Abstract

Background: We have previously shown that the non-selective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor indomethacin retards recovery of intestinal barrier function in ischaemic injured porcine ileum. However, the relative role of COX-1 and COX-2 elaborated prostaglandins in this process is unclear.

Aims: To assess the role of COX-1 and COX-2 elaborated prostaglandins in the recovery of intestinal barrier function by evaluating the effects of selective COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors on mucosal recovery and eicosanoid production.

Methods: Porcine ileal mucosa subjected to 45 minutes of ischaemia was mounted in Ussing chambers, and transepithelial electrical resistance was used as an indicator of mucosal recovery. Prostaglandins E1 and E2 (PGE) and 6-keto-PGF1α (the stable metabolite of prostaglandin I2 (PGI2)) were measured using ELISA. Thromboxane B2 (TXB2, the stable metabolite of TXA2) was measured as a likely indicator of COX-1 activity.

Results: Ischaemic injured tissues recovered to control levels of resistance within three hours whereas tissues treated with indomethacin (5×10−6 M) failed to fully recover, associated with inhibition of eicosanoid production. Injured tissues treated with the selective COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 (5×10−6 M) or the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 (5×10−6 M) recovered to control levels of resistance within three hours, associated with significant elevations of PGE and 6-keto-PGF1α compared with untreated tissues. However, SC-560 significantly inhibited TXB2 production whereas NS-398 had no effect on this eicosanoid, indicating differential actions of these inhibitors related to their COX selectivity.

Conclusions: The results suggest that recovery of resistance is triggered by PGE and PGI2, which may be elaborated by either COX-1 or COX-2.

Keywords: prostaglandins, barrier function, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, indomethacin

The principal pharmacological target of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is cyclooxygenase (COX), the enzyme responsible for the production of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid.1 The finding that NSAIDs can induce gastrointestinal mucosal ulceration in patients with no underlying intestinal disease implies that prostaglandins play a vital physiological role in maintaining the integrity of the gastrointestinal mucosa.2 In fact, there is considerable evidence to support a cytoprotective role for prostaglandins in the gut.3–5 In addition to maintenance of the mucosal barrier, recent experimental studies indicate that certain prostaglandins stimulate reparative mechanisms in injured gastrointestinal epithelium.6–8

There are two known isoforms of COX: COX-1, which is expressed constitutively in gastrointestinal mucosa,9 and COX-2, which is expressed primarily in response to inflammatory stimuli.10 However, the relative roles of COX-1 and COX-2 in the elaboration of prostaglandins involved in pathophysiological events such as epithelial repair are unclear. For example, mucosal healing was impaired in mice with experimentally induced gastric mucosal ulcers treated with the selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-3989 despite the fact that COX-1 was originally credited with producing cytoprotective prostaglandins.11 The creation of COX-1 and COX-2 null mice would seem to be the ultimate methodology to discern the relative roles of COX-1 and COX-2 in the maintenance and restoration of mucosal barrier function. However, this approach has to some extent clouded this issue because knockout of either COX-1 or COX-2 may result in compensatory increases in prostaglandin E1 and E2 (PGE) production from the remaining COX isoform.12 This in turn may explain unexpected findings such as the reduced susceptibility of COX-1 knockout mice to indomethacin induced gastric ulceration.13

It has been suggested that valid interpretations of the roles of COX-1 and COX-2 in epithelial repair in wild-type animals may be gained from direct comparisons between COX-2 inhibitors and conventional NSAIDs such as indomethacin.14 Thus we chose to compare the effects of selective and non-selective COX inhibitors in a porcine model of mucosal recovery in which we have previously demonstrated an inhibitory role of indomethacin.6 In the present studies, we compared the effects of indomethacin with the effects of the selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-3989,15 and the selective COX-1 inhibitor SC-56016,17 on recovery of mucosal barrier function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animal surgeries

All studies were approved by the North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were 6–8 week old crossbred (Duroc×Yorkshire×Landrace) pigs of both sexes purchased from North Carolina State University Porcine Educational Unit. Animals were acclimatised to the holding facilities at the College of Veterinary Medicine for at least three days. Pigs were housed singularly and maintained on a commercial pelleted feed. Pigs were held off feed for 24 hours prior to experimental surgery. All experiments were performed by the same team to minimise variability. A physical examination was performed on all animals by veterinary investigators (Blikslager, Zimmel) to ensure the good health of the animals on the day of experimental surgery. General anaesthesia was induced with xylazine (1.5 mg/kg intramuscularly), ketamine (11 mg/kg intramuscularly), and pentobarbital (15mg/kg intravenously) and was maintained with intermittent infusion of pentobarbital (6–8 mg/kg/h). Pigs were placed on a heating pad and ventilated with 100% O2 via a tracheotomy using a time cycled ventilator. The jugular vein and carotid artery were cannulated, and blood gas analysis was performed to confirm normal pH, and partial pressures of CO2 and O2. Lactated Ringer's solution was administered intravenously at a maintenance rate of 15 ml/kg/h. Blood pressure was continuously monitored via a transducer connected to the carotid artery. The ileum was approached via a ventral midline incision. Ileal segments were delineated by ligating the intestinal lumen at 10 cm intervals, and subjected to ischaemia by clamping the local mesenteric blood supply for 45 minutes. Following the ischaemic period, pigs were killed and intestinal loops were resected.

Ussing chamber studies

The mucosa was stripped from the seromuscular layer in oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) Ringer's solution, and mounted in 3.14 cm2 aperture Ussing chambers, as described in previous studies.18 Tissues were bathed on the serosal and mucosal sides with 10 ml Ringer's solution. The serosal bathing solution contained 10 mM glucose and was osmotically balanced on the mucosal side with 10 mM mannitol. Bathing solutions were oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) and circulated in water jacketed reservoirs. The spontaneous potential difference (PD) was measured using Ringer-agar bridges connected to calomel electrodes, and PD was short circuited through Ag-AgCl electrodes using a voltage clamp that corrected for fluid resistance. Transepithelial resistance (Ω×cm2) was calculated from spontaneous PD and short circuit current (Isc). If spontaneous PD was between −1.0 and 1.0 mV, tissues were current clamped at ±100 μA for five seconds and the PD recorded. Isc and PD were recorded every 60 minutes for 240 minutes.

