Abstract

Background

The glutamate synthase operon (gltBDF) contributes to one of the two main pathways of ammonia assimilation in Escherichia coli. Of the seven most-global regulators, together affecting expression of about half of all E. coli genes, two were previously shown to exert direct, positive control on gltBDF transcription: Lrp and IHF. The involvement of Lrp is unusual in two respects: first, it is insensitive to the usual coregulator leucine, and second, Lrp binds more than 150 bp upstream of the transcription starting point. There was indirect evidence for involvement of a third global regulator, Crp. Given the physiological importance of gltBDF, and the potential opportunity to learn about integration of global regulatory signals, a combination of in vivo and in vitro approaches was used to investigate the involvement of additional regulatory proteins, and to determine their relative binding positions and potential interactions with one another and with RNA polymerase (RNAP).

Results

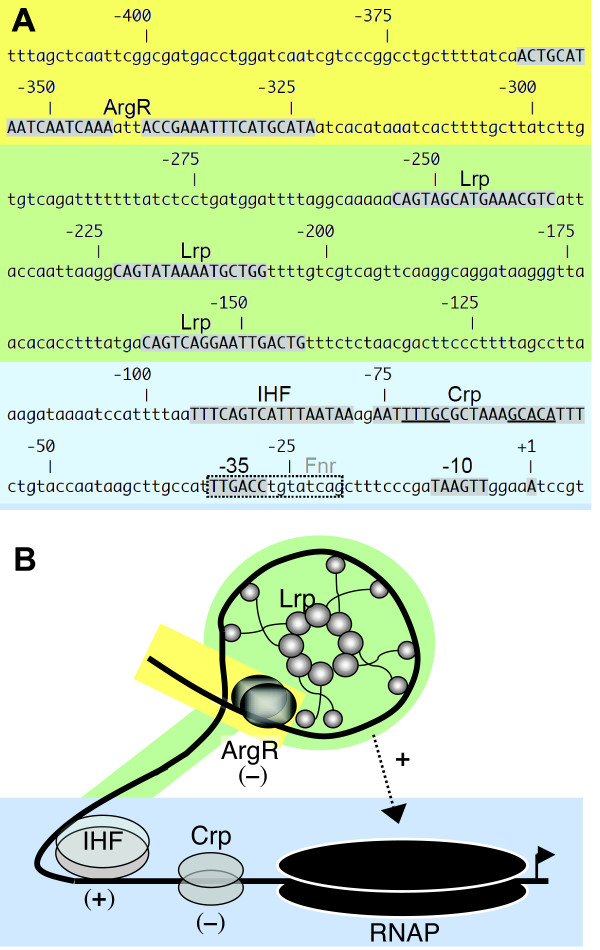

Crp and a more local regulator, ArgR, directly control gltBDF transcription, both acting negatively. Crp-cAMP binds a sequence centered at -65.5 relative to the transcript start. Mutation of conserved nucleotides in the Crp binding site abolishes the Crp-dependent repression. ArgR also binds to the gltBDF promoter region, upstream of the Lrp binding sites, and decreases transcription. RNAP only yields a defined DNAse I footprint under two tested conditions: in the presence of both Lrp and IHF, or in the presence of Crp-cAMP. The DNAse I footprint of RNAP in the presence of Lrp and IHF is altered by ArgR.

Conclusion

The involvement of nearly half of E. coli's most-global regulatory proteins in the control of gltBDF transcription is striking, but seems consistent with the central metabolic role of this operon. Determining the mechanisms of activation and repression for gltBDF was beyond the scope of this study. However the results are consistent with a model in which IHF bends the DNA to allow stabilizing contacts between Lrp and RNAP, ArgR interferes with such contacts, and Crp introduces an interfering bend in the DNA and/or stabilizes RNAP in a poised but inactive state.

Background

A small number of global regulatory proteins appear to play a central role in integrating the regulatory architecture of Escherichia coli, so as to promote coherent transcriptional responses to environmental changes. Just seven proteins (ArcA, Crp, FIS, Fnr, IHF, Lrp, and NarL) directly control expression of about half of all genes in E. coli [1]. We report here direct evidence that three of these seven proteins, plus a more specific regulator, cooperate to control an operon critical to nitrogen metabolism.

There are two main pathways for assimilating ammonia into glutamate in Escherichia coli [2] (see Fig. 1). In the presence of high ammonia concentrations and limited carbon/energy, glutamate dehydrogenase (GdhA) produces glutamate from ammonia, α-ketoglutarate, and NADPH [equation 1, and left side of Fig. 1].

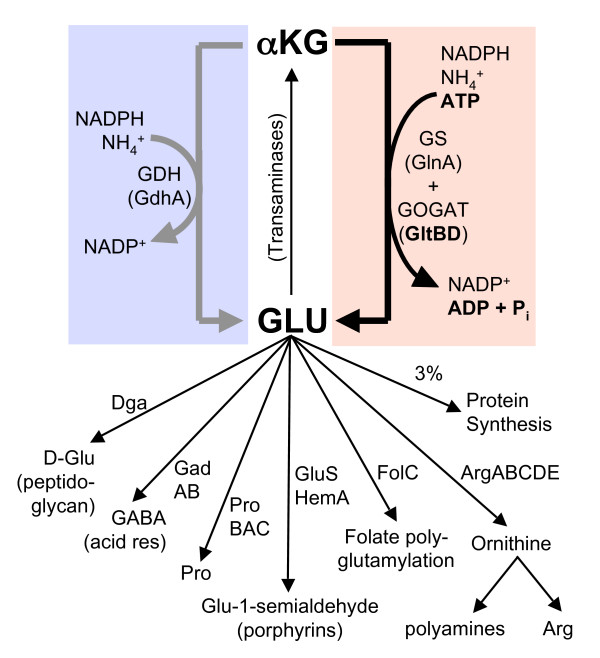

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis and metabolic uses of L-glutamic acid. The two alternative pathways from α-ketoglutarate (αKG) to glutamate (Glu) are shown by the thick arrows, as described by equations 1–4 in the Introduction. The gray arrow (left) represents equation 1, while the black arrow (right) represents the net sum of equations 2 and 3 (i.e., equation 4). Glu is one of the small minority of amino acids for which the great bulk of the molecules are used for purposes other than direct incorporation into proteins [2]. A number of transaminases use the α-amino group of Glu. Other uses of Glu were identified from the BioCyc website [63].

NH4+ + α-Ketoglutarate + NADPH → Glutamate + NADP+ [1]

At low ammonia concentrations, a two-enzyme cycle is used instead. First, glutamine synthetase (GlnA) produces glutamine from ammonia, glutamate and ATP [equation 2]. Then glutamate synthase (GltBD) produces two molecules of glutamate from glutamine, α-ketoglutarate, and NADPH [equation 3], with one of the glutamate molecules going back into the cycle and the other representing net ammonia incorporation [equation 4, and right side of Fig. 1]. The only difference between equations [1] and [4] is the involvement of ATP.

NH4+ + Glutamate + ATP → Glutamine + ADP + Pi [2]

Glutamine + α-Ketoglutarate + NADPH → 2 Glutamate + NADP+ [3]

NH4+ + α-Ketoglutarate + NADPH + ATP → Glutamate + NADP+ + ADP + Pi [4]

In the presence of high ammonia levels, GltBD activity would waste ATP as a result of unnecessary glutamine turnover. The pathway represented by equation 4 is estimated to account for a remarkable 15% of total ATP turnover during growth in glucose minimal medium [2], so the ATP wastage would be substantial. However, insufficient GltBD activity in the face of dropping ammonia levels would lead to cessation of growth [3,4] and a competitive disadvantage. Clearly the level of GltBD must be very carefully controlled so as to anticipate the probable near-term needs of the cell.

Our interest in gltBDF, the operon that includes structural genes for GltBD, stems from its membership in the regulon controlled by Lrp (leucine-responsive regulatory protein) [5]. There is no obvious single role for Lrp, but three broad themes stand out. First, Lrp appears to sense the shift between two major E. coli environments, "the gut and the gutter" [6], activating many amino acid biosynthetic operons (such as gltBDF) and repressing many catabolic ones. Second, and partially overlapping the first, Lrp plays an important role in regulating nitrogen metabolism [2,5,7]. Third, Lrp appears to play an important role in preparing the cell for stationary phase [6,8-13].

In the gltBDF operon, IHF binds the region from -75 to -113, while the three Lrp binding sites are centered at nucleotides -152, -215 and -246 relative to the transcription start site [5,14] (Fig. 2A). This arrangement leaves space for other proteins to bind, and it seemed likely that additional regulators would be involved in controlling a pathway that can account for 15% of the cell's ATP flux. There is some evidence for effects (direct or indirect) of other regulators on gltBDF expression, including Crp [15], Fnr [16], Nac [17], and GadE [18] (see information on the gltBDF operon at EcoCyc.org [19]). We report here that gltBDF is directly and negatively controlled by Crp and ArgR, in addition to the direct positive control by Lrp and IHF. We also show that RNAP binds stably to the gltBDF promoter in the presence of Lrp and IHF, or in the presence of Crp-cAMP.

