The rumbling political row over debt in the NHS means that the vexed issue of doctors' pay is not going to go away any time soon.

Are doctors in the United Kingdom overpaid? An obvious way to address the question is to compare the earnings of UK medics with those of their overseas colleagues. That is easier said than done, though: few if any direct comparisons exist, and any comparison is made difficult by different contractual agreements and working conditions. The UK Treasury has, however, made an attempt, in its latest 2007 comprehensive spending review for the NHS.

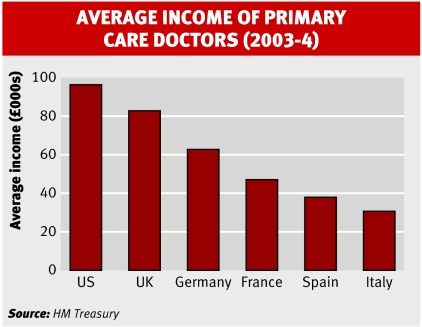

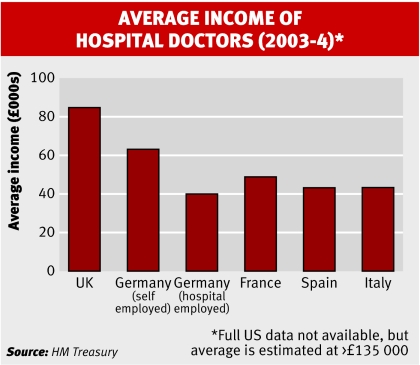

The report contains estimates of average earnings of GPs and hospital doctors in 2003-4 in 16 countries, including the UK's major competitors. The figures are based on research gathered by British embassies. It should be emphasised that the figures are estimates.

A widening gap

Nevertheless, a few things leap out from the data, including the large (and, in the case of hospital salaries, huge) lead that US doctors enjoy in pay terms. The second is the very large advantage that UK doctors have over their continental colleagues. GPs in Italy have remarkably low average earnings—the result of the marketplace being flooded with too many doctors.

Bear in mind that these are 2003 figures. The latest, very large pay rises given to UK doctors will almost certainly have widened the salary gap between British and continental doctors even further.

The Treasury report cites an average salary for GPs in the UK in 2003-4 of £82 000. The latest figures, for 2004-5, show that the average income of GPs, net of expenses, was £106 000, a rise of 30% in one year. For dispensing GPs the figure is even higher: they earned an average of £128 000 after expenses, a 31% rise.

In January the Independent newspaper reported that GPs' average earnings soared again last year (2005-6) to £118 000, according to estimates of the Association of Independent Specialist Medical Accountants. So in the three years from 2002-3, when NHS Information Centre data showed that GPs earnt on average £72 000, their earnings rose by a remarkable 63%.

As a result, the Independent noted, the average family doctor now earned, including private income, more than the Lord Chancellor, ministers of state, senior civil servants, and circuit judges.

The BMA has challenged the reliability of these figures. John Ford, the head of its economic research unit, said that the headline figures overestimate the extra amount reaching GPs' pockets, because under the new contract they must now pay employees' pension contributions.

He adds that the sample of practices used in the Independent's estimates was unrepresentative, because it included a larger than average number of dispensing practices. Also, the BMA points out that salaried GPs (who often work part time in return for a guaranteed income) earn rather less; it estimates their income to be in the region of £70 000 a year.

The headline grabbing figures of £250 000 annual earnings of a handful of GPs is, said Mr Ford, down to a few practices exploiting the potential of dispensing practices rather than being the result of the new contract.

It's not in doubt, however, that GP partners have enjoyed very large pay increases in the last three years. And inevitably the contract that has led to the “pay bonanza,” as the newspapers have called it, has come under fire. When reports of GPs earning £250 000 a year broke last year, the Sun newspaper, in an editorial entitled “Wads up doc,” said it made sense “to cap doctors' salaries and stop patients being short changed.”

Some of the broadsheets joined in. The Daily Telegraph's Simon Heffer said: “I do not doubt that many GPs work hard . . . However, equally I do not doubt that a few are royally ripping off the Government and the taxpayer thanks to the stupidity with which the Government settled its deal with their trade union.”

Renegotiations are under way

Some leading health economists, such as John Appleby of the think tank the King's Fund, say that the recent contracts are “not set in stone.” He says that behind the scene renegotiations are already under way.

In terms of the consultants' contract, ministers will be seeking to include new incentives to boost productivity rather than simply to reward the amount of time consultants spend in hospital. But the BMA says that initial predictions of the size of consultants' pay rises under their new contract have proved wide of the mark.

Between 2003-4 and 2004-5 their earnings rose by around 20% as the number of work sessions they attended rose from 10 to 12. Since then, however, Mr Ford says that rises in their salaries have stalled.

As far as GPs are concerned, ministers are keen to make performance related targets tougher. The BMA insists that the new contract had radically improved the care of patients, particularly for those with chronic diseases.

Hamish Meldrum, head of the BMA's GPs committee, said, “In the area of raised blood pressure alone, GP care under the new contract means that over a five year period 8700 patients in England will avoid having a heart attack, stroke, angina, or heart failure.”

Nevertheless, outside the BMA there is a groundswell of opinion that GPs are being too generously rewarded for providing some aspects of care that should already have been regarded as routine.

Also, other observers, such as Niall Dickson, chief executive of the King's Fund, say that the contract may actually have cut GPs' productivity by allowing the closure of Saturday morning surgeries and the ending of 24 hour cover.

The government believes that value for money and its own pride could be partially restored if family doctors were to invest more of their expanding profits back into their businesses to improve patients' care. If that's the case, say its critics, then ministers should have drawn up a contract that required this.

There is a groundswell of opinion that GPs are being too generously rewarded