Abstract

Patients with functional gut disorders, irritable bowel disease, and related syndromes frequently attribute their symptoms to intestinal gas. While patients are usually convinced of their interpretation, the doctor has few arguments to confirm or refute it, and in this context intestinal gas has become a myth. Studies of intestinal gas dynamics have demonstrated subtle dysfunctions in intestinal motility. Hopefully, extension of these studies may help both in the classification of patients complaining of gas symptoms based on pathophysiological mechanisms, and in identification of objective markers to test mechanistically oriented treatment options.

Keywords: intestinal gas, intestinal gas dynamics

Patients with functional gut disorders, irritable bowel disease, and related syndromes frequently attribute their symptoms to intestinal gas. While patients are usually convinced of their interpretation, the doctor has few arguments to confirm or refute it, and in this context intestinal gas has become a myth. Levitt’s group initiated a scientific approach to this problem and produced most of the information about gas metabolism we have today.1 Still, their work is not familiar to the practicing gastroenterologist and indeed, the classical chapter on intestinal gas has disappeared from major textbooks. Fifteen years ago, in the way of exploring gut stimuli that could be responsible for abdominal symptoms, we retook the intestinal gas lead from a different perspective, exploring intestinal gas handling and the production of symptoms.

EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES

There is a considerable amount of information in relation to transit of solid and liquid components of chyme along the whole gastrointestinal tract but in contrast, the fate of gas, the third element, remains obscure. Intestinal gas dynamics have recently been investigated using a gas challenge test: exogenous gas is continuously infused into the intestine while measuring gas evacuation, girth, and abdominal symptoms. With this technique a series of mechanistic studies have been carried out both in healthy subjects and in patients with gas symptoms.

Lessons from healthy subjects

The first important observation in an initial dose-response study was that healthy subjects evacuate as much gas as infused without discomfort.2 Indeed, jejunal gas infusion at a rate up to 30 ml/min (that is, 1.8 l/h) is well tolerated by the majority of the healthy population. However, intraluminal gas displacement is not a passive process. Further studies rather indicated that the gut actively propulses gas because transit of gas down the gastrointestinal tract is more effective in the erect position, opposing flotation forces, than when supine.3 Transit of gas, like that of solids and liquids, is modulated by a series of reflex mechanisms: intraluminal nutrients, particularly lipids, delay gas transit,4 whereas mechanical stimulation of the gut, for instance mild rectal distension, has a strong prokinetic effect.5

“The gut actively propulses gas because transit of gas down the gastrointestinal tract is more effective in the erect position”

In the precedent studies it became apparent that gas is moved along the gut independently of solids and liquids. Conceivably, large masses of low resistance gas are displaced by subtle changes in gut tone and capacitance, proximal contraction and distal relaxation, that do not affect solid-liquid contents.6 Gas transit is normally very effective but if a certain amount of gas is retained within the gut, subjects may develop abdominal distension and symptoms. Different experimental models of gas retention were used to show that while abdominal distension is related to the volume of gas within the gut, perception of abdominal symptoms depends both on intestinal motor activity (gas is better tolerated when the gut is relaxed)7 and on the intraluminal distribution of gas (gas is better tolerated within the colon than within the long, but poorly compliant, small intestine).8

Observations in patients complaining of gas symptoms

Using the same methodology it was shown that patients complaining of abdominal bloating, either with irritable bowel syndrome or functional bloating, have impaired gas transit and develop intestinal gas retention, abdominal distension, and/or abdominal symptoms in response to gas loads (12 ml/min jejunal gas infusion for 2–3 hours) that are well tolerated by healthy subjects.4,9,10 Interestingly, symptoms induced by the gas challenge test in patients by and large replicate their customary complaints. Scintigraphic studies using gas labelled with radioactive xenon produced striking data indicating that the small bowel is responsible for impaired gas transit in these patients, in contrast with the common idea of gas being retained in the colon.11 The ileocaecal region is an area with sphincteric function likely implicated in this dysfunction. However, very elaborate studies with gas infusion at various levels of the gut showed that gas retention is due to impaired propulsion in more proximal parts of the small bowel because while jejunal gas loads were retained, clearance of gas directly infused into the distal ileum or caecum was normal.

