Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To demonstrate postinfarction myocardial oedema in humans with particular reference to the longitudinal course, using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). DESIGN—Prospective observational study. Subjects were studied one week, one month, three months, six months, and one year after presenting with a myocardial infarct. SETTING—Cardiology and magnetic resonance departments in a Danish university hospital. PATIENTS—10 patients (three women, seven men), mean (SEM) age 58.2 (3.20) years, with a first transmural myocardial infarct. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES—Location and duration of postinfarction myocardial oedema. RESULTS—All patients had signs of postinfarction myocardial oedema. The magnetic resonance images were evaluated by two blinded procedures, employing two MRI and two ECG observers: (1) MRI determined oedema location was compared with the ECG determined site of infarction and almost complete agreement was found; (2) the time course of postinfarction myocardial oedema was explored semiquantitatively, using an image ranking procedure. Myocardial oedema was greatest at the initial examination one week after the infarction, with a gradual decline during the following months (Spearman's rank correlation analysis: ρobserver 1 = 0.94 (p < 0.0001) and ρobserver 2 = 0.97 (p < 0.0001)). The median duration of oedema was six months. CONCLUSIONS—Postinfarction myocardial oedema seems surprisingly long lasting. This observation is of potential clinical interest because the oedema may have prognostic significance. Keywords: myocardial infarction; myocardial oedema; magnetic resonance imaging

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (122.9 KB).

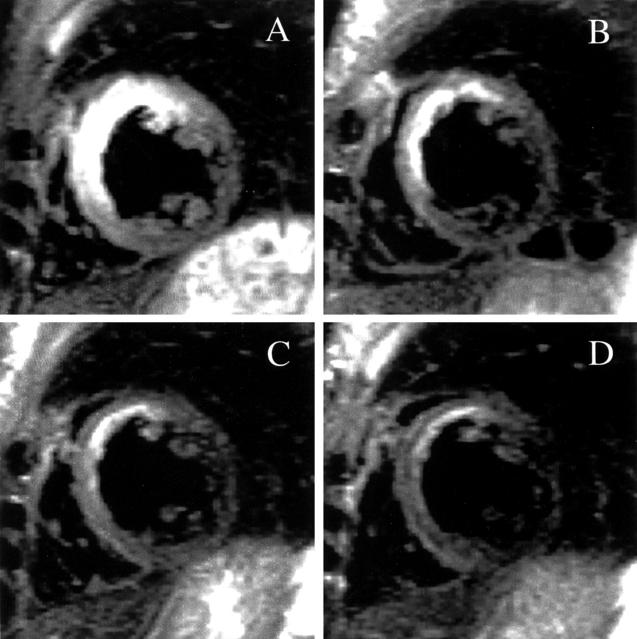

Figure 1 .

