Abstract

In mammalian taste buds, ionotropic P2X receptors operate in gustatory nerve endings to mediate afferent inputs. Thus, ATP secretion represents a key aspect of taste transduction. Here, we characterized individual vallate taste cells electrophysiologically and assayed their secretion of ATP with a biosensor. Among electrophysiologically distinguishable taste cells, a population was found that released ATP in a manner that was Ca2+ independent but voltage-dependent. Data from physiological and pharmacological experiments suggested that ATP was released from taste cells via specific channels, likely to be connexin or pannexin hemichannels. A small fraction of ATP-secreting taste cells responded to bitter compounds, indicating that they express taste receptors, their G-protein-coupled and downstream transduction elements. Single cell RT–PCR revealed that ATP-secreting taste cells expressed gustducin, TRPM5, PLCβ2, multiple connexins and pannexin 1. Altogether, our data indicate that tastant-responsive taste cells release the neurotransmitter ATP via a non-exocytotic mechanism dependent upon the generation of an action potential.

Keywords: ATP biosensor, ATP release, hemichannels, neurotransmission, taste cells

Introduction

Taste perception in mammals begins with the recognition of sapid molecules by specialized epithelial cells. Information transmission in the gustatory system necessitates passage of the signal from the epithelial taste cell directly to the primary gustatory fiber or indirectly via neighboring taste cells. A number of signaling molecules have been implicated in mediating the afferent neurotransmission or cell-to-cell communications in the taste bud (Roper, 2006). Among them, serotonin (E5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)) has long been considered very likely to be an afferent neurotransmitter in the peripheral taste organ. However, recent behavioral tests of wild-type versus null mice lacking the 5-HT3A subunit showed no significant differences in their responses to stimuli representative of each of the different types of taste qualities (Finger et al, 2005). These data strongly argue against the possibility that primary taste information is encoded in the form of serotonin quanta and suggest another role for serotoninergic signaling in taste bud physiology.

Previous studies have revealed the presence of ionotropic P2X2 and P2X3 receptors in gustatory nerve endings innervating taste buds (Bo et al, 1999) and taste cell-specific expression of P2Y receptors coupled to Ca2+ mobilization (Kim et al, 2000; Baryshnikov et al, 2003; Kataoka et al, 2004; Bystrova et al, 2006). The physiological roles for gustatory P2 purinoceptors have not yet been determined precisely, but by analogy with other tissues, their involvement in diverse taste cell functions has been hypothesized. Recent studies of P2X2/P2X3 double knockout mice have provided fundamental insights into the role of purinergic signaling in taste bud physiology (Finger et al, 2005): the double knock-out mice lacked all neuronal responses to taste stimuli of all qualities and had dramatically reduced behavioral responses to sweet, bitter, and umami substances. The clear inference is that ATP may serve as the afferent neurotransmitter to mediate taste signal output to gustatory nerve endings. Consistent with such a role is the observation that bitter substances stimulate ATP secretion from lingual epithelium containing taste cells (Finger et al, 2005): however, the cellular origin and underlying mechanisms of ATP release from taste cells have not yet been determined.

Here, we studied ATP release from mouse taste cells using an ATP biosensor. This general method has been successfully used to monitor secretion of various neuroactive substances from cells of several types (Tachibana and Okada, 1991; Morimoto et al, 1995; Savchenko et al, 1997), including efflux of ATP from macula densa cells (Bell et al, 2003). Moreover, the release of serotonin from mouse taste cells has been documented recently using CHO cells transfected with 5-HT2C receptors (Huang et al, 2005). Individual mouse taste cells exhibit specific sets of voltage-gated (VG) currents whereby they can be reliably distinguished and classified into three major physiologically defined subcategories: A, B, and C (Romanov and Kolesnikov 2006). Recently determined functional and morphological properties of taste cell types associated with the presence of specific markers (Medler et al, 2003; Clapp et al, 2006; De Fazio et al, 2006; present work) enable us to correlate the electrophysiologically defined taste cell types with conventional morphologically defined cell types as follows: type A=type II, type B=type III, and type C=type I. A specific aim of this study was to determine if ATP secretion is the hallmark of any specific taste cell type.

Results

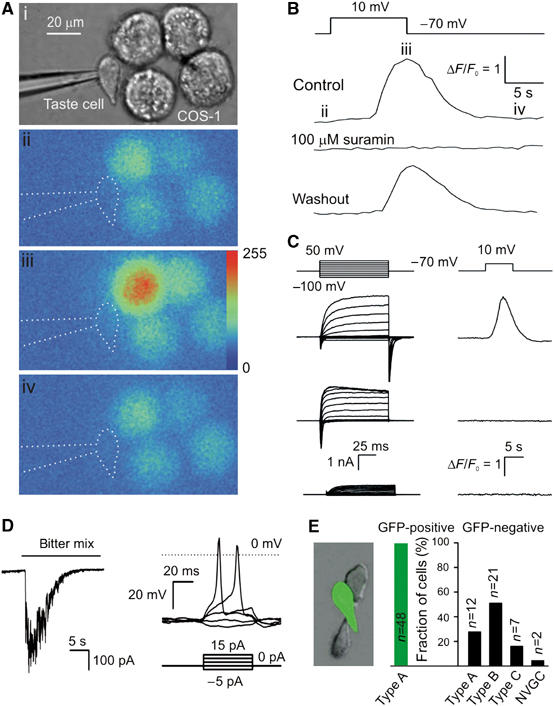

Individual electrophysiologically identified taste cells, isolated from mouse circumvallate (CV) papillae, were assayed for release of ATP using COS-1 ATP-biosensor cells (Figure 1A). The COS-1 biosensors, loaded with the Fluo-4 Ca2+ indicator to monitor a local rise in extracellular ATP with Ca2+ transients, were sensitive to ATP, as they endogenously expressed P2Y receptors coupled to Ca2+ mobilization. An advantage of using P2Y receptors over P2X receptors (Bell et al, 2003) was that removal of external Ca2+ affected ATP responses of our biosensors only weakly, enabling us to examine the coupling of Ca2+ influx to ATP secretion with Ca2+ imaging. Because taste cells might release more than one transmitter (Roper, 2006), control experiments were performed to examine the responsiveness of COS-1 cells to several neuroactive compounds: serotonin, glutamate, acetylcholine (ACh), and γ-aminobutyric acid. Of these compounds, only 40 μM ACh evoked detectable responses; however, they were quite small compared with those elicited by 1 μM ATP (see Supplementary data I and Supplementary Figure 1). The other compounds tested (at 20 μM) had no significant effect on the intracellular Ca2+ responses of the biosensor. Suramin (100 μM), a nonspecific P2 receptor antagonist, inhibited Ca2+ transients triggered by 1 μM ATP by ∼90%. Thus, COS-1 cells exhibit both high specificity and high sensitivity (100 nM) to ATP to serve as effective biosensors.

Figure 1.