Chemicals

Tissues treated with COX inhibitors were bathed in Ringer's containing the appropriate concentration of indomethacin (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, Missouri, USA), NS-398 (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, California, USA), or SC-560 (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) to prevent prostaglandin production while stripping mucosa from the seromuscular tissues. The appropriate COX inhibitors were also added to the serosal and mucosal bathing solutions prior to mounting tissues in Ussing chambers.

Eicosanoid analyses

Samples were taken from the serosal bathing solutions of tissues after 60 minutes and 240 minutes of the experiment and were immediately frozen in liquid N2. Samples were stored at −70°C prior to eicosanoid analysis. Samples were analysed for concentrations of PGE, 6-keto-PGF1α (the stable metabolite of prostaglandin I2 (PGI2)), and thromboxane B2 (TXB2, the stable metabolite of TXA2) using commercial ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Biomedical Technologies Inc., Stoughton, Massachusetts, USA).

Morphometric measurements

Tissues were taken immediately after ischaemia and following the 240 minute recovery period for histological evaluation. Tissues were sectioned (5 μm) and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. For each tissue, three sections were evaluated by an investigator blinded to the treatment group. Four well oriented villi were identified in each section. Morphometric measurements were performed as previously described.19 The height of the villus, and the width at the midpoint of the villus, were obtained using a light microscope with an ocular micrometer. In addition, the height of the epithelial covered portion of each villus was measured. The surface area of the villus was calculated using the formula for the surface area of a cylinder. The formula was modified by subtracting the area of the base of the villus, and multiplying by a factor accounting for the variable position at which each villus was cross sectioned. In addition, the formula was modified to take into account the hemispherical nature of the villous tip.19 The percentage of the villous surface area that remained denuded was calculated from the total surface area of the villus and the surface area of the villus covered by epithelium. Per cent denuded villous surface area was used as an index of epithelial restitution.6

Isotope flux studies

To assess mucosal to serosal flux of mannitol, 0.2 μCi/ml of [3H]mannitol was added to the mucosal solution of tissues. Following a 15 minute equilibration period, standards were taken from the bathing reservoirs. Subsequently, three one hour fluxes were performed by taking samples from the serosal bathing reservoirs. Samples were collected in scintillation vials and assessed for β emission (counts/minutes). Mucosal to serosal fluxes of mannitol (Jms) were determined using standard equations.20

Gel electrophoresis and western blotting

Control and ischaemic injured mucosa was stripped in oxygenated Ringer's solution containing either no treatment or indomethacin, as described for the Ussing chamber experiments. Approximately half of each piece of tissue was then snap frozen whereas the remaining tissue was recovered for 240 minutes in oxygenated Ringer's prior to snap freezing. Tissues were stored at −70°C prior to preparation for sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), at which time they were thawed to 4°C. Tissue portions (1 g) were added to 3 ml of chilled RIPA buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.2), 1% deoxycholic acid, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS), including protease inhibitors. The mixture was homogenised on ice, centrifuged at 4°C, and the supernatant saved. Protein analysis of extract aliquots was performed (DC protein assay; Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). Tissue extracts (amounts equalised by protein concentration) were mixed with an equal volume of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled for four minutes. Lysates were loaded on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresis was carried out according to standard protocols. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond ECL; Amersham Life Science, Birmingham, UK) using an electroblotting minitransfer apparatus according to the manufacturer's protocol. Membranes were blocked at room temperature for 60 minutes in Tris buffered saline plus 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) and 5% dry powered milk. Membranes were washed twice with TBST and incubated for one hour in primary antibody (COX-1 or COX-2, affinity purified goat polyclonal antibodies; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, California, USA). After washing three times for 10 minutes each with TBST, membranes were incubated for 45 minutes with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody. After washing three additional times for 10 minutes each with TBST, the membranes were developed for visualisation of protein using an alkaline phosphatase conjugate substrate kit (Bio-Rad).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely processed for paraffin embedding, and cut into 5 μm sections. Following placement on slides, sections were deparaffinised and rehydrated. Slides were subsequently incubated in 3% H2O2, washed, and subjected to pronase digestion for 10 minutes. Slides were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with normal goat serum (Biogenex, San Ramon, California, USA) for 20 minutes. Slides were then incubated for one hour with either rabbit antisheep COX-1 polyclonal antibody or rabbit antihuman COX-2 polyclonal antibody (Alexis Co., San Diego, California, USA). This step was not performed on negative control slides. Slides were washed four times in PBS between 20 minute incubations with biotinylated goat antirabbit antibody and streptavidin labelled peroxidase (Biogenex). Slides were then placed in 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole, washed in distilled water, counterstained with 0.5% methyl green for 30 seconds, and mounted.

Data analysis

All data were analysed using a statistical software package (Sigmastat; Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, California, USA). Data are reported as mean (SEM) for a given number (n) of animals for each experiment. The statistical significance level selected for all tests was p<0.05. Prior to ANOVA, data were analysed to determine if they were normally distributed and had equal variance (Levene median test). If data failed either of these analyses, ANOVA on ranks was performed. All data were analysed using one way ANOVA at each time point to determine if there were statistically significant differences between treatments. Tukey's test was used to determine differences among treatments following ANOVA, unless ANOVA on ranks was performed, in which case a Student-Newman-Keuls test was performed.

