Abstract

Postabortion care providers who breach patient confidentiality endanger women’s health and violate ethics. A 1998 abortion ban in El Salvador likely spurred an increase in the number of women investigated, because many women were reported to legal authorities by health care providers.

Having analyzed safeguards of confidentiality in laws and ethical guidelines, we obtained information from legal records on women prosecuted from 1998 to 2003 and identified factors that may lead to reporting through a survey of obstetrician-gynecologists (n=110).

Although ethical and human rights standards oblige providers to respect patients’ privacy, 80% of obstetrician-gynecologists mistakenly believed reporting was required. Most respondents (86%) knew that women delay seeking care because of fear of prosecution, yet a majority (56%) participated in notification of legal authorities.

POLICIES OR LAWS THAT compel providers to report suspected unlawful abortions “are ethically offensive and may be challenged, but cannot be ignored.”1(p381) In El Salvador, however, the collaboration of health care providers and legal authorities in the identification and prosecution of women for formally unlawful abortion has not been challenged by the presiding magistrates, legal scholars, or health and rights advocates. A 1999 study by the Center for Reproductive Rights found that the number of women prosecuted for illegal abortion doubled after a 1998 law was passed criminalizing all forms of intentional abortion—including an abortion to save the woman’s life. One half of the women prosecuted were reported to the legal authorities by their post-abortion care providers.2

The Center for Reproductive Rights study identified an important shift in practice following the abortion ban whereby public health workers began implicating women seeking postabortion care by notifying public prosecutors and police when they suspected that their patient had undergone an unlawful abortion. According to this study, this practice may have begun after a notice was circulated to all public hospitals by the National Secretariat of the Family informing health care workers of an alleged legal obligation to report unlawful abortion.2(p104)

Health care workers who report postabortion patients to legal authorities may contribute to abortion-related morbidity and mortality by deterring women who fear prosecution from seeking lifesaving care.3 Women who do seek treatment after abortion may be reluctant to disclose the reason they need medical care, thus compromising providers’ ability to promptly diagnose and treat their patients. Although there are no reliable data on the incidence of unlawful abortions in El Salvador, a review of the national population-based reproductive health surveys from 1993,4 1998,5 and 20036 suggested that the self-reported incidence of abortion remained unchanged during that period. However, the proportion of Salvadoran women who reported receiving treatment for severe abortion complications (blood transfusions) doubled between 1998 and 2003.5,6 These data suggest that abortion-related morbidity may have increased after the law change went into effect.

Confidentiality and Abortion in El Salvador

In notifying legal authorities of suspected abortion, health care providers disclose confidential information about their patients. In Salvadoran ethical and legal codes, confidentiality is defined as “professional (or medical) secrecy.” According to the 1986 Salvadoran Medical College’s Code of Medical Ethics (Ethics Code),

The preservation of medical secrecy is a fundamental duty of the health care professional. The public interest, the security of the sick, the honor of the family, the respect of the health care profession and the dignity of persons depend on the preservation of professional secrecy which requires health care professionals to keep secret what they see, hear or discover in the context of their professional role.7

Ethical Obligations

The Ethics Code further states that confidentiality of patient information is implicit and does not need to be articulated before the patient receives care. By preserving confidentiality, providers respect patients’ autonomy, abide by their obligation to reciprocate patients’ trust, and preserve public confidence in the provider–patient relationship.8 Patients who trust their providers to safeguard their secrets are more likely to seek prompt care for stigmatized health conditions and to reveal sensitive information essential for proper diagnosis and treatment.

The ethical duty to safeguard confidentiality is also mandated by laws that protect individuals’ right to privacy. Privacy, in the context of health care services, is the personal right “to control information [about oneself] that others possess.”9(p19) Confidentiality is “the duty of those who receive private information not to disclose it without the patient’s consent.”9(p20) Thus, patient–provider confidentiality is protected by laws as a mechanism through which the right to privacy is fulfilled.