Figure 2.

gltBDF promoter region. A. Sequence of region upstream of gltB. Nucleotides shown as shaded capitals represent promoter elements or binding sites for the indicated regulatory proteins, as identified in this work and earlier studies (see references in text). The borders shown for binding sites are based on comparison to consensus sequences, and are consistent with DNAse I footprints reported in this study. The binding site for Fnr is shown as a dashed box because it has not been experimentally confirmed (see information on gltBDF at BioCyc.org). The color-shaded background indicates three broad regions of the promoter (initiation region, blue; Lrp-binding region, green; ArgR-binding region, yellow). B. A model for gltBDF transcriptional regulation. Lrp and IHF bind and, according to the model, bend gltBDF promoter DNA such that an upstream regulatory sequence or Lrp surface required for stable binding of RNAP is brought in contact with RNAP that is loosely associated with the promoter region. This positive interaction (and not Lrp binding) is partially abolished by ArgR-Arg bound to glt DNA. In the presence of Crp-cAMP, RNAP association with the promoter is stabilized but in a nonproductive manner, leading to transcriptional repression. Background shading matches that in part A.

Results

Effects of Lrp and IHF on RNAP binding to the gltBDF promoter region

We have previously shown that Lrp and IHF bind simultaneously to gltBDF promoter (PgltB) DNA, yielding a band with intermediate gel shift mobility between the IHF-DNA and Lrp-DNA complexes (Fig. 3C in [14]). Fig. 3A shows that the Lrp-binding region yields a subtly altered Lrp-dependent DNAse I footprint in the presence of IHF, though the IHF footprint is not obviously changed by the presence of Lrp.

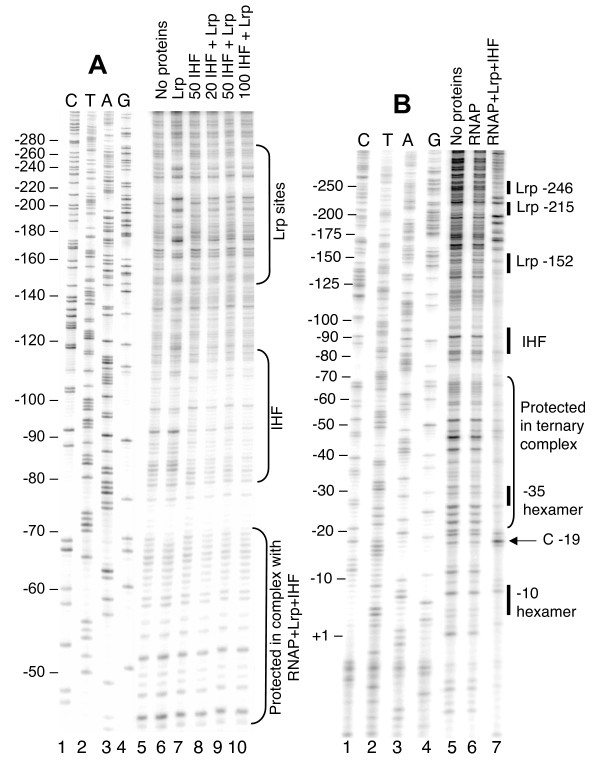

Figure 3.

DNAse I protection of the gltBDF promoter region by Lrp, IHF, and RNA polymerase. A. DNase I protection assay of gltBDF promoter region in the presence of both Lrp and IHF. A fragment of gltB DNA from -325 to +8 was used in the reaction. The first 4 lanes represent a sequencing ladder of the region. In all cases where it was added, Lrp was used at 2 nM. The amounts of IHF are shown in nM. B. A fragment of gltB DNA from -571 to +51, labeled at the +51 end of the template strand using 32P, was used. When present, the concentration of RNAP was 30 nM, Lrp 100 nM and IHF 100 nM. The first 4 lanes represent a sequencing ladder of the template strand of the region.

RNA polymerase holoenzyme (RNAP) binds to PgltB in the absence of other proteins, as revealed by electrophoretic mobility shift of a DNA segment from -406 to +131 (relative to the transcription start; not shown). However DNAse I footprinting analysis of this binary complex revealed no obvious regions of protection (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 5 and 6). Since the absence of either Lrp or IHF leads to a >30-fold reduction in gltBDF transcription [5,14], we investigated whether these two proteins influence RNAP binding to PgltB. Mobility shift experiments were not informative as, under our conditions, the large shift due to RNAP alone was indistinguishable from shifts due to RNAP together with Lrp and/or IHF. However DNAse I protection analysis revealed that the combination of Lrp, IHF and RNAP results in a footprint in the promoter region, with strongly enhanced cleavage at the -19 position of the template strand and protection in the remainder of the region between the -10 and -35 hexamers (Fig. 3B, compare lane 7 to lanes 5 and 6). This protection extended ~30 bp upstream of the -35 hexamer, merging with the footprint of IHF, and some protection was visible even farther upstream between the IHF and Lrp binding sites. A combination of just Lrp and IHF does not result in any additional footprint aside from those of the individual proteins [14], and in particular the extended protection upstream of the -35 hexamer is not seen in the absence of RNAP (Fig. 3A).

Crp-cAMP regulation of gltBDF transcription

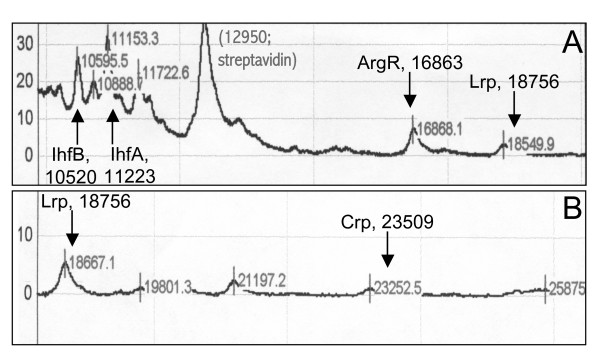

We searched for proteins from an E. coli whole-cell extract that bound to immobilized, biotinylated PgltB DNA, using Ciphergen ProteinChips™ and mass spectrometry. This method had previously implicated IHF as a factor involved in gltBDF regulation, as we subsequently confirmed [14], but additional mass peaks representing other DNA binding proteins had not yet been investigated. The analysis suggested ArgR (regulator for the arginine regulon) and Crp (catabolite repressor protein) as potential additional regulators of gltBDF (Fig. 4). Several decades ago Prusiner et al. reported negative regulation of glutamate synthase expression by Crp [15]. Specifically, glutamate synthase activity is doubled in a mutant lacking adenylate cyclase (cya), and reduced 1.5-fold by addition of exogenous cAMP or growth with glycerol as the carbon source (which increases cAMP levels) [15]. However, it was not determined whether these results involved direct interactions between Crp and PgltB.

Figure 4.

Masses of polypeptides associated with gltB DNA in vitro. Surface-enhanced laser desorption and ionization (SELDI; Ciphergen Biosystems) was used to identify proteins from whole-cell E. coli extracts binding to biotin-labeled gltB DNA (from -406 to +246). The DNA was attached to streptavidin-coated chips, incubated with the extracts, and washed prior to mass analysis. Parts A and B show different mass ranges. The vertical arrows indicate the theoretical positions of the indicated polypeptides; in each case the mass shown assumes removal of the N-terminal methionine.

Our inspection of the gltBDF DNA sequence revealed a potential Crp-binding site between -76 and -55 (Fig. 5A, top two lines). We have not attempted to measure transcription of a gltB-lacZ fusion in isogenic crp and crp+ strains, to complement the earlier data of Prusiner et al. [15]. This is because the crp mutant grows much more slowly than its isogenic partner [20], and comparisons would be complicated by the different growth rates [21]. However we have taken three complementary approaches to demonstrate a direct effect of Crp-cAMP on glt transcription.

