Abstract

MicroRNAs are small, ≈21- to 24-nt RNAs that have been found to regulate gene expression. miR-206 is a microRNA that is expressed at high levels in Drosophila, zebrafish, and mouse skeletal muscle and is thought to be involved in the attainment and/or maintenance of the differentiated state. We used locked nucleic acid probes for in situ hybridization analysis of the intracellular localization of miR-206 during differentiation of rat myogenic cells. Like most microRNAs, which are presumed to suppress translation of target mRNAs, we found that miR-206 occupies a cytoplasmic location in cultured myoblasts and differentiated myotubes and that its level increases in myotubes over the course of differentiation, consistent with previous findings in muscle tissue in vivo. However, to our surprise, we also observed miR-206 to be concentrated in nucleoli. A probe designed to be complementary to the precursor forms of miR-206 gave no nucleolar signal. We characterized the intracellular localization of miR-206 at higher spatial resolution and found that a substantial fraction colocalizes with 28S rRNA in both the cytoplasm and the nucleolus. miR-206 is not concentrated in either the fibrillar centers of the nucleolus or the dense fibrillar component, where ribosomal RNA transcription and early processing occur, but rather is localized in the granular component, the region of the nucleolus where final ribosome assembly takes place. These results suggest that miR-206 may associate both with nascent ribosomes in the nucleolus and with exported, functional ribosomes in the cytoplasm.

Keywords: microRNA, myogenesis, nuclear structure, RNA localization, ribosomal RNA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, ≈21- to 24-nt regulatory RNAs that contribute significantly to the control of gene expression. In many cases they have been found to be involved in tissue-specific translational control and are often loosely complementary to short “seed” sequences in the 3′ UTR of target mRNAs (1–4). This type of control would be expected to occur in the cytoplasm, of course, but most studies have looked at miRNAs in whole-cell extracts and so have not defined their intracellular locations. There is also evidence that small RNAs operate as both positive and negative regulators of transcription, often by altering the methylation state of chromatin (2, 5).

Until recently it has been difficult to visualize miRNAs by in situ hybridization because their small size makes them difficult to target specifically. However, with the advent of locked nucleic acid (LNA) probes (6), specific hybridization to miRNAs is now possible (7, 8). An LNA probe is a phosphodiester-bonded oligodeoxynucleotide that contains at least one 2′-O,4′-C-methylene-β-d-ribofuranosyl nucleotide (LNA monomer). The presence of multiple LNA monomers in an oligodeoxynucleotide probe causes the resulting DNA:RNA hybrid to resemble an A-type RNA helix. RNA hybrids formed with LNA probes exhibit a significantly increased Tm and ΔTm for mismatches compared with unmodified oligodeoxynucleotides, allowing for the specific detection of small RNA targets (6). miRNAs involved in myogenesis have been identified by LNA probe in situ hybridization studies carried out on the embryonic musculature of a number of species including zebrafish, Drosophila, and mouse (8–10). miR-1 is the most well characterized of these myogenesis-related miRNAs and is highly expressed in both cardiac and skeletal muscle (9–11), whereas other miRNAs, such as miR-206, appear to be expressed at high levels in skeletal muscle only (8, 12, 13).

It is thought that most miRNAs, including the aforementioned muscle-expressed ones, are concentrated in the cytoplasm (4, 14), but this has not been investigated in detail. The embryos investigated are not well suited for high-spatial-resolution analysis because intracellular structures are more difficult to discern when cells overlap one another in the optical z axis. Therefore, we decided to determine the intracellular localization of specific miRNAs in single cultured myogenic cells using in situ hybridization followed by high-resolution imaging microscopy. We report here an unanticipated localization pattern for the muscle-specific miRNA, miR-206, in a rat myogenic cell line. Using LNAs as hybridization probes, we found that miR-206 is not only distributed throughout the cytoplasm as expected but also is concentrated in the nucleolus. Furthermore, we demonstrate that miR-206 partially colocalizes with 28S rRNA in the cytoplasm and, remarkably, also substantially colocalizes with 28S rRNA in the granular component (GC) of the nucleolus.

