Abstract

Background: Dyspepsia is a chronic disease with significant impact on the use of health care resources. A management strategy based on Helicobacter pylori testing has been recommended but the long term effect is unknown.

Aim: To investigate the long term effect of a test and treat strategy compared with prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients in primary care.

Patients: A total of 500 patients presenting in primary care with dyspepsia were randomised to management by H pylori testing plus eradication therapy (n = 250) or by endoscopy (n = 250). Results of 12 month follow up have previously been presented.

Methods: Symptoms, quality of life, and patient satisfaction were recorded during a three month period, a median 6.7 years after randomisation (range 6.1–7.3 years). Number of endoscopies, antisecretory medication, H pylori treatments, and hospital visits were recorded from health care databases for the entire follow up period.

Results: Median age was 45 years; 28% were H pylori infected. Use of resources was registered in all 500 patients (3084 person years) of whom 312 completed diaries. We found no difference in symptoms between the two groups. Median proportion of days without symptoms was 0.52 (interquartile range 0.10–0.88) in the test and eradicate group versus 0.64 (0.14–0.90) in the prompt endoscopy group (p = 0.27) (mean difference 0.05 (95% confidence interval (CI) −0.03 to 0.14)). Compared with the prompt endoscopy group, the test and eradicate group underwent fewer endoscopies (mean difference 0.62 endoscopies/person (95% CI 0.38–0.86)) and used less antisecretory medication (mean difference 102 defined daily doses/person (95% CI −1 to 205)).

Conclusion: On a long term basis, a H pylori test and eradicate strategy is as efficient as prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients in primary care and reduces the use of endoscopy and antisecretory medication.

Keywords: dyspepsia, endoscopy, Helicobacter pylori, randomised controlled trial

Normally, dyspepsia is a chronic relapsing condition with significant impact on the use of health care resources.1,2 The main findings in dyspepsia are functional dyspepsia (>50%), peptic ulcer disease (20%), gastro-oesophageal reflux (20–30%), and gastric carcinoma (<2%).2

Infection with Helicobacter pylori is the main risk factor for peptic ulcer disease. As peptic ulcers are cured after successful H pylori eradication, a test and eradicate strategy based on screening for and treatment of H pylori has been recommended for management of young dyspeptic patients in primary care.2,3 Alternative management strategies are based on empiric antisecretory medication and/or prompt endoscopy. None of these strategies has ousted the others, and the most cost effective approach to the initial assessment and management of dyspepsia is controversial.1 Simulation models4–7 and randomised trials1,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 have compared the strategies with a one year perspective, but long term consequences are unknown.

The aim of this study was to investigate the long term effectiveness of a test and treat strategy compared with prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients in primary care

METHODS

Details of the intervention and the results of a 12 month follow up have been described previously.17

All patients who consulted their general practitioner with dyspepsia of at least two weeks’ duration and of a nature and severity that caused the physician to suggest treatment or investigation of any kind were eligible for the trial. Dyspepsia was defined as epigastric pain or discomfort with or without heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, or bloating.

The following exclusion criteria were used: age younger than 18 years; treatment with H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors within the preceding month; unintended weight loss of more than 3 kg; suspicion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, anaemia, or jaundice; unable to give informed consent; and unfit for endoscopy. All patients gave informed consent before inclusion, and the local ethics committee approved the trial.

Patients were identified in primary care and referred directly to the study. All patients were interviewed and individually randomised and investigated within two weeks of referral. Inclusion, interviews, and investigations were performed by the study investigator (ATL).

Randomisation was done in blocks of 10 with tables of random numbers, and the results were kept in sealed numbered envelopes.

Patients were randomised to H pylori test and eradicate or to prompt endoscopy. Patients assigned to H pylori testing were investigated by 13C-urea breath test. Infected patients received a two week H pylori eradication treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), amoxicillin, and metronidazole. H pylori negative patients who had taken any amount of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (including aspirin) during the previous month were investigated by endoscopy. H pylori negative patients with reflux symptoms and not using NSAIDs were treated with a PPI. H pylori negative patients not using NSAIDs and without reflux symptoms were managed by reassurance.

