Abstract

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) transcription factors regulate genes responsible for critical cellular processes. IκBα, -β, and -ε bind to NF-κBs and inhibit their transcriptional activity. The NF-κB-binding domains of IκBs contain six ankyrin repeats (ARs), which adopt a β-hairpin/α-helix/loop/α-helix/loop architecture. IκBα appears compactly folded in the IκBα·NF-κB crystal structure, but biophysical studies suggested that IκBα might be flexible even when bound to NF-κB. Amide H/2H exchange in free IκBα suggests that ARs 2–4 are compact, but ARs 1, 5, and 6 are conformationally flexible. Amide H/2H exchange is one of few techniques able to experimentally identify regions that fold upon binding. Comparison of amide H/2H exchange in free and NF-κB-bound IκBα reveals that the β-hairpins in ARs 5 and 6 fold upon binding to NF-κB, but AR 1 remains highly solvent accessible. These regions are implicated in various aspects of NF-κB regulation, such as controlling degradation of IκBα, enabling high-affinity interaction with different NF-κB dimers, and preventing NF-κB from binding to its target DNA. Thus, IκBα conformational flexibility and regions of IκBα folding upon binding to NF-κB are important attributes for its regulation of NF-κB transcriptional activity.

Keywords: amide exchange, ankyrin repeat, transcription regulation, protein dynamics, protein folding

The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) family of eukaryotic transcription factors regulate >150 target genes, which are involved in a wide variety of cellular functions (1). Numerous signals, such as inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and some bacterial and viral products, activate NF-κB (2). NF-κB-regulated gene products regulate stress and immune responses and cellular differentiation and proliferation (1–4). Aberrant NF-κB regulation is observed in many diseases, including heart disease, Alzheimer's disease, diabetes, AIDS, and many types of cancer (5, 6).

The canonical form of NF-κB is a p50·p65 heterodimer, but the NF-κB family includes five different subunits (p50, p52, p65/RelA, RelB, and cRel) (2). Inhibitor proteins, IκBα, -β, and -ε, regulate NF-κB transcriptional activity (7). In resting cells, IκB binding masks the NF-κB nuclear localization sequence (NLS), sequestering the complex in the cytosol (8, 9). Signals from many classes of stimuli activate IκB kinases (IKKs), which phosphorylate the NF-κB-bound IκB, thereby causing ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the IκB (10–15). The resulting free NF-κB translocates to the nucleus, via its exposed NLS, binds to DNA, and activates transcription of target genes (1). NF-κB activates the transcription of IκBα (16–19). Newly synthesized IκBα enters the nucleus, binds to NF-κB, and prevents it from binding DNA (20). The NF-κB·IκBα complex is exported to the cytosol via the IκBα nuclear export sequence, returning the cell to the resting state. Studies in IκBβ−/−, IκBε−/− cells show an oscillatory NF-κB response, due to rapid activation of NF-κB transcriptional activity by signal-induced IκBα degradation and strong negative feedback by NF-κB-induced IκBα production (21).

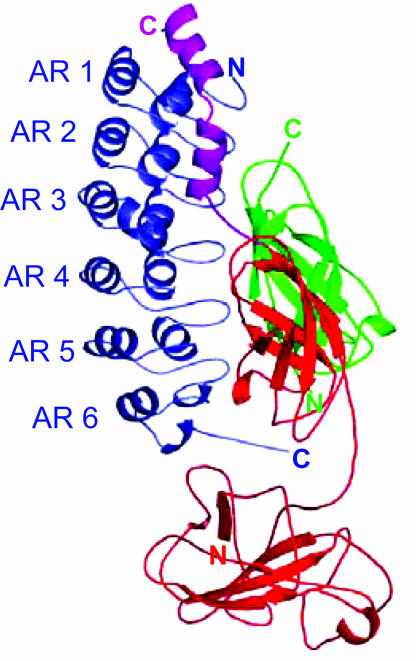

The structure of IκBα is known only in complex with NF-κB. The NF-κB-binding domain of IκBα has six ankyrin repeats (ARs) (20, 22), an ≈33-aa structural motif, composed of a β-hairpin, followed by two antiparallel α-helices, and a variable loop (Fig. 1) (23, 24). IκBα and NF-κB form an extensive noncontiguous binding surface (20, 22). IκBα ARs 1–3 contact the NF-κB (p65) NLS and its flanking helices. The β-hairpins in IκBα ARs 3–6 contact the NF-κB dimerization domains, and AR 6 and the C-terminal PEST sequence of IκBα contact the dimerization domain and the N-terminal domain of p65 (20). The human genome contains hundreds of AR proteins that generally mediate protein–protein interactions (25).

