Abstract

Objective: To make a prospective assessment of the clinical and prognostic correlates of angiographically diffuse non-obstructive coronary lesions.

Design: Angiographic vessel and extent scores were calculated in 228 clinically stable patients (mean (SD) age, 60 (11) years; 43 women, 185 men) undergoing prospective follow up for the composite end point of death and myocardial infarction. The effect on outcome of clinical variables (age, sex, previous myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, smoking habit, systemic hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, ejection fraction) and angiographic variables (vessel and extent score) was evaluated by Cox’s proportion hazard model.

Results: The vessel score was 3 in 34 patients (15%), 2 in 78 (34%), 1 in 87 (38%), and 0 in 29 (13%). Median extent score was 60 (range 6–110; first quartile 40, third quartile 70). Forty one events (nine deaths and 32 myocardial infarcts) occurred over a median follow up period of 30 months. Age and extent score were the only multivariate predictors of outcome, but the latter provided 28% additional prognostic information after adjustment for the most predictive variables (gain in χ2 = 7, p < 0.01). A vessel score of 3 was associated with worse survival, while no significant discrimination was possible among the other groups. However, assignment of patients to two groups according to an ROC curve derived cut off value for the extent score made it possible to obtain significant discrimination of survival even in cases with vessel scores of 0 to 2. Age and diabetes were clinical markers of a higher extent score.

Conclusions: The angiographic extent score is a powerful marker of adverse outcome independent of severity and the number of flow limiting coronary lesions, and may reflect the link between clinical risk profile and diffusion of coronary atherosclerosis. Thus it should be of clinical value for targeting aggressive preventive measures.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, angiography, prognosis

The severity of coronary artery disease, the site of stenoses, and the number of diseased vessels are known to influence prognosis, particularly with regard to cardiac mortality.1 The severity of coronary artery stenoses shown by angiograms is most commonly measured as per cent diameter narrowing relative to the normal lumen size adjacent to the stenotic segment. However, coronary atherosclerosis is usually diffuse and the normal reference segment is frequently narrowed as well.2,3 Moreover, serial segmental narrowing, representing a commonly encountered type of diffuse disease, is not accounted for by simple percentage narrowing because of absence of a true normal reference segment, or methods of quantifying the cumulative effects of multiple stenoses. Thus information on seemingly milder, non-obstructive lesions may often be missed and their prognostic importance underestimated. On the other hand, it is known that plaque rupture or erosion with superimposed occlusive thrombosis, underlying acute coronary syndromes or sudden death, often occurs at sites of less than 50% diameter stenoses.4–7

Some years ago the extent score was proposed,8 to quantify the proportion of coronary endothelial surface area affected by atheroma. We have used this score to quantify the proportion of the coronary circulation involved by atheroma and have sought to assess its clinical and prognostic correlates prospectively.

METHODS

Study population

The initial study population consisted of 439 clinically stable patients undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography on the basis of clinical or non-invasive stress test data and with prospective follow up. Of these, 211 were revascularised by means of either bypass surgery or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty within six months of the index angiography and were excluded from the study to avoid possible referral bias. Thus 228 conservatively managed patients (mean (SD) age, 60 (11) years; 43 women, 185 men) went on with their follow up programme and formed the study population.

