Abstract

Background

For patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), it is often assumed by treating physicians that the severity of heartburn correlates with the severity of erosive esophagitis (EE).

Objective

This is a post hoc analysis of data from 5 clinical trials that investigate the relationship between the baseline severity of heartburn and the baseline severity of EE.

Methods

Patients with endoscopically confirmed EE were assessed for heartburn symptoms with a 4-point scale at baseline and during treatment for 8 weeks with various proton pump inhibitors in 5 double-blind trials in which esomeprazole was the common comparator. EE was graded with the Los Angeles (LA) classification system. In these trials, healing and symptom response were evaluated by endoscopy and questionnaire after 4 weeks of treatment. Patients who were not healed were treated for an additional 4 weeks and reevaluated.

Results

A total of 11,945 patients with endoscopically confirmed EE participated in the 5 trials, with patients receiving esomeprazole 40 mg (n = 5068), esomeprazole 20 mg (n = 1243), omeprazole 20 mg (n = 3018), or lansoprazole 30 mg (n = 2616). Approximately one quarter of the 11,945 GERD patients in these 5 trials had severe EE (defined as LA grades C or D), regardless of their baseline heartburn severity.

Conclusion

The severity of GERD symptoms does not correlate well with disease severity. These findings indicate that endoscopy may have value in GERD patients in identifying those with EE, and if empirical therapy is chosen, then longer courses (4-8 weeks) of antisecretory therapy may be necessary to ensure healing of unrecognized esophagitis.

Readers are encouraged to respond to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Introduction

An estimated 19 million adults in the United States regularly experience the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD),[1] and 55% to 65% of patients with GERD symptoms who were screened for enrollment in prospective US studies evaluating treatments for erosive esophagitis (EE) were found to have EE when examined endoscopically.[2,3] GERD is a chronic illness that negatively affects the physical, psychological, emotional, and social domains of health[4] and that is characterized by a complex of acid-related symptoms, including heartburn, dysphagia, epigastric pain, and acid regurgitation. The international, multidisciplinary, evidence-based Genval Workshop on the management of GERD recognized the negative impact of GERD on health-related quality of life by incorporating this concern into the definition of GERD.[5] Participants at the workshop defined GERD by the presence of mucosal breaks on endoscopy (EE) or by the presence of reflux-associated symptoms that are severe enough to reduce quality of life.[5]

This definition acknowledges that endoscopic diagnosis of EE, although routinely used in clinical trials, is less practical in clinical practice. Initial therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), the agent of choice for the treatment of GERD, is often initiated empirically in patients presenting with symptoms of uncomplicated GERD.[6] Therefore, it would be useful to know whether the severity of heartburn correlates with the severity of disease because endoscopic examination is typically reserved for GERD patients with chronic symptoms (screening for Barrett's esophagus in patients at risk) or in those exhibiting alarm symptoms.[5,6] For most disease states, an increase in disease severity is generally accompanied by more severe symptoms. Unfortunately, the severity of symptoms may not provide a reliable index of the severity of disease in patients with GERD.

The clinical trial program for esomeprazole prospectively evaluated nearly 12,000 patients with endoscopically verified EE. The aim of this post hoc analysis was to investigate the relationship between the baseline severity of heartburn and the baseline severity of EE in this large group of patients with EE, with the available symptom and endoscopic data from these near-identical and well-characterized clinical trials.

