Abstract

Vibrio cholerae undergoes phenotypic variation that generates two morphologically different variants, termed smooth and rugose. The transcriptional profiles of the two variants differ greatly, and many of the differentially regulated genes are controlled by a complex regulatory circuitry that includes the transcriptional regulators VpsR, VpsT, and HapR. In this study, we identified the VpsT regulon and compared the VpsT and VpsR regulons to elucidate the contribution of each positive regulator to the rugose variant transcriptional profile and associated phenotypes. We have found that although the VpsT and VpsR regulons are very similar, the magnitude of the gene regulation accomplished by each regulator is different. We also determined that cdgA, which encodes a GGDEF domain protein, is partially responsible for the altered vps gene expression between the vpsT and vpsR mutants. Analysis of epistatic relationships among hapR, vpsT, and vpsR with respect to a whole-genome expression profile, colony morphology, and biofilm formation revealed that vpsR is epistatic to hapR and vpsT. Expression of virulence genes was increased in a vpsR hapR double mutant relative to a hapR mutant, suggesting that VpsR negatively regulates virulence gene expression in the hapR mutant. These results show that a complex regulatory interplay among VpsT, VpsR, HapR, and GGDEF/EAL family proteins controls transcription of the genes required for Vibrio polysaccharide and virulence factor production in V. cholerae.

Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of the disease cholera, is a facultative human pathogen with aquatic and intestinal life cycles (14). Thus, the pathogen must be able to sense and respond to its environment and is likely to have multiple environmental adaptation strategies. One environmental adaptation strategy used by microorganisms and common in bacteria that occupy multiple ecosystems (22) is phenotypic variation, which is defined as a population heterogeneity that can arise from genetic rearrangements or variable expression patterns in an isogenic population (48). Phenotypic variation is thought to increase the adaptation capabilities of the organism to fluctuating environmental parameters. V. cholerae has the capacity to undergo a phenotypic variation event which results in the generation of two morphologically different variants, termed smooth and rugose (57). Although both variants are pathogenic and retain their colonial morphologies after a passage through the human host (43), they differ greatly in their capacities to resist environmental stresses. It has been shown by Rice et al. and Morris et al. that conversion to the rugose variant is associated with increased survival in chlorinated water (43, 44). The rugose variant also exhibits increased resistance to osmotic and oxidative stress compared to the smooth variant (43, 56, 60). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that the smooth-to-rugose switch is a defensive strategy used by V. cholerae against predation by protozoan grazing (38).

Another environmental adaptation strategy used by microorganisms is to form biofilms, which are surface-attached microbial communities composed of microorganisms and their extrapolymeric substances. V. cholerae forms biofilms by attaching to abiotic surfaces, surfaces of phytoplankton, and zooplankton (24, 27, 28, 52). Laboratory microcosm studies have shown that during coculture, V. cholerae effectively attaches to surfaces of zooplankton and phytoplankton, and this association increases the survival of the organism compared to V. cholerae cultured without added plankton (25, 26); thus, it has been proposed that biofilm formation is crucial to the survival of this organism in aquatic habitats between epidemics. Furthermore, it was proposed that during its infection cycle, V. cholerae enters into the host in biofilms which provide protection from the acid stress that the pathogen encounters during the passage of the stomach (62). It has been recently shown that V. cholerae is disseminated from the infected host in both planktonic and biofilm states (15).

Recent studies have documented that smooth-to-rugose phenotypic variation and capacities to form biofilms are linked phenotypes. The rugose variant shows a preference for a biofilm lifestyle as it has an increased capacity to produce an exopolysaccharide, termed VPS for Vibrio polysaccharide, which is required for development of mature biofilms of V. cholerae (60). VPS is also responsible for the resistance of the rugose variant to osmotic, acid, and oxidative stress (56, 60). Even though both rugose and smooth variants are capable of forming biofilms, biofilm development dynamics as well as characteristics of the mature biofilm structures formed by rugose and smooth variants differ greatly where the biofilm-forming capacity of the rugose variant is superior to that of smooth variant (60).

The structural and regulatory genes involved in the development of the rugose colonial morphology and, in turn, in biofilm formation have been extensively studied (6, 58-60). The vps genes, which are organized into two clusters (vpsA-K and vpsL-Q) on the large chromosome, are required for VPS production and rugose colony formation (60). Expression of the vps genes is positively regulated by the transcriptional regulators VpsR and VpsT, both exhibiting homology to response regulators of the two-component regulatory system (6, 58). Disruption of either vpsR or vpsT in the rugose genetic background yields smooth colonial morphology and decreases expression of the vps genes, VPS production, and biofilm formation (6, 58). Expression of the vps genes, VPS production, and rugose colony formation are also under negative regulation. In the strain used in this study, V. cholerae O1 El Tor (A1552), mutations in the quorum-sensing regulator HapR in the rugose genetic background led to production of superrugose colonies (59).

To characterize changes in gene expression that accompany smooth-to-rugose phenotypic variation, we previously compared whole-genome gene expression profiles of these variants during exponential growth phase in liquid Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and determined that 3.2% of the genes in the V. cholerae genome are differentially regulated in the smooth compared to the rugose variant (59). Furthermore, we showed that expression of a large set of these genes is positively regulated by VpsR and negatively regulated by HapR (59).

Even though disruption of either vpsR or vpsT in the rugose genetic background reduces vps gene expression and yields phenotypically smooth colonies (6, 58), at present it is not known whether VpsT and VpsR regulate similar genes and processes in the rugose variant and whether they act in the same or parallel pathways. Similarly, the relationship between the positive regulators VpsT and VpsR with the negative regulator HapR has not been investigated. To better understand the contribution of these regulators to the phenotypic variation, we generated vpsT, vpsR, vpsT vpsR, hapR, vpsT hapR, vpsR hapR, and vpsT vpsR hapR mutants and characterized the mutants with respect to their gene expression profile, colony morphology, and biofilm formation. Our analysis revealed the existence of a complex regulatory interplay among VpsT, VpsR, HapR, and GGDEF (diguanylate cyclases) and EAL (phosphodiesterases) domain proteins, which control the levels of the second messenger bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) in controlling the expression of the genes required for rugosity and virulence factor production in V. cholerae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used for standard DNA manipulation experiments, and the E. coli strain S17-1 λpir was used for conjugation with V. cholerae. Bacteria were grown in LB broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl) with aeration at 30°C unless otherwise noted. Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations unless otherwise noted: rifampin and ampicillin at 100 μg/ml and gentamicin at 50 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype and phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | λ− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | Promega |

| S17-1λpir | recAthi pro rK− mK+RP4::2-Tc::MuKm Tn7 Tpr Smr λpir | 11 |

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| Fy_Vc_1 | V. cholerae O1 El Tor A1552; smooth variant; Rifr | 60 |

| Fy_Vc_2 | V. cholerae O1 El Tor A1552; rugose variant; Rifr | 60 |

| Fy_Vc_237 | Fy_Vc_1 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr | 3 |

| Fy_Vc_240 | Fy_Vc_2 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr | 35 |

| Fy_Vc_5 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔvpsT ΔlacZ; Rifr | 6 |

| Fy_Vc_1956 | Fy_Vc_5 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_6 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔvpsR ΔlacZ; Rifr | 6 |

| Fy_Vc_1955 | Fy_Vc_6 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_2037 | Fy_Vc_2 vpsR::pGP704; Rifr Apr | 57 |

| Fy_Vc_7 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔvpsR ΔvpsT ΔlacZ; Rifr | 6 |

| Fy_Vc_1957 | Fy_Vc_7 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_2038 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔvpsT ΔlacZvpsR::pGP704; Rifr Apr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1951 | Fy_Vc_2 hapR::pGP704; Rifr Apr | 59 |

| Fy_Vc_1958 | Fy_Vc_1951 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr Apr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1952 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔvpsT ΔlacZhapR::pGP704; Rifr Apr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1959 | Fy_Vc_1952 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr Apr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1953 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔvpsR ΔlacZhapR::pGP704; Rifr Apr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1960 | Fy_Vc_1953 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr Apr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1954 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔvpsR ΔvpsT ΔlacZhapR::pGP704; Rifr Apr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1961 | Fy_Vc_1954 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr Apr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_343 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔcdgA; Rifr | 35 |

| Fy_Vc_359 | Fy_Vc_343 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr | 35 |

| Fy_Vc_1717 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔcdgA ΔvpsT; Rifr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1733 | Fy_Vc_1733 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1721 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔcdgA ΔvpsR; Rifr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1458 | Fy_Vc_1458 mTn7-GFP; Rifr Gmr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1731 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔcdgA ΔhapR; Rifr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1725 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔcdgA ΔvpsT ΔhapR; Rifr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_1446 | Fy_Vc_2 ΔcdgA ΔvpsR ΔhapR; Rifr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_183 | Fy_Vc_1 ΔhapR; Rifr | This study |

| Fy_Vc_344 | Fy_Vc_1 ΔcdgA; Rifr | 35 |

| Fy_Vc_1675 | Fy_Vc_1 ΔcdgA ΔhapR; Rifr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGP704-sac28 | pGP704 derivative; sacB; Apr | G. Schoolnik |

| pGP704 | Suicide plasmid; Apr | 41 |

| pGP704::vpsR | 57 | |

| pGP704::hapR | 58 | |

| pCC2 | pGP704-sac28::ΔlacZ; Apr | 6 |

| pCC9 | pGP704-sac28::ΔvpsT; Apr | 6 |

| pCC27 | pGP704-sac28::ΔvpsR; Apr | 6 |

| pFY-9 | pGP704-sac28::ΔhapR; Apr | G. Schoolnik |

| pFY-149 | pGP704-sac28::ΔcdgA; Apr | 35 |

| pMCM11 | pGP704::mTn7-GFP; Gmr Apr | M. Miller and G. Schoolnik |

| pUX-BF13 | oriR6K helper plasmid, provides Tn7 transposition function in trans; Apr | 2 |

Construction of the mutants.

