Abstract

Neural stem cells and progenitors in the developing brain must choose between proliferation with renewal and differentiation. Defects in navigating this choice can result in malformations or cancers, but the genetic mechanisms that shape this choice are not fully understood. We show by positional cloning that the 30-zinc finger transcription factor Zfp423 (OAZ) is required for patterning the development of neuronal and glial precursors in the developing brain, particularly in midline structures. Mutation of Zfp423 results in loss of the corpus callosum, reduction of hippocampus, and a malformation of the cerebellum reminiscent of human Dandy–Walker patients. Within the cerebellum, Zfp423 is expressed in both ventricular and external germinal zones. Loss of Zfp423 results in diminished proliferation by granule cell precursors in the external germinal layer, especially near the midline, and abnormal differentiation and migration of ventricular zone-derived neurons and Bergmann glia.

Keywords: choroid plexus, Ebf1, nur12, Roaz, SMADs

Brain malformations in both human patients and experimental animals provide an important source of information about normal brain development as well as potential targets for clinical intervention. Many malformation disorders have a strong genetic basis, yet the genetic mechanisms are not fully understood. High-throughput chemical mutagenesis of the mouse has created a resource of single-gene alterations that may illuminate some of these mechanisms. Mutations that selectively affect the cerebellum are particularly tractable because of the relatively late development of the cerebellum and viability of cerebellar lesions.

Malformations affecting the cerebellar vermis are only poorly understood at the genetic level. Dandy–Walker malformations (DWM) are characterized by dilation of the fourth ventricle, anterior rotation of the cerebellum, vermis hypoplasia or agenesis, and hydrocephalus, and they may occur together with other abnormalities (1). Recent work identified a subset of DWM patients carrying interstitial deletions on chromosome 3, most of which were hemizygous for both ZIC1 and ZIC4 (2), transcription factors that promote proliferation of cerebellar granule cell precursors. Mice heterozygous for both Zic1 and Zic4 reproduce several DWM phenotypes, but show more modest effects on other characteristic features (2). Identifying genes with related phenotypes should help to clarify the developmental mechanisms behind such malformations.

The nur12 mouse was identified as having an ataxic gait and cerebellar hypoplasia, including agenesis of the vermis, in a large chemical mutagenesis screen (3). Here, we use positional cloning and noncomplementation with a gene trap allele to identify the Ebf- and SMAD-interacting 30 zinc-finger protein, Zfp423 (also known as ROAZ or OAZ) as the gene mutated in nur12 mice. Tsai and Reed (4, 5) first described ROAZ in rat olfactory tissue as an Ebf1 (previously OLF-1, or O/E-1)-interacting protein identified in a yeast two-hybrid assay. Based on the overlapping temporal sequence of Zfp423 and Ebf1 expression in olfactory precursors, they proposed that their interaction maintains olfactory precursors in an immature state, whereas release of Ebf to form homodimers promotes terminal differentiation. Subsequent genetic manipulations indicated that Ebf family members promote neuronal differentiation coupled to cell cycle exit and migration out of germinal zones (6–10). Our results show that Zfp423 is required for proliferation and differentiation by precursor cells in the developing brain. We propose that by forming mutually exclusive complexes with other transcription factors, Zfp423 sharpens the response of precursor cells to external differentiation signals. The phenotypic similarities between nur12 mutant cerebellum and DWM may shed further light on a group of human disorders for which few genetic clues have been found.

Results

Ataxia and Brain Malformations in nur12 Mice.

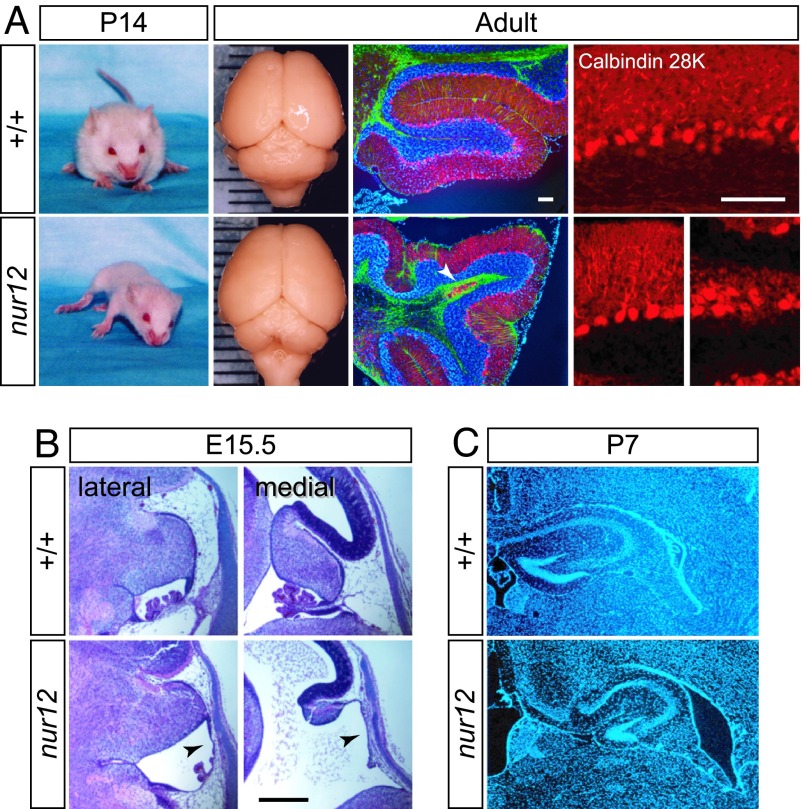

Homozygous nur12 mice have ataxia and tremor [see supporting information (SI) Movie 1] and have a malformation of the cerebellum that is more severe at the vermis than the hemispheres (Fig. 1A) and a pronounced anterior rotation of the cerebellum within the posterior fossa (Fig. 1B). These features are characteristic of certain human hindbrain malformations, including DWM and cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (CVH), but are not common among ataxic mouse mutations. Among intercross progeny, the nur12 cerebellum can range from complete loss of vermis with somewhat smaller hemispheres to almost complete loss of the cerebellum. Within the cerebellum of a single animal, regional cellular architecture may vary from essentially normal layers, with or without foliation, to regions of heterotopic Purkinje cells (arrowhead in Fig. 1A) or internalized parallel fiber tracts.