Results

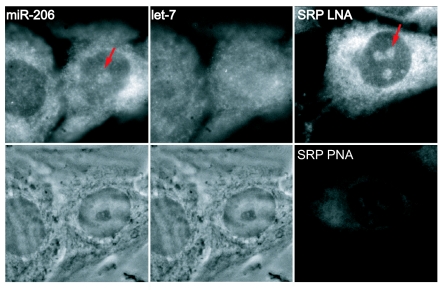

To detect and localize the very small targets represented by miRNAs, we exploited the higher specificity and hybridization efficiency of LNA probes (6–8). Fig. 1 shows typical in situ hybridization patterns obtained in a rat myogenic cell line with LNAs directed against two miRNAs, miR-206 and let-7, as well as one directed against signal recognition particle (SRP) RNA. The miR-206 and let-7 results shown here were detected in a dual hybridization experiment; similar results were obtained in experiments in which the probes were hybridized separately. It can be seen that the probe for miR-206 hybridized most extensively to nucleolar and cytoplasmic sites, with some nucleoplasmic signal, whereas the probe for let-7 gave a different pattern with a more uniform intracellular distribution overall. The hybridization pattern of SRP RNA with its LNA probe produced the same intranuclear pattern as was obtained by using peptide nucleic acid probes (SRP PNA in Fig. 1 Lower Right; also see ref. 15) and phosphodiester backbone probes (16), but hybridization to SRP RNA was often stronger using the LNA probe (Fig. 1, compare Upper Right and Lower Right). In both the miR-206 and SRP LNA hybridizations, the ratio of nucleolar:nuclear signal varied from ≈2:1 to almost 1:1, whereas in cells probed for let-7 the nucleolar signal levels never were higher than nucleoplasmic levels.

Fig. 1.

In situ hybridization pattern of miR-206 compared with let-7 and SRP RNA. (Upper) Distribution of signal after in situ hybridization using LNA probes to miR-206, let-7, and SRP RNA. Images are not scaled to the same intensity ranges. All probes were cy3-labeled except let-7, which was fluorescein-labeled; miR-206 and let-7 patterns are shown after a dual hybridization experiment. (Lower) The corresponding phase images for miR-206 and let-7. (Lower Right) The hybridization pattern to SRP RNA using a peptide nucleic acid probe. PNA, peptide nucleic acid. Arrows point to the nucleolus. Each image is 35 μm wide.

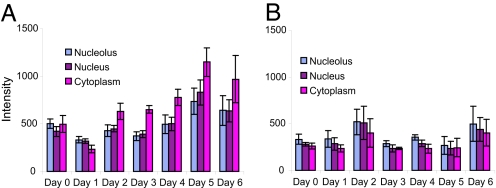

We next assayed the levels of miR-206 during myogenic differentiation. L6 myoblasts were grown in 2% horse serum to induce myotube formation (17) and subjected to in situ hybridization for miR-206 at various times. The amount of signal present in the cytoplasm, the nucleoplasm, and the nucleolus was quantified after digital images were captured. As can be seen in Fig. 2A, the amount of miR-206 in the cytoplasm increased significantly during differentiation, but the amounts in the nucleoplasm and the nucleolus remained more constant. When a scrambled sequence LNA probe was used, a low, rather constant level of signal was obtained over the course of differentiation (Fig. 2B). The observed increase in cytoplasmic miR-206 during myogenesis (Fig. 2A) is consistent with earlier results showing that total cellular levels of miR-206 increase during embryonic muscle differentiation (10) and also increase during differentiation of another myogenic cell line (13, 18).

Fig. 2.

miR-206 increases during myogenesis. (A) Histogram showing relative levels of miR-206 in L6 nucleoli, nucleoplasm, and cytoplasm during myogenesis. (B) Same as A, but a scrambled control probe was used for hybridization. Similarly sized regions in each compartment were circled, and the average intensity per pixel was recorded. The averages of these measurements in multiple cells are shown here. It should be noted that this experiment has a low signal-to-noise ratio compared with the other experiments presented in this article because it was necessary to use confluent cultures to induce differentiation. In situ hybridization signal is substantially reduced in confluent cell cultures because of permeability issues. Bars indicate standard errors.

These results demonstrated that the LNA probe hybridized as expected to miR-206 in the L6 myogenic cell culture system, but we wanted to further substantiate the specificity of miR-206 probe hybridization in the nucleolus. We considered it very unlikely that this localization pattern was due to cross-hybridization with other nucleolar RNAs because the results of BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST and www.psb.ugent.be/rRNA/blastrrna.html) and Ensembl (www.ensembl.org) searches showed that the miR-206 LNA probe is not complementary to any rat ribosomal RNAs (including 28S, 18S, 5.8S, or 5S sequences) or any known expressed small nucleolar RNAs. (These searches did locate an 11-nt complementary sequence in a U1 snRNA pseudogene with no upstream promoter sequences.) However, we also tested the fidelity of the hybridization directly with experiments in L6 myoblasts in which we varied the stringency of the hybridization and then compared the ratio of nucleolar to cytoplasmic signal present in digital images. Hybridization of LNA oligos has been shown to be affected by ionic strength and temperature in a manner similar to hybridization with standard phosphodiester backbone DNA oligos (19), so if there were differences in hybridization fidelity between the nucleolar and cytoplasmic targets, we would expect to see differences in the ratio under altered hybridization stringencies. However, we observed no significant difference in the nucleolus:cytoplasmic signal ratios when hybridization was carried out at twice the ionic strength (ratios were 1:1 at both 4× SSC and 2× SSC) or when a very high-stringency wash was included (nucleolar:cytoplasmic ratios were 1:1 after washes at 1× SSC and 0.1× SSC). These results indicate that the hybridization to the detected target in each of these compartments was equally specific. Therefore, it is highly likely that the LNA probe is hybridizing to bona fide miR-206 sequence in the nucleolus.

