Abstract

An athymic mouse-derived immature T-cell clone, N-9F, was not maintained by interleukin-2 alone but required another soluble factor, contained in concanavalin A-stimulated rat splenocyte culture supernatant, namely T cell growth factor (TCGF), for its proliferation. An N-9F-proliferation factor (NPF) was isolated in a pure form from TCGF. N-9F cells and immature thymocytes proliferated in the presence of NPF at 10−11−10−8 g/ml in a dose-dependent manner, but adult thymocytes were not stimulated by NPF. NPF increased DNA synthesis of N-9F. NPF increased CD4 and CD8 double negative thymocytes and CD8 single positive thymocytes in fetal thymus organ culture. A hamster anti-NPF antiserum possessing the capacity to neutralize N-9F proliferation activity of NPF decreased double negative thymocytes. The amino-terminal amino acid sequence of NPF was identified to be Ser-Leu-Pro-Cys-Asp-Ile-Cys-Lys-Thr-Val-Val-Thr-Glu-Ala-Cys-Asn-Leu-Leu-Lys-Asp- and was identical to that of rat saposin A. The apparent molecular weight of NPF, 16 000, was comparable to that of saposin A. A rabbit anti-mouse recombinant His-tag (mrH)-saposin A antibody recognized a 16 000 MW molecule in TCGF. A Hitrap-saposin A antibody column bound NPF and pulled down the NPF activity in TCGF. Thus, NPF in TCGF was a saposin A-like protein possessing the capacity for growth and differentiation of immature thymocytes.

Introduction

Although the role of the thymic microenvironment in both proliferation and maturation of T lymphocytes has been of increasing interest, the mechanisms of thymic stromal cell (TSC) T-cell interaction are largely unknown.1–7 In order to investigate the role of TSC on T-cell growth and development, we previously established a TSC-reactive CD4+ 8+ T-cell clone, N-9F, derived from an athymic mouse spleen.8 It expressed both full length γ and δ T-cell receptor mRNA. By culturing N-9F on TSC, [3H]thymidine incorporation was retained and expression of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor was induced. The phenomena were also observed on TSC from H-2 allogenic mice, but not on other cell types such as splenic adherent cells or fibroblasts. After addition of recombinant IL-2 into the N-9F culture with TSC, N-9F showed enhanced IL-2 receptor expression and proliferated greatly.

N-9F was not maintained by IL-2 alone but required another soluble factor, contained in concanavalin A-stimulated rat or mouse splenocyte culture supernatant, namely T-cell growth factor (TCGF), for its proliferation.8 So far as we have tested, N-9F did not proliferate with any single human and mouse recombinant (r) lymphokines (hrIL-1, hrIL-2, mrIL-4, hrIL-6, mrIL-7, and mr-interferon-γ) and chemokines (mrIL-8 and hr stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1β) without TSC. In this report, we describe isolation of a soluble proliferation factor of N-9F (NPF) in TCGF.

Materials and methods

Cells

The T-cell clone, N-9F was established as previously described.8 Briefly, spleen cells from BALB/c nu/nu mice were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 20% TCGF and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Filton PTY. Ltd, Victoria, Australia), 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 10−5 m 2-mercaptoethanol and 100 µg/ml kanamycin. A TCGF-dependent T-cell clone, N-9F, showed significant proliferation on TSC, as described previously.8

Thymocytes from day 17 (E17) BALB/c fetuses (Japan SLC Inc., Shizuoka) and the thymocytes and splenocytes from BALB/c adult mice were prepared according to routine procedures.

Cell proliferation assay

The procedures for the N-9F proliferation assay were essentially those previously described.8 N-9F (2·5 × 104 cells/well) washed with TCGF-free RPMI-1640 medium were precultured in 50 µl medium for 2 hr and were added to the sample in 50 µl medium. Thirty-six hr later, proliferation of N-9F was measured by a 3,(4.5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) method.9 Separately, cells were cultured for 24 hr and pulsed for 24 hr with [3H]thymidine. The amount of radioactivity incorporated was measured. The thymocyte and splenocyte proliferation assay was performed in essentially the same manner, except using serum-free RPMI-1640 medium.

N-9F (1·0 × 105 cells/well) were cultured with sample in 200 µl RPMI-1640 medium or serum-free RPMI-1640 medium. Forty-eight hr later, cell number was counted by a trypan blue assay, and cells were fixed with 70% ethanol, treated with RNase and stained with propidium iodide. The DNA content of cells was determined with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer, Cell Quest software and ModFit software (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA).