Fig. 1.

Ataxia and malformation in nur12 mutant mice. (A) P14 littermates photographed midstride illustrate severe ataxia and reduced weight gain by nur12 mutants. Surface view of littermate brains shows selective loss of the cerebellar vermis. (Grid lines: 1 mm.) Fluorescence micrographs with Calbindin (red), GFAP (green), and DAPI (blue) illustrate diminished foliation and heterotopic clusters of Purkinje cells (arrow). Higher-magnification image shows dendritic arborization in both aligned (Left) and heterotopic (Right) cells in nur12. (Scale bars: 100 μm.) (B) Sections through E15.5 embryos show midline-biased hypoplasia of cerebellum and choroid plexus. Note the anterior rotation of the cerebellum and distortion of the area membranacea superior (ams, arrowheads). (Scale bar: 500 μm.) (C) Dysgenesis of hippocampal formation and enlargement of the lateral ventricles of nur12 mutant compared with littermate control. Nuclear DAPI stain reveals pattern of cell bodies.

Developmentally, mutant embryos show dilation of the fourth ventricle and a modest rotation of the cerebellum relative to other structures as early as embryonic day (E)12.5. Severe hypoplasia of the presumptive vermis, with variable reduction in the hemispheres, is evident by E15.5 (Fig. 1B). Fourth ventricle choroid plexus is strikingly reduced and the anterior membrane segment (area membranacea superior), which connects the developing choroid plexus to the rhombic lip, remains juxtaposed to the roof plate of the hindbrain and becomes abnormally elongated (arrowheads in Fig. 1B).

Homozygous nur12 mutants also show defects in forebrain (Fig. 1C). In particular, the corpus callosum is absent, and the hippocampal formations are noticeably reduced and somewhat disorganized in nur12 animals compared with littermate controls. The lateral ventricles are enlarged in both embryos and adult.

Reduced Proliferation in Both Germinal Zones of nur12 Cerebellum.

To determine whether cerebellum hypoplasia in nur12 is primarily due to decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis, or both, we assayed DNA replication and markers of programmed cell death in staged embryos. Pregnant dams were injected with BrdU, and the number of cerebellar cells incorporating high levels after 1.5 h was determined by immunofluorescence for matched sections from nur12 and littermate controls. Mutant animals have significantly (and progressively) fewer BrdU+ cells than controls at E12.5, E14.5, and E15.5. By contrast, no significant difference is observed between genotypes in the number of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells at E14.5 (SI Fig. 7). Precursor cell populations, including Wnt1-expressing cells in the rhombic lip and isthmus organizer and Math1-expressing cells in the superficial layer of the cerebellar anlage appear grossly normal at E12.5, whereas Math1+ cells that form the external germinal layer (EGL) appear progressively reduced in number from E13.5 to E15.5 (SI Fig. 8).

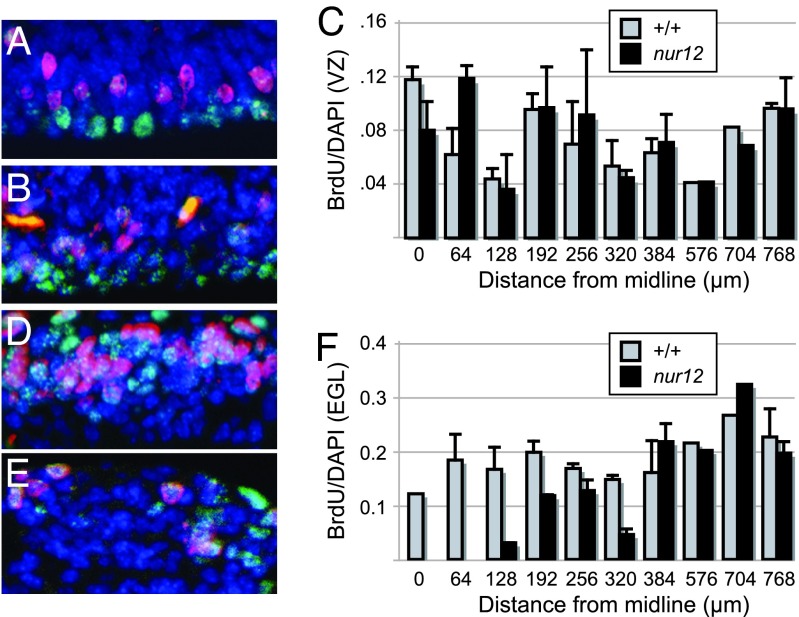

To examine each germinal zone in more detail, we counted mitotic cells (Ki67-positive), recently divided cells (BrdU), and total cell nuclei (DAPI) in sagittal sections from defined mediolateral positions at E12.5 and E14.5. In all, >170,000 cells were counted from five littermate pairs (Table 1). At E12.5, when most proliferation is in the ventricular zone (VZ), the number of cells counted for BrdU or DAPI is significantly reduced in nur12 (P < 0.01 for BrdU, P < 10−5 for DAPI; t test for Poisson counts). However, the proportion of mitotic cells (Ki67/DAPI) or cells in S phase (BrdU/DAPI) is not significantly reduced (P = 0.88 and P = 0.98, respectively; one-tailed Fisher's exact test), suggesting either fewer initial precursors or cumulative effects of a modest reduction in VZ proliferation. At E14.5, reductions in the ratios of both mitotic and S phase cells for the whole cerebellum are highly significant (P = 1.4 × 10−4 and P < 10−6, respectively). Analysis of each germinal zone as a function of distance from the midline shows that the most striking difference is the loss of S phase cells in the EGL near the midline (Fig. 2A–F), although the absolute number of proliferating cells is reduced in all mediolateral planes examined. The proportion of VZ cells entering S phase at E14.5 is marginally significant (P = 0.04).

Table 1.

