A new cardiac syndrome exhibiting transient left ventricular (LV) apical ballooning has been widely described in Japan. Conversely, there are few series outside Japan.1,2 This syndrome usually affects elderly women, frequently preceded by emotional/physical stress.1,2 These patients present with chest pain, ECG abnormalities, and minimal enzymatic release, mimicking an anterior wall acute coronary syndrome (ACS). LV contractility recovers in several days. Today, the aetiology remains unknown. Systematically, coronary artery disease (CAD) has been ruled out because of the wide akinetic area and absence of significant coronary artery stenosis on angiography. Recently we have published that tako-tsubo patients have a well developed left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, suggesting that the akinetic area could be supplied by LAD alone.1

To test the hypothesis that a ruptured coronary plaque could be the underlying aetiology of this syndrome we prospectively performed intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) examination in five consecutive tako-tsubo patients.

METHODS

From May 2003 to February 2004 we identified five patients fulfilling the following criteria: suspected ACS based on chest pain, ECG changes, and enzymatic release; transient LV apical ballooning; absence of stenosis > 50% in all major coronary arteries. All five patients underwent a LV angiographic and coronariographic examination. Mean (SD) time to angiography was 20.2 (12.0) hours (range 5–36 hours) after the onset of symptoms. We measured the length of the LAD in the left lateral projection, from left coronary ostium to its end, by tracing the actual course of the artery. We have termed the most distant spot of the vessel in relation to the left coronary ostium the LAD apical point. We define the LAD recurrent segment as the portion of vessel from the latter apical point to the most distal visible end of the artery. This segment irrigates the diaphragmatic LV wall. To normalise the measurements of LAD recurrent segment we designed a LAD recurrent segment index: [LAD recurrent segment length/total LAD length] × 100.

After glyceryl trinitrate administration, an IVUS transducer was placed at the distal portion of the LAD and automatic pull back was carried out at 0.5 mm/s. Vessel characteristics were analysed by three blinded experts.

Cross sectional images were quantified for lumen cross sectional area (LCSA, mm2), external elastic membrane (EEM), and plaque burden (PB); the PB was calculated using the following equation: PB = [EEM CSA−LCSA]/EEM CSA × 100.

Morphological analysis of coronary plaques included fibrous capsule rupture with or without intraplaque cavity, ulceration by atheromatous extrusion without visible capsule, and plaque dissection.

RESULTS

All five patients were women; mean age: 77 (5) years (71–83). Four patients referred to emotional/physical stress before onset of symptoms. All had abnormal troponin I (TnI) concentrations: mean (SD) TnI 3.7 (2.6) ng/ml (range 1.37–7.47 ng/ml), without creatine phosphokinase concentrations above normal limits. Ventriculography revealed a LV tako-tsubo-like apical ballooning, a form of systolic LV dysfunction characterised by a wide apical akinesia with preserved or hyperkinetic basal segments. Complete normalisation of systolic LV function was observed in all patients within 7 (3) days (range 4–12 days). Early coronary arteriography showed no epicardial narrowing > 50% and normal flow in all coronaries in all patients.

Total LAD length was 133.6 (13.3) mm (range 117.7–147.4 mm). The LAD in all patients bent around the LV apex, extending along the diaphragmatic LV aspect. The length of the LAD recurrent segment was 30.4 (4.3) mm (range 25.7–34.9 mm). The LAD recurrent segment index was 22.7 (1.3)% (range 20.8–24.0%).

In all five cases, IVUS showed a single, ruptured, atherosclerotic plaque in the middle portion of the LAD, without any other atherosclerotic disease in the rest of the vessel; three cases with fibrous capsule rupture and intraplaque cavity, one case with fibrous capsule rupture without ulceration, and one case with an intimal dissection flap.

LCSA in the five patients was 9.1 mm2, 6.6 mm2, 7.5 mm2, 8.8 mm2, and 9.3 mm2, while PB was 22.5%, 45%, 42.5%, 28.5%, and 24.6% respectively.

DISCUSSION

Since the initial description of this syndrome, several aetiologies have been postulated. There is general consensus considering tako-tsubo syndrome as a form of myocardial stunning, however its aetiology remains unclear. All signs and symptoms point to an ACS, however CAD has been systematically ruled out, based on two features: firstly, early angiography showed no significant luminal stenosis; and secondly, a large akinetic area, an area so extensive that previous authors have suggested it does not correspond to the perfusion territory of a single coronary artery.2 In our institution, we observed that all tako-tsubo patients had an LAD with a large diaphragmatic course,1 suggesting that all LV akinetic areas could be supplied by the LAD alone. The absence of significant coronary artery stenosis in tako-tsubo patients does not exclude the existence of CAD, because of the limitations of coronary angiography. Nissen and colleagues3 reported that coronary plaques responsible for ACS frequently show positive remodelling and are not easily diagnosed by coronary angiography when a thrombus has been resolved.