V. cholerae deletion mutants were constructed as previously described (16, 35), and insertion mutants were constructed as described previously (60). The RΔvpsT vpsR::pGP704 double mutant, which was used only for gene expression profiling experiments, was generated by biparental mating between the E. coli S17-1 λpir strain harboring pGP704::vpsR and RΔvpsT (the prefixes R and S are used to indicate rugose and smooth genetic backgrounds). The RΔvpsR hapR::pGP704 and RΔvpsT hapR::pGP704 double mutants were generated by biparental mating between the E. coli S17-1 λpir strain harboring pGP704::hapR and RΔvpsR and RΔvpsT, respectively. The RΔvpsT ΔvpsR hapR::pGP704 triple mutant was generated via biparental mating between the RΔvpsT ΔvpsR mutant and the E. coli S17-1 λpir strain harboring pGP704::hapR. Following mating, the exconjugants were selected on LB plates supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and rifampin. Insertion into the correct site was confirmed by PCR analysis.

RNA isolation.

Cultures of V. cholerae grown overnight in LB medium at 30°C were diluted 1:200 in fresh LB medium incubated at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) until they reached mid-exponential phase. To ensure homogeneity, exponential-phase cultures were diluted 1:100 in fresh LB medium and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 to 0.4. Two-milliliter aliquots were collected by centrifugation for 2 min at room temperature. The cell pellets were immediately resuspended in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and stored at −80°C. The total RNA from the pellets and colonies was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). To remove contaminating DNA, total RNA was incubated with RNase-free DNase I (Ambion), and an RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN) was used to clean up RNA after DNase digestion.

Gene expression profiling.

Microarrays used in this study were composed of 70-mer oligonucleotides (designed and synthesized by Illumina, San Diego) representing most of the open reading frames present in the V. cholerae genome and were printed using a robotic arrayer located on the University of California-Santa Cruz campus. Whole-genome expression analysis was performed using a common reference RNA which was either a mixture of equal amounts of total RNA isolated from smooth and rugose variants grown to exponential and stationary phases or a mixture of equal amounts of total RNA isolated from smooth and rugose variants grown to exponential phase. Equal amounts of RNA from the test samples and reference sample were used in reverse transcription and hybridization reactions as described previously (3). After hybridization, slides were washed once in a wash buffer containing 1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate and three times in 0.06× SSC. Slides were dried by spinning at 700 rpm for 5 min at 25°C and then scanned by an Axon scanner to determine the fluorescence of each dye in each open reading frame-specific spot. The raw data were obtained by using GenePix 4.1. Normalized signal ratios were obtained with LOWESS print-tip normalization by using Bioconductor packages (http://www.bioconductor.org) in the R environment. Differentially regulated genes were determined (using two biological and two technical replicates for each data point) with Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) software (54) by using a 1.5-fold difference in gene expression and 3% false discovery rate as cutoff values. These data were also analyzed by different clustering methods to identify genes with similar expression patterns using GENESIS software (51).

qRT-PCR.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed for a selected set of genes to validate the gene expression data obtained from microarray experiments. To this end, RNA samples were isolated from exponentially grown (OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4) mutant and wild-type strains as described above. Total RNA has been used in a reverse transcription reaction. Two micrograms of RNA and 5 μg of random hexamers were denatured at 80°C for 5 min and then chilled on ice for 5 min. The reaction mixture containing first-strand buffer (Invitrogen), 0.01 M dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, and 100 U of SuperScript III (Invitrogen) was added to the cooled samples and incubated at 42°C for 3 h and then at 50°C for 10 min. Each 30-μl reaction mixture was diluted with nuclease-free water sixfold. The real-time PCR mixture included 6 μl of diluted cDNA, 10 μl of 2× SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), and a 500 nM concentration of each primer. Reactions were carried out in an MJ Research Opticon 2 thermocycler by using the following cycle parameters: 95°C for 2 min and 30 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 57°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 20 s, followed by a melting curve analysis from 55°C to 90°C. Standard curves were prepared from chromosomal DNA of V. cholerae O1 El Tor smooth variant (1, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 ng) to correlate the amount of DNA to cycle thresholds. An R2 value of at least 0.995 was obtained for all the primer pairs that were used in this study (see Table S10 in the supplemental material). The cycle thresholds were determined for samples, and they were converted to an equivalent amount of DNA by using standard curves. The gyrA gene encoding DNA gyrase subunit A was used to normalize expression values.

Colony morphology.

Colonies formed on LB agar plates after 2 days of incubation at 30°C were photographed using a Nikon Coolpix 4500 digital camera.

GFP tagging of V. cholerae strains.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged strains are provided in Table 1. The insertion of the GFP gene into the V. cholerae genome was performed via triparental mating among V. cholerae, E. coli S17-1 λpir carrying pUX-BF13, and E. coli S17-1 λpir carrying pMCM11. Exconjugants were selected on TCBS (thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose) agar plates with gentamicin (50 μg/ml). The mini-Tn7 cassette inserts at a specific site in the V. cholerae genome, between VC0487 and VC0488 (nucleotides 519257 to 519261), causing a 5-bp duplication. Confirmation of the GFP insertion was done by colony PCR using the primers GFP_1 (ATCCCAATGCAACTGCTCTC) and GFP_2 (ACTCGGATCTCGACACAAGC). The growth rate of each GFP-tagged strain was compared to its corresponding parental background to ensure that the GFP insertion would not interfere with growth.

Biofilm assays.

For flow cell experiments, biofilms were grown at room temperature in flow chambers (individual channel dimensions of 1 by 4 by 40 mm) supplied with 2% LB at a flow rate of 10.2 ml h−1. The flow cell system was assembled and prepared as described previously (23). Cultures for inoculation of the flow chambers were prepared by inoculating 6 to 10 single colonies from a plate into flasks containing LB medium and growing them with aeration at 30°C for 20 h. Cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 in 2% LB and used for inoculation. Inoculation of the samples was performed as described previously (59).

For non-flow cell experiments, cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 in LB medium, and 3 ml of diluted culture was placed into a chambered coverglass system (Lab-Tek). Chambers were incubated at 30°C for 8 h and, prior to image acquisition, washed twice with 1 ml of LB. Image acquisition was done with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M laser scanning microscope. IMARIS personal software (Bitplane) and Adobe Photoshop were used for further image processing.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of the VpsT regulon.