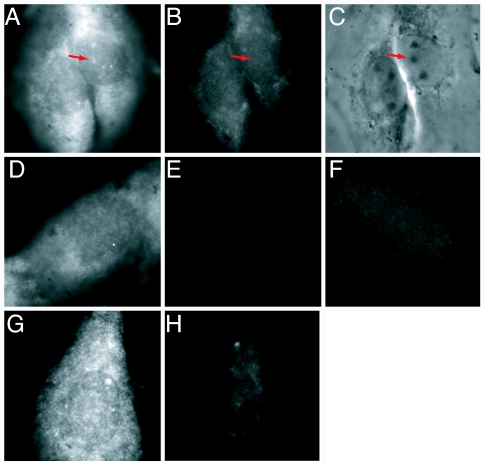

Although the foregoing results indicated that the LNA probe was indeed hybridizing to miR-206 RNA, we did not know whether we were detecting the mature and/or the precursor forms of this RNA (3, 14). We therefore designed a LNA probe to the loop region of the precursor hairpin of miR-206 (see Materials and Methods), which is expected to hybridize to both the primary transcript (pri-miR-206) and the immediate miR-206 precursor (pre-miR-206). This loop region of various pre-miRNAs, including pre-miR-206, has been shown to be preferentially available for hybridization in microarray assays (20). Fig. 3 shows the results of an experiment in which a probe complementary to mature miR-206, labeled with cy3 (Fig. 3A), and a second probe complementary to the loop region of the precursors of miR-206, labeled with fluorescein, (Fig. 3B) were simultaneously hybridized to L6 cells. The precursor-specific probe displayed very little signal (Fig. 3B) compared with the probe for mature miR-206 (Fig. 3A), and no specific signal was observed in the nucleolus. However, the cytoplasmic levels for the precursor probe were slightly above those obtained by using the scrambled control probe (Fig. 3F), especially in the perinuclear region. We conclude that the signal we observed in the nucleolus using the probe to the mature sequence is very likely to reflect hybridization to the mature form of miR-206.

Fig. 3.

Mature miR-206 probe hybridizes in a different pattern than a probe to premiR-206, and hybridization is RNase-sensitive. Dual color in situ hybridization was performed by using a cy3-labeled LNA probe to miR-206 (A) and a fluorescein-labeled LNA probe to premiR-206 (B). (C) Phase contrast image. Red arrows point to the nucleoli. (D and E) Control using cy3-labeled LNA miR-206 probe alone. (D) Red channel. (E) Green channel. This image shows a nucleus where the nucleolar:nucleoplasmic ratio of miR-206 is ≈1:1. (F) Cy3-labeled scrambled LNA probe. A, D, and F are scaled the same, and B and E are scaled the same. (G) Fixed cells were incubated with RNase buffer alone before in situ hybridization with cy3-labeled miR-206 LNA probe. (H) Cells were treated with a mixture of three ribonucleases (see Materials and Methods) before in situ hybridization with cy3-labeled miR-206 LNA probe. G and H are scaled the same. All images are 35 μm wide.

To confirm that the detected miR-206 signal indeed represented hybridization to RNA, we treated fixed cells with RNase before carrying out in situ hybridization with the miR-206 probe. Only low level of signal was observed in these cases (Fig. 3 G and H), indicating that the probe was hybridizing to RNA in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. When cells were treated with DNase before in situ hybridization with miR-206, the signal intensity and distribution remained unchanged (data not shown).

We next examined the nucleolar localization of miR-206 at higher spatial resolution. The nucleolus has been classically defined as having three components by ultrastructural criteria (21): the fibrillar centers (FCs), where the rDNA genes are located; the dense fibrillar component (DFC), which immediately surrounds the FCs and into which the prerRNA nascent transcripts extend and initial processing events take place; and the GC, where additional prerRNA processing and ribosome assembly take place. In addition to the classically identified ribosomal components, other proteins and RNAs that are not known to be linked to the ribosome assembly pathway have been detected in the nucleolus, including SRP RNA (15, 16), nucleostemin (22), telomerase components (23–25), and various cell cycle-related proteins (26, 27).

