Abstract

There is an increased risk of small bowel adenocarcinoma in patients with coeliac disease compared with the normal population. It has been suggested that adenocarcinoma of the small intestine in coeliac disease arises through an adenoma-carcinoma sequence but there has been only one reported case of a small bowel adenoma in a patient with coeliac disease. We report three additional cases of a small bowel adenoma in the setting of coeliac disease. In addition, four cases of small bowel adenocarcinoma are also reported, one of which was found adjacent to a jejunal villous adenoma. These cases emphasise the risk of the development of small bowel neoplasia for patients with coeliac disease and support the concept that small bowel adenocarcinoma in coeliac disease arises from adenomas.

Keywords: adenocarcinoma, adenoma, coeliac disease, neoplasia, small bowel

Small intestinal adenocarcinomas are extremely uncommon in the general population, with the average annual age adjusted incidence estimated to be 3.7 per million persons.1 In comparison, coeliac disease is associated with a markedly increased risk of development of small intestinal adenocarcinoma (relative risk 60–80-fold).2,3 A recent large population based study of malignancy in patients with coeliac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis from Sweden confirmed the increased risk for small intestinal cancer, although the risk was less than previous studies (10-fold).4

Similar to the situation in the large bowel, there is evidence that small bowel adenocarcinomas also arise from pre-existing adenomas.5,6 Although there have been many reported cases of small bowel adenocarcinoma developing in coeliac disease patients,7–15 there has been only one published case of a small bowel adenoma in a patient with coeliac disease.16 Within our cohort of patients with coeliac disease, we have encountered three patients with a small bowel adenoma and four with adenocarcinoma of the small bowel. In one of the patients, an adenocarcinoma clearly developed within a villous adenoma, lending support to the adenoma-carcinoma theory for small bowel adenocarcinoma in coeliac disease.

CASE SERIES

Seven patients were identified from 417 with coeliac disease seen in our Coeliac Disease Centre over a 20 year period between 1981 and 2000. All neoplasms were diagnosed after 1995. There were five males and two females. Mean age of the patients at diagnosis of the neoplasm was 53 years (range 21–83).

Patients with small bowel adenoma

Three patients (two males and one female) with adenomas were a mean age of 63 years (range 53–83) at diagnosis of the adenoma (table 1 ▶). The diagnosis of coeliac disease, based on clinical and histological improvement on a gluten free diet, was established a mean of 27 years earlier (range 4–39). Each patient had adhered to a gluten free diet and denied gastrointestinal symptoms. All serological studies were negative at the time of the diagnosis of the adenoma. Adenomas were identified in the descending duodenum, remote from the ampulla during oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) performed to assess the status of coeliac disease. The histological appearance of the non-adenomatous duodenal mucosa revealed partial villous atrophy consistent with treated coeliac disease.17 Colonoscopy failed to reveal adenomatous polyps in all patients. One patient is described in detail (case No 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and clinical presentation of patients with adenoma and carcinoma of the small intestine in the coeliac disease patient population

| Case No | Sex | Age of CD Dx (y) | Age of neoplasia Dx (y) | Type of neoplasia | Location | Presentation | Diagnostic study |

| 1 | M | 49 | 53 | Adenoma | Duodenum | Asymptomatic | OGD* |

| 2 | F | 44 | 83 | Adenoma | Duodenum | Asymptomatic | OGD* |

| 3 | M | 16 | 53 | Adenoma | Duodenum | Asymptomatic | OGD* |

| 4 | M | 31† | 21 | Adenocarcinoma | Ileum | Acute abdomen | Exploratory laparotomy |

| 5 | M | Infant †‡ | 55 | Adenocarcinoma | Jejunum | Acute abdomen | Exploratory laparotomy |

| 6 | F | 70 | 70 | Adenocarcinoma | Jejunum | Iron deficiency anaemia | Abdominal CT enteroscopy |

| 7 | M | Infant ‡ | 55 | Adenoma; adenocarcinoma | Jejunum | Iron deficiency anaemia | UGI/SI enteroscopy |

CD, coeliac disease; Dx, diagnosis; UGI/SI, upper gastrointestinal series with small intestinal series; OGD, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy; CT, computed tomography.

*OGD performed to check the status of coeliac disease.

