Abstract

Signals from different cellular networks are integrated at the mitochondria in the regulation of apoptosis. This integration is controlled by the Bcl-2 proteins, many of which change localization fromthe cytosol to the mitochondrial outer membrane in this regulation. For Bcl-xL, this change in localization reflects the ability to undergo a conformational change from a solution to integral membrane conformation. To characterize this conformational change, structural and thermodynamic measurements were performed in the absence and presence of lipid vesicles with Bcl-xL. A pH-dependent model is proposed for the solution to membrane conformational change that consists of three stable conformations: a solution conformation, a conformation similar to the solution conformation but anchored to the membrane by its C-terminal transmembrane domain, and a membrane conformation that is fully associated with the membrane. This model predicts that the solution to membrane conformational change is independent of the C-terminal trans-membrane domain, which is experimentally demonstrated. The conformational change is associated with changes in secondary and, especially, tertiary structure of the protein, as measured by far and near-UV circular dichroism spectroscopy, respectively. Membrane insertion was distinguished from peripheral association with the membrane by quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence by acrylamide and brominated lipids. For the cytosolic domain, the free energy of insertion ( ) into lipid vesicles was determined to be −6.5 k cal mol−1 at pH4.9 by vesicle binding experiments. To test whether electrostatic interactions were significant to this process, the salt dependence of this conformational change was measured and analyzed in terms of Gouy–Chapman theory to estimate an electrostatic contribution of ~−2.5 kcal mol−1 and a non-electrostatic contribution of ~−4.0 kcal mol−1 to the free energy of insertion, . Calcium, which blocks ion channel activity of Bcl-xL, did not affect the solution to membrane conformational change more than predicted by these electrostatic considerations. The lipid cardiolipin, that is enriched at mitochondrial contact sites and reported to be important for the localization of Bcl-2 proteins, did not affect the solution to membrane conformational change of the cytosolic domain, suggesting that this lipid is not involved in the localization of Bcl-xL in vivo. Collectively, these data suggest the solution to membrane conformational change is controlled by an electrostatic mechanism. Given the distinct biological activities of these conformations, the possibility that this conformational change might be a regulatory checkpoint for apoptosis is discussed.

Keywords: apoptosis, Bcl-2 family, conformational change, membrane insertion, protein-membrane interactions

Abbreviations used: DOPG, dioleoyl phosphatidyl glycerol; DOPE, dioleoyl phosphatidyl ethanolamine; DOPC, dioleoyl phosphatidyl choline; TBPC, 1,2-distearoyl-9,10-dibromo-SN-glycero-3-phosphocholine; Gdn, guanidine

Introduction

The Bcl-2 family of proteins are important in the regulation of apoptosis.1–6 To accomplish this regulation, many Bcl-2 proteins exhibit a dual structural nature. In the cytosol they act as soluble α-helical bundle proteins that integrate various cellular signals, and in the membrane they act as integral membrane proteins that regulate the release of cytochrome c and other apoptotic factors from the mitochondrion in a manner that is not fully understood.1,5,7–12 This dual structural nature does not arise from different classes of proteins, in solution and in the membrane; rather a single protein is able to adopt both solution and integral membrane conformations;9,10,13 an extreme example of a conformational change in signal transduction.

In the case of apoptosis, the importance of both solution and membrane conformations is well documented and demonstrated by the changes in localization of some Bcl-2 proteins during apoptosis.9,10,13 For example, Bax is localized in the cytosol adopting a solution conformation until a signal, still unknown, causes translocation to the mitochondrial outer membrane where it adopts an integral membrane conformation causing the release of mitochondrial proteins that activate caspases.13 For Bcl-xL, the localization before apoptosis is partly cytosolic and partly membrane associated.13 However, upon induction of apoptosis, Bcl-xL localizes to the mitochondrial outer membrane (and other organellar membranes) where it adopts an integral membrane conformation capable of ion conduction, which is thought to maintain the integrity of the mitochondrial outer membrane.14–16 How ion channel activity regulates apoptosis is contentious, but ion conduction is blocked by calcium and Bcl-xL also affects the gating of VDAC.16–18 Regardless of the exact mechanism, mutants of Bcl-xL with altered ion conduction properties also have altered apoptotic properties, confirming an important role for the membrane conformation of this protein in regulating apoptosis.19

Given that distinct biological activities have been ascribed to both the solution and membrane conformations of Bcl-xL,6,10,20,21 the solution to membrane conformational change might be an important regulatory checkpoint for apoptosis. For this reason we have begun to determine the salient features of this conformational change. To date, no protein receptor has been identified for this conformational change but the lipid cardiolipin is thought to be involved in targeting Bid, another Bcl-2 family member, to the mitochondrial outer membrane. Whether cardiolipin or other lipids are necessary for membrane localization of Bcl-xL is unknown.22 In fact for Bcl-xL, the solution to membrane conformational change has been reproduced in vitro with recombinant protein and synthetic lipids, suggesting that this process is not strictly lipid-dependent or receptor-mediated.20 Remarkably, this conformational change does not require the C-terminal, hydrophobic 24 residues of Bcl-xL that act as a transmembrane anchor.20,23 Indeed, the cystosolic domain that lacks these 24 residues, Bcl-xLΔTM, has similar ion channel properties to the full-length protein and retains apoptotic activity.20,21

Two requirements for the solution to membrane conformational change of the Bcl-xLΔTM in vitro have been identified: acidic pH and acidic lipids.20,23 These requirements are similar to the solution to membrane conformational changes of many bacterial toxins such as colicin A and the translocation domain of Diphtheria toxin.24–28 In fact, the solution conformations of these toxins are similar to Bcl-2 proteins, suggesting that they might have similar membrane conformations, or associate with the membrane by a similar mechanism.21 However, we previously reported differences in the thermodynamics that drive this conformational change.29 For many bacterial toxins this conformational change is aided by an acid-induced destabilization of the solution conformation in the absence of lipid vesicles.27,30–32 In these cases, the destabilization is thought to induce a molten globule formation that aids the conformational change. By contrast in the case of Bcl-xLΔTM, we found that the solution conformation was quite thermodynamically stable with a free energy of unfolding of ΔG°=14.6(±1.0) kcal mol−1 at pH 4.9;29 a pH at which it fully associates with anionic lipid vesicles.29 This thermodynamic stability seems unusually high for a protein whose activity requires a large conformational change and raises the question of the thermodynamic origins of this conformational change, which we address here. We demonstrate that the conformational change involves at least three distinct conformations for full-length Bcl-xL, two of which are membrane-associated. The structural nature of the more fully membrane-associated conformation is assessed spectroscopically and thermodynamically using Bcl-xLΔTM and lipid vesicles. We also determine the relative contribution from electrostatic or non-electrostatic interactions to the free energy of this process. The role of two molecules important in regulating activity of Bcl-2 proteins, calcium and cardiolipin, are also examined.

Results

Bcl-xL adopts at least three conformations in the presence of lipid vesicles

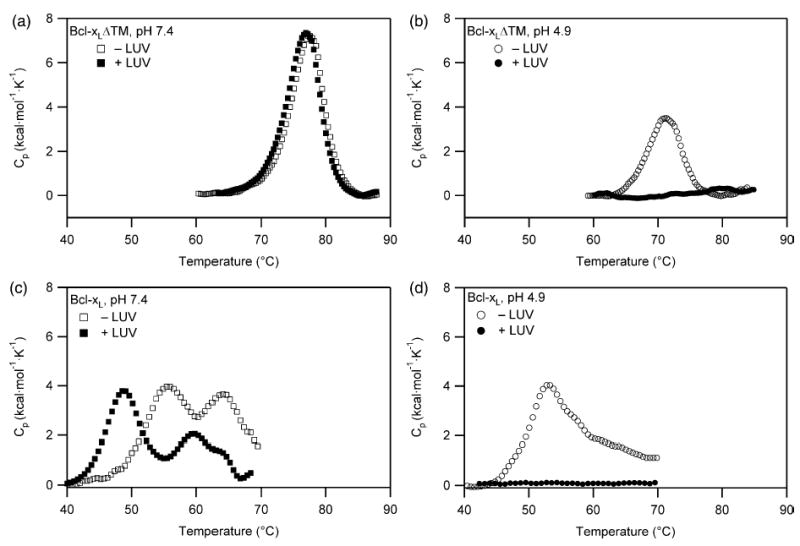

To study the solution to membrane conformational change of Bcl-xL, we monitored the thermal unfolding of two constructs of this protein in the absence and presence of lipid vesicles by differential scanning calorimetry, which is sensitive to enthalpic changes associated with conformational changes. Initially we characterized the pH-dependence to thermal unfolding of a construct lacking the C-terminal transmembrane domain, Bcl-xLΔTM, in the absence and presence of lipid vesicles (DOPC/DOPG, 60:40). At pH 7.4, the thermal unfolding profile of the protein does not significantly change upon addition of lipid vesicles (Figure 1(a)). By contrast at pH 4.9, the thermal unfolding profile of the protein disappears upon addition of lipid vesicles (Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