Fetal thymus organ culture (FTOC)

FTOC was performed according to the method of Kisielow et al.10 Briefly, five thymus lobes from day 14 (E14) BALB/c fetuses were cultured on nitrocellulose membranes (Corning, New York, NY) and immersed in RPMI-1640 medium containing sample for 4 or 6 days. Cells in thymus lobes and on membrane were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD4 (clone YTS191.1, L3/T4-RD1, Coulter Immunology, Hialeah, FL) and fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD8 (clone YTS169.4, Ly-2-FITC). Flow cytometric studies were performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and Cell Quest software.

Fractionation of TCGF

Abundantly available rat spleens were used as a source of TCGF. Twenty l of TCGF were generated by culturing splenocytes of 400 male Wistar rats (12 weeks old, Japan SLC Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) with 5 µg/ml concanavalin A in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium for 40 hr. They were then concentrated 10-fold with a MiniPlateTM-3 (3000, molecular weight cutoff, Amicon Inc. Beverly, MA). An aliquot of the crude concentrates was adjusted to pH 2·5 with 1 n HCl and applied on a Sep-Pak Plus C18 cartridge (Waters Co., Milford, MA) in 40 separate runs. The cartridge was washed with 40% acetonitrile (AcCN) in 0·05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and the active fraction was eluted with 53% AcCN in 0·05% TFA. The 53% AcCN fractions pooled from the crude concentrates were concentrated by an evaporator under vacuum and applied to an Asahipak GS320 column (7·6 × 500 mm, Asahi Chemical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) equilibrated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). High pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed with a Waters 600E Multisolvent Delivery System equipped with a Waters 484 Tunable Absorbance Detector and Waters 741 Data Module (Japan Waters, Tokyo). The GS320 column was eluted with PBS at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and the eluate was monitored by the absorbance at 280 nm. A GS320 active fraction was adjusted to pH 2·5 and applied to a Cosmosil 5C18-AR column (4·6 × 150 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Osaka, Japan). The C18 HPLC was done using a linear gradient elution with 43% 2-propanol (2-PrOH)/AcCN (7 : 3) in 0·05% TFA and 53% 2-PrOH/AcCN (7 : 3) in 0·05% TFA for 40 min at a flow rate of 0·5 ml/min, and the eluate was monitored by absorbance at 210 nm. A C18 active fraction was concentrated into dryness with an evaporator under vacuum, to give N-9F-proliferation factor (NPF).

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE)

SDS–PAGE was performed on a 17% polyacrylamide gel as described by Laemmli.11 Proteins were visualized by a silver-staining method, a Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 method according to the manufacturer's instructions, or a Western blotting procedure.

Amino acid sequencing

The sequencing was performed with a Protein Sequencer (Model 491, Applied Biosystems Japan, Tokyo).

Expression of mouse recombinant saposin A in Escherichia coli

The procedures were essentially those described by Qi et al.12 The oligonucleotide primers were: forward, 5′-TAAAGGATCCTCCCTTCCTTGCGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCTCGAATTCTACTCCTGAAGGGA-3′; they were synthesized by BEX Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). DNA sequencing was performed with a Sequence ABIPRIZM™ 310 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin Elmer Japan, PE Applied Biosystems, Chiba, Japan). The saposin A coding region was generated from the prosaposin cDNA (pGEM-4Z-mouse prosaposin, a gift of Dr M. Tsuda) as a template using specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers. PCR was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin Elmer, Takara Biochemicals, Tokyo, Japan), and the reactions contained 1·25 unit AmpliTaq Gold polymerase, 4 ng plasmid containing prosaposin cDNA, 0·2 µm oligonucleotide primers, 1·5 mm MgCl2, 0·2 mm deoxynucleotides, and AmpliTaq Gold enzyme buffer, pH 8·3, in a final volume of 25 µl. Reactions were cycled 40 times through the melting, annealing, and extension temperatures of 94, 60, and 72°, respectively, for 1–2 min each. The PCR products were purified with a DNA purification kit (Japan Bio-Rad Laboratory, Tokyo) and digested at 37° for 2 hr with the appropriate restriction endonucleases. The digested DNA fragments were purified and ligated into the appropriate sites of the expression vector pET28-a(+) to produce the expression plasmid. After transformation of E. coli strain DH5α cells, positive clones were screened by PCR analysis, and inserts were completely sequenced to ensure fidelity. For expression, the pET construct was used to transform E. coli BL21 (-SI) cells, which have the NaCl-inducible T7 polymerase gene. Transformants were grown at 37° in 500 ml of NaCl-free LB medium containing 30 µg/ml kanamycin to OD600 = 0·5. NaCl was added to a final concentration of 0·2 mm. The cells containing the saposin A construct was reincubated at 37° for 2 hr and harvested by centrifugation (2000 g, 10 min). Harvested cells were resuspended in 10 ml of 1% Triton-X-100 in PBS and lysed by ultrasonic irradiation (Sonicator, Heat System-Ultrasonics Inc., New York, NY) in a cup horn with five 30-s bursts at output control 3. The lysates were clarified at 15 000 g for 15 min The supernatants were fractionated by a nickel-charged His Bind resin column according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein fraction eluted from the column was analysed by SDS–PAGE. The obtained mouse recombinant His-tag (mrH)-saposin A gave an apparent band at 12·5 kDa using Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining in SDS–PAGE (data not shown).