†Coeliac disease diagnosed after pathology slides from small bowel adenocarcinoma resection were reviewed.

‡Originally diagnosed in infancy but were told they “grew out of it.” Therefore, had been exposed to gluten >50 years; subsequently re-diagnosed with coeliac disease as adults.

Case No 1

The patient, a 53 year old White male, presented for reassessment of coeliac disease which had been diagnosed four years earlier during evaluation for iron deficiency anaemia. At that time colonoscopy was negative. OGD was normal apart from changes in the duodenum consistent with coeliac disease. A duodenal biopsy revealed total villous atrophy. Coeliac serologies including antigliadin IgA, antigliadin IgG, and antiendomysial antibody were positive. The patient was started on a gluten free diet and has since been compliant for the past four years.

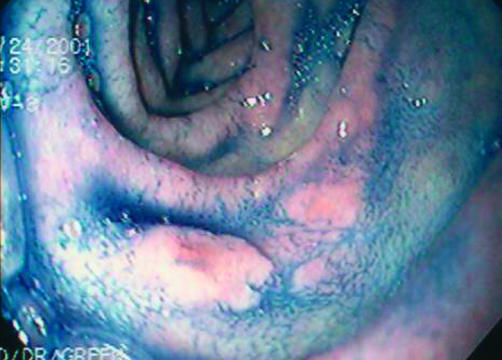

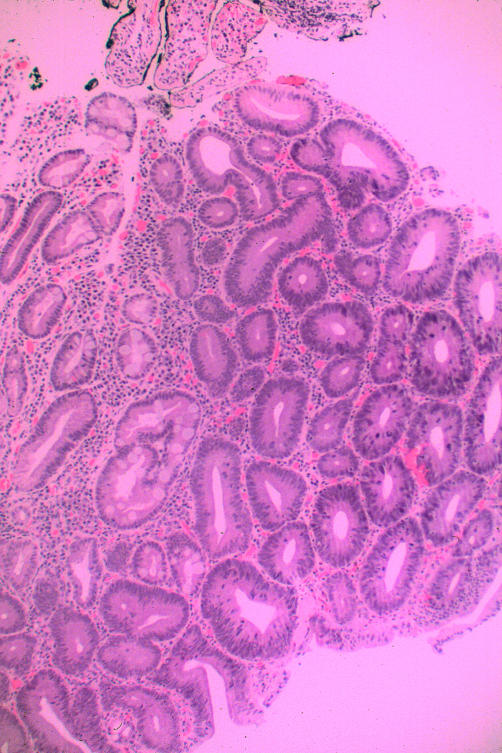

He was asymptomatic when seen by us. Physical examination was normal, as were laboratory results, including complete blood count and serum ferritin. Coeliac serologies were negative. OGD, performed to reassess the status of his coeliac disease, was remarkable for scalloping and fissuring of the duodenal mucosa. In addition, there was a poorly defined area of nodularity in the descending duodenum, biopsy of which revealed an adenomatous tissue. The patient was re-endoscoped with the intention of removing the entire adenoma. The borders of the duodenal lesion were demarcated using indigo carmine (fig 1 ▶). The lesion was then removed using a saline assisted technique. Histological examination of the polyp revealed a tubular adenoma with dysplastic changes (fig 2 ▶). A subsequent enteroscopy did not reveal any other neoplastic lesions.

Figure 1.

Chromoendoscopy (indigo carmine 0.08%) defining the borders of the sessile polyp in the descending duodenum.

Figure 2.

Biopsy of a duodenal polyp. The bottom portion of the picture shows a normal glandular architecture with well formed goblet cells. The middle portion begins to show adenomatous changes. The top portion shows dysplasia with crowding and pleomorphism of nuclei, nuclear stratification with nuclei found apically, and prominent nucleoli. Haematoxylin and eosin, ×80.

Patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma

In four patients with adenocarcinoma (table 2 ▶), carcinoma was diagnosed at a mean age of 50 years (range 21–70). There were three males and one female. Presentations were that of an acute abdomen in two patients. One, a 21 year old male, was considered to have an acute appendicitis but a perforated ileal carcinoma was identified at laparotomy. The other, a 55 year old male, presented with small intestinal obstruction due to intussusception of a jejunal mass. In both of these cases the original pathological interpretation failed to identify changes of coeliac disease in adjacent mucosa, remote from the carcinoma. The changes due to coeliac disease, severe villous atrophy and intraepithelial lymphocytosis, were recognised when the original slides were reviewed. The 55 year old male knew of a childhood diagnosis of coeliac disease but because he had been told that he had grown out of the disease he had consumed a regular diet from age five years. This patient was commenced on a gluten free diet. He has remained well. When initially seen by us, he had been on a gluten free diet for 12 months. Coeliac serologies were negative; OGD and enteroscopy revealed mucosal fissures and scalloping of folds. Biopsies revealed partial villous atrophy. Colonoscopy was normal without polyps.

Table 2.

Pathological features of small intestine adenocarcinoma in the coeliac disease patient population

| Case No | Depth of penetration | Nodal involvement | Distant metastasis | Histological features | Histological findings consistent with CD |

| 4 | Through serosa | Positive | None | Well differentiated | Subtotal villous atrophy |

| 5 | Through serosa | Negative | None | Poorly differentiated; signet ring | Partial villous atrophy |

| 6 | Through serosa | Negative | None | Moderate-poor differentiation; | Partial villous atrophy |

| 7 | Through serosa | Positive | None | Moderate differentiation; mucinous; villous adenoma with severe atypia | Subtotal villous atrophy |

The other two patients presented with iron deficiency anaemia. Radiological studies revealed a jejunal mass in both patients. Coeliac disease was diagnosed at the time of enteroscopy that was performed to biopsy the jejunal mass. Diagnosis was based on the presence of subtotal villous atrophy identified in biopsies taken from the duodenum in both patients. Both patients had positive antigliadin antibodies. Endomysial antibodies were not performed. Colonoscopy was negative.

All adenocarcinomas presented at an advanced stage with invasion through the serosa. No other adenomas were identified in the upper or lower gastrointestinal tract. Only one patient had identifiable adenomatous tissue adjacent to the cancer. None had evidence of flat dysplasia adjacent to the tumour. Regional lymph nodes were involved in two of the patients. None however had distant metastases. Three of the patients (case Nos 4, 5, and 7) had improvement of duodenal histology while on a gluten free diet. The fourth has not undergone repeat biopsy. One case is presented in detail (case No 7).

Case No 7

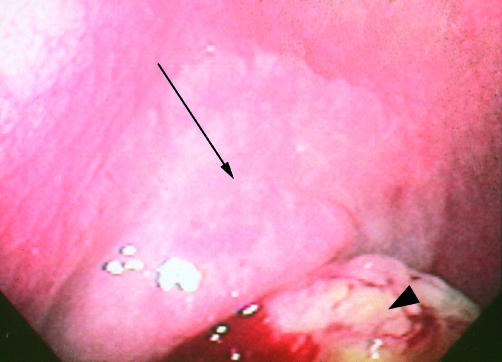

A 55 year old male presented with fatigue due to iron deficiency anaemia. While colonoscopy was normal, an upper gastrointestinal series revealed a jejunal mass. The patient was referred for enteroscopy, which revealed reduced folds, scalloping of folds, and mucosal fissures in the duodenum and jejunum. In addition, a mass was identified in the jejunum (fig 3 ▶). Adjacent to the mass was a pale plaque-like area which was also biopsied. Over the subsequent days the patient learned from his mother that he had a diagnosis of coeliac disease in infancy but because she had later been told he had grown out of the disease she permitted him to consume a normal diet from early childhood. Anti-IgA gliadin and anti-IgG gliadin were positive. Histological evaluation revealed a mucinous adenocarcinoma of the jejunum with an adjacent villous adenoma. Biopsy of the duodenum revealed subtotal villous atrophy. The patient underwent resection of the mass. Invasion through the serosa and positive lymph nodes were identified in the resected specimen. He subsequently underwent chemotherapy for one year with 5-fluorouracil/leukovorin/levamisole. Re-exploration was performed six years later for evidence of recurrent disease identified on abdominal computed tomography scanning. He was found to have complete obstruction at the ligament of Treitz secondary to a retroperitoneal mass. He underwent further jejunal resection and bypass of the mass. He remains on a gluten free diet.

Figure 3.