RESULTS

Effect of COX inhibitors on recovery of mucosal resistance, permeability, and morphology

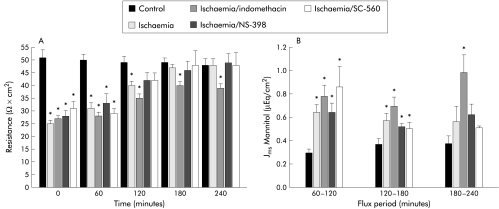

Ischaemic injured porcine ileum recovered to control levels of transepithelial electrical resistance (R) within 180 minutes whereas R in ischaemic injured tissues treated with the non-selective COX inhibitor indomethacin (5×10−6 M) remained below that of control levels throughout the experiment (fig 1A ▶). In contrast, the selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-3989 (5×10−6 M) or the selective COX-1 inhibitor SC-56016,17 (5×10−6 M) did not impair recovery of R compared with ischaemic controls. Similarly, mucosal to serosal fluxes of mannitol, a relatively small macromolecule (4 Å stokes radius) that traverses tissues via the paracellular space,21,22 decreased to control levels in untreated ischaemic injured tissues and in tissues treated with NS-398 or SC-560 within 180 minutes, whereas in tissues treated with indomethacin, mannitol fluxes remained significantly elevated above control levels for the duration of the 240 minute recovery period (fig 1B ▶).

Figure 1.

(A) Electrical responses of ischaemic injured porcine ileal mucosa to treatment with cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors. Forty five minutes of ischaemia resulted in baseline transepithelial resistance (R) ∼50% that of control. Untreated ischaemic injured tissues recovered control levels of R within 180 minutes whereas tissues treated with the non-selective COX inhibitor indomethacin (5×10−6 M) did not fully recover. However, ischaemic injured tissues treated with the selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 (5×10−6 M) or selective COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 (5×10−6 M) recovered levels of R not significantly different from control within three hours. *p<0.05 versus control. Significance was determined by one way ANOVA, n=12. (B) Mucosal to serosal fluxes (Jms) of mannitol across control and ischaemic injured tissues during a 240 minute recovery period. Jms mannitol in ischaemic injured tissues was significantly greater than control during the first flux period (60–120 minutes) regardless of treatment. While Jms mannitol recovered to levels not significantly different from control by 240 minutes in untreated ischaemic injured tissues or those treated with NS-398 (5×10−6 M) or SC-560 (5×10−6 M), Jms mannitol in indomethacin treated tissues remained greater than control levels throughout the recovery period. *p<0.05 versus control tissues. Significance was determined using one way ANOVA, n=8.

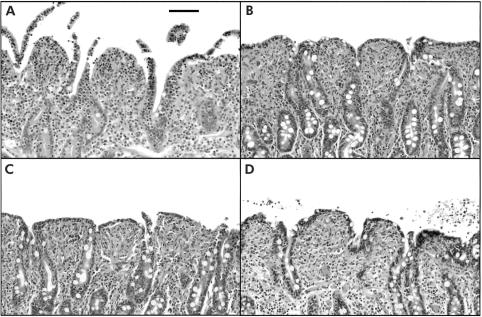

Histological evaluation of tissues immediately following the 45 minute ischaemic period revealed sloughing of villous tips (fig 2A ▶) which amounted to denudation of 16.5 (2.2)% of the villous surface area. Blinded evaluation of tissues at the end of the 240 minute recovery period showed 0.0 (0.0)% denudation as a result of epithelial restitution, regardless of treatment (fig 2B ▶–D). The degree of villous contraction was not significantly different among treatment groups (data not shown). Treatment of control tissues with COX inhibitors had no significant effect on R levels or histological appearance of tissues over the 240 minute recovery period (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Histological appearance of ischaemic injured porcine ileal mucosa. (A) Ischaemia for 45 minutes resulted in lifting and sloughing of epithelium from the tips of villi. (B) After a 240 minute in vitro recovery period, villi contracted and epithelial restitution was complete. (C) Treatment of tissues with indomethacin (5×10−6 M) had no observable effect on restitution in tissues recovered in vitro for 240 minutes. (D) Similarly, tissues treated with NS-398 (5×10−6 M) had evidence of villous contraction and complete epithelial restitution. 1 cm bar=100 μm.