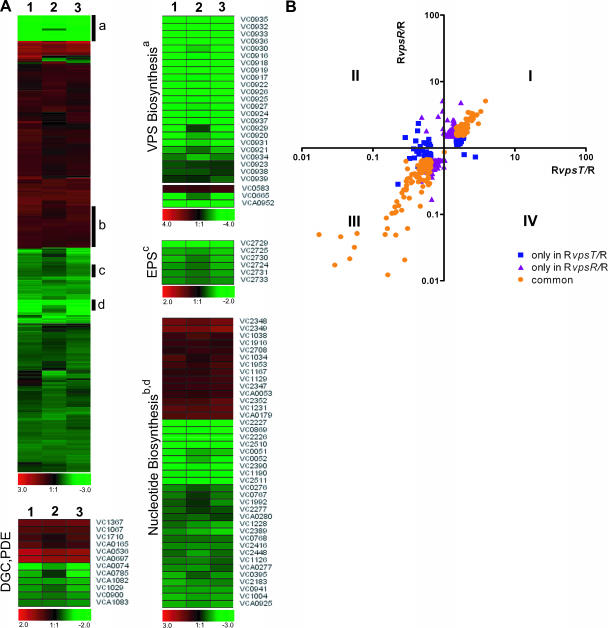

Disruption of vpsT in the rugose genetic background (denoted RvpsT) reduces vps gene expression, yields phenotypically smooth colonies, and reduces biofilm-forming capacity (6). To identify genes whose regulation is VpsT dependent in the rugose genetic background, we compared transcriptional profiles of the RvpsT mutant with transcriptional profiles of the wild-type rugose variant during exponential-phase growth. The gene expression data were analyzed by SAM software (54) using the following criteria to define significantly regulated genes: ≤3% false-positive discovery rate and ≥1.5-fold transcript abundance differences between the samples. These criteria led to the identification of 288 (7.4% of the whole genome) genes that are differentially expressed between the RvpsT mutant and the rugose variant. The expression of 189 genes (66%) was lower in the RvpsT mutant than in the rugose variant, indicating that these genes require VpsT for their expression. In contrast, the expression of 99 genes (34%) was higher in the RvpsT mutant than in the rugose variant, indicating that their expression is normally repressed through the action of VpsT. Based on annotated functions provided by the V. cholerae genome sequencing project, the genes regulated by VpsT are predicted to participate in a variety of cellular functions. For the complete list of differentially regulated genes, see Table S1 in the supplemental material. Below, we discuss expression patterns of selected subsets of these genes that are required for exopolysaccharide production and/or secretion as well as genes controlling nucleotide pools in the cell, which may influence intracellular levels of c-di-GMP by altering cellular GTP levels.

Expression of many of the vps genes (VC0916, VC0917 to VC0927, and VC0934 to VC0939) which encode VPS biosynthetic enzymes, many of the vps intergenic region genes, and vpsR (encoding the positive transcriptional regulator VpsR) was markedly reduced in the RvpsT mutant (Fig. 1A), thus corroborating prior gene expression studies (6). We further confirmed this finding by qRT-PCR analysis as shown in Table 2. In contrast, expression of VC0583, encoding HapR, was increased 1.7-fold in the RvpsT mutant; similarly, expression of hapR was increased 1.9-fold in the RvpsR mutant during exponential phase. Taken together, these results indicate that both VpsT and VpsR negatively regulate (directly or indirectly) transcription of hapR during exponential growth. This finding was further confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis, which indicated that hapR expression was increased in the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants and in the RvpsT vpsR double mutant 1.5- to 1.9-fold relative to the rugose wild type (Table 2). HapR, a central transcriptional regulator of the quorum-sensing circuit in V. cholerae, negatively regulates virulence, rugosity, and biofilm development phenotypes (18, 40, 59, 62, 63). Expression of hapR is under complex regulation. hapR expression is repressed by the action of LuxO in a cell density-dependent manner (18, 55). At low cell density, LuxO is activated via phosphorylation and prevents hapR transcription by increasing the transcription of a set of small RNAs (18, 34). In contrast, at high cell density, due to accumulation of autoinducers, LuxO is dephosphorylated, and expression of hapR is increased. It has also been shown that the VarA/VarS two-component regulatory system is part of the quorum-sensing regulatory circuit and controls hapR transcription (33). Recent studies have identified a transcriptional regulator, VqmA, which positively regulates hapR transcription at low cell densities (36). Our experiments were performed in exponentially grown cells where hapR message levels are predicted to be low due to the regulatory mechanisms discussed above. Both expression profiling and qRT-PCR results suggest that VpsT and VpsR also contribute to modulation of message abundance of hapR. At present, we do not know whether VpsT and VpsR modulate hapR transcription through LuxO or VqmA or by another pathway yet to be identified. This finding indicates that VpsT and VpsR, besides being positive transcriptional activators of vps genes, can also contribute to transcription of vps genes by causing a reduction in hapR message levels, as HapR negatively regulates vps transcription in a direct or indirect manner (59, 62).

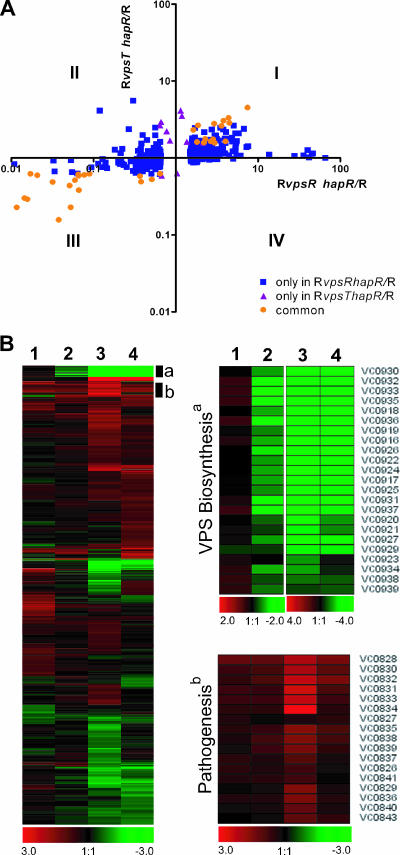

FIG. 1.

Expression profiles of RvpsT, RvpsR, and RvpsT vpsR mutants. (A) Differentially expressed genes in RvpsR (lane 1), RvpsT (lane 2), and RvpsT vpsR (lane 3) mutants are clustered by using Euclidian distance and average linkage hierarchical clustering. A compact view of clustered genes is presented using the log2-based color scale shown at the bottom of the panels (red, induced; green, repressed). Clusters that contain the genes required for VPS biosynthesis, the EPS general secretion system, and nucleotide biosynthesis are marked with black bars and labeled with a, c, and b and d, respectively. The expression profiles of these genes and genes encoding diguanylate cyclases (DGC) and/or phosphodiesterases (PDE) are also shown as separate heat maps. (B) Comparison of gene expression profiles of the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants. The x and y axes indicate the relative changes in gene expression (n-fold) in the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants relative to the wild-type rugose strain, respectively, whereby each spot represents a gene that was differentially regulated by 1.5-fold in at least one experiment. The plot area is divided into four regions (I to IV) based on the expression patterns relative to the wild-type rugose strain. Blue squares indicate genes differentially expressed only in the RvpsT mutant, purple triangles indicate genes differentially expressed only in the RvpsR mutant, and orange circles indicate genes differentially expressed in both mutants.

TABLE 2.

qRT-PCR analysis of vps and tcpA gene regulation in vps regulatory mutants

| Strain or variant | Gene induction ratioa

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vpsA | vpsL | vpsR | vpsT | tcpA | hapR | |

| Smooth | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 1.76 ± 0.27 | |

| RvpsT | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.08 | ND | 1.59 ± 0.33 | |

| RvpsR | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | ND | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 1.54 ± 0.24 | |

| RvpsT vpsR | 0 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | ND | ND | 1.91 ± 0.29 | |

| RhapR | 1.42 ± 0.32 | 2.14 ± 0.50 | 1.34 ± 0.19 | 1.41 ± 0.17 | 1.48 ± 0.21 | 1.79 ± 0.28b |

| RvpsT hapR | 1.22 ± 0.26 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 1.15 ± 0.28 | ND | 0.89 ± 0.12 | 1.91 ± 0.30b |

| RvpsR hapR | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0 | ND | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 1.97 ± 0.22 | 1.95 ± 0.58b |

| RvpsT vpsR hapR | 0 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | ND | ND | 2.65 ± 0.45b | |

| ScdgA | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | ||||

| RcdgA | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.08 | ||||

Gene induction ratios are calculated relative to the rugose wild-type strain. Data are normalized by using gyrA as a control. Numbers given are average ± standard deviation of a representative three replicates. ND, not detected.

Mutants were generated by insertion and the oligonucleotides used for qRT-PCR analysis located preceding the insertion site.

Expression of 2 of the 15 eps (extracellular protein secretion) genes, located in a 12-gene operon containing epsC-epsN, was decreased ≥1.5-fold in the RvpsT mutant (Fig. 1A). The EPS type II secretion system is required for the secretion of proteins through the outer membrane including cholera toxin, hemagglutinin/protease, chitinase, neuraminidase, and lipase and may also be required for either VPS secretion or for the secretion of protein(s) involved in the transport/assembly of VPS (1). We have previously shown that expression of eps genes is higher in the rugose variant than in the smooth variant, and here we show that transcription of eps genes is regulated directly by VpsT.