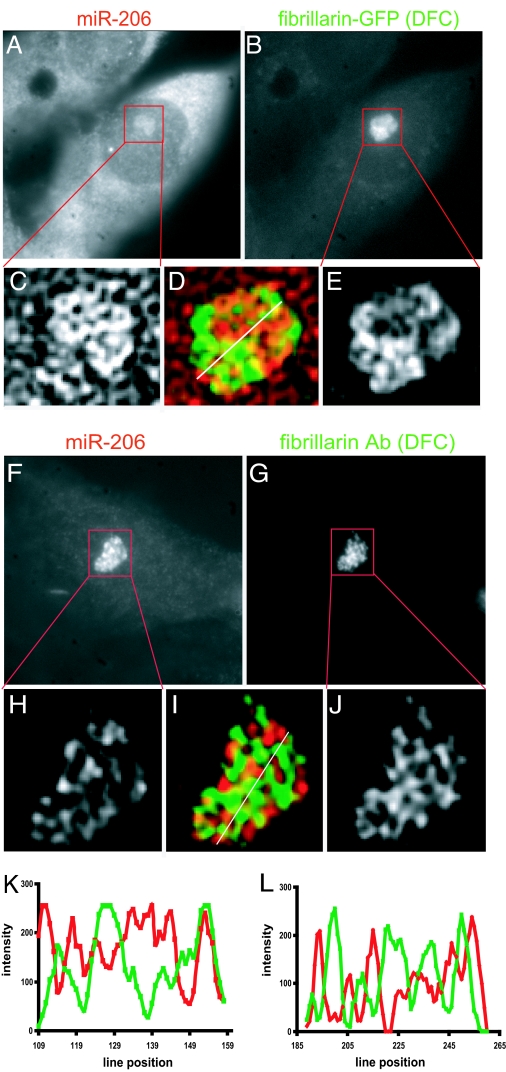

Fibrillarin, a protein complexed with small nucleolar RNAs involved in rRNA processing (28), is commonly used to demarcate the DFC. Fig. 4 shows the typical results of experiments in which L6 myoblasts were either transfected with plasmids coding for GFP-fibrillarin (Fig. 4 A–E and K) or immunostained with antibodies to fibrillarin (Fig. 4 F–J and L) and then subjected to in situ hybridization to detect miR-206. Fig. 4A shows the hybridization pattern for miR-206 after cells were transfected with GFP-fibrillarin and then fixed (Fig. 4B), and Fig. 4F shows the hybridization pattern for miR-206 after cells were fixed and then subjected to immunostaining for fibrillarin (Fig. 4G). Comparison of the miR-206 hybridization pattern in Fig. 4 A and F shows that, after cells have been immunostained and then subjected to in situ hybridization, much of the cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic miR-206 signal is lost, whereas the amount of nucleolar miR-206 signal stays the same or slightly increases as compared with results from the in situ hybridization after transfection with the GFP-fibrillarin plasmid. We believe that this is because the small miR-206 target molecules are washed out of the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm during the immunostaining procedure, because similar experiments with SRP LNA probes did not show reduced detection of the (15-fold) longer SRP RNA (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

miR-206 is not concentrated in nucleolar DFC. L6 myoblasts were transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP-fibrillarin (A–E) or subjected to immunostaining for fibrillarin (F–J) followed by in situ hybridization for miR-206, and image stacks were captured and subjected to 3D deconvolution. A and B show raw images of miR-206 and fibrillarin-GFP signal. C and E show the corresponding deconvolved nucleoli. D shows a pseudocolor image of C and E overlap where miR-206 is red and fibrillarin is green. Similarly, F and G show raw images of miR-206 and fibrillarin signal after antibody staining and in situ hybridization, H and J show the corresponding deconvolved nucleoli, and I shows a pseudocolor image of H and J overlap. Yellow indicates areas of minimal overlap between fibrillarin and miR-206. (K) Linescan showing intensity of both miR-206 (red) and fibrillarin-GFP (green) along the line shown in D. (L) Linescan showing intensity of both miR-206 (red) and antibody-detected fibrillarin (green) along the line shown in I. Images are 35 μm wide (A, B, F, and G), 5.7 μm wide (C–E), and 6.8 μm wide (H–L).

Images obtained after iterative deconvolution analysis (22, 29) of the intranucleolar distribution of miR-206 with respect to GFP-fibrillarin distribution are shown in Fig. 4 C–E, and similarly the results with fibrillarin antibody are shown in Fig. 4 H–J. Both detection methods revealed similar nucleolar distribution patterns, and it can be seen that there was very little overlap miR-206 (red) and fibrillarin (green) in either case. Fig. 4 K and L shows intensity linescans across the regions in Fig. 4 D and I, revealing the extent of miR-206 overlap with GFP-fibrillarin and fibrillarin antibody, respectively. These results show that miR-206 is not appreciably present in the DFC of the nucleolus.