Antibodies against mrH-saposin A and rat NPF

A rabbit anti-mrH-saposin A antiserum was produced by immunizing intraperitoneally (i.p.) rmH-saposin A (1 mg) emulsified with Freund's complete adjuvant twice and rmH-saposin A (1 mg) emulsified with Freund's incomplete adjuvant, and purified by successive chromatographies on a Protein G column and a Hitrap-mrH-saposin A column (Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan) prepared according to the manufacture's instructions. A rabbit anti-ovalbumin antiserum was produced in the same way as a rabbit anti-mrH-saposin A antiserum, and purified by chromatography on a Protein G column. Separately, an Armenian hamster anti-rat NPF antiserum was produced by immunizing i.p. rat NPF (150 ng) adsorbed on aluminium hydroxide gel twice and rat NPF (300 ng) emulsified with Freund's incomplete adjuvant. A Western blotting study was conducted according to routine procedures using anti-mrH-saposin A antibody as the first antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit as the second antibody. An affinity chromatography of serum-free TCGF (100 µl) on a Hitrap-mrH-saposin A antibody column (1 ml) was performed using PBS as a start buffer and 0·1 m Gly-HCl buffer (pH 2·7) as an elution buffer, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The fractions bound and unbound to the column were dialysed, lyophilized and dissolved in 100 µl of RPMI-1640 medium. The fraction unbound to the column was repeatedly applied to the affinity chromatography. A part of the bound fraction was analysed by octadecyl silica (ODS)-HPLC.

Results

Purification of NPF

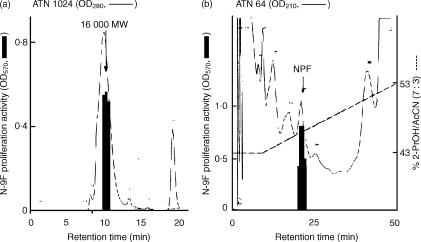

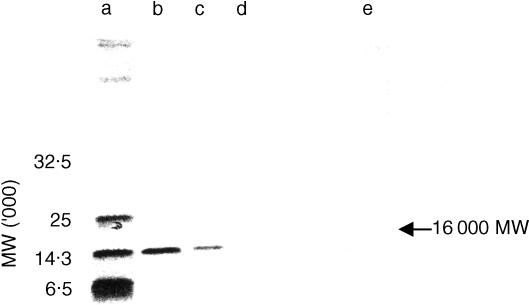

An active factor for N-9F proliferation in TCGF was purified by successive chromatographies on Sep-pak C18, Asahipak GS320 and Cosmosil C18 (Fig. 1). The homogeneity was confirmed by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 2). The yield was approximately 2 µg from 20 l of TCGF containing 20 g protein.

Figure 1.

Purification of NPF. (a) Asahipak GS-320 HPLC of active Sep-pak C18 fraction using PBS as a solvent. (b) Cosmosil C18 HPLC of active Asahipak GS-320 fraction. The elution was done with a linear gradient of increasing concentrations of 2-PrOH/AcCN (7 : 3) in 0·05% TFA. An aliquot of each fraction was subjected to the proliferation assay of N-9F by an MTT method.

Figure 2.

SDS–PAGE of NPF. NPF was subjected to electrophoresis on a 17% gel and detected by silver staining. (a) Protein MW standard; lysozyme (50 ng) (b), (25 ng) (c), (12·5 ng) (d); and (e) NPF.

Biological activity of NPF

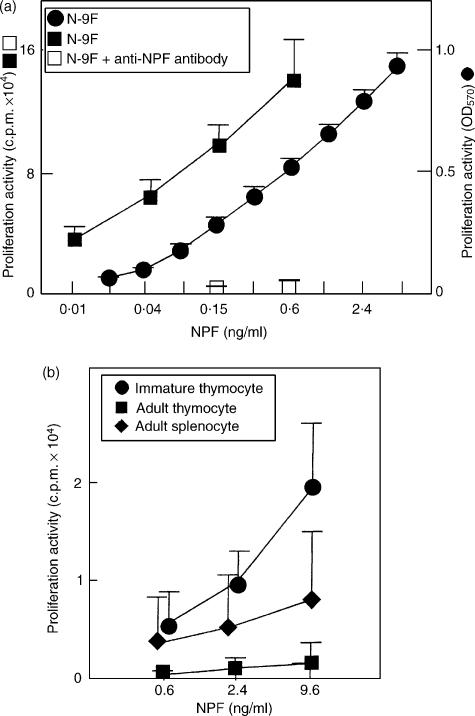

NPF stimulated the proliferation of the N-9F cell clone at concentrations of 0·01–4·8 ng/ml in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3a), and the activity was blocked by a hamster anti-NPF antiserum. NPF also stimulated proliferation of immature mouse thymocytes at E17, but it did not show the proliferation activity on adult mouse thymocytes (Fig. 3b). The splenocytes were scarcely stimulated by NPF, because they produced growth factors such as IL-2.