Legal Obligations

The Salvadoran health and penal codes provide the same definition and conditions for professional secrecy as described in the Ethics Code and penalize the violation of patient confidentiality with suspension of medical license and imprisonment for up to 2 years.10(art37,38),11(art187)

The Salvadoran government is a party to the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, human rights treaties that have been interpreted to explicitly protect the right to privacy and confidentiality in postabortion health care services.12,13 The United Nations–appointed Human Rights Committee, which monitors states’ progress in the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, has declared that “states may fail to protect women’s privacy . . . where [they] impose a legal duty upon doctors and other health personnel to report cases of women who have undergone abortion.”14(p133) According to the Salvadoran constitution, these treaty obligations constitute binding laws at the national level and, in the case of discrepancy, take precedence over national law.15(art144)

Although Salvadoran and international law seem to coincide in favor of preserving postabortion patients’ confidentiality, the Salvadoran ethics7(art59) and health codes9(art38) do allow confidential information to be disclosed when (1) authorized by the patient, (2) required by law, (3) provided as sworn testimony as an expert witness, or (4) provided as notification to public health authorities of infectious disease. The critical question of whether providers have a legal duty to report suspected abortions is susceptible to misinterpretation because of nuanced and contradictory requirements stipulated in 3 separate statutory codes.

Salvadoran law does not explicitly state that providers must report suspected abortion, and we were unable to identify any national jurisprudence on this issue. However, health care workers are obliged to report injuries that result from criminal acts perpetrated against their patients.16(art312) Because abortion is a “criminal act,” this requirement could be construed to mean that providers are obliged to report unlawful abortion. However, the Code of Penal Process, which defines the procedures and conditions for the implementation of the provisions of the Penal Code, stipulates that health care workers are not obliged to report confidential information17(art232) and further establishes that information acquired through unlawful breach of confidentiality is invalid for legal purposes.18(art187)

Together, the laws make a circular argument wherein (1) the Health Code stipulates that confidential information may be disclosed if required by law, (2) the Penal Code obliges providers to report suspected crimes, and (3) the Penal Process Code states that providers are exempt from reporting information protected by the covenant of professional secrecy.

Given this complex legal framework, we aimed to study the prosecution of women for unlawful abortion and the operationalization of laws and ethical guidelines that safeguard confidentiality by public health workers in El Salvador. Further we sought to (1) describe the number of women prosecuted for unlawful abortion in El Salvador from 1998 to 2003, (2) assess providers’ knowledge of confidentiality laws and their involvement in and the factors influencing the reporting of suspected abortion, and (3) assess available evidence of the impact of this practice on women’s care-seeking behavior.

METHODS

To document the number of women charged with unlawful abortion, we obtained permission from the Office of the Public Prosecutor of the Republic of El Salvador to review national statistics on criminal investigations of unlawful abortion between 2000 and 2003. The public prosecutor’s office includes 18 regional and subregional affiliates who are responsible for initiating criminal investigations and bringing criminal proceedings before a justice of the peace. Once the criminal proceeding is brought before the court, legal records are housed in the courthouse where the case is processed. Cases are initially brought before a justice of the peace, then proceed to an examining magistrate, and then by a sentencing court.

We reviewed all records of abortion cases from a convenience sample of 100 (31%) of the 322 courts of justices of the peace, 22 (47%) of the 46 courts of the examining magistrate, and 6 (29%) of 21 sentencing courts in El Salvador. We abstracted sociodemographic information (education, age, marital status, and employment type), informant (health care institution vs other), abortion method, and type of defense (public vs private) from the records of women who were prosecuted (women whose cases were brought before the court) for unlawful abortion since January 2000.

To explore provider perspectives on reporting, we surveyed members of the Salvadoran Association of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstetrician-gynecologists play a central role in the provision of postabortion care because they are the only type of provider authorized to perform uterine evacuations for incomplete abortion.19 The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of El Salvador medical school, and the instrument was pretested.

A systematic random sample of 110 obstetrician-gynecologists was drawn from the Association of Obstetrics and Gynecology membership list (n = 344). Data were collected from November 2003 through March 2004, and the response rate for the questionnaire was 100%. Researchers made personal appointments with study participants to solicit verbal informed consent and deliver and retrieve the self-administered questionnaire. The survey instrument was an anonymous questionnaire that included 15 closed and 5 open-ended items.