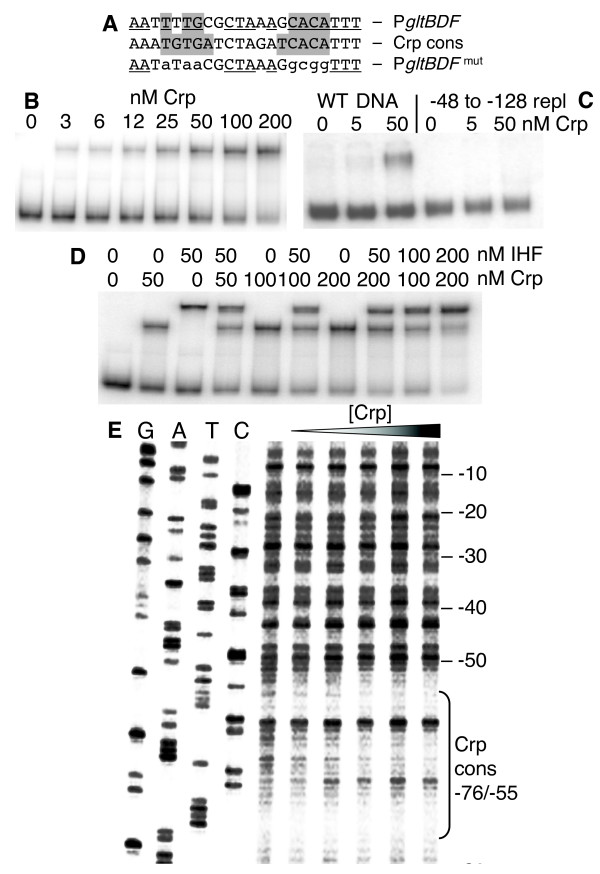

Figure 5.

Interactions between Crp and the gltBDF promoter region. A. The glt Crp-binding sequence (top) compared to the consensus Crp binding sequence (middle). The most-conserved elements of the Crp sequence are shaded, and matches to the consensus are underlined. The bottom sequence shows the mutations (lowercase) that were introduced for the experiment shown in Fig. 6. B. Gel mobility shift analysis of Crp binding to glt DNA region -406 to +246. The running buffer and gel contained 20 μM cAMP. C. Gel mobility shift analysis as in (B), except that two DNAs are used. One is WT, and the other has the region from -128 to -48 replaced by an equal length of exogenous DNA (amplified from the coding region of the cat gene). D. Gel mobility shift assay showing simultaneous binding of Crp and IHF to gltBDF DNA. A fragment of gltB DNA from -203 to +8 was used in the assay. E. DNAse I protection of glt DNA by Crp binding. A gltB DNA fragment from -203 to +161 labeled at the -203 end of the partner strand was used for the assay. The first 4 lanes represent the sequencing ladder of the partner strand. Crp concentrations of 0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 and 200 nM were used in the assay.

First, we carried out mobility shift assays using purified Crp and a gltBDF DNA fragment containing the region from -406 to +246. Crp bound the glt DNA with an apparent Kd of 35 nM in the presence of 20 μM cAMP (Fig. 5B). Replacing the region between -121 and -48 with heterologous DNA [14] resulted in loss of detectable binding (Fig. 5C). When cAMP was not added to the gel, but was present in the binding reaction, binding was still observed but the shifted bands were smeared, suggesting that the complexes were unstable under this condition (not shown).

Second, we carried out DNAse I footprint analyses, using purified Crp, cAMP, and PgltB DNA. A defined region of partial protection was seen between -71 and -52 on the non-template strand (Fig. 5E), and -72 to -57 on the template strand (not shown). Thus Crp-cAMP interacts directly with PgltB. The Crp binding is centered at -65.5, in the predicted binding sequence (-76 to -55), and between the -35 hexamer and the IHF binding site (Fig. 2A).

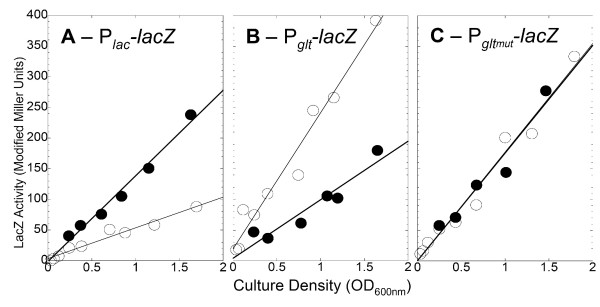

Third, we determined the effects of the membrane-permeable derivative dibutyryl-cAMP on expression of gltB-lacZ with and without alteration of the Crp binding sequence. The alterations are shown in Fig. 5A (bottom line), and replace all of the most highly-conserved nucleotides of known Crp-binding sequences (shaded) that were not already different in the native gltBDF promoter. Concentrations of dibutyryl-cAMP as high as 50 μM had no effect on the growth rate of the cultures (not shown), and we used 10 μM in the experiments described here. As a control, parental strain W3110 (with an intact lac operon) was grown in a defined glucose rich medium plus the inducer IPTG. As shown in Fig. 6A, dibutyryl-cAMP had the expected effect of increasing lacZ expression in the parental strain, due to relief of catabolite repression [22]. In contrast, Fig. 6B shows that dibutyryl-cAMP reduced expression of lacZ fused to WT PgltB, while Fig. 6C shows that dibutyryl-cAMP had no effect on lacZ fused to PgltB having the altered Crp binding sequence. Similar results were obtained in glucose minimal medium (not shown).

Figure 6.

Effects of dibutyryl-cAMP on expression from PgltBDF and a mutant form with altered Crp binding sites. Cells were grown in a MOPS-based defined glucose rich medium with (closed symbols) or without (open symbols) 10 μM dibutyryl-cAMP. All strains were Crp+. A. Expression of the native lac operon (strain W3110). B. Expression of a PgltBDF-lacZ fusion (strain PM2003). C. Expression of a fusion of lacZ to the mutant version of PgltBDF shown in the bottom line of Fig. 5A (strain PM2004).

As Crp most often acts as a transcription activator, we explored some possible explanations for its repressive effect on PgltB. One possibility, given the proximity of the Crp and IHF binding sites (Fig. 2A), and the requirement of IHF for activation by Lrp [14], is that Crp interferes with IHF binding. However mobility shift analysis indicates that Crp and IHF bind independently of one another (Fig. 5D), though the ternary and binary complexes could not be resolved from one another well enough to completely rule out limited negative (or positive) cooperativity in their binding.

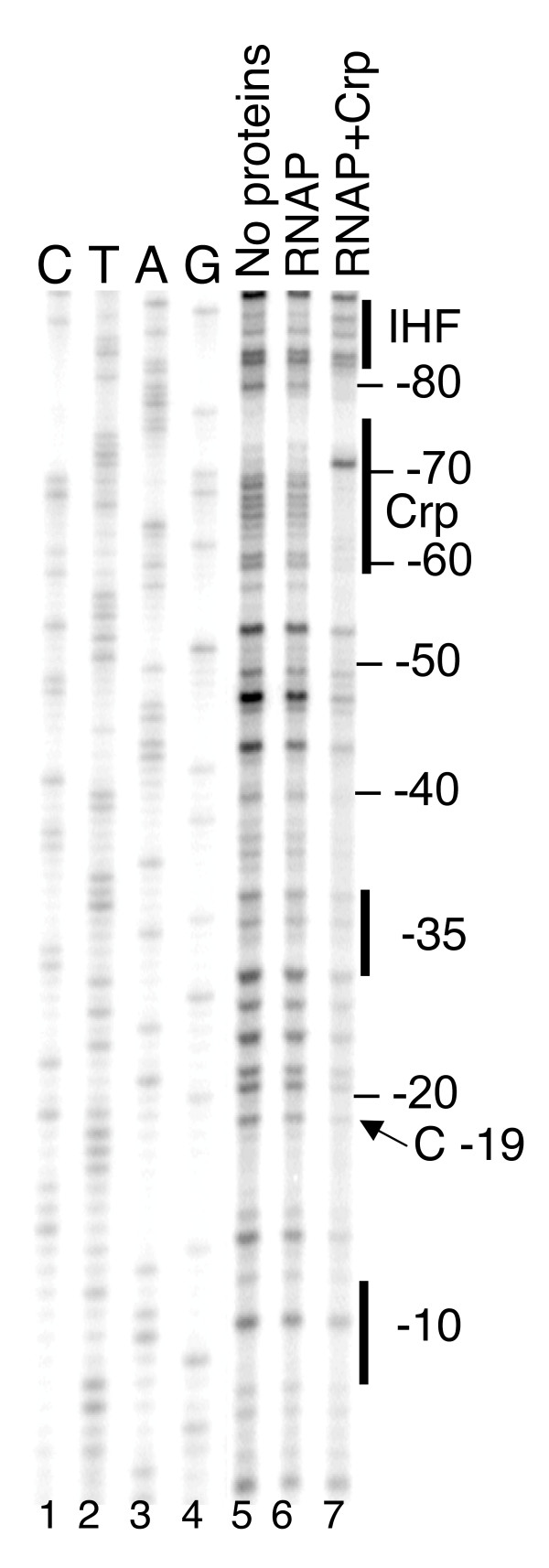

A second possibility, which we did not test, is that the Crp-induced bend in the DNA [23] opposes that generated by IHF, preventing proper activation. A third possibility is that Crp interferes with RNAP binding. As noted above, RNAP alone fails to yield a clear protection pattern on PgltB DNA. Adding Crp-cAMP, far from interfering with RNAP binding, resulted in the appearance of a well-defined pattern of RNAP-dependent protection (Fig. 7). This pattern is, however, distinct from that seen when the coactivators Lrp and IHF are added in place of Crp (Fig. 3B). One particularly striking difference, as an example, is the DNase cleavage at position -19, that shows hypersensitivity in the presence of Lrp + IHF but not in the presence of Crp (compare lane 7 of Fig. 3B to lane 7 of Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of Crp on protection of the gltBDF promoter by RNAP. A fragment of gltBDF DNA from -571 to +51, labelled at the +51 end was used for DNase I protection assays. The first 4 lanes represent a sequencing ladder of the region. RNAP was used at 30 nM and Crp at 100 nM. Reactions with CRP contained 2mM cAMP.