Figure 3.

N-9F-Proliferation activity of NPF. (a) N-9F cells were cultured with NPF in RPMI-1640 medium, and proliferation of N-9F was measured by an MTT method. N-9F cells were cultured with NPF in the presence or absence of hamster anti-NPF antiserum (2%), and proliferation of N-9F was measured by an incorporation of [3H]thymidine. The mean background is 19 256 c.p.m. (b) Immature thymocytes (E17), adult thymocytes and adult splenocytes were cultured with NPF in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium, and cell proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Mean backgrounds are 565 c.p.m. for immature thymocytes, 492 c.p.m. for adult thymocytes and 4158 c.p.m. for adult splenocytes, respectively. Data represent mean from three to five independent experiments. SD values are shown as error bars.

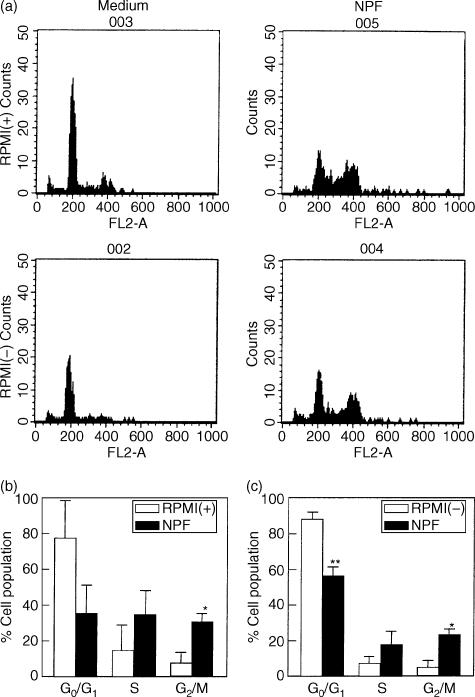

To confirm N-9F proliferation activity of NPF, we investigated the effect of NPF on DNA synthesis of N-9F cells. The analysis by a ModFit software revealed that NPF obviously increased total cell number and the cells in S and G2/M phases when cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with FCS (Fig. 4a,b), suggesting that NPF increased DNA synthesis of N-9F. Although NPF did not affect the cell number in the case cultured in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium, it also showed the same effect as that in the medium containing serum (Fig. 4a,c).

Figure 4.

Effect of NPF on cell cycle of N-9F cells. N-9F cells were cultured with sample in RPMI-1640–10% FCS (RPMI(+)) or serum-free RPMI-1640 (RPMI(–)). DNA content of cells were determined by flow cytometric analysis. (a) Representative flow cytometric analysis. The results from three independent experiments by NPF (2·4 ng/ml) are shown in (b) and (c). Total cell numbers ( × 105) were 0·42 ± 0·27 for medium and 1·09 ± 0·13 (P < 0·05 versus medium) for NPF in RPMI(+), and 0·35 ± 0·17 for medium and 0·28 ± 0·11 for NPF in RPMI(–), respectively. Data represent the mean ± SD. Statistically significant from medium: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