Summary of proliferation markers across all mediolateral levels (+/+, nur12)

| Location | BrdU | P* | Ki67 | P* | DAPI | P* | BrdU/DAPI | P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E12.5 cerebellum | 2542, 2358 | 0.009 | 246, 239 | 0.75 | 17930, 15723 | <10−5 | 0.142, 0.150 | 0.98 |

| E14.5 cerebellum | 3507, 2437 | <10−5 | 4265, 3229 | <10−5 | 76091, 62554 | <10−5 | 0.046, 0.038 | <10−6 |

| VZ | 2107, 1916 | 0.001 | 2673, 2642 | 0.34 | 24308, 23314 | <10−5 | 0.087, 0.082 | 0.040 |

| EGL | 870, 242 | <10−5 | 894, 366 | <10−5 | 4534, 1550 | <10−5 | 0.192, 0.156 | 8.3 × 10−4 |

| Anterior rhombic lip | 461, 113 | <10−5 | 585, 172 | <10−5 | 2877, 901 | <10−5 | 0.160, 0.125 | 5.7 × 10−3 |

*P value, t test for Poisson counts, one-tailed for WT > nur12.

†Fisher's exact test, one-tailed for WT > nur12.

Fig. 2.

Reduced proliferation rate is biased toward the midline in EGL. Immunofluorescence and summary graphs illustrate proliferation rates along the mediolateral axis of ventricular zone (A–C) and external germinal zone (D–F) in nur12 and control littermates. BrdU incorporation (red) and Ki67 protein expression (green) are seen among DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) in ventricular zone [wild-type (A); nur12 (B)] and external germinal layer [wild-type (D); nur12 (E)]. Representative fields 192 μm from the midline at E14.5 are shown. Graphs show the ratio of BrdU-positive nuclei to DAPI-stained nuclei in ventricular zone (C) and external germinal layer (F) as a function of distance from the midline. Data are pooled counts from matched pairs of nur12/nur12 and +/+ littermates. Standard errors of the mean are indicated. No EGL was present in at least one nur12 animal for each point from 0 to 192 μm. Single pairs were counted at 576 and 704 μm.

Positional Cloning of nur12 Identifies a Null Allele of Zfp423.

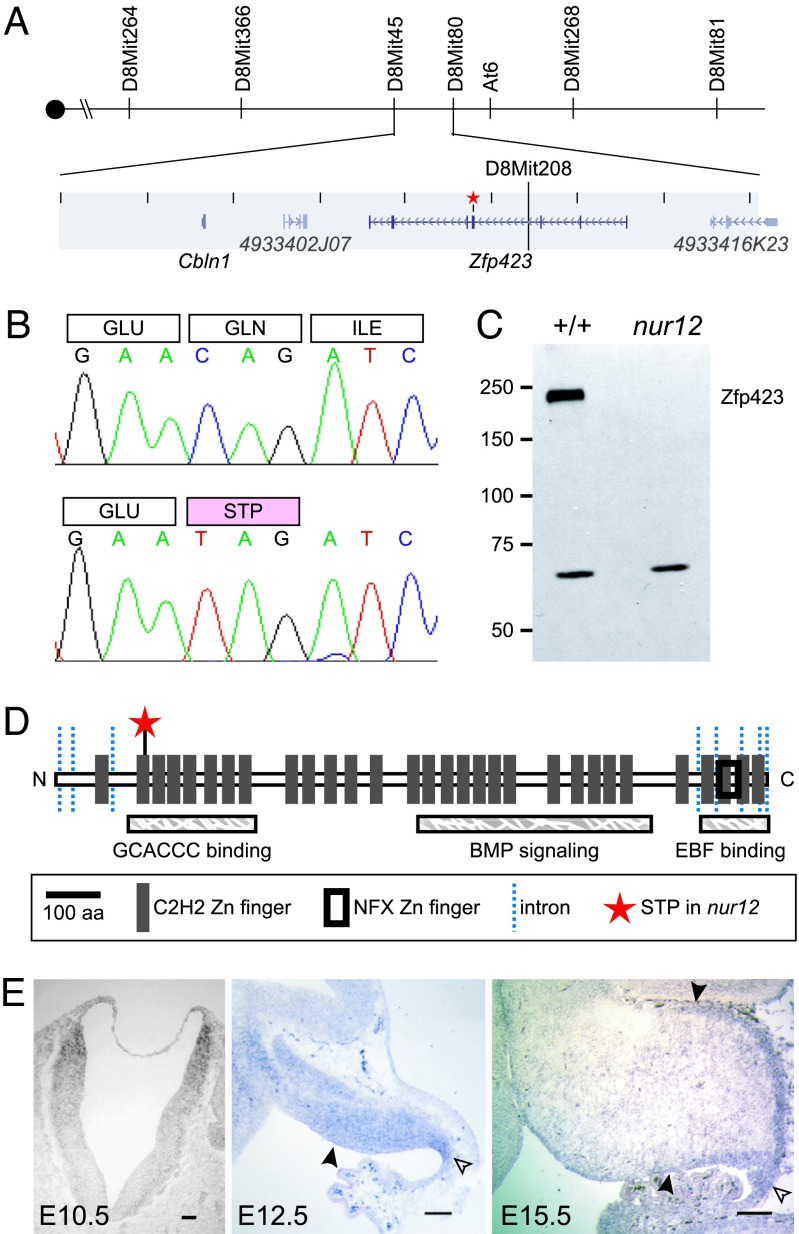

To identify the gene mutated in nur12, we mapped its position by recombination. We performed genome-wide homozygosity mapping on eight mutant animals from a nur12/+ × BALB/c intercross, using markers spaced ≈20 cM throughout the genome. This initial scan identified probable linkage to chromosome 8 (16/16 chromosomes sharing B6 genotype at D8Mit106). Genotypes for an additional 6 affected and 38 unaffected mice confirmed the localization of nur12 to an interval between D8Mit312 and D8Mit106. Fine-mapping through >1,000 more meioses identified a nonrecombinant interval of ≈810 kb (Fig. 3A), based on public sequence assembly (http://genome.ucsc.edu). This interval contains two known genes, Zfp423 and Cbln1, and two EST clusters.