Data were collected on respondents’ age range, gender, religion, years of practice, knowledge of international and national law on patient–provider confidentiality, and perceived prevalence of, personal involvement with, motivations for, and consequences of reporting unlawful abortion. For open-ended questions, core categories in the responses were first identified; surveys were then coded serially by 2 researchers. We used logistic regression to identify variables associated with involvement in the behavior of interest, which was reporting suspected abortion. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 10.1.1 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) and SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Women Charged With Unlawful Abortion 2000–2003

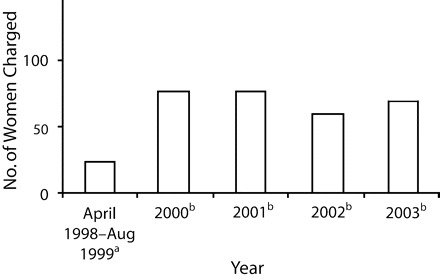

The number of women charged with unlawful abortion rose after the abortion law was changed in April 1998. Figure 1 ▶ presents the total annual number of indictments against women according to public prosecutor’s records for a 16-month period following the law change in April 1998 (reported by the Center for Reproductive Rights)2(p7) alongside the total annual number of charges placed against women for unlawful abortion between 2000 and 2003. A total of 283 criminal investigations were initiated against women charged with unlawful abortion over the study period. We were able to identify legal records for 32 women whose cases were brought before the court by the public prosecutor’s office over this time period, suggesting that many cases sit in legal limbo or are dismissed. All 32 women were charged with consenting to and practicing an unlawful abortion under Article 133, Chapter II (Crimes Against the Life of Human Beings in the Beginning Stages of Development) of the Penal Code, which carries a jail sentence of 2 to 8 years.

FIGURE 1—

Women charged with unlawful abortion in El Salvador, 1998–2003.

aSource: Center for Reproductive Rights (2000).2

bSource: Office of the Public Prosecutor for the Republic of El Salvador (Fiscalia General de la Republica de El Salvador), Statistics Unit, Abortion Cases: 2000–2003.

Although many of the records were incomplete, we were able to determine that the women ranged in age from 18 to 36 years and held poorly remunerated occupations including homemaker,12 student,6 housekeeper,4 and market vendor.3 Of the 13 files in which the accuser was identified, 11 were public health care institutions and 2 were relatives of the woman. Alleged methods of abortion included insertion of a metal rod or catheter,9 use of prostaglandins,4 ingestion of medicinal plants,1 and ingestion of poison.2 Of the 17 files in which the defendant’s legal counsel was identified, all were public defenders. By the conclusion of the study, 1 of the women charged in 2003 had been sentenced.21

Obstetrician-Gynecologists and Reporting Suspected Abortion

Of the 110 providers recruited for the study, 53% were women, 79% were employed by public health institutions, and 61% reported having practiced medicine for more than 5 years (and thus were in practice before the law change). The majority of obstetrician-gynecologists surveyed (80%) believed they were legally required to report unlawful abortion. Only 23% were aware that Salvadoran law protects and in fact obligates patient–provider confidentiality. More than one third (38%) were cognizant of international legal protections for confidentiality. However, most (68%) believed that confidentiality laws could protect providers who did not report their patients and that it was ethical to not report unlawful abortion (69%).

Involvement in Reporting

More than half (56%) of respondents reported that they had been involved in notifying legal authorities about a suspected unlawful abortion. The odds that a respondent had been involved in reporting an unlawful abortion were higher among respondents who worked in the public sector (P < .01) and among those who were not aware that international law protects patient–provider privacy and confidentiality (P < .001) (Table 1 ▶).

TABLE 1—

Demographic Characteristics, Knowledge, Beliefs, and Odds Ratios (ORs) of Salvadoran Obstetrician-Gynecologists Involved in Reporting Abortions (n = 110): November 2003 Through March 2004

| Total No. (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 58 (53) | 1.52 (0.31, 2.63) | 1.30 (0.27, 1.82) |

| Male | 52 (47) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Years of practiceb | |||

| ≤ 5 | 43 (39) | 2.68 (1.19, 6.01)* | 2.42 (0.86, 6.87) |

| > 5 | 67 (61) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Type of practice | |||