ArgR-Arg regulation of gltBDF transcription

The Ciphergen ProteinChip™ analysis referred to above yielded another E. coli polypeptide bound to PgltB DNA, having a molecular mass close to that of the regulatory protein ArgR (Fig. 4A). The involvement of ArgR in gltBDF regulation is reinforced by the following three observations. First, adding 7.5 mM L-arginine to MOPS-glucose medium nearly halved LacZ activity, in the gltB-lacZ fusion strain LP1000 (and its isogenic rph+ strain LP2020; see below) (Table 1). Second, deleting argR from strains LP1000 (LP1050) or LP2020 (LP2023) doubled LacZ activity. Third, adding arginine to the growth medium did not affect LacZ levels in the ΔargR strain LP1050.

Table 1.

Effects of arginine and ArgR on gltB::lacZ expression

| Effect tested | Strain/condition | LacZ activity (units)1 | Normalized data |

| LP1000 (rph) | 11722 | (1.00) | |

| Addition of arginine3 | LP1000 + Arg | 660 | 0.56 |

| LP1270 | 900 | 0.77 | |

| LP1270 + Arg | 953 | 0.81 | |

| LP2020 (rph+) | 736 | 0.63 | |

| LP2020 + Arg | 402 | 0.34 | |

| Deletion of ArgR | LP1050 (ΔargR) | 2981 | 2.54 |

| LP1050 + Arg | 3035 | 2.59 | |

| LP2020 (rph+)4 | 648 | 0.55 | |

| LP2023 (rph+ ΔargR) | 1283 | 1.09 | |

1 One unit of LacZ (β-galactosidase) activity is defined as 1 nmol of ONPG hydrolyzed per min.

2 Samples were taken at several culture densities, and the resulting LacZ activity was plotted vs. culture density (as in Fig. 6). The activity was calculated from the slope of the line; in every case, the correlation coefficient of the least squares regression was ≥ 0.99.

3 Arginine hydrochloride was added to the medium to a final concentration of 7.5 mM.

4 These results were obtained on a different day from the other experiments.

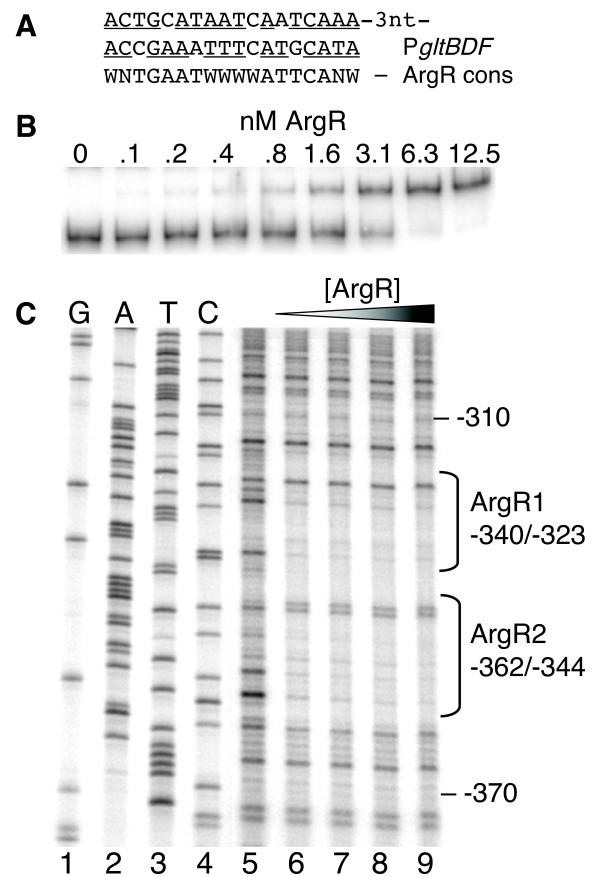

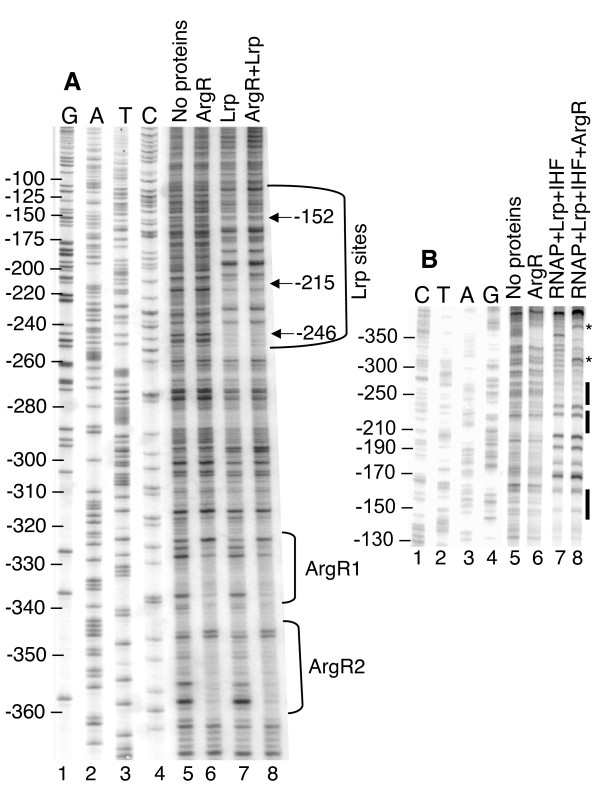

We have evidence that ArgR mediates its regulatory effect on the gltBDF promoter via direct interaction. There are two good matches to the consensus ArgR binding site sequence [24,25] upstream of the promoter-distal Lrp binding site (Figs. 2A and 8A). When gltBDF DNA containing the putative ArgR sites upstream of -270 was deleted, arginine had no effect on gltB-lacZ expression (strain LP1270, Table 1). We extended this observation by using purified ArgR in mobility shift and DNAse I footprint analyses. ArgR bound to gltB DNA (-406 to +246) with a Kdapp of 1.8 ± 0.7 nM (Fig. 8B), and to a 3'-shortened fragment (-406 to -128) with essentially the same affinity (Kdapp of 1.7 ± 0.06 nM; not shown). These data were fitted using the Hill equation as previously described [26-28], and both binding curves were characterized by a Hill coefficient of 2.0, indicating that multiple ArgR molecules are binding cooperatively.

Figure 8.

Interactions between ArgR and the gltBDF promoter region. A. The ArgR-binding sequences upstream of gltBDF (top two lines) compared to the symmetrical consensus ArgR-binding site [64]. Matches to the consensus are underlined. W = A or T, and N = A, C, G or T. B. Gel mobility shift analysis of ArgR binding to the region -406 to +246 of glt DNA. L-arginine was present in the reactions, the gel and running buffer (see Methods). C. DNase I protection assay of the region -462 to +161 bp upstream of gltBDF, labelled at the -462 end of the partner strand. The first 4 lanes represent a sequencing ladder of the partner strand in this region. ArgR concentrations of 0, 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, and 25 nM were used, and 5 mM L-arginine was present.

The sequence to which ArgR binds was determined by DNase I protection using gltB DNA from -462 to +161. ArgR protected a region upstream of the distal Lrp binding site (Figs. 2A and 8C), extending from -361 to -318 on the non-template strand. This encompasses the two ArgR consensus-matching sites, and is consistent with the Hill coefficient of 2.0. Similar results were obtained for the template strand (not shown; a longer fragment, extending from -575 to +131, gave lower resolution due to the position of the footprint on the fragment).

We considered two possibilities for the basis of gltBDF repression by ArgR. First, given the proximity of the ArgR and Lrp binding sites (Fig. 2A), we tested whether ArgR interfered with Lrp binding. Mobility shift assays with ArgR and Lrp were inconclusive in this respect, because adding the corepressor arginine to the gel prevented the Lrp-DNA complex from migrating far into the gel (not shown). However DNAse I footprint analyses suggest that Lrp and ArgR bind independently of one another (Fig. 9A).

