Abstract

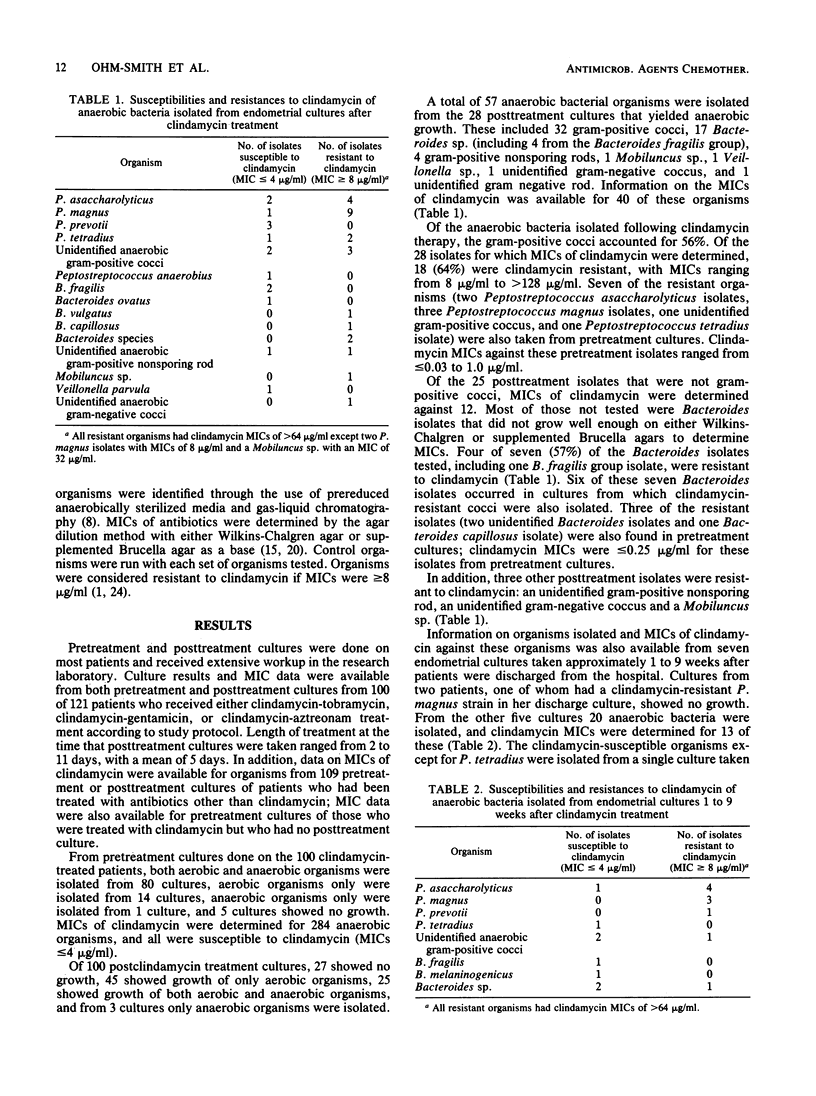

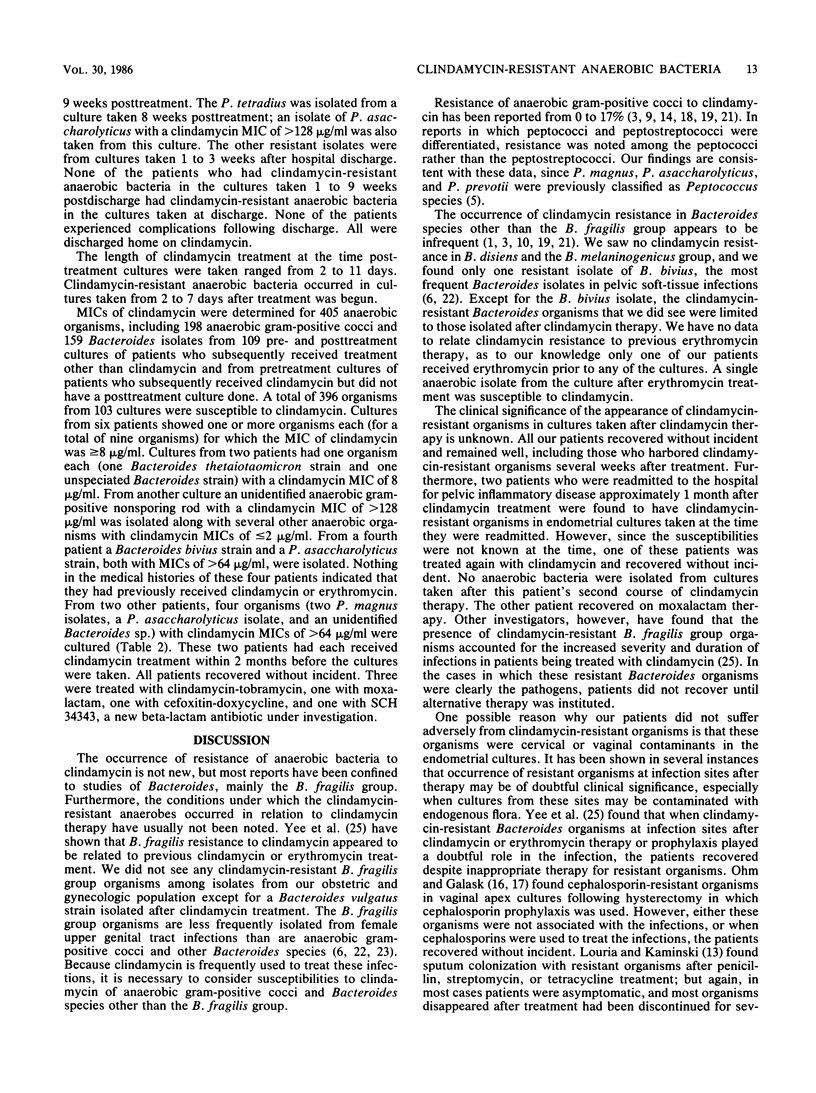

MICs of clindamycin were determined by the agar dilution method against anaerobic organisms isolated from endometrial cultures in women with pelvic soft tissue infections. Cultures were obtained from 100 women both before and after clindamycin therapy, from 107 women before therapy with clindamycin or another antimicrobial agent or after treatment with an antimicrobial agent other than clindamycin, and from 9 women 1 to 9 weeks after they were discharged from the hospital following clindamycin therapy. Only 5 (0.7%) of 685 isolates tested from women who had not received clindamycin therapy were resistant to clindamycin. From the 100 cultures taken immediately after clindamycin therapy, 57 anaerobic bacteria were isolated from 28 cultures. Of the 40 anaerobic organisms for which MICs of clindamycin were determined, 25 (62.5%) were resistant to clindamycin (MIC greater than or equal to 8 micrograms/ml). The most common organisms isolated after therapy were the anaerobic gram-positive cocci (of which 32 isolates were discovered); of 28 coccal isolates tested, 64% were clindamycin resistant. Four of seven (57%) of the Bacteroides isolates tested, one unidentified gram-positive nonsporing rod, one unidentified gram-negative coccus, and one Mobiluncus sp. were also clindamycin resistant. Of 18 anaerobic isolates from the nine cultures taken 1 to 9 weeks after hospital discharge, 55% were resistant to clindamycin. The clinical significance of these findings is unknown since all patients recovered without incident and remained well. However, the data suggest that physicians need to be aware that patients with recent exposure to clindamycin may have clindamycin-resistant anaerobic organisms in a current infection. This may prevent the infection from responding to clindamycin treatment.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Acar J. F., Goldstein F. W., Kitzis M. D., Eyquem M. T. Resistance pattern of anaerobic bacteria isolated in a general hospital during a two-year period. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981 Dec;8 (Suppl 500):9–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/8.suppl_d.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco J. D., Gibbs R. S., Duff P., Castaneda Y. S., St Clair P. J. Randomized comparison of ceftazidime versus clindamycin-tobramycin in the treatment of obstetrical and gynecological infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983 Oct;24(4):500–504. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.4.