| Public | 87 (79) | 3.74 (1.39, 10.04)* | 5.13(1.53, 17.24)** |

| Private | 23 (21) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Knows national law mandates confidentiality | |||

| No | 84 (76) | 4.48 (1.68, 11.9)** | 2.28 (0.65, 8.01) |

| Yes | 25 (23) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Knows international law mandates confidentiality | |||

| No | 68 (62) | 5.35 (2.31, 12.36)** | 3.34 (1.15, 9.71)* |

| Yes | 42 (38) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Believes national law mandates reporting of unlawful abortion | |||

| No | 22 (20) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 88 (80) | 2.65 (1.01, 6.98)* | 1.97 (0.6, 6.36) |

| Believes women delay seeking care for fear of prosecution | |||

| No | 15 (14) | 1.10 (0.37, 3.29) | 1.01 (0.25, 4.03) |

| Yes | 95 (86) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Believes confidentiality laws could protect providers who do not report | |||

| No | 35(32) | 2.71 (1.14, 6.4)* | 0.99 (0.33, 2.96) |

| Yes | 75 (68) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Believes it is ethical to not report | |||

| No | 34 (31) | 4.77(1.85, 12.28) ** | 2.56 (0.84, 7.82) |

| Yes | 76 (69) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

aFrom logistic regression, adjusted for all covariates in the table.

bObstetrician-gynecologists with more than 5 years of work experience were in practice before the 1998 legal reforms.

* P < .05; **P < .01.

We identified the following personal rationales for reporting suspected abortions: fear of being accused as an accomplice, religious or moral beliefs, perceived legal obligation, and perceived ethical obligation. Responses mirrored what they perceived to be other health workers’ predominant motives for reporting: perceived legal obligation (42%), followed by fear of being accused as an accomplice (24%), desire to prosecute the unsafe abortion provider (23%), and desire to prosecute the woman who consented to the abortion (11%) (Table 2 ▶). Most (86%) obstetrician-gynecologists surveyed said they believed that women were delaying or avoiding seeking care for fear of being reported, and one half (50%) indicated that they had personally treated a patient who delayed seeking care for this reason.

TABLE 2—

Perceived Motives of Health Care Workers Who Notify Law Enforcement Authorities of Suspected Abortions According to Salvadoran Obstetrician-Gynecologists

| Motive | No (%) |

| Perceived legal obligation | 46 (42) |

| Fear of being mistaken for an accomplice | 27 (24) |

| Unsafe abortion provider should be prosecuted | 25 (23) |

| Woman should go to jail | 12 (11) |

| Total | 110 (100) |

DISCUSSION

Our review of the Salvadoran legal framework revealed a confusing and unenviable situation for public health workers. One code requires providers to report criminal acts, but another bars them from divulging confidential information. Both carry penalties for noncompliance. Ideally, both health care providers and legal authorities would know the full range of laws governing medical practice. However, because the providers’ role is not to interpret and apply criminal law, they may rely on state actors to guide them. Furthermore, given the complex legal framework and competing obligations both to report criminal activities and to preserve confidentiality, the onus should be on judicial and legal authorities to correctly interpret and apply laws protecting privacy and confidentiality and reject as inadmissible all evidence obtained illegally (e.g., through breach of confidentiality).

Although the law may protect health care professionals who choose to honor patients’ privacy in cases of suspected abortion, the public prosecutors appeared to condone the behavior of providers who notified the government of suspected unlawful abortions. State prosecutors have actively initiated criminal investigations of suspected abortions when notified by health care workers, and judges have not questioned this practice. Given this context, it is not surprising that even providers who correctly believed that the law and ethical principles supported the preservation of confidentiality participated in reporting suspected abortions and feared reprisal and accusations of complicity if they did not.

Our findings suggest that providers who were aware of international legal protections were less likely to have been involved in reporting unlawful abortion. These providers may have been more knowledgeable about human rights law and principles and thus may have felt protected while exercising their duty to preserve patients’ privacy. The study results also suggest that providers employed by public health institutions may have been more likely to report women for unlawful abortion than providers employed by private institutions.