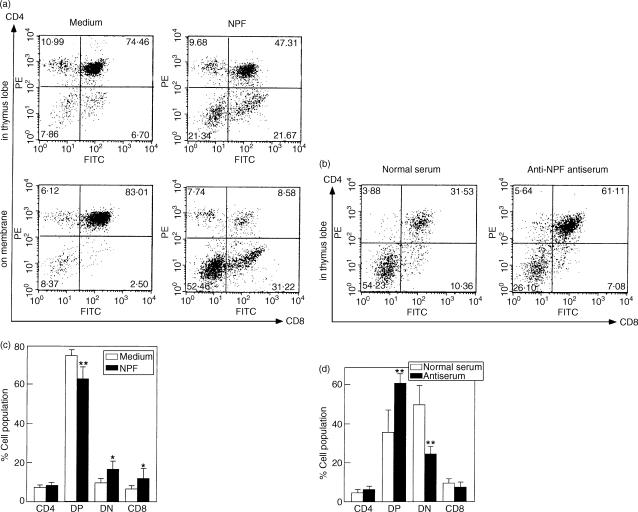

NPF significantly increased total cell number per a thymus lobe in FTOC for 6 days (Fig. 5). It increased the numbers of CD4 and CD8 double negative thymocytes and CD8 single positive thymocytes, and decreased those of CD4 and CD8 double positive thymocytes in thymus (Fig. 5a,c). NPF increased the numbers of the CD4 and CD8 double negative population and the CD8 single positive population and decreased those of the CD4 and CD8 double positive population in thymocytes emigrated on membrane (Fig. 5a). NPF strongly increased the double negative population in all cells in thymus lobe and in emigrants. On the other hand, hamster anti-NPF antiserum (1/50 dilution) decreased the numbers of the CD4 and CD8 double negative population and increased those of the CD4 and CD8 double positive population in FTOC for 4 days (Fig. 5b,d). There were no differences between the cell numbers in thymus lobes treated with normal serum and antiserum. Almost all of thymocytes did not emigrate onto the membrane in FTOC for 4 days. We consider that thymocytes in FTOC grow in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FCS regardless of the presence of hamster normal serum, because FTOC cannot be maintained in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium. Therefore, the result probably showed the effect by which the endogenous NPF was neutralized by hamster anti-NPF antiserum.

Figure 5.

Effect of NPF on FTOC. Thymus lobes from fetal day 14 mice were cultured with NPF or antiserum and stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies. Each of thymocytes in five lobes and all thymocytes emigrated on membrane from five lobes were subjected to flow cytometric analysis. (a) Representative flow cytometric analysis by NPF for 6 days. (b) Representative flow cytometric analysis by hamster anti-NPF antiserum (2%) for 4 days. (c) The results from five lobes by NPF (2·4 ng/ml) are shown. Five independent experiments for thymus lobes and two independent experiments for thymocytes emigrated on membrane were performed with similar results. Total cell numbers ( × 105) per thymus lobe were 2·06 ± 0·50 for medium and 4·04 ± 0·74 (P < 0·05 versus medium) for NPF in thymus lobes, and 1·08 for medium and 1·16 for NPF in thymocytes emigrated on membrane, respectively. (d) The results from 5 lobes by hamster anti-NPF antiserum (2%) are shown. Total cell numbers ( × 105) per thymus lobe were 2·60 ± 0·65 for medium and 2·45 ± 0·43 for NPF, respectively. Data represent the mean ± SD, except thymocytes emigrated on membrane. Statistically significant from medium or normal serum: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

Chemical nature of NPF

By amino acid sequence analysis of NPF, the amino-terminal 20 amino acids, Ser-Leu-Pro-Cys-Asp-Ile-Cys-Lys-Thr-Val-Val-Thr-Glu-Ala-Cys-Asn-Leu-Leu-Lys-Asp-, were successfully identified. This amino-terminal sequence of NPF was in agreement with that of rat saposin A by using a blast search.13,14 The apparent molecular weight of NPF determined by SDS–PAGE and gel filtration was 16 000 (Figs 1 and 2), which was almost identical to the estimated molecular weight of rat saposin A.12,13 Thus, NPF was a rat saposin A-like protein.

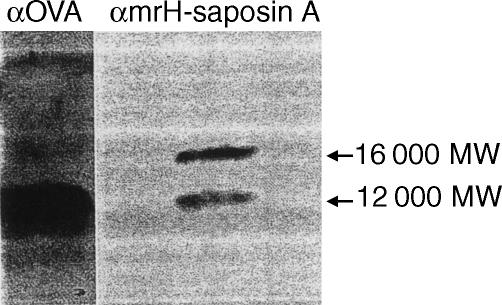

Reactivity of rabbit anti-mrH-saposin A antibody

Western blotting of TCGF with anti-mrH-saposin A antibody gave two positive bands, 16 000 and 12 000 MW (Fig. 6). A 16 000 MW molecule was probably NPF in TCGF. A 12 000 MW molecule was non-specific, because a rabbit anti-ovalbumin antibody also gave a 12 000 MW band.

Figure 6.

Western blotting of TCGF with rabbit anti-mrH-saposin A antibody. Serum-free TCGF concentrated 10-fold was used as TCGF. αOVA: rabbit anti-ovalbumin immunoglobulin G, αNPF: rabbit anti-mrH-saposin A immunoglobulin G.

A serum-free TCGF was applied to an affinity chromatography on a Hitrap-rabbit anti-mrH-saposin A antibody column. The TCGF and fractions bound and unbound to the column were subjected to the N-9F proliferation assay at 2·5% concentration. The activities (OD570 in an MTT method) were 0·455 for TCGF, 0·320 for bound fraction and 0·355 for unbound fraction, respectively. When the fraction unbound to the column was applied to the second affinity chromatography, the activities were 0·288 for bound fraction and 0·160 for unbound fraction, respectively. Both bound and unbound fractions obtained from the third affinity chromatography of the second unbound fraction did not show the activities over a detection limit: OD570 = 0·080. When the bound fraction was applied to ODS-HPLC which used as the means of the final purification of NPF, it gave an apparent peak at the identical retention time (22·1 min) to that of NPF (data not shown). One more experiment for the affinity chromatography was performed with a similar result. Thus, a Hitrap-anti-mrH-saposin A antibody column bound NPF and pulled down the NPF activity in TCGF.