Patients assigned to prompt endoscopy were treated in accordance with endoscopic findings. All gastric ulcer patients infected by H pylori and all duodenal ulcer patients had H pylori eradication treatment followed by PPI treatment for 2–4 weeks. H pylori negative gastric ulcer patients and patients with oesophagitis were treated with a PPI. Patients with normal findings were diagnosed as having functional dyspepsia and were managed by reassurance.

At the end of one year of follow up, patients assigned to endoscopy were informed about the results of blinded H pylori tests performed at entry to the study in all patients.

Patients were enrolled in 1995–1996 and initially followed for 12 months, with registration of dyspeptic symptoms in diaries for one week per month and with interview at entry, after one month, and after one year.17

After 12 months of follow up, patients had no further contact with the study and all treatments and investigations were carried out by the general practitioner

Long term assessment was carried out in autumn 2002. Patients were contacted by letter and asked to register symptoms in diaries for one week per month over a three month period. Dyspeptic symptoms were graded daily (no, mild, moderate, or severe influence on lifestyle of any dyspeptic symptom) and sick leave days and visits to a general practitioner in the previous month were also registered.

Patients completed a questionnaire at the beginning and end of the three month follow up. The questionnaire measured symptoms, patient satisfaction, and quality of life by validated scales: gastrointestinal symptom rating scale,18 satisfaction with dyspepsia related health,19 and psychological general well being index.20 Furthermore, we asked about the most bothersome symptom (no symptoms at all, upper abdominal pain, reflux, abdominal distension, bowel problems).

Data on the number of endoscopies, antisecretory medication (H2 blockers and PPIs), H pylori eradication treatments, NSAIDs, hospitalisation, and visits to outpatient clinics were retrieved from population based databases—Odense Pharmacoepidemiological database21 and the Patients Administrative System in the County of Funen22 covering 100% of reimbursed prescriptions, all public hospital visits, and 95% of all endoscopies performed in the county (inhospital as well as outpatient clinic endoscopies). Virtually all inpatient medical care and most outpatient care in Denmark is provided by the public health authorities. Information at the individual level regarding date of contact, performed procedures, and discharge coding is available from the Patient Administrative System in the County of Funen, covering all in- and outpatient contacts at hospitals in the County of Funen. During the study period, PPIs were only available on prescription. All H2 receptor antagonists and ibuprofen 200 mg were available over the counter throughout the study period. However, by comparing gross volume sales figures from the Danish Medicines Agency with person identifiable prescriptions in the Odense Pharmacoepidemiological Database, we estimated that only 3% of H2 receptor antagonists and 12% of NSAIDs were not registered in the Odense Pharmacoepidemiological Database.

Information from the databases was linked at the individual level using a 10 digit personal identification code by which all Danish citizens are registered. Use of resources was registered from inclusion to 31 December 2002, death, exclusion, or leaving the county, whichever came first.

Outcome

The main outcome was the proportion of days without dyspeptic symptoms registered in diaries. Secondary outcomes were number of endoscopies, H pylori eradication treatments, antisecretory medication, hospitalisations, and visits to outpatient clinics during the entire follow up period. Other secondary outcomes were symptoms, patient satisfaction, and quality of life, recorded in the follow up questionnaire and visits to general practitioners, and sick leave days registered in the diaries.

Analyses

We analysed data by intention to treat whenever possible (number of endoscopies, H pylori eradication treatments, antisecretory medications, and hospital visits). Diary and questionnaire data were analysed using a per protocol approach

All tests were two sided. Group comparisons of rates and proportions were assessed by the χ2 test or the Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate. With a type 1 error of 5% and a power of 90%, the study could detect a 0.15 difference in the mean proportion of days without symptoms registered in the diaries (t test), a 0.25 difference in number of endoscopies/person, and a 56 defined daily dose (DDD) difference in mean use of antisecretory medication/person.

All analyses were repeated in predefined subgroups according to H pylori status, age, and presence of reflux symptoms at entry. Use of antisecretory medication was measured in DDD.23 Data were analysed by STATA 8.