The Bcl-xL solution to membrane conformational change is pH-dependent involving at least three distinct conformations. (a) For Bcl-xLΔTM at pH 7.4, no association between protein and lipid vesicles is demonstrated by the absence of a change in the thermal unfolding transition of the protein upon addition of lipid vesicles in a 1:200 ratio. (b) By contrast, at pH 4.9 the thermal unfolding transition of Bcl-xLΔTM disappears suggesting a strong association with lipid vesicles upon addition. (c) For Bcl-xL at pH 7.4 in the absence of lipid vesicles, the C-terminal transmembrane domain of Bcl-xL unfolds first followed by the global unfolding of the protein. In the presence of lipid vesicles, an additional thermal transition is observed that is attributed to the unfolding of the cytosolic domain that is anchored to the lipid vesicle by its C-terminal transmembrane domain (d) For Bcl-xL at pH 4.9 in the presence of lipid vesicles, the thermal unfolding transition of the protein disappears, suggesting a strong association with lipid vesicles upon addition similar to Bcl-xLΔTM.

The disappearance of a thermal transition in the presence of lipid vesicles at pH 4.9 arises from one of two possibilities: (i) the protein is completely unfolded in the presence of the lipid vesicles at pH 4.9 even at low temperatures such that no unfolding transition occurs upon increasing the temperature; or (ii) the protein is associated with the lipid vesicles such that no unfolding transition occurs in the temperature range of the calorimetry experiment. The first possibility is ruled out because Bcl-xLΔTM is folded at pH 4.9 in the presence of vesicles as indicated by the far-UV CD spectrum at 25 °C (Figure 2(a)). Thus, these data indicate a strong interaction between Bcl-xLΔTM and lipid vesicles at pH 4.9, but not at pH 7.4, and confirm that the solution to membrane conformational change is independent of the C-terminal transmembrane domain.

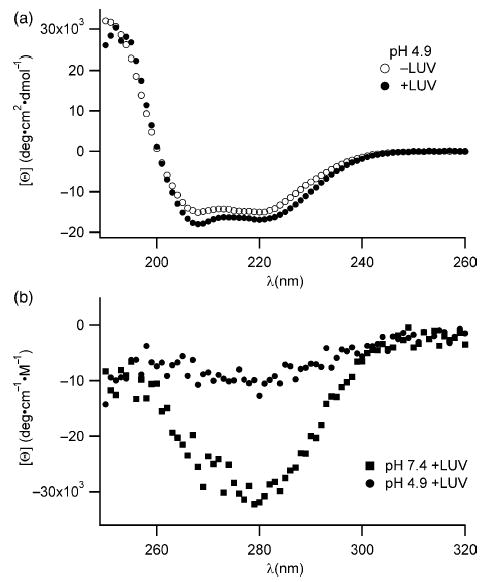

Figure 2.

Changes in the secondary and tertiary structure of Bcl-xLΔTM upon association with lipid vesicles suggest a gross conformational change. (a) The far-UV CD signal of the protein is significantly decreased only in the presence of lipid vesicles at pH 4.9 and not at pH 7.4, suggesting an increase in α-helical structure upon association with lipid vesicles. (b) The near-UV CD signal arising from the aromatic residues disappears only in the presence of lipid vesicles at pH 4.9 and not at pH 7.4, suggesting a loss in side-chain packing around aromatic residues in the hydrophobic core of the protein upon association with lipid vesicles.

These results suggest that the membrane conformation for full-length Bcl-xL at pH 7.4 would be anchored to the membrane by its C-terminal transmembrane domain with its cytosolic domain solvent-exposed. To test this hypothesis, we performed similar experiments with Bcl-xL. In contrast to Bcl-xLΔTM at pH 7.4 in the absence of lipid vesicles, Bcl-xL shows two thermal transitions with midpoints of 56 °C and 64 °C indicating that the C-terminal transmembrane domain induces a second thermal transition (Figure 1(c)). We attribute the lower thermal transition to a conformational change that exposes the C-terminal transmembrane domain and the higher thermal transition to global unfolding of the protein in solution. Another possibility is that the lower thermal transition arises from unfolding of a Bcl-xL dimer to monomer, as Bcl-xL is capable of being dimeric under certain conditions.33,34 However, we do not favor this possibility, because in our hands this protein is completely monomeric by size-exclusion chromatography (data not shown). Notably, the thermal transition for global unfolding of Bcl-xL is significantly lower (Tm=64 °C) than Bcl-xLΔTM (Tm=77 °C), suggesting that the presence of the C-terminal transmembrane domain destabilizes the fold of the full-length protein. While the Tm is often equated with the thermodynamic stability, ΔG°, they are formally not equivalent. Large changes in Tm for mutant proteins can arise if the temperature dependence on ΔG° is shallow. Also, the thermal unfolding is not reversible preventing quantitative interpretations. Therefore, we conclude from these data that Bcl-xL unfolds by a three-state mechanism in solution (tail in–tail out–unfolded).

In the presence of lipid vesicles at pH 7.4, Bcl-xL shows at least three thermal transitions with midpoints of 49 °C, 60 °C, and 64 °C (Figure 1(c)). Because Bcl-xL is partly in solution and partly membrane-bound under these conditions,20,23 we expected to observe two thermal transitions for the solution conformation. Accordingly, we attribute the highest thermal transition (Tm=64 °C) to the global unfolding of the protein in solution because this Tm coincides with this transition in the absence of lipid vesicles (Figure 1(c)). We attribute the lowest thermal transition of Bcl-xL in the presence of lipid vesicles to a membrane-bound conformation that has some folded portion of the molecule solvent-exposed, and therefore capable of thermally unfolding. Most likely this conformation is anchored by its C-terminal transmembrane domain to the membrane with its cytosolic domain solvent-exposed and able to thermally unfold. While other interpretations are possible, we favor this interpretation based on other data that imply membrane-bound Bcl-xL retains an intact BH3 binding pocket that is able to prevent tBid from activating Bax. One problem with our interpretation is the Tm observed for this transition is lower than expected based on the unfolding of Bcl-xLΔTM. However, a lower Tm would be expected when considering the electrostatics of Bcl-xL-membrane interaction. The cytosolic domain of Bcl-xL is acidic (calculated pI of 4.4) whose folding would be destabilized by the close proximity of a negatively charged membrane surface and be reported by a lower Tm. The middle thermal transition (Tm=60 °C) we attribute to the conformational change that exposes the C-terminal, transmembrane domain of the solution conformation. This thermal transition is slightly higher by 4 deg. C than that in the absence of lipid vesicles, suggesting that the presence of lipid vesicles slightly alters the thermal transition for this conformational change.

To examine the pH dependence of the solution to membrane conformational change, we performed similar experiments with Bcl-xL. At pH 4.9 in the absence of lipid vesicles, Bcl-xL shows a broad transition that appears to have degeneracy in the unfolding transitions. In the presence of lipid vesicles, the thermal unfolding profile of Bcl-xL disappears completely (Figure 1(d)), indicating a strong association with the lipid vesicles similar to Bcl-xLΔTM.

Taken together these results clearly indicate a pH-dependent solution to membrane conformation change for Bcl-xL that is independent of the C-terminal transmembrane domain. For this reason and that biological activity of the cytosolic domain is similar to the full-length molecule,20,21 we focused on characterizing this process further with Bcl-xLΔTM.

Association of Bcl-xLΔTM with lipid vesicles is coupled with 2° and 3° structural changes

Dramatic enthalpic changes such as those observed in our calorimetry experiments are usually coupled with large conformational changes, which were further investigated using spectroscopic methods. We therefore measured the change in secondary structure using CD spectropolarimetry upon association with lipid vesicles. At pH 7.4, where there is little association between Bcl-xLΔTM and lipid vesicles, we observe no significant changes as expected between the far-UV CD spectra of the protein in the absence and presence of lipid vesicles (data not shown). By contrast at pH 4.9, the far-UV CD spectrum of Bcl-xLΔTM changes in the presence of lipid vesicles indicating changes in secondary structure (Figure 2(a)). The mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm at pH 4.9 upon the addition of lipid vesicles decreases by 2000 deg cm−2 dmol−1 residue−1, which translates to an increase in α-helix content by ~13% compared to the solution conformation (in the absence of lipid vesicles).

