Abstract

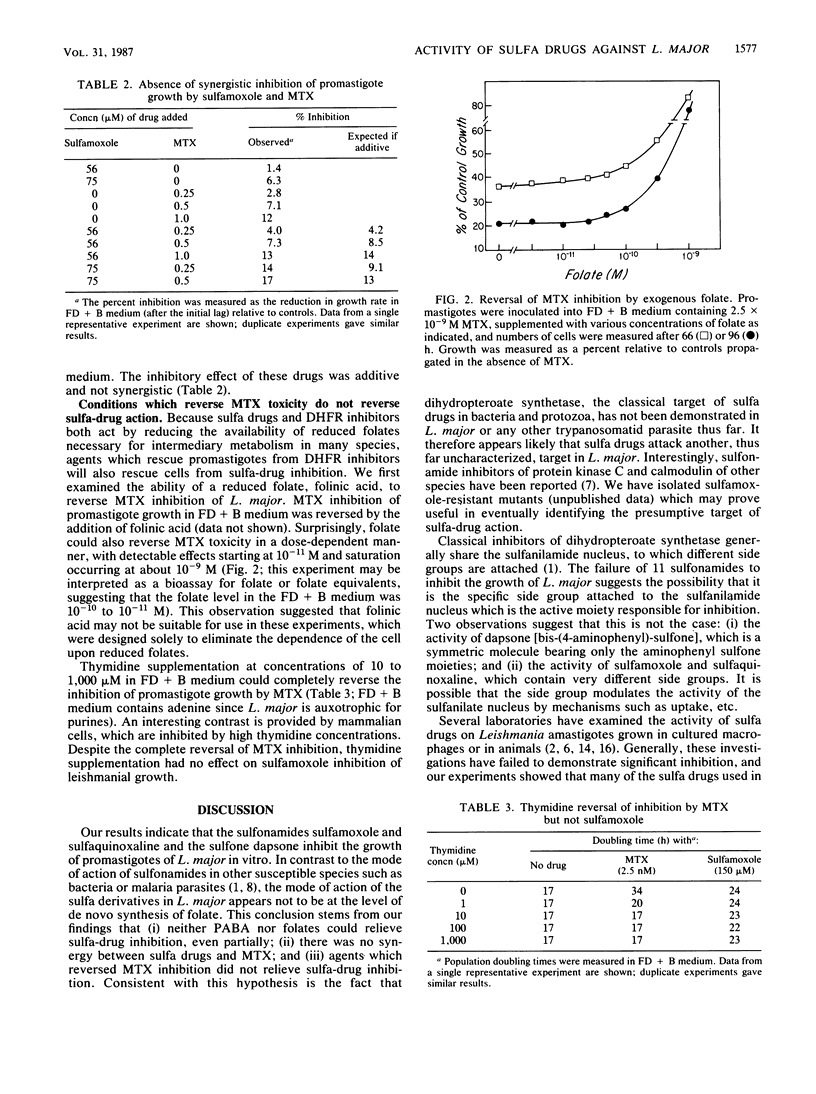

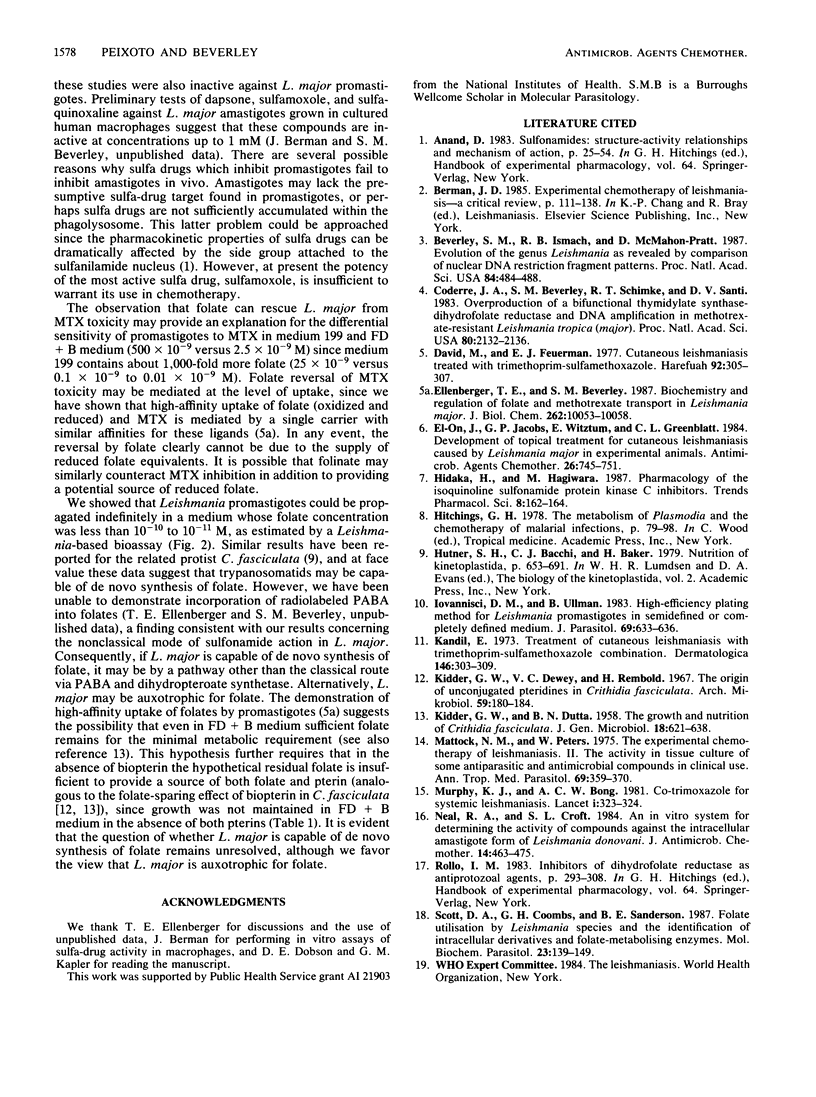

We examined the susceptibility of promastigotes of Leishmania major to sulfonamides and sulfones in vitro. In a completely defined medium only sulfamoxole, sulfaquinoxaline, and dapsone were inhibitory; the concentrations required for 50% inhibition of the rate of growth were 150, 600, and 600 microM, respectively. Eleven other sulfa drugs were ineffective at concentrations up to 2 mM. The growth inhibition was similar to that observed in procaryotes: the cells continued logarithmic growth for several cell doublings before inhibition was observed. Surprisingly, the addition of p-aminobenzoate or folate did not reverse the effects of the active sulfa drugs, the effects of sulfamoxole and methotrexate were additive rather than synergistic, and the addition of thymidine reversed methotrexate but not sulfa-drug inhibition. These results suggest that the mode of action of sulfa drugs on L. major is not by the classical route of inhibition of de novo folate synthesis. Promastigotes could be propagated for more than 40 passages in a completely defined medium in which the only added pterin was biopterin. The folate concentration in this medium was less than 10(-10) to 10(-11) M, as determined by a Leishmania bioassay. Although these data suggest that L. major may be capable of de novo synthesis of folate, the nonclassical mode of action of sulfa drugs, as well as other studies, favors the view that L. major is auxotrophic for folate.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beverley S. M., Ismach R. B., Pratt D. M. Evolution of the genus Leishmania as revealed by comparisons of nuclear DNA restriction fragment patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Jan;84(2):484–488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coderre J. A., Beverley S. M., Schimke R. T., Santi D. V. Overproduction of a bifunctional thymidylate synthetase-dihydrofolate reductase and DNA amplification in methotrexate-resistant Leishmania tropica. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Apr;80(8):2132–2136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David M., Feuerman E. J. [Cutaneous leishmaniasis treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxasol]. Harefuah. 