Figure 9.

Effect of ArgR on protection of the gltBDF promoter by RNAP and Lrp. The first 4 lanes represent the sequencing ladder of the region. A. A gltBDF DNA fragment from -462 to +161 labeled at the -462 end was used. The concentrations of both Lrp and ArgR were 25 nM. B. A fragment of gltBDF DNA from -571 to +51, labeled at the +51 end was used. The concentrations of proteins used were as follows: ArgR 25 nM, RNAP 50 nM, Lrp 25 nM and IHF 50 nM. Reactions contained 5 mM L-arginine.

A second possible basis for repression of gltBDF by ArgR involves interference with the proposed Lrp-RNAP interaction. ArgR does in fact alter the protection pattern generated by the combination of Lrp, IHF, and RNAP (Fig. 9B, asterisks). In the absence of ArgR there is a limited region of RNAP-dependent hypersensitivity that overlaps the ArgR binding site; addition of ArgR and arginine alters this hypersensitivity pattern.

Effects of rph on gltBDF expression

We considered the possibility that our measurements of gltBDF expression were being affected by a defect in the E. coli W3110 background. This commonly-used K-12 strain carries a frameshift mutation in rph, the structural gene for RNAsePH, that results in decreased pyrE (orotate phosphoribosyltransferase) expression and in turn leads to pyrimidine limitation during growth in minimal media [29]. Pyrimidine biosynthesis is regulated by feedback inhibition, so it seemed plausible that W3110 would sense increased demand for glutamate (to provide needed glutamine precursors), and would thus have elevated gltBDF expression. Consistent with this possibility, adding 20 μg/ml of the pyrimidine uracil to strain LP1000 in minimal medium resulted in a 1.5 fold reduction of PgltB-lacZ activity (strain LP1000 is a W3110 derivative carrying a gltB-lacZ fusion in a Δlac background). We replaced the W3110 rph allele with the wild-type gene (see Methods), and the new strain was designated LP2002. Correcting the rph mutation roughly halved transcription from PgltB in strain LP2020 (strain LP2002 bearing Δlac and a gltB-lacZ fusion, see Table 2), in agreement with the uracil addition results. Strain LP2002 may be generally useful for studies of E. coli physiology.

Table 2.

E. coli strains1, plasmids, and primers used in this work

| Strain/plasmid/primer | Description | Source or reference |

| Strains | ||

| BE3471 | PS2209 gltB (psiQ39)::lacZ (Mu d1-1734) | [28] |

| BE3479 | PS2209 gltB (psiQ32)::lacZ (Mu d1-1734) | [28] |

| BE3779 | PS2209 gltB (psiQ32)::lacZ (Mu d1-1734) lrp-35::Tn10 | [28] |

| BL21(DE3) | F- ompT hsdSB (rB-mB-) gal dcm (DE3) | Novagen |

| JWD3 | BE1 (W3110 lrp-201::Tn10) pJWD2 | [28] |

| LP1000 | PS2209 gltB::lacZ transcriptional fusion at λatt with -406 to +246 of the gltBDF operon | [14] |

| LP1050 | LP1000 ΔargR | This work |

| LP1060 | BL21DE3/pLP1060 | This work |

| LP1070 | BL21DE3/pLP1070 | This work |

| LP1080 | BL21DE3/pLP1080 | This work |

| LP1270 | PS2209 gltB::lacZ transcriptional fusion at λatt with -270 to +246 of the gltBDF operon | This work |

| LP2002 | W3110 rph+ | This work |

| LP2010 | LP2002 ΔlacZYA | This work |

| LP2020 | LP2010 gltB::lacZ transcriptional fusion at λatt with -406 to +246 of the gltBDF operon | This work |

| LP2023 | LP2020 ΔargR | This work |

| PM2003 | PS2209/pPM2005 | This work |

| PM2004 | PS2209/pPM2006 | This work |

| PS2209 | W3110 Δlac-169 | F. C. Neidhardt |

| W3110 | F- prototroph rph | F. C. Neidhardt |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 Δlac-pro [F' proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10] | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBH403 | pKK232-8 with promoterless lacZ gene inserted upstream of cat gene in a derivative of pBR322 | [61, 62] |

| pPM2005 | pBH403 with gltB promoter region cloned from BamHI to SalI | This work |

| pPM2006 | pPM2005 with mutations in the Crp-binding sequence | This work |

| PJWD2 | pTrc99A (Pharmacia) with the lrp coding sequence cloned into the NcoI site | [28] |

| pLP1060 | pET23b (Novagen) with the argR coding sequence cloned into the NdeI/XhoI sites | This work |

| pLP1070 | pET29a (Novagen) with the crp coding sequence inserted into the NdeI/XhoI sites | This work |

| pLP1080 | pET28A (Novagen) with the himA and himD coding sequences inserted in tandem into the NcoI//BamHI sites | This work |

| pGEMT-easy | Cloning vector | Promega |

| pKO3 | Suicide vector | [54] |

| Primers | ||

| arg1 | CGCCAGCAGCGCCGAGGACTGCGAC | |

| arg2 | CACTAATTATTGAGCTAATTAATACCGCGC | |

| arg3 | CATATGCGAAGCTCGGCTAAG | |

| arg4 | CTCGAGTTATTAAAGCTCCTGGTCGAACAGCTC | |

| crp5 | CCATATGGTGCTTGGCAAACCGC | |

| crp6 | CCTCGAGTTAACGAGTGCCGTAAACGAC | |

| gltP1 | CGGGATCCCATAATCACATAAATCACTTTTGCTTATC | |

| gltP2 | ACGCGTCGACAGCGGATTTCCAACTTATCG | |

| gltcrp12 | CAGTCAATTAATAAAGAATATAACGCTAAAGGCGGTTTCTGTACCAATAAGCTTGCC | |

| gltcrp2 | GGCAAGCTTATTGGTACAGAAACCGCCTTTAGCGTTATATTCTTTATTAATTGACTG | |

| himA1 | GGTACCGGCATCATTGAGGGATTGAACCTATGGCGCTTACA | |

| himA2 | CTCGAGCTCGTCTTTGGGCGAAGC | |

| himD1 | GGTACCTTAACCGTAAATATTGGCGCGATCGCG | |

| himD2 | TCATGACCAAGTCAGAATTGATAGAAGAC | |

| lac6 | GGATACGACGATACCGAAGACAGCTCATG | |

| lac7 | CGAGCCGGAAGCATAAAGTGTAAAGC | |

| lac8 | GCTTTACACTTTATGCTTCCGGCTCGGGCGTTCCTTGTCGGGTTATTCG | |

| rph1 | GCGTCTGATCGCCCGTGCTCTTCGCGC | |

| rph23 | CGTCGCTACAATGGATTCGATTCCCCCTCGGGC | |

| rph33 | GCCCGAGGGGGAATCGAATCCATTGTAGCGACG | |

| rph4 | ACGGCAGGTCCAGGTCGTGATGCTCCG | |

1All strains are Escherichia coli K-12.

2The underlined bases alter the Crp-binding site in the gltBDF promoter.

3The underlined italic base is inserted to replace the base deleted in the rph mutation.

Discussion

Role of IHF in mediating activation of gltBD by Lrp

IHF, a DNA-bending protein [30], is required for activation of gltBDF transcription by Lrp [14]. IHF subtly affects the Lrp-dependent DNAse I footprint (Fig. 3A), suggesting that IHF alters the Lrp-DNA complex (or alters DNAse I access to that complex). In addition, IHF bending could bring the Lrp-DNA complex into activating contact with RNAP at PgltB (Fig. 2B). IHF plays an architectural role at several activated promoters, such as PilvP [31]. We have not directly demonstrated looping, but two results support this view. First, no defined footprint for RNAP was seen at PgltB with either IHF or Lrp alone, only with both together (Fig. 3B and our unpublished results). Second, an earlier study demonstrated that a 5 bp (half helical turn) insertion between the proximal Lrp binding site and the promoter reduced gltB-lacZ expression 3-7-fold, while a 10 bp (full helical turn) insertion at the same location did not reduce fusion expression (Fig. 5B of Wiese et al. [26]). Bending or looping models do not rule out the possibility of direct RNAP-IHF contacts occurring as well [32].

Does Crp pre-position RNAP in response to energy metabolism?