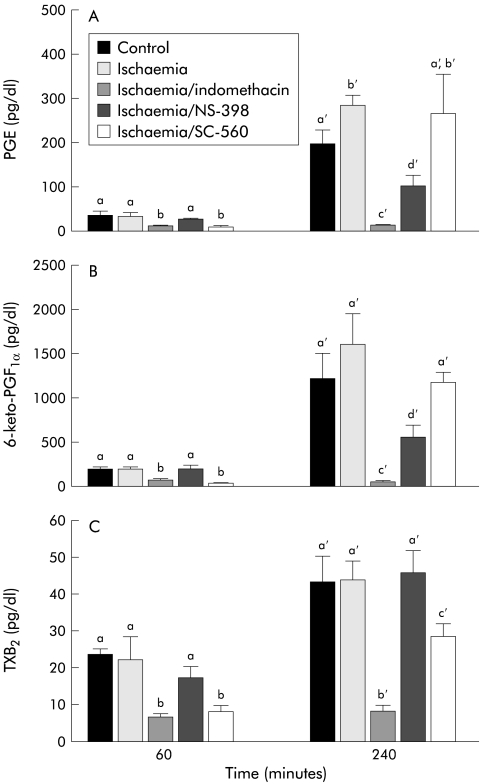

Eicosanoid levels in COX inhibitor treated tissues

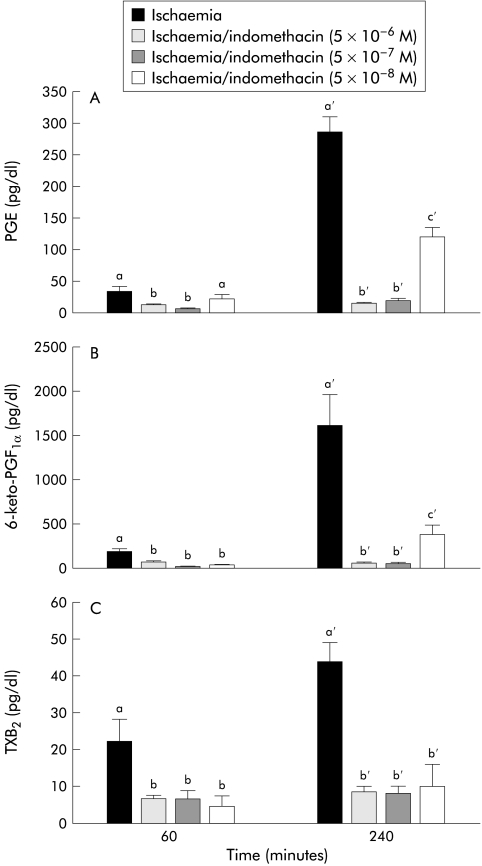

To determine if the differences in recovery of R and permeability shown with indomethacin, NS-398, or SC-560 could be associated with a different profile of eicosanoid production, we measured tissue production of PGE, 6-keto-PGF1α (the stable metabolite of PGI2), and TXB2 (the stable metabolite of TXA2). The latter has been used as a specific indicator of COX-1 activity in platelets23 and whole blood.24,25 As shown in fig 3A ▶, indomethacin and SC-560 inhibited all three eicosanoids at the first time period (60 minutes) whereas NS-398 had no inhibitory effect at this time. By the 240 minute measurement period there were marked elevations in all three eicosanoids in control and ischaemic injured tissues. However, treatment with 5×10−6 M indomethacin essentially eliminated production of all three eicosanoids whereas the same dose of the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 only partially inhibited production of PGE and 6-keto-PGF1α and had no inhibitory effect on TXB2 production. In contrast with these results, the selective COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 did not significantly inhibit PGE or 6-keto-PGF1α at 240 minutes but significantly inhibited TXB2 production.

Figure 3.

Eicosanoid levels in control and ischaemic injured tissues before and after a 240 minute recovery period. (A) Prostaglandin E1 and E2 (PGE) levels were significantly reduced at the 60 minute time period by indomethacin and SC-560. PGE levels were significantly higher in ischaemic injured tissues at 240 minutes compared with control tissues. Tissues treated with NS-398 had significant reductions compared with untreated tissues whereas SC-560 had no significant effect on PGE production at 240 minutes. (B) 6-keto-PGF1α (the stable metabolite of prostaglandin I2 (PGI2)) levels showed trends similar to those of PGE levels, including significant inhibition at 240 minutes by indomethacin and NS-398. (C) Levels of thromboxane B2 (TXB2, the stable metabolite of TXA2) were measured as a potential indicator of COX-1 activity. Accordingly, TXB2 levels were elevated to the same degree in control tissues, ischaemic injured tissues, and tissues treated with the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 at both time periods. However, tissues treated with indomethacin had no significant elevations in TXB2 during the recovery period, and tissues treated with SC-560 had levels significantly below those of untreated tissues at both 60 minutes and 240 minutes. Significance was determined using one way ANOVA at each time period, n=8. Treatments with different letters at each time period were significantly different from one another.

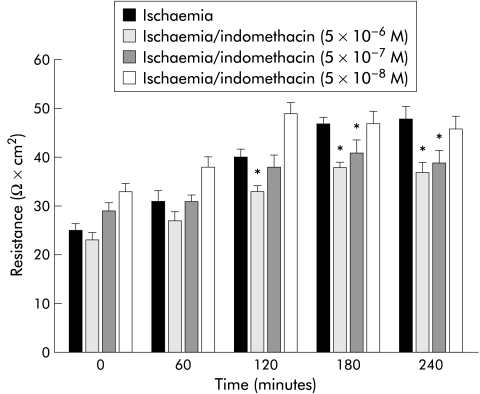

Response to varying doses of indomethacin and NS-398

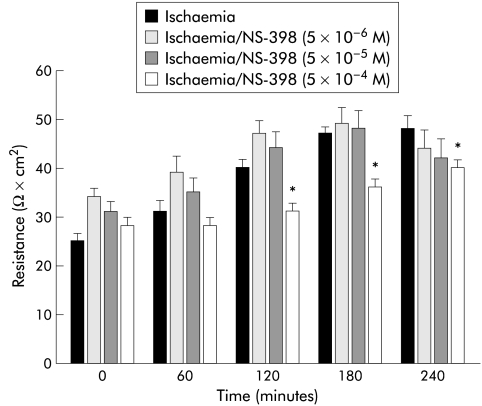

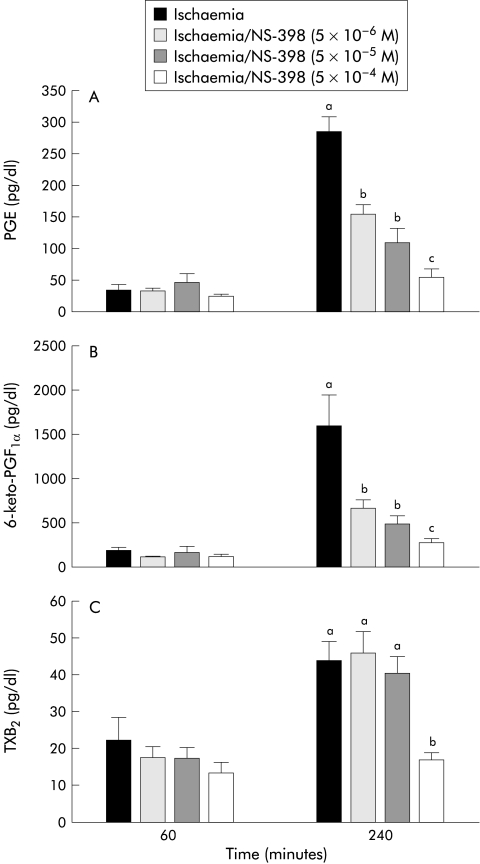

The results shown in fig 3 ▶ suggested that the differences in eicosanoid production in the presence of the different COX inhibitors might be due to a relative difference in sensitivity of the two COX enzymes to the inhibitors. To test this possibility, we performed experiments in which the doses of indomethacin or NS-398 were serially diluted or concentrated, respectively. Although a 10-fold dilution of indomethacin (5×10−7 M) inhibited recovery of R to the same extent as the original dose, a 100-fold dilution (5×10−8 M) permitted tissues to recover to levels similar to those of untreated ischaemic injured tissues (fig 4 ▶). This recovery of R at the 100-fold dilution of indomethacin correlated with significant elevations in PGE and 6-keto-PGF1α production measured at 240 minutes of recovery (fig 5B ▶, C). In contrast, no significant elevation in TXB2 production at any dose of indomethacin was obtained. In the converse experiment with NS-398, a 10-fold greater concentration (5×10−5 M) had no inhibitory effect on recovery of R (fig 6A ▶) and no additional effect on eicosanoid production (fig 7 ▶) whereas a 100-fold increase in concentration of NS-398 (5×10−4 M) inhibited recovery of R and completely inhibited production of all three eicosanoids.