RESULTS

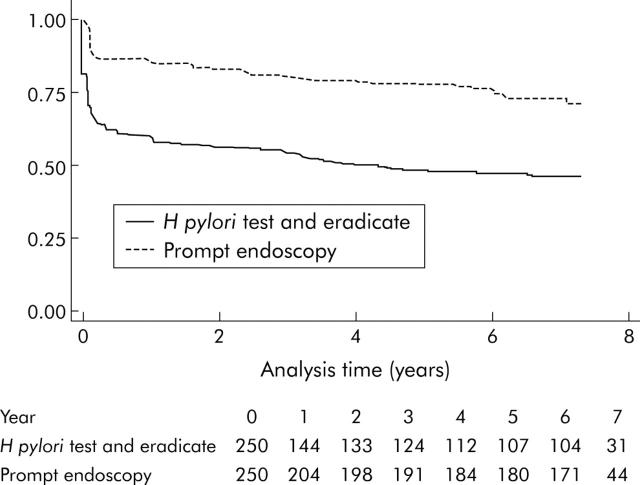

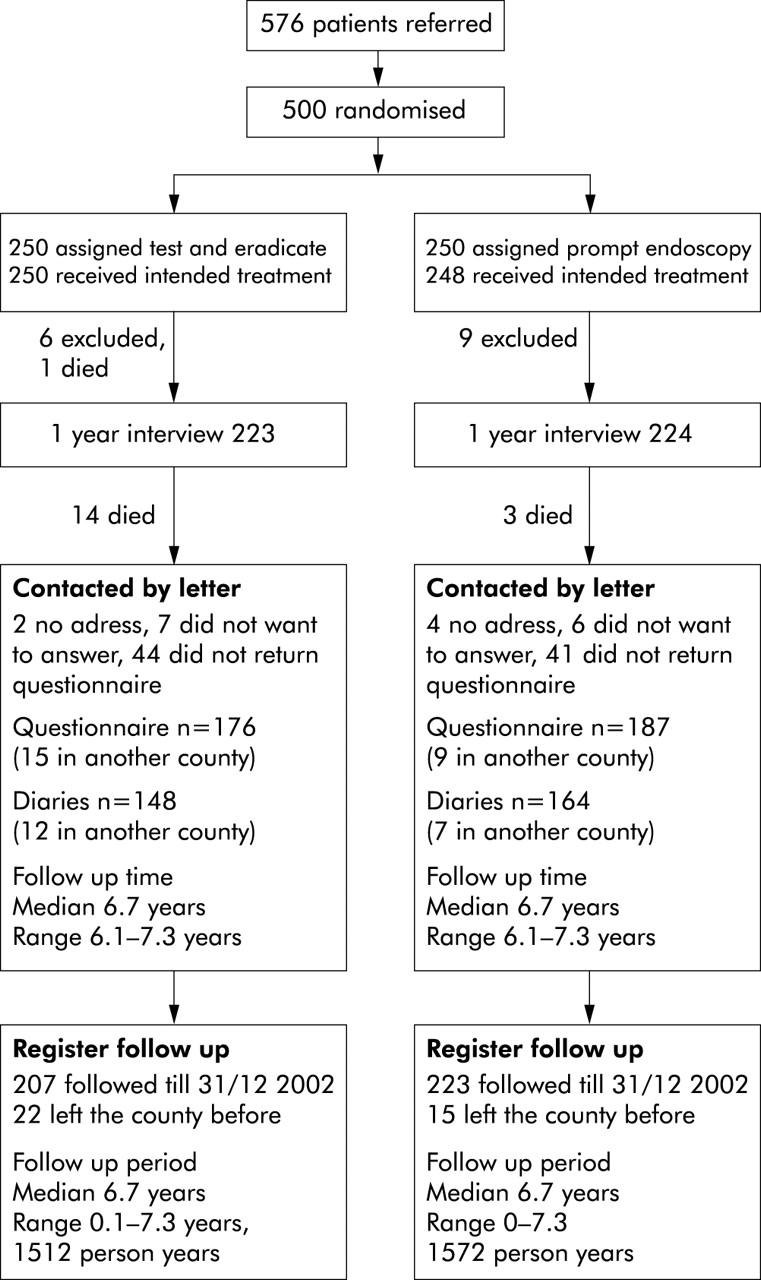

Sixty five general practitioners referred 576 patients to the study. A total of 500 patients were randomised: 250 to each group. At inclusion, median age was 45 years and 28% were infected by H pylori (table 1 ▶). Median duration of history of dyspepsia was five years (range 0–70) and median duration of the present episode was 2.5 months (range 3 days to 8 years). Details of the patients included and the first year of follow up have been described previously.17 Median follow up was 6.7 years (3084 person years) (fig 1 ▶).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at entry