The high incidence of stress before the onset of symptoms (in our series 80%), led to suggestions of the involvement of catecholamines in the syndrome pathogenesis. Acute stress has been associated with raised pro-inflammatory cytokines and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) concentrations, both of which induce vasoconstriction and elevated blood pressure, thus making a vulnerable plaque prone to rupture.4

ACS results from the abrupt thrombus formation within a coronary artery. An accepted triggering mechanism for intracoronary thrombosis is the rupture, fissuring, or erosion of an atheromatous plaque which exposes the lipid core to the vessel lumen and is followed by platelet adhesion and aggregation and subsequent thrombosis. Spontaneous intermittent coronary recanalisation and reocclusion resulting from a variable combination of thrombosis and vasoconstriction are frequent during the early phase of ACS.5 Transient coronary artery occlusion/reperfusion episodes may lead to myocardial stunning and akinesia of the myocardium supplied by the coronary artery. When occlusion episodes are short enough, release of blood markers of myocardial ischaemia and necrosis is minimal with total recovery of cardiac function.

In all five of our tako-tsubo patients, the LAD coronary artery had a long course around the LV apex, supplying an extensive portion of the diaphragmatic LV aspect. This particular LAD anatomy could explain the peculiar morphology adopted by the LV during systole; the LAD corresponds well with the areas showing akinetic systolic behaviour.

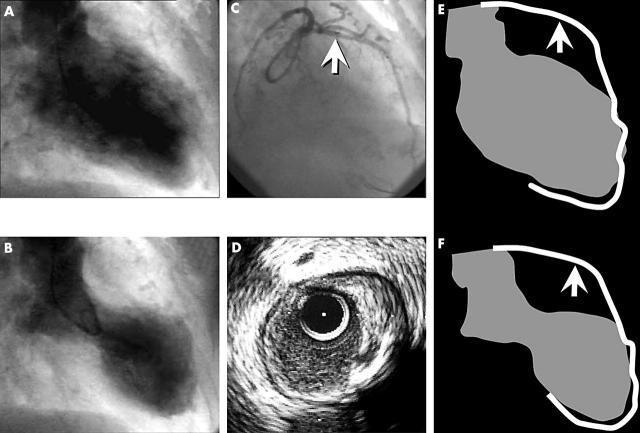

In this study we prospectively describe for the fist time the IVUS features of the LAD in tako-tsubo patients. In all cases a disrupted atherosclerotic plaque was found. The characteristics of the plaques suggest they are unstable. Our findings could explain the pathophysiology of tako-tsubo syndrome as being the presence of a ruptured plaque in the middle portion of a well developed LAD, supplying a vast LV territory (fig 1). The disruption of that plaque could lead to an ACS with early reperfusion, and thus minimal enzymatic release and LV stunning rather than necrosis.

Figure 1.

(A) End diastolic frame of the LV angiogram in right anterior oblique (RAO) 30° projection. (B) End systolic frame—note the wide apical akinesia (ballooning). (C) RAO 30° projection of left coronary artery; the arrow shows the IVUS transducer placement. (D) Cross sectional IVUS view of LAD, showing a disrupted eccentric plaque with positive remodelling from 12 to 5 o’clock. At 4 o’clock there is an image of ulceration, with a cavity inside the plaque. The cavity is located just beside a calcification zone (acoustic shadow from 4 to 6 o’clock). Panels E (diastole) and D (systole) are a schematic representation of the LAD and LV in RAO 30°; the arrow shows the ruptured plaque location. Note that the akinetic area corresponds to the LV area between the plaque and the end of LAD.

From these findings we hypothesise that, in some tako-tsubo patients, the underlying cause of this enigmatic syndrome is an ACS with early reperfusion and wide LV stunned myocardium.

Abbreviations

ACS, acute coronary syndrome

CAD, coronary artery disease

EEM, external elastic membrane

IVUS, intravascular ultrasound

LAD, left anterior descending

LCSA, lumen cross sectional area

LV, left ventricular

PB, plaque burden

RAO, right anterior oblique

TnI, troponin I

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibanez B, Navarro F, Farre J, et al. “Tako-tsubo” transient left ventricular apical ballooning is associated with a left anterior descending coronary with a long course along the apical diaphragmatic surface of the left ventricle. Rev Esp Cardiol 2004;57:209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desmet WJ, Adriaenssens BF, Dens JA. Apical ballooning of the left ventricle: first series of white patients. Heart 2003;89:1027–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nissen SE. Pathobiology, not angiography, should guide management in acute coronary syndrome/non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:103S–12S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gidron Y, Gilutz H, Berger R, et al. Molecular and cellular interface between behavior and acute coronary syndromes. Cardiovasc Res 2002;56:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hackett D, Davies G, Chierchia S, et al. Intermittent coronary occlusion in acute myocardial infarction. Value of combined thrombolytic and vasodilator therapy. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1055–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]