Figure 4.

Electrical responses of ischaemic injured porcine ileal mucosa to varying doses of indomethacin. Tissues treated with either 5×10−6 M or 5×10−7 M indomethacin had levels of transepithelial electrical resistance (R) that remained significantly below untreated ischaemic tissue levels throughout the recovery period whereas tissues treated with 5×10−8 M indomethacin recovered to the same extent as untreated ischaemic tissues. *p<0.05 versus untreated ischaemic tissues. Significance was determined by one way ANOVA following two way ANOVA on repeated measures, n=8.

Figure 5.

Elaborated eicosanoid levels in response to varying doses of indomethacin. Prostaglandin E (PGE) (A) and 6-keto-PGF1α (B) levels were significantly elevated in tissues treated with 5×10−8 M indomethacin but fully inhibited by 5×10−6 M and 5×10−7 M indomethacin. (C) There were no significant elevations in thromboxane B2 (TXB2) regardless of the dose. *p<0.05 versus control tissue at 60 minutes. Treatments with different letters at 240 minutes were significantly different from one another. Significance was determined using one way ANOVA, n=8.

Figure 6.

Electrical responses of ischaemic injured porcine ileal mucosa to varying doses of NS-398. Tissues treated with 5×10−4 M NS-398 had significantly depressed levels of transepithelial electrical resistance (R) compared with tissues treated with either 5×10−5 M or 5×10−6 M NS-398. *p<0.05 versus untreated ischaemic tissues. Significance was determined using one way ANOVA, n=8.

Figure 7.

Elaborated eicosanoid levels in response to varying doses of NS-398. Production of prostaglandin E (PGE) (A), 6-keto-PGF1α (B), and thromboxane B2 (TXB2) (C) was nullified by treatment with 5×10−4 M NS-398 compared with treatment with lower doses of NS-398. Treatments with different letters were significantly different from one another. Significance was determined with one way ANOVA, n=8.

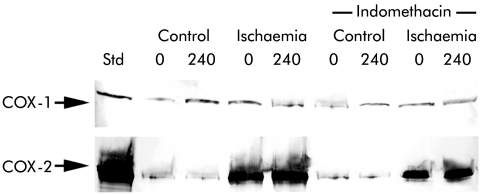

COX western blots

Although the above experiments suggested that a difference in sensitivity of COX-1 and COX-2 for the inhibitors could exist, possible changes in the concentration of active enzyme during the 240 minutes of the experiment could make such an interpretation difficult. Therefore, the relative concentrations of COX-1 and COX-2 protein were determined by western blot on control and ischaemic injured tissues prior to and following the 240 minute recovery period. COX-1 protein levels were similar in control and ischaemic injured tissues prior to recovery (0 minutes; fig 8 ▶). COX-1 protein levels appeared slightly elevated in control tissues following the recovery period (240 minutes) whereas there were no detectable elevations in COX-1 levels in ischaemic injured tissues. Treatment with indomethacin did not appear to have any apparent effect on COX-1 protein (fig 8 ▶). Western blot for COX-2 revealed evidence for some COX-2 protein in control tissues but there was marked expression of COX-2 in ischaemic injured tissues. Comparison of tissues immediately following ischaemia (0 minutes) and after recovery (240 minutes) showed little difference in stain intensity, suggesting rapid upregulation of COX-2 during ischaemia with sustained protein levels during the 240 minute recovery. Indomethacin appeared to slightly decrease expression of COX-2.

Figure 8.

Western blot analysis for cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) protein in ileal mucosa before (0) and after (240) a four hour recovery period. All lanes were loaded with an equal amount of protein. COX-1 protein levels appeared slightly elevated in control tissues following the recovery period (240 minutes) whereas there were no detectable elevations in COX-1 levels in ischaemic injured tissues. Treatment with indomethacin (5×10−6 M) had no apparent affect on COX-1 protein levels. Western blots for COX-2 revealed some evidence of COX-2 protein in control tissues but there was marked expression of COX-2 in ischaemic injured tissues. Comparison of tissues immediately following ischaemia and after the recovery period revealed little difference in stain intensity. Indomethacin appeared to slightly decrease the expression of COX-2. STD, COX-1 (70 kDa) or COX-2 (72 kDa) ovine electrophoresis standard (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). Blots are representative of three separate experiments using tissues from separate animals.

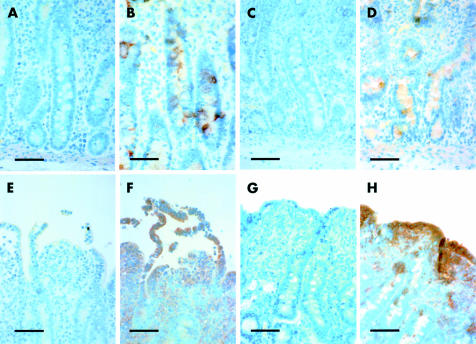

COX immunohistochemistry

To determine the location of the two COX enzymes in this tissue, we performed immunohistochemical analyses immediately after ischaemic injury and following the recovery period. Tissues stained with secondary antibody alone were negative for stain uptake whereas tissues exposed to COX-1 or COX-2 antibody revealed the presence of these proteins in ischaemic injured tissues (fig 9 ▶). COX-1 was noted in intestinal crypt epithelial cells following ischaemic injury (fig 9B ▶) and the recovery period (fig 9D ▶). Staining for COX-2 was noted predominantly in sloughing epithelium following ischaemic injury (fig 9F ▶) and repairing villous epithelium following the recovery period (fig 9H ▶). Staining for COX-2 was also detected in lamina propria mononuclear cells beneath injured or repairing epithelium. There was no apparent effect of indomethacin treatment on COX-1 or COX-2 staining (not shown).