Fig. 1.

The crystal structure of IκBα (blue) bound to NF-κB (p50, green; p65, red) (22). Helix 3 and helix 4 in p65 (magenta), which flank its NLS, interact with ARs 1–3 in IκBα. The dimerization domains in both p50 and p65 form an extensive interface with IκBα ARs 3–6. The p50 and p65 dimerization domains and the p65 N-terminal domain contact the C-terminal PEST sequence of IκBα. The N-terminal domain of p50, not present in the structure, is not involved in IκBα binding (48, 49).

Amide H/2H exchange followed by mass spectrometry is a powerful tool for studying protein–protein interactions. Amide H/2H exchange probes the solvent accessibility of amide protons. Exchange half-lives vary from milliseconds for amides in unstructured peptides to days for amides in cores of globular proteins (26). Decreased solvent accessibility may result from amide proton hydrogen bonds or from solvent exclusion due to side-chain interactions (27). Protein dynamics can transiently expose regions for exchange. Generally, all of these factors determine the exchange rate, making mechanistic interpretations difficult. Mass spectrometry can detect even the rapidly exchanging amide protons on the surfaces of proteins (28, 29), which enables the identification of changes in solvent accessibility upon protein–protein binding (30, 31).

A number of proteins involved in transcriptional activation (32, 33) and cell-cycle regulation (34) are intrinsically unstructured, but fold upon binding to their targets. In the crystal structure of the IκBα·NF-κB complex (Fig. 1), IκBα appears to be compactly folded (20, 22). However, ARs 1, 5, and 6 in free IκBα readily exchange most of their amide protons, indicating that they are highly solvent accessible and perhaps unfolded (35). Circular dichroism (CD) showed that all of the secondary structure was present in both free and NF-κB-bound IκBα (35). However, CD does not probe tertiary structure or protein flexibility, both of which are probed by amide H/2H exchange. Binding of 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid (ANS) suggested that IκBα may have highly dynamic, molten-globule-like regions, even in the NF-κB-bound state (35).

In this study, we use amide H/2H exchange to compare the solvent accessibility of free and NF-κB-bound IκBα in solution. We find that the β-hairpins in ARs 5 and 6 fold upon binding to NF-κB. Because these regions are implicated in various aspects of NF-κB regulation, we conclude that IκBα conformational flexibility is a critical attribute for its regulation of NF-κB transcriptional activity.

Results

Amide H/2H Exchange in IκBα.