Patients and Methods

Patients with endoscopically confirmed EE, graded from A to D by the Los Angeles (LA) classification system,[7] participated in 5 separate, randomized, controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy of esomeprazole, compared with lansoprazole or omeprazole, for the healing of EE and resolution of symptoms of GERD. Detailed descriptions of the study protocol and the results of these trials have been reported elsewhere.[8–11] In each of these 5 trials, patients were treated in a double-blind manner for 8 weeks with PPI therapy (esomeprazole 40 mg, esomeprazole 20 mg, omeprazole 20 mg, or lansoprazole 30 mg), in which esomeprazole was the common comparator. Healing was evaluated by endoscopy after 4 weeks of treatment. Patients who were not healed were treated for an additional 4 weeks and reevaluated by endoscopy. Institutional review boards at all participating centers approved all aspects of the clinical trial protocols, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Patient Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Men and nonpregnant, nonlactating women 18 years or older with endoscopically verified EE (LA grades A-D) were eligible for enrollment in these trials. Patients were excluded if they had a bleeding disorder or signs of gastrointestinal bleeding at the screening endoscopy or 3 days before randomization to the study. Other exclusion criteria included Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, esophageal stricture, Barrett's esophagus (> 3 cm), evidence of upper gastrointestinal malignancy, or other severe concomitant disease involving any organ system. Exclusion that was based on medication use included PPI therapy within the 28-day period before baseline visit, daily H2-receptor antagonist use during the 2 weeks before baseline endoscopy (occasional, less frequent than daily use was permitted), and the need for continuous concurrent therapy or treatment within 1 week of randomization with prostaglandin analogs, antineoplastic agents, salicylates (unless < 165 mg daily for cardiovascular prophylaxis), steroids, promotility drugs, sucralfate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or any other medications that might confound study results.

Heartburn Assessment

Heartburn was defined as a burning feeling emanating from the stomach or lower part of the chest and radiating toward the neck. At baseline and at the end of week 4, the clinical investigator evaluated the presence and severity of heartburn with a 4-point scale. Heartburn could be described as absent, mild (awareness of symptom, but easily tolerated), moderate (discomfort sufficient enough to cause interference with normal activities, including sleep), or severe (incapacitating, with inability to perform normal activities, including sleep).

Heartburn data were collected during the first 4 weeks of each study. Patients were instructed to take medication before breakfast and to record the presence or absence of heartburn in a daily diary. Patients were provided antacids as a symptom “rescue” medication.

Statistical Analysis

The SAS statistical software package was used to conduct the statistical analyses. The relationship between baseline severity of heartburn and baseline severity of EE (mild = LA grade A, B; severe = LA grade C, D) was analyzed with the Mantel-Haenszel correlation test statistic. The odds ratio, together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), also was used to assess the relationship between the status of heartburn at baseline (as present or absent) and the severity of EE at baseline.

The relationship of healing rates to the resolution or persistence of heartburn was examined for those patients with heartburn present at baseline. Only data from patients whose final endoscopic and heartburn assessments were conducted on the same day were included. The effect of baseline heartburn severity on the healing rates was assessed with the Mantel-Haenszel correlation statistic. The odds ratio, together with 95% CIs, also was used to assess the relationship between heartburn status (resolution or persistence) and the healing status.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 11,945 patients with endoscopically confirmed EE participated in the 5 trials, with patients receiving esomeprazole 40 mg (n = 5068), esomeprazole 20 mg (n = 1243), omeprazole 20 mg (n = 3018), or lansoprazole 30 mg (n = 2616). Overall, patients in each treatment group had similar demographic and disease characteristics at baseline (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Other Baseline Characteristics of Patients Included in This Meta-analysis

| Esomeprazole 40 mg (n = 5068) | Esomeprazole 20 mg (n = 1243) | Omeprazole 20 mg (n = 3018) | Lansoprazole 30 mg (n = 2616) | Total (n = 11,945) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | Men | 2955 (58) | 763 (61) | 1869 (62) | 1501 (57) | 7088 (59) |

| Women | 2113 (42) | 480 (39) | 1149 (38) | 1115 (43) | 4857 (41) | |

| Age, years | Mean (SD) | 46.6 (13) | 45.0 (13) | 46.3 (13) | 47.4 (13) | 46.4 (13) |

| LA grade, n (%) | A | 1811 (36) | 440 (35) | 990 (33) | 916 (35) | 4157 (35) |

| B | 1945 (38) | 480 (39) | 1203 (40) | 1054 (40) | 4682 (39) | |

| C | 1002 (20) | 240 (19) | 606 (20) | 477 (18) | 2325 (19) | |

| D | 310 (6) | 83 (7) | 219 (7) | 169 (6) | 781 (6.5) | |

| GERD duration, n (%) | < 1 year | 332 (7) | 2 (5) | 178 (6) | 204 (8) | 776 (6.5) |