Coronary angiography

Selective coronary cineangiography was done from the brachial or femoral approach using Judkin’s or Sones’s technique. Multiple views were obtained in all patients, with the left anterior descending and left circumflex coronary arteries visualised in at least four views and the right coronary artery in at least two views. All coronary and left ventricular angiograms were interpreted by two experienced observers, and differences in interpretation were resolved by consensus. Degree of stenosis was defined as the greatest percentage reduction of luminal diameter in any view compared with the nearest normal segment (per cent diameter stenosis) and was determined using the calliper technique.9 The vessel score indicated the number of coronary arteries with ⩾ 70% stenosis (⩾ 50% for the left main coronary artery). The extent score was calculated as previously suggested.8 In brief, any luminal irregularity identifying the segment of vessel involved by atheroma is multiplied by a specific factor for each coronary vessel: 5 for the left main artery; 20 for the left anterior descending artery; 10 for the main diagonal branch; 5 for the first septal perforator; 20 (10 if small) for the left circumflex artery; 10 (20 if large marginal) for obtuse marginal and posterolateral vessels; 20 for the right coronary artery; and 10 for the main posterior descending branch. The numerical sum of the scores obtained for each individual vessel gives the total score, which ranges from 0–100, providing an estimation of the percentage of the coronary surface involved by atheroma. In case of incomplete collateralisation of an occluded vessel, this is assigned the mean extent score of vessels proximal to the occlusion.

The ejection fraction was calculated by means of left ventriculography.

Follow up

Follow up information was obtained by prospectively determined visits at our outpatient clinic, by discharge reports from other hospitals in case of emergency admission, and by telephone interviews with the patient, his close relative, or his referring physician.

Death and myocardial infarction represented the target events of the study. Owing to the difficulty in ascribing a cardiac origin to deaths occurring suddenly, the overall mortality was used as an unbiased and objective end point.10,11 Myocardial infarction was diagnosed on the basis of documented ECG changes and typical cardiac enzyme release.

Patients undergoing revascularisation were censored at the time of the procedure.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean (SD) and were compared by unpaired two sample t tests in case of normal distribution and by the Mann–Whitney test in case of non-normal distribution. Normality was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The 95% confidence interval (CI) is reported when appropriate. Proportions were compared by χ2 statistics. The individual effect of clinical and angiographic variables on survival was evaluated by means of Cox’s proportional hazard model using a stepwise forward procedure. At each step a significance of 0.1 was required to enter into the model. The χ2 value was calculated from the log likelihood ratio. A significant increase in global χ2 of the model after the addition of further variables was considered to indicate incremental prognostic value. Cumulative survival curves as a function of time were generated with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log rank test. The effect of clinical variables on the extent score was assessed by the general linear model univariate procedure, which provides regression analysis and analysis of variance for one dependent variable by one or more independent variables. Statistical significance was settled at a probability value of p < 0.05. The area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve method12 was used to select the cut off value of the extent score providing the best discrimination of risk. The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, release 10.0 for Microsoft Windows) was used.

RESULTS

Angiographic findings

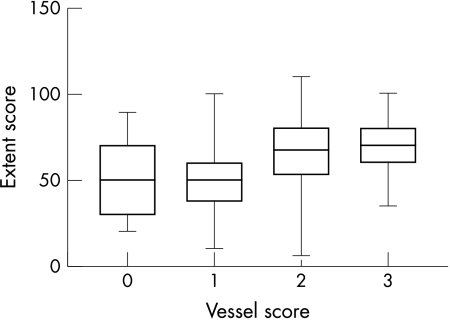

The vessel score was 3 in 34 patients (15%), 2 in 78 (34%), 1 in 87 (38%), and 0 in 29 (13%). The left main stem was affected in five patients (2%), the left anterior descending coronary artery in 125 (55%), the circumflex coronary artery in 101 (44%), and the right coronary artery in 117 (51%). The median extent score was 60 (range 5–110; first quartile 40, third quartile 70). Extent score distribution according to vessel score is shown in fig 1; a variation over a wide range is evident for vessel scores of 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Extent score distribution according to the vessel score. The box extends from the first to the third quartile, with a horizontal line at the median. Whiskers extend down to the smallest value and up to the largest.

Follow up events

Mean follow up time was 30 months (95% confidence interval, 25 to 32 months). No patient was lost to follow up. Forty one target events occurred (nine deaths and 32 non-fatal myocardial infarcts). Seven of the nine deaths were related to proven cardiac factors (fatal myocardial infarction or acute heart failure), while two occurred suddenly. In addition, 18 patients underwent revascularisation procedures (13 bypass surgery and five coronary angioplasty) at six months or more after the index angiography.