| Test and eradicate group (n = 250) | Prompt endoscopy group (n = 250) | |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (y) (median (range)) | 44 (18–88) | 47 (19–84) |

| Sex (M/F) | 105/145 | 125/125 |

| History | ||

| History of dyspepsia (y) (median (range)) | 3.2 (0–50) | 7.9 (0–70) |

| Length of present episode (months) (median (range)) | 2.8 (0–180) | 2.5 (0–120) |

| Sick leave days in preceding month (median (range)) | 0 (0–30) | 0 (0–30) |

| NSAID use in past month | 53 (21%) | 48 (19%) |

| H pylori positive | 64 (26%) | 77 (31%) |

| Smoker | 114 (46%) | 117 (47%) |

| Previous PPI or H2 blocker therapy | 107 (43%) | 99 (40%) |

| Previous H pylori test | 0 | 3 (1%) |

| Previous endoscopy | 70 (28%) | 68 (27%) |

| Previous peptic ulcer | 20 (8%) | 22 (9%) |

| Previous oesophagitis | 11 (4%) | 13 (5%) |

| Effect of dyspepsia on lifestyle | ||

| No/minimal | 15 (6%) | 15 (6%) |

| Minor influence | 126 (54%) | 121 (48%) |

| Moderate influence | 99 (40%) | 110 (44%) |

| Debilitating symptoms | 0 | 4 (2%) |

| Dominant symptom complex | ||

| Heartburn and/or regurgitation | 84 (34%) | 75 (30%) |

| Epigastric pain | 86 (34%) | 101 (40%) |

| Nausea | 24 (10%) | 25 (10%) |

| Bloating | 56 (22%) | 49 (20%) |

NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

Six patients could not be contacted due to unknown address or emigration. Fifteen (6%) patients in the test and eradicate group and three (1%) in the endoscopy group died during follow up. None of the patients died of causes related to dyspeptic symptoms at entry. One patient died 3.5 years after inclusion due to colonic cancer, one 4.3 years after entry due to pancreatic cancer, one after 4.6 years of acute pancreatitis, and two after 4.5 and 4.6 years due to ileus. Six patients died of lung cancer, two of septicaemia, two of ischaemic heart disease, one of severe chronic obstructive lung disease, and there were two suicides.

Two patients had gastric cancer diagnosed at entry and were excluded from the study. A 72 year old male assigned to the test and eradicate strategy had oesophageal cancer diagnosed 2.6 years after inclusion. He did not die during follow up.

In the test and eradicate group, 176 (70%) patients answered the follow up questionnaire compared with 187 (75%) in the endoscopy group. The corresponding values for the diaries were 148 (59%) in the test and eradicate group and 164 (66%) in the prompt endoscopy group (fig 1 ▶).

We found no difference between the groups in the proportion of days with and without dyspeptic symptoms registered in the diaries. The proportion of days without dyspeptic symptoms was median 0.52 (interquartile range 0.10–0.88) in the test and eradicate group versus 0.64 (0.14–0.90) in the prompt endoscopy group (p = 0.27) (mean difference 0.05 (95% confidence interval (CI) −0.03–0.14)).

There were no differences between the two groups in scores on the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale, satisfaction with dyspepsia related health scale quality of life, or most bothersome symptom stated neither in the first questionnaire (table 2 ▶) nor in the second (data not presented).

Table 2.

Symptoms, quality of life, and patient satisfaction with dyspepsia related health after 6.7 years

| Test and eradicate group (n = 176) | Prompt endoscopy group (n = 187) | p Value | |

| Median (IQR) score on rating scale | |||

| Gastrointestinal symptom rating scale* | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) | 0.68 |

| Psychological general well being index† | 105 (89–116) | 106 (92–118) | 0.49 |

| Satisfaction with dyspepsia related health‡ | 13 (11–20) | 14 (11–20) | 0.87 |

| Most bothersome symptom | |||

| No symptoms | 52 (30%) | 57 (30%) | 0.80 |

| Upper abdominal pain | 21 (12%) | 32 (17%) | |

| Heartburn and/or regurgitation | 36 (20%) | 34 (18%) | |

| Distension | 24 (14%) | 23 (12%) | |

| Bowel problems | 15 (9%) | 14 (7%) | |

| Inconclusive answer | 28 (16%) | 27 (14%) |

*Decreasing value means decreasing symptoms.

