburger K., Bito A., Valenta R., Kraft D., Rumpold H., Scheiner O., Breitenbach M. The gene coding for the major birch pollen allergen Betv1, is highly homologous to a pea disease resistance response gene. EMBO J. 1989 Jul;8(7):1935–1938. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03597.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel-Koomen C., Ortolani C., Aas K., Bindslev-Jensen C., Björkstén B., Moneret-Vautrin D., Wüthrich B. Adverse reactions to food. European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology Subcommittee. Allergy. 1995 Aug;50(8):623–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1995.tb02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugajska-Schretter A., Elfman L., Fuchs T., Kapiotis S., Rumpold H., Valenta R., Spitzauer S. Parvalbumin, a cross-reactive fish allergen, contains IgE-binding epitopes sensitive to periodate treatment and Ca2+ depletion. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998 Jan;101(1 Pt 1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio M. R., Baier W., Schärer L., de Viragh P. A., Gerday C. Monoclonal antibodies directed against the calcium binding protein parvalbumin. Cell Calcium. 1988 Apr;9(2):81–86. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(88)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio M. R., Heizmann C. W. Calcium-binding protein parvalbumin as a neuronal marker. Nature. 1981 Sep 24;293(5830):300–302. doi: 10.1038/293300a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq J. P., Tinant B., Parello J., Rambaud J. Ionic interactions with parvalbumins. Crystal structure determination of pike 4.10 parvalbumin in four different ionic environments. J Mol Biol. 1991 Aug 20;220(4):1017–1039. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90369-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Buske L. M. Introduction: basophil histamine release and the diagnosis of food allergy. Allergy Proc. 1993 Jul-Aug;14(4):243–249. doi: 10.2500/108854193778811955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed S., Bennich H. The primary structure of allergen M from cod. Scand J Immunol. 1975;4(2):203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1975.tb02618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Takazawa K., Onaya T. Parvalbumin exists in rat endocrine glands. Endocrinology. 1985 Aug;117(2):527–531. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-2-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M., Pechère J. F., Haiech J., Demaille J. G. Evolutionary diversification of structure and function in the family of intracellular calcium-binding proteins. J Mol Evol. 1979 Nov;13(4):331–352. doi: 10.1007/BF01731373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M., Pechère J. F. The evolution of muscular parvalbumins investigated by the maximum parsimony method. J Mol Evol. 1977 Apr 29;9(2):131–158. doi: 10.1007/BF01732745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiech J., Derancourt J., Pechère J. F., Demaille J. G. Magnesium and calcium binding to parvalbumins: evidence for differences between parvalbumins and an explanation of their relaxing function. Biochemistry. 1979 Jun 26;18(13):2752–2758. doi: 10.1021/bi00580a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heizmann C. W., Berchtold M. W., Rowlerson A. M. Correlation of parvalbumin concentration with relaxation speed in mammalian muscles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Dec;79(23):7243–7247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heizmann C. W., Hunziker W. Intracellular calcium-binding proteins: more sites than insights. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991 Mar;16(3):98–103. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90041-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura M. Calcium binding and conformational response in EF-hand proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996 Jan;21(1):14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretsinger R. H., Nockolds C. E. Carp muscle calcium-binding protein. II. Structure determination and general description. J Biol Chem. 1973 May 10;248(9):3313–3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge M., Wright W. W., Sudhakar K., Liebman P. A., Vanderkooi J. M. Conformational effects of calcium release from parvalbumin: comparison of computational simulations with spectroscopic investigations. Biochemistry. 1997 May 6;36(18):5363–5371. doi: 10.1021/bi962436q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehky P., Blum H. E., Stein E. A., Fischer E. H. Isolation and characterization of parvalbumins from the skeletal muscle of higher vertebrates. J Biol Chem. 1974 Jul 10;249(13):4332–4334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy J. H., Schwieger I. M., Zaidan J. R., Faraj B. A., Weintraub W. S. Evaluation of patients at risk for protamine reactions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989 Aug;98(2):200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neil C., Helbling A. A., Lehrer S. B. Allergic reactions to fish. Clin Rev Allergy. 1993 Summer;11(2):183–200. doi: 10.1007/BF02914470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauls T. L., Durussel I., Berchtold M. W., Cox J. A. Inactivation of individual Ca(2+)-binding sites in the paired EF-hand sites of parvalbumin reveals asymmetrical metal-binding properties. Biochemistry. 1994 Aug 30;33(34):10393–10400. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechère J. F., Capony J. P., Ryden L. The primary structure of the major parvalbumin from hake muscle. Isolation and general properties of the protein. Eur J Biochem. 1971 Dec 10;23(3):421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1971.tb01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechére J. F., Demaille J., Capony J. P. Muscular parvalbumins: preparative and analytical methods of general applicability. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971 May 25;236(2):391–408. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(71)90220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson H. A. Food allergy. Part 1: immunopathogenesis and clinical disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999 May;103(5 Pt 1):717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson H. A. Food allergy. Part 2: diagnosis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999 Jun;103(6):981–989. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson H. A. Food allergy. JAMA. 1997 Dec 10;278(22):1888–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiberler S., Scheiner O., Kraft D., Lonsdale D., Valenta R. Characterization of a birch pollen allergen, Bet v III, representing a novel class of Ca2+ binding proteins: specific expression in mature pollen and dependence of patients' IgE binding on protein-bound Ca2+. EMBO J. 1994 Aug 1;13(15):3481–3486. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar K., Phillips C. M., Owen C. S., Vanderkooi J. M. Dynamics of parvalbumin studied by fluorescence emission and triplet absorption spectroscopy of tryptophan. Biochemistry. 1995 Jan 31;34(4):1355–1363. doi: 10.1021/bi00004a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan R. Y., Mabuchi Y., Grabarek Z. Blocking the Ca2+-induced conformational transitions in calmodulin with disulfide bonds. J Biol Chem. 1996 Mar 29;271(13):7479–7483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Sep;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent P., Besemer J., Muhm M., Majdic O., Lechner K., Bettelheim P. Interleukin 3 activates human blood basophils via high-affinity binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jul;86(14):5542–5546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenta R., Vrtala S., Focke-Tejkl M., Bugajska-Schretter, Ball T., Twardosz A., Spitzauer S., Grönlund H., Kraft D. Genetically engineered and synthetic allergen derivatives: candidates for vaccination against type I allergy. Biol Chem. 1999 Jul-Aug;380(7-8):815–824. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenta R., Vrtala S., Laffer S., Spitzauer S., Kraft D. Recombinant allergens. Allergy. 1998 Jun;53(6):552–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb03930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesierska-Gadek J., Sauermann G. Modification of nuclear matrix proteins by ADP-ribosylation. Association of nuclear ADP-ribosyltransferase with the nuclear matrix. Eur J Biochem. 1985 Dec 2;153(2):421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Martino M., Novembre E., Galli L., de Marco A., Botarelli P., Marano E., Vierucci A. Allergy to different fish species in cod-allergic children: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990 Dec;86(6 Pt 1):909–914. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(05)80154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]