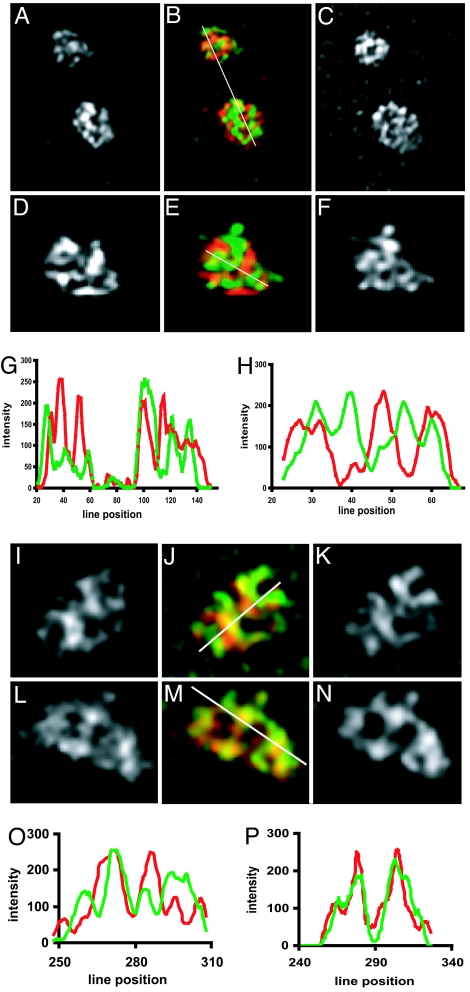

We then looked to see whether miR-206 was present in the FCs, using as a fiduciary marker the upstream binding factor (UBF), a protein that specifically binds the rDNA across the entire rDNA repeat (30). Fig. 5A–H shows two examples of nucleoli stained with UBF antibody (green) and hybridized with the miR-206 LNA probe (red), with the intensity linescans for the color overlays in Fig. 5 B and E shown in Fig. 5 G and H, respectively. Again, little overlap between UBF and miR-206 was observed.

Fig. 5.

miR-206 is not concentrated in nucleolar FCs but is concentrated in the GC. L6 myoblasts were subjected to immunostaining for UBF (to mark FCs, A–H) or nucleostemin (to mark the GC, I–P) followed by in situ hybridization to miR-206, and image stacks were captured and subjected to 3D deconvolution. Enlarged images of deconvolved nucleoli show miR-206 (A and D) and corresponding UBF (C and F) distribution, and pseudocolored images (B and E) show miR-206 (red) and UBF (green) overlap (yellow). Linescan in G corresponds to the line in B, and linescan in H corresponds to the line in E. Similarly, enlarged images of deconvolved nucleoli show miR-206 (I and L) and corresponding nucleostemin (K and N) distribution, and pseudocolored images (J and M) show miR-206 (red) and nucleostemin (green) overlap (yellow). Linescan in O corresponds to the line in J, and linescan in P corresponds to the line in N. Images are 9.9 μm wide (A–C), 5.9 μm wide (D–F), 7 μm wide (I–K), and 7.3 μm wide (L–N).

We next examined the localization of miR-206 within the GC by comparing its hybridization pattern to the distribution of nucleostemin within this compartment (Fig. 5 I–P). Our earlier work with nucleostemin has shown that this protein was a good marker for this region (22). Fig. 5 I–K and L–N show deconvolved midplanes from nucleoli of two different cells. Fig. 5 O and P shows intensity distributions along the lines depicted in the pseudocolored images in Fig. 5 J and M, respectively, and represent typical results. Linescans through some nucleolar regions showed virtually complete overlap (Fig. 5P) whereas others showed a much lesser degree of overlap (Fig. 5O), indicating that miR-206 partially, but not completely, overlaps with the regions of the GC occupied by nucleostemin. Taken together, these nucleolar mapping results demonstrate that the miR-206 is primarily localized to the GC.

