SUMMARY

The increased risk of active tuberculosis (TB) associated with infliximab makes necessary a screen for active and latent TB before this or other anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) treatment is begun in patients with Crohn’s disease. This paper outlines how such screening should be undertaken, and how to decide which patients need antituberculous treatment or chemoprophylaxis before infliximab. All patients need a careful history for TB and a chest x ray. The minority of patients with a history of TB or an abnormal chest x ray should be referred for assessment by a TB specialist. Of the remainder, those with Crohn’s disease who are on immunosuppressive therapy do not require tuberculin testing. Comparison of their risk of TB while on anti-TNF therapy with the risks of chemoprophylaxis induced hepatitis indicates that black Africans aged over 15 years, South Asians born outside the UK, and other ethnic groups resident in the UK for less than five years should be considered for chemoprophylaxis with isoniazid for six months. For how to minimise the risk of TB in the small minority of patients with inflammatory bowel disease not on immunosuppressive treatment, readers are referred to the more detailed guidelines published in Thorax.1

INTRODUCTION

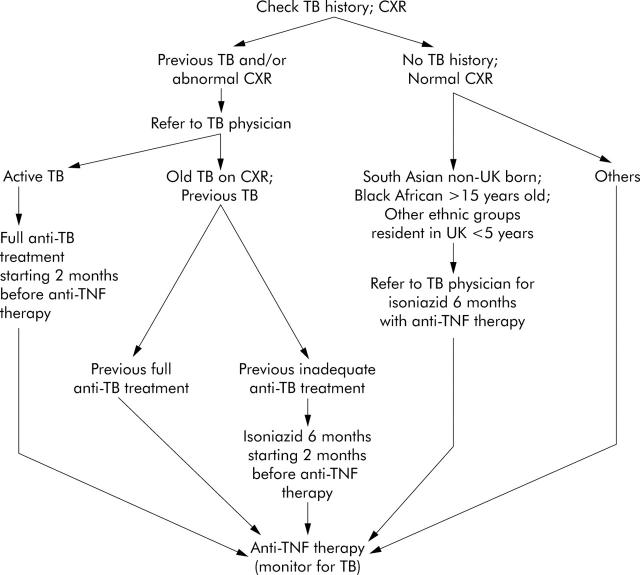

Infliximab is of proven benefit in the treatment of chronic active Crohn’s disease2 as well as in rheumatoid arthritis3 and ankylosing spondylitis4; preliminary data suggest it may also have a therapeutic role in refractory active ulcerative colitis.5–7 An increased risk of tuberculosis (TB) was noted soon after the introduction of infliximab in the late 1990s. To address the question of how best to prevent TB in patients needing infliximab and other anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) therapies, the British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee formed a subcommittee chaired by Professor Peter Ormerod and comprising also representatives of the British Society of Rheumatology and British Society of Gastroenterology (DSR). The full recommendations of this group, and their rationale, are reported in Thorax1 (also online at http://thorax.bmjjournals.com/cgi/rapidpdf/thx.2005.046797v1). This brief article aims to bring to the attention of gastroenterologists the principal conclusions as they relate specifically to the management of patients with Crohn’s disease; to facilitate this aim, an algorithm which outlines the approach to minimising the risk of TB is provided (fig 1 ▶).

Figure 1.

Algorithm to indicate the approach to prevention of tuberculosis (TB) in patients on immunosuppressants who need infliximab or other anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy for Crohn’s disease. The high incidence of anergy in patients with Crohn’s disease who take immunosuppressants14,15 makes tuberculin skin testing unreliable and unnecessary. The decision about TB chemoprophylaxis in individual patients with no history of TB and a normal chest x ray (CXR) is dependent on a comparison of their ethnicity related risk of acquiring TB during anti-TNF therapy and the risk of drug induced hepatitis during chemoprophylaxis (see text and British Thoracic Society1). (For recommendations about the prevention of TB in the small minority of patients with Crohn’s disease not taking concomitant immunosuppressive therapy, and in those with ulcerative colitis in whom infliximab is being considered, see British Thoracic Society1).

WHAT IS THE RISK OF TB?

In the general population in the UK, the incidence of TB depends on a range of factors which include age, ethnicity, and country of birth.8 The annual risk of TB in the UK is increased at least 30-fold in Black Africans aged over 15 years and in South Asians born outside the UK; it is even greater in people from other ethnic groups resident in the UK for less than five years.1

In Crohn’s disease which has not been treated with infliximab, the incidence of TB is unknown; indeed, in some patients it may of course be difficult, initially at least, to distinguish the one diagnosis from the other. Infliximab appears to increase the background risk of TB by approximately fivefold in both Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis,1 most, although not all, cases being extrapulmonary and occurring within the first three months of treatment.9–13 Although the incidence of infliximab related TB may now be falling due to improved risk assessment, chemoprophylaxis (see below), and/or reporting fatigue,11 complacency is clearly inappropriate: mortality of TB in the early days of its recognition in association with the use of infliximab approached 10%.

HOW CAN THE RISK OF TB BE MINIMISED IN PATIENTS TO BE GIVEN INFLIXIMAB (FIG 1 ▶)?

