Abstract

DNA synthesis in Escherichia coli is inhibited transiently after UV irradiation. Induced replisome reactivation or “replication restart” occurs shortly thereafter, allowing cells to complete replication of damaged genomes. At the present time, the molecular mechanism underlying replication restart is not understood. DNA polymerase II (pol II), encoded by the dinA (polB) gene, is induced as part of the global SOS response to DNA damage. Here we show that pol II plays a pivotal role in resuming DNA replication in cells exposed to UV irradiation. There is a 50-min delay in replication restart in mutant cells lacking pol II. Although replication restart appears normal in ΔumuDC strains containing pol II, the restart process is delayed for >90 min in cells lacking both pol II and UmuD′2C. Because of the presence of pol II, a transient replication-restart burst is observed in a “quick-stop” temperature-sensitive pol III mutant (dnaE486) at nonpermissive temperature. However, complete recovery of DNA synthesis requires the concerted action of both pol II and pol III. Our data demonstrate that pol II and UmuD′2C act in independent pathways of replication restart, thereby providing a phenotype for pol II in the repair of UV-damaged DNA.

DNA polymerase II (pol II), encoded by the damage-inducible dinA (polB) gene of Escherichia coli, is regulated at the transcriptional level by the LexA repressor (1–4) and is induced ≈7-fold from ≈50 to 350 molecules per damaged cell (4). Although pol II was discovered in 1970 (5) and was characterized biochemically shortly thereafter (6, 7), it has remained an enigma, in contrast to polymerases I and III, which carry out clearly defined roles in DNA repair and replication, respectively (8).

Genetic studies reveal that pol II may be involved in repairing DNA damaged by UV irradiation (9) or oxidation (10), in bypassing abasic lesions in vivo in the absence of heat shock induction (11) and in the repair of interstrand cross-links (12). It has been shown that pol II catalyzes episomal DNA synthesis in vivo (13, 14) and synthesizes chromosomal DNA in a pol III antimutator (dnaE915) background (14). Pol II is able to catalyze processive synthesis in vitro in the presence of β-sliding clamp and clamp-loading γ-complex, suggesting a role for pol II in replication and repair (15–17).

After UV irradiation, a replication fork may be become stalled when encountering a DNA template lesion (18). In this paper, we report that pol II plays a pivotal role in replication restart (19), i.e., induced replisome reactivation (20–22), a process whereby “reinitiation” of DNA synthesis on UV-damaged DNA allows lesion bypass to occur in an error-free repair pathway. Our data provide a well defined role for pol II in repairing UV-induced chromosomal DNA damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

The E. coli K-12 strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. To avoid complications arising from the use of nonisogenic strains, we moved the previously generated polB (10) and umuDC (23) null mutations into the commonly used K-12 laboratory strain, AB1157, by standard methods of P1 transduction (24). The presence of the Δ(araD-polB)∷Ω allele was selected on LB agar plates containing 20 μg/ml spectinomycin and was confirmed by PCR analysis (see below). Use of higher concentrations of spectinomycin were avoided because they resulted in colonies with different size morphology consistent with the acquisition of additional chromosomal mutations in rpsE (25). To simplify notation, we refer to the Δ(araD-polB)∷Ω allele as ΔpolB. The Δ(umuDC)595∷cat allele was selected on LB agar plates containing 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and its presence also was confirmed by PCR analysis (see below). Again, for simplicity, we refer to the Δ(umuDC)595∷cat allele as ΔumuDC. The temperature-sensitive dnaE486 allele was transduced into the appropriate background by selecting for the closely linked zae502∷Tn10 transposon (15 μg/ml tetracycline) and subsequently screening transductants for reduced/no growth at 43°C. LB and M9 minimal media were as described (24), with M9 Glucose (0.4%) media supplemented with thiamine (2 μg/ml), 0.1M MgSO4, and required amino acids (20 μg/ml), (M9G+ media). Antibiotic concentrations were as follows: spectinomycin (20 μg/ml), streptomycin (30 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml), and tetracycline (15 μg/ml).

Table 1.

E. coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotypes | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| SH2101 | Δ(araD-polB)∷Ω | (10) |

| RW82 | Δ(umuDC)595∷cat | (23) |

| CS115 | dnaE486, zae502∷Tn10 | I. Tessman (Purdue Univ.) |

| AB1157* | dnaE+, umuDC+, polB+ | S. Lovett (Brandeis Univ.) |

| STL1336 | Δ(araD-polB)∷Ω | P1.SH2101 × AB1157 |

| SR1157U | Δ(umuDC)595∷cat | P1.RW82 × AB1157 |

| SR1336U | Δ(araD-polB)∷Ω, Δ(umuDC)595∷cat | P1.RW82 × STL1336 |

| RW620 | dnaE486, zae502∷Tn10 | P1.CS115 × AB1157 |

| RW622 | Δ(araD-polB)∷Ω, dnaE486, zae502∷Tn10 | P1.CS115 × STL1336 |

Complete genotype: thi-1, thr-1, araD139, leuB6, lacY1, argE3(oc), Δ(gpt-proA)62, mtl-1, xyl-5 rpsL31, tsx-33, supE44, galk2(oc), hisG4(oc), kdgK51, rfbD1.

Colony PCR Assay to Test for ΔpolB and ΔumuDC Genotypes.

Although both Δ(araD-polB)∷Ω and Δ(umuDC)595∷cat null mutant alleles were constructed by using standard gene interruption techniques and can be simply selected directly by using the appropriate antibiotic resistance, the presence of each allele was confirmed by colony PCR. In both cases, primers were designed to anneal to the insert and flanking sequence. A PCR product is obtained, therefore, only if the insert is in its correct chromosomal location. The primers used to detect the Δ(araD-polB)∷Ω allele were 5′TCTGTCCTGGCTGGCGAACGA3′ (in the Ω fragment) and 5′CCGACGGGATCAATCAGAAAGGTG3′ (in polB) and resulted in an 817-bp PCR fragment. The primers used to detect the Δ(umuDC)595∷cat allele were 5′AGGCCACGTGAGCACAAGATAAGA3′ (in the upstream flanking region of the umu operon) and 5′ATAGGTACATTGAGCAACTGACTG3′ (in the cat gene) and resulted in a 530-bp PCR product. We also have verified the absence of pol II and UmuD′2C in the ΔpolB and ΔumuDC strains, respectively, by Western blotting using highly sensitive antibodies directed against pol II and UmuD′2C proteins.

UV Survival Assays.

Fresh overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 vol/vol in LB medium, were grown to an OD600 of ≈0.2–0.3 (≈2 × 108 cells/ml), were resuspended in equal volume of cold 0.85% NaCl or 10 mM MgSO4, and were UV-irradiated in 10-ml aliquots in glass Petri dishes [254 nm; UV fluence was measured by using a Model 65A UV Radiometer (Yellow Springs Instruments)]. Dilutions were plated on LB agar plates, and the surviving fraction was determined after 24-h incubation at 37°C. The UV survival assays were repeated five times and were highly reproducible.

Measurement of DNA Synthesis at 37°C.

The rate of DNA synthesis was measured as described (20, 21). Aliquots (500 μl) were taken from exponentially growing cultures at 37°C (in M9G+ media) and were pulse-labeled for 2 min with 3[H] thymidine (15 μCi/ml; specific activity ≈70 Ci/mM) at various times before and after UV irradiation (30 J/m2; at A450 of ≈0.08). Pulses were terminated by addition of ice-cold 10% trichloroacetic acid, and precipitated counts of 3[H] incorporated (on Whatman GF/A filters washed twice with cold 5% trichloroacetic acid and 95% ethanol) were determined by scintillation counting. Values were plotted as percent relative to the cpm at the time of UV irradiation; typical minimum cpm were ≈5 × 103. At the time of each pulse-labeling, A450 also was determined. Each experiment was repeated six times and was highly reproducible.

Measurement of DNA Synthesis in Temperature-Sensitive Strains.