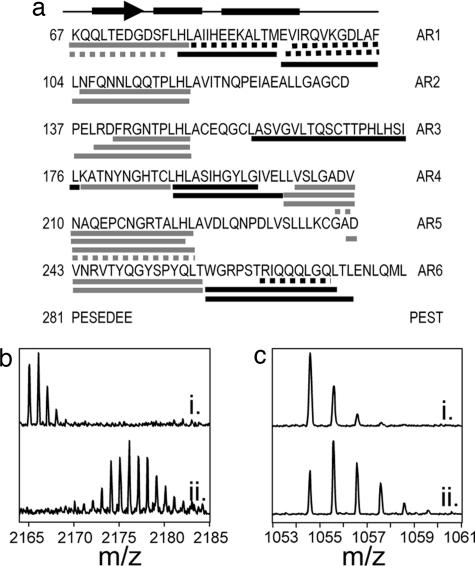

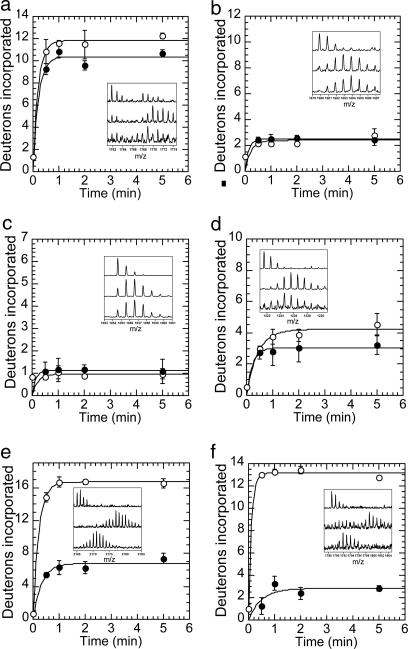

Amide H/2H exchange in free IκBα was measured previously for IκBα67–317 (35). Here, we report exchange in IκBα67–287, which is less prone to aggregation but binds to NF-κB with equal affinity and kinetics (36). Pepsin digestion of IκBα67–287 yields 25 peptides that cover 74% of the IκBα sequence (Fig. 2a). Pepsin cleavage of IκBα results in peptides with the same secondary structure in different repeats. In this study, the β-hairpins in all six ARs are covered, enabling comparison among the different repeats in this region. The β-hairpins of some ARs readily exchange amide protons for deuterons (Fig. 2b), whereas others are less solvent accessible (Fig. 2c). The β-hairpins in ARs 2–4 are only slightly deuterated, whereas those in ARs 1, 5, and 6 readily exchange most of their amide protons (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The α-helices in both ARs 1 and 4 incorporate an intermediate amount of deuterium; however, the α-helices in AR 6 exchange nearly all of their amide protons within 2 min (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The variable loops, covered in ARs 1 and 3, are both highly deuterated (Table 1). Overall, ARs 1, 5, and 6 appear to be highly solvent accessible, whereas ARs 2–4 are more protected from solvent.

Fig. 2.

IκBα β-hairpin peptides exchange to different extents. (a) Pepsin cleavage of IκBα results in 25 peptides (bars below the sequence), which cover 74% of its sequence, but 6 peptides (dashed bars) can be analyzed only qualitatively. A schematic of an AR above the sequence shows the α-helices and β-sheets (23). Peptic peptides cover the β-hairpin region in all six ARs (gray bars). (b) A peptide that covers the β-hairpin region in AR 5 (m/z of MH+ = 2,165.08) becomes highly deuterated in 2 min (ii), seen as a large shift to higher mass compared with a nondeuterated control sample (i). (c) A peptide that covers the β-hairpin region in AR 3 (MH+ = 1,054.58) incorporates fewer deuterons in 2 min (ii), seen as a moderate shift to higher mass compared with a nondeuterated control (i).

Fig. 3.

Amide H/2H exchange in IκBα β-hairpins with and without NF-κB. (a) Deuterium incorporation in the β-hairpin in AR 1, MH+ = 1,761.85, shows only small differences in the extent of exchange in free (○) and NF-κB-bound (●) IκBα that may be due to protection at the IκBα·NF-κB interface. Deuterium incorporation in the β-hairpins in AR 2, MH+ = 1,679.87 (b), and AR 3, MH+ = 1054.58 (c), show no differences, and the β-hairpin in AR 4, MH+ = 1,221.57 (d), shows only a small change in the extent of exchange between free and NF-κB-bound IκBα. The β-hairpins in AR 5, MH+ = 2,165.08 (e), and AR 6, MH+ = 1,788.89 (f), show decreases in the extent of amide exchange in NF-κB-bound IκBα that are much larger than expected for protection at the IκBα·NF-κB interface. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate reactions, and the y axis maximum corresponds to the total number of exchangeable amide protons in the peptide, except for f, which has only 13 amide protons. Insets show MALDI mass envelopes in nondeuterated controls (Top), free IκBα after 2 min of exchange (Middle), and NF-κB-bound IκBα after 2 min of exchange (Bottom).

Table 1.

Amide H/2H exchange in IκBα and IκBα bound to NF-κB

| Region | IκBα sequence | Peptide mass, m/z | Total amides | No. of amides exchanged after 2 min |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In IκBα | In IκBα·NF-κB | ||||

| AR 1 | 66–80 | 1,761.85 | 14 | 12 ± 1 | 9.1 ± 0.4 |

| 79–91 | 1,505.81 | 12 | 6.4 ± 0.02 | ND | |

| 92–103 | 1,374.77 | 11 | 8.0 ± 0.09 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | |

| AR 2 | 104–117 | 1,679.87 | 12 | 2.2 ± 0.02 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| 105–117 | 1,566.80 | 11 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | |

| AR 3 | 137–150 | 1,664.89 | 12 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| 140–150 | 1,325.71 | 9 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | |

| 142–150 | 1,054.58 | 7 | 0.9 ± 0.09 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | |

| 158–176 | 1,964.03 | 17 | 9.7 ± 0.1 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | |

| AR 4 | 177–187 | 1,221.57 | 10 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.9 |

| 188–197 | 1,067.56 | 9 | 4.2 ± 0.07 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | |

| 188–201 | 1,521.84 | 13 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.03 | |

| AR 4/5 | 201–220 | 2,028.02 | 18 | 14.1 ± 0.2 | 5.7 ± 0.07 |

| 201–223 | 2,278.16 | 20 | 17.3 ± 0.8 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | |

| 202–223 | 2,165.08 | 19 | 16.7 ± 0.3 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | |

| AR 6 | 242–257 | 1,903.92 | 14 | 15.0 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

| 243–257 | 1,788.89 | 13 | 13.4 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | |

| 258–272 | 1,767.96 | 13 | 13.2 ± 0.3 | 11.7 ± 0.8 | |

| 258–274 | 1,982.09 | 15 | 15.9 ± 0.5 | 13.0 ± 0.09 | |

Errors are standard deviations of three independent experiments. ND, not determined quantitatively because of an overlapping p50 peptide.