Recommendations from several sources, including the European Agency for Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) (see below), agree that patients in whom the use of anti-TNF therapy is being considered should be meticulously questioned about prior TB and its treatment, and have a chest x ray taken.1,12–16

Patients with a history of TB and/or abnormal chest x ray

Patients with a history of TB or an abnormal chest x ray should be referred directly to a specialist with expertise in TB.1 Those with active TB should receive standard antituberculous chemotherapy for at least two months before starting on infliximab. Patients with a chest x ray showing previous TB, or with a history of previous extrapulmonary TB which has been fully treated, should be carefully monitored during infliximab therapy; those in whom treatment may have been inadequate should have active TB excluded by appropriate investigation and should be started on chemoprophylaxis two months before starting infliximab.

Patients with no history of TB and normal chest x ray

Some guidelines have suggested that a tuberculin test should be used to direct the optimal approach in this group of patients.2,12,13 Recent data however have confirmed a very high incidence of anergy in patients with Crohn’s,14 and the EMEA recommendations specifically warn prescribers of the risk of false negative skin test results in severely ill or immunocompromised patients with Crohn’s disease15. Indeed, since under existing (2002) NICE guidelines16 all patients with Crohn’s disease in the UK needing infliximab will be chronically ill and currently or recently taking corticosteroids and/or immunomodulatory drugs, tuberculin testing will not assist in decision making and is considered unnecessary.1 (There are no data on the incidence of anergy to tuberculin in patients with ulcerative colitis; in these, currently exceptional patients, the guidelines described in full by the British Thoracic Society1 should be followed.)

What does need to be considered is the annual risk of TB in individual patients to be given infliximab: as indicated above, this is increased about fivefold by infliximab and still further in some ethnic groups. This risk needs to be balanced against the risk of side effects caused by TB chemoprophylaxis, which is dependent on the regimen to be used.1 The commonest regimen, isoniazid for six months, has a hepatitis risk rate of about 280/100 000 treated patients.1 Two shorter regimens, rifampicin with isoniazid for three months and rifampicin with pyrazinamide for two months, cause serious hepatitis much more often (1800 and 6600/100 000 treated patients, respectively).1

These considerations mean that, in general, Caucasians in the UK with no history of TB and a normal chest x ray need no TB chemoprophylaxis. In contrast, even if they have no TB history, and their chest x ray is normal, Black Africans aged over 15, South Asians born outside the UK, and other ethnic groups resident in the UK for less than five years have such a high risk of TB while on infliximab that they should usually be offered isoniazid for six months when starting it.1 In other non-Caucasian ethnic groups, data on the risk of TB are too limited for it to be possible to make definitive recommendations.

Monitoring for TB in patients on infliximab

All patients on infliximab should be monitored carefully for symptoms such as fever, weight loss, or cough: gastroenterologists should be alert to the possibility of extrapulmonary as well as the more familiar lung disease. The slightest suspicion of TB should prompt immediate referral to a specialist TB physician.

CONCLUSIONS

Tuberculosis is one of the most serious complications of the use of infliximab. In each patient in whom therapy with infliximab is being considered, a plan should be drawn up based on their history, chest x ray, ethnicity, place of birth, and duration of residence in the UK (see fig 1 ▶). Implementation of these recommendations is likely to reduce dramatically the risk of TB in patients given infliximab and other anti-TNF agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Professor P Ormerod (British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Com-mittee) and to members of the IBD Section (Chairman, Dr S Travis) and Clinical Services Committee (Chairman, Dr M Denyer) of the British Society of Gastroenterology for reviewing this paper and for their helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ormerod LP, Milburn HJ, Gillespie S, et al. BTS recommendations for assessing risk, and for managing M tuberculosis infection and disease in patients due to start anti-TNF alpha treatment. Thorax. Published Online First: 29 July 2005. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.046797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Rutgeerts P, van Assche G, Vermeire S. Optimizing anti-TNF treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2004;126:1593–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maini SR. Infliximab treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clinics N Am 2004;30:329–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun J, Sieper J. Biological therapies in the spondyloarthropathies—the current state. Rheumatology 2004;43:1072–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Olson A, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of infliximab therapy for active ulcerative colitis: Act 1 trial. Gastroenterology 2005;128:A105. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandborn WJ, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, et al. Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: the Act 2 trial. Gastroenterology 2005;128:A104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarnerot G, Hertevig E, Friis-Liby I - L, et al. Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis. A randomised placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology 2005;128:1805–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose AMC, Watson JM, Graham C, et al. Tuberculosis at the end of the 20th century in England and Wales: results of a national survey in 1998. Thorax 2001;56:173–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-alpha neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1098–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallis RS, Broder MS, Wong JY, et al. Granulomatous infectious diseases associated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:1261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez-Reino JJ, Carmona L, Valverde VR, BIOBADASER Group, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors may predispose to significant increase in tuberculosis risk: a multicenter active-surveillance report. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:2122–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardam MA, Keystone EC, Menzies R, et al. Anti-tumour necrosis factor agents and tuberculosis risk: mechanisms of action and clinical management. Lancet Inf Dis 2003;3:148–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a user’s guide for clinicians. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2962–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mow WS, Abreu-Martin MT, Papadakis KA, et al. High incidence of anergy in inflammatory bowel disease patients limits the usefulness of PPD screening before infliximab therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:309–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. European Agency for Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) Public Statement on Infliximab (Remicade): update on safety concerns (2002). http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/press/pus/003202.pdf (accessed 16 August 2005).

- 16.NICE. Guidance on the use of infliximab for Crohn’s disease. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, technology appraisal guidance, No 40, 2002, (also online at http://www.nice.org.uk/pdf/NiceCROHNS40GUIDANCE.pdf; accessed 16 August 2005 ).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.