Figure 9.

Immunohistochemical analysis of ischaemic injured tissues before and after a 240 minute recovery period. For purposes of comparison, paired photomicrographs are presented for tissues stained with only the secondary antibody or for tissues also treated with anti-cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) or anti-COX-2. (A) Tissues treated only with secondary antibody showed the presence of only the counterstain whereas tissues additionally treated with anti-COX-1 immediately following ischaemia (B) showed COX-1 protein localised to crypt epithelium. (C, D) Similar results for COX-1 staining were noted after the 240 minute recovery period. (E) Tissues treated only with secondary antibody showed the presence of only the counterstain whereas tissues additionally treated with anti-COX-2 immediately following ischaemia (F) showed COX-2 protein localised to sloughing villous epithelium and lamina propria mononuclear cells. (G, H) Similar results for COX-2 staining were noted after the 240 minute recovery period except that COX-2 was localised to repairing epithelium (1 cm bar=50 μm).

DISCUSSION

Although previous studies have evaluated the importance of COX-2 in mucosal repair9 and the importance of COX-1 and COX-2 in maintenance of mucosal barrier function,26–29 it has been difficult to develop a clear understanding of the relative roles of these enzymes. One reason for this is the inherent complexity of the models used. For example, knockout of one of the COX enzymes may result in compensatory upregulation of activity of the other COX isoform.12 Therefore, it is difficult to apply information from such COX knockout models to wild-type animals that may express both COX enzymes.30 However, not all studies using COX null animals agree on compensatory increases in eicosanoids,26 which compounds the difficulty of interpreting COX knockout studies. On the other hand, in wild-type animals, interpretation of the relative production of eicosanoids such as PGE by the two COX enzymes is hampered by the fact that both COX-1 and COX-2 produce PGE.26 Furthermore, COX-2 is typically upregulated in damaged mucosa in wild-type animals9,31,32 so that its contribution to eicosanoid production may change over time. In the present study, we were able to circumvent these latter difficulties. For example, COX-1 and COX-2 were expressed at stable levels throughout the recovery period commencing immediately following the injurious event. Furthermore, it appears that TXB2 is produced by COX-1 in ischaemic injured porcine mucosa because the selective COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 significantly inhibited TXB2 production whereas the selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 had no effect on TXB2 production unless it was given at very high doses. Such a link between COX enzymes and specific eicosanoid production has been detected in other tissues and may result from a link between specific COX isoforms and TXA2 synthase.33

The results of our study are consistent with the hypothesis that PGE and PGI2 produced by either COX-1 or COX-2 are capable of triggering full recovery of mucosal barrier function. Evidence that elaboration of these eicosanoids by COX-1 can stimulate recovery includes: (1) ischaemic injured tissues treated with the selective COX-2 inhibitor (NS-398) made a full recovery at doses as high as 5×10−5 M; (2) at doses of NS-398 that allowed mucosal recovery, there was no inhibition of TXB2, and continued moderate production of PGE and 6-keto-PGF1α. Evidence that COX-2 elaborated eicosanoids can stimulate recovery includes: (1) treatment with the selective COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 permitted full recovery of barrier resistance despite significant inhibition of TXB2 production; (2) low doses (5×10−8 M) of indomethacin allowed full recovery of barrier resistance in the presence of significant elevations in PGE and 6-keto-PGF1α while continuing to fully inhibit TXB2. However, these data indicate that some degree of inhibition of prostanoids can be tolerated without affecting recovery. We believe that our data can best be explained by an apparent minimal concentration of prostanoids, particularly PGE, which can stimulate recovery. For example, 10−8 M indomethacin allows full recovery (fig 4 ▶) in the presence of 120 (15) pg/ml PGE (fig 5 ▶) whereas higher doses of indomethacin with corresponding lower concentrations of PGE (<20 pg/ml) do not allow recovery. Similarly, 10−4 M NS-398 inhibits full recovery (fig 6 ▶) in the presence of 55 (14) pg/ml PGE whereas lower doses of NS-398 with corresponding higher concentrations of PGE (>110 pg/ml) allow full recovery. Thus we propose that a minimal concentration of ∼110 pg/ml PGE by 240 minutes is required for full recovery in this model.

Some additional findings related to eicosanoid production (fig 3 ▶) suggest that COX-1 is responsible for a greater proportion of prostanoid elaboration during the early phase of mucosal recovery whereas COX-2 may be responsible for greater prostanoid production during the latter period of mucosal recovery. For example, PGE, 6-keto-PGF1α, and TXB2 were all significantly inhibited by SC-560 and indomethacin at the 60 minute time period but not by NS-398. On the other hand, PGE and 6-keto-PGF1α were significantly inhibited by NS-398 and indomethacin at the 240 minute time period but not by SC-560. However, data on SC-560 suggest that at 5×10−6 M, this agent was not fully inhibiting COX-1. Thus although TXB2 was significantly inhibited by SC-560, it was not fully inhibited. It is therefore possible that at a dose of SC-560 that was high enough to fully inhibit TXB2, significant inhibition of PGE and 6-keto-PGF1α would be detected that should correspond to that fraction of these prostanoids that were not inhibited by NS-398.