Fig. 4.

Amide H/2H exchange in IκBα α-helices with and without NF-κB. (a) Deuterium incorporation in the α-helices of AR 4 shows no change between free (○) and NF-κB-bound (●) IκBα. (b) NF-κB (gray) does not contact the α-helices in IκBα AR 4 (cyan) in the IκBα·NF-κB crystal structure (22) (IκBα is shown in blue). (c) Deuterium incorporation in the α-helices of AR 6 shows a small decrease in the extent of exchange in NF-κB-bound IκBα, which may be due to protection at the IκBα·NF-κB interface. (d) NF-κB (gray) contacts the α-helices in IκBα AR 6 (cyan) in the crystal structure of the IκBα·NF-κB complex (22). Interacting residues are shown with ball-and-stick representation. Error bars and the y axis maximum are as in Fig. 3, except for c, which has only 15 amide protons.

Amide H/2H Exchange in NF-κB-Bound IκBα.

Amide H/2H exchange experiments were performed on IκBα bound to NF-κB to compare the folded states of free and NF-κB-bound IκBα. Baerga-Ortiz et al. (37) demonstrated the utility of immobilizing a protein to facilitate analysis of protein–protein interactions by using amide H/2H exchange followed by mass spectrometry. Our experiments used an immobilized version of NF-κB in which the p65 subunit was covalently linked to beads, allowing removal of NF-κB during the quench step, which reduces spectral complexity from overlapping peptides. The extent of amide H/2H exchange after 2 min in IκBα was the same in the presence and absence of beads (data not shown), indicating that any changes observed are due to NF-κB binding.

The β-hairpins in ARs 5 and 6 incorporated remarkably less deuterium in the NF-κB-bound IκBα, whereas incorporation into the AR 1–4 β-hairpins varied only slightly (Figs. 3 and 5 and Table 1). The β-hairpin in AR 5 incorporates ≈10 fewer deuterons, and the β-hairpin in AR 6 incorporates ≈11 fewer deuterons after 2 min of exchange when IκBα is bound to NF-κB (Table 1). Although the peptide that covers the β-hairpin in AR 5 also covers part of the variable loop of AR 4, analysis of an overlapping peptide suggests that the differences in the deuteration in the AR 4/5 peptides are due to the β-hairpin region (data not shown). The β-hairpin in AR 1 readily exchanges most of its amide protons in both free and NF-κB-bound IκBα, but the β-hairpins in ARs 2–6 exchange only a few amide protons when IκBα is bound to NF-κB.

Fig. 5.

IκBα AR 5 and 6 β-hairpins exchange less in NF-κB-bound IκBα. IκBα from the IκBα·NF-κB crystal structure (22) is colored according to percent exchange after 2 min in free IκBα (a) and NF-κB-bound IκBα (b) (NF-κB and regions of IκBα for which exchange is not reported are shown in gray). The AR 5 and 6 β-hairpins exchange much less in NF-κB-bound IκBα than in free IκBα. The extent of exchange of the β-hairpins in ARs 5 and 6 is similar to that in ARs 2–4 in the NF-κB-bound state.

Only small changes in deuteration were observed between free and NF-κB-bound IκBα in all of the α-helices and variable loops that are covered (Figs. 4 and 5 and Table 1). The deuteration of the α-helices in AR 1 was not quantified because of an overlap with a p50 peptide; however, a qualitative analysis of the raw data shows slightly less deuterium incorporation when IκBα is bound to NF-κB (data not shown). All of AR 1 remains highly solvent accessible in NF-κB-bound IκBα. The α-helices in AR 6 still readily exchange most of their amide protons when IκBα is bound to NF-κB, despite the dramatically reduced exchange in the AR 6 β-hairpin upon binding to NF-κB.

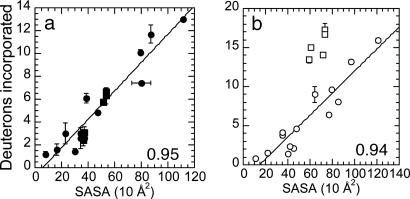

Correlation of Amide H/2H Exchange with Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA).