Outcome prediction

The characteristics of the study population according to outcome are shown in table 1. Patients with follow up events were older, more often diabetic, and had significantly higher vessel and extent scores compared with patients without events. Age, diabetes, a vessel score of 3, and extent score were univariate predictors of the cumulative end point of death and myocardial infarction, but only age and extent score were also significantly and independently associated with the outcome on multivariate analysis (table 2). After adjustment for the most predictive variables, the extent score provided 28% additional prognostic information (gain in χ2 = 7, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population according to the outcome

| Variable | Events (n=41) | No events (n=187) | p Value |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 66 (8.2) | 58 (11) | 0.0001 |

| Male sex | 30 (73%) | 155 (83%) | 0.20 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 29 (71%) | 153 (82%) | 0.17 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (27%) | 17 (9%) | 0.004 |

| Cigarette smoker | 15 (36%) | 90 (48%) | 0.22 |

| Systemic hypertension | 19 (46%) | 63 (34%) | 0.20 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 19 (46%) | 73 (39%) | 0.51 |

| Ejection fraction (mean (SD)) | 48.7 (6.3) | 49.1 (6.5) | 0.72 |

| Vessel score (mean (SD)) | 1.75 (1.0) | 1.4 (0.9) | 0.02 |

| Extent score (mean (SD)) | 68.3 (20) | 55.2 (16.7) | 0.0001 |

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate predictors of death and myocardial infarction

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Variable | χ2 | p Value | χ2 | p Value |

| Age | 18.5 | 0.0001 | 11.4 | 0.001 |

| Male sex | 2.3 | 0.12 | – | – |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.6 | 0.19 | – | – |

| Ejection fraction | 2.2 | 0.12 | – | – |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12.2 | 0.0001 | – | – |

| Cigarette smoker | 6.5 | 0.01 | – | – |

| Systemic hypertension | 2.1 | 0.14 | – | – |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 0.4 | 0.53 | – | – |