The flux through the GlnA/GltBD pathway can be quite high in minimal media. ATP is required for the GlnA/GltBD pathway and not for the GdhA pathway (Fig. 1), and governing the relative fluxes through these alternative pathways is probably one of the most critical regulatory problems faced by E. coli. We report direct regulation of PgltB by Crp, in agreement with earlier indirect evidence [15]. A microarray-based global analysis of E. coli genes affected by Crp [33] did not identify the gltBDF operon, but this probably reflects the rich culture medium (LB) used in that work. Crp is broadly associated with the control of carbon and energy source utilization, usually activating genes for utilization of less-efficient carbon/energy sources (relative to glucose) [33]. Competitions between gdhA and gdhA+ strains [3,4] reveal a clear advantage for the gdhA+ strain during glucose limitation, suggesting that Crp modulates the relative activities of the two alternative pathways for glutamate synthesis to favor the ATP-independent pathway during growth on suboptimal carbon sources [3,4]. The reciprocal effects of carbon source and addition of cAMP on GdhA and GltBD activities are consistent with just this role for Crp [15]. In addition, Crp-cAMP represses one of the promoters for the glutamine synthetase gene (glnAp2) [34], so both enzymes for the GlnA/GltBD pathway are controlled in parallel by Crp.

Our data show that Crp-cAMP binding in vitro (Fig. 5B, E) is correlated with reduced transcription in vivo (Fig. 6), and that RNAP generates a protection pattern at PgltB in the presence of Crp-cAMP (Fig. 7, lane 7) different from the pattern yielded by RNAP in the presence of IHF + Lrp (Fig. 3B, lane 7). The Crp-cAMP repression thus appears to alter RNAP binding rather than blocking it. The Crp footprint is centered at -65.5 relative to the start of gltB transcription, close to the position from which Crp activates class I promoters [35] where Crp binds between the C-terminal domain of RpoA (αCTD) and region 4 of RpoD (σ70). However optimal spacing from the proximal edge of the Crp binding site to that of the -35 hexamer is 13–16 bp in class I promoters, while in PgltB this spacing is 21 bp (Fig. 2A). Crp may thus repress PgltB by mispositioning or trapping RNAP. Repression has been seen due to mispositioning of RNAP via alternative binding sites [36], or trapping at the promoter [37,38]. A recent global analysis suggests that nearly a quarter of σ70 (RpoD)-dependent promoters have bound RNAP that is "poised" but not transcribing [39]. RNAP poised at PgltB would allow a rapid increase of GltBD levels in the face of falling ammonium concentrations, as the GdhA reaction becomes increasingly inefficient (Fig. 1).

Role of ArgR in repressing gltBDF

As shown in Fig. 1, glutamate is a precursor of ornithine, which in turn is converted to arginine. Thus regulation of GltBD in response to arginine is an example of negative feedback regulation. The relatively modest effects are appropriate given the need for glutamate in many other pathways. A similar feedback regulation of glutamate biosynthesis by ArgR was recently observed in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [40]. The mechanism by which ArgR represses PgltB is not clear, but our evidence is consistent with the possibility that ArgR interferes with formation of the final activation complex. As shown in Fig. 8, and illustrated in Fig. 2, ArgR binds far upstream of the promoter, near the Lrp-binding region. However ArgR does not appear to have a major effect on Lrp binding (Fig. 9A). Our working hypothesis is that ArgR allows pre-assembly of the Lrp-IHF-RNAP complex, but blocks a specific contact required for transcriptional activation. This would resemble the suggested role of Crp (see above) in reducing gltBD expression while allowing rapid return to full activation should the appropriate conditions change.

Role of Lrp in regulation of gltBD

Lrp is not simply a signal of amino acid sufficiency. First, gltBDF is one of the operons for which Lrp regulation is relatively insensitive to the coregulator leucine [5,28]. Second, Lrp levels (like those of the coactivator IHF [41]) are sensitive to the alarmone ppGpp [42], which in turn is affected by sufficiency of both amino acids and other nutrients [43]. Lrp levels vary between media, and (like those of the coactivator IHF [41]) also through the growth cycle [42].

Much of what is known about regulation of GdhA, GlnA, and GltBD is consistent with the expected reciprocal pattern between the two pathways shown in Fig. 1. One would expect GdhA levels to parallel those of [NH4+], while GlnA and GltBD levels would perhaps follow the inverse of [NH4+] and parallel those of ATP. In fact, gdhA is repressed by Nac, with repression relieved in high [NH4+], while neither glnA nor gltBD appear to respond substantially to Nac [17,44,45]. Similarly, transcription of both glnA and gltBD is repressed by Crp-cAMP while effects on gdhA are unclear (this work, [34,46]). Conversely, both GlnA activity (indirectly, via glnL) and gltBD transcription are boosted by Lrp, which has no obvious effect on gdhA [5,6,28].

Modeling analysis [47] suggests that the major control of relative flux between the alternative pathways shown in Fig. 1 should involve regulation of GlnA activity (via adenylylation and deadenylylation [48]). Lrp has major effects on GlnA expression and adenylylation status in response to ammonia levels [2,5,7]. The effect of Lrp on GlnA expression and activity is indirect, probably involving the direct Lrp effect on GltBD expression that, in turn, modulates the intracellular ratios of α-ketoglutarate, glutamate, and glutamine [49]. This model requires changes in gene expression levels for adaptation to sudden large changes in [NH4+], with gltBD needing to be expressed above a threshold level. The 30-40-fold activation of PgltB by Lrp [28] is consistent with a major switch above or below this critical threshold expression level. In contrast, the effects of Crp and ArgR (and of leucine, in this case) are smaller, fine-tuning controls that may modulate the flow of glutamine out of the middle of the GlnA-GltBD pathway.

Conclusion

Results from this study demonstrate that the physiologically-important gltBDF operon of E. coli is subject to negative as well as positive control, and involves a third member of the group of seven most-global transcriptional regulatory proteins. In addition to the previously-demonstrated direct positive roles of Lrp and IHF, there are direct negative roles for Crp and ArgR. Lrp and IHF appear to stabilize RNAP binding to the promoter, as no RNAP-dependent footprint appears unless both Lrp and IHF are present. Crp-cAMP can replace Lrp + IHF in potentiating footprint formation by RNAP, though the resulting protection patterns are distinct. ArgR alters, but does not prevent, footprint formation by RNAP + Lrp + IHF. It does not appear that either repressor, Crp or ArgR, acts by interfering with binding of the activators or of RNAP. This study does not explore the specific mechanisms of activation or repression at gltBDF, but the results are consistent with the possibility that Crp and ArgR inhibit transcription in such a way as to leave the RNAP poised for rapid transcription initiation when conditions require it. Given the central importance of the regulation of glutamate biosynthesis, reflected by the involvement of Lrp and two other E. coli global regulatory proteins, it would be instructive to know whether this regulatory mechanism is broadly conserved among related bacterial species adapted to different nutritional environments.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids and culture conditions

The strains, plasmids and PCR primers used in this study are listed in Table 2. All strains were derivatives of E. coli K-12 W3110 or LP2002 (in which the rph mutation of W3110 was corrected; see below). For β-galactosidase assays, strains were grown in glucose minimal MOPS medium [50,51] containing ampicillin (20 μg/ml for chromosomal and 80 μg/ml for plasmid-borne resistance) or 7.5 mM L-arginine HCl (Sigma) where indicated. Cultures grown to test the effects of Crp-binding site mutations were grown in MOPS defined-rich medium (Teknova, Hollister, CA) containing 100 μg ampicillin per ml and 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG), in the presence or absence of 10 μM dibutyryl-cAMP (BioMol Research Labs, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Plates for most genetic work used agar containing "LB" medium [52].

Construction of the rph+ strain LP2002 and its derivatives

The widely used E. coli K-12 strain W3110 contains a frameshift mutation in rph associated with decreased levels of the pyrE product orotate phosphoribosyltransferase [29]. This frameshift was corrected as follows. A 790 bp fragment of rph and downstream sequence was amplified from W3110 chromosomal DNA using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the overlap extension procedure [53]. The primers used were rph1-4 (Table 2). Primers rph2 and rph3 contain the additional base pair required to correct the frame shift in the rph gene (underlined italic in Table 2). The PCR product was cloned into E. coli strain XL-1Blue (Stratagene) using the pGEMT-easy vector (Promega). The insert was then excised with NotI and ligated into NotI-digested suicide vector pKO3 [54]. Electrocompetent W3110 cells were transformed with pKO3 carrying the modified rph gene, and integrants were selected at 43°C. Cells that had lost the plasmid were isolated by plating on LB agar containing 5% sucrose, which selects against the plasmid sacB gene [54]. Colonies from LB-sucrose plates were replica plated onto unsupplemented LB and LB-chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml). Colonies that grew on LB plates but not on LB-chloramphenicol were screened for correction of the frame shift in the rph gene by amplifying the rph region by PCR and sequencing the product. The resulting rph+ strain was designated LP2002.