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W. J., Waatti P. E. Susceptibility testing of clinically isolated anaerobic bacteria by an agar dilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980 Apr;17(4):629–635. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.4.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan V. K., Thadepalli H. Clindamycin: a review of fifteen years of experience. Rev Infect Dis. 1982 Nov-Dec;4(6):1133–1153. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.6.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall S. A., Kohan A. P., Ayers O. M., Hughes C. E., Addison W. A., Hill G. B. Intravenous metronidazole or clindamycin with tobramycin for therapy of pelvic infections. Obstet Gynecol. 1981 Jan;57(1):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs R. S., Blanco J. D., Castaneda Y. S., St Clair P. J. A double-blind, randomized comparison of clindamycin-gentamicin versus cefamandole for treatment of post-cesarean section endomyometritis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982 Oct 1;144(3):261–267. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90576-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye D., Kobasa W., Kaye K. Susceptibilities of anaerobic bacteria to cefoperazone and other antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980 Jun;17(6):957–960. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby B. D., George W. L., Sutter V. L., Citron D. M., Finegold S. M. Gram-negative anaerobic bacilli: their role in infection and patterns of susceptibility to antimicrobial agents. I. Little-known Bacteroides species. Rev Infect Dis. 1980 Nov-Dec;2(6):914–951. doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.6.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuppel R. A., Scerbo J. C., Dzink J., Mitchell G. W., Jr, Cetrulo C. L., Bartlett J. Quantitative transcervical uterine cultures with a new device. Obstet Gynecol. 1981 Feb;57(2):243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOURIA D. B., KAMINSKI T. The effects of four antimicrobial drug regimens on sputum superinfection in hospitalized patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1962 May;85:649–665. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1962.85.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeFrock J. L., Molavi A., Prince R. A. Clindamycin. Med Clin North Am. 1982 Jan;66(1):103–120. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W. J., Gardner M., Washington J. A., 2nd In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria isolated from clinical specimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972 Feb;1(2):148–158. doi: 10.1128/aac.1.