Cultures were grown exponentially at 30°C (to A450 of ≈0.08) and either were UV irradiated, as described above, or were not irradiated. Half of the UV-irradiated cultures and half of the nonirradiated cultures were grown at 30°C whereas the other half of each was shifted to 43°C. Pulse-labeling was carried out as described above, but at 30°C and 43°C, respectively. Each experiment using the temperature-sensitive pol III strain was repeated four times and was highly reproducible.

RESULTS

The rate of DNA synthesis declines significantly after exposure of wild-type E. coli to UV light, but then resumes at a normal rate within a period of ≈10–15 min by a process referred to as induced replisome reactivation (20, 21), also known as replication restart (19). In this paper, we have used a combination of ΔpolB (dinA), ΔumuDC, and dnaE486(ts) mutant strains to investigate cell survival and the kinetics of [3H]TdR incorporation into DNA after UV radiation.

Decreased UV Survival of a ΔpolB ΔumuDC Strain.

Nearly 30 genes, including polB and umuDC, are currently known to be transcriptionally regulated by LexA. Many of these genes encode proteins involved in some aspect of DNA repair and damage tolerance. However, when one compares isogenic polB+ and ΔpolB strains, there is no discernible difference in their ability to survive the lethal effects of exposure to UV light (Fig. 1). By comparison, an isogenic ΔumuDC strain, devoid of the well characterized damage tolerance mechanism of translesion DNA synthesis, is moderately UV-sensitive (Fig. 1). Although the ΔpolB allele has no apparent effect on an otherwise wild-type cell, the ΔpolB ΔumuDC strain is ≈2- to 3-fold more UV-sensitive than the isogenic polB+ΔumuDC strain (Fig. 1), suggesting that pol II may, in fact, play a role in DNA repair.

Figure 1.

UV survival of ΔpolB and ΔumuDC strains. ●, AB1157 (polB+umuDC+); ○, STL1336 (ΔpolB); ▾, SR1157U (ΔumuDC); ▿, SR1336U (ΔpolBΔumuDC). The data represent the mean of three experiments. Error bars show the standard error of the mean.

Recovery of DNA Synthesis After Exposure to UV Irradiation.

As a damage-inducible DNA polymerase, it seemed reasonable to expect that the hitherto undefined role for pol II in DNA damage tolerance would be related to some form of post-UV irradiation DNA synthesis within the cell. A clue as to what this function might be came from the synergy observed between the ΔpolB and ΔumuDC alleles reminiscent of that seen with recA718 in combination with various umuDC alleles (21, 26), which together are unable to resume replication after UV irradiation (21). It should be stressed that the UV sensitivity of the uvr+ ΔpolB ΔumuDC strain was clearly not as great as that observed in the uvr- recA718 umu strain (21). However, although UV survival curves of mutant E. coli strains often provide clues to the essential role of proteins in repair pathways, they are less informative on the kinetics of the repair pathway because the end-point of the assay is colony-forming ability, usually 24 h after UV irradiation. This may be especially true for pol II, where its role in DNA damage tolerance was not discovered because of the presence of back-up repair pathways.