Release of ATP from taste cells. (A) Assay of ATP secretion with an ATP biosensor. (i) Simultaneous recording from the patch-clamped taste cell and COS-1 cell biosensors loaded with Fluo-4. (ii–iv) Sequential fluorescent images of the COS-1 cells in control (ii) and after depolarization of the taste cell to 10 mV (iii, iv). Color palette in (iii) shows the pixel intensity mapping (range: 0–255, 8-bit data). (B) A relative change in Fluo-4 fluorescence recorded from the upper-left COS-1 cell in (Ai) triggered by taste cell depolarization (upper inset). The images (ii–iv) in (A) were captured at the time points indicated by the letters above the upper trace. The middle and bottom traces represent responses of the same COS-1 cell in the presence of 100 μM suramin and after washout. (C) Correlations between electrophysiological characteristics of taste cells (left panels) and their ability to release ATP (right panels). Only taste cells exhibiting integral currents of type A (upper-left traces) secreted ATP upon depolarization, whereas cells with type B (middle-left traces) or type C (bottom-left traces) currents never stimulated the ATP sensor upon depolarization. The upper insets indicate command voltage used for cell identification (left panel) and for the stimulation of ATP release (right panel). (D) Left panel: a type A cell held at −70 mV generated an inward current of about 400 pA in response to the bitter mix. Right panel: type A cells are electrically excitable. Typically (n=14), inward currents elicited action potentials (APs) with the threshold of 10–15 pA, suggesting generator currents (left panel) to produce APs. (E) Taste cells isolated from GFP-transgenic mice (left panel). As shown in the right panel, all gustducin-positive (green) cells (n=48) exhibited integral currents of A type, whereas the population of gustducin-negative (dark) cells (n=42) contain all electrophysiologically defined subtypes. The numbers of tested cells are indicated above the bars. In all cases, currents/voltage were recorded with 140 mM KCl in the pipette and 140 mM NaCl in the bath using the perforated patch approach.

When taste cells were held at −70 mV, adjacent COS-1 ATP-biosensor cells generated no Ca2+ signals. However, depolarization of the taste cell above −10 mV stimulated Ca2+ mobilization in a nearby COS-1 cell (Figure 1Aii–iv and B) with a delay of 3–10 s, depending on the distance between the taste cells and the biosensor. Suppression of the biosensor Ca2+ responses by suramin (100 μM) (Figure 1B) confirmed the purinergic nature of the signal released by taste cells and detected by COS-1 cells. Thus, the electrical stimulation of taste cells led to a rise in ATP in close vicinity to the biosensor.

ATP is released by specific types of taste cells

As noted above, mouse taste cells can be categorized by their electrophysiological properties and the molecular markers they express. The cell type-specific sets of VG currents displayed in the left panel of Figure 1C exemplify those designated by us as A (II), B (III), and C (I) types (upper, middle, and bottom traces, respectively—with conventional morphologic type I, II, III definitions indicated in parentheses). Whereas most type A cells (81%, n=25) released ATP in response to depolarization, ATP efflux from robust cells of type B (n=11) or type C (n=5) was never detected under our recording conditions (Figure 1C, right panel). Thus, in CV taste buds, only type A cells release ATP in response to depolarization. Taste cells isolated from foliate papillae behaved similarly: five of five foliate type A cells assayed released ATP upon depolarization; none of the foliate type B cells (n=3) or type C cells (n=2) released ATP (not shown).

The dramatic loss of taste responsiveness documented for P2X2/P2X3 double knock-out mice (Finger et al, 2005) indicates that afferent signal output is entirely dependent upon extracellular ATP. Thus, ATP-secreting type A (II) taste cells may represent a population of primary chemoreceptive cells. To test this, we recorded from type A CV cells (n=91) that were stimulated by a mix of bitter compounds (100 μM cycloheximide+1 mM denatonium benzoate+3 mM sucrose octaacetate). Responsiveness of dissociated taste cells was rather low: five of 91 type A cells (5.5%) were responsive to the tastants (Figure 1D, left panel). This compares well to the value of 3% responsive cells noted by De Fazio et al (2006). Despite the typical low response rate, these experiments demonstrate that type A cells do indeed respond to taste stimuli. Furthermore, none of the type B cells (n=73) or type C cells (n=16) responded to the bitter mix with a visible change in the resting current (not shown).

With a high-input resistance of about 1 GΩ, the taste-related generator currents of 50–400 pA should be large enough to electrically excite type A cells so as to effect ATP secretion (Figure 1D, right panel). In an attempt to directly confirm this idea, taste cells that released ATP upon depolarization were also assayed with the current clamp approach (n=17): however, upon stimulation with the bitter mix, none of these cells depolarized and/or released ATP (not shown). The generally low responsiveness of individual taste cells may contribute, in part, to our failure to observe the expected linkage. Probably a more important factor is that the effective extracellular volume in the bath where released ATP diffuses before reaching the biosensor exceeds that in the taste bud by a factor of 102–103. This rough estimate indicates that in our setup, ATP undergoes ∼100-fold or more dilution and likely accounted for why taste cell depolarization of at least 500 ms was typically required for us to be able to detect ATP release. Therefore, even if a taste cell generated a taste response with action potentials (APs), it would have been insufficient to release enough ATP to stimulate the ATP sensor. When taste cells (n=5) were repeatedly depolarized with AP-like pulses, a series of 150–190 spikes was required to provide ATP release sufficient to be detectable (Supplementary Figure 2). Extrapolating this result to the situation in vivo, we calculate that to elevate ATP in media between neighboring taste cells to about this same level (i.e. detectable with the ATP sensor) would require an upper limit of <1.9 spikes (i.e. n=190 spikes/(dilution factor >100)). This estimation clearly demonstrates that in situ a single AP can release enough ATP to stimulate a gustatory nerve ending.

Type II cells, initially defined by their ultrastructural appearance, are believed to be sensory cells as they express the entire taste transduction machinery, including G-protein-coupled taste receptors, the heterotrimeric G-protein gustducin, phospholipase Cβ2 (PLCβ2), and the cation channel TRPM5 (Scott, 2004). If VG currents of the type A classification (Figure 1C, upper-left panel) are indeed inherent in chemosensory cells, then type A taste cells should express these several signaling proteins. In several experiments, we recorded from taste cells isolated from transgenic mice that expressed a GFP transgene from the gustducin promoter (Wong et al, 1999; Medler et al, 2003). Gustducin-positive taste cells, a subset of type II cells, were well identifiable owing to their green fluorescence (Figure 1E, left panel). All 48 green cells displayed VG currents characteristic of the type A family (i.e. Figure 1C, upper-left traces), thus demonstrating that the gustducin-positive type II cells fall into the A subgroup of electrophysiologically defined taste cells (Figure 1E, right panel). In contrast, among gustducin-negative (i.e. non-green) cells (n=42), all electrophysiologically defined cell types were seen, including a small fraction of cells that showed no VG currents (Figure 1E, right panel). Thus, the cell category A includes gustducin-positive cells as a subgroup (64%; Supplementary data III).