| Vessel score | 7.7 | 0.008 | – | – |

| Extent score | 13.4 | 0.0001 | 6.5 | 0.01 |

Survival analysis

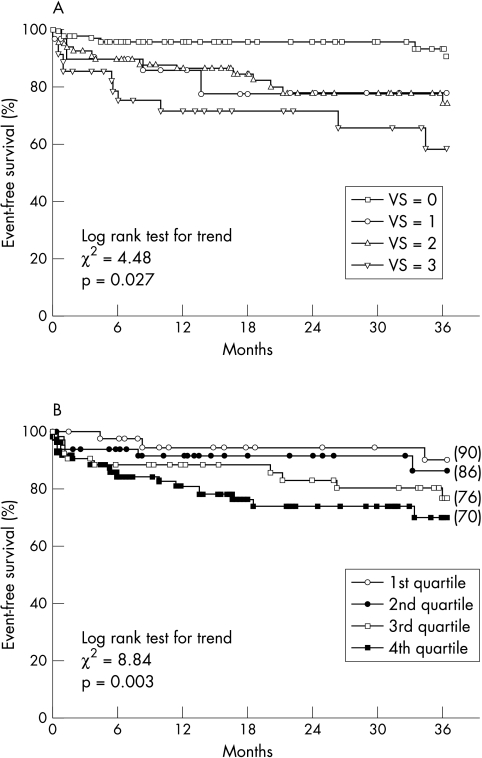

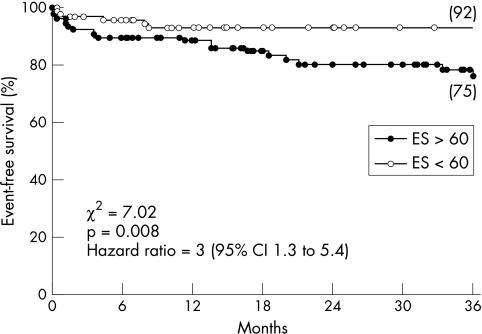

Kaplan–Meier event-free survival curves according to vessel and extent score are shown in fig 2. A vessel score of 3 was associated with a significantly worse survival (log rank χ2 for trend = 4.5, p = 0.027), but the overlap between group 1 and group 2 did not allow further prognostic classification. Conversely, the event rate increased significantly across ascending quartiles of extent score, providing a continuum for risk stratification. ROC curve analysis indicated 60 as the cut off value of extent score giving the best discrimination of risk (area under the curve = 0.70). The assignment of patients to two groups according to this value allowed significant discrimination of the event rate, even in cases with vessel scores of 0 to 2 (fig 3). This demonstrated the additional prognostic value of the extent score over the vessel score. In particular, six of the seven events occurring among the 29 patients with a vessel score of 0 were associated with extent score of ⩾ 60 and only one with an extent score of < 60 (χ2 = 4.8, p = 0.02; relative risk 8 (95% CI 1.2 to 57)).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier event-free survival curves according to vessel score (VS) (panel A) and extent score (by quartiles, panel B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier event-free survival curves in patients with vessel scores of 0 to 2, according to the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve derived cut off value for the extent score (ES).

Clinical correlates of extent score

The correlation between extent score and clinical variables is shown in table 3; age and diabetes were the only significant discriminators of a higher extent score.

Table 3.

Effect of individual clinical variables on extent score

| Variable | F | p Value |

| Age | 9.3 | 0.003 |

| Male sex | 0.28 | 0.59 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 0.39 | 0.53 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5.3 | 0.02 |

| Cigarette smoker | 1.2 | 0.26 |

| Systemic hypertension | 0.33 | 0.56 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 0.99 | 0.32 |

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that the diffusion of coronary atherosclerosis, assessed by the angiographic extent score, is a strong and independent predictor of adverse outcome, capable of providing additional prognostic information compared with clinical variables and the simple number of vessels with flow limiting stenoses. The calculation of per cent luminal diameter narrowing and the consequent classification of coronary artery disease according to the number of vessels showing flow limiting stenoses traditionally represents the preferred method of scoring coronary artery disease severity in both angiographic and prognostic13,14 studies. Although providing a convenient scheme in clinical practice, this method is limiting in that it includes patients with very different risk profiles and underestimates the importance of the overall coronary anatomy.15 The poor correlation between angiographic severity of coronary stenoses and the subsequent occurrence and location of vessel occlusion has been reported previously.16 It later became evident that most plaque ruptures or erosions complicated by occlusive thrombosis and resulting in acute coronary syndromes or sudden death occur at sites involving less than 50% lumen diameter narrowing.6,7 On the other hand, patients with non-occlusive lesions have significantly more cardiovascular events than those with truly normal angiograms.17 Recent studies showed that a sudden increase in pre-existing coronary stenoses, often associated with obvious changes in plaque morphology, can precede the onset of acute coronary syndromes18,19 and that the occurrence of acute myocardial infarction cannot be predicted from the severity of pre-existing stenoses.20 Unfortunately, serial angiographic studies showed that the progression of coronary artery disease in humans is neither linear nor predictable.4 New high grade lesions often appear in arterial segments that were normal only few months earlier, thus providing an explanation for the sudden progression of mild atherosclerosis to acute coronary events.

It has long been known that the angiographic severity of coronary lesions may not be the best reflection of the atherosclerotic process and its prognostic correlates.21 Ledru and colleagues sought to identify the angiographic predictors of future cardiac events and found that stenosis severity predicted only infarcts occurring within one year of angiography.22 Thus the identification of coronary lesions at high risk of occlusion remains challenging.23 At present there are few data on the morphology of vulnerable plaque in clinical settings and their prevalence in the general population. Yamagishi and colleagues reported that large eccentric plaques with features of a lipid-rich core can be at increased risk of instability even though the lumen area is preserved.24 Moreover, compensatory enlargement of the vessel wall because of remodelling25,26 can increase the risk of plaque rupture and acute luminal narrowing, although in this case angiography suggests a relatively small degree of stenosis with consequent underestimation of disease severity.