Expression of many of the genes required for de novo purine and pyrimide biosynthesis was reduced in the RvpsT mutant relative to the wild type (Fig. 1A). These genes include the following: VC0051 (purK, phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase; ATPase subunit), VC0052 (purE, phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase; catalytic subunit), VC0768 (guaA, GMP synthase), VC0869 (purL, phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase), VC1004 (purF, amidophosphoribosyltransferase), VC1126 (purB, adenylosuccinate lyase), VC1228 (purT, phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase II), VC2183 (prsA, ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase), VC2226 (purM, phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine cyclo-ligase), VC2227(purN, phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase), VC2389 (carB, carbamoyl-phosphate synthase; large subunit), VC2390 (carA, carbamoyl-phosphate synthase; small subunit), VC2448 (pyrG, CTP synthase), VC2510 (pyrB, aspartate carbamoyltransferase; catalytic subunit), VC2511 (pyrI, aspartate carbamoyltransferase; regulatory subunit), and VCA0925 (pyrC, dihydroorotase). Pools of purine bases and nucleotides are critical for regulation of expression of the genes required for de novo and salvage pathways. The purine repressor (PurR), which uses hypoxanthine and guanine as corepressors, regulates expression of the genes required for AMP and GMP biosynthesis in response to purine availability (39). In E. coli, PurR and additional genes connected with nucleotide metabolism such as pyrC, pyrD, codBA, prsA, glyA, the gvc operon, and speA are also regulated by PurR (9, 20, 50). Interestingly, in the RvpsT mutant, expression levels of VC0941 (glyA-1), encoding a serine hydroxyl methyl transferase (involved in glycine synthesis), and VCA0277 and VCA0280, encoding components of the glycine cleavage system proteins gvcH and gvcT, respectively, were reduced. In E. coli, the glyA gene product is responsible for production of glycine, and the gvc system is involved in catabolism of glycine to CO2, NH3, and a one-carbon methylene group which is used in biosynthesis of purines, thymine, and methionine (61). Intriguingly, in E. coli, CsgD, which is a regulator of curli and cellulose synthesis and a homolog of VpsT, positively regulates expression of the glyA gene (7). In E. coli, glyA expression is directly activated by MetR and its coactivator homocysteine, while PurR and corepressors guanine or hypoxanthine directly repress glyA expression (37, 49, 50). It had been speculated that CsgD may alter glyA expression either by influencing the transcription of purR and metR or by binding to coactivators or repressors (8). We did not see any changes in expression of metR and purR, suggesting that VpsT mediates increases in glyA expression directly or indirectly via another regulatory protein or through PurR but in a posttranscriptional manner.

In contrast, transcription of some genes involved in purine nucleotide and nucleoside interconversion—VC1038 (udk, uridine kinase), VC1129 (gsk-1, inosine-guanosine kinase), and VC2708 (gmk, guanylate kinase)—and transcription of genes whose products are involved in the catabolism of nucleotides for use as an energy and carbon source as well as in synthesis of nucleotides—VC1231 (cdd, cytidine deaminase), VC2347 (deoD-1, purine nucleoside phosphorylase), VC2348 (deoB, phosphopentomutase), and VC2349 (deoA, thymidine phosphorylase)—were higher in the RvpsT mutant than in the wild type (Fig. 1A). Similarly, expression of three genes encoding NupC family proteins (VC1953, VC2352, and VCA0179) that are predicted to be involved in nucleoside transport was higher in the RvpsT mutant. These results all together suggest that VpsT directly or indirectly regulates expression of the genes required for de novo purine and pyrimide biosynthesis, the nucleoside catabolism and uptake functions, and thereby controls nucleotide pools in the cell.

Expression of a set of genes encoding proteins harboring GGDEF and EAL domains was altered in the RvpsT mutant. Expression of cdgD (VCA0697), cdgE (VC1367), VCA0536, and VC1067 was increased while expression of cdgA (VCA0074) and VCA1082 was decreased in RvpsT compared to the wild type (Fig. 1A). Proteins with GGDEF and EAL domains function as diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases, respectively, and modulate cellular c-di-GMP levels (10, 45, 46). c-di-GMP is a second messenger that modulates the cell surface properties of V. cholerae by regulating expression of vps genes and its regulators vpsR and vpsT (3, 35, 53). There are 53 genes encoding proteins with GGDEF and/or EAL domains in the V. cholerae genome; more specifically, 31 genes encode GGDEF proteins, 12 encode EAL proteins, and 10 encode proteins with both domains on the same polypeptide (17, 21). We previously reported that the cellular levels of c-di-GMP are higher in the V. cholerae rugose variant than in the smooth variant, and expression levels of cdgA, cdgB, and cdgC were up-regulated in the rugose variant, whereas expression of cdgD and cdgE was down-regulated (35). Here we show that expression of cdgA, cdgD, and cdgE at wild-type rugose strain levels requires VpsT.

Expression of a large set of genes required for energy metabolism and nutrient transport was decreased in the RvpsT mutant. In addition, a large set of the differentially regulated genes between the RvpsT mutant and the wild-type rugose strain encode hypothetical and conserved hypothetical proteins (102 genes) or proteins of unknown function (7 genes). Thus, the function of ∼38% of the genes which are regulated by VpsT is unknown.

Recently, the effect of constitutive expression of CsgD, which is the homolog of VpsT in E. coli, was investigated (4). This study revealed that CsgD controls expression of genes that function in the modulation of intracellular nucleotide and nucleoside pools, genes encoding GGDEF/EAL family proteins, and genes involved in cold shock response (4). Our results revealed that VpsT regulates genes predicted to have similar functions in V. cholerae, suggesting that VpsT and CsgD control similar cellular processes.

Comparison of VpsT and VpsR regulons.

The response regulators VpsT and VpsR are required for vps gene expression and, in turn, formation of rugose colonies and biofilms (6, 58). To elucidate the processes that are controlled by each of the positive regulators and to determine the contribution of each regulator to the gene expression profile of the rugose variant, we also compared whole-genome expression patterns of the vpsR deletion mutant in the rugose genetic background (denoted RvpsR) to that of the wild-type rugose variant during exponential growth. Using the differential gene expression criteria described above, the expression of 191 genes (52% of the total differentially regulated genes) was determined to be lower in the RvpsR mutant than in the rugose variant, indicating that these genes require VpsR for their expression (see Table S2 in the supplemental material for a complete list). The expression of 175 genes (48%) was higher in the RvpsR mutant than in the rugose variant, indicating that their expression is normally repressed through the action of VpsR.

Differences in transcription profiles between the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants and the rugose variant were determined using scatter plot analysis. The graph revealed that 194 genes (comprising ∼43% of the differentially regulated genes) are regulated by both VpsT and VpsR and that 94 and 172 genes are regulated by only VpsT and VpsR, respectively (Fig. 1B). The genes that are regulated by both VpsT and VpsR were found in quadrants I and III (Fig. 1B), indicating that vpsT and vpsR regulate expression of a large set of genes with similar directionalities. The commonly regulated genes include vps genes, regulatory genes, genes required for purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis, genes required for energy metabolism and nutrient transport, and genes encoding hypothetical and conserved hypothetical proteins. Further analysis of gene expression profiles revealed that genes that are uniquely differentially expressed in either the RvpsT or RvpsR mutant were also differentially expressed in both mutants relative to the wild type but did not meet the criteria in our SAM analysis (≤3% false-positive discovery rate and ≥1.5-fold transcript abundance differences between the samples). Thus, the VpsR and VpsT regulons are identical in large part, but the magnitude of induction or repression of the genes regulated by them was, for the most part, greater for the RvpsR mutant than the RvpsT mutant. In particular, expression of vps-I (vpsA-K), vps intergenic-region genes, and the vps-II cluster genes (vpsL-Q) was reduced in the RvpsT mutant on average 4.7-, 8.6-, and 17.6-fold, respectively. In contrast, their expression decreased 9.1-, 22.6-, and 12.1-fold, respectively, in the RvpsR mutant relative to the rugose variant.

To further explore the relationship between vpsR and vpsT, we compared the whole-genome expression pattern of the RvpsR and RvpsT mutants to that of the RvpsT vpsR double mutant. The complete list of genes differentially regulated in the RvpsT vpsR double mutant relative to the rugose variant is provided in Table S3 in the supplemental material. Expression of only 7 and 49 genes was determined to be differentially regulated between the RvpsT vpsR and RvpsR mutants and the RvpsT vpsR and RvpsT mutants, respectively. The overall expression profile of the double mutant was most similar to that of the RvpsR mutant (Fig. 1A). We confirmed that vps gene expression in the double mutant is similar to that of the RvpsR mutant using qRT-PCR analysis (Table 2).

Characterization of biofilm-forming capacities of RvpsR and RvpsT in flow cell and static systems.

