Abstract

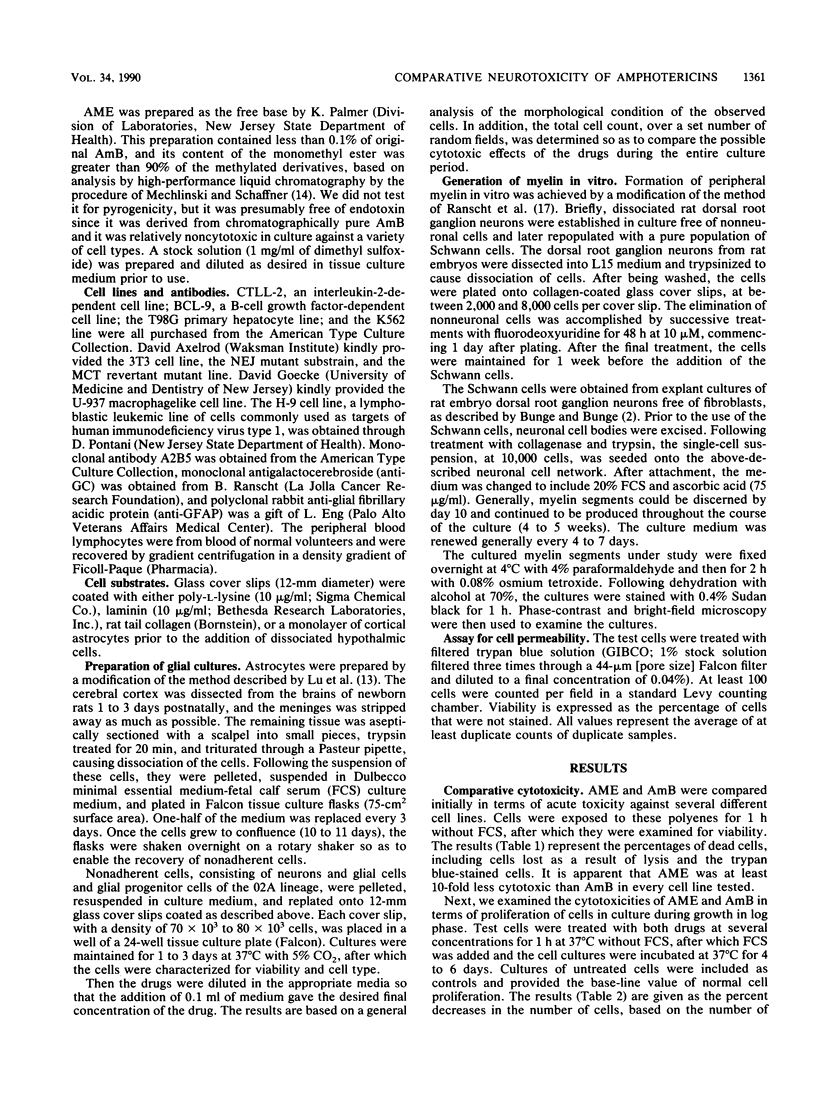

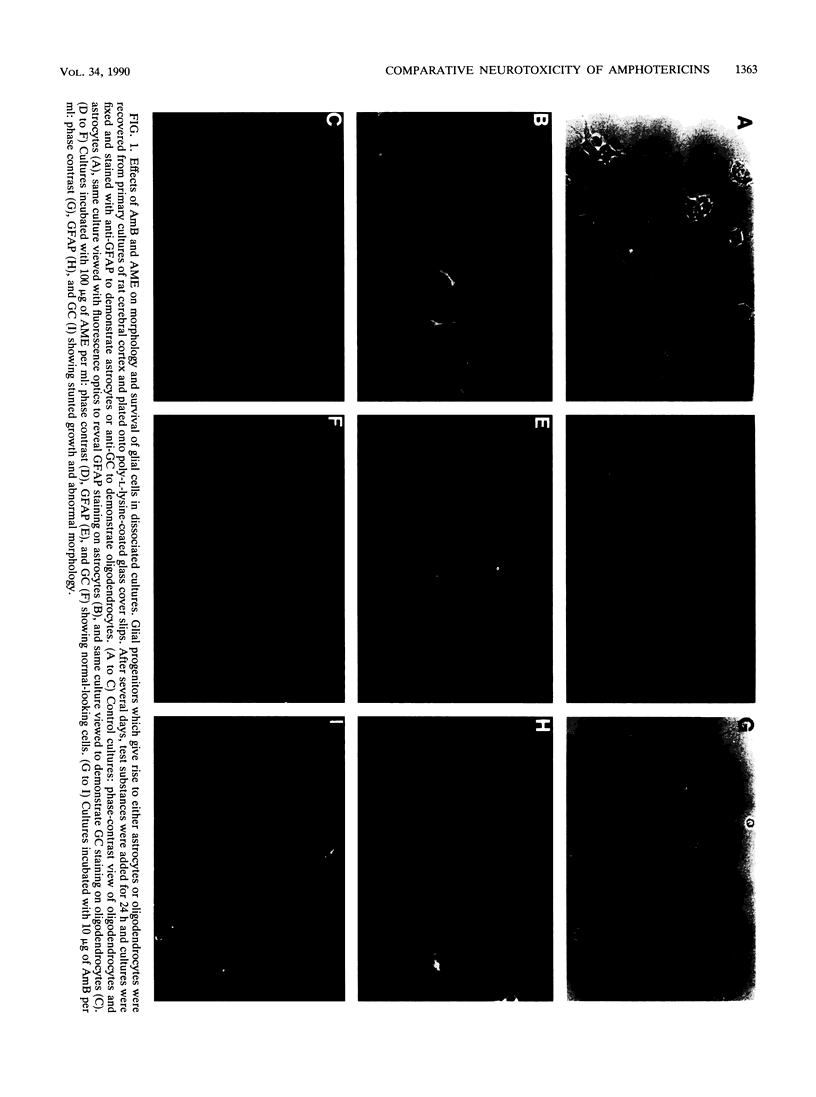

Amphotericin B (AmB) is a potent antifungal polyene macrolide antibiotic and is the drug of choice for the treatment of deep-seated mycotic infections. Its use is limited, owing to its nephrotoxicity, and it must be dispersed in deoxycholate for parenteral administration. In contrast, AME (the monomethyl derivative of AmB) is water dispersible, is appreciably less cytotoxic than AmB toward a variety of cell types, and is reportedly active against the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome virus (human immunodeficiency virus type 1). The latter activity has generated interest in AME as an antiviral drug. However, AME is perceived to be neurotoxic, based on the outcome of a human clinical trial of AME as an antifungal drug. AmB is not regarded as neurotoxic, presumably because any neurotoxicity in vivo is precluded by its nephrotoxicity. It was important, therefore, to determine the potential for neurotoxicity of the two agents in comparative tests, assessing the effects of their direct action against neural cells in culture. Rat cortical cells, comprising astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, were used. AME was at least 10 times less toxic than AmB and equally less toxic against several other nonneural cell types also included in these tests. Equally important, AmB disrupted the myelin sheath in these cultures, and it inhibited its generation. AME did not, even at a concentration 10 times greater than the toxic concentration of AmB. AmB is, therefore, potentially more neurotoxic than AME, contrary to current perception. AME is effective as an antifungal and antiviral drug at a concentration far below its toxic concentration for neural cells. Also, AME does not cross the blood-brain barrier appreciably, so that a therapeutic level in blood can be expected without encountering neurotoxicity.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bonner D. P., Mechlinski W., Schaffner C. P. Polyene macrolide derivatives. 3. Biological properties of polyene macrolide ester salts. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1972 Apr;25(4):261–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge M. B., Bunge R. P. Linkage between Schwann cell extracellular matrix production and ensheathment function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;486:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb48077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale N. T., Galgiani J. N., Stevens D. A., Herrick M. K., Langston J. W. Amphotericin B-induced myelopathy. Arch Intern Med. 1980 Sep;140(9):1189–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O., Lemann W., Evans A. C., Moeller J. R., Rottenberg D. A. Akinetic mutism in a bone marrow transplant recipient following total-body irradiation and amphotericin B chemoprophylaxis. A positron emission tomographic and neuropathologic study. Arch Neurol. 1987 Apr;44(4):414–417. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1987.00520160048013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis W. G., Bencken E., LeCouteur R. A., Barbano J. R., Wolfe B. M., Jennings M. B. Neurotoxicity of amphotericin B methyl ester in dogs. Toxicol Pathol. 1988;16(1):1–9. doi: 10.1177/019262338801600101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis W. G., Sobel R. A., Nielsen S. L. Leukoencephalopathy in patients treated with amphotericin B methyl ester. J Infect Dis. 1982 Aug;146(2):125–137. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerkens J. F., Branch R. A. The influence of sodium status and furosemide on canine acute amphotericin B nephrotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1980 Aug;214(2):306–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybill J. R., Ellenbogen C. Complications with the Ommaya reservoir in patients with granulomatous meningitis. J Neurosurg. 1973 Apr;38(4):477–480. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.38.4.0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeprich P. Amphotericin B methyl ester and leukoencephalopathy: the other side of the coin. J Infect Dis. 1982 Aug;146(2):173–176. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim G. R., Sibley P. L., Yoon Y. H., Kulesza J. S., Zaidi I. H., Miller M. M., Poutsiaka J. W. Comparative toxicological studies of amphotericin B methyl ester and amphotericin B in mice, rats, and dogs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976 Oct;10(4):687–690. doi: 10.1128/aac.10.4.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu E. J., Brown W. J., Cole R., deVellis J. Ultrastructural differentiation and synaptogenesis in aggregating rotation cultures of rat cerebral cells. J Neurosci Res. 1980;5(5):447–463. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490050510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechlinski W., Schaffner C. P. Separation of polyene antifungal antibiotics by high-speed liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1974 Nov 6;99(0):619–633. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)90890-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monji N., Bonner D. P., Hashimoto Y., Schaffner C. P. Studies on the absorption, distribution and excretion of radioactivity after intravenous and intraperitoneal administration of 14C-methyl ester of amphotericin B. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975 Apr;28(4):317–324. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSEN E., BELBER J. P. Coccidioidal meningitis of long duration; report of a case of four years and eight months duration, with necropsy findings. Ann Intern Med. 1951 Mar;34(3):796–809. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-34-3-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranscht B., Wood P. M., Bunge R. P. Inhibition of in vitro peripheral myelin formation by monoclonal anti-galactocerebroside. J Neurosci. 1987 Sep;7(9):2936–2947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-09-02936.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEABURY J. H. Experience with amphotericin B. Chemotherapia (Basel) 1961;3:81–94. doi: 10.1159/000219534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner C. P., Plescia O. J., Pontani D., Sun D., Thornton A., Pandey R. C., Sarin P. S. Anti-viral activity of amphotericin B methyl ester: inhibition of HTLV-III replication in cell culture. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986 Nov 15;35(22):4110–4113. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterharnscheidt F., De Beukelaer M., Simon J. L. Chronic untreated coccidioidomycosis of the central nervous system: a case of 7 and-one-half years duration. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1969 Summer;27(2):513–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINN W. A. The use of amphotericin B in the treatment of coccidioidal disease. Am J Med. 1959 Oct;27:617–635. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(59)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn R. E., Bower J. H., Richards J. F. Acute toxic delirium. Neurotoxicity of intrathecal administration of amphotericin B. Arch Intern Med. 1979 Jun;139(6):706–707. doi: 10.1001/archinte.139.6.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]