To determine changes in tertiary structure upon interaction with lipid vesicles, we collected the near-UV CD spectra and found no significant differences between the spectra in the presence or absence of lipid vesicles at pH 7.4, as expected. By contrast at pH 4.9 in the presence of lipid vesicles, the near-UV CD signal increased significantly, suggesting a dramatic tertiary structural change (Figure 2(b)). Such changes in ellipticity derive from an averaging of the rotameric states of the side-chains of aromatic amino acids (primarily tryptophan) upon association with lipid vesicles. These spectral changes could arise from the tryptophan residues becoming solvent-exposed or inserted in the fluid-like membrane, and is consistent with a change in tertiary structure of Bcl-xLΔTM upon membrane association.

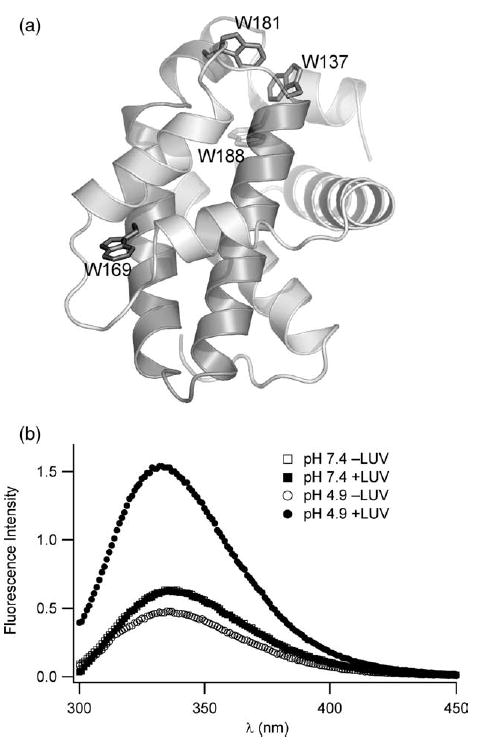

To confirm the observations from near-UV CD spectropolarimetry and probe the local environment of the tryptophan residues, we measured changes in the fluorescence emission spectrum of the protein upon addition of lipid vesicles at pH 7.4 and pH 4.9. At pH 7.4, the addition of lipid vesicles does not cause significant changes in the fluorescence emission spectrum of the six Trp residues in Bcl-xLΔTM (Figure 3(a)). However, at pH 4.9 upon the addition of lipid vesicles, the fluorescence intensity at λmax increases and shifts to the blue by 4 nm (Figure 3(b)). The structure of Bcl-xLΔTM indicates the presence of tryptophan residues in both polar and non-polar environments in the protein. The blue shift in the λmax suggests a net shift of the tryptophan residues towards a more non-polar environment upon the addition of lipid vesicles. This observation is consistent with the insertion of tryptophan residues into the non-polar hydrophobic core of the membrane bilayer. The increase in fluorescence intensity is consistent with this interpretation; however, intensity changes in fluorescence are more difficult to interpret as they can arise from changes in either radiative or non-radiative decay processes.35 The observations from CD and fluorescence taken together indicate a dramatic conformational change in Bcl-xLΔTM going from solution to the membrane at pH 4.9. This membrane conformation appears to have stable 2° structure but a more unfolded 3° structure than the solution conformation.

Figure 3.

A pH and lipid vesicle dependent conformation change of Bcl-xLΔTM is confirmed by tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra. (a) The solution conformation of the cytosolic domain of Bcl-xL reveals a hydrophobic α-helical hairpin (shaded) surrounded by a sheath of amphiphilic α-helices (1MAZ.pdb). Six tryptophan residues served as spectroscopic probes of membrane insertion; four are highlighted. A large unstructured loop (residues 26–83) containing two tryptophan residues is omitted for clarity but this loop is present in our constructs. (b) At pH 7.4, tryptophan fluorescence emission does not change upon addition of lipid vesicles consistent with no association between protein and lipid vesicles. However, at pH 4.9, tryptophan fluorescence emission dramatic increases with a blue shift in λmax upon association with lipid vesicles, suggesting a net shift in the tryptophan residues to a more non-polar environment upon association with lipid vesicles at pH 4.9.

Reduced solvent accessibility of tryptophan residues suggests membrane insertion

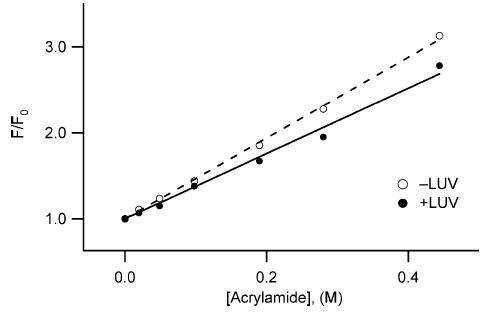

To confirm that the solution to membrane conformational change resulted in sequestration of tryptophan residues away from solvent, we measured the solvent accessibility of the tryptophan residues in both the solution and membrane conformations at pH 4.9 using acrylamide, a membrane-impermeable fluorescence quencher.36,37 In the absence of lipid vesicles, the Stern–Volmer quenching constant, KSV was 4.73 M−1 and decreased to 3.90 M−1 in the presence of lipid vesicles (Figure 4). A decrease in KSV value can arise from either a decrease in the fluorescence lifetime, τ0, or a decrease in the bimolecular rate constant for collisions between the fluorophore and quencher, kQ, because KSV is formally equal to the product of these two, or KSV=kQ×τ0.38 Therefore, we measured tryptophan fluorescence lifetime by time-resolved methods.39–41 The results indicate that the mean fluorescence lifetime, 〈τ0〉, increased almost twofold in the presence of lipid vesicles (data not shown). Therefore, the average bimolecular quenching rate constant for acrylamide quenching, kQ (=KSV/〈τ0〉) is decreased more than twofold in the presence of lipid vesicles. These observations are consistent with a structural transformation that protects tryptophan residues from solvent exposure upon association with lipid vesicles.

Figure 4.

Solvent accessibility of tryptophan residues is reduced in the membrane conformation of Bcl-xLΔTM. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence quenching of Bcl-xLΔTM, in solution and in the presence of lipid vesicles at pH 5.0, was measured as a function of increasing concentrations of acrylamide, a membrane impermeable quencher. The data fit well to the Stern–Volmer relation with a Stern–Volmer quenching constant, KSV, estimated from the slope to be 4.73 M−1 for Bcl-xLΔTM in solution (○), and 3.90 M−1 in the presence of lipid vesicles (•). The correlation coefficients were 0.99 for the linear fits. The data suggest a net increase in protection of tryptophan residues from solvent exposure upon interaction with lipid vesicles.

Tryptophan residues insert deeply into the bilayer of the lipid vesicles

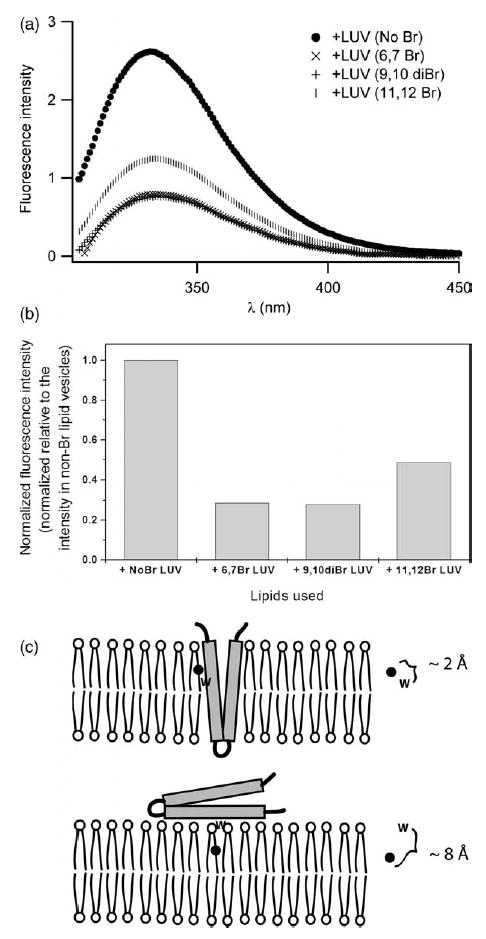

To differentiate protein binding to the surface from insertion into lipid vesicles, we estimated the depth of insertion of Bcl-xLΔTM into the lipid bilayer by a fluorescence quenching technique using phospholipids brominated at different positions along the acyl chain. Collisonal quenching between the Trp fluorophore and brominated phospholipids leads to a decrease in the fluorescence signal that is distance-dependent and readily observed using steady-state fluorescence.36,42,43 At pH 5.0 in the presence of non-brominated lipid vesicles, the fluorescence intensity is dramatically increased to more than three times that observed in the absence of lipid vesicles (Figure 5(a)). By contrast, in the presence of vesicles composed of lipids brominated more than halfway down the acyl chain at the 11,12 position, the fluorescence intensity is quenched over 50% relative to that in lipid vesicles comprised of non-brominated lipids (Figure 5(b)). Strikingly, the fluorescence intensity decreased over 70% in the presence of lipid vesicles comprised of lipids brominated at the 6,7 position of the acyl chain. The fluorescence intensity also decreased over 70% in the presence of lipid vesicles comprised of lipids brominated at the 9,10 position of the acyl chain.