†Increasing value means increasing quality of life.

‡Increasing value means increasing satisfaction with dyspepsia related health.

IQR, interquartile range.

The mean number of endoscopies in the test and eradicate group was 0.88 per patient compared with 1.50 per patient in the endoscopy group, including the initial endoscopy at randomisation (mean difference 0.62 endoscopies per patient (95% CI 0.38–0.86); p<0.0000). Use of antisecretory medication was lower in the test and eradicate group (mean difference for the entire follow up period 102 DDD per patient (95% CI −1 to 205); p = 0.026) and the use of eradication treatments was higher (mean difference 0.08 treatments per patient (95% CI −0.16 to 0.00); p = 0.047) compared with the prompt endoscopy group (table 3 ▶). We found no difference in visits to outpatient clinics or hospitalisations registered during the complete follow up period, or in number of visits to general practitioners or number of sick leave days reported in the diaries (table 3 ▶). Of 500 patients, 314 (63%) redeemed at least one prescription of NSAIDs during follow up (median use 49 DDD) with no difference between the groups.

Table 3.

Mean (per patient) use of resources

| Test and eradicate group (n = 250) | Prompt endoscopy group (n = 250) | Difference | p (Mann-Whitney) | |

| Endoscopies* | 0.88 (0.68–1.08) | 1.50 (1.36–1.63) | 0.62 (0.38–0.86) | 0.0000 |

| Eradication therapies* | 0.29 (0.23–0.35) | 0.21 (0.16–0.27) | −0.08 (–0.16–0.00) | 0.047 |

| PPIs and H2 blockers (DDD)* | 271 (205–338) | 373 (294–453) | 102 (−1–205) | 0.026 |

| Visits to outpatient clinics* | ||||

| Gastrointestinal related† | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | −0.2 (−0.6–0.3) | 0.73 |

| Other | 10.3 (8.1–12.5) | 9.6 (7.8–11.4) | −0.7 (−3.6–2.1) | 0.78 |

| Days in hospital* | ||||

| Gastrointestinal related† | 1.5 (0.8–2.2) | 1.0 (0.5–1.4) | −0.5 (−1.4–0.3) | 0.54 |

| Other | 15.5 (8.3–22.8) | 13.5 (3.3–23.8) | −2.0 (−14.5–10.5) | 0.39 |

| Sick leave days‡ | ||||

| Dyspepsia related | 0.34 (0.10– 0.59) | 0.74 (0.10–1.38) | 0.39 (−0.32–1.10) | 0.89 |

| Other | 1.72 (0.41–3.02) | 2.77 (1.01–4.53) | 1.05 (−1.17–3.27) | 1.00 |

| Visits to GP‡ | ||||

| Dyspepsia related | 0.34 (0.13–0.55) | 0.23 (0.13–0.33) | −0.12 (−0.34–0.11) | 0.73 |

| Other | 1.03 (0.68–1.38) | 0.95 (0.67–1.22) | −0.09 (−0.53–0.35) | 0.70 |

Values are mean (95% confidence interval).

*Register based information for 500 patients with a total of 3084 observation years.

†Main diagnosis ICD10 K000-K938 or C150–C269.

‡Diary based information for 312 patients, 3 month/patient.

DDD, defined daily doses; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors.

Among the 250 patients assigned to the test and eradicate strategy, 131 (52%) were investigated by endoscopy, and among the 250 patients assigned to prompt endoscopy, 64 (26%) had at least two endoscopies (fig 2 ▶). Eleven patients were found to have peptic ulcer disease. All of these patients were H pylori negative and 9/11 (82%) used NSAIDs. Eight were diagnosed at entry or at the one month follow up. Three had NSAID related gastric ulcers diagnosed 1.3–6.5 years after entry (one uncomplicated and two bleeding). Among the 250 patients assigned to prompt endoscopy, 48 (19%) had uncomplicated peptic ulcer diagnosed, of which 47 were diagnosed at entry and one H pylori positive patient after 5.7 years. No patient had complicated ulcers. During the first year of follow up, 104 patients were given H pylori eradication therapy (64 in the test and eradicate group) and eradication was achieved in 99 (87%). After 6.7 years, 44/76 (58%) H pylori positive patients among patients assigned prompt endoscopy had been treated by H pylori eradication therapy. Thirty of 44 were treated due to peptic ulcers found at inclusion.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Mayer plot of follow up free of endoscopy for patients assigned to Helicobacter pylori test and eradicate, and follow up free of second endoscopy for patients assigned to prompt endoscopy.