There are several logical explanations for these findings. First, public health institutions are more likely to treat indigent women and adolescents who often resort to unsafe, low-cost, and readily detectable abortion methods (e.g., insertion of foreign objects). Second, private sector providers have an explicit profit motive to protect their individual patients’ privacy and avoid legal inconveniences. Finally, because public health care workers are subject to governmental oversight and are susceptible to shifting ministerial politics, they may be more fearful of reprisal if they do not comply with prevailing governmental ideology or policies.

Given the complex legal issues surrounding reporting suspected abortion, providers’ decisions about whether to protect the privacy of patients suspected of unlawful abortion should be guided instead by human rights and ethical considerations. Human rights and ethical duties are derived from the same core values, and both are powerful tools that guide individual behavior and the formulation of laws. Yet both may be limited to protect an overriding public interest, such as public health, when stringent conditions are met.22

Medical ethical guidelines define narrow conditions that allow the disclosure of confidential information.23 According to the Medical Ethics Manual of the World Medical Association, disclosure of confidentiality may be ethically justifiable when all the following conditions are met: (1) nondisclosure implies an immediate and imminent threat to the health or well-being of a person or group of persons, (2) disclosure would reduce the threat, (3) the least information necessary to reduce the threat is disclosed, and (4) disclosure will result in more good than harm.24

To apply these conditions to the case of suspected unlawful abortion, we must distinguish between self-induced abortions and those practiced by an unsafe abortion provider. When providers report women who have a self-induced abortion, they fulfill none of the conditions for the ethical disclosure of confidential information. On the contrary, the ethical principles of nonmaleficence (breaching confidentiality may result in harm to the patient) and beneficence (confidentiality enables prompt diagnosis and treatment) strongly reinforce the preservation of confidentiality.1(p380) However, when the revelation of confidential information leads to the deterrence of unsafe abortion practitioners who may cause harm to additional women, a legitimate interest in the protection of public health may be alleged to justify disclosure.

To assess whether the ends justify the means, the potential health benefits of this practice must be weighed against potential risks and human rights burdens.22 Although disclosure might provide health benefits, we cannot be fully confident that police would be successful in their endeavor to capture the unsafe abortion provider. On the other hand, disclosure would expose individual patients to harm and deter care seeking. Furthermore, this practice would infringe on women’s rights to autonomy and privacy and might lead to discrimination. Only women who unwittingly disclosed that their abortion was not self-induced would place themselves at risk of being reported. Last, there are alternative public health strategies (e.g., contraceptive counseling and methods) for the prevention of unsafe abortions that do not undermine women’s right to privacy or public trust in medical practice.

Thus, on balance, disclosing the identity of patients suspected of having sought an unlawful abortion from an unsafe abortion practitioner does more harm than good and does not satisfy ethical and human rights conditions for the disclosure of confidential information.

Study Limitations

This study has several important limitations. There were no available records of abortion prosecutions preceding the 1998 legal reforms. Thus, we cannot compare the increase in abortion prosecutions against trends before the law change. We were unable to review all legal case records of women whose cases were brought to court during the study period (2000–2003). Consequently, we could not estimate the true proportion of criminal cases in which post-abortion care providers were the original source of the accusation, and our characterization of the sociodemographic characteristics of accused women may not be representative.

In the provider survey, 95% confidence intervals were large and survey results should be interpreted with caution. Our sample of obstetrician-gynecologist members of Association of Obstetrics and Gynecology may not be representative of unaffiliated obstetrician-gynecologists or of all public health providers in El Salvador.

Conclusions

There is often a compelling public health rationale for laws that mandate the reporting of otherwise privileged patient information. These laws usually do not contravene medical ethical principles, but when they require providers to report unlawful abortion, they do.3 The results of this study suggest that Salvadoran health care providers commonly breach patient confidentiality to implicate women for unlawful abortion and do so despite widespread recognition that this practice dissuades women from seeking emergency care. This practice violates legal, human rights, and medical professional ethical principles.

National and international public health and human rights activists must raise policymakers’ awareness of the legal framework that protects the privacy of women in need of postabortion care. Human rights treaty-monitoring bodies, responsible for ensuring state compliance with international law, have recognized that women’s rights to privacy and nondiscrimination are violated when states require providers to report unlawful abortion.25,26 Thus, activists may petition treaty bodies to challenge the Salvadoran government to clarify its position on this issue as well as confront state authorities directly.