| 1-5 years | 2171 (43) | 576 (46) | 1290 (43) | 1090 (42) | 5127 (43) | |

| > 5 years | 2564 (51) | 605 (49) | 1550 (51) | 1322 (51) | 6041 (50) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.02) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.01) | |

| Heartburn severity, n (%) | None | 74 (1) | 26 (2) | 55 (2) | 20 (2) | 175 (1) |

| Mild | 502 (10) | 110 (9) | 333 (11) | 290 (11) | 1235 (10) | |

| Moderate | 2362 (47) | 615 (49) | 1435 (48) | 1209 (46) | 5621 (47) | |

| Severe | 2128 (42) | 492 (40) | 1192 (39) | 1097 (42) | 4909 (41) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.04) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.02) |

LA = Los Angeles classification system; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease

Heartburn Severity

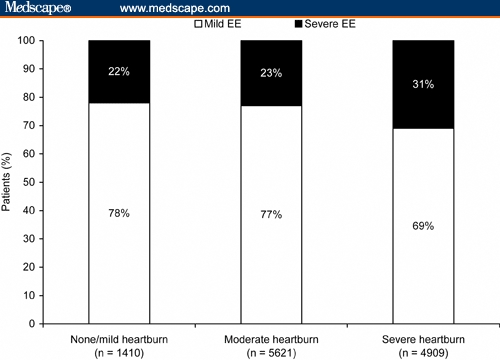

Heartburn at baseline was reported by almost 99% of patients (Table 1). Heartburn was mild in 10% of patients for whom complete data were available, moderate in 47% of patients, and severe in 41% of patients. Because there were few patients without symptoms of heartburn, data for patients in the none and mild heartburn categories were combined for further analysis. Severe EE was present in 31% of patients with severe heartburn at baseline, compared with 23% of patients with moderate heartburn and 22% of patients with none or mild heartburn (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Severe erosive esophagitis (EE; Los Angeles grades C and D) was observed in a similar percentage of patients, regardless of the baseline severity of heartburn. The observed rates of 22% to 31% mean that 25% of patients had moderate-to-severe EE, regardless of their heartburn status (odds ratio, 1.2; 95% confidence interval, 0.8-1.7).

Resolution of Heartburn

Sixty percent of patients had investigator-assessed complete resolution of heartburn by week 4 of PPI therapy. Esomeprazole 40 mg resolved heartburn symptoms in 62.3% of recipients, vs 58.8% for esomeprazole 20 mg, 57.5% for omeprazole 20 mg, and 58.0% for lansoprazole 30 mg.

Healing of EE and Resolution of Heartburn

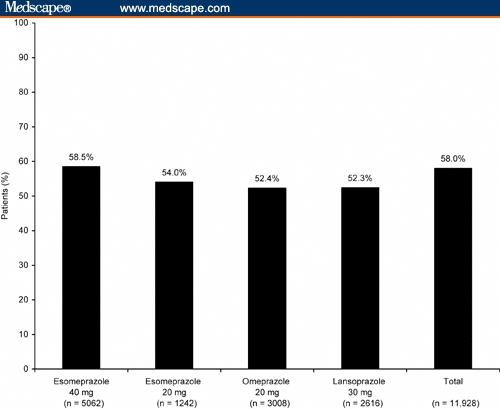

In all 5 clinical trials, there was a relatively high concurrence across all treatment groups between healing of EE at week 4 and resolution of heartburn (odds ratio, 3.6; 95% CI, 3.2-4.0). Healed EE and resolution of heartburn at week 4 were reported for 52% to 58% of patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients with both healed erosive esophagitis and resolution of heartburn symptoms after 4 weeks of treatment.