Amide H/2H exchange is sensitive to changes in protein conformation, protein flexibility, and protection at the binding interface. Separating the contributions from these different factors poses a major challenge for interpretation of amide H/2H exchange results. However, if the structure of the complex is available, it is possible to account for the structural and binding interface contributions to the exchange data by comparing the SASA calculated from the crystal structure with the amide H/2H exchange data (27). If the data are well correlated, then the differences in the extent of exchange between different peptides most likely result from structural differences in the regions covered by each peptic peptide. However, if the extent of exchange for a region of the protein is uncorrelated, then either the structure or the flexibility of that region must differ in solution from the crystal structure.

The SASA of IκBα in the IκBα·NF-κB complex was calculated from the available crystal structure (22) and compared with the extent of amide H/2H exchange at 2 min. The extent of exchange is highly correlated with the SASA (correlation coefficient 0.95) for all covered regions in NF-κB-bound IκBα (Fig. 6a). Because no ordered density was observed for the N-terminal residues 66–69 in the crystal structure, but a peptide (MH+ = 1,761.85) covering residues 66–80 was analyzed, the amide protons for residues 66–69 were assumed to exchange completely and subtracted from the number of amides exchanged at 2 min.

Fig. 6.

The β-hairpins of IκBα ARs 5 and 6 are conformationally flexible only in free IκBα. (a) Deuterium incorporation after 2 min in NF-κB-bound IκBα in all regions (●) is highly correlated with the SASA of the corresponding region of IκBα, calculated from the IκBα·NF-κB crystal structure (22). The extent of amide exchange in the β-hairpins in ARs 5 and 6 (■) is plotted separately for contrast with b. The correlation coefficient remained 0.95 whether or not these data were included. Because the crystal structure lacks electron density for residues 66–69, a corrected exchange (see Materials and Methods) for residues 70–80 was correlated with its SASA. (b) Deuterium incorporation after 2 min in free IκBα (○) is well correlated with the SASA of the corresponding region of IκBα (see Materials and Methods), except for the AR 5 and 6 β-hairpins (□), which exchange much more than expected if free and NF-κB-bound IκBα had the same structure and dynamics. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate exchange reactions and the deviation in SASA for the two complexes in Protein Data Bank ID 1NFI (22).

Removal of the NF-κB coordinates from the IκBα·NF-κB structure (22) provides a model structure for free IκBα, which assumes that no conformational changes occur upon binding to NF-κB. Comparison of amide H/2H exchange in free IκBα with the SASA from this structural model will indicate whether IκBα adopts similar conformations in the free and NF-κB-bound states. The extent of amide H/2H exchange at 2 min in free IκBα is highly correlated with the SASA for all regions of IκBα (Fig. 6b circles, correlation coefficient 0.94) except for the peptides that cover the β-hairpins in ARs 5 and 6 (Fig. 6b, squares). These two β-hairpins exchange much more at 2 min than predicted by the SASA of these regions.

Discussion

IκBα tightly regulates the transcriptional activity of NF-κB by binding NF-κB and sequestering it in the cytosol of resting cells (38). Elucidating changes in dynamics associated with the regulatory functions of IκBα provides critical mechanistic insight into this intricate signaling network. Here we have shown that regions of IκBα fold upon binding to NF-κB. These regions are involved in various aspects of NF-κB regulation, such as controlling degradation of IκBα, enabling high-affinity interaction with multiple NF-κB isoforms, and preventing NF-κB from binding to its target DNA.

The IκBα ARs 5 and 6 β-Hairpins Fold upon Binding to NF-κB.

The extent of exchange in NF-κB-bound IκBα is highly correlated with the SASA, indicating that IκBα is folded when bound to NF-κB (Fig. 6a). Some regions of IκBα, such as the β-hairpins in ARs 1 and 4, exchange less in the bound state, and SASA calculations account for these decreases in exchange due to interface protection. All of AR 1 and the α-helices in AR 6 are solvent accessible in both free and NF-κB-bound IκBα. Their SASA from the IκBα·NF-κB crystal structure is correspondingly high. In free IκBα, the β-hairpins in ARs 5 and 6 exchange nearly all of their amide protons (≈83% and ≈100%, respectively) and they exchange much more than expected from the SASA calculated for the IκBα from the IκBα·NF-κB crystal structure (Fig. 6b). However, their exchange in NF-κB-bound IκBα is comparable to the low extent in the β-hairpins in ARs 2–4 (Fig. 5) and is well correlated with their SASA, showing that they are folded when bound to NF-κB. Thus, the AR 5 and 6 β-hairpins are highly dynamic in free IκBα and fold upon binding to NF-κB. Indeed, IκBα equilibrium unfolding showed that ARs 5 and 6 are not part of the cooperative transition (50). Additionally, thermodynamic analysis revealed an unexpectedly large negative change in heat capacity for IκBα·NF-κB binding, indicative of the burial of additional nonpolar surface area upon binding (36). This burial can now be attributed, at least in part, to the folding of the β-hairpins in ARs 5 and 6 in IκBα upon binding to NF-κB.