Figure 5.

The membrane conformation of Bcl-xLΔTM is deeply inserted into the membrane bilayer. (a) Fluorescence emission spectra were collected in the presence of lipid vesicles brominated at different positions along the fatty acyl chain. Emission spectra were collected at pH 5.0 in the presence of 150 mM NaCl with excitation at 295 nm. (b) Data from fluorescence quenching experiments normalized to the λmax of the fluorescence emission from protein in non-brominated lipid vesicles. (c) The quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence by phospholipids brominated at different points along the fatty acyl chain is distance dependent. Such data can distinguish between the insertion of the hydrophobic helical hairpin into the bilayer and the peripheral association of the hairpin with the membrane surface using the parallax method.44,45 Our data are consistent with insertion.

Because quenching is distance dependent,36,42 fluorescence quenching data obtained from lipid vesicles comprised of lipids brominated at different depths can be used to estimate the depth of membrane penetration using parallax methods.44,45 From these estimates, our data suggest that the membrane conformation of Bcl-xLΔTM differs substantially from the solution conformation with tryptophan residues buried deeply into the membrane bilayer reaching at least to the middle of the acyl chains of the outer leaflet of the phospholipid vesicles (Figure 5(c)). Given the known location of the tryptophan residues in the solution conformation of Bcl-xLΔTM (Figure 3(a)), we interpret these data to be consistent with membrane insertion of at least the hydrophobic helical hairpin that is comprised of helices 5 and 6. However our data cannot discriminate between this umbrella-like model and one in which the protein is more fully inserted.

To gain preliminary kinetic information about the membrane insertion process, we monitored the decrease in fluorescence intensity as a function of time using lipid vesicles brominated at the 6,7 position. The data were well fit to a single-exponential with a time constant of ~170 ms, suggesting the insertion process is a first-order rate process that is relatively fast (data not shown).

Electrostatic contributions to the solution to membrane conformational change

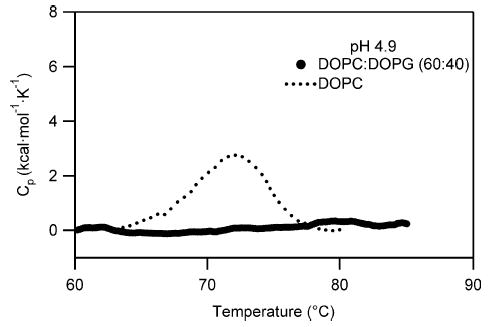

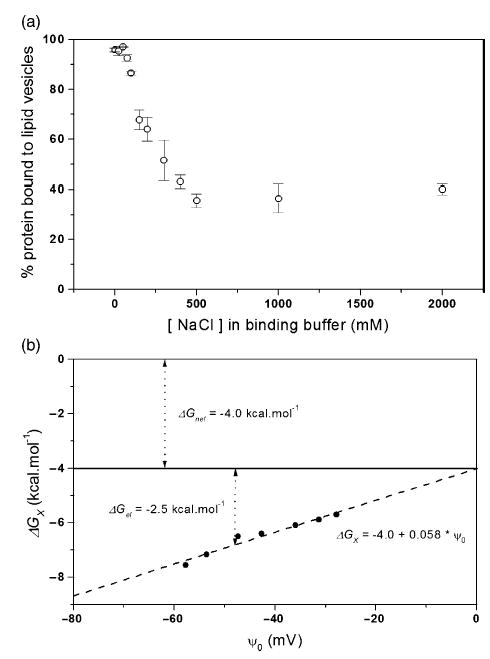

To confirm the requirement for anionic lipids for the solution to membrane conformational change of Bcl-xLΔTM, we indirectly detected binding to lipid vesicles at pH 4.9 with no net charge (100% DOPC) using differential scanning calorimetry (Figure 6). A thermal unfolding transition for Bcl-xLΔTM was observed indicating that the presence of anionic lipids is necessary for the association of Bcl-xLΔTM with lipid vesicles. To confirm these results and distinguish the relative contributions from electrostatic and non-electrostatic interactions to the free energy of insertion to lipid vesicles, we measured protein binding to negatively charged lipid vesicles (60:40, DOPC/DOPG) as a function of salt concentration using a sedimentation assay. Protein binding to lipid vesicles decreased by over 60% upon increasing salt concentrations up to 500 mM NaCl (Figure 7(a)). At this point, further addition of NaCl had no effect on association between protein and lipid vesicles indicating that a large non-electrostatic component to membrane insertion is present as expected.

Figure 6.

Anionic lipid dependence suggests an electrostatic component to the solution to membrane conformational change of Bcl-xLΔTM. A strong association of protein with lipid vesicles is only observed in the presence of lipid vesicles comprised of anionic lipids, because the thermal unfolding transition of the protein disappears only in the presence of lipid vesicles containing the negatively charged DOPG and not in the presence of lipid vesicles containing 100% of the net neutrally charged DOPC vesicles.

Figure 7.

Electrostatic contribution of membrane insertion is confirmed by the salt dependence of Bcl-xLΔTM association with lipid vesicles at pH 5.0. (a) Protein binding to lipid vesicles as a function of increasing concentration of NaCl was measured by a sedimentation assay. (b) The free energy of membrane insertion, , arises from electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions as discussed in the text. The y-intercept estimates the non-electrostatic contribution, , of ~ −4.0 kcal mol−1 and is independent of pH. The slope indicates the effective charge on the protein that is modulated by electrostatic interactions, zeff, of ~2.3. Under conditions with buffer and 150mM NaCl, I=0.2, the free energy contribution from electrostatics, is about −2.5 kcal mol−1.

To describe this effect more quantitatively, we used these data to determine a free energy of insertion, , as a function of estimated membrane surface potential, ψo (equation (3)). A plot of versus ψo yields the non-electrostatic contribution to the free energy of insertion, (the y-intercept) and the effective charge of the protein, zeff (the slope) (Figure 7(b)). The electrostatic contribution can then be readily estimated at any membrane surface potential desired using equation (3). Our lipid vesicle binding data are well fit by this relation (r2=0.98) with a of –4.0 kcal mol−1 and an effective charge of on Bcl-xLΔTM of −2.3. We estimate the electrostatic contribution to the free energy of insertion at pH 4.9 to be =−2.5 kcal mol−1 at an ionic strength close to physiological conditions (I=0.2 M).

This electrostatic contribution to the solution to membrane conformational change could arise from both changes on the surface of the protein and of the lipid vesicles. However, we expect it to primarily derive from acid-induced changes occurring on the surface of the protein because the pKa value of the lipid headgroups is 2.6 and therefore would not be contributing significantly to this process.46

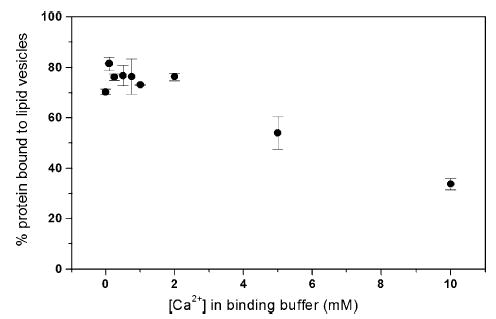

Calcium does not specifically influence the conformational change

The surface of Bcl-xLΔTM is highly negatively charged with a calculated pI of 4.4. Divalent cations like Ca2+ can mediate interactions between negatively charged protein and membrane surfaces.47–49 Furthermore, Ca2+ regulates Bcl-2 activity in vivo and blocks ion channel activity of Bcl-xL in vitro.11,17 Therefore, to test whether calcium might affect membrane insertion, we measured the association of Bcl-xLΔTM with lipid vesicles at pH 5.0 as a function of Ca2+ concentration. Addition of Ca2+ in the form of CaCl2 caused no significant changes in the association between protein and lipid vesicles (Figure 8). The pH-dependent binding of Bcl-xLΔTM to lipid vesicles remained unaffected at Ca2+concentrations up to 200 μM (20-fold over Bcl-xLΔTM concentration). Addition of Ca2+ at concentrations greater than 200 μM decreased binding, but this could be attributed to a non-specific salt screening effect on the binding of Bcl-xLΔTM to lipid vesicles. Binding measurements performed at pH 6 and 8 with 10 mM Ca2+ showed no calcium-dependent effect (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Calcium does not specifically influence the interaction of Bcl-xLΔTM with lipid vesicles. Protein binding to lipid vesicles at calcium concentrations ranging from 0 mM to 10 mM was not affected more than anticipated from electrostatic considerations, suggesting no specific role for calcium in the membrane insertion process.

