Abstract

A case of severe intractable angina pectoris with normal angiography is presented. Following video assisted thoracic sympathectomy the patient died of heart failure. Microvascular cardiac amyloidosis was diagnosed at the postmortem examination. This report alerts clinicians to this possible diagnosis when treating patients with severe angina when no cause is found and discusses the poor prognosis in such cases.

Keywords: amyloidosis, angina, coronary artery disease

Early amyloidosis without myocardial involvement can produce severe anginal symptoms by obstructing the intramural (rather than the epicardial) coronary arteries. The prognosis for this condition is poor.1 In a case series, five of 153 (3%) patients with angina and a normal coronary angiogram had small vessel disease secondary to amyloidosis.2 Another unrelated series found up to 30% of patients with anginal symptoms to have a normal coronary angiogram.3 The overall frequency of such amyloid related angina is unknown. However, we suggest that amyloid be considered in cases of severe angina that is not otherwise explicable.

CASE REPORT

A 65 year old non-smoking male retired squash coach presented with exertional dyspnoea. An exercise ECG showed myocardial ischaemia. He also developed a widespread inflammatory arthritis treated with sulfasalazine and methotrexate. Coronary angiography showed good left ventricular function and mild atheroma at the origin of the left anterior descending coronary artery, which would not be expected to cause angina even at extreme exertion. The exertional angina persisted and one year later an exercise test was also positive with major ST changes after only four minutes of the Bruce protocol. Repeat angiography showed the same minor stenosis. In addition, the coronary arteries were described as being mildly atheromatous and tortuous in keeping with hypertension. The patient’s angina continued to worsen despite maximum medical treatment with a β blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, calcium channel blocker, and oral nitrates. His first cardiologist sought a second opinion from a colleague, who thought that a combination of mild atheroma, spasm of the coronary arteries, and microvascular coronary disease could be causing the severe symptoms. The first cardiologist performed an angioplasty and stented the left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis. This did not relieve symptoms at all and the patient found his angina increasingly intolerable. He reached the stage where he was able to walk only a few yards without angina, which was also brought on by eating. The patient was referred to a thoracic surgeon to be considered for a sympathectomy. During consultation with the surgeon the patient again experienced angina at rest with ST depression. Very soon afterwards a chemical sympathectomy (stellate ganglion block) was performed with a good but temporary result and on this basis the patient proceeded to have a video assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) left sympathectomy. The left sympathetic chain was divided with diathermy over the necks of the second, third, and fourth ribs. Three hours after the procedure the patient suddenly developed respiratory failure (Po2 5.6 kPa and Pco2 3.1 kPa) with signs of pulmonary oedema. He was intubated, ventilated, and given an infusion of noradrenaline (norepinephrine) to maintain support. He was transferred to the intensive care unit that evening. The ECG remained normal. Troponin T was mildly increased (0.18 ng/ml, normal < 0.05 ng/ml). Echocardiogram showed mild global left ventricular dysfunction. Ventilation was continued for eight days in the intensive care unit without improvement. On the eighth postoperative day the patient became hypotensive and then asystolic and died. At necropsy pulmonary congestion and left ventricular scarring were found on gross examination. Histological examination of the heart and lungs found deposits of immunoglobulin light chain related (AL) amyloid within the walls of the smaller coronary and pulmonary arteries (fig 1). There was no amyloid in the epicardial coronary arteries and the myocardium. There was no atheroma in the epicardial coronary arteries, conflicting with the angiogram report.

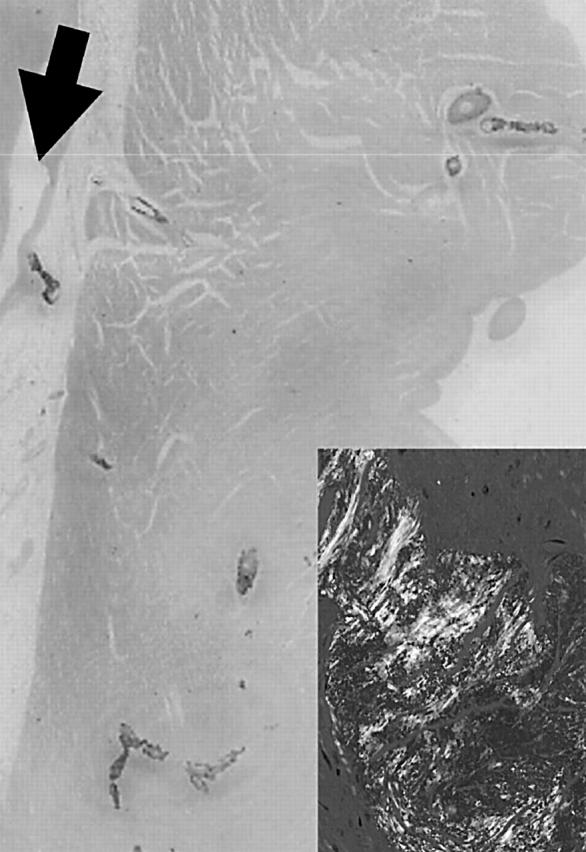

Figure 1.