Subgroup analysis according to H pylori status, presence of reflux symptoms, or age at entry showed that the number of endoscopies was lower in all subgroups in the test and eradicate group compared with the prompt endoscopy group (table 4 ▶). In the test and eradicate group, use of antisecretory medication was reduced among patients without reflux symptoms and among H pylori positive patients. In the other subgroups, mean use of antisecretory medication was lowest in the test and eradicate group but the differences were not statistically significant. We found no difference in proportion of days without dyspeptic symptoms (table 4 ▶) and no difference in the remaining subgroup analyses performed in parallel with analysis of the whole study group (data not presented).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis

| Test and eradicate | Prompt endoscopy | Difference | p (Mann-Whitney) | |

| Proportion of days without dyspeptic symptoms (median (IQR)) | ||||

| H pylori positive (n = 38/48) | 0.24 (0.00–0.86) | 0.50 (0.10–0.88) | 0.11 (−0.06 to 0.28) | 0.19 |

| H pylori negative (n = 116/110) | 0.62 (0.14–0.90) | 0.69 (0.21–0.90) | 0.04 (−0.06 to 0.14) | 0.50 |

| Reflux symptoms (n = 56/55) | 0.50 (0.14–0.81) | 0.62 (0.14–0.86) | 0.06 (−0.08 to 0.19) | 0.43 |

| No reflux symptoms (n = 92/109) | 0.52 (0.08–0.92) | 0.67 (0.19–0.90) | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.16) | 0.43 |

| >45 y (n = 76/93) | 0.33 (0.00–0.90) | 0.57 (0.14–0.86) | 0.01 (−0.11 to 0.13) | 0.13 |

| ⩽45 y (n = 72/71) | 0.62 (0.33–0.86) | 0.71 (0.19–0.90) | 0.10 (−0.02 to 0.22) | 0.83 |

| Endoscopies (mean (95% CI))* | ||||

| H pylori positive (n = 64/76) | 1.19 (0.88–1.50) | 1.84 (1.57–2.11) | 0.65 (0.25 to 1.05) | 0.0002 |

| H pylori negative (n = 186/174) | 0.77 (0.52–1.02) | 1.34 (1.19–1.50) | 0.58 (0.28 to 0.87) | 0.0000 |

| Reflux symptoms (n = 84/75) | 0.94 (0.71–1.17) | 1.30 (1.13–1.48) | 0.37 (0.07 to 0.66) | 0.0004 |

| No reflux symptoms (n = 166/175) | 0.84 (0.56–1.12) | 1.58 (1.40–1.75) | 0.73 (0.41 to 1.06) | 0.0000 |

| >45 y (n = 117/128) | 1.22 (0.83–1.61) | 1.65 (1.43–1.87) | 0.43 (−0.01 to 0.87) | 0.0000 |

| ⩽45 y (n = 133/122) | 0.57 (0.44–0.70) | 1.33 (1.19–1.48) | 0.76 (0.57 to 0.96) | 0.0000 |

| Antisecretory medication (mean DDD (95% CI))* | ||||

| H pylori positive (n = 64/76) | 320 (177–463) | 416 (262–569) | 96 (−115 to 307) | 0.046 |

| H pylori negative (n = 186/174) | 254 (179–329) | 355 (262–448) | 101 (−17 to 219) | 0.22 |

| Reflux symptoms (n = 84/75) | 471 (314–627) | 578 (389–767) | 107 (−134 to 349) | 0.51 |

| No reflux symptoms (n = 166/175) | 170 (113–227) | 286 (209–363) | 116 (19 to 212) | 0.002 |

| >45 y (n = 117/128) | 358 (253–464) | 512 (379–644) | 153 (−16 to 324) | 0.11 |

| ⩽45 y (n = 133/122) | 195 (112–278) | 229 (151–306) | 34 (−80 to 148) | 0.14 |

*Register based information for 500 patients with a total of 3084 observation years.

IQR, interquartile range; CI, confidence interval; DDD, defined daily doses.