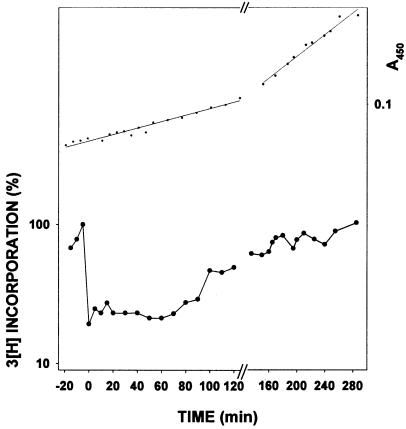

To follow the kinetics of replication restart, DNA synthesis rates were measured by assaying incorporation of 3[H]thymidine administered in short (2 min) pulses. DNA synthesis is inhibited transiently in wild-type cells immediately after UV irradiation (Fig. 2), as reported previously (20, 21). After a brief period of time (≈10 min), the rate of [3H] incorporation increases in wild-type cells, indicating the resumption of DNA synthesis. In an otherwise wild-type background, deletion of the umu operon has but a slight effect on the ability of the cell to perform replication restart (21) (Fig. 2A). The modest UV sensitivity of ΔumuDC strains can therefore be attributed most likely to their inability to perform translesion DNA synthesis, rather than to a global defect in DNA replication.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the rates of post-UV DNA synthesis in wild-type, ΔpolB, and ΔumuDC strains. Experiments were performed as described in Materials and Methods. In the lower portion, the rate of 3H thymidine incorporation (both before and after UV) is plotted on a logarithmic scale as a percentage of the rate of incorporation at the time of UV irradiation. In the upper portion, the linear regressions are determined from an average of A450 values for the two strains in each plot. (A) ○, AB1157 (polB+umuDC+); ■, SR1157U (ΔumuDC). (B) ○, AB1157 (polB+umuDC+); ▾, STL1336 (ΔpolB). The experiment from which the data were plotted was repeated six times and is reproducible. The delay before resumption of replication in the ΔpolB strain, shown in B, is occurring between 50 and 60 min post-irradiation.

In contrast, however, despite having no detectable effect on the overall UV survival of the strain, deletion of polB results in a cell that is clearly impaired in its ability to carry out normal replication restart. For example, at a UV dose of ≈30 J/m2, wild-type cells exhibit increased DNA synthesis rates as early as ≈10 min after irradiation with UV light whereas ΔpolB mutants require ≈50 min for resumption of normal synthesis rates (Fig. 2B). Although kinetically delayed, rates of DNA synthesis in the ΔpolB strain eventually match that of the wild-type cell. Such observations explain why there is no obvious effect of the ΔpolB allele on the ultimate ability of the cell to form colonies on the agar plates, some 24 h post-UV irradiation. These findings suggest that pol II plays a pivotal role in the ability of the cell to perform normal replication restart. The fact that cells do, however, eventually recover normal synthesis also suggests that they possess alternate pathways that can substitute for pol II, to restore replication.

We suggest that it is no coincidence that the time required for recovery of DNA synthesis rates in ΔpolB cells corresponds closely with the appearance of UmuD′ formed by the RecA-mediated cleavage of UmuD, which peaks at ≈45 min post-UV (27). Although the Umu proteins are not normally required for replication restart in wild-type cells, the 50-min delay in DNA synthesis in ΔpolB cells is clearly Umu-dependent (Fig. 3), suggesting that recovery in the ΔpolB strain may be caused by UmuD′2C-dependent lesion bypass rather than by reinitiation of synthesis downstream from a template lesion. In the ΔpolBΔumuDC double mutant, there appears to be no recovery of DNA synthesis 90 min post-UV (Fig. 3). However, DNA synthesis finally begins to recover in the double mutant at ≈100–110 min post-irradiation, implying the presence of yet another alternative replication restart pathway. The fact that the ΔpolBΔumuDC strain is more sensitive than the ΔumuDC strain suggests that not all UV-irradiated cells can use this backup pathway. The molecular basis of this third pathway is presently unknown, but, because the cells used in this study are rec+ and uvr+, it is reasonable to speculate that it involves some form of recombination and/or excision repair.

Figure 3.

Rates of post-UV DNA synthesis in strains deleted for both pol II and UmuDC. Replication restart DNA synthesis rates were measured as described in Materials and Methods using SR1336U (ΔpolBΔumuDC). The data were plotted as described in Fig. 2. The experiment from which the data were plotted was repeated four times.

DNA Synthesis in a Pol III Temperature-Sensitive Background.

Our finding that ΔpolB cells ultimately attain normal rates of DNA synthesis indicates that another polymerase can substitute for pol II. Although it is conceivable that such activity could be directly attributed to a UmuD′2C-associated polymerase activity (28), it seems far more likely that resumption of DNA synthesis in the absence of pol II depends on the cell’s main replicative enzyme, pol III. To investigate the respective roles of pol II and pol III in replication restart, we measured DNA synthesis in UV-irradiated cells containing the pol III temperature sensitive “rapid-stop” allele dnaE486.