These data can be used to evaluate the validity of the Gouy–Chapman approach used above for estimating the relative contributions to the free energy of insertion. Gouy–Chapman theory predicts that the interaction will follow a squared-dependence on the cation charge. The analysis of our Ca2+ data using this formalism confirms the approach as similar estimates of the relative electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions are determined (Supplementary Data).

Discussion

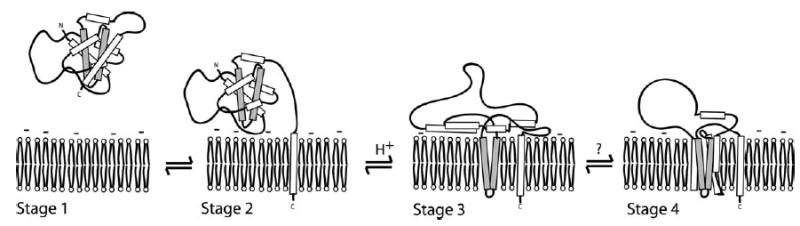

The solution to membrane conformational change of Bcl-xL is important in the regulation of apoptosis and here we report a structural and thermodynamic characterization of this process. Our results and the data from other studies support a four-stage model for the solution to membrane conformational change of Bcl-xL (Figure 9). In this model, the solution conformation exists by sequestering its C-terminal transmembrane domain away from aqueous solvent bound by its own BH3 binding pocket in a manner similar to that observed for Bax50 (stage 1), or perhaps into a second Bcl-xL molecule to form a dimer,33 although we observe no evidence for dimer formation of recombinant Bcl-xL. The next stage of the model is the exposure of the C-terminal transmembrane domain to insert into the membrane but the overall fold of the cytosolic domain is retained (stage 2). In this stage, the protein is anchored to the membrane surface with its cytosolic domain poised to bind cytosolic factors via its now-exposed BH3 binding pocket. Substantial support for the ability of BH3-only proteins and other ligands to bind this conformation exists.51–54 Binding of such ligands would be expected to stabilize the solution conformation preventing Bcl-xL from adopting its fully membrane associated conformation. In the third stage of the model, the entire protein becomes fully associated with the membrane by insertion of at least the hydrophobic helical hairpin (stage 3). This conformation is supported by other biochemical and structural data,55,56 and is consistent with what is proposed for the bacterial toxins.24,25,31,32,57 In the final stage of the model, we postulate that the protein forms a pore by either oligomerization via the hydrophobic helical hairpin, or by insertion across the membrane of the amphiphilic α-helices to form the lumen of a monomeric or multimeric pore (stage 4). Our data cannot distinguish between stages 3 and 4. Other evidence is also inconclusive, reflecting the difficulty of the problem. The membrane conformation of Bcl-xLΔTM was first reported in detergent micelles by size-exclusion chromatography to be dimeric,58 whereas a later study by analytical ultracentrifugation revealed it to be monomeric;55 perhaps these results underscore that this protein might adopt more than one oligomeric state in the membrane. Indeed, O’Neill et al. recently reported cross-linking experiments that suggests a mixed population of primarily monomeric and dimeric conformations in lipid vesicles.34

Figure 9.

A hypothetical model for the solution to membrane conformational change of Bcl-xL. Bcl-xL is localized to the cytosol and organellar membranes and translocates to the mitochondria during apoptosis. Protein localized in the cytosol presumably has the C-terminal transmembrane domain sequestered into the BH3 binding pocket of the protein in a conformation similar to Bax50 (stage 1). Protein localized to the membrane is anchored by the C-terminal transmembrane domain with the cytosolic domain of Bcl-xL poised to receive signals (stage 2). Insertion of the cytosolic domain via the hydrophobic helical hairpin into the membrane bilayer interior is caused by acidification or some other signal (stage 3). In the last step, a fully inserted membrane conformation is assembled by either oligomer formation via the helical hydrophobic hairpin (not shown), or by full insertion of the amphiphilic α-helices to span the membrane bilayer with their hydrophilic faces lining the lumen of the ion channel (stage 4). The results presented here support the first two stages of the model and that the transition to stage 3 is controlled by an electrostatic mechanism. Our data cannot distinguish between stages 3 and 4.

While this model is not original, our data provide the first unambiguous evidence for the first two stages of this model. Furthermore, we show that the transition between stages 2 and 3 is controlled by an electrostatic mechanism that is of the order of most allosteric regulatory mechanisms.59 In this sense, the thermodynamics of the solution to membrane conformational change of Bcl-xL appears to be exquisitely tuned to the different structural conformations important in apoptotic regulation. At physiological pH, where no membrane insertion occurs, the non-electrostatic contribution to the free energy of membrane insertion still exists. This value is relatively small (~4.0 kcal mol−1) when compared to the free energy of unfolding of the solution conformation (~15 kcal mol−1) and suggests that the membrane conformation is not significantly populated, which is consistent with our measurements.29 However, the value of ~4 kcal mol−1 does not fully represent the energetics of this process because it excludes significant contributions from the loss of translational and rotational degrees of freedom upon membrane insertion. Upon membrane insertion at least one translational degree of freedom and two rotational degrees of freedom are lost, and because of the corresponding decrease in entropy the free energy of this process increases by approximately 15 kcal mol−1 that is not reflected in our measurements.60 Therefore, the total non-electrostatic component to the free energy of insertion (ΔGnel) can be estimated at ~19 kcal mol−1.

These considerations imply that the membrane conformation is thermodynamically favored over the solution conformation, and therefore must be kinetically trapped at physiological pH until a signal is received that lowers the activation energy for membrane insertion.61,62 Thus, Bcl-xL appears similar to the pH-dependent solution to membrane conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin, which is also kinetically trapped. In the case of hemagglutinin, the binding of protons lowers the activation energy for the conformational change.62 Whether the signal in vivo for Bcl-xL is the same, or not, remains to be determined, but a lowering of the cytosolic pH upon induction of apoptosis has been reported.63 Perhaps an increase in temperature might contribute to the conformational change as was recently reported for the activation of the Bcl-2 proteins Bax and Bak.64 Nevertheless, the results presented here suggest that an electrostatic mechanism of a few kcal mol−1 is all that is necessary to lower the activation energy for this profound conformation change. An energy barrier of this size is typical of many regulatory mechanisms, where a sufficient barrier to active conformations is necessary to prevent uncontrolled activation.61

Such electrostatic interactions have been shown to play important roles in other systems that cycle on and off membranes, including the myristoyl-electrostatic switch of the myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate protein (MARCKS).65–67 The MARCKS protein is anchored to the membrane by a myristoyl tail but this interaction is not sufficient to sustain membrane localization of this protein. For full association with the membrane, favorable electrostatic interactions are required between its effector domain and the negatively charged, inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. This electrostatic association is reversible upon phosphorylation of the effector domain, which changes the net charge of the protein enough to allow its localization to the cytosol.68 Of course, this exact mechanism is not known to apply to Bcl-xL; however, the general principle is the same in which a small change in the surface charge affects membrane interactions. Whether Bcl-xL is governed by a discrete switch involving only a few residues such as the MARCKS protein, or arises from a change in the ensemble of conformational states that is triggered by altered pKa values of several residues remains to be determined.