TRPM5 is a Ca2+-gated cation channel expressed in apparently all type II cells. Because TRPM5-specific blockers are not available, we inferred their presence in subtypes of taste cells based on electrophysiological measurements. Several groups have studied the Ca2+ dependence of TRPM5 and reported different half-effect concentrations and Hill coefficients: K0.5=21 μM and n=2.4 (Liu and Liman, 2003), K0.5=840 nM and n=5 (Prawitt et al, 2003), and K0.5=700 nM and n=6.1 (Ullrich et al, 2005). Nevertheless, they all give a fraction of open TRPM5 channels at resting Ca2+ (70 nM; Kim et al, 2000) of about 10−6, suggesting negligible activity of TRPM5 channels in unstimulated taste cells. To activate TRPM5, intracellular Ca2+ was elevated with the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (1–2 μM); this increased the ion permeability of type A cells. However, the small gain of 10–25% complicated the unequivocal identification of Ca2+-dependent currents in the presence of large VG currents that varied with time (not shown). In searching for more optimal recording conditions, we found that in unstimulated cells, the PLC inhibitor U73122 (5 μM) produced a relatively fast and virtually irreversible inhibition of the VG currents (Figure 2A). The mode of action of this inhibition is currently unknown, but it enabled us to isolate an ionomycin-stimulated (IS) current and to generate its I–V curves with precision under different conditions.

Figure 2.

TRPM5-like cation channels operate in type A cells. (A) Evolution trace for outward currents in the presence of 5 μM U73122 (•) (n=7) and 15 μM U73343 (○) (n=4), a less potent PLC inhibitor, exhibited half-inhibition times of about 2.5 and 11 min, respectively. The VG currents were recorded from type A cells at 50 mV and normalized to the value obtained immediately before drug application. (B) Effects exerted by 5 μM U7312 and 1 μM ionomycin on the resting currents recorded at −70 mV with 140 mM NaCl or 140 mM NMDGCl in the bath (n=11). The short current transients were produced by cell polarization with the voltage ramp from −80 to 80 mV (1 mV/ms) to generate the I–V curves presented in (C). (C) Left panel: I–V curves generated before (1) and 4 min after (2) U73122 application. Middle panel: with VG outward currents inhibited (3 and 4), an increase in membrane permeability (5 and 6) produced by ionomycin was well resolved. Right panel: the substitution of external NaCl for NMDGCl negatively shifted the reversal potential of the ionomycin-stimulated (IS) current from −2 to −54 mV. The IS current was calculated as the difference between currents recorded before and after ionomycin application (5–4 and 6–3). (D) Upper trace: a drop in bath temperature strongly (Q10=4.7) suppressed the IS current. Bottom trace: bath temperature in control (24.5°C) and during application and removal of cooled bath solution. (E) I–V curves were generated at the time points indicated in (D) at two different temperatures before (1 and 2) and after application of 2 μM ionomycin (3 and 4). In the inset, ratio It/I25 versus temperature; It and I25 are IS currents at −80 mV and at temperatures t and 25°C, respectively. The line regression of the data from five different cells yielded the slope of 4.7. In (A), the recording conditions were as in Figure 1E. In (B–D), cells were dialyzed with the intracellular Cs+ solution containing 1 mM EGTA and perfused with the Na+ bath solution.

In type A cells that were pretreated with U73122 and held at −70 mV, ionomycin elicited a well-resolved inward current (Figure 2B), accompanied by a strong increase in membrane conductance (Figure 2C). With 140 mM NaCl in the bath and 140 mM CsCl in the pipette, IS currents reversed at nearly zero voltage (n=11) (Figure 2C, curves 4, 5, and 5-4), indicating that either the responsible channels are selective for anions or they are equally permeable to Na+ and Cs+. The substitution of external Na+ for NMDG+ that is impermeable to cation-selective channels including TRPM5 (Liu and Liman, 2003; Prawitt et al, 2003) shifted the reversal potential to −55–60 mV (n=4) (Figure 2B and C, curves 3, 6, and 6-3). These results verified the cation selectivity of the channels involved and indicated that Na+ and Cs+ do permeate them equally well, as is the case with the TRPM5 channel (Liu and Liman, 2003; Prawitt et al, 2003). In addition, the IS currents were strongly enhanced by an increase in the bath temperature, showing Q10=4.7±0.6 (n=5) (Figure 2D and E). Thus, both the IS channels and the TRPM5 channels are characterized by similar selectivity and prominent outward rectification (Figure 2C) (Liu and Liman, 2003) and by high thermosensitivity (Figure 2E) (Talavera et al, 2005), features suggesting their identity. Notably, the TRPM5-like cation channels were specific for type A cells: ionomycin stimulated a Ca2+-gated Cl− current in type C cells (Kim et al, 2000) and no current in type B cells (data not shown).

Mechanism of ATP release

Release of ATP from taste cells might employ exocytosis driven by a local rise in intracellular Ca2+ (Fossier et al, 1999), ABC transporters, or ATP-permeable ion channels (Bodin and Burnstock, 2001; Lazarowski et al, 2003). When the intracellular Ca2+ trigger was eliminated both by decreasing extracellular Ca2+ to 100 nM (n=9) and by loading type A cells with the fast Ca2+ chelator BAPTA (10 mM) (n=4), the ATP secretion was not affected significantly (Figure 3A). These observations argue against a vesicular mechanism, suggesting instead that ATP was released from taste cells via VG channels.

Figure 3.

ATP is released from taste cells via channels. (A) ATP secretion triggered by depolarization (upper insets) was apparently independent of Ca2+. Upper traces: ATP release from the same cell was weakly dependent on extracellular Ca2+. Bottom traces: ATP secretion from the same cell was not diminished by dialysis with 10 mM BAPTA (left panel) or by the drop in extracellular Ca2+ (right panel). The patch pipette contained 140 mM CsCl, 2 mM K2ATP, and 10 mM BAPTA. (B) Responses of the ATP sensor to serial depolarization of a taste cell to specific potentials (indicated above the traces) for 5 s. (C) ATP responses (Δ) of COS-1 cells as a function of taste cell depolarization from −70 mV to indicated voltage for 5 s. The responses of the ATP sensor correlate well with the integral conductance G of taste cells (•) calculated by the equation I=G(V−Vr), where I, V, and Vr are sustained current, membrane voltage, and reversal potential, respectively. The data are presented as mean±s.d. (n=3–7). In (A (upper trace), B, C), the recording conditions were as in Figure 1E.