The extent score was significantly correlated with age and the presence of diabetes in our study. This is in keeping with the known pivotal role of diabetes as both a promoter of atherogenesis27 and as a prognostic determinant of cardiac morbidity and mortality.28 The extent score may thus reflect the chronically progressive component of atherosclerotic disease in the coronary circulation, which is not adequately addressed by angiographic variables that are simply related to stenosis severity.

Clinical implications

It is a major challenge in modern cardiology to develop a diagnostic method for identifying vulnerable plaques that could guide the physician in targeting intervention techniques to prevent acute vessel occlusion. Currently available tools do not allow one to identify serial changes marking the transition from stable to unstable plaques in humans, and from a disrupted plaque to an occlusive thrombus. Thus the evaluation of coronary artery disease severity remains the angiographic benchmark for patient management.29 The results of our study suggest that the extent score is a powerful marker of the risk of hard events independent of severity and even of the presence of flow limiting coronary lesions, and may reflect the link between clinical risk profile and diffusion of coronary atherosclerosis. Thus it could be of clinical value for targeting aggressive prevention measures whose beneficial effects on the progression and regression of coronary artery disease have been documented in clinical and angiographic studies.30–32

The non-invasive quantification of coronary artery calcification by electron beam computed tomography has recently been shown to provide important prognostic information and to be superior to coronary angiography in predicting future cardiac events.33 This finding is in keeping with our results and emphasises the close correlation between diffusion of coronary atherosclerosis and the likelihood of cardiac events. However, the angiographic assessment of vessel disease in that study relied only on per cent diameter narrowing; thus no correlation could be derived between invasive and non-invasive evaluation of the diffusion of coronary atherosclerosis.