Women accused of unlawful abortion should be assisted in bringing suit against health care providers who violated their legal right to privacy. Laws protecting confidentiality should be enforced and violators punished. Researchers must play an important role in documenting the health consequences and social impact of ethical violations for women and providers.

Health care providers must be educated about the human rights and ethical principles that underpin confidentiality, national and international law, and mechanisms for resolving potential ethical conflicts. It should be emphasized that providers who disclose confidential information are responsible for justifying their decision under the law and according to ethical principles. Furthermore, medical professional societies need to work with lawyers and public health authorities to develop clear guidelines that describe health care workers’ responsibility to preserve confidentiality and protect patients’ privacy and outline a process for resolving cases in which legal and ethical mandates may conflict. These guidelines should refer specifically to the narrow ethical and legal circumstances in which confidentiality may be limited and analyze how ethical principles apply to common patient care situations in which confidential information should (e.g., preventing future child abuse) and should not (e.g., punishing unlawful abortion) be disclosed. Finally, the Ministry of Health should publish its policies in the community and encourage timely care seeking for women to prevent morbidity and mortality and to restore public trust.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Inter-church Organization for Cooperative Development of the Netherlands (grant N11006011) and the Department of International Development of the United Kingdom (grant AG2835).

We thank C. E. Mujer, Dr. Patricia Hernandez, and Dr. Patricia Ramirez for their contributions to the study. We also thank the Salvadoran Association of Obstetrics and Gynecology for agreeing to collaborate with the study. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions of Rebecca Cook, Janie Benson, Charlotte Hord Smith, and Maria Gallo.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors H.L. McNaughton, M.M. Blandon, and K. Padilla originated the study. All authors contributed to the study design, data analysis, and interpretation. H.L. McNaughton and E.M.H. Mitchell wrote the article. All translations from Spanish to English were by H.L. McNaughton.

References

- 1.Cook RJ, Dickens BM, Fathalla MF. Reproductive Health and Human Rights: Integrating Medicine, Ethics, and Law. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- 2.Center for Reproductive Law and Policy. Persecuted: Political Process and Abortion Legislation in El Salvador—A Human Rights Analysis. New York, NY: Center for Reproductive Rights; 2000. Available at: http://www.reproductiverights.org/pdf/persecuted1.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2006.

- 3.Dickens BM, Cook RJ. Law and ethics in conflict over confidentiality? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000;70: 385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvadoran Demographic Association. National Family Health Survey 1993. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1993.

- 5.Salvadoran Demographic Association. National Family Health Survey 1998. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998.

- 6.Salvadoran Demographic Association. National Family Health Survey 2003. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003.

- 7.Colegio Medico de El Salvador. Código de Ética Medica Del Colegio Medico de El Salvador. San Salvador, El Salvador: El Colegio Medico de El Salvador; February, 1986. Art 56: “El secreto profesional es un deber que nace de la esencia misma de la profesión. El interés publico, la seguridad del los enfermos, la honra de las familias, la respetabilidad del profesional y la dignidad del arte exigen el secreto. El medico tiene el deber de conservar como secreto todo lo que vea, oiga o descubra en el ejercicio de su profesión.” [The professional secret is a fundamental duty of the [health care] profession. The public interest, the security of sick persons, family honor, respect for the [health care] professional and the dignity of health care practice compel the preservation of the [professional] secret. The physician must preserve as secret all that he/she sees, hears or discovers in the context of his/ her professional role.]

- 8.Bok S. The limits of confidentiality. Hastings Cent Rep. 1983;13(1):24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Considerations for Formulating Reproductive Health Laws. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. WH0/RHR/00/1.