Serial depolarization of ATP-secreting taste cells typically elicited multiple and highly reproducible responses of the ATP sensor (n=9) (Figure 3B), demonstrating the high fidelity of the secretory machinery. As a function of membrane voltage, ATP efflux correlated nicely with the integral conductance and showed a steep dependence on cell polarization (Figure 3C), inconsistent with the weakly rectifying I–V curves characteristic of ABC transporters (Abraham et al, 1993). On the other hand, a number of ion channels with markedly nonlinear I–V curves have been reported to mediate ATP secretion in a variety of different cells; examples include certain anion channels (Hazama et al, 2000; Sabirov et al, 2001; Bell et al, 2003), connexin (Cotrina et al, 1998; Stout et al, 2002), and pannexin (Bao et al, 2004; Locovei et al, 2006) hemichannels. Given that BzATP (100 μM) never elicited an inward current at −70 mV (n=5) (not shown), P2X7 receptors recently implicated in ATP release from astrocytes (Suadicani et al, 2006) are not operative in type A cells. We therefore focused on the other channels as potential mediators of ATP efflux from taste cells.

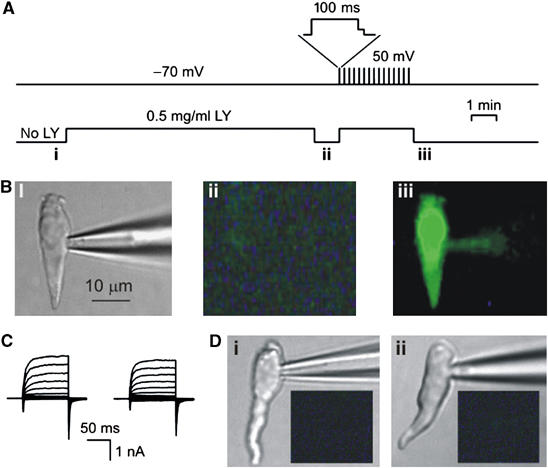

Channels formed by connexins (Cxs) and pannexins (Pxs) are weakly selective and permeable to a variety of compounds, including polar tracers (Bennett et al, 2003; Goodenough and Paul, 2003; Locovei et al, 2006). We studied the accumulation of Lucifer Yellow (LY) by taste cells as an indicator of the presence of functional hemichannels. An identified taste cell was incubated with LY (0.5 mg/ml) at −70 mV for 10 min (Figure 4A). The dye was removed from the bath and LY loading was assessed by imaging. Irrespective of taste cell type, none of 12 tested cells exhibited specific fluorescence, demonstrating that LY does not permeate through the highly hyperpolarized plasma membrane (Figure 4Bii). In the next protocol, LY was again added to the bath and the cell was periodically (0.16 Hz) depolarized to 50 mV for 100 ms during a 3-min interval that was followed by LY washout and optical recording (Figure 4A). Five type A cells were tested and all of them exhibited bright fluorescence at the end of the loading protocol (Figure 4Biii). The consequent electrophysiological recordings (Figure 4C) revealed no damage of the plasma membrane, implicating a specific pathway for LY accumulation. This loading of type A cells was highly specific: type B cells (n=4) (Figure 4Di) and type C cells (n=3) (Figure 4Dii) never took up LY under this same loading protocol. Similar results were obtained with taste cell loading of 1 mM carboxyfluorescein (not shown). These results indicate that hemichannels operate in type A cells but not other types of taste cells. However, these loading experiments do not rule out the possibility that anion channels may also be involved in ATP secretion.

Figure 4.

Accumulation of Lucifer Yellow (LY) by taste cells. (A) Protocol of cell loading with LY. Upper trace: taste cell polarization with time; after the depolarization to 50 mV, cells were repolarized in two steps (upper inset) to reduce the efflux of negatively charged LY through deactivating channels. Bottom trace: LY concentration in the bath. (B) Type A cell viewed in transparent light before LY application (i) and in epifluorescence during LY loading at −70 mV (ii), and after the serial depolarization (iii). The fluorescent images were captured with a 535±25 nm optical filter at the time points marked with the letters below the bottom trace in (A). (C) WC currents recorded from the cell presented in (D) before (left panel) and after (right panel) loading with LY. The recording conditions were as in Figure 1E. (D) Taste cells of the B (i) and C (ii) types did not take up LY on serial depolarization (C), as demonstrated by the fluorescent images (dark insets) captured as in (Biii). In (Bii, Ci, Cii), the images were acquired with exposition twice longer than in (Biii).

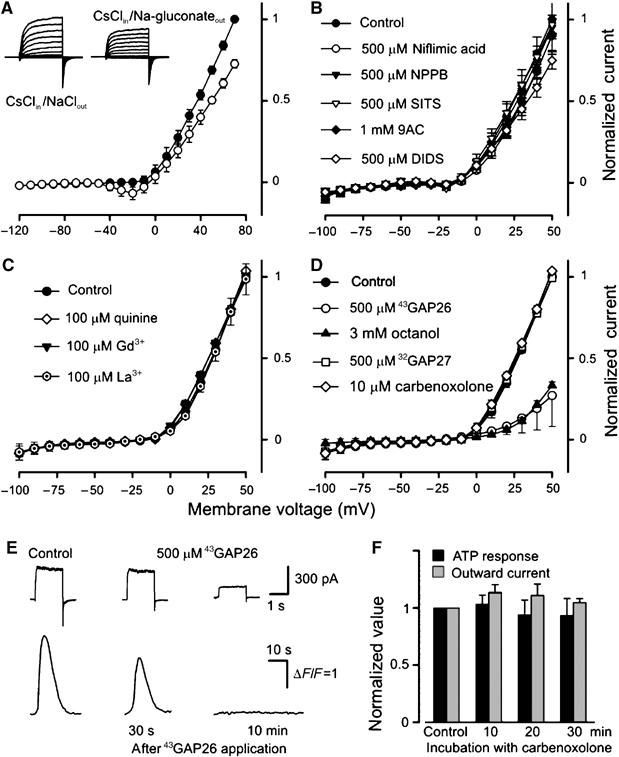

When extracellular Cl− was replaced with the poorly permeating gluconate (e.g. Mignen et al, 2000), the reversal potential of the integral current was shifted positively from −36±3 mV in control (n=28) to −5±2 mV (n=6) (Figure 5A). Such a shift indicated that the plasma membrane was well permeable to Cl− ions. However, various blockers of anion channels at concentrations at which they would markedly inhibit a variety of Cl− channels (Hume et al, 2000) exerted no effects or only slight effects on the integral currents (Figure 5B). ATP release was generally unaffected by these compounds (not shown). These observations argue against anion channels, thus favoring hemichannels as the predominant transport pathway for the Cl− and ATP3− anions in type A cells.

Figure 5.