A recent study has shown that both COX-1 and COX-2 contribute to homeostasis of the mucosal barrier. For example, COX-1 or COX-2 null mice demonstrated increased colonic mucosal ulceration in response to dextran sodium sulphate compared with wild-type controls.26 Furthermore, there was an additive increase in susceptibility to dextran sodium sulphate induced mucosal injury in COX-1 null mice treated with NS-398.26 Whether such changes in mucosal ulceration resulted from changes in mucosal susceptibility to dextran sodium sulphate induced injury or differences in the rate of mucosal recovery was not clear. Studies on recovery of pre-existent injury in wild-type animals do not provide firm conclusions on the role of COX isoforms. For example, NS-398 retarded gastric ulcer repair in mice,9 and exacerbated colonic inflammation in rats,34 but these findings were not compared with the effects of a relatively non-selective COX inhibitor such as indomethacin or with a selective COX-1 inhibitor. In studies where comparisons between selective COX-2 inhibitors and non-selective COX inhibitors were performed, both classes of drugs were shown to inhibit repair of gastric ulcers to a similar extent,27–29 suggesting that COX-2 rather than COX-1 eicosanoids are required for recovery of ulcerated gastric mucosa. However, the relative roles of COX-1 and COX-2 could not be distinguished because there were no experiments in which COX-1 was selectively inhibited. We approached this problem by comparing the effects of selective inhibitors of COX-1 or COX-2 with that of the non-selective COX inhibitor indomethacin. In so doing, we came to the conclusion that both COX-1 and COX-2 play a role in mucosal reparative events in ischaemic injured small intestine.

The finding that indomethacin showed evidence of COX-1 selectivity at low doses was not entirely unexpected as many of the so-called non-selective COX inhibitors show some degree of specificity for COX-1. In particular, indomethacin and aspirin show a relatively high degree of specificity for COX-1 compared with agents such as ibuprofen, which essentially inhibits both COX enzymes to the same degree.35,36 None the less, indomethacin appears to be a potent COX inhibitor as at doses as low as 5×10−7 M, indomethacin inhibited all eicosanoid production. However, some degree of selectivity for COX-1 became evident at a dose of 5×10−8 M.

The mechanism by which COX elaborated eicosanoids stimulate recovery of ischaemic injured porcine epithelium remains to be fully elucidated but it appears to involve closure of dilated paracellular spaces rather than an effect on epithelial restitution.6,37,38 Such a mechanism would explain the lack of differences among the various treatments when evaluating histological indices of restitution in the present study (fig 2 ▶). In fact, in previous studies, we have shown that epithelial restitution in this model is near complete within 60 minutes38 at a time when there is little evidence of recovery of transepithelial resistance. Recovery of resistance is subsequently associated with closure of inter-epithelial spaces within restituted epithelium.37,38 Thus restitution is likely a critical initial step in the repair process prior to recovery of paracellular resistance. The rapidity of restitution shown in our model is similar to other ex vivo model systems. For example, in guinea pig ileum, treatment with detergent (Triton-X 100) resulted in sloughing of epithelium from the tips of villi that was able to restitute within 60 minutes following detergent washout.39,40 The rate of epithelial restitution in ex vivo model systems may be more rapid than in in vitro models of restitution41 because of the absence of concurrent reparative mechanisms in vitro. For example, villous contraction in ex vivo models dramatically reduces the denuded surface area that remains to be restituted such that far fewer cells are required to reseal a defect.39 We have previously documented significant decreases in villous height during recovery of ischaemic injured porcine ileum as evidence of this mechanism.6

The fact that either COX-1 or COX-2 elaborated eicosanoids appeared equally capable of stimulating mucosal recovery is somewhat puzzling given the immunohistochemical localisation of these enzymes. COX-2 was expressed within repairing epithelium and adjacent mononuclear cells but COX-1 was localised to crypt epithelium, which raises the question as to how prostanoids released by crypt epithelium might stimulate recovery of injured villous epithelium. We are confident of our immunohistochemical results because COX-1 has been localised to crypt epithelium in the mouse,42 and humans,31 and COX-2 has been localised to repairing epithelium and subepithelial mononuclear cells in patients with Crohn's disease.31 One possible integrative signalling mechanism whereby prostanoids released by crypt epithelium might stimulate recovery of villous epithelium is the enteric nervous system, particularly as it is now well established that certain prostaglandins, notably PGE2 and PGI2, are powerful neuromodulators.43 However, a full understanding of such mechanisms will require further study.

Clinical Evidence—Call for contributors.

Clinical Evidence is a regularly updated evidence based journal available world wide both as a paper version and on the internet. Clinical Evidence urgently needs to recruit a number of new contributors. Contributors are health care professionals or epidemiologists with experience in evidence based medicine and the ability to write in a concise and structured way.

We are presently interested in finding contributors with an interest in the following clinical areas:

Acute bronchitis

Acute sinusitis

Cataract

Genital warts

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis C

HIV

Being a contributor involves:

Appraising the results of literature searches (performed by our Information Specialists) to identify high quality evidence for inclusion in the journal.

Writing to a highly structured template (about 1500–3000 words), using evidence from selected studies, within 6–8 weeks of receiving the literature search results.

Working with Clinical Evidence Editors to ensure that the text meets rigorous epidemiological and style standards.

Updating the text every eight months to incorporate new evidence.

Expanding the topic to include new questions once every 12–18 months.

If you would like to become a contributor for Clinical Evidence or require more information about what this involves please send your contact details and a copy of your CV, clearly stating the clinical area you are interested in, to Polly Brown (pbrown@bmjgroup.com).

Acknowledgments

NIH grant DK53284 (ATB) and USDA grant 9802537 (ATB). We thank the Immunotechnology Core of the Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease (NIH Center Grant DK34987) for assistance with the eicosanoid assays.