DISCUSSION

In this 6.7 year perspective study, we found that the H pylori test and eradicate strategy was as efficient as prompt endoscopy for the management of dyspeptic patients in terms of dyspeptic symptoms, satisfaction with dyspepsia related health, and quality of life. We also found that the number of endoscopies and use of antisecretory medication were lower in patients assigned to the test and eradicate strategy than among patients assigned to prompt endoscopy.

The strength of the study is the randomised design and the long term follow up, with detailed registration throughout the study of the number of endoscopies and hospitalisations and of redeemed prescriptions for antisecretory medications and H pylori eradication treatments.

Patients were recruited in primary care and were randomised and investigated by the study coordinator in an outpatient clinic. The fact that patients were not completely under the care of general practitioners during the first year is a possible limitation of our study, although results from the one year follow up were confirmed in a Dutch investigation in which randomisation and management was performed in primary care by general practitioners.14 In the present long term follow up, patients had no contact with the study and were managed exclusively by their general practitioners in 2601/3084 (84%) of the observation years.

Three other randomised studies have compared a test and eradicate strategy with prompt endoscopy for the management of dyspeptic patients. Arents et al included dyspeptic patients in primary care,14 McColl et al included dyspeptic patients younger than 55 years from secondary care,15 and Heaney et al included H pylori positive dyspeptic patients younger than 45 years from secondary care.16 All were followed up for one year, and all found that patients in the test and eradicate group underwent fewer endoscopies and had either less dyspeptic symptoms16 or there was no difference in dyspeptic symptoms compared with patients managed by prompt endoscopy.14,15 Our study adds further to the long term stability of these findings. As in McColl’s study,15 we found that the results were valid in subgroup analyses of H pylori positive and H pylori negative patients and in patients with and without reflux symptoms at entry. Furthermore, we found similar results in patients under and over 45 years of age.

After one year, more patients treated with the test and eradicate strategy expressed dissatisfaction with the management than patients treated by prompt endoscopy (12% v 4%).17 These dissatisfied patients do not seem to have influenced the use of resources significantly. In the present follow up, we found no difference between the two groups regarding satisfaction with dyspepsia related health. Due to the long time span, we did not ask patients specifically about satisfaction with management performed 6.7 years ago.

Use of antisecretory medication was reduced in patients assigned to the test and eradicate strategy compared with patients assigned to prompt endoscopy. Reduction was found in all subgroups, although only to a minor degree in patients younger than 45 years, and only statistically significant among patients without reflux symptoms and among H pylori positive patients. In parallel, Arents et al found reduced use of antisecretory medication among patients in the test and eradicate strategy compared with the endoscopy strategy.14 Arents et al recruited dyspeptic patients without reflux symptoms and collected medication data from pharmacy records. Two other studies found no difference in the proportion of patients who used antisecretory medication 12 months following management by a test and eradicate strategy compared with prompt endoscopy.15,16 In both studies patients were interviewed regarding use of medication.

In patients assigned to prompt endoscopy, 19% had a peptic ulcer diagnosed compared with 8% of all endoscoped patients in the test and eradicate group. These patients were all H pylori negative, and most used NSAIDs, indicating that a test and eradicate strategy correctly identifies and treats patients with H pylori related peptic ulcers. The two patients in the test and eradicate group with a bleeding peptic ulcer were taking NSAIDs. A main concern regarding a test and eradicate strategy is the risk of missing an early gastric cancer. Two patients had gastric cancer diagnosed at entry, and 2.6 years after inclusion one patient was diagnosed with oesophageal cancer. We found no further gastric or oesophageal malignancies. More patients in the test and eradicate group died. None of the patients died of causes related to dyspeptic symptoms at entry, and the observed difference was most probably a chance finding. The study did not have the power to estimate the risk differences between the two management strategies for early detection of gastric cancer, cause of death, or risk of developing complicated peptic ulcer. However, both strategies appeared safe.

The cost effectiveness of a test and eradicate strategy is believed to depend on effects related to H pylori infected persons and therefore to depend on the prevalence of H pylori infection.5,6,24 However, we found equal reductions in the number of endoscopies and use of antisecretory medication in the test and eradicate group, both among patients who were H pylori positive and H pylori negative at inclusion (table 4 ▶). The reason for this is unknown but may be related to a reassurance effect of management with the test and eradicate strategy, but may also be due to chance. However, the findings challenge the assumption that the cost effectiveness of a test and eradicate strategy is confined to H pylori infected persons.