The lac operon was deleted from strain LP2002 using the overlap extension protocol [53] with primers lac6-9 (Table 2). The lac6 primer corresponds to nucleotides 814 to 842 within the coding region of lacI; the lac7 primer is complementary to the 5' region of primer lac8; the 3' end of lac8 bridges the deletion region (see below), and lac9 corresponds to nucleotides 1019 to 1044 of the coding region of cynX gene downstream of the lacZYA operon. The final amplified product has a deletion starting immediately upstream of the -10 region of the lacZYA operon and extending to the 3' end of the lacA gene, leaving the last 19 codons of lacA intact. This product was introduced into the chromosome of LP2002 using the suicide vector pKO3 [54]. The ΔlacZYA recombinants were identified as white colonies on LB-Xgal plates, and the deletion was verified by amplifying the chromosomal lac region and sequencing the fragment. The resultant strain was designated LP2010. The gltB-lacZ transcriptional fusion from LP1000 [14,55] was introduced into LP2010 via P1 transduction [55] and designated LP2020.

Construction of ΔargR strains

A portion of argR was deleted from strains LP1000 and LP2020 as follows. The argR gene from strain PS2209 (W3110 Δlac-169 from F. C. Neidhardt) was amplified from chromosomal DNA by PCR, using the primers arg1 and arg2 (Table 2). The amplified product was ligated into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega). The argR fragment was excised from the vector with NotI, and the region of argR coding for amino acids 15–90 were deleted in-frame by removing a DraI/EcoRV fragment from the argR gene and religating the blunt ends. This fragment was ligated into suicide vector pKO3 [54] and introduced into strains LP1000 and LP2020. Prospective mutants were screened by amplifying the argR region from their genomic DNA; the amplified fragment was shorter in the deletion mutants. The ΔargR strains were designated LP1050 (LP1000 derivative) and LP2023 (LP2020 derivative).

CipherGen ProteinChip™ assays

Surface-enhanced laser desorption and ionization (SELDI) ProteinChip technology (Ciphergen Biosystems, currently distributed by BioRad, Hercules, CA) was used to identify proteins binding to the upstream region of the gltBDF operon. In this approach, biotin-labeled gltB DNA (from -406 to +246) was attached to streptavidin-coated chips and incubated with centrifugally-cleared whole-cell extracts. The masses of proteins that bound to the DNA fragments were determined using SELDI mass spectroscopy. This binding experiment was carried out under nonstringent conditions so as to detect relatively weak binding interactions. E. coli cells (strain W3110) were grown in glucose minimal MOPS medium and opened using glass beads in a BeadBeater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK). PS-1 (carbonyl diimidazole) ProteinChips were coated with streptavidin (Pierce, Immunopure™) at 0.2 microgram/spot, washed, and the unbound sites were blocked with 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.0). The DNA, generated by PCR using biotinylated primers, was first bound to the streptavidin on the chip, and then incubated with cell extract in 20 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.0), 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 250 mM NaCl, 4 mM Mg acetate, 12.5% glycerol (v:v), and 200 μg/ml of salmon sperm DNA (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, N.J.). The chips were washed with 20 mM Tris-acetate containing 0.1% Triton X-100. The matrix EAM-1 (Ciphergen) was added to the chip prior to SELDI mass analysis.

Expression and purification of Lrp, ArgR, Crp and IHF

In all cases, protein purity was assessed from single (or, in the case of IHF, double) Coomassie-stained bands when μg amounts were loaded onto SDS polyacrylamide gels. Lrp was purified from strain JWD3 and isolated as previously described [28]. The genes argR, crp, himA and himD (the latter two coding for IHF subunits) were amplified from strain W3110 chromosomal DNA. The argR gene was amplified using primers arg3 and arg4 (Table 2), cloned into the expression vector pET23b (Novagen) at the NdeI/XhoI sites creating pLP1060, and introduced into the expression host BL21(DE3) (Novagen) which carries an inducible gene for T7 RNAP. The protein was purified from the resulting strain LP1060, as described by Sunnerhagen et al. [56].

The crp gene was amplified using primers crp5 and crp6 (Table 2), ligated into the NdeI/XhoI sites of expression vector pET29a (Novagen) to create pLP1070, and introduced into strain BL21(DE3) resulting in strain LP1070. The overexpressed protein was purified using a nickel affinity column (Pharmacia) since the wild type Crp (without a his-tag) binds nickel columns with moderate affinity [57].

The genes himA and himD were amplified from W3110 chromosomal DNA using primers himA1 and himA2 and primers himD1 and himD2 (Table 2). The amplified products were ligated in tandem into the expression vector pET28a (Novagen) at the NcoI/BamHI sites to create pLP1080, and introduced into strain BL21(DE3). The strain was designated LP1080. IHF with an N-terminal histidine tag on HimA was purified using a 3 ml Hi-Trap Heparin Sepharose column from Pharmacia [58].

Construction of PgltB-lacZ fusion and variant with altered Crp-binding site

The promoter region upstream of gltB was amplified from E. coli chromosomal DNA using primers gltP1-2 (Table 2), and the resulting PCR product was digested with BamHI and SalI. This product was ligated into pBH403, a derivative of pKK232-8 with a promoterless lacZ gene between two bidirectional transcription terminators, to generate pPM2005 (Table 2). This process was repeated with a mutagenic primer pair (gltcrp1-2, Table 2) to generate pPM2006, which has alterations within the Crp-binding site in the glt promoter. Plasmids were sequence confirmed and used to transform the ΔlacZ W3110 derivative PS2209.

β-galactosidase assays

Cultures were grown to exponential phase in the indicated media. Samples were taken at 30-min intervals throughout the growth period. Levels of β-galactosidase were determined by o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactoside (ONPG) hydrolysis as described by Platko et al. [59]. β-galactosidase levels were plotted against culture absorbance, and points were fitted via linear regression. The resulting slope yields the β-galactosidase acitivity.

Mobility shift and DNase I protection assays

RNA polymerase holoenzyme was purchased from Epicentre Biotechnologies (Madison, WI). Assays were carried out as described in Paul et al. [14] except where indicated. In electrophoretic mobility shift experiments involving ArgR, the reaction mixture and the polyacrylamide gel both contained 5 mM L-arginine, and the running buffer (1 × TBE [90 mM Tris borate, pH 8.3, 0.2 mM EDTA]) contained 1 mM L-arginine. Crp-DNA binding was carried out in a buffer modified from Seoh and Tai [60] containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, 50 μg/ml BSA, 10 μg/ml poly (dI-dC):poly(dI-dC) from Pharmacia and 12.5% glycerol. cAMP (20 mM, Sigma) was added to the reaction buffer, the gel and the running buffer (0.5 × TBE). The buffer for DNase I protection assays (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 50 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml and 2 μg of poly(dI-dC):poly(dI-dC)/ml) contained 5 mM L-arginine or 20 mM cAMP for reactions involving ArgR and Crp respectively.

Authors' contributions

LP carried out most of the laboratory experiments, with PM responsible for those involving alteration of the Crp binding sites and tests of their function. LP, RB and RM planned the experiments and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, with RB having primary responsibility for the writing and the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank George M. Church of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, for the plasmid pKO3, Ruth Van Bogelen of Pfizer Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, for help with the SELDI analysis, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. This project was supported in part by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation to RGM and RMB (MCB-9807237), and by a grant to RMB from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (AI054716).

Contributor Information

Ligi Paul, Email: Ligi.Paul_Pottenplackel@tufts.edu.

Pankaj K Mishra, Email: Pankaj.Mishra@utoledo.edu.

Robert M Blumenthal, Email: Robert.Blumenthal@utoledo.edu.

Rowena G Matthews, Email: RMatthew@umich.edu.