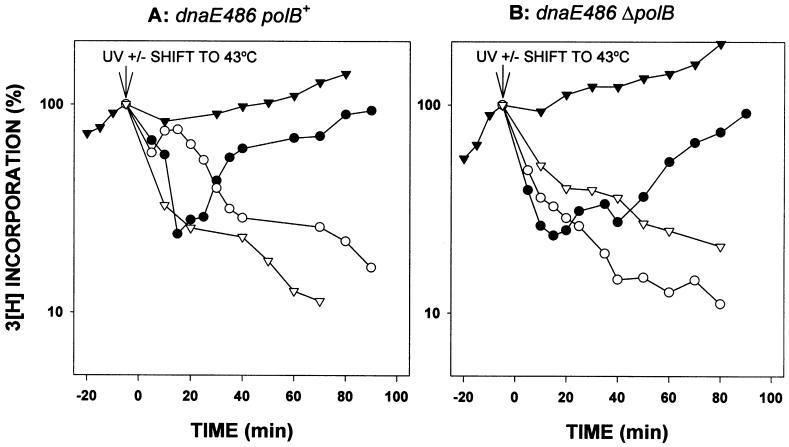

At the permissive temperature (30°C), DNA synthesis rates continue to increase in nonirradiated, exponentially growing dnaE486 cells, either in the presence or absence of pol II (Fig. 4 A and B). However, immediately after shifting the nonirradiated dnaE486 cells to the nonpermissive temperature (43°C), the rates of DNA synthesis diminish (Fig. 4), consistent with previous observations that the dnaE486 allele ceases DNA synthesis immediately at high temperature (29, 30).

Figure 4.

Rates of DNA synthesis in dnaE486 polB+/ΔpolB strains. The ability of cells to replicate their DNA was measured essentially as described in Fig. 2. The only difference is that the initial DNA synthesis was at 30°C. Where noted, some cells were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature of 43°C. (A) RW620 (dnaE486polB+) unirradiated at 30°C (▾); irradiated at 30°C (●); unirradiated at 43°C (▿); and irradiated at 43°C (○). (B) RW622 (dnaE486ΔpolB) unirradiated at 30°C (▾); irradiated at 30°C (●); unirradiated at 43°C (▿); and irradiated at 43°C (○). The experiment from which the data were plotted was repeated four times and is reproducible. The rapid resumption of replication followed by the steep decline in incorporation observed at nonpermissive temperature in the dnaE486polB+ strain, shown in A, was observed in each of the repeat experiments.

The pattern of DNA synthesis in the dnaE486 cells after UV irradiation (Fig. 4), when grown at the permissive temperature (30°C), is similar to that of the dnaE+ cells at 37°C with about a 50-min delay in the recovery for ΔpolB cells compared with a faster recovery in polB+ cells (Fig. 2). However, when UV-irradiated cultures are shifted to the nonpermissive temperature in dnaE486 cells that have a functional pol II present (Fig. 4A), the rates of DNA synthesis are initially high, indicating that replication restart has begun, but then drop after a short period of time (Fig. 4A). When the cultures that had been shifted to 43°C were restored to 30°C after 15 min, the DNA synthesis rates began increasing within ≈10 min in the dnaE486 polB+ strain but were delayed in the dnaE486 ΔpolB strain, with the rates again increasing at ≈50 min, in agreement with the behavior of the polB single mutant (data not shown). We interpret these results to indicate that pol II is involved in initiating replication restart but that it then is replaced by pol III. In support of this hypothesis, no recovery of DNA synthesis was observed in the UV-irradiated ΔpolB dnaE486 strain at the nonpermissive temperature (Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

Unlike E. coli DNA polymerases I and III, which have clearly defined roles in DNA repair and replication (8), the cellular role of E. coli pol II has remained an enigma since its discovery nearly 30 years ago (5). Pol II is induced 7-fold as part of the damage-induced LexA regulon (1–3), implying a role for this enzyme in copying damaged DNA templates. When compared with a wild-type strain, however, a ΔpolB strain apparently exhibits no gross defect in its ability to survive the lethal effects of UV irradiation (Fig. 1).