Pharmacology of outward currents and ATP release. (A) Substitution of 140 mM NaCl (•) for 140 mM Na-gluconate (○) in the bath shifted the reversal potential of sustained integral currents positively. (B–D) Effects of bath application of Cl− channel blockers (B) and hemichannel inhibitors (C, D) on sustained integral currents (n=3–7). As shown in (D), only octanol (3 mM) (▴) and the connexin mimetic peptide 43GAP26 (500 μM) (○) caused significant current inhibition. The I–V curves in the presence of 43GAP26 and carbenoxolone were generated 10 and 30 min after drug application, respectively. The data are presented as means±s.d. (E) 43GAP26 (500 μM) inhibited reciprocally both the outward currents (upper panel) and the ATP sensor responses (bottom panel) elicited by the serial depolarization of a taste cell from −70 to 10 mV. (F) Both outward currents and ATP release were weakly sensitive to 10 μM carbenoxolone. In all cases, taste cells were assayed by using the perforated patch approach with 140 mM CsCl in the recording pipette and with 140 mM NaCl in the bath.

To characterize the pharmacological profile of the hemichannels involved, we tested a number of compounds known to inhibit the activity of certain hemi- and junctional channels, including lanthanides (Braet et al, 2003), quinine (Srinivas et al, 2001), octanol, and some anion channel blockers (Eskandari et al, 2002). As was the case with niflumic acid and NPPB (both at 0.5 mM) (Figure 5B), La3+, Gd3+ (both at 100 μM), and quinine (1 mM) affected the outward currents only weakly or not at all (Figure 5C). Octanol (3 mM) suppressed the outward currents profoundly (Figure 5D).

We also used the connexin mimetic peptides 32GAP27 and 43GAP26 (both at 500 μM), which have been implicated in the inhibition of ATP release mediated by Cx32 and Cx43 hemichannels, respectively (Chaytor et al, 1997, 2001; Leybaert et al, 2003; De Vuyst et al, 2006). Whereas 32GAP27 was ineffective, 43GAP26 dramatically reduced the outward currents (Figure 5D). In theory, the hemichannels responsible for ATP efflux might carry only a small fraction of the outward currents. We, therefore, examined effects of the hemichannel inhibitors on ATP release as well. When ATP efflux was assayed (Figure 1A) in the presence of 43GAP26, this mimetic peptide, within 5–15 min, inhibited both the outward currents and the Ca2+ responses of the ATP sensor (n=5) (Figure 5E). The effects of 43GAP26 appeared to be specific because (i) 43GAP26 per se never inhibited COS-1 responses to control applications of ATP (n=4) (not shown), (ii) with no 43GAP26 in the bath, taste cells showed reproducible ATP release upon serial stimulation for up to 30 min (Figure 3B), and (iii) 32GAP27 (0.5 mM) eliminated neither outward currents (Figure 5D) nor ATP release (n=3) (not shown).

Carbenoxolone has been shown to exert a slow inhibition of hemichannels with much higher efficacy for Px1 over Cx46 (at 10 μM, effecting 55 and 7% inhibition of Px1 and Cx46 hemichannels, respectively; Bruzzone et al, 2005). Carbenoxolone at 10 μM for up to 30 min had no significant effect on VG outward currents (Figure 5D and F). As an antagonist of ATP release, 10 μM carbenoxolone was also ineffective (Figure 5F). These observations suggest that if involved, Px1 hemichannels transport only a small fraction of the VG currents and ATP efflux. Furthermore, currents mediated by recombinant Px1 and the VG outward current in type A cells are very different in their kinetics: the former exhibits fast activation and strong inactivation (Bruzzone et al, 2005), whereas the latter is slowly activating and non-inactivating (Figure 1C, upper-left panel). Thus, the above observations (Figures 3 and 5) argue most strongly in favor of connexin hemichannels in mediating both the VG outward currents and the depolarization-elicited ATP secretion.

Molecular identity of hemichannels

Among the several mammalian connexins (Cruciani and Mikalsen, 2006) and three pannexins (Panchin et al, 2000), only Cxs26, Cxs30, Cxs32 and Cxs43 (Stout et al, 2002; Tran Van Nhieu et al, 2003), and Px1 (Locovei et al, 2006) have been implicated in mediating ATP release. In taste tissue, only Cx43 had been identified previously (Kim et al, 2005).

That the mimetic peptide 43GAP26 inhibited VG outward currents and ATP release (Figure 5G), whereas 32GAP27 was ineffective, argues in favor of Cx43. Some features of expressed Cx43 hemichannels are consistent with the VG channels we have observed to mediate outwardly rectifying currents in type A taste cells (Figure 1C). However, recombinant Cx43 connexons are blocked by NPPB (100 μM), La3+ (200 μM), and Gd3+ (150 μM) (Braet et al, 2003)—findings that are inconsistent with Cx43 alone mediating outward currents and ATP release in type A taste cells (Figure 5B and E). Potentially, Cx43 and other connexins might form a heteromultimeric hemichannel that is less sensitive to lanthanides and NPPB than are hemichannels made of Cx43 alone. Still, such channels would have to be inhibited by 43GAP26. Alternatively, 43GAP26 might also inhibit connexins that contain the SHVR amino-acid motif in the first extracellular loop, the structural element presumably responsible for the inhibitory effects of 43GAP26 on Cx43 (Warner et al, 1995). Mouse Cxs30.3, Cxs31.1, Cxs32, Cxs33, Cxs45, and Cxs47 satisfy this criterion, although to our knowledge, their sensitivity to 43GAP26 has never been studied. We therefore searched for the presence in CV papillae RNA of transcripts for these connexins, Cx43, Cx26, Cx32, and Px1. With the exception of Cx32 and Cx47, signals for all of the above were detected in the taste tissue by RT–PCR with gene-specific primers (not shown). Given, however, that these taste tissue preparations contain multiple types of taste cells along with epithelial cells, the identity of the cells expressing connexins and/or Px1 is uncertain.

To address this problem, we identified 10 type A cells, sucked each cell with the patch pipette, and expelled the cellular material into the same tube for linear RNA amplification (Van Gelder et al, 1990) and PCR analysis. Using these combined techniques, we were able to detect mRNA transcripts for PLCβ2 and TRPM5 (Figure 6A), a result expected for type A (II) cells that validated our physiological and molecular methodology. In addition, messages for Cxs26, Cxs30.3, Cxs31.1, Cxs33, Cxs43, and Px1 were also found in type A cells (Figure 6A). We also carried out in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry to examine expression of some of these elements in taste cells. In agreement with the PCR data, double immunostaining of CV papilla sections with antibodies against Px1, PLCβ2, and TRPM5 revealed Px1 immunoreactivity in all PLCβ2/TRPM5-positive cells and rarely in PLCβ2/TRPM5-negative cells (Figure 6B and C), that is, Px1 is expressed in type A (II) cells but not in other types of taste cells. By in situ hybridization, we also observed the presence of Px1 and Cx43 in taste cells (not shown). Thus, taste cells of type A express multiple junctional proteins that may mediate diverse signaling processes, including ATP secretion. Physiological functions in type A taste cells for each expressed connexin and Px1 remain to be determined.

Figure 6.