Arrow indicates jejunal mass seen during enteroscopy. Histological evaluation revealed a mucinous adenocarcinoma. Biopsy of a pale plaque-like area adjacent to the mass (arrowhead) revealed villous adenoma.

DISCUSSION

Tumours of the small bowel represent only 1–5% of all gastrointestinal malignancies, which is striking as the small intestine accounts for 75% of the length and 90% of the mucosal surface area of the gastrointestinal tract.18,19 Small intestinal malignancies are rare in the general population. However, there are several precursor states for small intestinal adenocarcinoma which include familial polyposis syndromes, coeliac disease, and Crohn’s disease.20

Although the association between coeliac disease and small bowel adenocarcinoma is well established, it is based on only a small number of patients and most of the existing literature is in the form of case reports.7,8,13–15 In a large collaborative study conducted by Swinson et al in the UK,3 235 coeliac patients were found to have 259 malignancies. Nineteen of these neoplasms were small bowel adenocarcinomas compared with an expected incidence of 0.23 cases. The relative risk for small bowel adenocarcinoma was 82.6, which was equivalent to the risk of colon cancer in the general population. This study, conducted in the late 1970s, may have overestimated the risk of small bowel malignancy in coeliac disease as a significant percentage of the patient population may have been non-compliant with the gluten free diet. Similarly, in a series of patients with coeliac disease from the USA, an increased risk of adenocarcinoma of the small bowel was identified.2 This study however was conducted as a national survey and its estimated risk was based on two patients who had small bowel adenocarcinoma. The risk of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine was more modestly increased (10-fold) in a large population based study of patients with coeliac disease in Sweden.4

Small bowel adenocarcinomas are similar to large bowel adenocarcinomas in that they are considered to arise from a preexisting adenoma.6 Unlike Crohn’s disease in which there is evidence for a dysplasia-carcinoma sequence,21 coeliac disease shows no evidence of a premalignant field defect or flat dysplasia in mucosa adjacent to carcinoma.22 Thus an adenoma-carcinoma sequence is considered the most likely mode of development of adenocarcinoma, despite only one published case of a small bowel adenoma in a patient with coeliac disease.16 Our cases lend support to the adenoma-carcinoma theory. Typically, small bowel adenocarcinomas present at an advanced stage23 and, as a result, a pre-existing adenoma would usually be completely replaced by invasive carcinoma.

Our cases reveal important factors about small intestinal carcinomas in coeliac disease. Firstly, while coeliac disease is a female predominant disease,24 most of the reported cases of small intestinal adenocarcinoma have been in men.8 However, the increased risk for this cancer occurs in both men and women, although it is greater for men.4 Secondly, the risk of carcinoma appears to be greatest in patients with longstanding coeliac disease.8 In our series, two 55 year old men had a diagnosis of coeliac disease in childhood, apparently responded to a gluten free diet, and were considered to have “grown out of the disease,” only to be diagnosed later in life. Unfortunately, their presentation and re-diagnosis of coeliac disease was due to a malignant complication of the disease. Loss of symptoms is not unusual in patients with coeliac disease during adolescence.25 This may be mistaken for resolution of the disease. These cases emphasise the life long nature of coeliac disease.

Previous case reports have described patients in whom the diagnosis of coeliac disease was not made until the time of resection for small bowel adenocarcinoma. In these patients, histological examination of the specimen showed villous atrophy in adjacent non-neoplastic mucosa.9,11,12,14 Moreover, there have been cases in which there was further delay in the diagnosis of coeliac disease when villous atrophy was initially missed during pathological evaluation of the resected specimen but was later found after the original specimen was reviewed.12 Two of our cases were diagnosed in a similar fashion, after review of the original pathological materials.

One of our patients presented at age 21 years with an adenocarcinoma of the ileum. Malignancy in childhood coeliac disease is unusual although it may be under reported.26 The large Swedish study however demonstrated that the greatest risk for adenocarcinoma is in the age group 20–59 years.4 Our patient had no other risk factor for small bowel adenocarcinoma.20

Most of the literature concerning series of patients with adenocarcinoma and coeliac disease were published in the 1970s and 1980s, in patients with longstanding malabsorption. In comparison, our patients were all diagnosed with carcinoma due to coeliac disease in the late 1990s. This indicates that although coeliac disease is considered to be a rare disease in the USA, the development of small intestine adenocarcinoma in patients with coeliac disease is an active problem. Coeliac disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis when clinicians and pathologists encounter patients presenting with small intestinal adenomas and carcinomas.