The trial was not designed to estimate the costs of the management strategies. We had no access to valid data regarding the use of H pylori testing but the study provides important information regarding the use of endoscopy and other health care resources. Endoscopy is one of the most important variables influencing cost effectiveness in the management strategy for dyspeptic patients.4 In combination with reduced use of antisecretory medication, our findings indicate that a test and eradicate strategy in a long term perspective is more cost effective than prompt endoscopy. Whether or not a H pylori test and eradicate strategy is cost effective in the long term compared with strategies other than prompt endoscopy is still not known.

Abbreviations

NSAID, non-steroidal-anti-inflammatory drug

DDD, defined daily doses

PPI, proton pump inhibitor

REFERENCES

- 1.Delaney BC, Moayyedi P, Forman D. Initial management strategies for dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003:CD001961. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Talley NJ, Silverstein MD, Agreus L, et al. AGA technical review: evaluation of dyspepsia. American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 1998;114:582–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malfertheiner P , Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht 2-2000 Consensus Report. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:167–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, Hirth RA, et al. Alternative management strategies for patients with suspected peptic ulcer disease. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:260–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladabaum U , Chey WD, Scheiman JM, et al. Reappraisal of non-invasive management strategies for uninvestigated dyspepsia: a cost-minimization analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiegel BM, Vakil NB, Ofman JJ. Dyspepsia management in primary care: a decision analysis of competing strategies. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1270–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein MD, Petterson T, Talley NJ. Initial endoscopy or empirical therapy with or without testing for Helicobacter pylori for dyspepsia: a decision analysis. Gastroenterology 1996;110:72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delaney BC, Wilson S, Roalfe A, et al. Cost effectiveness of initial endoscopy for dyspepsia in patients over age 50 years: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Lancet 2000;356:1965–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delaney BC, Wilson S, Roalfe A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of Helicobacter pylori testing and endoscopy for dyspepsia in primary care. BMJ 2001;322:898–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bytzer P , Hansen JM, Schaffalitzky-De MO. Empirical H2-blocker therapy or prompt endoscopy in management of dyspepsia. Lancet 1994;343:811–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabeneck L , Souchek J, Wristers K, et al. A double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:3045–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiba N , Van Zanten SJ, Sinclair P, et al. Treating Helicobacter pylori infection in primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia: the Canadian adult dyspepsia empiric treatment-Helicobacter pylori positive (CADET-Hp) randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002;324:1012–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manes G , Menchise A, de Nucci C, et al. Empirical prescribing for dyspepsia: randomised controlled trial of test and treat versus omeprazole treatment. BMJ 2003;326:1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arents NL, Thijs JC, van Zwet AA, et al. Approach to treatment of dyspepsia in primary care: a randomized trial comparing “test-and-treat” with prompt endoscopy. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1606–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McColl KE, Murray LS, Gillen D, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopy with testing for Helicobacter pylori compared with non-invasive H pylori testing alone in the management of dyspepsia. BMJ 2002;324:999–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heaney A , Collins JS, Watson RG, et al. A prospective randomised trial of a “test and treat” policy versus endoscopy based management in young Helicobacter pylori positive patients with ulcer-like dyspepsia, referred to a hospital clinic. Gut 1999;45:186–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lassen AT, Pedersen FM, Bytzer P, et al. Helicobacter pylori test-and-eradicate versus prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients: a randomised trial. Lancet 2000;356:455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, et al. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res 1998;7:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabeneck L , Cook KF, Wristers K, et al. SODA (severity of dyspepsia assessment): a new effective outcome measure for dyspepsia-related health. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:755–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupuy HJ. The Psychological General Well-being (PGWB) Index. In: Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CF, et al, eds. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. New York: Le Jacq Publishing Inc, 1984:170–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Gaist D , Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish prescription registries. Dan Med Bull 1997;44:445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frank L . Epidemiology. When an entire country is a cohort. Science 2000;287:2398–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Classification index including Defined Daily Doses (DDD) for plain substances. WHO collaborating center for drug statistical methodology. Oslo: Norweigian Institute of Public Health, 1995.

- 24.Talley NJ. Review article: dyspepsia: how to manage and how to treat? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16 (suppl 4) :95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]