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm M. J., Galask R. P. The effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. I. Effect on morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976 Jun 15;125(4):442–447. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm M. J., Galask R. P. The effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on patients undergoing vaginal operations. II. Alterations of microbial flora. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975 Nov 15;123(6):597–604. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90881-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe R. D., Finegold S. M. Comparative in vitro activity of new beta-lactam antibiotics against anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981 Nov;20(5):600–609. doi: 10.1128/aac.20.5.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell T. C., Marshall J. R., Chow A. W. Antimicrobial therapy of postpartum endomyometritis. I. Comparative susceptibility of mezlocillin and other antibiotics to genital anaerobic bacteria. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981 Oct 1;141(3):242–245. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter V. L., Finegold S. M. Susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria to 23 antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976 Oct;10(4):736–752. doi: 10.1128/aac.10.4.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet R. L., Ohm-Smith M., Landers D. V., Robbie M. O. Moxalactam versus clindamycin plus tobramycin in the treatment of obstetric and gynecologic infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985 Aug 1;152(7 Pt 1):808–817. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(85)80068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson R. M., Michaelson T. C., Daly M. J., Spalding E. H. Clindamycin in infections of the female genital tract. Obstet Gynecol. 1974 Nov;44(5):699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tally F. P., Sosa A., Jacobus N. V., Malamy M. H. Clindamycin resistance in Bacteroides fragilis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981 Dec;8 (Suppl 500):43–48. doi: 10.1093/jac/8.suppl_d.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee M. H., Guiney D. G., Hasegawa P., Davis C. E. The clinical significance of clindamycin-resistant Bacteroides fragilis. JAMA. 1982 Oct 15;248(15):1860–1861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]