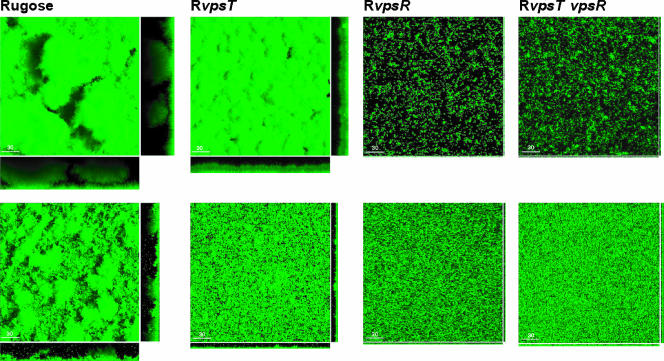

The well-established relationship between VPS production and biofilm formation led us to compare the biofilm-forming capacities of the RvpsR and RvpsT mutants and the rugose variant. We first analyzed biofilm formation using a once-through flow cell reactor and GFP-tagged strains. Analysis of biofilm structures formed by the RvpsT mutant in the once-through flow cell system revealed that the biofilm-forming capacity of the RvpsT mutant is markedly different from that of the rugose variant. However, the RvpsT mutant was still able to form well-developed biofilms with typical three-dimensional structures composed of pillars and channels (Fig. 2). In contrast, the structure of biofilms formed by the RvpsR or RvpsT vpsR mutant in the once-through flow cell system primarily consists of either single cells or small microcolonies attached to the substratum and are not well developed (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Characterization of biofilm formation under flow and nonflow conditions. Three-dimensional biofilm structures of the wild-type rugose strain and the RvpsT, RvpsR, and RvpsT vpsR strains formed after 24 h and 8 h postinoculation in a once-through flow cell (top row) and nonflow systems (bottom row), respectively. Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy, and top-down views (large panes) and orthogonal views (side panels) of biofilms are shown.

Under nonflow conditions, the rugose variant formed well-developed biofilms reaching an average height of 20 to 25 μm after 8 h of incubation under static growth conditions. In contrast, the RvpsT mutant formed less-developed biofilms composed of single cells and microcolonies, while the RvpsR and RvpsT vpsR mutants attached to surfaces mainly as single cells. These results are congruent with our previously published studies (6). Together, the results indicate that in a once-through flow cell system, where fresh nutrients are continuously provided and waste materials and extracellular signaling molecules (i.e., quorum-sensing signals) are removed from the system, the structures of RvpsT biofilms differ greatly from the ones formed under nonflow conditions. In contrast, both the RvpsR and RvpsT vpsR mutants are unable to form biofilms with three-dimensional structures under either condition. These findings suggest that in the absence of quorum-sensing signals that further reduce vps gene expression, there is enough vps expression to form a reasonably well-developed biofilm in RvpsT mutants in the once-through flow cell system. In contrast, in the static system, where RvpsT mutants are still sensitive and subject to quorum-sensing-mediated repression of vps gene expression, well-developed biofilms do not form. The target of the quorum sensing system could be vpsR, and repression may be exerted on vpsR either at the transcriptional level or at the posttranscriptional level by modulating the phosphorylation state of VpsR. In addition, HapR could affect vps gene expression directly by binding to the upstream regulatory regions of these genes (59).

Contribution of cdgA to the differences in vps gene expression between the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants.

To gain further insight into differences in vps gene expression and biofilm formation between the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants, we directly compared whole-genome expression patterns of RvpsT and RvpsR mutants during exponential growth (Table 3). We found that expression of 31 genes (78% of total differentially regulated genes) was increased in the RvpsT mutant relative to the RvpsR mutant. In particular, expression of the vps-I cluster (vpsA-K) and vps intergenic-region genes was higher in the RvpsT mutant on average 1.9- and 2.5-fold, respectively. On the other hand, expression of vps-II cluster genes (vpsL-Q) was not altered between the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants. We observed that expression of cdgA (VCA0074) was 1.7-fold higher in the RvpsT mutant than in the RvpsR mutant.

TABLE 3.

Genes that are differentially expressed in the RvpsR versus RvpsT mutants and in the RcdgA vpsR versus RcdgA vpsT mutantsa

| Gene and function | Descriptionb | Relative expression (n-fold)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RvpsR/RvpsT | RcdgA vpsR/RcdgA vpsT | ||

| VPS biosynthesis | |||

| VC0916 | Phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase | 0.23 | |

| VC0917 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase; wecB | 0.54 | |

| VC0918 | UDP-N-acetyl-d-mannosaminuronic acid dehydrogenase; epsD | 0.33 | |

| VC0919 | Serine acetyltransferase-related protein | 0.38 | |

| VC0922 | Hypothetical protein | 0.55 | |

| VC0924 | CapK protein; putative | 0.63 | |

| VC0925 | Polysaccharide biosynthesis protein; putative | 0.55 | |

| VC0926 | Hypothetical protein | 0.56 | |

| VC0927 | UDP-N-acetyl-d-mannosamine transferase; cpsF | 0.45 | |

| VC0928 | Hypothetical protein | 0.51 | 0.33 |

| VC0929 | Hypothetical protein | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| VC0930 | Hemolysin-related protein | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| VC0932 | Hypothetical protein | 0.58 | |

| VC0933 | Hypothetical protein | 0.47 | 0.43 |

| VC0935 | Hypothetical protein | 0.59 | |

| Metabolism | |||

| VC1341 | Acetyltransferase; putative | 0.64 | |

| VC1827 | Mannose-6-phosphate isomerase; manA2 | 2.15 | |

| VCA0677 | NapD protein; napD | 1.83 | |

| Transport and binding proteins | |||

| VC1820 | PTS system; fructose-specific IIA component; frvA | 5.96 | |

| VC1821 | PTS system; fructose-specific IIBC component; frwBC | 3.99 | |

| VC1826 | PTS system, fructose-specific IIABC component; fruA1 | 3.20 | |

| VCA0612 | Large-conductance mechanosensitive channel; mscL | 0.61 | |

| Hypothetical proteins | |||

| VC0132 | Hypothetical protein | 0.45 | |

| VC1262 | Hypothetical protein | 1.95 | 2.71 |

| VC1637 | Hypothetical protein | 0.61 | |

| VC1701 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.58 | 0.54 |

| VC1899 | Hypothetical protein | 0.43 | |

| VC2149 | Hypothetical protein | 2.25 | |

| VC2569 | Hypothetical protein | 0.58 | |

| VC2647 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.65 | |

| VCA0139 | Hypothetical protein | 0.58 | |

| VCA0296 | Hypothetical protein | 0.35 | |

| VCA0611 | Hypothetical protein | 0.65 | |

| VCA0645 | Hypothetical protein | 0.45 | |

| VCA0732 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.26 | 0.46 |

| VCA0849 | Hypothetical protein | 0.33 | 0.23 |

| Other functions | |||

| VC0194 | Glutathione gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase; ggt | 0.31 | |

| VC0219 | Ribosomal protein L33; rpmG | 0.61 | |

| VC1825 | Transcriptional regulator | 5.28 | |

| VC1888 | Hemolysin-related protein | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| VC1935 | CDP-diacylglycerol-glycerol-3-phosphate 3-phosphatidyltransferase-related protein | 0.51 | 0.24 |

| VCA0074 | GGDEF family protein; cdgA | 0.58 | |

| VCA0773 | Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 1.83 | |

| VCA0864 | Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 0.49 | |

Differentially expressed genes were determined using SAM software with ≥1.5-fold change in gene expression and a false discovery rate of ≤0.03 as criteria.

PTS, phosphotransferase.

cdgA is predicted to encode a 366-amino-acid polypeptide with a GGDEF domain located at the C terminus. Proteins containing GGDEF domains are predicted to function as diguanylate cyclase and are responsible for the generation of c-di-GMP (45). We recently have shown that c-di-GMP concentrations are increased in the rugose variant and that increased c-di-GMP in the cell can increase vps transcription and modulate colony rugosity (35). Furthermore, we had previously shown that cdgA is expressed at higher levels in the rugose variant and that its expression is decreased fivefold in the RvpsR mutant relative to the wild-type rugose variant (59). In addition, cdgA expression is 4.5-fold higher in the ShapR mutant than in the wild-type smooth variant (59). These findings indicated a possibility that cdgA may be responsible for the differential expression of vps genes between the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants.