When one assays the ability of the Δ polB strain to recover DNA synthesis post-UV irradiation, we observe a significant delay in the resumption of DNA synthesis (Fig. 2). Further analysis reveals that post-UV DNA synthesis in a ΔpolB strain depends on UmuD′2C (Fig. 2) and that both the pol II-dependent and UmuD′2C-dependent pathways of replication restart also require DNA polymerase III. However, even in the absence of pol II and UmuD′2C, replication restart occurs some 90–100 min post-UV. These data suggest that the cell has at least three genetically separable pathway of replication restart at its disposal, to avoid the deleterious consequences of DNA damage.

A Pivotal Role for DNA Polymerase II in Replication Restart.

The necessity for replicating damaged templates becomes evident when one recognizes that just a single nonrepaired UV lesion may prove lethal to the cell by blocking pol III-catalyzed replication (18, 31). However, after inhibition of replication caused by DNA damage, the resumption of DNA synthesis in wild-type cells occurs rapidly, within ≈10 min after exposure to UV light (20) (Fig. 2). Our finding that replication restart is delayed by ≈50 min in a ΔpolB mutant suggests an early and pivotal role for pol II in the ability of wild-type cells to perform normal replication restart.

Although pol II is negatively regulated by LexA at the transcriptional level (1–3), the LexA-binding site in the polB operator is one of the weakest in the LexA regulon. As a consequence, the basal level of expression, ≈50 molecules per cell (4), is relatively high (2- to 3-fold greater than pol III). Furthermore, given the relatively weak affinity of LexA for the polB operator, pol II is likely to be induced (up to 7-fold) early on in the cell’s SOS response to DNA damage. The presence of high basal levels of pol II and its early induction might explain why replication restart occurs so rapidly after DNA damage. The pol II-dependent repair pathway does not involve the direct replication of damaged DNA and, given the high fidelity of pol II, is almost certainly error-free.

In vitro studies demonstrate that pol II interacts with pol III accessory proteins, β-clamp and γ-clamp-loading complex, to carry out highly processive DNA synthesis in vitro (15–17). However, at present, we do not know whether replication restart is facilitated solely by the catalytic subunit of pol II or by a putative pol II holoenzyme (HE) (pol II/β-γ complexes). If the latter is true, it does not appear that the pol II HE is able to complete duplication of the entire genome. Pol II clearly possesses the ability to begin the process, as shown by an initial burst of DNA synthesis at nonpermissive temperature in dnaE486 strains (Fig. 4A).

However, our finding that the rate of synthesis drops after an initial period of 10–15 min in the temperature-sensitive pol III strain at a nonpermissive temperature suggests that, under normal conditions, a switch takes place from pol II to pol III to complete replication of the genome. This switch occurs several minutes after exposure to UV light and probably happens after other DNA repair processes such as nucleotide excision repair have removed the majority of pol III-blocking lesions.

Genetic Requirements for Replication Restart in E. coli.

In the absence of pol II, replication restart is delayed considerably and apparently requires UmuD′2C (Fig. 2B). The UmuD′2C proteins are best characterized for their role in error-prone translesion DNA synthesis (28, 32–34), so it is not unreasonable to assume that, by performing this function, they circumvent the block to pol III HE-dependent replication imposed by the UV lesion. Indeed, it has been shown recently that UmuD′2C is a bona fide “error-prone” DNA polymerase, not requiring the presence of pol III core to bypass an abasic lesion (28, 35).

The 50-min delay in replication occurring when pol II is absent coincides with RecA-mediated conversion of UmuD to UmuD′ in UV-irradiated cells (27), suggesting that UmuD′C proteins may be involved in reinitiation of DNA synthesis on damaged templates. We speculate that the synthesis observed 50 min post-UV irradiation in ΔpolB cells (Fig. 2B) is caused primarily by the UmuD′2C catalyzed error-prone lesion bypass as opposed to “bona fide” error-free replication restart. The requirement for UmuD′2C to facilitate replication restart in the ΔpolB strain is the second such report of a role for UmuD′2C in replication restart. The first was in a recA718 background (21). Both studies clearly demonstrate that UmuD′2C plays an important role in replication restart under certain conditions. However, in an otherwise wild-type cell, it is unlikely that they play a major role because replication restart appears normal in their complete absence (20, 21) (Fig. 2A).