Among all of the patients treated with PPI therapy, 91.5% of those with resolution of heartburn by week 4 also had healing of EE (91.7% esomeprazole 40 mg, 90.6% esomeprazole 20 mg, 91.6% omeprazole 20 mg, and 91.3% lansoprazole 30 mg). On the other hand, 24% of patients with continuing heartburn symptoms did not have EE healing. The investigator-assessed severity of heartburn at week 4 also was a good predictor of healing status, with healing rates of 82.8%, 63.3%, and 45.1% observed for patients with mild, moderate, and severe heartburn, respectively.

Discussion

Heartburn commonly occurs in patients across all grades of underlying EE. The presence of heartburn does not provide a reliable clinical indication of the presence or severity of EE. Approximately one quarter of the 11,945 GERD patients in these 5 clinical trials had severe (LA grades C or D) EE, regardless of their baseline heartburn severity. Therefore, the severity of heartburn cannot be used to predict the severity of EE. Although we found some statistically significant associations in the analyses presented here, the actual magnitude of the between-group differences was small and unlikely to be of clinical relevance.

These results have an impact on clinical practice in which, in contrast to clinical trials, endoscopic determination of the severity of EE is less likely to be routine for patients with uncomplicated GERD. Heartburn is the most common GERD-associated symptom, and it occurred in almost all patients enrolled in the 5 clinical trials included in our analysis. Recent guidelines for the management of GERD confirm that sustained freedom from heartburn is indicative of healing of esophageal lesions.[5,6] In agreement with these findings, resolution of heartburn in our analysis was predictive of healing of EE.

Conclusion

If choosing empirical therapy, the primary care physician should consider the potential to optimize outcomes across all grades of EE. Current clinical management guidelines for patients with GERD recommend that the most effective treatment should be initiated as early as possible.[5,6,12] Because the severity of GERD symptoms does not correlate well with disease severity, treatment with acid-suppressive therapy that produces symptom resolution should be the primary consideration for empirically managing patients with GERD, and a course of therapy of sufficient duration to heal unrecognized esophagitis should be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Caroline Spencer and Carol Lewis from Wolters Kluwer Health, Yardley, Pennsylvania, and Adis International, Yardley, Pennsylvania, and Gabriel Salameh and Judy Fallon from Thomson Scientific Connexions, Newtown, Pennsylvania, who provided medical writing support on behalf of AstraZeneca LP, Wilmington, Delaware; Mary Wiggin from AstraZeneca LP for editing assistance; and Barry Traxler from AstraZeneca LP for performing the statistical analysis.

Funding Information

This study has been funded by AstraZeneca. Medical writing support has been provided by Wolters Kluwer Health, Yardley, Pennsylvania; Adis International, Yardley, Pennsylvania; and Thomson Scientific Connexions, Newtown, Pennsylvania on behalf of AstraZeneca LP, Wilmington, Delaware.

Contributor Information

M. Brian Fennerty, Division of Gastroenterology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon. Email: fennerty@ohsu.edu.

David A. Johnson, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, Virginia.

References

- 1.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–1511. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johanson J, Hwang C, Roach A. Prevalence of erosive esophagitis (EE) in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) Gastroenterology. 2001;120:233. [Abstract 1219] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fennerty MB, Johanson JF, Hwang C, Sostek M. Efficacy of esomeprazole 40 mg vs. lansoprazole 30 mg for healing moderate to severe erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med. 1998;104:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dent J, Brun J, Fendrick AM, et al. Genval Workshop Group. An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management – the Genval Workshop report. Gut. 1999;44(suppl 2):S1–S16. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.2008.s1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castell DO, Kahrilas PJ, Richter JE, et al. Esomeprazole (40 mg) compared with lansoprazole (30 mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:575–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahrilas PJ, Falk GW, Johnson DA, et al. Esomeprazole Study Investigators. Esomeprazole improves healing and symptom resolution as compared with omeprazole in reflux oesophagitis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1249–1258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nexium [package insert] Wilmington, Del: AstraZeneca LP; November 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, et al. Esomeprazole Study Investigators Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:656–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.3600_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dent J, Jones R, Kahrilas P, Talley NJ. Management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. BMJ. 2001;322:344–347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7282.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]