Fig. 3.

nur12 is a null allele of Zfp423. (A) Recombination map for nur12. D8Mit45 is excluded by one and D8Mit80 by three recombination events. The nonrecombining interval contains Cbln1, Zfp423, and two ESTs. The star marks the site of the mutation. (B) Sequencing RT-PCR products from mutant and control identifies a nonsense mutation in Zfp423, at codon 166 of 1,292 with respect to RefSeq protein NP_201584. (C) Monoclonal antibody detects Zfp423 in neonatal brain extracts from +/+ but not nur12. A cross-reacting band of unknown origin is seen in both genotypes. (D) Zfp423 encodes 30 predicted C2H2 zinc-finger domains. Domains required for consensus site binding, BMP signaling, and EBF binding (13) are labeled. The star shows the nur12 stop codon; lines indicate exon junctions. (E) In situ hybridization shows Zfp423RNA expression in dorsal neural tube of the presumptive hindbrain by E10.5. At E12.5, Zfp423 is detected in the ventricular zone (filled arrowhead) of the cerebellar anlage and in the rhombic lip (open arrowhead). At E15.5, Zfp423 is detected in the remaining ventricular zone, rhombic lip, and EGL (upper arrowhead).

To identify mutations, we sequenced transcripts from all four positional candidate genes after RT-PCR from both mutant and control cerebellum. A nonsense mutation in the fourth exon of Zfp423 is specific to nur12 (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the calibrated mutation rate for the protocol that induced nur12 (11), this is the only polymorphism between nur12 and its parental strain (C57BL/6) observed among the positional candidate genes. Resequencing from genomic DNA confirmed that the mutation is unique to nur12. In addition, Cbln1-deficient mice have been recently reported with physiological, but no overt neuroanatomical, defects (12).

Zfp423 protein is not expressed in nur12. A monoclonal antibody against a C-terminal epitope of Zfp423 recognizes a protein of appropriate molecular weight in neonatal brain extracts from littermate control but not nur12 mice (Fig. 3C). Zfp423 normally encodes 30 Krüppel-like C2H2 zinc fingers (Fig. 3D). Zfp423 was first described as ROAZ, for rat Olf-1 (Ebf1)-associated zinc finger (5), and orthologous genes have also been referred to as ZNF423 in human, OAZ in frog (13), and Ebfaz in mouse (14). Three functional domains have been identified: a DNA-binding domain that recognizes the sequence GCACCCTTGGGTGC, a domain required for BMP signaling, and a C-terminal domain that interacts with Ebf1 (4, 5, 13). If the nur12 mutant transcript is translated, the resulting protein would terminate in the second zinc finger, losing all of the functionally annotated protein interaction and DNA-binding clusters.

To delimit where Zfp423 might act on cerebellum development, we examined its developmental expression by in situ hybridization (Fig. 3E). Expression is evident in both germinal zones of the developing cerebellum as well as other dividing cell populations. At E10.5, Zfp423 is expressed in the dorsal portion of hindbrain neural tube, and prominent expression in the rhombic lip is evident by E12.5. By E15.5, expression includes both the VZ and EGL. By postnatal day 2, Zfp423 expression in cerebellum is substantially reduced.

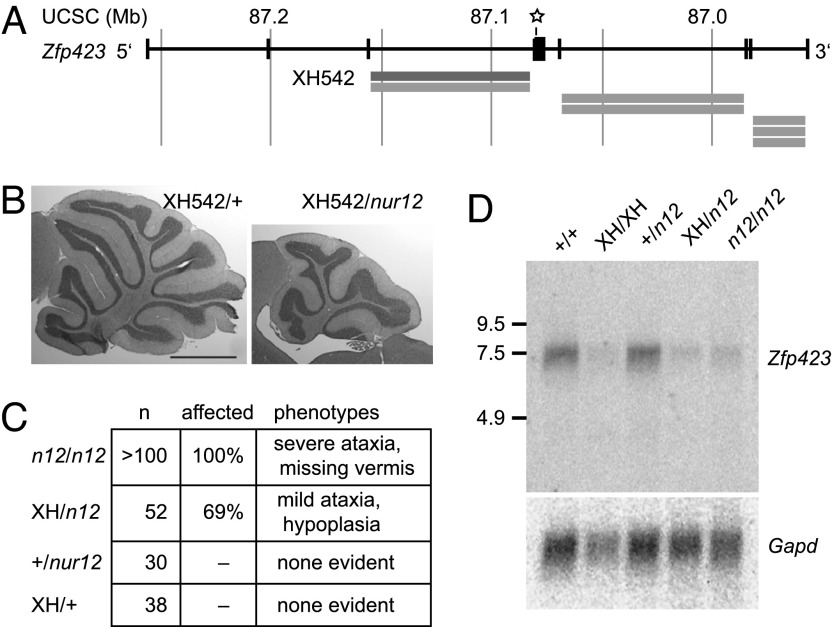

Reduction of Zfp423 Activity by a Weak Gene Trap Allele Causes Mild Hypoplasia.

We generated a second allele of Zfp423 from gene-trap ES cells (Fig. 4). ES cells containing a gene trap inserted into intron 3 of Zfp423 were obtained from the BayGenomics consortium (University of California, San Francisco, CA) (Fig. 4A) and injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. The resulting chimeras were then crossed to nur12 heterozygotes. XH542/nur12 progeny show mild cerebellar hypoplasia (Fig. 4B) and gait abnormalities (SI Movie 2) not seen in heterozygotes for either allele alone (Fig. 4C). Comparison to nur12 suggests that XH542 is a hypomorphic allele. Residual low-level expression of a full-length RNA indicates that this gene trap is also a partial loss-of-function allele at the molecular level (≤50% of +/+, Fig. 4D). RT-PCR sequencing confirms that the residual RNA is properly spliced at the exon 3–4 junction. Although the gene trap and nur12 alleles produce similar Zfp423 RNA levels, the residual gene trap RNA encodes full-length protein, whereas the nur12 nonsense transcript does not.

Fig. 4.