In conclusion, the solution to membrane conformational change of Bcl-xL involves at least three structurally distinct and thermodynamically stable conformations, a solution conformation and two membrane conformations. It is likely that each conformation has distinct biological activity and that changes between these conformations might be checkpoints for regulating apoptosis. Therefore, a potentially significant outcome of this model is that it predicts pharmacological intervention of Bcl-xL could occur at each conformation, not just at the second conformation (stage 2) that is the target of the majority of BH3 peptidomimetics and other small molecules currently under development.52–54

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

A DNA sequence encoding human Bcl-xL or Bcl-xLΔTM (1–209) lacking the C-terminal 24 amino acid residues was sub-cloned into the pGB1 fusion construct using standard procedures.69 These constructs produce Bcl-xL proteins as a fusion protein with His6-tagged B1 domain from the streptococcal G protein on the N terminus (GB1 domain). The presence of the GB1 domain in the fusion construct increases protein expression and solubility in bacterial cells. A tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease recognition site between the GB1 domain and Bcl-xL enables isolation of Bcl-xL away from GB1 following cleavage with TEV protease. However, cleavage with TEV protease leaves Bcl-xL with the amino acid sequence GEF at the N terminus as a cloning artifact. Escherichia coli cells (Tuner DE3) containing this plasmid construct were grown at 37 °C in LB medium containing carbenicillin (50 μg/ml) to an A600 of ~0.7. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.3 mM IPTG and the cells were allowed to grow at 25 °C for 10–12 h. At this time, chloramphenicol was added to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml to increase the amount of protein expressed in the soluble fraction and cells were maintained at 25 °C for an additional 6–8 h after which the cells were harvested by centrifugation.70,71 The cell pellet was resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris, 0.5 M NaCl (pH 8.0)) containing protease inhibitors and 1 mg/ml lysozyme, incubated at 4 °C for 2 h and lysed by three passes using a French press. The fusion protein present in the soluble fraction was then isolated by affinity purification on a Ni2+ chelating column (Ni2+ chelating Sepharose; GE Healthcare), followed by dialysis into TEV protease cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT). The fusion protein was then cleaved for at least 4 h at 4 °C with a His-tagged recombinant TEV protease (1:100 (w/w)) to generate Bcl-xL or Bcl-xLΔTM. The reaction mixture was loaded onto the Ni2+ chelating column again and the flow-through fractions containing Bcl-xL or Bcl-xLΔTM were collected, concentrated, and loaded onto a Superdex 75 gel-filtration column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 1mM EDTA. For Bcl-xL, the protein eluted as one peak at the elution volume expected for monomeric protein. However, for Bcl-xLΔTM the protein eluted as two peaks correspond to monomer and dimer with the majority of protein (>85%) consistently being monomeric under these conditions. The monomeric fractions containing Bcl-xLΔTM were collected and quantified using UV-absorbance (Bcl-xLΔTM ɛ280= 41,820 M−1 cm−1 in 6 M guanidine (Gdn) HCl). The yield of pure protein was approximately 0.3 mg/l for Bcl-xL (Bcl-xL ɛ280=47440 M−1 cm−1 in 6 M GdnHCl), and 15–20 mg/l for Bcl-xLΔTM. The purity was greater than 95% as judged by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE. 15N-labeled samples were prepared in a similar manner in the presence of 15NH4Cl in M9 minimal medium.72 Protein was stored at 4 °C.

Preparation of large unilamellar vesicles (LUV)

1,2-Distearoyl-9,10-dibromo-SN-glycero-3-phosphocholine (TBPC), dioleoyl phosphatidyl glycerol (DOPG), lissamine rhodamine B-labeled dioleoyl phosphatidyl ethanolamine (Rh-DOPE), 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl-(6,7-dibromo)-SN-glycerophosphocholine and 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl-(11,12-dibromo)-SN-glycerophosphocholine, and cardiolipin were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. The lipids were mixed to give the desired ratio and the chloroform from the lipid mixture was evaporated. Water was added to the lipids to reach a final concentration of lipids around 20 mM. The lipid suspension in aqueous solution was subjected to freeze-thaw cycles three times and extruded through a 100 nm polycarbonate filter 11 times to make large unilamellar vesicles (LUV) with an average size around 100 nm.73 The homogeneity of these lipid vesicles was confirmed by size-exclusion chromatography. The lipid vesicles were stored at 4 °C.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Differential scanning calorimetry experiments were carried out on a N-DSC nano differential scanning calorimeter (Calorimetry Sciences Corp., Applied Thermodynamics) or VP-DSC(Microcal Inc.). All samples were scanned from 10 °C to 90 °C using a scan rate of 1 deg. C min−1. For Bcl-xL the protein concentration was 11 μM protein and for Bcl-xLΔTM the protein concentration was 40 μM. For the samples in the presence of lipid vesicles, lipid vesicles (DOPC/ DOPG, 60:40) were added to a final concentration such that the protein/lipid (P:L) ratio was kept at 1:200. Samples containing protein with and without lipid vesicles were prepared at pH 7.4 and pH 4.9 using 20 mM sodium phosphate and 20 mM sodium acetate buffers, respectively. All of the thermal unfolding transitions were found to be irreversible under conditions reported and several others tested. Therefore, no further thermodynamic analyses are justified and the data are interpreted only qualitatively.

Circular dichroism spectropolarimetry

For the far-UV experiments, 40 μM samples of Bcl-xLΔTM were prepared in 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.9) with and without lipid vesicles composed of DOPC/DOPG (60:40). For spectra containing lipid vesicles, the lipid concentration was 8 mM resulting in a protein/lipid (P/L) ratio of 1:200. Blank spectra were collected with buffer and with buffer containing lipid vesicles. Spectra were collected using a 0.1 mm path-length cell scanning from 260 nm to 190 nm at a scan rate of 20 nm min−1 with a response time of 2 s. Twenty spectra were collected and averaged for each sample. For the near-UV CD experiments, protein concentration was 7.5 μM and lipid concentration in the vesicles was 1.5 mM for a P/L ratio of 1:200. Spectra were collected with wavelengths ranging between 320 nm and 250 nm in a 1 cm path-length cell. Scan speed was 20 nm min−1, response time was 2 s and 30 accumulations were averaged for each sample. The temperature was maintained at 25 °C during all experiments.

Steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy

The association of protein and lipid vesicles was monitored by observing the emission spectrum from tryptophan fluorescence of Bcl-xLΔTM, which contains six tryptophan residues (Figure 3(a)), using a PTI model A1010 fluorimeter (Photon Technology International, Canada). The excitation wavelength was 295 nm and the emission spectrum was collected between 305 nm and 450 nm at a scan rate of 1 nm s−1. The slit widths for excitation and emission were kept at 1 nm and 5 nm, respectively, with the experiment conducted at 25 °C. For these measurements, lipid vesicles were prepared as described above using four different lipid compositions: (i) DOPC and DOPG in a 60:40 ratio; (ii) 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl (6,7-dibromo)-SN-glycerophosphocholine and DOPG in a 60:40 ratio; (iii) 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl (11,12-dibromo)-SN-glycerophosphocholine and DOPG in a 60:40 ratio; (iv) 1,2-distearoyl (9,10-dibromo)-SN-glycerophosphocholine and DOPG in a 60:40 ratio doped with Rh-DOPE. The concentrations of protein and lipid vesicles were 1 μM and 200 μM, respectively, to give a protein/lipid ratio of 1:200. The protein–lipid mixtures were incubated overnight at room temperature before data collection. Data were collected using 20 mM sodium acetate at pH 4.9, 20 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4 and potassium acetate buffer at pH 5.0 with an ionic strength I=0.05 M.74

Acrylamide quenching of tryptophan fluorescence

Solvent accessibility of Bcl-xLΔTM tryptophan residues in the solution and membrane conformations were determined by fluorescence quenching experiments using acrylamide.36 Emission spectra of a 3 μM sample of Bcl-xLΔTM in the absence and presence of lipid vesicles (at 600 μM to maintain a P/L of 1:200) were collected at 25°C from 305 nm to 400 nm upon excitation at 295 nm. For these measurements, acrylamide from a 4M stock solution was added to the protein–lipid vesicles mixture to give final acrylamide concentrations of 0, 0.02, 0.049, 0.098, 0.19, 0.28 and 0.444 M. Samples were incubated overnight at 25 °C before steady-state fluorescence emission spectra were collected. The spectra were corrected for blank, dilution, and inner filter effects. The data were analyzed using the Stern–Volmer equation for collisional quenching,36,75 F0/F=1+KSV[Q], where F0 and F are the initial steady-state emission intensities at λmax in the absence and presence of acrylamide, [Q] is the molar concentration of acrylamide, and KSV is the Stern–Volmer quenching constant.