In the absence of the pol II- and UmuD′2C-dependent replication restart pathways in otherwise wild-type cells, replication resumes some 90 min post-UV irradiation, indicating yet another backup pathway allowing the cell to replicate its damaged DNA. The strains used in these studies are wild-type for all known repair functions, and previous genetic studies have implicated RecA (20, 21), RecF (36, 37), and the UvrABCD excison repair proteins (37) in replication restart. At the present time, however, it is not known in which of the aforementioned pathways any or all of these repair proteins function. Indeed, it is difficult to determine whether they are normally required or if they are required only under special conditions, as is the case with UmuD′2C, in the ΔpolB strain.

Roles of pol II, pol III, and UmuD′2C in Replication Restart in Wild-Type Cells.

The data presented here derived from a combination of ΔpolB, ΔumuDC, and dnaE486(ts) single and double mutant strains allow us to begin formulating a picture for the participation of pol II, pol III, and UmuD′2C in replication restart. Our studies suggest that, in a wild-type cell, replication restart can occur via at least three genetically separable pathways. Although it is conceivable that all three pathways operate simultaneously, the kinetics of replication restart observed in the various mutant strains used in this study suggest that they are temporally spaced such that two of the three pathways are only used should the first fail.

In a wild-type cell, replication restart occurs ≈10 min post-UV irradiation. However, replication restart is considerably delayed in cells lacking pol II, occurring some 50 min post-UV. This observation alone implicates a pivotal role for pol II in normal replication restart. Our experiment using a temperature-sensitive dnaE486 allele at nonpermissive temperature suggests that pol II initiates replication restart but is subsequently replaced by the cell’s main replicative enzyme, pol III.

It seems reasonable to speculate that pol II plays an important role in catalyzing replication restart in either one or two ways. In a first “copy choice” pathway, as proposed by H. Echols and colleagues (38, 39), a RecA filament downstream from a blocked pol III HE may associate with a replication complex from the undamaged complementary strand, forming a transient triple-stranded structure. Pol II then could bypass a lesion by copying the undamaged daughter strand, then switching back once the lesion has been bypassed, with pol III HE then taking over from pol II to continue replication. In a second “gap creating” pathway, pol II might restart replication at a template site distal from a stalled replication fork, thereby leaving a gap downstream of the lesion that is later repaired by recombination and excison repair pathways (31, 40).

In the absence of pol II, the cell apparently uses the ability of UmuD′2C to replicate across the normally replication-blocking lesion, to allow complete duplication of the genome by pol III. It does not appear that UmuD′2C is normally used in a wild-type cell because, in its absence, the kinetics of replication restart is essentially unchanged. Of course, that does not rule out that, under special conditions, such as severe DNA damage or in certain genetic backgrounds, such as a recA730 lexA(Def) strain in which the intracellular level of UmuD′2C is elevated, the Umu complex could compete for the same 3′ primer terminus as pol II. Indeed, compared with the 50-min delay in replication restart observed in the ΔpolB recA+ lexA+ strain, there is virtually no delay in a ΔpolB recA730 lexA(Def) strain (data not shown), presumably because of the overabundance of UmuD′2C. Thus, in a polB+ recA730 lexA(Def) strain, replication restart is likely to result from a combination of both the pol II and UmuD′2C-dependent pathways.

The third pathway of replication restart is the least understood and needs to be better characterized at the genetic level. It appears to be used some 90–100 min post-UV and presumably only occurs under special conditions in which the pol II and UmuD′2C pathways have failed.

In this paper, we have shown that pol II is pivotally involved in the initiation of replication-restart. This is a well defined chromosomal function demonstrated for this enigmatic polymerase, which resembles eukaryotic α-polymerases (2) much more closely than either of its prokaryotic counterparts, pol I and pol III. Because pol II is unable to initiate synthesis in the absence of a primer, it seems likely that a primosome complex also may be required, although a template strand switching mechanism also could provide a means for error-free lesion bypass (31, 41). It is also likely that recombination proteins such as RecA, RecF, RecO, and RecR play an important role in this process (36, 37). Although much work remains to be done in establishing the biochemical mechanism, an important role for pol II during initiation of replication restart now has been established.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM42554.