AR1 Remains Highly Accessible in NF-κB-Bound IκBα.

The AR 1–NF-κB NLS helix 4 interaction (Fig. 1), which contributes one-third of the binding energy of the entire complex, is the primary determinant of the slow dissociation rate resulting in persistent NF-κB binding (36). AR 1 remained highly solvent accessible even in the complex. In accord with the expected interface protection, the solvent accessibility of the β-hairpin in AR 1 decreases only slightly upon NF-κB-binding. These results provide mechanistic insight into how release of NF-κB in response to signal is readily accomplished by proteasomal cleavage to unlock this critical interaction for rapid NF-κB activation (10–15).

Free IκBα ARs 5 and 6 Are Not Compactly Folded.

While the signal-dependent degradation of IκBα is required for release of NF-κB (10–15), a signal-independent proteasomal degradation pathway is the main route of degradation for free IκBα (38–40). IκBα degradation by 20S proteasomes is suppressed by deletion of AR 6 (41). The unfolded region required for 20S proteasome recognition is most likely AR 6, which we show is only weakly folded. Furthermore, 20S proteasome degradation is inhibited by IκBα·NF-κB binding, in which AR 6 is folded (41). Thus, NF-κB binding is the switch between the two different degradation mechanisms, which is mediated by the folding and binding of the AR 6 β-hairpin.

The Folding of AR 5 and 6 β-Hairpins upon Binding to NF-κB May Enable IκBα Binding to Different NF-κB Dimers.

The p50/p65 and p65/p565 NF-κB dimers have different gene specificities, yet IκBα binds both with similar affinity (36). Comparison of the IκBα·p50/p65 and IκBβ·p65/p65 structures suggests that IκBα ARs 5 and 6 must engage in significantly different interactions in the two complexes [supporting information (SI) Fig. 7], indicating that flexibility is critical for the AR 5 and 6 β-hairpins' ability to bind multiple targets.

Proposed Mechanism for Postinduction Gene Repression by IκBα.

DNA and IκBα binding to DNA are mutually exclusive, because IκBα AR 6 and PEST interact with NF-κB and occlude one entire face of the NF-κB DNA-binding surface (20). The postinduction gene repression by newly synthesized IκBα (21) could result from a transient ternary complex with NF-κB bound to DNA in which IκBα facilitates dissociation of NF-κB from DNA, as suggested previously (19, 42). This mechanism may require the folding upon binding of the AR 5 and 6 β-hairpins. Overall, folding upon binding is implicated in multiple aspects of NF-κB regulation, such as modulating IκBα degradation, mediating IκBα binding to different NF-κB dimers, and potentially facilitating dissociation of NF-κB from DNA.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Human IκBα67–287 was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 DE3 (43) and purified as described in refs. 35 and 36. NF-κB p65190–321 with an additional N-terminal Cys and p50248–350 were expressed in E. coli BL21 DE3 (43) and purified as described in ref. 36, except size-exclusion chromatography was performed in 10 mM Mops/150 mM NaCl/0.5 mM EDTA (pH 7.5), with 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for p50. Protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm, as described in ref. 36.

NF-κB Heterodimer Formation and Immobilization.

Purified p65 (1 mg/ml) was biotinylated by a 1-h incubation at 25°C with a 5-fold molar excess of maleimide-PEO2biotin (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Resulting soluble, monomeric protein was purified by size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 75 16/60 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated in 10 mM Mops/150 mM NaCl/0.5 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT (pH 7.5). There are three Cys residues and an engineered N-terminal Cys in p65, but mass spectrometry showed incorporation of only 1 biotin (QSTAR XL hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Heterodimer (p50/p65) was prepared by incubating p65 with a 1.2-fold molar excess of purified p50 for 2 h at 25°C. Serial additions of 50-μl aliquots of streptavidin agarose (Pierce Biotechnology), each incubated for ≈25 min at 25°C, were continued until the concentration of the p50/p65 supernatant, followed spectrophotometrically, remained stable. Aliquots that bound significant quantities of NF-κB were pooled, and unbound protein was removed by washing thrice with 10 mM Mops/150 mM NaCl/0.5 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT (pH 7.5). The beads were washed thrice more with 50 mM Tris/150 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT (pH 7.5) just before interaction with IκBα. Immobilized NF-κB was stored at 4°C and used within 2 days. The amount of immobilized NF-κB was estimated from the difference between the starting concentration of NF-κB and that of the supernatant after the last addition of beads, and, therefore, represents an upper limit for the concentration. Biotinylated p65190–321·p50248–350 was characterized previously, and it binds to IκBα with a Kd of 90 pM (36).