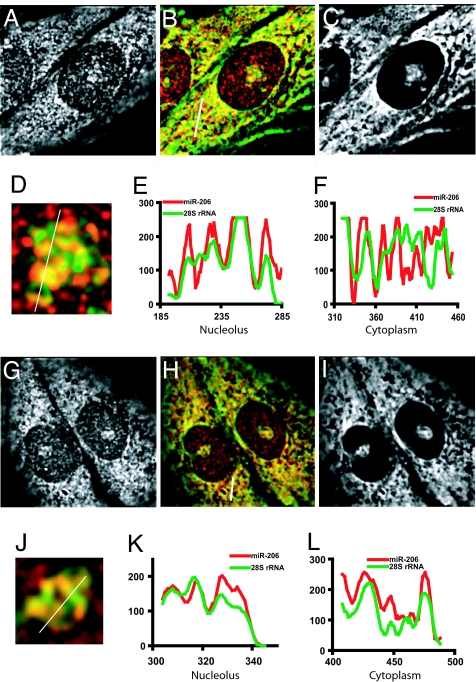

To learn more about the possible associations of miR-206 in the nucleolar GC, as well as the rest of the cell, we next compared the intracellular localization of miR-206 to that of 28S rRNA. We performed double in situ hybridization experiments to detect miR-206 and 28S rRNA and found that miR-206 colocalizes to a significant extent with 28S rRNA in both the nucleolus and the cytoplasm. Fig. 6 shows both whole-cell deconvolved images, and enlarged images of nucleoli, with accompanying linescans of the combined color-coded images. The yellow in the pseudocolored images (Fig. 6 B, D, H, and J), as well as the presence of overlapping maxima and minima in the linescans (even though not always the same intensity; Fig. 6 E, F, K, and L), demonstrate the substantial colocalization of these two probes. A significant overlap between miR-206 and 28S rRNA in both the nucleolus and the cytoplasm was observed in all cells, and in some regions the extent of spatial overlap was almost complete (e.g., Fig. 6K). These results demonstrate that miR-206 extensively colocalizes with 28S rRNA in both the cytoplasm and the GC of the nucleolus.

Fig. 6.

miR-206 partially colocalizes with 28S rRNA in the nucleolar GC and the cytoplasm. A–F and G–L depict results from two different cells. A and G show the miR-206 signal in a deconvolved mid-plane of the cell, and C and I show the 28S rRNA signal in the same plane. B and H are pseudocolored images combined to reveal overlap. D and J show enlarged images of the nucleoli. E and K are intensity linescans along the white line in D and J, respectively. F and L are intensity linescans along the white line in B and H, respectively. Images are 35 μm wide (A–C and G–I), 5.8 μm wide (D), and 4.1 μm wide (J).

Discussion

We have presented evidence that a miRNA involved in muscle development concentrates not only in the cytoplasm, but also in the nucleolus of cultured rat myogenic cells. Although nucleolar localization has not been reported for any other miRNA, it is too soon to know whether others visit the nucleolus because very little high-resolution work has been done in this relatively new field of miRNA cell biology. Indeed, while this manuscript was in preparation, endogenous siRNAs were reported to localize to the nucleolus in Arabidopsis (31), and there is evidence that microinjected siRNAs visit and sometimes concentrate in the nucleolus (32).

We found that miR-206 concentrates in the nucleolar GC, and not in the other two major compartments of the nucleolus, the FCs or the DFC. The GC is the region of the nucleolus where rRNA processing and ribosomal subunit assembly are completed and where a number of nonribosomal components, including nucleostemin, also concentrate (22, 33). Dual in situ hybridization in the present study showed that a substantial fraction of nucleolar miR-206 colocalizes with the 28S rRNA in the GC. Furthermore, a substantial portion of cytoplasmic miR-206 was observed to be colocalized with 28S rRNA. This cytoplasmic colocalization is consistent with the current hypothesis that miRNAs control gene expression by interfering with translation (1, 2, 4), and one recent study has suggested that at least some miRNAs may associate with polysomes (34) and thus directly interfere with translation at the elongation stage. Therefore, although an association of miR-206 with polysomes has yet to be examined in cell fractionation studies, our finding that miR-206 colocalizes with 28s rRNA in the cytoplasm suggests that it may be regulating target mRNAs in this way.

However, our discovery that the miR-206 is also localized in the nucleolus finds no obvious explanation in any previous or contemporary notions about miRNA biogenesis or function. As mentioned above, a recent study showed that endogenous siRNAs, which are closely related to miRNAs, localize to the nucleolus in Arabidopsis (31). It was proposed that siRNAs go to the nucleolus for modification and assembly, similar to other small RNAs that visit the nucleolus to be modified and/or assemble into RNP complexes (16, 35). At least some mammalian miRNAs are subject to A-to-I editing by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA (36, 37), and RNA editing enzymes have been found associated with the nucleolus in cultured mammalian cells (38). It has been proposed that adenosine deaminases that act on RNA compete with Drosha and thus regulate the processing of miRNAs in the nucleus (36, 39). It has also been shown that the 3′ terminal nucleotides of Arabidopsis miRNAs are subject to ribose-2′-O-methylation (40), but there are no reports so far of this modification in human miRNAs, much less any reports describing the intracellular compartment at which this might occur.

Although the above explanation for the nucleolar localization of miR-206 is reasonable, it does not explain why a substantial portion of miR-206 colocalizes with 28S rRNA in the nucleolus. It seems unlikely that miR-206 is involved in regulating transcription of the genes for rRNA because it did not colocalize with the known sites of these genes in the nucleolus, the FCs. This possibility was not trivial, because recent studies have implicated small noncoding RNAs, produced as intergenic transcripts within the rDNA repeats, in the transcription regulation of these genes (41). Furthermore, it is not likely that miR-206 is directly targeting rRNA transcripts in the way that miRNAs are predicted to target messenger RNAs, because we found no 7- or 8-nt sequence elements complementary to the 8-nt seed sequence of miR-206 in rat 28S, 5.8S, or 5S rRNAs. (The seed sequence is the region of miRNAs that is thought to hybridize most strongly to the target mRNA.) We did find one 18S site that contained 7/8 complementary nucleotides to the miR-206 seed sequence; however, there was very little (upstream) complementarity to the rest of miR-206. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that miR-206 hybridizes with different affinity to rRNA or associates with certain nascent ribosomal subunits through interactions other than hybridization to the rRNA.