Currently, there are no established guidelines concerning the role of surveying patients with longstanding coeliac disease.27 Our finding that patients with coeliac disease develop duodenal adenomas raises the possibility that OGD may serve as a means of surveillance for neoplasia in patients with coeliac disease. However, the role of other modalities that evaluate the small intestine need to be explored because, in coeliac disease, the majority of cancers occur more distally in the intestine.8

In conclusion, our patients with coeliac disease and small intestinal adenomas and carcinomas support an adenoma-carcinoma sequence for the development of cancer of the small intestine in coeliac disease. In addition, they underscore the premalignant nature of the disease.

Abbreviations

OGD, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy

REFERENCES

- 1.Chow JS, Chen CC, Ahsan H, et al. A population-based study of the incidence of malignant small bowel tumours: SEER, 1973–1990. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:722–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green PHR, Stavropoulos SN, Panagi SG, et al. Characteristics of adult celiac disease in the USA: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swinson CM, Slavin G, Coles EC, et al. Coeliac disease and malignancy. Lancet 1983;1:111–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Askling J, Linet M, Gridley G, et al. Cancer incidence in a population-based cohort of individuals hospitalized with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1428–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perzin KH, Bridge MF. Adenomas of the small intestine: a clinicopathologic review of 51 cases and a study of their relationship to carcinoma. Cancer 1981;48:799–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sellner F. Investigations on the significance of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the small bowel. Cancer 1990;66:702–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenwright S. Coeliac disease and small bowel carcinoma. Postgrad Med J 1972;48:673–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes GK, Dunn GI, Cockel R, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the upper small bowel complicating coeliac disease. Gut 1980;21:1010–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen SN, Wold LE. Adenocarcinoma of jejunum in association with nontropical sprue. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1986;110:822–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straker RJ, Gunasekaran S, Brady PG. Adenocarcinoma of the jejunum in association with celiac sprue. J Clin Gastroenterol 1989;11:320–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsch SC, Heer M, Sulser H, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine in celiac disease. (Case report and literature review). Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1990;120:135–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacGowan DJ, Hourihane DO, Tanner WA, et al. Duodeno-jejunal adenocarcinoma as a first presentation of coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol 1996;49:602–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javier J, Lukie B. Duodenal adenocarcinoma complicating celiac sprue. Dig Dis Sci 1980;25:150–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrell DJ, Shrimankar J, Griffin SM. Duodenal adenocarcinoma complicating coeliac disease. Histopathology 1991;19:285–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selby WS, Gallagher ND. Malignancy in a 19-year experience of adult celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci 1979;24:684–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishman MJ, Jeejeebhoy KN, Gopinath N, et al. Small intestinal villous adenoma and celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:748–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahab PJ, Meijer JW, Mulder CJ. Histologic follow-up of people with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet: Slow and incomplete recovery. Am J Clin Pathol 2002;118:459–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arber N, Neugut AI, Weinstein IB, et al. Molecular genetics of small bowel cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997;6:745–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neugut AI, Jacobson JS, Suh S, et al. The epidemiology of cancer of the small bowel. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1998;7:243–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green PHR, Jabri, B. Celiac disease and other precursors to small intestinal malignancy. Gastroenterol Clin of North Am 2002;31:625–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson S, Traube J, Riddell RH. The histologic appearance of dysplasia (precarcinomatous change) in Crohn’s disease of the small and large intestine. Gastroenterology 1981;81:492–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruno CJ, Batts KP, Ahlquist DA. Evidence against flat dysplasia as a regional field defect in small bowel adenocarcinoma associated with celiac sprue. Mayo Clin Proc 1997;72:320–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aghazarian SG, Birely BC. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine: a plea for early diagnosis. South Med J 1993;86:1067–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Celiac sprue. N Engl J Med 2002;346:180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar PJ, Walker-Smith J, Milla P, et al. The teenage coeliac: follow up study of 102 patients. Arch Dis Child 1988;63:916–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schweizer JJ, Oren A, Mearin ML. Cancer in children with celiac disease: A survey of the European society of paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;33:97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Celiac Sprue. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1522–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]