When anti-mrH-saposin A antibody was added to the culture containing TCGF, the antibody did not inhibit the NPF activity in the final concentration of 200 µg/ml (data not shown), indicating that the antibody might bind to the different sites from biologically active site of NPF.

Discussion

A N-9F T-cell clone was isolated as a TCGF-dependent splenic T-cell clone of an athymic mouse, and the cells proliferated on TSC without TCGF.8 The N-9F clone was not maintained by IL-2 alone but required another soluble factor, contained in TCGF for its proliferation.8 Based on these previous findings, we speculated that the molecule(s) on or from TSC, or factor(s) in TCGF is required for N-9F proliferation. We then tried to explore the N-9F proliferation factor from TCGF.

A N-9F-proliferation factor was isolated in a pure form from TCGF (Figs 1 and 2). NPF stimulated the proliferation of N-9F as well as thymocytes from an immature mice at E17, but not that of adult mouse thymocytes (Fig. 3). The effect of NPF on immature thymocytes was weaker than that on N-9F, probably because the primary cells were cultured in serum-free medium. NPF increased N-9F cells in S and G2/M phases (Fig. 4). NPF increased the numbers of CD4 and CD8 double negative thymocytes, and hamster anti-NPF antibody possessing the capacity to neutralize N-9F proliferation activity of NPF decreased those of CD4 and CD8 double negative thymocytes (Fig. 5). These results suggest that NPF affects the double negative thymocytes. NPF also increased CD8 single positive thymocytes (Fig. 5a), indicating that it partly stimulated differentiation, in addition to proliferation of immature thymocytes.15,16 NPF was a novel biological factor possessing proliferation activity for N-9F and thymocytes from immature mice. It has been reported that IL-2 and IL-7 are possible candidates related to proliferation of early thymocytes.3–7,17,18 The importance of the IL-2–IL-2 receptor system for T-cell development has been pointed out by many investigators.3–7,19–21 We previously reported that N-9F did not proliferate with mrIL-2 or mrIL-7.8

Amino-terminal amino acid sequence of NPF was identified and was agree with that of rat sphingolipid activator protein subunit, saposin A.13,14 The apparent molecular weight of NPF, 16 000, was also comparable with that of saposin A (Figs 1 and 2).13,14 Rat saposin A is composed of 84 amino acids highly glycosylated and identical to mouse saposin A except for two amino acids at the 23rd and 35th positions.15,16,22–24 On the other hand, both rat and mouse TCGFs were active for the proliferation of N-9F (unpublished data). Then, rabbit antibody to rmH-saposin A generated from prosaposin cDNA being available was produced. The rabbit anti-mrH-saposin A antibody recognized the 16 000 MW molecule in rat TCGF (Fig. 6). An anti-mrH-saposin A antibody column bound NPF and pulled down the NPF activity in TCGF. Thus, NPF in TCGF was a rat sphingolipid activator protein subunit – a saposin A-like protein – that is to say both rat and mouse saposin A-like proteins seemed to be active for the N-9F proliferation.

The sphingolipid activator protein precursor, prosaposin is distributed in various tissues such as brain, spleen, liver, testis, kidney, etc., and from the results of mRNA expression, protein determination and immunofluorescence studies.14,23,25–27 The evidence that very high levels of mRNA expression were found in macrophage-like cells of spleen, lymph nodes, lung, and thymus in murine immune systems26 suggests that NPF originated mainly from macrophage-like cells of spleen, but it is still unclear if NPF exists in tissues other than spleen.

Prosaposin is synthesized as a 53000 MW protein, post-translationally modified to a 65000 MW form and further glycosylated to a 70 000 MW secretory product.23,28 The 65 000 MW protein is associated with Golgi membranes and is targeted to lysosomes, where four smaller saposins (A, B, C and D) implicated in the hydrolysis of sphingolipids are generated by its partial proteolysis. Saposin A as well as saposin C are thought to function in vivo and in vitro as the activators of the hydrolysis of glucosylceramide by β-glucosylceramidase and galactosylceramidase, though the activity of saposin A is greatly weaker than saposin C.23,28 Although targeted disruption of the prosaposin gene or mutation in the saposin A gene resulted in globoid cell leukodystrophy in the mouse,30–32 any evidence that saposins have a function in immune systems has not been reported.