References

- Martinez-Antonio A, Collado-Vides J. Identifying global regulators in transcriptional regulatory networks in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzer L. Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:155–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helling RB. Pathway choice in glutamate synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4571–4575. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4571-4575.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helling RB. Why does Escherichia coli have two primary pathways for synthesis of glutamate? J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4664–4668. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4664-4668.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernsting BR., Atkinson, M. R., Ninfa, A. J. and Matthews, R. G. Characterization of the regulon controlled by the leucine responsive regulatory protein. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1109–1118. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1109-1118.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani TH., A. Khodursky, R. M. Blumenthal, P. O. Brown and R. G. Matthews Adapation to famine: a family of stationary-phase genes revealed by microarray analysis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13471–13476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212510999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo JM, Matthews RG. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein, a global regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:466–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.466-490.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinser ER, Kolter R. Prolonged stationary-phase incubation selects for lrp mutations in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4361–4365. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.15.4361-4365.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colland F, Barth M, Hengge-Aronis R, Kolb A. Sigma factor selectivity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: role for CRP, IHF and Lrp transcription factors. EMBO J. 2000;19:3028–3037. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Azam T, Iwata A, Nishimura A, Ueda S, Ishihama A. Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6361–6370. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6361-6370.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier J, Gordia S, Kampmann G, Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R, Gutierrez C. Interplay between global regulators of Escherichia coli: effect of RpoS, Lrp and H-NS on transcription of the gene osmC. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:971–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landini P, Hajec LI, Nguyen LH, Burgess RR, Volkert MR. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp) acts as a specific repressor for sigmaS-dependent transcription of the Escherichia coli aidB gene. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:947–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinthal M, Pownder T. Hns, RpoS and Lrp mutations affect stationary-phase survival at high osmolarity. Res Microbiol. 1996;147:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)84708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul L., R. M. Blumenthal and R. G. Matthews Activation from a distance: Roles of Lrp and integration host factor in transcriptional activation of gltBDF. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3910–3918. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3910-3918.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner S., R. E. Miller and R. C. Valentine Adenosine 3':5'-cyclic monophosphate control of the enzymes of glutamine metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:2922–2926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.10.2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinidou C, Hobman JL, Griffiths L, Patel MD, Penn CW, Cole JA, Overton TW. A reassessment of the FNR regulon and transcriptomic analysis of the effects of nitrate, nitrite, NarXL, and NarQP as Escherichia coli K12 adapts from aerobic to anaerobic growth. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4802–4815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer DP, Soupene E, Lee HL, Wendisch VF, Khodursky AB, Peter BJ, Bender RA, Kustu S. Nitrogen regulatory protein C-controlled genes of Escherichia coli: scavenging as a defense against nitrogen limitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14674–14679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommais F, Krin E, Coppee JY, Lacroix C, Yeramian E, Danchin A, Bertin P. GadE (YhiE): a novel activator involved in the response to acid environment in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2004;150:61–72. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keseler IM, Collado-Vides J, Gama-Castro S, Ingraham J, Paley S, Paulsen IT, Peralta-Gil M, Karp PD. EcoCyc: a comprehensive database resource for Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D334–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ari R, Jaffe A, Bouloc P, Robin A. Cyclic AMP and cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:65–70. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.65-70.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magasanik B. Global regulation of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14044–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogema BM, Arents JC, Inada T, Aiba H, van Dam K, Postma PW. Catabolite repression by glucose 6-phosphate, gluconate and lactose in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:857–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3991761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SH, Lee JC. Determinants of DNA bending in the DNA-cyclic AMP receptor protein complexes in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4809–4818. doi: 10.1021/bi027259+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier D., M. Roovers, F. van Vilet, A. Boyen, R. Cunin, Y. Nakamura, N. Glansdorff and A. Pierard The arginine regulon of Escherichia coli K12: A study of repressor-operator interactions and of in vitro binding affinities versus in vivo repression. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:367–386. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90953-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G., D. Lim, J. Carey, and W. K. Maas Binding of the arginine repressor of Escherichia coli K12 to its operator sites. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:387–397. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90954-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese DE, 2nd, Ernsting BR, Blumenthal RM, Matthews RG. A nucleoprotein activation complex between the leucine-responsive regulatory protein and DNA upstream of the gltBDF operon in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1997;270:152–168. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JN. The Hill equation revisited: uses and misuses. FASEB J. 1997;11:835–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernsting BR., J. W. Denninger, R. M. Blumenthal and R. G. Matthews Regulation of gltBDF operon of Escherichia coli: How a leucine-insensitive operon is regulated by leucine-responsive regulatory protein. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7160–7169. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7160-7169.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KF. The Esherichica coli K-12 "wild types" W3110 and MG1655 have an rph frameshift mutation that leads to pyrimidine starvation due to low pyrE expression levels. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3401–3407. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3401-3407.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinger KK, Rice PA. IHF and HU: flexible architects of bent DNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh BS, Sheridan SD, Hatfield GW. Effects of integration host factor and DNA supercoiling on transcription from the ilvPG promoter of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20258–20264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giladi H, Koby S, Prag G, Engelhorn M, Geiselmann J, Oppenheim AB. Participation of IHF and a distant UP element in the stimulation of the phage lambda PL promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:443–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosset G, Zhang Z, Nayyar S, Cuevas WA, Saier MH., Jr. Transcriptome analysis of Crp-dependent catabolite control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3516–3524. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3516-3524.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian ZX, Li QS, Buck M, Kolb A, Wang YP. The CRP-cAMP complex and downregulation of the glnAp2 promoter provides a novel regulatory linkage between carbon metabolism and nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:911–924. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savery NJ, Lloyd GS, Busby SJ, Thomas MS, Ebright RH, Gourse RL. Determinants of the C-terminal domain of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit important for transcription at class I cyclic AMP receptor protein-dependent promoters. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2273–2280. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.8.2273-2280.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami H, Aiba H. An inactive open complex mediated by an UP element at Escherichia coli promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7202–7207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder O, Wagner R. The bacterial DNA-binding protein H-NS represses ribosomal RNA transcription by trapping RNA polymerase in the initiation complex. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:737–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Garges S, Adhya S. lacP1 promoter with an extended -10 motif. Pleiotropic effects of cyclic AMP protein at different steps of transcription initiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54552–54557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppas NB, Wade JT, Church GM, Struhl K. The transition between transcriptional initiation and elongation in E. coli is highly variable and often rate limiting. Molec Cell. 2006;24:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashim S., D. H. Kwon, A. Abdelal and C. D. Lu The arginine regulatory protein mediates repression by arginine of the operons encoding glutamate synthase and anabolic glutamate dehydrogenase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3848–3854. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3848-3854.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv M, Giladi H, Schreiber G, Oppenheim AB, Glaser G. Expression of the genes coding for the Escherichia coli integration host factor are controlled by growth phase, rpoS, ppGpp and by autoregulation. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:1021–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf JR, Wu J, Calvo JM. Effects of nutrition and growth rate on Lrp levels in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6930–6936. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6930-6936.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson LU, Farewell A, Nystrom T. ppGpp: a global regulator in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarena L, Poggio S, Garcia N, Osorio A. Transcriptional repression of gdhA in Escherichia coli is mediated by the Nac protein. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;167:51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse WB, Bender RA. The nac (nitrogen assimilation control) gene from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1166–1173. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1166-1173.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D, Constantinidou C, Hobman JL, Minchin SD. Identification of the CRP regulon using in vitro and in vivo transcriptional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5874–5893. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman FJ, Boogerd FC, Westerhoff HV. The multifarious short-term regulation of ammonium assimilation of Escherichia coli: dissection using an in silico replica. FEBS J. 2005;272:1965–1985. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggi R, van Heeswijk WC, Westerhoff HV, Ollis DL, Vasudevan SG. The two opposing activities of adenylyl transferase reside in distinct homologous domains, with intramolecular signal transduction. EMBO J. 1997;16:5562–5571. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Peliska JA, Ninfa AJ. The regulation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase revisited: role of 2-ketoglutarate in the regulation of glutamine synthetase adenylylation state. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12802–12810. doi: 10.1021/bi980666u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhardt FC., P. L. Bloch, and D. F. Smith Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis . Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY. , Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bertani G. Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:595–600. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.595-600.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L., and P. Rudolph Simultaneous introduction of multiple mutations using overlap extension PCR. Biotechniques. 1997;22:28–30. doi: 10.2144/97221bm03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link AJ., Phillips, D. and Church, G.M. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: Application to open reading frame characterization. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6228–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6228-6237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold spring harbor, N. Y. , Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Sunnerhagen M., M. Nilges, G. Otting, and J. Carey Solution structure of the DNA-binding domain and model for the complex of mutlifunctional hexameric arginine repressor with DNA. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:819–825. doi: 10.1038/nsb1097-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickstrum JR., and S. M. Egan Ni+-Affinity purification of untagged cAMP receptor protein. Biotechniques. 2002;33:728–730. doi: 10.2144/02334bm01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filutowicz M., H. Grimek, and K. Appelt Purification of Escherichia coli integration host factor (IHF) in one chromatographic step. Gene. 1994;147:149–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platko JV., D. A. Willins, and J. M. Calvo The ilvIH operon of Escherichia coli is positively regulated. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4563–4570. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4563-4570.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoh HK., and P. C. Tai Catabolic repression of secB expression is positively controlled by cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein-cAMP complexes at the transcriptional level. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1892–1899. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1892-1899.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosius J. Plasmid vectors for the selection of promoters. Gene. 1984;27:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowle D, Lintner RE, Touma YM, Blumenthal RM. Nature of the promoter activated by C.PvuII, an unusual regulatory protein conserved among restriction-modification systems. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:488–497. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.488-497.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BioCyc http://biocyc.org/ECOLI/

- Makarova KS, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS. Conservation of the binding site for the arginine repressor in all bacterial lineages. Genome Biol. 2001;2:RESEARCH0013. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-4-research0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]