“The small bowel is responsible for impaired gas transit in these patients, in contrast with the common idea of gas being retained in the colon”

Impaired gas clearance in these patients is related to abnormal gut reflexes: the prokinetic effect of gut distension is impaired12 and the inhibitory effect of intestinal lipids is upregulated,4 and both effects, reduced stimulation and increased inhibition, contribute to delayed gas transit and retention.

FROM THE LAB TO THE CLINICAL ARENA

What is the clinical relevance of intestinal gas? In a small proportion of patients gas in the gut is very relevant to their symptoms but in the majority of patients complaining of gas symptoms the relation is not as clear.

The obvious gas related syndromes

Some clinical conditions, such as aerophagia, excessive or odoriferous flatus, and impaired anal evacuation, are clearly related to troubles with gas in the gut.

Aerophagia

Some patients complain of excessive eructation, as if their gastric production of gas is unlimited. Really, these patients inadvertently swallow air that accumulates in the stomach and is then released by belching, with patient satisfaction.1 Frequently, the process is triggered by a basal dyspeptic-type symptom of epigastric fullness that patients misinterpret as excessive gas in the stomach, and during repetitive and ineffective attempts of belching, air is introduced into the stomach with increasing discomfort. The patient’s misconception is reinforced by the partial relief experienced when eructation finally occurs. In most of the cases a clear explanation resolves the problem but in some patients psychological abnormalities may be involved, requiring special management.

Excessive and/or bad smelling flatus

These patients pass large volumes of sometimes odoriferous gas per anus. Gas evacuation depends on the volume of gas produced by colonic bacteria during fermentation of unabsorbed food residues arriving into the colon.1 Hence the volume of gas depends on diet, and most subjects may experience flatulence after eating foods rich in fermentable residues, such as beans. The amount of gas also depends on the composition of the colonic flora, which is very stable in each subject but exhibits high interindividual variations, so that some subjects are prone to excessive gas production and evacuation.1 These subjects do not complain of abdominal symptoms unless they have associated irritable bowel syndrome, because healthy subjects propulse and evacuate large intraluminal gas loads without symptoms.

“The amount of gas also depends on the composition of the colonic flora, which is very stable in each subject but exhibits high interindividual variations, so that some subjects are prone to excessive gas production and evacuation”

Since modification of colonic flora is not yet an effective option, treatment is focused on dietary instructions, helping the patient identify the high flatulogenic offending foodstuffs.13

Impaired anal evacuation

Self restraint anal gas evacuation in healthy subjects produces gas retention,7 and this mechanism may also operate in patients with impaired anal evacuation due to functional outlet obstruction. Furthermore, faecal retention would prolong the fermentation process, increasing gas production. In contrast with patients with excessive flatus, these patients complain of difficult evacuation and abdominal gas retention, and the problem can be resolved by biofeedback retraining.14

Abdominal gas symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome and related syndromes

Gas related symptoms are the most frequent and troublesome complaints in patients with functional intestinal disorders, particularly irritable bowel syndrome and functional bloating, but the situation here is far less clear than in the conditions described above. Experimental studies in these patients have demonstrated a series of abnormalities in intestinal handling of gas loads but how do these abnormalities relate to symptoms? The clinical relevance of intestinal gas in this context can be established by addressing a series of questions.

Do these patients produce more intestinal gas?

Gas production was initially measured by Levitt’s group using a washout technique, and was found to be normal in patients.15 Hydrogen, which accounts for a large proportion of colonic gas production, is partly absorbed into the blood and excreted by breath.1 A more recent and largely quoted study measured gas excretion (breath plus anal) by indirect calorimetry in irritable bowel syndrome patients on a standard diet and showed that hydrogen excreted was increased but the total gas volume excreted (hydrogen plus methane) was not different than in healthy controls.16 Indirect evaluation of hydrogen production by breath tests has shown either normal production17 or increased production, attributed to various causes, such as hyperactive gas producing colonic flora,16 small bowel bacterial overgrowth,18 or small bowel malabsorption.19 The level of evidence supporting these interpretations is questionable. Nevertheless, it seems that the total volume of gas produced in these patients is not much larger than in healthy subjects.

Do these patients have more gas within the gut?