Expression of signaling and junctional proteins in taste cells. (A) Linear RNA amplification and PCR analysis of the indicated gene transcripts in a preparation of single cells of type A. The expected amplification products were obtained for Cx26, Cx30.3, Cx31.1, Cx33, Cx36, Cx43, Px1, TRPM5, and PLCβ2. Transcripts for Cx 32 (lane 4), Cx 45 (lane 8), and Cx 47 (lane 9) were not detected, although relevant products were amplified in control preparations of the brain (not shown). Molecular weight markers (M) from Gene Ruler 1-kb ladder (Fermentas). The 1.4% agarose gels were stained with ethidium bromide. (B, C) Confocal images of mouse circumvallate taste buds double labeled with antibodies against Px1 (green) and PLCβ2 or TRPM5 (red). Right panels show the merged images indicating the significant overlap in expression (yellow–orange) of Px1 with PLCβ2 and/or TRPM5 in type II taste cells.

Discussion

Purines have long been recognized as first messengers involved in the neurotransmission and autocrine/paracrine regulation of cellular functions (Burnstock, 2001; Lazarowski et al, 2003). The recent demonstration that P2X and P2Y receptors and ecto-nucleosidases operate in the mammalian taste bud suggests an important role for purinergic signaling in the physiology of the peripheral taste organ (Bo et al, 1999; Baryshnikov et al, 2003; Bartel et al, 2006; Bystrova et al, 2006). The findings of Finger et al (2005) have demonstrated that afferent output from taste buds is entirely dependent on extracellular ATP. The secretion of ATP may therefore be expected to be an important aspect of taste transduction.

Here, we studied ATP release from individual taste cells that were classified electrophysiologically into types A, B, and C (Romanov and Kolesnikov, 2006). We found that only type A cells were capable of secreting ATP (Figure 1C). Data from physiological and pharmacological experiments argued against an exocytotic mechanism, favoring instead a hemichannel-mediated mechanism for ATP efflux from taste cells. Type A cells were found to express TRPM5, PLCβ2 (both markers for type II cells), multiple connexins, and Px1.

A number of signaling molecules crucial for taste transduction have been identified in taste cells morphologically defined as type II cells, suggesting that this cell type serves as primary sensory receptor cells (Scott, 2004). As demonstrated by recent studies with transgenic mice, wherein taste cells expressing a particular protein were genetically tagged with GFP (Medler et al, 2003; Clapp et al, 2006), type II cells that express gustducin, TRPM5, and the T1R3 taste receptor exhibit VG Na+ currents but no VG Ca2+ currents. Consistent with this observation, De Fazio et al (2006) found no RNA messages for VG Ca2+ channels in PLCβ2-positive cells. Such functional and molecular features are also characteristic of type A cells: (i) VG Na+ channels and no VG Ca2+ channels operate in these cells (Romanov and Kolesnikov (2006); (ii) type A cells express gustducin, PLCβ2, and TRPM5 signaling proteins (Figures 1E and 6); and (iii) type A cells are responsive to tastants (Figure 1D) and release ATP (Figure 1C), the most likely afferent neurotransmitter (Finger et al, 2005). In addition, the secretion of ATP via hemichannels is completely consistent with the fact that type II cells do not form morphologically identifiable synapses (Clapp et al, 2004) and do not express the presynaptic protein SNAP-25 (Clapp et al, 2006; De Fazio et al, 2006). It therefore appears that the cellular subgroups, one defined electrophysiologically (type A) and another morphologically (type II), overlap greatly or even completely.

Extracellular recordings have demonstrated that mammalian taste cells, which do not send axonal projections directly to the brain or to intermediate neuronal cells, may generate an AP in response to taste stimuli (Avenet and Lindemann, 1991; Cummings et al, 1993). Although the conventional point of view is that the AP is necessary to drive the release of neurotransmitter onto the afferent nerve (e.g. Herness and Gilbertson, 1999), there is no experimental evidence in favor of this idea. Moreover, in retinal rods and cones and in auditory hair cells, which all have no axons, light and sounds, respectively, elicit generator potentials that govern the tonic release of glutamate without presynaptic APs (Sterling and Matthews, 2005). Our findings may explain why sensory cells in the taste bud generate APs.

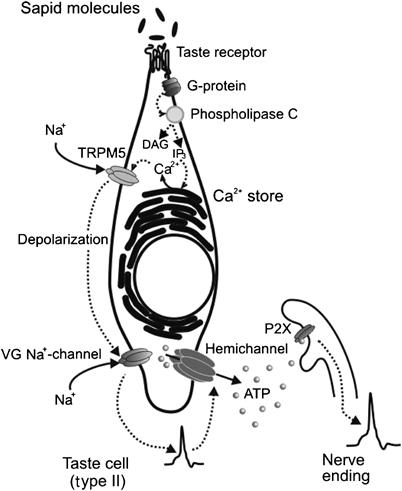

In our experiments, the resting potential in type A cells ranged from −53 to −36 mV (−43±3 mV, n=41) with 140 mM KCl in the recording pipette and 140 mM NaCl in the bath (not shown). A similar value (∼−45 mV) was obtained by Medler et al (2003) for mouse taste cells that showed VG Na+ currents and no VG Ca2+ currents, that is, type A cells. These estimates suggest that the fraction of non-inactivated VG Na+ channels in resting type A cells is high enough to generate APs in response to tastants (Figure 1D). Characteristic of the ATP secretion are the steep dependence on membrane voltage and the high apparent threshold of about −10 mV (Figure 3C). If taste stimuli evoked gradual depolarization without AP as their intensity increased, then small and moderate responses of up to 30 mV would fail to stimulate ATP release. The likely voltage range, where ATP secretion might occur, would be between −10 and 0 mV, provided that a generator current is mediated by transduction channels such as the TRPM5 cation channel (Figure 2C). Thus, with the secretory mechanism described graded taste responses seem inappropriate for taste information encoding. In contrast, every AP that might be triggered by moderate depolarization above the threshold of about –40 to −35 mV (Figure 1D, right panel) would stimulate the release of a more or less universal ATP quantum (Figure 3C). With this all-or-nothing strategy, encoding of taste information is reduced to the generation of APs in series with frequency being proportional to stimulus intensity. Thus, based on our findings and given the current concept on taste transduction (Scott, 2004; Roper, 2006), we hypothesize that the binding of sapid molecules may trigger the sequence of intracellular events depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic model showing the hypothetical sequence of intracellular events that are triggered by the binding of sapid molecules to taste receptors and culminate in ATP release through hemichannels.

