Abstract

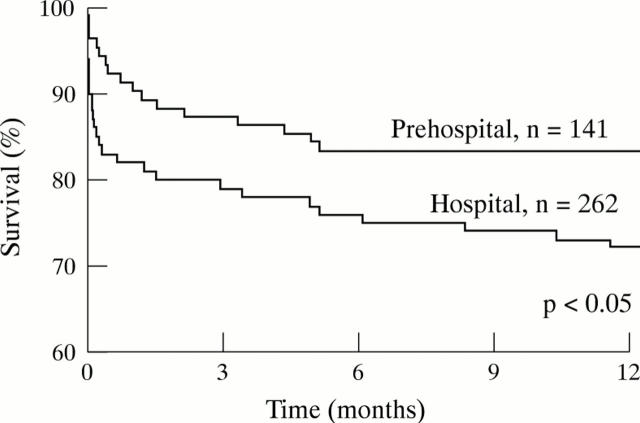

Background—In the Grampian region early anistreplase trial (GREAT), domiciliary thrombolysis by general practitioners was associated with a halving of one year mortality compared with hospital administration. However, after completion of the trial and publication of the results, the use of this treatment by general practitioners declined sharply. Objective—To increase the proportion of eligible patients receiving timely thrombolytic treatment from their general practitioners. Setting—Practices in Grampian located ⩾ 30 minutes' travelling time from Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, where patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction were referred after being seen by general practitioners. Audit standard—A call-to-needle time of 90 minutes, as proposed by the British Heart Foundation (BHF). Methods—Findings of this audit of prehospital management of acute myocardial infarction were periodically fed back to the participating doctors, when practice case reviews were also conducted. Results—Of 414 administrations of thrombolytic treatment, 146 (35%) were given by general practitioners and 268 (65%) were deferred until after hospital admission. Median call-to-needle times were 45 (94% ⩽ 90) and 145 (7% ⩽ 90) minutes, respectively. Survival at one year was improved with prehospital compared with hospital thrombolysis (83% v 73%; p < 0.05). The proportion of patients receiving thrombolytic treatment from their general practitioners did not increase during the audit. Conclusions—In practices ⩾ 30 minutes from hospital, the BHF audit standard was readily achieved if general practitioners gave thrombolytic treatment, but not otherwise. Knowledge of the benefits of early thrombolysis, and feedback of audit results, did not lead to increased prehospital thrombolytic use. Additional incentives are required if general practitioners are to give thrombolytic treatment. Keywords: thrombolysis; general practitioners; prehospital care; acute myocardial infarction

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (92.2 KB).

Figure 1 .

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients given thrombolytic treatment prehospital or in hospital.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- McCrea W. A., Saltissi S. Electrocardiogram interpretation in general practice: relevance to prehospital thrombolysis. Br Heart J. 1993 Sep;70(3):219–225. doi: 10.1136/hrt.70.3.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawles J. Attitudes of general practitioners to prehospital thrombolysis. BMJ. 1994 Aug 6;309(6951):379–382. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6951.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawles J. Guidelines for general practitioners administering thrombolytics. Drugs. 1995 Oct;50(4):615–625. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199550040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rule S., Brooksby P., Sanderson J. Use of thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction by general practitioners. Postgrad Med J. 1993 Mar;69(809):190–193. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.69.809.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale L., Silcock J., Rawles J. An economic evaluation of thrombolysis in a remote rural community. BMJ. 1997 Feb 22;314(7080):570–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston C. F., Penny W. J., Julian D. G. Guidelines for the early management of patients with myocardial infarction. British Heart Foundation Working Group. BMJ. 1994 Mar 19;308(6931):767–771. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]