Three independent studies showed that the gas surface in plain abdominal radiographs was 28%–118% larger in irritable bowel syndrome patients than in controls.20–22 As the normal volume of intestinal gas is approximately 200 ml,9,10,15 this difference would hardly justify the symptoms. Furthermore, other studies using computed tomography23 or the washout technique9,10,15 could not detect differences between patients complaining of bloating and healthy controls.

Hence impaired gas transit in these patients does not result in global gas retention. Conceivably, the abnormalities detected by the gas transit studies affect intraluminal gas distribution and result in segmental gas pooling and focal distension, without net increments in total gas volume.

Is abdominal distension a fact?

Abdominal distension is the most common gas symptom in patients with functional intestinal disorders. However, this patient claim is difficult to verify. Frequently, these patients report that distension develops during the day and resolves after overnight rest, and this variability may be the key to substantiate the subjective sensation. Several studies measuring girth changes with a tape measure,23,24 computed tomography,23 and, more recently, inductance plethysmography,25 have shown that, indeed, the subjective sensation is associated with objective abdominal distension.

“Patients with bloating do have objective abdominal distension but it may not necessarily be due to a true increment in intra-abdominal volume”

The abdominal wall normally adapts to its content. It has been recently shown that an intra-abdominal volume load, produced by colonic gas infusion, induces in healthy subjects an increment in tonic activity of the abdominal muscles that can be measured by electromyography,26 and this response is probably mediated via viscerosomatic reflexes.27 This adaptation of the abdominal wall to intra-abdominal volume loads is impaired in patients complaining of bloating who fail to contract their abdominal muscles, and this abnormal response is associated with exaggerated abdominal distension and bloating.26 Hence patients with bloating do have objective abdominal distension but it may not necessarily be due to a true increment in intra-abdominal volume, but to abdominal wall dystony with abdominal redistribution and protrusion of the anterior wall.

The ultimate question: is it really gas that matters?

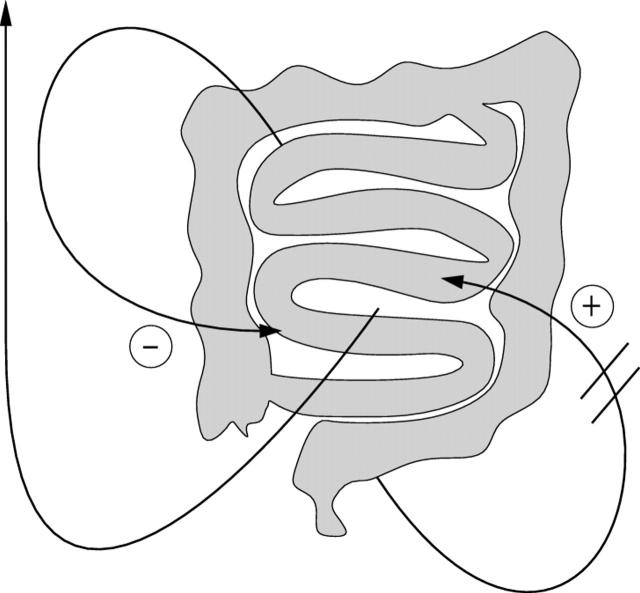

Gas transit studies have consistently shown that patients complaining of intestinal gas symptoms have impaired handling of intestinal contents, related to abnormal gut reflexes, which may result in segmental pooling and focal gut distension (fig 1 ▶). Additional evidence indicates that these patients also have a sensory dysfunction with increased perception of intraluminal stimuli.28,29 As described above, recent data further suggest that viscerosomatic reflexes controlling abdominal wall tone may also be affected, so that segmental pooling within the gut may lead to abdominal wall dystony and distension. However, this does not imply that gas is necessarily the offending element, but rather other intraluminal components could trigger the abnormal responses and thus be responsible for the abdominal symptoms that patients misinterpret and attribute to intestinal gas. The main contribution of gas studies has been demonstration of subtle dysfunctions of intestinal motility that were missed, or at least not consistently observed, with conventional methodologies. Hopefully, extension of these studies may help both in the classification of patients complaining of gas symptoms based on pathophysiological mechanisms, and in identification of objective markers to test mechanistically oriented treatment options.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of gas symptoms. Abnormal reflexes, exaggerated inhibition, and defective stimulation result in impaired handling of intraluminal contents with focal pooling and distension, which in the presence of hypersensitivity may produce symptoms that the patient attributes to intestinal gas.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institute of Health USA (grant DK 57064), the Spanish Ministry of Education (grant BFI 2002-03413), and the Instituto Carlos III (grant C03/02). The author thanks Gloria Santaliestra for secretarial assistance.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levitt MD, Bond JH, Levitt DG. Gastrointestinal gas. In: Johnson LR, ed. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven, 1981:497–502.