Abbreviations

COX, cyclooxygenase

Isc, short circuit current

Jms, mucosal to serosal flux

NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

PGE, prostaglandins E1 and E2

PGI2, prostaglandin I2

R, transepithelial electrical resistance

PD, potential difference

TXB2, thromboxane B2

SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

PBS, phosphate buffered saline

REFERENCES

- 1.Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat New Biol 1971;231:232–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace JL. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastroenteropathy: the second hundred years. Gastroenterology 1997;112:1000–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robert A. Cytoprotection by prostaglandins in rats. Prevention of gastric necrosis produced by alcohol, HCl, NaOH, hypertonic NaCl, and thermal injury. Gastroenterology 1979;77:433–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert A. Cytoprotection by prostaglandins. Gastroenterology 1979;77:761–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller TA. Protective effects of prostaglandins against gastric mucosal damage: current knowledge and proposed mechanisms. Am J Physiol 1983;245:G601–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blikslager AT, Roberts MC, Rhoads JM, et al. Prostaglandins I2 and E2 have a synergistic role in rescuing epithelial barrier function in porcine ileum. J Clin Invest 1997;100:1928–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zushi S. Role of prostaglandins in intestinal epithelial restitution stimulated by growth factors. Am J Physiol 1996;270:G757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erickson RA. 16,16-Dimethyl prostaglandin E2 induces villus contraction in rats without affecting intestinal restitution. Gastroenterology 1990;99:708–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuno H. Induction of cyclooxygenase 2 in gastric mucosal lesions and its inhibition by the specific antagonist delays healing in mice. Gastroenterology 1997;112:387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vane JR. Inducible isoforms of cyclooxygenase and nitric-oxide synthase in inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:2046–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kargman S. Characterization of prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 and 2 in rat, dog, monkey, and human gastrointestinal tracts. Gastroenterology 1996;111:445–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirtikara K, Morham SG, Raghow R, et al. Compensatory prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis in cyclooxygenase 1 or 2 null cells. J Exp Med 1998;187:517–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langenbach R, Morham SG, Tiano HF, et al. Prostaglandin synthase 1 gene disruption in mice reduces arachidonic acid-induced inflammation and indomethacin-induced gastric ulceration. Cell 1995;83:483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stenson WF. Cyclooxygenase 2 and wound healing in the stomach. Gastroenterology 1997;112:645–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masferrer JL, Zweifel BS, Manning PT, et al. Selective inhibition of inducible cyclooxygenase 2 in vivo is antiinflammatory and nonulcerogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:3228–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahbazian A, Schuligoi R, Heinemann A, et al. Disturbance of peristalsis in the guinea-pig isolated small intestine by indomethacin, but not cyclo-oxygenase isoform-selective inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol 2001;132:1299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacNaughton WK, Cushing K. Role of constitutive cyclooxygenase-2 in prostaglandin-dependent secretion in mouse colon in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000;293:539–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Argenzio RA, Lecce J, Powell DW. Prostanoids inhibit intestinal NaCl absorption in experimental porcine cryptosporidiosis. Gastroenterology 1993;104:440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argenzio RA, Liacos JA, Levy ML, et al. Villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, cellular infiltration, and impaired glucose-Na absorption in enteric cryptosporidiosis of pigs. Gastroenterology 1990;98:1129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Argenzio RA, Liacos JA. Endogenous prostanoids control ion transport across neonatal porcine ileum in vitro. Am J Vet Res 1990;51:747–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madara JL. Effects of cytochalasin D on occluding junctions of intestinal absorptive cells: further evidence that the cytoskeleton may influence paracellular permeability and junctional charge selectivity. J Cell Biol 1986;102:2125–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madara JL. Interferon-gamma directly affects barrier function of cultured intestinal epithelial monolayers. J Clin Invest 1989;83:724–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrignani P, Sciulli MG, Manarini S, et al. COX-2 is not involved in thromboxane biosynthesis by activated human platelets. J Physiol Pharmacol 1999;50:661–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAdam BF, Catella-Lawson F, Mardini IA, et al. Systemic biosynthesis of prostacyclin by cyclooxygenase (COX)-2: the human pharmacology of a selective inhibitor of COX-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:272–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cullen L, Kelly L, Connor SO, et al. Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition by nimesulide in man. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998;287:578–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morteau O, Morham SG, Sellon R, et al. Impaired mucosal defense to acute colonic injury in mice lacking cyclooxygenase-1 or cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest 2000;105:469–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeuchi K, Suzuki K, Yamamoto H, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective and nitric oxide-releasing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastric mucosal responses. J Physiol Pharmacol 1998;49:501–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ukawa H, Yamakuni H, Kato S, et al. Effects of cyclooxygenase-2 selective and nitric oxide-releasing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on mucosal ulcerogenic and healing responses of the stomach. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:2003–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmassmann A. Mechanisms of ulcer healing and effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med 1998;104:43–51S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawkey CJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Gastroenterology 2000;119:521–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer II, Kawka DW, Schloemann S, et al. Cyclooxygenase 2 is induced in colonic epithelial cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1998;115:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendel J, Nielsen OH. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in active inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:1170–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penglis PS, Cleland LG, Demasi M, et al. Differential regulation of prostaglandin E2 and thromboxane A2 production in human monocytes: implications for the use of cyclooxygenase inhibitors. J Immunol 2000;165:1605–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reuter BK. Exacerbation of inflammation-associated colonic injury in rat through inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest 1996;98:2076–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meade EA, Smith WL, DeWitt DL. Differential inhibition of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase (cyclooxygenase) isozymes by aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Biol Chem 1993;268:6610–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glaser K, Sung ML, O'Neill K, et al. Etodolac selectively inhibits human prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 (PGHS-2) versus human PGHS-1. Eur J Pharmacol 1995;281:107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blikslager AT, Roberts MC, Argenzio RA. Prostaglandin-induced recovery of barrier function in porcine ileum is triggered by chloride secretion. Am J Physiol 1999;276:G28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blikslager AT, Roberts MC, Young KM, et al. Genistein augments prostaglandin-induced recovery of barrier function in ischemia-injured porcine ileum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;278:G207–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore R, Carlson S, Madara JL. Villus contraction aids repair of intestinal epithelium after injury. Am J Physiol 1989;257:G274–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore R, Carlson S, Madara JL. Rapid barrier restitution in an in vitro model of intestinal epithelial injury. Lab Invest 1989;60:237–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nusrat A, Delp C, Madara JL. Intestinal epithelial restitution. Characterization of a cell culture model and mapping of cytoskeletal elements in migrating cells. J Clin Invest 1992;89:1501–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iseki S. Immunocytochemical localization of cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 in the rat stomach. Histochem J 1995;27:323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell DW. Immunophysiology of intestinal electrolyte transport. In: Handbook of physiology, vol IV. Intestinal absorption and secretion. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society, 1991:591–641.