A final intriguing possibility is that miR-206 could be targeting messenger RNAs that transit through the nucleolus, examples of which have been reported (42, 43), and perhaps miR-206 even moves with these messages to the cytoplasm. Certain proteins have been proposed to associate with messenger RNAs in the nucleolus and then move as a messenger ribonucleoprotein complex to the cytoplasm for translation (44), and it is possible that certain miRNAs may do the same. Of course, an experimental demonstration of the functional significance of the nucleolar concentration of miR-206 awaits further investigation.

Materials and Methods

In Situ Hybridization Probes.

LNA hybridization probes complementary to rat mature miR-206 and let-7a were purchased from Exiqon (Vedbaek, Denmark) with both 5′ and 3′ aminohexyl groups and labeled with cy3 as described (45). The miRNA sequences are given at http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk (46, 47). An LNA probe complementary to SRP RNA was designed to target nucleotides 228–248. Its sequence was 5′-Agg cgc gAt ccc Act acT gat-3′, where capital letters indicate the presence of a locked nucleotide. An LNA probe complementary to the loop region of rat premiR-206 (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk) (46, 47) was designed and had the sequence 5′-ttCcAtaGcGcaGtGaTatCta-3′. A control nonhybridizing LNA was designed with the sequence 5′-acgtgaCaCgttcgGagAatt-3′, as suggested by Faba Neumann and Jan Ellenberg (personal communication). These probes were also synthesized by Exiqon and labeled with either fluorescein or cy3 as described above. Fluorescein-labeled 28S rRNA probes (48) and the SRP peptide nucleic acid probe (15) were as described previously.

Cell Growth and Fixation.

L6 cells (from cultures that had been passaged <10 times) were plated on 25-mm coverslips in six-well tissue culture dishes in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Cells were cultured overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2, reaching a confluency of ≈50–60%. The coverslips were rinsed once with PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde/5 mM MgCl2 in PBS at 20–21°C for 15 min, and then stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C at least overnight and for up to 1 month. Alternatively, after overnight growth, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 2% horse serum, and the cells were allowed to differentiate and fuse into myotubes over 5–7 days and then fixed and stored as above.

In Situ Hybridization and Immunostaining.

Fixed cells were rehydrated in 5 mM MgCl2 in PBS and then prehybridized in 40% formamide in 2× SSC (1× SSC = 0.15 M NaC1/15 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0) for 10 min each at 20–21°C. Twenty nanograms of probe and 5 μg each of Escherichia coli tRNA and salmon sperm DNA (per coverslip) were heated at 94–95°C in 10 μl of 80% formamide in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water for 3–5 min, removed from the heating block, and immediately mixed with an equal volume of hybridization buffer (2 mg/ml BSA/20% dextran sulfate in 4× SSC) at 20–21°C. Twenty-microliter aliquots were placed on parafilm stretched on a glass plate, coverslips were inverted cell side down on the probe mixture, and hybridization was allowed to proceed at 37°C for 3 h. Coverslips were then washed for 10 min at 37°C with 40% formamide in 2× SSC, then twice for 30 min each at 37°C with 40% formamide in 1× SSC, and then at 20–21°C for 15 min once with 1× SSC and once for 15 min with 5 mM MgCl2 in PBS. Coverslips were then mounted in Prolong Gold Antifade (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and allowed to dry overnight in the dark at 20–21°C before observation and imaging. Immunostaining for UBF and fibrillarin and transfection of GFP-fibrillarin were performed as described (15), and after refixation the cells were subjected to in situ hybridization as described above. For RNase experiments, fixed cells were rehydrated, washed in RNase buffer (150 mM NaCl/1.5 mM MgCl2/10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5), and then incubated with RNase buffer alone or with RNases T2 (20 units), T1 (20 units), and A (0.5 units) in 20 μl per coverslip for 1 h at 37°C, followed by two 10-min washes with 5 mM MgCl2 in PBS at 20–21°C followed by the prehybridization wash and in situ hybridization as described above.

Microscopy and Image Processing.

Microscopy, image processing, and deconvolution analysis were as described (22, 49). A long-pass TRITC filter cube (Leica M2) was used to detect red fluorescence, and a band-pass “GFP” filter cube (Chroma 41017) was used to detect green fluorescence. All dual hybridization experiments were designed using the appropriate controls to ascertain that there was no bleed-through between the channels.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kevin Fogarty and Larry Lifshitz (Biomedical Imaging Facility, University of Massachusetts Medical School) for help with deconvolution analysis and Faba Neumann and Jan Ellenberg (European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, Germany) for suggesting the sequence for the nonhybridizing control probe. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-60551 and National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0445841.