Study limitations

As quantitative angiography was not available in all cases, the calliper technique was used for angiographic analysis; however, the diagnostic performance of the two techniques is known to be similar.9 Information on the haemodynamic importance of coronary stenosis by stress testing techniques was not evaluated. Finally, this study was conducted in patients who had coronary artery disease but in whom revascularisation was deferred. They therefore represent a lower risk population, and so our results cannot be extrapolated to other higher risk populations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammermeister KE, DeRouen TA, Dodge HT. Variables predictive of survival in patients with coronary disease: selection by univariate and multivariate analyses from clinical, electrocardiography, exercise, arteriographic, and quantitative angiographic evaluations. Circulation 1979;59:421–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seiler C, Kirkeeide RL, Gould KL. Basic structure–function relations of the coronary vascular tree. The basis of quantitative coronary arteriography for diffuse coronary artery disease. Circulation 1992;85:1987–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter TR, Sears T, Xie F, et al. Intravascular ultrasound study of angiographically mildly diseased coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:1858–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambrose JA, Tannenbaum MA, Alexopoulos D, et al. Angiographic progression of coronary artery disease and the development of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988;12:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Little WC, Costantinescu M, Applegate RJ, et al. Can coronary angiography predict the site of a subsequent myocardial infarction in patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery disease? Circulation 1988;78:1157–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiao JH, Fishbein MC. The severity of coronary atherosclerosis at sites of plaque rupture with occlusive thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;17:1138–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yokoya K, Takatsu H, Suzuki T, et al. Process of progression of coronary artery lesions from mild or moderate stenosis to moderate or severe stenosis: a study based on four serial coronary arteriograms per year. Circulation 1999;100:903–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan DR, Marwick TH, Freedman SB. A new method of scoring coronary angiograms to reflect extent of coronary atherosclerosis and improve correlation with major risk factors. Am Heart J 1990;119:1262–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalbfleisch SJ, McGillem MJ, Pinto IMF, et al. Comparison of automated quantitative angiography with caliper measurements of percent diameter stenosis. Am J Cardiol 1990;65:1181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pratt CM, Greenway PS, Schoenfeld MH, et al. Exploration of the precision of classifying sudden cardiac death: implication for the interpretation of clinical trials. Circulation 1996;93:519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottlieb SS. Dead is dead – artificial definitions are no substitute. Lancet 1997;349:662–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and the use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982;143:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mock MB, Ringquist I, Fisher LD, et al. Survival of medically treated patients in the Coronary Artery Surgery (CASS) registry. Circulation 1982;66:562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cosgrove DM, Loop FD, Sheldom WC. Results of myocardial revascularization: a 12 year experience. Circulation 1982;65(suppl II):II-37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seizer A. On the limitation of therapeutic intervention trials in ischemic heart disease: a clinician’s viewpoint. Am J Cardiol 1982;49:252–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hackett D, Davies G, Maseri A. Preexisting coronary stenoses in patients with first myocardial infarction are not necessarily severe. Eur Heart J 1988;9:1317–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emond M, Mock MB, Davis KB, et al. Long-term survival of medically treated patients in the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) registry. Circulation 1994;90:2645–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaski JC, Chester MR, Chen L, et al. Rapid angiographic progression of coronary artery disease in patients with angina pectoris. The role of complex stenosis morphology. Circulation 1995;92:2058–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ojio S, Takatsu H, Tanaka T, et al. Considerable time from the onset of plaque rupture and/or thrombi until the onset of acute myocardial infarction in humans. Circulation 2000;102:2063–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tousoulis D, Davies G, Crake T, et al. Angiographic characteristics of infarct-related and non infarct-related stenoses in patients in whom stable angina progressed to acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1998;136:382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutter AM. Is there a left main equivalent? Circulation 1980;62:207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledru F, Théroux P, Lespérance J, et al. Geometric features of coronary lesions favoring acute occlusion and myocardial infarction: a quantitative angiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuster V. Acute coronary syndrome: the degree and morphology of coronary stenoses. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:52–4B. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamagishi M, Terashima M, Awano K, et al. Morphology of vulnerable coronary plaque: insights from follow up of patients examined by intravascular ultrasound before an acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarius CK, et al. Compensatory enlargement of various human atherosclerotic coronary artery. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasterkamp G, Schoneveld AH, van der Wal AC. Relation of arterial geometry to luminal narrowing and histological markers for plaque vulnerability: the remodelling paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:655–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fagan TC, Deedwania PC. The cardiovascular dysmetabolic syndrome. Am J Med 1998;105:77–82S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janka HU. Increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in diabetes mellitus: identification of high risk factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract Suppl 1996;30:85–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan TJ, Bauman WB, Kennedy JW, et al. Guidelines for PTCA. A report of AHA/ACC task force on assessment of diagnostic and therapeutic cardiovascular procedures. Circulation 1993;88:2987–3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MAAS Investigators. Effect of simvastatin on coronary atheroma: the Multicentre Anti-Atheroma Study (MAAS). Lancet 1994;344:633–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitt B, Mancini GBJ, Ellis SG, et al. Pravastatin limitation of atherosclerosis in the coronary artery (PLAC I): reduction in atherosclerosis progression and clinical events. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26:1133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jukema JW, Bruschke AVG, van Boven AJ, et al. Effect of lipid lowering by pravastatin on the progression and regression of coronary artery disease in symptomatic men with normal to moderately elevated serum cholesterol levels. Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS). Circulation 1995;91:2528–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keelan PC, Bielak LF, Ashai K, et al. Long-term prognostic value of coronary calcification detected by electron-beam computed tomography in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Circulation 2001;104:412–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]