A hypomorphic Zfp423 gene trap allele does not complement nur12. (A) Schematic view of Zfp423 locus showing BayGenomics gene-trap cell lines. Orientation is reversed with respect to the chromosome to show Zfp423 5′ to 3′. Reported gene-trap integration sites (localized to introns by 5′ RACE) are indicated by gray bars. The star shows the location of stop codon in nur12. (B) Cross-sectional area of the vermis of XH542/nur12 is approximately half that of XH542/+ or +/+ controls. (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (C) Distribution of cerebellar phenotypes is indicated for each Zfp423 genotype. Ataxia and vermis agenesis are fully penetrant in nur12, although involvement of hemispheres is variable. Mild ataxia and cerebellar hypoplasia are seen in XH542/nur12 but not in either single heterozygote from the same cross. (D) Gene-trap mice have reduced expression of Zfp423. Northern blot of 7 μg of total RNA for animals of the indicated genotypes hybridized with Zfp423 cDNA fragment 3′ to the insertion site. Size markers are indicated in kilobases.

Zfp423 Alters the Pattern of Ebf1 Expression.

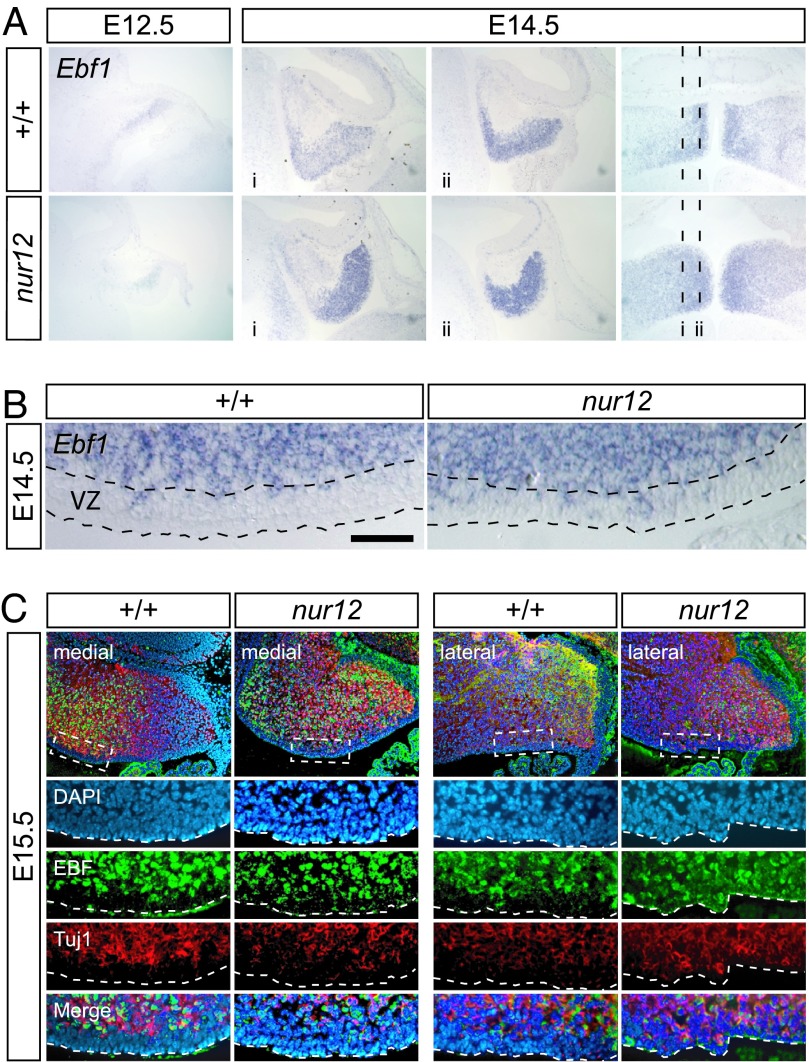

To determine whether Zfp423 impacts differentiation of cells in the ventricular zone, which expresses Zfp423 but has only modest reduction in proliferation, we analyzed cell type markers for VZ-derived neurons and glia (Fig. 5). Ebf1 is an early differentiation marker in several neuronal cell types, including Purkinje cells. Ebf1 promotes neuronal differentiation and cell cycle exit (8, 9) and is a dimerization partner of Zfp423 (5). Within the embryonic cerebellum, Ebf1 is selectively expressed in newly postmitotic VZ-derived neurons; however, the spatial pattern of Ebf1-expressing cells is broader and more diffuse in nur12 embryos (Fig. 5A). Strikingly, Ebf1-positive cells and cell clusters in the VZ are approximately twice as frequent in nur12 as in littermate controls (Fig. 5 B and C). Double-label immunofluorescence shows that early B cell factor (EBF)-positive cells in the VZ also express Tuj1, confirming that even the most superficial layer of the nur12 VZ contains cells that have acquired a neuronal identity (Fig. 5C). In contrast, Car8 (a later Purkinje cell marker that depends on RORα (15, 16), is seen only in the presumptive cerebellar cortex (SI Fig. 9), indicating that Ebf1-positive cells typically do migrate out of the VZ. However, heterotopic clusters of Purkinje cells in mutant adults (Fig. 1A and SI Fig. 9) do suggest deficits in cell migration.

Fig. 5.

Differentiation of ventricular zone neurons in nur12. (A) In situ hybridization shows Ebf1 expression in postmitotic neurons (presumptive Purkinje cells) in the cerebellum by E12.5. At E14.5, the mediolateral pattern of Ebf1 is both increased and more diffuse in nur12 than in control littermate. Approximate locations of sagittal sections are indicated on the horizontal section at right. (B) Ebf1-expressing cells in the ventricular zone (VZ) are approximately twice as frequent in nur12 than in littermate control; sagittal plane, posterior to the right. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (C) Immunofluorescence shows EBF, Tuj1 double-positive cells in the most superficial layer of the nur12 ventricular zone at E15.5, indicating neuronal identity of these cells, in both medial and lateral sections. The proportion of EBF+, Tuj1+ cells in VZ of nur12 is approximately twice that of wild type in both medial and lateral sections.