IκBα Peptide Identification.

IκBα was digested with pepsin as described in ref. 35, and the resulting peptides were identified by using MALDI tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) on a Q-STAR XL hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer equipped with an orthogonal MALDI source (Applied Biosystems) or a 4800 tandem time-of-flight MALDI mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems).

Free IκBα Amide H/2H Exchange.

The exchange reaction for the free IκBα protein was initiated by diluting 130 μM IκBα, in 50 mM Tris/150 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT (pH 7.5), 10-fold into 2H2O. The reaction proceeded for 0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 5 min at 25°C, and then the reaction was quenched by 6-fold dilution with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid at 0°C (sample pH = 2.2). The reaction was immediately transferred to 25 μl of immobilized pepsin (Pierce Biotechnology) and digested for 1 or 5 min. Aliquots (10 μl) of each digestion were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until analysis. Control reactions of IκBα with and without 20 μl of biotin·streptavidin agarose were equilibrated in 50 mM Tris/150 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT (pH 7.5) and exchanged for 2 min, as described above. All exchange reactions were performed in triplicate.

IκBα·NF-κB Amide H/2H Exchange.

Immobilized NF-κB was incubated with ≥1.1-fold molar excess of IκBα for >1 h at 4°C. Unbound IκBα was removed by washing five times with 50 mM Tris/150 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT (pH 7.5). The exchange reaction was initiated by diluting 20 μl of IκBα·NF-κB beads 10-fold with 2H2O; it proceeded for 0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 5 min at 25°C and then was quenched by 6-fold dilution with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid at 0°C (sample pH = 2.2), which also eluted the IκBα and some of the p50 from the immobilized NF-κB. The quenched supernatant was transferred to 25 μl of immobilized pepsin for digestion, and aliquots were frozen and stored, as described above for free IκBα. Exchange reactions were performed in triplicate.

MALDI Mass Spectrometry.

Samples were analyzed by MALDI mass spectrometry using a Voyager DE-STR mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) as described in ref. 31, except the matrix was 4.5 mg/ml and pH 2.2. To minimize back exchange, each sample was analyzed individually. The identities of deuterated peptide mass envelopes were verified by comparing MALDI MS/MS data collected on the most abundant peak of the mass envelope in samples deuterated for 5 min with data from a fully protonated sample (4800 tandem time-of-flight MALDI mass spectrometer; Applied Biosystems).

IκBα spectra were analyzed, as described in ref. 44, to determine the average number of deuterons incorporated into each peptic peptide. Side-chain and termini contributions due to residual deuterium (7.5%) were subtracted from the total number of deuterons incorporated, and only the backbone deuteration of each peptide is reported. Data were corrected for back-exchange loss of deuterons during analysis, as described in refs. 31 and 45, using the peptide of MH+ = 1,374.77 after exchange for >24 h as a reference. Back exchange was 38% for both 1-min and 5-min digestions. Kinetic plots were fit to a two-parameter exponential by using KaleidaGraph version 3.6 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

IκBα and IκBα·NF-κB SASA Calculations.

Files containing the coordinates of IκBα70–287 only and IκBα70–287·p50248–350·p65190–321 were created by copying the relevant coordinates from the crystal structure of IκBα·NF-κB, and calculations were performed separately for each copy in Protein Data Bank ID 1NFI (22). SASA calculations were performed by using Getarea (version 1.1) (46), using a radius of 1.4 Å and default atomic radii and atomic solvent parameters. The extent of exchange was compared with the total SASA because these parameters show the best correlation (27). Because the IκBα·NF-κB crystal structure shows no ordered electron density before residue 70, we assumed that the amide protons before residue 70 were fully exchanged at 2 min. Therefore, 3 deuterons were subtracted, because exchange in the N-terminal residue is already subtracted (see above), from the extent of exchange for the peptide covering residues 66–80 to generate a corrected exchange for residues 70–80 that could be compared with the SASA for those residues.