Abbreviations

- miRNA

microRNA

- LNA

locked nucleic acid

- SRP

signal recognition particle

- FC

fibrillar center

- GC

granular component

- DFC

dense fibrillar component

- UBF

upstream binding factor.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Berezikov E, Plasterk RHA. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:R183–R190. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW. Cell. 2005;122:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamore PD, Haley B. Science. 2005;309:1519–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1111444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Parker R. Genes Dev. 2006;20:515–524. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattick JS, Macunin IV. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:R121–R132. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vester B, Wengel J. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13233–13241. doi: 10.1021/bi0485732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomsen R, Nielsen PS, Jensen TH. RNA. 2005;11:1745–1748. doi: 10.1261/rna.2139705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloosterman WP, Wienholds E, de Bruijn E, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RHA. Nat Methods. 2006;3:27–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokol NS, Ambros V. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2343–2354. doi: 10.1101/gad.1356105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J-F, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang D-Z. Nat Genet. 2006;38:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sempere LF, Freemantle S, Pitha-Rowe I, Moss E, Dmitrovsky E, Ambros V. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KK, Lee YS, Sivaprasad U, Malhotra A, Dutta A. J Cell Biol. 2006;17:4677–4687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullen BR. Mol Cell. 2004;16:861–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Politz JC, Lewandowski LB, Pederson T. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:411–418. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Politz JC, Yarovoi S, Kilroy SM, Gowda K, Zwieb C, Pederson T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:55–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawson MA, Purslow PP. Cells Tissues Organs. 2000;167:130–137. doi: 10.1159/000016776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao PK, Kumar RM, Farkhondeh M, Baskerville S, Lodish HF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8721–8726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602831103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.You Y, Moreira BG, Behlke MA, Owczarzy R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang J, Lee EJ, Gusev Y, Schmittgen TD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5394–5403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang S. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:739–741. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Politz JCR, Polena I, Trask I, Bazett-Jones DP, Pederson T. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3401–3410. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pederson T. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3871–3876. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.17.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong JM, Kusdra L, Collins K. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:731–736. doi: 10.1038/ncb846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y, Chen Y, Zhang C, Huang H, Weissman SM. Exp Cell Res. 2002;277:201–209. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung AK, Andersen JS, Mann M, Lamond AI. Biochem J. 2003;376:553–569. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coute Y, Burgess JA, Diaz JJ, Chichester C, Lisacek F, Greco A, Sanchez JC. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:215–234. doi: 10.1002/mas.20067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochs RL, Lischwe MA, Spohn WH, Busch H. Biol Cell. 1985;54:123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1768-322x.1985.tb00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrington WA, Lynch RM, Moore ED, Isenberg G, Fogarty KE, Fay FS. Science. 1995;268:1483–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.7770772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Sullivan AC, Sullivan GJ, McStay B. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:657–668. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.657-668.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pontes O, Li CF, Nunes PC, Haag J, Ream T, Vitins A, Jacobsen SE, Pikaard CS. Cell. 2006;126:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohrt T, Merkle D, Birkenfeld K, Echeverri CJ, Schwille P. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1369–1380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olson MO, Dundr M. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;123:203–216. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen CP, Bordeleau ME, Pelletier J, Sharp PA. Mol Cell. 2006;21:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu YT, Shu MD, Narayanan A, Terns MP, Steitz JA. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1279–1288. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luciano DJ, Mirsky H, Vendetti NJ, Maas S. RNA. 2004;10:1174–1177. doi: 10.1261/rna.7350304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blow MJ, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Enright AJ, Dicks E, Futreal PA, Wooster R, Stratton MR. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R27. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-r27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desterro JM, Keegan LP, Lafarga M, Berciano MT, O'Connell M, Carmo-Fonseca M. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1805–1818. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Connell MA, Keegan LP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:3–4. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu B, Yang Z, Li J, Minakhina S, Yang M, Padgett RW, Steward R, Chen X. Science. 2005;307:932–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1107130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayer C, Schmitz KM, Li J, Grummt I, Santoro R. Mol Cell. 2006;22:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bond VC, Wold B. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3221–3230. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michienzi A, Cagnon L, Bahner I, Rossi JJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8955–8960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidovic L, Bechara E, Gravel M, Jaglin XH, Tremblay S, Sik A, Bardoni B, Khandjian EW. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1525–1538. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Politz JC, Singer RH. Methods. 1999;18:281–285. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffiths-Jones S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D109–D111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D140–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Politz JCR, Tuft RA, Pederson T. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4805–4812. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobson MR, Pederson T. In: Analysis of mRNA Formation and Function. Richter JD, editor. New York: Academic; 1997. pp. 341–359. [Google Scholar]