Materials and methods

Electrophysiology

Taste cells were isolated from mouse (NMRI, 6–8-week old) CV and foliate papilla as described previously (Baryshnikov et al, 2003). Ion currents were recorded, filtered, and analyzed using an Axopatch 200A amplifier, a DigiData 1200 interface, and the pClamp8 software (Axon Instruments). External solutions were delivered by a gravity-driven perfusion system at a rate of 0.1 ml/s. VG currents were elicited by 100 ms step polarizations from the holding potential of −70 mV. For whole-cell recordings, patch pipettes were filled with (mM) 140 KCl or CsCl, 2 MgATP, 0.5 EGTA or 10 mM BAPTA, and 10 HEPES–KOH (pH 7.2). For perforated patch recordings, recording pipettes contained (mM) 140 KCl or 140 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 10 HEPES–KOH (CsOH) (pH 7.2), and 400 μg/ml amphotericin B. The basic bath solution included (mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES–NaOH (pH 7.4), and 5 glucose. It was modified in that 140 mM NaCl was substituted for 140 mM sodium gluconate or in that 1 mM Ca2+ was replaced with 1 mM EGTA+0.59 mM Ca2+ ([Ca2+]free∼100 nM). BAPTA, U73122, and U73343 were from Calbiochem; all other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich. Experiments were carried out at 23–25°C.

Cell culture

The COS-1 cell line was routinely maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogene) containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (Hi Clone), glutamine (1%), and the antibiotics penicillin (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (all supplements from Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were grown in 35-mm-diameter dishes in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2/95% O2) at 37°C. Cells were suspended in Hanks's solution containing 0.25% trypsin and collected in a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube after terminating the reaction with 2% fetal bovine serum (Hi Clone).

Imaging

Calcium transients in ATP-responsive cells and loading of taste cells with polar tracers were visualized with an ICCD camera IC-200 (Photon Technology International) and a digital camera Axiocam (Zeiss), respectively, using an Axioscope-2 microscope and a water-immersion objective Achroplan × 40, NA=0.8 (Zeiss). For Ca2+ imaging, dispersed COS-1 cells were loaded with 2 μM Fluo-4AM for 35 min in the presence of Pluronic (0.002%) at room temperature. Dye-loaded cells were transferred to a recording chamber and their fluorescence was excited with a light-emitting diode (Luxion) at 480 nm. Cell emission was filtered at 535±25 nm and sequential fluorescence images were acquired every 0.5–2 s with Workbench 5.2 software (INDEC Biosystems). To assay the responsiveness of individual cells, cells were stimulated by bath application of ATP as well as neuroactive or bitter compounds.

Linear antisense RNA amplification and PCR analysis

First-strand cDNA was synthesized directly from cell lysates using oligo(dT)15-T7 primer and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Second-strand cDNA was synthesized with RNase H (Invitrogen) and DNA polymerase I (Promega). The antisense RNA (aRNA) amplification by in vitro transcription was carried out using T7 RNA polymerase (Promega). The DNA template was removed by incubating the reaction mixture with DNaseI (Sigma). Amplified aRNA was purified using the RNeasy MinElute kit (Qiagen) and was reverse-transcribed with SuperScript III (Invitrogen) and random pimers. The experiment was performed in triplicate. Protocols are detailed in Supplementary data IV.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections from mouse CV papillae were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution: 1:500 for rabbit anti-TRPM5; 1:500 for chicken anti-Panx1 (Diatheva); 1:500 for rabbit anti-PLCβ2 (Santa Cruz). For double immunostaining, sections were incubated with anti-Panx1 along with either anti-TRPM5 or anti-PLCβ2. Secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution: 1:500 for alexa fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes); 1:500 for fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgY antibody (Aves). Images were obtained by confocal microscopy. Protocols are detailed in Supplementary data V.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Howard Hughes Medical Institute (grant 55000319 to SSK), Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grants 04-04-97208 and 05-04-48203 to SSK), and National Institutes of Health (grant DC03055 to RFM and grant DC07984 to PJ).