- 10.Republica de El Salvador. Código de Salud (con reformas incorporadas). Editorial Jurídica Salvadoreña; 2001. Art 38: “El secreto profesional se recibe bajo dos formas: a) el secreto explícito formal, textualmente confiado por el paciente al profesional; b) el secreto implícito que resulta de las relaciones del paciente con el profesional. El secreto profesional es inviolable; salvo el caso de que, mantenerlo, vulnere las leyes vigentes, o se tenga que revelar en un peritaje o para notificar enfermedades infecto contagiosas ante las autoridades de salud.” [A professional secret may be established in 2 ways: a) the formal explicit secret, literally entrusted by the patient to the health care professional; b) an implicit secret that results from the relationship between the patient and the health care professional. The professional secret cannot be violated unless, by maintaining the secret, a law would be violated, or where the secret must be revealed as part of a forensic evaluation or to notify public health authorities of infectious disease.] Art 284: “Constituyen infracciones graves contra la salud:... 2) la revelación del secreto profesional establecido en los Arts. 37 y 38 del presente Código” [Severe infractions of the health code include . . . 2) the revelation of the professional secret established in articles 37 and 38 of this Code] Art 282: “Serán sancionados con suspensión en el ejercicio profesional, los profesionales de salud que cometan las infracciones establecidas en el Art. 284 de este Código. . . . ” [Health care professionals who commit infractions of the type specified in article 284 of this Code will be punished by having their professional licenses suspended. . . .]

- 11.Republica de El Salvador. Códigos Penal y Procesal: ley penitenciaria y su reglamento. Editorial Jurídica Salvadoreña; 2001. Código Penal, Art 187: “El que revelare un secreto del que se ha impuesto en razón de su profesión u oficio, será sancionado con prisión de seis meses a dos años e inhabilitación especial de profesión u oficio de uno a dos años.” [Individuals who reveal professional secrets will receive a punishment of between 6 months and 2 years of prison and will have their professional licenses revoked for between 1 and 2 years.]

- 12.Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, 18 Dec. 1979. GA Res 34/ 180, UN GAOR, 34th Sess, supp No. 46 at 193, UN Doc A/34/46, entered into force Sept. 3, 1981. Available at: http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/e1cedaw.htm. Accessed May 18, 2005. [Ratified by El Salvador September 18, 1981; Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/english/countries/ratification/8.htm. Accessed May 18, 2005].

- 13.International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 Dec. 1966. 999 UNTS 171, entered into force 23 Mar 1976. Available at: http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/b3ccpr.htm. Accessed May 18, 2005. [Ratified by El Salvador November 3, 1979. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/english/countries/ratification/4.htm. Accessed May 18, 2005.]

- 14.Human Rights Committee, General Comment 28: Equality of Rights between Men and Women (Article 3). UN GAOR 2000, UN Doc A/55/40, annex VI. Available at http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/RHR_01_5_advancing_safe_motherhood/RHR_01_5_appendix8.en.html. Accessed January 21, 2006.

- 15.Republica de El Salvador. Constitución con sus reformas. Editorial jurídica Salvadoreña; 2002. Art 144: “Los tratados internacionales celebrados por El Salvador con otros Estados o con organismos internacionales, constituyen leyes de la República al entrar en vigencia, conforme a las disposiciones del mismo tratado y de esta Constitución. La ley no podrá modificar o derogar lo acordado en un tratado vigente para El Salvador. En caso de conflicto entre el tratado y la ley, prevalecerá el tratado.” [International treaties with other States or international bodies that are acknowledged by El Salvador constitute national laws once they are ratified, in accordance with the dispositions of the treaty and of this Constitution. National law cannot change or disavow the provisions of a valid treaty. In the case of conflict between the provisions of a treaty and the law, the treaty provisions will prevail.]

- 16.Republica de El Salvador. Códigos Penal y Procesal: ley penitenciaria y su reglamento. Editorial Jurídica Salvadoreña; 2001. Código Penal, Art 312: “El funcionario o empleado público, agente de autoridad pública que en el ejercicio de sus funciones o con ocasión de ellas, tuviere conocimiento de haberse perpetrado un hecho punible y omitiendo dar aviso dentro del plazo de 24 horas al funcionario competente, será sancionado con 50 a 100 días multa. Igual sanción se impondrá al jefe o persona encargada de un centro hospitalario, clínica u otro establecimiento semejante, público o privado, que no informare al funcionario competente del ingreso de una persona lesionada dentro de las 8 horas siguientes al mismo, en casos que racionalmente deberán considerarse como provenientes de un delito.” [A funtionary or public employee, agent of public authority who becomes aware of an unlawful act during the exercise of his or her responsibilities and does not report it within 24 hours will be levied a fine of between 50 and 100 days’ pay. The same punishment will be applied to the supervisor or manager of a hospital, health center or other public or private establishment that does not report admitting a patient who was injured in what could reasonably be considered a criminal act within 8 hours of seeking care.]