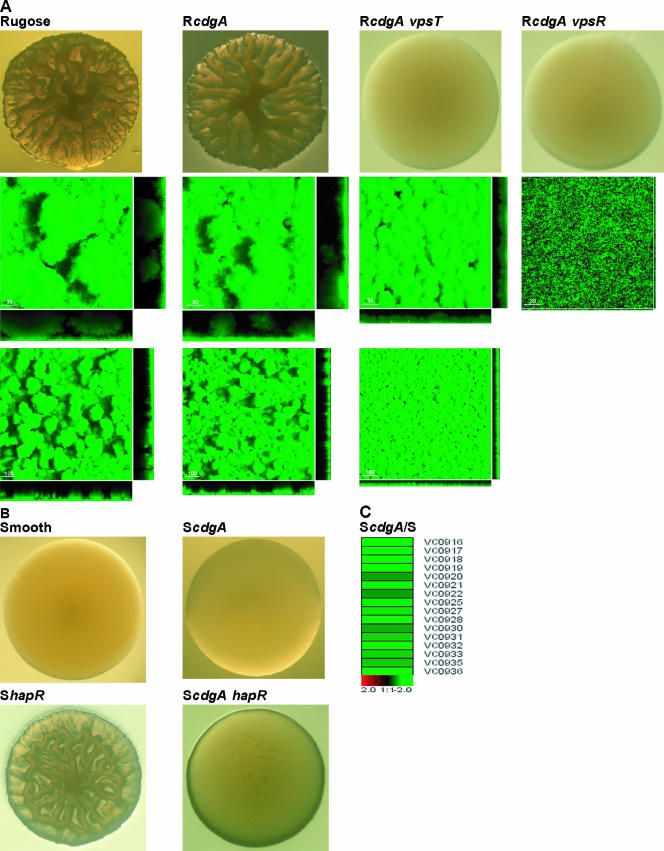

To determine if this was the case, we deleted cdgA in RvpsT and RvpsR genetic backgrounds, generating RcdgA vpsT and RcdgA vpsR mutants. We first determined whether mutating cdgA alters the differences in transcriptomes of RvpsT and RvpsR. To this end, we compared whole-genome expression patterns of RcdgA vpsT and RcdgA vpsR mutants during exponential growth to the pattern of the rugose variant and to each other (Table 3). Expression of only a very small set of genes (14 genes) was found to be differentially regulated between these mutants, and in particular vps-I genes were no longer differentially expressed between RcdgA vpsT and RcdgA vpsR mutants (Table 3), suggesting that cdgA contributes to differential vps-I gene transcription between RvpsT and RvpsR mutants. However, expression levels of vps intergenic-region genes (rbmA [VC0928], VC0929, VC0930, and VC0933), encoding proteins critical for formation of wild-type biofilm architecture, were 6.8-fold higher in the RcdgA vpsT mutant than in the RcdgA vpsR mutant (Table 3). To determine if the altered vps-I gene expression caused any changes either in colony morphology or in biofilm formation, we assayed for these phenotypes. Deletion of cdgA in RvpsT and RvpsR genetic backgrounds did not result in any changes in colonial morphology, indicating that vpsT and vpsR are epistatic to cdgA in the rugose genetic background for colony morphology (Fig. 3A). As we observed significant phenotypic differences between RvpsT and RvpsR mutants only in biofilms formed in the once-through flow cell system, we compared biofilms formed under such conditions. The biofilms of the RcdgA vpsT and RcdgA vpsR mutants were not significantly different than those of RvpsT and RvpsR single mutants (Fig. 2), and the difference in biofilm formation between the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants was maintained in the RcdgA vpsT and RcdgA vpsR mutants, respectively (Fig. 3A). Taken together, the results suggest that differences in vps-I expression are not the main cause for the altered biofilm-forming capacities of RvpsT and RvpsR mutants in the once-through flow cell system. The contribution of vps intergenic-region genes to the biofilm phenotypes of RvpsT and RvpsR mutants is under investigation.

Characterization of the role of CdgA on colony development, biofilm formation, and regulation of vps expression. (A) Colony morphology of rugose, RcdgA, RcdgA vpsT, and RcdgA vpsR strains grown on LB agar plates after 48 h of incubation at 30°C (top row). Three-dimensional biofilm structures of rugose, RcdgA, RcdgA vpsT, and RcdgA vpsR strains formed after 24 h postinoculation in once-through flow systems at high (second row) and low magnifications (third row) are shown. Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy and top-down views (large panels) and orthogonal views (side panels) of biofilms are shown. (B) Colony morphology of smooth, ScdgA, ShapR, and ScdgA hapR strains grown on LB agar plates after 48 h of incubation at 30°C. The expression profiles of vps genes in the ScdgA mutant relative to the smooth variant are presented using the log2-based color scale shown at the bottom of the panels (red, induced; green, repressed).

We reported earlier (35) that deletion of cdgA in the rugose genetic background has a subtle effect on rugose colonial morphology (Fig. 3A), and we show in this study that biofilm formation is also subtly affected, where the frequency and size of pillars were reduced in RcdgA biofilms relative to those of rugose biofilms. CdgA possibly possesses diguanylate cyclase activity and can contribute to vps gene transcription by modulating cellular c-di-GMP levels. We reasoned that due to an already high level of c-di-GMP in the rugose variant (due to another protein with a GGDEF domain [S. Beyhan and F. Yildiz, unpublished data]), the contribution of cdgA to vps gene expression could not be accurately determined in the rugose genetic background. The contribution of CdgA to vps gene expression in the rugose genetic background was small, as determined by qRT-PCR (Table 2). Thus, we deleted cdgA in the smooth genetic background (ScdgA) and compared its expression profile to that of the smooth variant. Expression of 61 genes was found to be differentially regulated (see Table S4 in the supplemental material).

In particular, we observed that expression levels of 16 out of 24 vps region genes (VC0916 to VC0939) were reduced 2.2-fold on average in an ScdgA mutant relative to the smooth variant, further showing that cdgA regulates vps gene expression (Fig. 3C). This finding was confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis. In the ScdgA mutant, transcription of vpsA and vpsL was decreased 5- and 4.5-fold, respectively, compared to the smooth wild type (Table 2). However, since vps levels are already low in the smooth variant, no significant differences in colony morphology were observed between the ScdgA mutant and the smooth variant (Fig. 3B). One way to increase vps gene expression in the smooth genetic background is to mutate hapR, which results in formation of rugose-like colonies. Expression of cdgA was shown to be higher in the smooth hapR mutant (ShapR) (59, 62). Thus, we hypothesized that cdgA is responsible for the increased vps transcription and, in turn, rugose colony formation in the ShapR mutant. To test this hypothesis, cdgA was deleted in the ShapR mutant, and colony morphology was analyzed. The ScdgA hapR mutant formed colonies with dramatically reduced rugosity (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these experiments indicate that cdgA contributes to vps gene expression and colony rugosity in V. cholerae and that the contribution depends on the genetic background utilized.

Characterization of genetic interactions between vpsR, vpsT, and hapR.

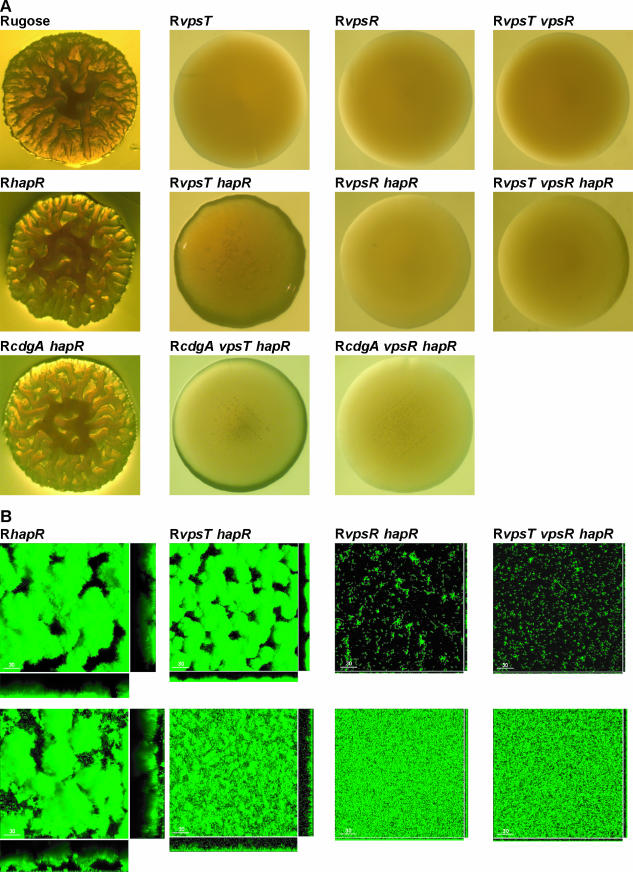

The transcriptional regulator HapR is a member of the quorum-sensing regulatory circuitry and negatively regulates vps gene expression and related phenotypes of rugose colony formation and biofilm formation (18, 59, 62). Differences in biofilm formation of the RvpsT and RvpsR mutants in the flow cell system where quorum-sensing signals could be eliminated prompted us to better characterize the regulatory circuitry controlling vps gene transcription. We hypothesized that mutating hapR in the RvpsT mutant should relieve quorum-sensing-dependent repression and increase vps gene expression, colony rugosity/compactness, and biofilm formation. We further hypothesized that hapR could influence vps gene expression in the RvpsT mutant through VpsR. If this was the case, the RvpsT vpsR hapR mutant should form smooth colonies and exhibit a decrease in biofilm formation, and biofilms of the triple mutant should be similar to the biofilm of the RvpsR mutant. To test this hypothesis, we mutated the hapR gene in the rugose genetic background and in the RvpsT, RvpsR, and RvpsT vpsR mutants, which will be referred to as the RhapR, RvpsT hapR, RvpsR hapR, and RvpsT vpsR hapR mutants, respectively.