Recently, evidence has accumulated to show that sphingolipids exert an important function in signalling.33 The ceramide-sphingosine-1-phosphate rheostat regulates T-cell apoptosis.34 Shifting the balance from ceramide to sphingosine-1-phosphate by the activations of ceramidase and shingosine kinase prevents apoptosis.35 Potential raft formation by elevated levels of glycosphingolipids may have a general activating potential on immune cells. Glycosylceramide storage disease (Gaucher's disease) is accompanied by elevated levels of saposins, resulting in chronic stimulation of the humoral immune system.36 Separately, it was reported that saposin C, prosaposin and prosaptide, but not saposin A possessing approximately 60% similarity to saposin C in the amino acid sequence of the prosaptide part, induced a neurotropic effect and cell death prevention in several nerve cells via a G-protein-associated receptor.13,14,37–39 Effective concentrations of saposins A and C for the activation of 4-methylumbelliferyl β-glucosidase were of the order of 10−6−10−5 m,29 and those of saposin C, prosaposin and prosaptide for cell death prevention were of the order of 10−9−10−8 m.34,35 NPF was, however, active for N-9F proliferation at concentrations of 10−12−10−9 m, which could not activate β-glucosidase and induce cell death prevention. Furthermore, the synthetic peptide, prosaptide (Thr-X-Leu-Ile-Asp-Asn-Asn-Ala-Thr-Glu-Glu-Ile-Leu-Tyr, X = D-Ala) active for neurotrophic activity of saposin C did not stimulate N-9F (data not shown). NPF probably stimulates immature T cells in a different mechanism from the β-glucosidase activation by saposins and the interaction of prosaptide to the receptor, but this requires more evidence.

hrH-Saposin A expressed in E. coli did not activate β-glucosidase in vitro.12 mrH-saposin A (3–300 ng/ml) expressed in E. coli did not show N-9F-proliferation activity (data not shown). Also, anti-mrH-saposin A could not neutralize N-9F-proliferation activity of TCGF. These results indicate that at least a part of carbohydrate moieties of NPF are important to express the activity. It was impossible to directly detect carbohydrate in NPF, because the yield of NPF was too little.

Although the physiological role of NPF in immune systems are still obscure, it will contribute to the elucidation of proliferation mechanism of immature T cells as a new proliferation factor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partially by Ministries of Health, Labour and Welfare, and of Education, Science, Culture, Sports and Technology of Japan. We thank Dr Masahiko Tsuda, Nihon University, School of Medicine, for supplying the mouse prosaposin cDNA. We also thank Fuso Pharmaceutical Industry Ltd, Osaka, Japan for amino acid sequencing.