1977 Apr 1;92(7):305–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-On J., Jacobs G. P., Witztum E., Greenblatt C. L. Development of topical treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major in experimental animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984 Nov;26(5):745–751. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.5.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberger T. E., Beverley S. M. Biochemistry and regulation of folate and methotrexate transport in Leishmania major. J Biol Chem. 1987 Jul 25;262(21):10053–10058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovannisci D. M., Ullman B. High efficiency plating method for Leishmania promastigotes in semidefined or completely-defined medium. J Parasitol. 1983 Aug;69(4):633–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIDDER G. W., DUTTA B. N. The growth and nutrition of Crithidia fasciculata. J Gen Microbiol. 1958 Jun;18(3):621–638. doi: 10.1099/00221287-18-3-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandil E. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole combination. Dermatologica. 1973;146(5):303–309. doi: 10.1159/000251981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder G. W., Dewey V. C., Rembold H. The origin of unconjugated pteridines in Crithidia fasciculata. Arch Mikrobiol. 1967;59(1):180–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00406330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattock N. M., Peters W. The experimental chemotherapy of leishmaniasis. II. The activity in tissue culture of some antiparasitic and antimicrobial compounds in clinical use. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1975 Sep;69(3):359–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K. J., Bong A. C. Co-trimoxazole for systemic leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1981 Feb 7;1(8215):323–324. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal R. A., Croft S. L. An in-vitro system for determining the activity of compounds against the intracellular amastigote form of Leishmania donovani. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984 Nov;14(5):463–475. doi: 10.1093/jac/14.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. A., Coombs G. H., Sanderson B. E. Folate utilisation by Leishmania species and the identification of intracellular derivatives and folate-metabolising enzymes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987 Mar;23(2):139–149. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]