Sedimentation assay to measure protein binding to lipid vesicles

The association of Bcl-xLΔTM with lipid vesicles was measured using a modification of an assay described by Wimley et al.76 This microfuge-based assay uses lipid vesicles comprised of brominated lipids that sediment at lower speeds (due to their higher density) when compared to non-brominated lipid vesicles that require ultracentrifugation-based sedimentation methods. This method avoids the non-idealities in the apparent Kx measurements that are introduced at higher sedimentation forces. Sedimentation was done in three steps with progressively increasing speeds, which was shown by Wimley et al. to be necessary to remove a centrifugation speed dependence of the partition coefficients.76 The assay was optimized to identify conditions where there was complete sedimentation of the lipids in order to remove errors in the determination of protein concentration in the supernatant due to contamination from the lipid fraction. TBPC and DOPG were mixed in a molar ratio of 60:40 and doped with 0.25% Rh-DOPE to enable visualization of the lipid fraction. Bcl-xLΔTM (10 μM) and lipid vesicles (2 mM) were incubated in the presence of an acetate buffer with an ionic strength I=0.05 M,74 or varying concentrations of added salt, NaCl. Water was added to bring the total volume of the reaction up to 100 μl. The mixture was incubated overnight at 25 °C. It was then subject to centrifugation at increasing speeds (4000, 9000, 18,000g) for 30 min each. At the end of the centrifugation, the supernatant was removed from the tube and assayed for total protein concentration by the Bradford method.77

A standard curve for the Bradford assay was generated from known concentrations of Bcl-xLΔTM, determined by the absorbance at 280 nm in the presence of 6M GdnHCl. The amount of Bcl-xLΔTM bound to the vesicles was estimated using the difference between the amount of protein used in the reaction and the amount of protein remaining in the supernatant. The percentage of protein bound to the vesicles was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

To determine the effects of the lipid cardiolipin (CL) on Bcl-xLΔTM binding to lipid vesicles, protein samples were incubated with lipid vesicles comprised a lipid composition of DOPC/DOPG/CL (70:20:10) that maintains the same membrane surface density as the vesicles made with DOPC/DOPG (60:40). To determine the effects of Ca2+ on Bcl-xLΔTM binding to lipid vesicles, protein samples were incubated with vesicles at pH 5.0 acetate buffer (I= 0.05 M)74 with 150 mM NaCl and various amounts of CaCl2 ranging between 0 mM and 10 mM. Following overnight incubation and centrifugation of the samples, the supernatant was isolated and then assayed for total protein using the Bradford assay and the percentage of protein bound to lipid vesicles was calculated as shown above in equation (1). The free energy of Bcl-xLΔTM to partition into lipid vesicles was calculated as follows:78,79

| (2) |

Where [P]total, [P]free, [L] and [W] are the concentrations of total protein in the reaction mixture, protein in solution, lipids and water, respectively.

The free energy of insertion is comprised of electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions:

| (3) |

where the zeff is the effective charge on the protein, F is Faraday’s constant, ψo is the membrane surface potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, and Knel is the protein–membrane partition coefficient in the absence of an electrical potential at the membrane surface (at ψo= 0).80 Thus, if the membrane surface potential, ψo, is known, then the relative contribution to the free energy of insertion can be obtained from the plot of versus ψo. From this analysis, the non-electrostatic contribution to the free energy of insertion, , is simply the y-intercept and the effective charge of the protein, zeff, is the slope.

A reasonable estimate for the membrane surface potential, ψo, can be obtained based on considerations from Gouy–Chapman theory and a physical model that estimates the adsorption of ions to a charged membrane surface.80–84 In this estimation, the membrane surface potential is determined from the surface area of lipids, the fraction of negatively charged head groups of the lipids, and the ionic strength of the bulk solution.85 That is, we can estimate the membrane surface potential from our lipid composition at any salt concentration (see Supplementary Data). Thus, given values for Bcl-xLΔTM-lipid vesicle binding as a function of ionic strength, the relative contribution to the free energy of insertion can be obtained from equation (3) and a plot of versus ψo. This approach has been experimentally verified in several systems.80,84,86

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dimtri Toptygin and Lenny Brand for help with time-resolved fluorescence experiments and to Bertrand Garcia-Moreno for helpful comments. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant RO1GM067180 (to R.B.H.), American Cancer Society award IRG-58-005-41 (to R.B.H.), start-up funds provided by JHU to R.B.H. J.W.C. was the recipient of HHMI and Pfizer summer undergraduate research fellowships. V.K. and A.S. were supported, in part, by National Science Foundation grant NSF 0131241 awarded to Ernesto Freire.