- 17.Republica de El Salvador. Códigos Penal y Procesal: ley penitenciaria y su reglamento. Editorial Jurídica Salvadoreña; 2001. Código Penal, Art 232: “Tendrán la obligación de denunciar los delitos de acción pública: 2) Los médicos, farmacéuticos, enfermeros o demás personas que ejerzan profesiones relacionadas con la salud, que conozcan esos hechos al prestar los auxilios de su profesión, SALVO que el conocimiento adquirido por ellos este bajo el amparo del secreto profesional” (italics added). [Doctors, pharmacists, nurses and other health professionals must report unlawful criminal acts that they become aware of in the context of their professional relationship, unless the information they acquire is protected under the terms of professional secrecy.]

- 18.Republica de El Salvador. Códigos Penal y Procesal: ley penitenciaria y su reglamento. Editorial Jurídica Salvadoreña; 2001. Código Penal, Art 187: “No podrán declarar los hechos que han llegado a su conocimiento en razón del propio estado, oficio o profesión, bajo pena de nulidad, los ministros de una iglesia con personalidad jurídica, los abogados, notarios, médicos, farmacéuticos y obstetras, según los términos del secreto profesional y los funcionarios públicos sobre secretos de Estado” (italics added). [Under the terms of professional secrecy, official ministers of the Church, lawyers, notaries, physicians, pharmacists and obstetricians cannot declare acts that are protected under the terms of professional secrecy, under penalty of nullification, nor can public employees report State secrets.]

- 19.According to the Women’s Health division of the Salvadoran Ministry of Health and Public Assistance, uterine evacuations are only performed by obstetrician-gynecologists. However, there are currently no policy guidelines regulating the type of provider authorized to perform uterine evacuation. Gerencia de la Mujer del Ministerio de Salud y Asistencia Publica. Personal telephone communication. August 28, 2005.

- 20.Office of the Public Prosecutor for the Republic of El Salvador (Fiscalia General de la Republica de El Salvador), Statistics Unit, Abortion Cases: 2000–2003.

- 21.Proceso penal numero 67–1–2004. Tribunal Primero de Sentencia, Ciudad de San Salvador, 29 de Marzo de 2004. El Salvador.

- 22.International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and Francois-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights. The public health-human rights dialogue. In: Mann JM, Gruskin S, Grodin MA, Annas GJ, eds. Health and Human Rights: A Reader. New York, NY: Routledge Press; 1999: 46–54.

- 23.Lachmann PJ. Consent and confidentiality—where are the limits? An introduction. J Med Ethics. 2003;29:2–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams JA. World Medical Association: Medical Ethics Manual. Ferney-Voltaire Cedex, France: World Medical Association; 2005. Available at: http://www.wma.net/e/ethicsunit/pdf/manual/ethics_manual.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2006.

- 25.International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 Dec. 1966. 999 UNTS 171, entered into force 23 Mar 1976. Available at: http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/b3ccpr.htm. Accessed May 18, 2005. [Ratified by El Salvador November 3, 1979. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/english/countries/ratification/4.htm. Accessed May 18, 2005.] No. 20: “States may fail to protect women’s privacy . . . where [they] impose a legal duty upon doctors and other health personnel to report cases of women who have undergone abortion. In these instances, other rights in the Covenant, such as those of articles 6 [right to life] and 7 [right to be free from inhuman and degrading treatment], might also be at stake.”

- 26.Human Rights Committee, General Comment 28: Equality of Rights between Men and Women (Article 3). UN GAOR 2000, UN Doc A/55/40, annex VI. Available at http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/RHR_01_5_advancing_safe_motherhood/RHR_01_5_appendix8.en.html. Accessed January 21, 2006. Paragraph 12(d): “Whereas lack of respect for the confidentiality of patients will affect both men and women, it may deter women from seeking advice and treatment and thereby adversely affect their health and well-being. Women will be less willing, for that reason, to seek medical care for . . . incomplete abortion. . . .”