Zfp423 Is Required for Differentiation of Radial and Bergmann Glia.

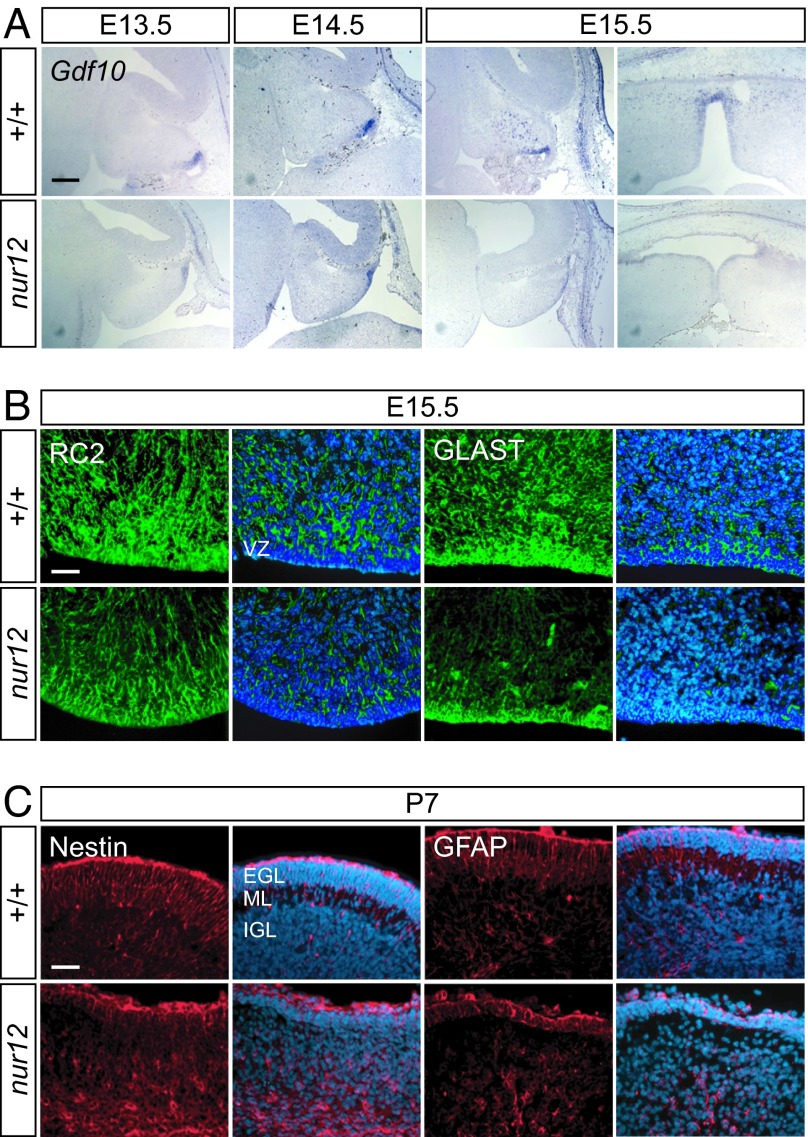

Bergmann glia are also born in the ventricular zone where they express lineage-restricted markers, including Gdf10, as early as E13.5. By E15.5, Gdf10-positive cells appear in the presumptive cerebellar cortex. In nur12, Gdf10 staining is reduced at the lateral edges of the E13.5-E15.5 cerebellum (Fig. 6A). More strikingly, Gdf10-positive cell bodies do not infiltrate the cerebellar cortex at E15.5 in nur12 mice, but instead remain in the posterior portion of the VZ, adjacent to the rhombic lip. Immunolabeling for RC2, an intermediate filament epitope in neuroepithelial and radial glial cells, shows that radial fibers do form, but at lower density than in controls (Fig. 6B). Labeling with GLAST (Slc1a3) confirms that the cell bodies remain more closely associated with the VZ in nur12 at E15.5, when they have migrated into the cortex in controls. GFAP and Nestin labeling at P7 show that this paucity and disorganization of glial fibers persists at later developmental stages (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Defects in Bergmann glial and neuroepithelial progenitor cells. (A) Gdf10, a marker for presumptive Bergmann glia, appears in ventricular zones of both nur12 and littermate controls by E13.5. At E14.5, expression is reduced in the hemispheres of the mutant. At E15.5, migrating Gdf10-positive cells are seen in the cerebellar cortex of the control but not the mutant in either sagittal (Left) or horizontal (Right) orientations. (Scale bar: 200 μm.) (B) Immunofluorescence shows fewer glial cell bodies and radial fibers in nur12. Both immature progenitors in the ventricular zone (VZ) and migrating glia express RC2 and GLAST. By E15.5, fewer marker-positive cells are seen in either VZ or presumptive cortex of nur12 compared with littermate control, although some radial fibers are evident. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (C) By P7, nestin- and GFAP-positive cells remain poorly organized in nur12, although end feet are clearly visible at the pial surface above the EGL. Merged images show nuclei stained by DAPI. VZ, ventricular zone; EGL, external granule layer; ML, molecular layer; IGL, internal granule layer. (Scale bar: 100 μm.)

Discussion

Zfp423 has been proposed to play a role in production of olfactory neurons (5, 17), oncogenic transformation of lymphocytes (14), and BMP-mediated dorsoventral axis patterning in amphibian embryos (13, 18). Here, we show by positional cloning that germ-line inactivation of Zfp423 results in malformation of the cerebellum, including agenesis of the vermis, through effects on both proliferation and differentiation of neural and glial precursor cells. Partial inactivation of Zfp423 through a hypomorphic gene trap allele has a less-severe effect on development and reduced penetrance in heteroallelic combinations, suggesting sensitivity of these phenotypes to Zfp423 level. Complementary studies on Zfp423 in olfactory precursors are reported by R. Reed (personal communication).