Figures were prepared by using PyMOL version 0.97 (47).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Bergqvist, J. Koeppe, G. Nubile, D. Ferreiro, and M. Guttman for many helpful discussions. S.M.E.T. was supported by a Cancer Research Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 CA009523. Research Funding was provided by National Institutes of Health Grant GM071862.

Abbreviations

- IκB

inhibitor of κB proteins

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- NLS

nuclear localization sequence

- AR

ankyrin repeat

- SASA

solvent-accessible surface area

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0605794103/DC1.

References

- 1.Pahl HL. Oncogene. 1999;18:6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Stark GR. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonizzi G, Karin M. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A, Takada Y, Boriek AM, Aggarwal BB. J Mol Med. 2004;82:434–448. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0555-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greten FR, Karin M. Cancer Lett. 2004;206:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. Science. 1988;242:540–546. doi: 10.1126/science.3140380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin AS., Jr Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen ZJ, Parent L, Maniatis T. Cell. 1996;84:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traenckner EB, Baeuerle PA. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1995;19:79–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1995.supplement_19.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Traenckner EB, Pahl HL, Henkel T, Schmidt KN, Wilk S, Baeuerle PA. EMBO J. 1995;14:2876–2883. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traenckner EB, Wilk S, Baeuerle PA. EMBO J. 1994;13:5433–5441. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown K, Gerstberger S, Carlson L, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Science. 1995;267:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.7878466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Martin R, Vanhove B, Cheng Q, Hofer E, Csizmadia V, Winkler H, Bach FH. EMBO J. 1993;12:2773–2779. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun SC, Ganchi PA, Ballard DW, Greene WC. Science. 1993;259:1912–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.8096091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown K, Park S, Kanno T, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2532–2536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott ML, Fujita T, Liou HC, Nolan GP, Baltimore D. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1266–1276. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huxford T, Huang DB, Malek S, Ghosh G. Cell. 1998;95:759–770. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D. Science. 2002;298:1241–1245. doi: 10.1126/science.1071914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs MD, Harrison SC. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosavi LK, Minor DL, Jr, Peng ZY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16029–16034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252537899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohl A, Binz HK, Forrer P, Stumpp MT, Plückthun A, Grütter MG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1700–1705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337680100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bork P. Proteins. 1993;17:363–374. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Englander SW, Sosnick TR, Englander JJ, Mayne L. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:18–23. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80090-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Truhlar SME, Croy CH, Torpey JW, Koeppe JR, Komives EA. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1490–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dharmasiri K, Smith DL. Anal Chem. 1996;68:2340–2344. doi: 10.1021/ac9601526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Croy CH, Koeppe JR, Bergqvist S, Komives EA. Biochem. 2004;43:5246–5255. doi: 10.1021/bi0499718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandell JG, Baerga-Ortiz A, Akashi S, Takio K, Komives EA. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:575–589. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandell JG, Falick AM, Komives EA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14705–14710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radhakrishnan I, Perez-Alvarado GC, Parker D, Dyson HJ, Montminy MR, Wright PE. Cell. 1997;91:741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kriwacki RW, Hengst L, Tennant L, Reed SI, Wright PE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11504–11509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croy CH, Bergqvist S, Huxford T, Ghosh G, Komives EA. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1767–1777. doi: 10.1110/ps.04731004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergqvist S, Croy CH, Kjaergaard M, Huxford T, Ghosh G, Komives EA. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baerga-Ortiz A, Hughes CA, Mandell JG, Komives EA. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1300–1308. doi: 10.1110/ps.4670102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tergaonkar V, Correa RG, Ikawa M, Verma IM. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:921–923. doi: 10.1038/ncb1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pando MP, Verma IM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21278–21286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002532200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krappmann D, Wulczyn FG, Scheidereit C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1724–1730. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvarez-Castelao B, Castano JG. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4797–4802. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zabel U, Baeuerle PA. Cell. 1990;61:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90806-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Studier FW, Rosenberg AH, Dunn JJ, Dubendorff JW. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mandell JG, Falick AM, Komives EA. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3987–3995. doi: 10.1021/ac980553g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes CA, Mandell JG, Anand GS, Stock AM, Komives EA. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:967–976. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fraczkiewicz R, Braun W. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeLano WL. PyMol. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. version 0.97. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malek S, Huxford T, Ghosh G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25427–25435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phelps CB, Sengchanthalangsy LL, Huxford T, Ghosh G. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29840–29846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferreiro DU, Cervantes CF, Truhlar SME, Cho SS, Wolynes PG, Komives EA. J Mol Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.044. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.