References

- Abraham EH, Prat AG, Gerweck L, Seneveratne T, Arceci RJ, Kramer R, Guidotti G, Cantiello HF (1993) The multidrug resistance (mdr1) gene product functions as an ATP channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 312–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenet P, Lindemann B (1991) Noninvasive recording of receptor cell action potentials and sustained currents from single taste buds maintained in the tongue: the response to mucosal NaCl and amiloride. J Membr Biol 124: 33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L, Locovei S, Dahl G (2004) Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP. FEBS Lett 572: 65–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DL, Sullivan SL, Lavoie EG, Sevigny J, Finger TE (2006) Nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-2 is the Ecto-ATPase of type I cells in taste buds. J Comp Neurol 497: 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baryshnikov SG, Rogachevskaja OA, Kolesnikov SS (2003) Calcium signaling mediated by P2Y receptors in mouse taste cells. J Neurophysiol 90: 3283–3294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell PD, Lapointe J-Y, Sabirov R, Hayashi S, Peti-Peterdi J, Manabe K, Kovacs G, Okada Y (2003) Macula densa cell signaling involves ATP release through a maxi anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 4322–4327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MV, Contreras JE, Bukauskas FF, Saez JC (2003) New roles for astrocytes: gap junction hemichannels have something to communicate. Trends Neurosci 26: 610–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo X, Alavi A, Xiang Z, Oglesby I, Ford A, Burnstock G (1999) Localization of ATP-gated P2X2 and P2X3 receptor immunoreactive nerves in rat taste buds. Neuroreport 10: 1107–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodin P, Burnstock G (2001) Purinergic signalling: ATP Release. Neurochem Res 26: 959–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braet K, Aspeslagh S, Vandamme W, Willecke K, Martin PE, Evans WH, Leybaert L (2003) Pharmacological sensitivity of ATP release triggered by photoliberation of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate and zero extracellular calcium in brain endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol 197: 205–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, Barbe MT, Jakob NJ, Monyer H (2005) Pharmacological properties of homomeric and heteromeric pannexin hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurochem 92: 1033–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G (2001) Purine-mediated signalling in pain and visceral perception. Trends Pharm Sci 22: 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystrova MF, Yatzenko YE, Fedorov IV, Rogachevskaja OA, Kolesnikov SS (2006) P2Y isoforms operative in mouse taste cells. Cell Tissue Res 323: 377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaytor AT, Evans WH, Griffith TM (1997) Peptides homologous to extracellular loop motifs of connexin 43 reversibly abolish rhythmic contractile activity in rabbit arteries. J Physiol 503: 99–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaytor AT, Martin PEM, Edwards DH, Griffith TM (2001) Gap junctional communication underpins EDHF-type relaxations evoked by ACh in the rat hepatic artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2441–H2450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp TR, Medler KF, Damak S, Margolskee RF, Kinnamon SC (2006) Mouse taste cells with G protein-coupled taste receptors lack voltage-gated calcium channels and SNAP-25. BMC Biol 4: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp TR, Yang R, Stoick CL, Kinnamon SC, Kinnamon JC (2004) Morphologic characterization of rat taste receptor cells that express components of the phospholipase C signaling pathway. J Comp Neurol 468: 311–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotrina ML, Lin JH, Alves-Rodrigues A, Liu S, Li J, Azmi-Ghadimi H, Kang J, Naus CC, Nedergaard M (1998) Connexins regulate calcium signaling by controlling ATP release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 15735–15740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruciani V, Mikalsen S-O (2006) The vertebrate connexin family. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 1125–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings TA, Powell J, Kinnamon SC (1993) Sweet taste transduction in hamster taste cells: evidence for the role of cyclic nucleotides. J Neurophysiol 70: 2326–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fazio RA, Dvoryanchikov G, Maruyama Y, Kim JW, Pereira E, Roper SD, Chaudhari N (2006) Separate populations of receptor cells and presynaptic cells in mouse taste buds. J Neurosci 26: 3971–3980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vuyst E, Decrock E, Cabooter L, Dubyak GR, Naus CC, Evans WH, Leybaert L (2006) Intracellular calcium changes trigger connexin 32 hemichannel opening. EMBO J 25: 34–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandari S, Zampighi GA, Leung DW, Wright EM, Loo DDE (2002) Inhibition of gap junction hemichannels by chloride channel blockers. J Membr Biol 185: 93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger TE, Danilova V, Barrows J, Bartel DL, Vigers AJ, Stone L, Hellekant G, Kinnamon SC (2005) ATP signaling is crucial for communication from taste buds to gustatory nerves. Science 310: 1495–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossier P, Tauc L, Baux G (1999) Calcium transients and neurotransmitter release at an identified synapse. Trends Neurosci 22: 161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough DA, Paul DL (2003) Beyond the gap: functions of unpaired connexon channels. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazama A, Fan HT, Abdullaev I, Maeno E, Tanaka S, Ando-Akatsuka Y, Okada Y (2000) Swelling-activated, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-augmented ATP release and Cl− conductances in murine C127 cells. J Physiol 523: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herness MS, Gilbertson TA (1999) Cellular mechanisms of taste transduction. Annu Rev Physiol 61: 873–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-J, Maruyama Y, Lu K-S, Pereira E, Plonsky I, Baur JE, Wu D, Roper SD (2005) Mouse taste buds use serotonin as a neurotransmitter. J Neurosci 25: 843–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume JR, Duan D, Collier ML, Yamazaki J, Horowitz B (2000) Anion transport in heart. Physiol Rev 80: 31–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka S, Toyono T, Seta Y, Ogura T, Toyoshima K (2004) Expression of P2Y1 receptors in rat taste buds. Histochem Cell Biol 121: 419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-Y, Cho S-W, Lee M-J, Hwang H-J, Lee J-M, Lee S-I, Muramatsu T, Shimono M, Jung H-S (2005) Inhibition of connexin 43 alters Shh and Bmp-2 expression patterns in embryonic mouse tongue. Cell Tissue Res 320: 409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YV, Bobkov YV, Kolesnikov SS (2000) ATP mobilizes cytosolic calcium and modulates ionic currents in mouse taste receptor cells. Neurosci Lett 290: 165–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC, Harden TK (2003) Mechanisms of release of nucleotides and integration of their action as P2X- and P2Y-receptor activating molecules. Mol Pharmacol 64: 785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leybaert L, Braet K, Vandamme W, Cabooter L, Martin PEM, Evans WH (2003) Connexin channels, connexin mimetic peptides and ATP release. Cell Comm Adhes 10: 251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Liman ER (2003) Intracellular Ca2+ and the phospholipid PIP2 regulate the taste transduction ion channel TRPM5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15160–15165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locovei S, Bao L, Dahl G (2006) Pannexin 1 in erythrocytes: function without a gap. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7655–7659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medler KF, Margolslee RF, Kinnamon SC (2003) Electrophysiological characterization of voltage-gated currents in defined taste cell types in mice. J Neurosci 23: 2608–2617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignen O, Egee S, Liberge M, Harvey BJ (2000) Basolateral outward rectifier chloride channel in isolated crypts of mouse colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: 277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto T, Popov S, Buckley KM, Poo MM (1995) Calcium-dependent transmitter secretion from fibroblasts: modulation by synaptotagmin I. Neuron 15: 689–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchin Y, Kelmanson I, Matz M, Lukyanov K, Usman N, Lukyanov S (2000) A ubiquitous family of putative gap junction molecules. Curr Biol 10: R473–R474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prawitt D, Monteilh-Zoller MK, Brixel L, Spangenberg C, Zabel B, Fleig A, Penner R (2003) TRPM5 is a transient Ca2+-activated cation channel responding to rapid changes in [Ca2+]i. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15166–15171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Kolesnikov SS (2006) Electrophysiologically identified subpopulations of taste bud cells. Neurosci Lett 395: 249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper SD (2006) Cell communication in taste buds. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 1494–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabirov RZ, Dutta AK, Okada Y (2001) Volume-dependent ATP-conductive large-conductance anion channel as a pathway for swelling-induced ATP release. J Gen Physiol 118: 251–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savchenko A, Barnes S, Kramer RH (1997) Cyclic-nucleotide-gated channels mediate synaptic feedback by nitric oxide. Nature 390: 694–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K (2004) The sweet and the bitter of mammalian taste. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14: 423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas M, Hopperstad MG, Spray DC (2001) Quinine blocks specific gap junction channel subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10942–10947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling P, Matthews G (2005) Structure and function of ribbon synapses. Trends Neurosci 28: 20–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout CE, Costantin JL, Naus CC, Charles AC (2002) Intercellular calcium signaling in astrocytes via ATP release through connexin hemichannels. J Biol Chem 277: 10482–10488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suadicani SO, Brosnan CF, Scemes E (2006) P2X7 receptors mediate ATP release and amplification of astrocytic intercellular Ca2+ signaling. J Neurosci 26: 1378–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M, Okada T (1991) Release of endogenous excitatory amino acids from ON-type bipolar cells isolated from the goldfish retina. J Neurosci 11: 2199–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera K, Yasumatsu K, Voets T, Droogmans G, Shigemura N, Ninomiya Y, Margolskee RF, Nilius B (2005) Heat activation of TRPM5 underlies thermal sensitivity of sweet taste. Nature 438: 1022–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Van Nhieu G, Clair C, Bruzzone R, Mesnil M, Sansonetti P, Combettes L (2003) Connexin-dependent inter-cellular communication increases invasion and dissemination of Shigella in epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol 5: 720–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich ND, Voetsa T, Prenena J, Vennekensa R, Talaveraa K, Droogmansa G, Nilius B (2005) Comparison of functional properties of the Ca2+-activated cation channels TRPM4 and TRPM5 from mice. Cell Calcium 37: 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelder RN, von Zastrow ME, Yool A, Dement WC, Barchas JD, Eberwine JH (1990) Amplified RNA synthesized from limited quantities of heterogeneous cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 1663–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner A, Clements DK, Parikh S, Evans WH, DeHaan RL (1995) Specific motifs in the external loops of connexin proteins can determine gap junction formation between chick heart myocytes. J Physiol 488: 721–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GT, Ruiz-Avila L, Margolskee RF (1999) Directing gene expression to gustducin-positive taste receptor cells. J Neurosci 19: 5802–5809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information