We first characterized the mutants for colonial morphology. Mutation in hapR in the rugose genetic background enhanced colony rugosity (35, 59) (Fig. 4A). The RvpsT hapR mutant formed smooth-looking colonies with increased compactness and opacity relative to RvpsT mutants (Fig. 4A). However, colony morphology of the RvpsR hapR and RvpsT vpsR hapR mutants was completely flat and featureless, similar to that of the RvpsR mutant (Fig. 4A). As cdgA reduced colony rugosity in the ShapR mutant, we hypothesized that increased colony compactness and opacity of the RvpsT hapR mutant could be modulated by the cdgA gene product. To test this possibility, we generated RcdgA hapR, RcdgA vpsT hapR, and RcdgA vpsR hapR mutants. Introduction of a cdgA deletion into the RvpsT hapR mutant reduced colony compactness, suggesting that cdgA is responsible in part for the compact colony morphology of the RvpsT hapR mutant. In contrast, cdgA mutation in the RhapR or RvpsR hapR mutant did not cause any significant changes in colony morphology. It should be noted, however, that there are no differences in the growth rates of the mutants.

Characterization of colony morphology and biofilm formation. (A) Colony morphology of rugose, RvpsT, RvpsR, RvpsT vpsR, RhapR, RvpsT hapR, RvpsR hapR, RvpsT vpsR hapR, RcdgA hapR, RcdgA vpsT hapR, and RcdgA vpsR hapR strains grown on LB agar plates after 48 h of incubation at 30°C. (B) Three-dimensional biofilm structures of RhapR, RvpsT hapR, RvpsR hapR, and RvpsT vpsR hapR strains formed after 24 h and 8 h postinoculation in once-through flow cell (top row) and nonflow systems (bottom row), respectively, are shown. Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy and top-down views (large panes) and orthogonal views (side panels) of biofilms are shown.

We then determined the biofilm structure of each mutant using both a once-through flow cell system and nonflow systems. Under flow cell conditions, the structure of biofilms formed by the RhapR mutant was similar to that of the wild-type rugose strain (Fig. 2 and 4B). The RvpsT hapR biofilms formed in a flow cell system were in general similar to RvpsT biofilms such that the thicknesses of biofilms were between 10 and 15 μm (Fig. 2 and 4B). In contrast, the RvpsR hapR and RvpsR vpsT hapR mutants formed biofilms devoid of three-dimensional biofilm structures that were similar to RvpsR biofilms in the flow cell system. Thus, in the flow cell system, where quorum-sensing signals are absent, hapR mutation has little or no effect on the biofilm-forming profile of RvpsT and RvpsR mutants.

The biofilm-forming capacities of these mutants were also different from each other under nonflow conditions. The RhapR mutant formed biofilms with larger pillars relative to the biofilm of the wild-type rugose strain (Fig. 2 and 4B). The RvpsT hapR biofilms were more developed than the RvpsT biofilms, exhibiting small pillars reaching 6 μm in size (Fig. 2 and 4B). The biofilms formed by the RvpsR hapR and RvpsR vpsT hapR mutants did not differ significantly from the biofilm of the RvpsR mutant (Fig. 2 and 4B). The results together suggest that under nonflow conditions, which are conducive to accumulation of quorum-sensing signals, HapR decreases vps gene transcription and the biofilm-forming capacity of the RvpsT mutant. Furthermore, the results also showed that vpsR is epistatic to both vpsT and hapR in terms of their contribution to biofilm formation.

Transcriptome comparison of the RvpsT hapR and RvpsR hapR mutants.

Phenotypic analysis of the RvpsT hapR and RvpsR hapR double mutants discussed above suggested that the interactions of the positive regulators VpsT and VpsR with the negative regulator HapR are different. To gain a better understanding of the genes and processes regulated by each of the double mutants, we compared whole-genome expression patterns of the RvpsT hapR and RvpsR hapR double mutants to the pattern of the rugose variant and also to each other. The gene expression data were analyzed by the SAM program using the criteria described above to define significantly regulated genes. Expression of 41 genes was differentially regulated (21 genes induced and 20 genes repressed) between the RvpsT hapR mutant and the rugose variant. Expression of 466 genes was differentially regulated (256 genes induced and 210 genes repressed) between the RvpsR hapR mutant and the rugose variant.

Differences in transcription profiles between the RvpsT hapR and RvpsR hapR mutants versus the wild-type rugose variant were determined using scatter plot analysis. The graph revealed that 31 genes, comprising 7% of total differentially regulated genes, are regulated similarly by both the RvpsR hapR and RvpsT hapR mutants and that 435 and 10 genes, comprising 91% and 2% of the total differentially regulated genes, are regulated only by the RvpsR hapR and RvpsT hapR mutants, respectively (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Expression profiles of RhapR, RvpsR hapR, RvpsT hapR, and RvpsT vpsR hapR mutants. (A) Comparison of gene expression profiles of RvpsT hapR and RvpsR hapR mutants. The x and y axes denote the relative changes in gene expression (n-fold) in RvpsR hapR and RvpsT hapR mutants relative to the wild-type rugose strain, respectively, whereby each spot represents a gene that was differentially regulated 1.5-fold in at least one experiment. The plot area is divided into four regions (I to IV) based on the expression patterns in comparison to the rugose wild-type strain. Blue squares indicate genes differentially expressed only in the RvpsR hapR mutant, purple triangles indicate genes differentially expressed only in the RvpsT hapR mutant, and orange circles indicate genes differentially expressed in both mutants. (B) Differentially expressed genes in RhapR (lane 1), RvpsT hapR (lane 2), RvpsR hapR (lane 3), and RvpsT vpsR hapR (lane 4) mutants relative to the rugose variant are clustered by using Euclidian distance and average linkage hierarchical clustering. A compact view of clustered genes is presented using the log2-based color scale shown at the bottom of the panels (red, induced; green, repressed). Clusters that contain the genes required for VPS biosynthesis and pathogenesis are marked with black bars and labeled a and b, respectively. The expression profiles of these genes are also shown as separate heat maps. Expression profiles of genes required for VPS biosynthesis and virulence factor production are shown in clustered form in the enlarged views at right.

The genes that are commonly regulated by the RvpsT hapR and RvpsR hapR mutants include vps genes, comprising 45% of the total commonly regulated genes between these mutants. However, expression of vps genes was fivefold higher in the RvpsT hapR mutant relative to the RvpsR hapR mutant (Fig. 5B). We confirmed the expression of vps genes in each of these mutants using qRT-PCR. The results shown in Table 2 revealed that vpsA expression was significantly higher in the RvpsT hapR mutant than in the RvpsR hapR mutant and that vpsL expression was not detectable in the RvpsR hapR mutant. Transcription of vps genes in the RvpsR hapR and RvpsT vpsR hapR mutants was similar to that of the RvpsR mutant, further confirming that VpsR is the most downstream regulator in the VpsR, VpsT, and HapR signal transduction system and that VpsR positively regulates expression of the vps genes. Similarly, expression of eps genes, which are regulated coordinately with vps genes, is differentially regulated in both the RvpsT hapR and RvpsR hapR mutants, and expression of four of the eps genes was 1.6-fold higher in the RvpsT hapR mutant than in the RvpsR hapR mutant (see Table S5 in the supplemental material).

The genes that are differentially regulated in both the RvpsT hapR and RvpsR hapR mutants also included virulence genes. In V. cholerae, the major virulence factors that are required for infection are the cholera enterotoxin (produced by ctxAB genes) and the colonization factor toxin coregulated pilus (produced by tcp genes) (29). Transcription of the genes encoding cholera toxin and TCP is positively controlled by the regulatory proteins ToxR-ToxS and TcpP-TcpH, which control the expression of the most downstream regulator ToxT (5, 12, 13, 19, 42). Expression of tcpPH is also under the control of two other regulatory proteins, AphA and AphB (30, 32, 47). The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator HapR acts as a negative regulator of ctxAB and tcpA expression by negatively regulating expression of aphA and aphB (31).