Zfp423-deficient mice show reduced levels of proliferation in both germinal zones, but particularly in the midline EGL. Both the number and proportion of proliferating cells are reduced in nur12, and the divergence between mutant and control embryos increases as development proceeds. This reduction correlates with a temporal shift in cell fate of Math1-positive precursors in the rhombic lip, from progenitors of hindbrain nuclei and some of the most anterior cerebellar granule cells at E10.5–E12.5 to predominantly granule cells at E13.5–E16.5 (20, 21).

Loss of Zfp423 also affects differentiation of ventricular zone-derived Purkinje neurons. Migration out of the proliferative zone is a common feature early in the differentiation program of immature neurons. The presence of EBF, Tuj1 double-positive cells in the VZ of Zfp423 mutant animals suggests a defect in migration, which may be secondary to an abnormal coupling of differentiation to cell cycle exit. The abnormal positioning of postmitotic Purkinje cells after leaving the VZ (Car8; SI Fig. 9) further suggests that the accuracy of migration or the timing of their differentiation with respect to migration is affected in nur12.

Radial glia are also reduced in number and retarded in maturation in nur12 embryos. Immature Bergmann glial cells express Gdf10 by E13.5 in the posterior VZ and retain expression through their migration and into adulthood. However, in nur12, expression of Gdf10 is reduced, and Gdf10-expressing cells do not invade the presumptive cortex at E15.5. Immunolabeling of intermediate filaments common to both neuroglial precursor cells and astroglia (RC2 and nestin) or elevated in astroglia (GFAP) confirms that radial glia in the nur12 cerebellum are reduced in number and delayed in their development (Fig. 6). Together with the increase in EBF+, Tuj1+ cells in the VZ, this suggests a defect in the timing of differentiation by neural stem cells or restricted precursors in Zfp423-deficient animals. The retardation of radial glial fibers may contribute to the aberrant morphology of the nur12 cerebellum by disrupting normal migration patterns of both VZ- and EGL-derived neurons.

Our data support a model in which Zfp423 and EBFs have both shared and opposing functions. Immature VZ cells express Zfp423, but not Ebf1 (Figs. 3E and 5B). EBF expression increases, whereas Zfp423 expression diminishes, during neuronal differentiation and maturation. At high concentration, Ebf1 is sufficient to drive neural progenitors out of the cell cycle, whereas dominant-negative Ebf1 blocks neuronal differentiation (9). In contrast, loss of Zfp423 appears to promote neural differentiation over proliferation and renewal. However, like EBFs, Zfp423 function appears to be required for proper differentiation. Building on the model of Tsai and Reed (5), we propose that before accumulation of EBF protein, Zfp423 promotes a progenitor cell fate. EBF expression alters transcriptional targets of Zfp423 through formation of EBF-Zfp423 heteromeric complexes. At higher EBF levels, EBF homodimers drive further differentiation. BMP-dependent formation of SMAD-Zfp423 complexes (or possibly complexes with other signal-dependent regulators), which are mutually exclusive with EBF-Zfp423 (13), should both act on unique target genes and shift Zfp423 away from EBF-containing complexes. An important prediction of this model is that Zfp423 sharpens the transition between proliferation and differentiation. In the absence of Zfp423, EBF should form functional homodimers earlier in the cell intrinsic program, with less dependence on external signals, driving a premature and likely atypical differentiation. This transcriptional network may be one mechanism for regulating cell-intrinsic timing events in neurogenesis (22). Identifying the intersections of these pathways on transcriptional control in neural progenitor cells will be important for understanding how these cells initiate their differentiation programs.

Selective vermis malformations have been reported in only a few previous genetic experiments, involving either proliferation signals from the midline (23, 24) or more limited anterior lobe defects due to transcriptional response in lineage-restricted granule cell precursors (2, 25). Although we also see reduced proliferation in Zfp423-expressing granule progenitors, this reduction could be secondary to reduced Shh signaling from immature Purkinje cells (26–28), which is functionally significant as early as E15.5 (15) and probably earlier. Our results provide direct evidence that Zfp423 is required for proliferation and differentiation by a subset of neuroglial progenitors, which has not been reported previously. Zfp423 has its strongest impact on the cerebellar vermis, where it is required by both germinal zones. Zfp423 is required for both proliferation and proper differentiation of neurons and radial glia, with selective genetic vulnerability at the midline. These results place Zfp423 and its transcriptional network as regulators of neural precursor cell proliferation and differentiation and therefore as candidate targets for human hindbrain malformations and potentially for pediatric brain cancers.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Genetic Typing.

nur12 was induced on C57BL/6 (B6) and held on a B6 × 129 hybrid background at the Mouse Mutagenesis Center for Developmental Defects (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX). The line was rederived onto BALB/c (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) at the University of California at San Diego Cancer Center Transgenic Mouse Core Facility after severe flooding in Houston had compromised the serological status of the stock. Mice reported here are thus on a mixed background, and each replicate experiment includes littermate controls. Simple sequence-length repeat markers (29) were selected from Massachusetts Institute of Technology Mouse Genetic and Physical Mapping project (www.broad.mit.edu/cgi-bin/mouse/index) for genetic mapping. Additional microsatellites identified from genomic sequence (http://genome.ucsc.edu) were developed for fine mapping. After positional cloning, nur12 was typed by allele-specific PCR or DNA sequencing of PCR products. Gene-trap insertions in 129/Ola-derived ES cells were obtained from BayGenomics (http://baygenomics.ucsf.edu). Injections into C57BL/6 blastocysts were performed at the University of California at San Diego Core Facility. Gene-trap alleles were typed by PCR for sequences unique to the insertion.

Sequencing.

RNA from mutant and control mice was isolated by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), converted into cDNA by using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), and amplified by PCR. DNA sequencing was performed as described (11).

BrdU Incorporation Assays.

Three hundred microliters of BrdU (5 mg/ml) was injected into each pregnant dam 1.5 h. before killing unless otherwise noted. Comparable results were obtained by fixation with either 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) or 10% formalin. Fixed embryos were equilibrated in 30% sucrose, embedded into a 1:1 mixture of optimal cutting temperature medium (TissueTek OCT; Sakura Finetek, Torrance CA): Aquamount (Lerner Laboratories, Pittsburgh, PA), frozen, and cut into 8-μm sections. Sections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, denatured in 2 M HCl, and then buffered with 0.1 M borate (pH 8.5). BrdU incorporation was visualized by immunofluorescence.