Diffuse heavy deposits of Congo Red positive amyloid are seen in the intramyocardial coronary arteries; the epicardial mildly stenosed coronary artery branch (arrow) is itself free of amyloid. Inset shows green birefringence of vascular amyloid.

DISCUSSION

“Syndrome X” describes patients with angina of exertion, a positive exercise ECG, and a normal coronary angiogram, but excludes coronary artery spasm (Prinzmetal’s angina).3 It is a heterogeneous syndrome with several suggested mechanisms. “Microvascular angina” refers to all patients with angina, a normal angiogram, and evidence of impaired coronary microcirculation whether or not there are exercise induced ECG changes. Evidence would include impaired coronary flow reserve.

The most common form of amyloidosis is AL or primary amyloidosis. It results from the extracellular deposition of amyloid fibrillar protein by monoclonal plasma cells. Cardiac complications develop in most patients with amyloidosis and cause death in about 50%. Although congestive heart failure is the most common complication, obstructive intramural coronary artery amyloid deposition more rarely causes ischaemic symptoms. The epicardial coronary arteries are typically spared. Vascular involvement is more common in AL amyloid than other types.4 Although there have been previous reports of ischaemic syndromes with amyloidosis,1,2,5–8 we were unfamiliar with this association, and amyloid was not considered to be a possible antemortem diagnosis in the case described. An element of epicardial coronary spasm may have contributed to the ischaemia but there was no radiological evidence for this when the patient was experiencing pain during his second angiogram. All patients with obstructive intramural coronary artery amyloid deposition seem to have impaired coronary flow reserve.2,7

VATS sympathectomy has recently been evaluated as a treatment for severe angina untreatable by other means.9 Its aim is to improve symptoms and reduce ischaemia but the clinical results do not show a convincing benefit.

It is particularly important to diagnose amyloid in such cases of angina because prognosis of patients with intracoronary amyloid is reported to be extremely poor. In a case series of five, all patients developed congestive heart failure.2 In another series of 11 patients the mean time to death or transplantation after the onset of ischaemic symptoms was 18 months.1 Intervention to relieve symptoms is unlikely to alter this prognosis. In the case described in this report a diagnosis of amyloid could possibly have been made if a skin, rectal, lung, or myocardial biopsy had been taken. Knowing the diagnosis of amyloid would alert the attending clinicians to the poor prognosis, and interventional treatment such as VATS sympathectomy may be avoided. Chemotherapeutic regimens are available for treating primary amyloidosis and may be of more benefit. Cardiac transplantation may be another option.10

Acknowledgments

The advice given by Professor Tom Treasure in preparing the manuscript is gratefully acknowledged.

D C Whitaker is the guarantor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mueller PS, Edwards WD, Gertz MA. Symptomatic ischemic heart disease resulting from obstructive intramural coronary amyloidosis. Am J Med 2000;109:181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suwaidi JA, Velianou JL, Gertz MA, et al. Systemic amyloidosis presenting with angina pectoris. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:838–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaski JC, Elliott PM. Angina pectoris and normal coronary arteriograms: clinical presentation and hemodynamic characteristics. Am J Cardiol 1995;76:35–42D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crotty TB, Li C, Edwards WD, et al. Amyloidosis and endomyocardial biopsy: correlation of extent and pattern of deposition with amyloid phenotype in 100 cases. Cardiovasc Pathol 1995;4:39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishikawa Y , Ishii T, Masuda S, et al. Myocardial ischaemia due to vascular systemic amyloidosis: a quantitative analysis of autopsy findings on stenosis of the intramural coronary arteries. Pathol Int 1996;46:189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miani D , Rocco M, Alberti E, et al. Amyloidosis of epicardial and intramural coronary arteries as an unusual cause of myocardial infarction and refractory angina pectoris. Ital Heart J 2002;3:479–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogawa H , Mizuno Y, Ohkawara S, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis presenting as microvascular angina: a case report. Angiology 2001;52:273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen EC, Engel JA, Radio SJ, et al. The clinical problem of occult cardiac amyloidosis: forensic implications. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1992;13:225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khogali SS, Miller M, Rajesh PB, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic sympathectomy for severe intractable angina. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;16:S95–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelosi F Jr, Capehart J, Roberts WC. Effectiveness of cardiac transplantation for primary (AL) cardiac amyloidosis. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:532–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]