ABBREVIATIONS

- pol II

Escherichia coli DNA polymerase II

- HE

holoenzyme

References

- 1.Bonner C A, Randall S K, Rayssiguier C, Radman M, Eritja R, Kaplan B E, McEntee K, Goodman M F. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18946–18952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner C A, Hays S, McEntee K, Goodman M F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7663–7667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwasaki H, Nakata A, Walker G, Shinagawa H. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6268–6273. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6268-6273.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu Z, Goodman M F. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8611–8617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knippers R. Nature (London) 1970;228:1050–1053. doi: 10.1038/2281050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wickner R B, Ginsberg B, Berkower I, Hurwitz J. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:489–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wickner R B, Ginsberg B, Hurwitz J. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornberg A, Baker T A. DNA Replication. New York: Freeman; 1992. pp. 113–182. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masker W, Hanawalt P, Shizuya H. Nat New Biol. 1973;244:242–243. doi: 10.1038/newbio244242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escarcellar M, Hicks J, Gudmundsson G, Trump G, Touati D, Lovett S, Foster P, McEntee K, Goodman M F. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6221–6228. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6221-6228.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tessman I, Kennedy M A. Genetics. 1993;136:439–448. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berardini M, Foster P L, Loechler E L. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2878–2882. doi: 10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t031385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster P L, Gudmundsson G, Trimarchi J M, Cai H, Goodman M F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7951–7955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rangarajan S, Gudmundsson G, Qiu Z, Foster P L, Goodman M F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:946–951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wickner S, Hurwitz J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:4120–4124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes A J, Bryan S K, Chen H, Moses R E, McHenry C S. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4568–4573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonner C A, Stukenberg P T, Rajagopalan M, Eritja R, O’Donnell M, McEntee K, Echols H, Goodman M F. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11431–11438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence C W, Borden A, Banerjee S K, LeClerc J E. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2153–2157. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Echols H, Goodman M F. Mutat Res. 1990;236:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(90)90013-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khidhir A M, Casaregola S, Holland I B. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;199:133–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00327522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witkin E M, Maniscalco R V, Sweasy J B, McCall J O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6805–6809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sweasy J B, Witkin E M. Biochimie. 1991;73:437–448. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90111-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodgate R. Mutat Res. 1992;281:221–225. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(92)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller J H. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics: A Laboratory Manual and Handbook for Escherichia coli and Related Bacteria. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill S A, Little J W. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5913–5915. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5913-5915.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho C, Kulaeva O I, Levine A S, Woodgate R. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5411–5419. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5411-5419.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sommer S, Boudsocq F, Devoret R, Bailone A. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:281–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang M, Bruck I, Eritja R, Turner J, Frank E G, Woodgate R, O’Donnell M, Goodman M F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9755–9760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wechsler J A, Gross J D. Mol Gen Genet. 1971;113:273–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00339547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharif F, Bridges B A. Mutagenesis. 1990;5:31–34. doi: 10.1093/mutage/5.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rupp W D, Howard-Flanders P. J Mol Biol. 1968;31:291–304. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato T, Shinoura Y. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;156:121–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00283484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinborn G. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;165:87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00270380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reuven N B, Tomer G, Livneh Z. Mol Cell. 1998;2:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang, M., Shen, X., Frank, E. G., O’Donnell, M., Woodgate, R. & Goodman, M. F. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA96, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Courcelle J, Carswell-Crumpton C, Hanawalt P C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3714–3719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Courcelle J, Crowley D J, Hanawalt P C. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:916–922. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.916-922.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Echols H. Biochimie. 1982;64:571–575. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(82)80089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodgate R, Rajagopalan M, Lu C, Echols H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7301–7305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rupp W D, Wilde C E, Reno D L, Howard-Flanders P. J Mol Biol. 1971;61:25–44. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgins N P, Kato K, Strauss B. J Mol Biol. 1976;101:417–425. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]