The course of postinfarction myocardial oedema (table 1, patient 9). Corresponding slices of the right and left ventricles positioned in the true short axis at mid-ventricular level from four succeeding examinations. (A) Seventh day post-myocardial infarction; (B) one month; (C) three months; (D) six months. The high signal intensity (bright) areas within the myocardium represent oedema. Notice the large extent of oedema on the seventh day affecting particularly the septum and anterior wall of the left ventricle, and the gradual decline of the oedema over the following months.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Boxt L. M., Hsu D., Katz J., Detweiler P., Mclaughlin S., Kolb T. J., Spotnitz H. M. Estimation of myocardial water content using transverse relaxation time from dual spin-echo magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1993;11(3):375–383. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(93)90070-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon P. J., Maudsley A. A., Hilal S. K., Simon H. E., Cassidy F. Sodium nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of myocardial tissue of dogs after coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986 Mar;7(3):573–579. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmensen P., Ohman E. M., Sevilla D. C., Peck S., Wagner N. B., Quigley P. S., Grande P., Lee K. L., Wagner G. S. Changes in standard electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation predictive of successful reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Dec 15;66(20):1407–1411. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. L., Mehlhorn U., Laine G. A., Allen S. J. Myocardial edema, left ventricular function, and pulmonary hypertension. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1995 Jan;78(1):132–137. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Dorado D., Oliveras J. Myocardial oedema: a preventable cause of reperfusion injury? Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Sep;27(9):1555–1563. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.9.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Dorado D., Oliveras J., Gili J., Sanz E., Pérez-Villa F., Barrabés J., Carreras M. J., Solares J., Soler-Soler J. Analysis of myocardial oedema by magnetic resonance imaging early after coronary artery occlusion with or without reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Aug;27(8):1462–1469. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.8.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand H. B., Kim R. J., Parker M. A., Fieno D. S., Judd R. M. Early assessment of myocardial salvage by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2000 Oct 3;102(14):1678–1683. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.14.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman E. R., van Jonbergen H. P., van Dijkman P. R., van der Laarse A., de Roos A., van der Wall E. E. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging studies with enzymatic indexes of myocardial necrosis for quantification of myocardial infarct size. Am J Cardiol. 1993 May 1;71(12):1036–1040. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings R. B., Schaper J., Hill M. L., Steenbergen C., Jr, Reimer K. A. Effect of reperfusion late in the phase of reversible ischemic injury. Changes in cell volume, electrolytes, metabolites, and ultrastructure. Circ Res. 1985 Feb;56(2):262–278. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd R. M., Lugo-Olivieri C. H., Arai M., Kondo T., Croisille P., Lima J. A., Mohan V., Becker L. C., Zerhouni E. A. Physiological basis of myocardial contrast enhancement in fast magnetic resonance images of 2-day-old reperfused canine infarcts. Circulation. 1995 Oct 1;92(7):1902–1910. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R. J., Fieno D. S., Parrish T. B., Harris K., Chen E. L., Simonetti O., Bundy J., Finn J. P., Klocke F. J., Judd R. M. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999 Nov 9;100(19):1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R. J., Judd R. M., Chen E. L., Fieno D. S., Parrish T. B., Lima J. A. Relationship of elevated 23Na magnetic resonance image intensity to infarct size after acute reperfused myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1999 Jul 13;100(2):185–192. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R. J., Wu E., Rafael A., Chen E. L., Parker M. A., Simonetti O., Klocke F. J., Bonow R. O., Judd R. M. The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000 Nov 16;343(20):1445–1453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine G. A. Change in (dP/dt)max as an index of myocardial microvascular permeability. Circ Res. 1987 Aug;61(2):203–208. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima J. A., Judd R. M., Bazille A., Schulman S. P., Atalar E., Zerhouni E. A. Regional heterogeneity of human myocardial infarcts demonstrated by contrast-enhanced MRI. Potential mechanisms. Circulation. 1995 Sep 1;92(5):1117–1125. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotan C. S., Bouchard A., Cranney G. B., Bishop S. P., Pohost G. M. Assessment of postreperfusion myocardial hemorrhage using proton NMR imaging at 1.5 T. Circulation. 1992 Sep;86(3):1018–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto M., McClure D. E., Schertel E. R., Andrews P. J., Jones G. A., Pratt J. W., Ross P., Myerowitz P. D. Effects of hypoproteinemia-induced myocardial edema on left ventricular function. Am J Physiol. 1998 Mar;274(3 Pt 2):H937–H944. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.3.H937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish T. B., Fieno D. S., Fitzgerald S. W., Judd R. M. Theoretical basis for sodium and potassium MRI of the human heart at 1.5 T. Magn Reson Med. 1997 Oct;38(4):653–661. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt J. W., Schertel E. R., Schaefer S. L., Esham K. E., McClure D. E., Heck C. F., Myerowitz P. D. Acute transient coronary sinus hypertension impairs left ventricular function and induces myocardial edema. Am J Physiol. 1996 Sep;271(3 Pt 2):H834–H841. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochitte C. E., Kim R. J., Hillenbrand H. B., Chen E. L., Lima J. A. Microvascular integrity and the time course of myocardial sodium accumulation after acute infarction. Circ Res. 2000 Oct 13;87(8):648–655. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubboli A., Sobotka P. A., Euler D. E. Effect of acute edema on left ventricular function and coronary vascular resistance in the isolated rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1994 Sep;267(3 Pt 2):H1054–H1061. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer S., Malloy C. R., Katz J., Parkey R. W., Buja L. M., Willerson J. T., Peshock R. M. Gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of reperfused myocardium: identification of the myocardial bed at risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Oct;12(4):1064–1072. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90477-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti O. P., Finn J. P., White R. D., Laub G., Henry D. A. "Black blood" T2-weighted inversion-recovery MR imaging of the heart. Radiology. 1996 Apr;199(1):49–57. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.1.8633172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorota S. Swelling-induced chloride-sensitive current in canine atrial cells revealed by whole-cell patch-clamp method. Circ Res. 1992 Apr;70(4):679–687. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen C., Hill M. L., Jennings R. B. Volume regulation and plasma membrane injury in aerobic, anaerobic, and ischemic myocardium in vitro. Effects of osmotic cell swelling on plasma membrane integrity. Circ Res. 1985 Dec;57(6):864–875. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.6.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita M., Gotoh F. Cascade of cell swelling: thermodynamic potential discharge of brain cells after membrane injury. Am J Physiol. 1992 Feb;262(2 Pt 2):H603–H610. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranum-Jensen J., Janse M. J., Fiolet W. T., Krieger W. J., D'Alnoncourt C. N., Durrer D. Tissue osmolality, cell swelling, and reperfusion in acute regional myocardial ischemia in the isolated porcine heart. Circ Res. 1981 Aug;49(2):364–381. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisenberg G., Prato F. S., Carroll S. E., Turner K. L., Marshall T. Serial nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of acute myocardial infarction with and without reperfusion. Am Heart J. 1988 Mar;115(3):510–518. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90798-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roos A., van Rossum A. C., van der Wall E., Postema S., Doornbos J., Matheijssen N., van Dijkman P. R., Visser F. C., van Voorthuisen A. E. Reperfused and nonreperfused myocardial infarction: diagnostic potential of Gd-DTPA--enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1989 Sep;172(3):717–720. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.3.2772179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wall E. E., van Dijkman P. R., de Roos A., Doornbos J., van der Laarse A., Manger Cats V., van Voorthuisen A. E., Matheijssen N. A., Bruschke A. V. Diagnostic significance of gadolinium-DTPA (diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid) enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in thrombolytic treatment for acute myocardial infarction: its potential in assessing reperfusion. Br Heart J. 1990 Jan;63(1):12–17. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]