Footnotes

Edited by I. B. Holland

References

- 1.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD. Bcl-2-family proteins and the role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 protein family: arbiters of cell survival. Science. 1998;281:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1899–1911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vander Heiden MG, Thompson CB. Bcl-2 proteins: regulators of apoptosis or of mitochondrial homeostasis? Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:E209–E216. doi: 10.1038/70237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelekar A, Thompson CB. Bcl-2-family proteins: the role of the BH3 domain in apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:324–330. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucken-Ardjomande S, Martinou JC. Regulation of Bcl-2 proteins and of the permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane. C R Biol. 2005;328:616–631. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed JC. Double identity for proteins of the Bcl-2 family. Nature. 1997;387:773–776. doi: 10.1038/42867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schendel SL, Montal M, Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins as ion-channels. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:372–380. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oakes SA, Opferman JT, Pozzan T, Korsmeyer SJ, Scorrano L. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ dynamics by proapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1335–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00482-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vander Heiden MG, Chandel NS, Williamson EK, Schumacker PT, Thompson CB. Bcl-xL regulates the membrane potential and volume homeostasis of mitochondria. Cell. 1997;91:627–637. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu YT, Wolter KG, Youle RJ. Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-X(L) during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3668–3672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vander Heiden MG, Chandel NS, Li XX, Schumacker PT, Colombini M, Thompson CB. Outer mitochondrial membrane permeability can regulate coupled respiration and cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4666–4671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090082297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vander Heiden MG, Chandel NS, Schumacker PT, Thompson CB. Bcl-xL prevents cell death following growth factor withdrawal by facilitating mitochondrial ATP/ADP exchange. Mol Cell. 1999;3:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vander Heiden MG, Li XX, Gottleib E, Hill RB, Thompson CB, Colombini M. Bcl-xL promotes the open configuration of the voltage-dependent anion channel and metabolite passage through the outer mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19414–19419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam M, Bhat MB, Nunez G, Ma J, Distelhorst CW. Regulation of Bcl-xl channel activity by calcium. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17307–17310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu S, Narita M, Tsujimoto Y. Bcl-2 family proteins regulate the release of apoptogenic cytochrome c by the mitochondrial channel VDAC. Nature. 1999;399:483–487. doi: 10.1038/20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minn AJ, Kettlun CS, Liang H, Kelekar A, Vander Heiden MG, Chang BS, et al. Bcl-xL regulates apoptosis by heterodimerization-dependent and -independent mechanisms. EMBO J. 1999;18:632–643. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minn AJ, Velez P, Schendel SL, Liang H, Muchmore SW, Fesik SW, et al. Bcl-x(L) forms an ion channel in synthetic lipid membranes. Nature. 1997;385:353–357. doi: 10.1038/385353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muchmore SW, Sattler M, Liang H, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Yoon HS, et al. X-ray and NMR structure of human Bcl-xL, an inhibitor of programmed cell death. Nature. 1996;381:335–341. doi: 10.1038/381335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutter M, Fang M, Luo X, Nishijima M, Xie X, Wang X. Cardiolipin provides specificity for targeting of tBid to mitochondria. Nature Cell Biol. 2000;2:754–761. doi: 10.1038/35036395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basanez G, Zhang J, Chau BN, Maksaev GI, Frolov VA, Brandt TA, et al. Pro-apoptotic cleavage products of Bcl-xL form cytochrome c-conducting pores in pure lipid membranes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31083–31091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakey JH, van der Goot FG, Pattus F. All in the family: the toxic activity of pore-forming colicins. Toxicology. 1994;87:85–108. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.London E. Diphtheria toxin: membrane interaction and membrane translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1113:25–51. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(92)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zakharov SD, Cramer WA. Colicin crystal structures: pathways and mechanisms for colicin insertion into membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1565:333–346. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Goot FG, Gonzalez-Manas JM, Lakey JH, Pattus F. A “molten-globule” membrane-insertion intermediate of the pore-forming domain of colicin A. Nature. 1991;354:408–410. doi: 10.1038/354408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malenbaum SE, Collier RJ, London E. Membrane topography of the T domain of diphtheria toxin probed with single tryptophan mutants. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17915–17922. doi: 10.1021/bi981230h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thuduppathy GR, Hill RB. Acid destabilization of the solution conformation of Bcl-xL does not drive its pH-dependent insertion into membranes. Protein Sci. 2006 doi: 10.1110/ps.051807706. In the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lacy DB, Stevens RC. Unraveling the structures and modes of action of bacterial toxins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:778–784. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lakey JH, Gonzalez-Manas JM, van der Goot FG, Pattus F. The membrane insertion of colicins. FEBS Letters. 1992;307:26–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80895-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lesieur C, Vecsey-Semjen B, Abrami L, Fivaz M, Gisou van der Goot F. Membrane insertion: the strategies of toxins (review) Mol Membr Biol. 1997;14:45–64. doi: 10.3109/09687689709068435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeong SY, Gaume B, Lee YJ, Hsu YT, Ryu SW, Yoon SH, Youle RJ. Bcl-x(L)sequesters its C-terminal membrane anchor in soluble, cytosolic homodimers. EMBO J. 2004;23:2146–2155. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Neill JW, Manion MK, Maguire B, Hockenbery DM. BCL-XL dimerization by three-dimensional domain swapping. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:367–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd edit. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 1999. Introduction to fluorescence; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eftink MR, Ghiron CA. Exposure of tryptophanyl residues in proteins. Quantitative determination by fluorescence quenching studies. Biochemistry. 1976;15:672–680. doi: 10.1021/bi00648a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Kroon AI, Soekarjo MW, De Gier J, De Kruijff B. The role of charge and hydrophobicity in peptide–lipid interaction: a comparative study based on tryptophan fluorescence measurements combined with the use of aqueous and hydrophobic quenchers. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8229–8240. doi: 10.1021/bi00488a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 2nd edit. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 1999. Quenching of fluorescence; pp. 238–264. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beechem JM, Brand L. Time-resolved fluorescence of proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:43–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chauvin F, Toptygin D, Roseman S, Brand L. Time-resolved intrinsic fluorescence of Enzyme I. The monomer/dimer transition. Biophys Chem. 1992;44:163–173. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(92)80049-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 2nd edit. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 1999. Time-domain lifetime measurements; pp. 95–140. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolen EJ, Holloway PW. Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence by brominated phospholipid. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9638–9643. doi: 10.1021/bi00493a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gonzalez-Manas JM, Lakey JH, Pattus F. Brominated phospholipids as a tool for monitoring the membrane insertion of colicin A. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7294–7300. doi: 10.1021/bi00147a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abrams FS, London E. Calibration of the parallax fluorescence quenching method for determination of membrane penetration depth: refinement and comparison of quenching by spin-labeled and brominated lipids. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5312–5322. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ladokhin AS. Analysis of protein and peptide penetration into membranes by depth-dependent fluorescence quenching: theoretical considerations. Biophys J. 1999;76:946–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77258-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cevc G, Marsh D. Phospholipid Bilayers: Physical Principles and Models. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang M, Rigby AC, Morelli X, Grant MA, Huang G, Furie B, et al. Structural basis of membrane binding by Gla domains of vitamin K-dependent proteins. Nature Struct Biol. 2003;10:751–756. doi: 10.1038/nsb971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelsestuen GL, Ostrowski BG. Membrane association with multiple calcium ions: vitamin-K-dependent proteins, annexins and pentraxins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:433–437. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verdaguer N, Corbalan-Garcia S, Ochoa WF, Fita I, Gomez-Fernandez JC. Ca(2+) bridges the C2 membrane-binding domain of protein kinase Calpha directly to phosphatidylserine. EMBO J. 1999;18:6329–6338. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki M, Youle RJ, Tjandra N. Structure of Bax: coregulation of dimer formation and intra-cellular localization. Cell. 2000;103:645–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, et al. Differential targeting of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins by their BH3-only ligands allows complementary apoptotic function. Mol Cell. 2005;17:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Degterev A, Lugovskoy A, Cardone M, Mulley B, Wagner G, Mitchison T, Yuan J. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of interaction between the BH3 domain and Bcl-xL. Nature Cell Biol. 2001;3:173–182. doi: 10.1038/35055085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fesik SW. Promoting apoptosis as a strategy for cancer drug discovery. Nature Rev Cancer. 2005;5:876–885. doi: 10.1038/nrc1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Neill J, Manion M, Schwartz P, Hockenbery DM. Promises and challenges of targeting Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic proteins for cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1705:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Losonczi JA, Olejniczak ET, Betz SF, Harlan JE, Mack J, Fesik SW. NMR studies of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL in micelles. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11024–11033. doi: 10.1021/bi000919v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franzin CM, Choi J, Zhai D, Reed JC, Marassi FM. Structural studies of apoptosis and ion transport regulatory proteins in membranes. Magn Reson Chem. 2004;42:172–179. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cramer WA, Heymann JB, Schendel SL, Deriy BN, Cohen FS, Elkins PA, Stauffacher CV. Structure–function of the channel-forming colicins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1995;24:611–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.003143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie Z, Schendel S, Matsuyama S, Reed JC. Acidic pH promotes dimerization of Bcl-2 family proteins. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6410–6418. doi: 10.1021/bi973052i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luque I, Leavitt SA, Freire E. The linkage between protein folding and functional cooperativity: two sides of the same coin? Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:235–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Janin J, Chothia C. Role of hydrophobicity in the binding of coenzymes. Appendix Translational and rotational contribution to the free energy of dissociation. Biochemistry. 1978;17:2943294–2943298. doi: 10.1021/bi00608a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baker D, Agard DA. Influenza hemagglutinin: kinetic control of protein function. Structure. 1994;2:907–910. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swalley SE, Baker BM, Calder LJ, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Full-length influenza hemagglutinin HA2 refolds into the trimeric low-pH-induced conformation. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5902–5911. doi: 10.1021/bi049807k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matsuyama S, Llopis J, Deveraux QL, Tsien RY, Reed JC. Changes in intramitochondrial and cytosolic pH: early events that modulate caspase activation during apoptosis. Nature Cell Biol. 2000;2:318–325. doi: 10.1038/35014006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pagliari LJ, Kuwana T, Bonzon C, Newmeyer DD, Tu S, Beere HM, Green DR. The multidomain proapoptotic molecules Bax and Bak are directly activated by heat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17975–17980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506712102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McLaughlin S, Aderem A. The myristoyl-electrostatic switch: a modulator of reversible protein–membrane interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:272–276. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arbuzova A, Wang L, Wang J, Hangyas-Mihalyne G, Murray D, Honig B, McLaughlin S. Membrane binding of peptides containing both basic and aromatic residues. Experimental studies with peptides corresponding to the scaffolding region of caveolin and the effector region of MARCKS. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10330–10339. doi: 10.1021/bi001039j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seykora JT, Myat MM, Allen LA, Ravetch JV, Aderem A. Molecular determinants of the myristoyl-electrostatic switch of MARCKS. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18797–18802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim J, Blackshear PJ, Johnson JD, McLaughlin S. Phosphorylation reverses the membrane association of peptides that correspond to the basic domains of MARCKS and neuromodulin. Biophys J. 1994;67:227–237. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80473-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd edit. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carrio MM, Villaverde A. Construction and deconstruction of bacterial inclusion bodies. J Biotechnol. 2002;96:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(02)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carrio MM, Villaverde A. Protein aggregation as bacterial inclusion bodies is reversible. FEBS Letters. 2001;489:29–33. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marley J, Lu M, Bracken C. A method for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2001;20:71–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1011254402785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.MacDonald RC, MacDonald RI, Menco BP, Takeshita K, Subbarao NK, Hu LR. Small-volume extrusion apparatus for preparation of large, unilamellar vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1061:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90295-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perrin DD. Buffers of low ionic strength for spectrophotometric Pk determinations. Aust J Chem. 1963;16:572. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lehrer SS. Solute perturbation of protein fluorescence. The quenching of the tryptophyl fluorescence of model compounds and of lysozyme by iodide ion. Biochemistry. 1971;10:3254–3263. doi: 10.1021/bi00793a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wimley WC, Hristova K, Ladokhin AS, Silvestro L, Axelsen PH, White SH. Folding of beta-sheet membrane proteins: a hydrophobic hexapeptide model. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:1091–1110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.White SH, Wimley WC, Ladokhin AS, Hristova K. Protein folding in membranes: determining energetics of peptide–bilayer interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1998;295:62–87. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)95035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heymann JB, Zakharov SD, Zhang YL, Cramer WA. Characterization of electrostatic and nonelectrostatic components of protein–membrane binding interactions. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2717–2725. doi: 10.1021/bi951535l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mclaughlin S, Eisenberg M. Adsorption of alkali-metal cations to bilayer membranes containing phosphatidyl serine. Biophys J. 1979;25:A262. doi: 10.1021/bi00590a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McLaughlin S. The electrostatic properties of membranes. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1989;18:113–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Seelig J, Nebel S, Ganz P, Bruns C. Electrostatic and nonpolar peptide–membrane interactions. Lipid binding and functional properties of somatostatin analogues of charge z=+1 to z=+3 . Biochemistry. 1993;32:9714–9721. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Swanson ST, Roise D. Binding of a mitochondrial presequence to natural and artificial membranes: role of surface potential. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5746–5751. doi: 10.1021/bi00140a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lantzsch G, Binder H, Heerklotz H. Surface area per molecule in lipid/C12En membranes as seen by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Fluoresc. 1994;4:339–343. doi: 10.1007/BF01881452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kraayenhof R, Sterk GJ, Sang HW. Probing biomembrane interfacial potential and pH profiles with a new type of float-like fluorophores positioned at varying distance from the membrane surface. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10057–10066. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.