In Situ Hybridization and Immunofluorescence.

Embryos were fixed as above. Adults were perfused with buffered saline, followed by 4% PFA. Mutant and control littermate sections (8 or 16 μm) were mounted together on each slide. Slides were boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate and incubated with digoxygenin-labeled RNA probes overnight. Slides were washed and treated with RNase. Hybridized probe was detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxygenin antibody (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and BCIP/NBT substrate.

Antibodies.

For Western blot analysis, anti-Roaz (mouse monoclonal; BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) was used at 1:1,000 and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. Antibodies for immunolabeling were anti-Ki67 (rabbit polyclonal; Novocastra Vision BioSystems, Norwell, MA) at 1:100 dilution, anti-BrdU [mouse, clone G3G4 from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB; University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA)] at 1:20, anti-EBF (rabbit; gift of Randall Reed, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD) 1:200, anti-Tuj1 (mouse; Covance, Berkeley, CA) 1:200, RC2 and anti-Nestin (mouse, DSHB) 1:10, anti-GLAST [guinea pig; Chemicon, Temecula, CA; gift of Jean Christophe Deloulme (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Grenoble, France)], 1:8,000, and anti-GFAP (mouse; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) 1:100. Secondary antibodies used were from Molecular Probes; Eugene, OR; donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 at 1:750), Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA; goat anti-mouse IgM Cy2, 1:100), and Chemicon (goat anti-guinea pig Alexa Fluor 488 at 1:400).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Randall Reed for communicating results before publication and for anti-OLF-1 (EBF) antibody; and Moores University of California at San Diego (UCSD) Cancer Center Transgenic Mouse Shared Resource staff for embryo rederivation and blastocyst injections. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01 MH59207. W.A.A. and D.A.G. were supported in part by training funds from the NIH through the UCSD Genetics Training Program (T32 GM08666). E.R. was supported in part by a French Medical Research Foundation postdoctoral fellowship.

Abbreviations

- CVH

cerebellar vermis hypoplasia

- DWM

Dandy–Walker malformations

- En

embryonic day n

- EBF

early B cell factor

- EGL

external germinal layer

- VZ

ventricular zone.

Note.

While this work was under review, a preliminary report confirmed the gross cerebellar defect of Zfp423 knockout mice (19).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0609184103/DC1.

References

- 1.ten Donkelaar HJ, Lammens M, Wesseling P, Thijssen HO, Renier WO. J Neurol. 2003;250:1025–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-0199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grinberg I, Northrup H, Ardinger H, Prasad C, Dobyns WB, Millen KJ. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1053–1055. doi: 10.1038/ng1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kile BT, Hentges KE, Clark AT, Nakamura H, Salinger AP, Liu B, Box N, Stockton DW, Johnson RL, Behringer RR, et al. Nature. 2003;425:81–86. doi: 10.1038/nature01865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai RY, Reed RR. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6447–6456. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai RY, Reed RR. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4159–4169. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04159.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang SS, Lewcock JW, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P, Reed RR. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2004;131:1377–1388. doi: 10.1242/dev.01009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corradi A, Croci L, Broccoli V, Zecchini S, Previtali S, Wurst W, Amadio S, Maggi R, Quattrini A, Consalez GG. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2003;130:401–410. doi: 10.1242/dev.00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garel S, Marin F, Grosschedl R, Charnay P. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:5285–5294. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Dominguez M, Poquet C, Garel S, Charnay P. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2003;130:6013–6025. doi: 10.1242/dev.00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croci L, Chung SH, Masserdotti G, Gianola S, Bizzoca A, Gennarini G, Corradi A, Rossi F, Hawkes R, Consalez GG. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2006;133:2719–2729. doi: 10.1242/dev.02437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Concepcion D, Seburn KL, Wen G, Frankel WN, Hamilton BA. Genetics. 2004;168:953–959. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.029843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirai H, Pang Z, Bao D, Miyazaki T, Li L, Miura E, Parris J, Rong Y, Watanabe M, Yuzaki M, Morgan JI. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/nn1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hata A, Seoane J, Lagna G, Montalvo E, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Massague J. Cell. 2000;100:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81561-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warming S, Suzuki T, Yamaguchi TP, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Oncogene. 2004;23:2727–2731. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold DA, Baek SH, Schork NJ, Rose DW, Larsen DD, Sachs BD, Rosenfeld MG, Hamilton BA. Neuron. 2003;40:1119–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00769-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold DA, Gent PM, Hamilton BA. Brain Res. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.080. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang SS, Tsai RY, Reed RR. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4149–4158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04149.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ku M, Howard S, Ni W, Lagna G, Hata A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5277–5287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warming S, Rachel RA, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6913–6922. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02255-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sgaier SK, Millet S, Villanueva MP, Berenshteyn F, Song C, Joyner AL. Neuron. 2005;45:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machold R, Fishell G. Neuron. 2005;48:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen Q, Wang Y, Dimos JT, Fasano CA, Phoenix TN, Lemischka IR, Ivanova NB, Stifani S, Morrisey EE, Temple S. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:743–751. doi: 10.1038/nn1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J, Liu Z, Ornitz DM. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:1833–1843. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.9.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trokovic R, Trokovic N, Hernesniemi S, Pirvola U, Vogt Weisenhorn DM, Rossant J, McMahon AP, Wurst W, Partanen J. EMBO J. 2003;22:1811–1823. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aruga J, Tohmonda T, Homma S, Mikoshiba K. Dev Biol. 2002;244:329–341. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahmane N, Ruiz-i-Altaba A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:3089–3100. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallace VA. Curr Biol. 1999;9:445–448. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wechsler-Reya RJ, Scott MP. Neuron. 1999;22:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietrich WF, Miller J, Steen R, Merchant MA, Damron-Boles D, Husain Z, Dredge R, Daly MJ, Ingalls KA, O'Connor TJ. Nature. 1996;380:149–152. doi: 10.1038/380149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.