- 2.Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada J-R. Intestinal gas dynamics and tolerance in humans. Gastroenterology 1998;115:542–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dainese R, Serra J, Azpiroz F, et al. Influence of body posture on intestinal transit of gas. Gut 2003;52:971–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serra J, Salvioli B, Azpiroz F, et al. Lipid-induced intestinal gas retention in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;123:700–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harder H, Serra J, Azpiroz F, et al. Reflex control of intestinal gas dynamics and tolerance. Am J Physiol 2004;286:G89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tremolaterra F, Serra J, Azpiroz F, et al. Intestinal tone and gas motion. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2003;15:581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Mechanisms of intestinal gas retention in humans: impaired propulsion versus obstructed evacuation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2001;281:G138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harder H, Serra J, Azpiroz F, et al. Intestinal gas distribution determines abdominal symptoms. Gut 2003;52:1708–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada J-R. Impaired transit and tolerance of intestinal gas in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2001;48:14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caldarella MP, Serra J, Azpiroz F, et al. Prokinetic effects of neostigmine in patients with intestinal gas retention. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1748–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salvioli B, Serra J, Azpiroz F, et al. Origin of gas retention in patients with bloating. Gastroenterology 2005;128:574–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passos MC, Serra J, Azpiroz F, et al. Impaired reflex control of intestinal gas transit in patients with abdominal bloating. Gut 2005;54:344–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azpiroz F, Serra J. Treatment of excessive intestinal gas. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2004;7:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azpiroz F, Enck P, Whitehead WE. Anorectal functional testing. Review of a collective experience. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasser RB, Bond JH, Levitt MD. The role of intestinal gas in functional abdominal pain. N Engl J Med 1975;293:524–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King TS, Elia M, Hunter JO. Abnormal colonic fermentation in irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 1998;352:1187–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haderstorfer B, Whitehead WE, Schuster MM. Intestinal gas production from bacterial fermentation of undigested carbohydrate in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1989;84:375–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome. a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:412–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rumessen JJ, Gudmand-Hoyer E. Functional bowel disease: malabsorption and abdominal distress after ingestion of fructose, sorbitol, and fructose-sorbitol mixtures. Gastroenterology 1988;95:694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poynard T, Hernandez M, Xu P, et al. Visible abdominal distension and gas surface: description of an automatic method of evaluation and application to patients with irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1992;4:831–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chami TN, Schuster MM, Bohlman ME, et al. A simple radiologic method to estimate the quantity of bowel gas. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:599–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koide A, Yamaguchi T, Odaka T, et al. Quantitative analysis of bowel gas using plain abdominal radiograph in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxton DG, Martin DF, Whorwell P, et al. Abdominal distension in female patients with irritable bowel syndrome: exploration of possible mechanisms. Gut 1991;32:662–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan SN. A prospective study of unexplained visible abdominal bloating. N Z Med J 1994;1:428–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lea R, Whorwell P, Reilly B, et al. Abdominal distension in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): diurnal variation and its relationship to abdominal bloating. Gut 2003;52 (suppl VI) :A32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tremolaterra F, Serra J, Azpiroz F, et al. Bloating and abdominal wall dystony. Gastroenterology 2004;126:A53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez V, Thakur S, Mogil J. Differential effects of chemical and mechanical colonic irritation on behavioral pain response to intraperitoneal acetic acid in mice. Pain 1999;81:179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azpiroz F. Gastrointestinal perception: pathophysiological implications. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002;14:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kellow JE, Delvaux M, Azpiroz F, et al. Principles of applied neurogastroenterology: physiology/motility-sensation. Gut 1999;45 (suppl II) :17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]