Abbreviations

- FTOC

fetal thymus organ culture

- H

His-tag

- hr

human recombinant

- mr

mouse recombinant

- NPF

N-9F-proliferation factor

- TCGF

T-cell growth factor

- TSC

thymic stromal cell

References

- 1.Von Boehmer H. The developmental biology of T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1987;6:309–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.06.040188.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haynes BF, Markert ML, Sempowski GD, Patel DD, Hale LP. The role of the thymus in immune reconstitution in aging, bone marrow transplantation, and HIV-1 infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:529–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shortman K, Wu L. Early thymocyte progenitors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:29–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson G, Moore NC, Owen JJT, Jenkinson EJ. Cellular interactions in thymocyte development. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:73–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardavin C. Thymic dendritic cells. Immunol Today. 1997;18:350–61. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd R, Chidgey A. T cell development and function- a downunder experience. Immunol Today. 2000;21:472–4. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01723-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small M, Weissman IL. CD3–4–8– Thymocytes precursors with interleukin-2 receptors differentiate phenotypically in coculture with thymic stromal cells. Scand J Immunol. 1996;44:115–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamura H, Kuzuhara H, Hiramine C, Hojo K, Yamamoto H, Fujimoto S. Proliferation of an athymic mouse-derived T cell clone on thymic stromal cells with interleukin-2. Immunology. 1991;74:265–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kisielow PW, Leiserson W, Gordon J. Differentiation of thymocytes in fetal organ culture: analysis of phenotypic changes accompanying the apearance of cytolytic and interleukin-2 producing cells. J Immunol. 1984;133:1117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi X, Leonova T, Grabowski GA. Functional human saposins expressed in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16746–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collard MW, Sylvester SR, Tsuruta JK, Griswold MD. Biosynthesis and molecular cloning of sulfated glycoprotein 1 secreted by rat sertoli cells: sequence similarity with the 70-kilodalton precursor to sulfatides/GM1 activator. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4557–64. doi: 10.1021/bi00412a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morales CR, El AM, Zhao Q, Igdoura SA. Expression and tissue distribution of rat sulfated glycoprotein-1 (prosaposin) J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:327–37. doi: 10.1177/44.4.8601692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikuta K, Kina T, Macneil I, Uchida N, Peault B, Chien Y, Weissman IL. A developmental switch in thymic lymphocyte maturation potential occurs at the level of hematopoietic stem cell. Cell. 1990;62:863–74. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90262-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairchild PJ, Austun JM. Developmental changes predispose the fetal thymus to positive selection of CD4+ CD8+ T cells. Immunology. 1995;85:292–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray R, Suda T, Wrington N, Lee F, Zlotnik A. IL-7 is a growth and maintenance factor for mature and immature thymocyte subsets. Int Immunol. 1989;1:526–31. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.5.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondo M, Weissman IL. Function of cytokines in lymphocyte development. Curr Topic Microbiol Immunol. 2000;251:59–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-57276-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimonkevitz RP, Husmann LA, Bevan MJ, Crispe IN. Transient expression of IL-2 receptor precedes the differentiation of immature thymocytes. Nature 1987. 1987;329:157–9. doi: 10.1038/329157a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkinson EJ, Kingston R, Owen JJT. Importance of IL-2 receptors in intra-thymic generation of cells expressing T-cell receptors. Nature. 1987;329:160–2. doi: 10.1038/329160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tentori L, Longo DL, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Wing C, Kruisbeek AM. Essential role of the interleukin 2 receptor pathway in thymocyte maturation in vitro. J Exp Med 1988. 1988;168:1741–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.5.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuda M, Sakiyama T, Endo H, Kitagawa T. The primary structure of mouse saposin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184:1266–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Brien JS, Kishimoto Y. Saposin proteins: structure, function, and role in human lysosomal storage disorders. FASEB J. 1991;5:301–8. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.3.2001789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito K, Takahashi N, Takahashi A, Shimada I, Arata Y, O'Brien JS, Kishimoto Y. Structural study of the oligosaccharide moieties of sphingolipid activator proteins, saposins A, C and D obtained from the spleen of a Gaucher patient. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:171–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morimoto S, Yamamoto Y, O'Brien JS, Kishimoto Y. Distribution of saposin proteins (sphingolipid activator proteins) in lysosomal strage and other diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:3493–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Whitle DP, Grabowski GA. Developmental and tissue-specific expression of prosaposin mRNA in murine tissues. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1390–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonova T, Qi X, Bencosme A, Ponce E, Sun Y, Grabowski GA. Proteolytic processing patters of prosaposin in insect and mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17312–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igdoura SA, Rasky A, Morales CR. Trafficking of glycoprotein-I (prosaposin) to lysosomes or to the extracellular space in rat Sertoli cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1996;283:385–94. doi: 10.1007/s004410050549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morimoto S, Martin BM, Yamamoto Y, Kreith KE, O'Brein JS, Kishimoto Y. Saposin A. second cerebrosidase activator protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3389–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujita N, Suzuki K, Vanier MT, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse sphingolipid activator protein gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:711–25. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuda J, Vanier MT, Saito Y, Tohyama J, Suzuki K, Suzuki K. A mutation in the saposin A domain of the sphingolipid activator protein (prosaposin) gene results in a late-onset, chronic form of globoid cell leukodystrophy in the mouse. 2001;10:1191–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.11.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuda J, Vanier MT, Saito Y, Suzuki K, Suzuki K. Dramatic phenotypic improvement during pregnancy in a genetic leukodystrophy: estrogen appears to be a critical factor. 2001;10:2709–15. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.23.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prieschl EE, Baumruker T. Sphingolipids: second messengers, mediators and raft constituents in signaling. Immunol Today. 2000;21:555–60. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01725-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basu S, Bayoumy S, Zhang Y, Lozano J, Kolensnick R. BAD enables ceramide to signal apoptosis via Ras and Raf-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30419–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuvillier O, Pirianov G, Kleuser B, Vanek PG, Coso OAJS, Gutkind JS, Spiegel S. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 1996;381:800–3. doi: 10.1038/381800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoenfeld Y, Gallant LA, Shaklai M, Livni E, Djaldetti M, Pinkhas J. Gaucher's disease: a disease with chronic stimulation of the immune systems. Arch Pathol Laboratory Med 1982. 1982;106:388–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiraiwa M, Taylor EM, Campana WM, Darin SJ, O'Brein JS. Cell death prevention, mitogen-activated protein kinase stimulation, and increased sulfatide concentrations in Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes by prosaposin and prosaptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4778–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuboi K, Hiraiwa M, O'Brien JS. Prosaposin prevents programmed cell death of rat cerebellar granule neurons in culture. Dev Brain Res. 1998;110:249–55. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiraiwa M, Campana WM, Martin BM, O'Brien JS. Prosaposin receptor: evidence for a G-protein-associated receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:415–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]