Expression of four of the tcp genes was increased 1.8-fold on average in the RhapR mutant relative to the rugose variant; similarly, expression of aphA was increased 1.6-fold (Fig. 5B; see also Table S6 in the supplemental material). Expression of 13 of the genes encoding TCP and the genes encoding accessory colonization factors (acfB and acfC) was increased 3.7- and 2-fold on average, respectively, in the RvpsR hapR mutant relative to the rugose wild type (Fig. 5B; see Table S7 in the supplemental material). Expression of three of the tcp genes was increased 1.6-fold in the RvpsT hapR mutant relative to the rugose wild type (similar to hapR single mutant) (Fig. 5B; see Table S8 in the supplemental material). To validate the microarray results, we quantified the message levels of tcpA using qRT-PCR in the RhapR, RvpsT hapR, and RvpsR hapR mutants. In the RhapR and RvpsR hapR mutants the tcpA message level was 1.5- and 2.0-fold higher, respectively, than in the rugose wild type (Table 2). However, in the RvpsT hapR mutant, we did not observe any significant change in tcpA message level relative to the rugose wild type (Table 2). Message abundance for the gene encoding the most downstream transcriptional regulatory factors in the signal transduction system controlling virulence gene expression, toxT, was increased 2.9- and 1.7-fold in the RvpsR hapR and RvpsT hapR mutants relative to the wild-type rugose variant, respectively. Direct comparison of virulence gene expression levels between the RvpsR hapR and RvpsT hapR mutants revealed that expression of tcp genes, ctxA, and acfB was 2.5-, 1.6-, and 1.8-fold greater, respectively, in the RvpsR hapR mutant than in the RvpsT hapR mutant. Taken together, the results indicate that either deletion of vpsT causes a decrease or deletion of vpsR results in an increase in virulence gene expression in the RhapR mutant. There were no differences in virulence gene expression between the RhapR and RvpsT hapR mutants; however, expression of virulence genes was higher in the RvpsR hapR mutant than in the RhapR mutant, suggesting that VpsR negatively regulates virulence gene expression in the RhapR mutant. It should be noted that in the rugose variant, transcription of AphA is positively regulated by VpsR (59). We also observed that transcription of virulence genes in the RvpsT vpsR hapR mutant was similar to that of the RvpsT hapR mutant (Fig. 5B; see Table S9 in the supplemental material), suggesting that vpsT is epistatic to vpsR with respect to virulence gene expression in the RhapR mutant. The effect of VpsT on virulence gene expression is different from the effect on vps gene expression; however, at present we do not know the mechanism by which this regulation is mediated.

Conclusion.

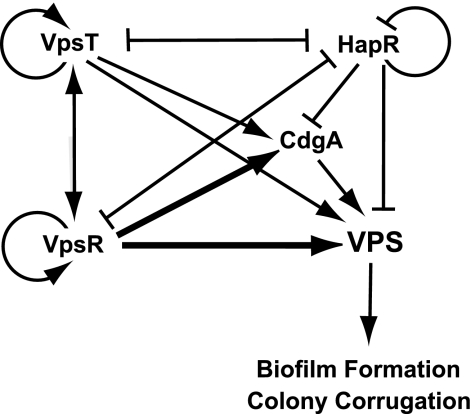

Various regulatory proteins act in concert to control transcription of rugosity-associated genes. The lack of clear epistatic relationships between vpsR, vpsT, and hapR suggests that parallel and/or converging pathways are involved in the regulation of rugosity-associated genes. A clear epistatic relationship between vpsR and vpsT was observed only under the conditions where the level of quorum-sensing signals is predicted to be low. Although it is yet to be determined if the interactions discussed below are direct or indirect, the studies discussed here support the model described in Fig. 6. Expression of vps genes and the regulators VpsR and VpsT is negatively controlled by HapR (59). Both VpsR and VpsT positively control transcription of vps genes; however, the magnitude of the transcriptional control of vps genes by VpsR is greater. VpsR and VpsT positively regulate their own and each other's expression (6). In this study, we showed that VpsT and VpsR negatively regulate either the transcription or the message abundance of hapR. We also found that CdgA is required for increased vps gene expression in the ShapR mutant. Transcription of cdgA is positively controlled by VpsR and VpsT and negatively controlled by HapR. The complexity of the regulation of vps gene expression indicates the importance of the phenotypic variation and associated lifestyle for the biology of V. cholerae.

FIG. 6.

Expression of rugosity-associated genes is controlled by a complex regulatory circuitry. The expression of vps genes is positively controlled by the regulators VpsR and VpsT, but the magnitude of regulation by VpsR is greater (denoted by darker lines). In contrast, the expression levels of vps genes are negatively controlled by HapR. Expression of VpsR and VpsT is negatively controlled by HapR; similarly, VpsR and VpsT negatively control hapR message levels, suggesting a presence of a regulatory loop. The expression of vps genes is positively controlled by CdgA. Transcription of cdgA is positively regulated by VpsR and VpsT and negatively regulated by HapR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from NIH (AI055987) and University of California Toxic Substances Research and Teaching Program to F.H.Y.

We thank members of the Yildiz laboratory for their comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 October 2006.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, A., J. A. Johnson, A. A. Franco, D. J. Metzger, T. D. Connell, J. G. Morris, Jr., and S. Sozhamannan. 2000. Mutations in the extracellular protein secretion pathway genes (eps) interfere with rugose polysaccharide production in and motility of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 68:1967-1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao, Y., D. P. Lies, H. Fu, and G. P. Roberts. 1991. An improved Tn7-based system for the single-copy insertion of cloned genes into chromosomes of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 109:167-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyhan, S., A. D. Tischler, A. Camilli, and F. H. Yildiz. 2006. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J. Bacteriol. 188:3600-3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brombacher, E., A. Baratto, C. Dorel, and P. Landini. 2006. Gene expression regulation by the curli activator CsgD protein: modulation of cellulose biosynthesis and control of negative determinants for microbial adhesion. J. Bacteriol. 188:2027-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll, P. A., K. T. Tashima, M. B. Rogers, V. J. DiRita, and S. B. Calderwood. 1997. Phase variation in tcpH modulates expression of the ToxR regulon in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1099-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casper-Lindley, C., and F. H. Yildiz. 2004. VpsT is a transcriptional regulator required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and the development of rugose colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 186:1574-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chirwa, N. T., and M. B. Herrington. 2003. CsgD, a regulator of curli and cellulose synthesis, also regulates serine hydroxymethyltransferase synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiology 149:525-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chirwa, N. T., and M. B. Herrington. 2004. Role of MetR and PurR in the activation of glyA by CsgD in Escherichia coli K-12. Can. J. Microbiol. 50:683-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi, K. Y., and H. Zalkin. 1990. Regulation of Escherichia coli pyrC by the purine regulon repressor protein. J. Bacteriol. 172:3201-3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christen, M., B. Christen, M. Folcher, A. Schauerte, and U. Jenal. 2005. Identification and characterization of a cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase and its allosteric control by GTP. J. Biol. Chem. 280:30829-30837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lorenzo, V., and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol. 235:386-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiRita, V. J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1991. Periplasmic interaction between two membrane regulatory proteins, ToxR and ToxS, results in signal transduction and transcriptional activation. Cell 64:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiRita, V. J., C. Parsot, G. Jander, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1991. Regulatory cascade controls virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5403-5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faruque, S. M., M. J. Albert, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1301-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faruque, S. M., K. Biswas, S. M. Udden, Q. S. Ahmad, D. A. Sack, G. B. Nair, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2006. Transmissibility of cholera: in vivo-formed biofilms and their relationship to infectivity and persistence in the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:6350-6355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fullner, K. J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1999. Genetic characterization of a new type IV-A pilus gene cluster found in both classical and El Tor biotypes of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 67:1393-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galperin, M. Y., A. N. Nikolskaya, and E. V. Koonin. 2001. Novel domains of the prokaryotic two-component signal transduction systems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammer, B. K., and B. L. Bassler. 2003. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 50:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hase, C. C., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. TcpP protein is a positive regulator of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:730-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He, B., K. Y. Choi, and H. Zalkin. 1993. Regulation of Escherichia coli glnB, prsA, and speA by the purine repressor. J. Bacteriol. 175:3598-3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson, I. R., P. Owen, and J. P. Nataro. 1999. Molecular switches—the ON and OFF of bacterial phase variation. Mol. Microbiol. 33:919-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heydorn, A., B. K. Ersboll, M. Hentzer, M. R. Parsek, M. Givskov, and S. Molin. 2000. Experimental reproducibility in flow-chamber biofilms. Microbiology 146:2409-2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hood, M. A., and P. A. Winter. 1997. Attachment of Vibrio cholerae under various environmental conditions and to selected substrates. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 22:215-223. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huq, A., E. B. Small, P. A. West, M. I. Huq, R. Rahman, and R. R. Colwell. 1983. Ecological relationships between Vibrio cholerae and planktonic crustacean copepods. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 45:275-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huq, A., P. A. West, E. B. Small, M. I. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 1984. Influence of water temperature, salinity, and pH on survival and growth of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae serovar O1 associated with live copepods in laboratory microcosms. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 48:420-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islam, M., B. Drasar, and R. Sack. 1993. The aquatic environment as a reservoir of Vibrio cholerae—a review. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 11:197-206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islam, M. S., Z. Rahim, M. J. Alam, S. Begum, S. M. Moniruzzaman, A. Umeda, K. Amako, M. J. Albert, R. B. Sack, A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 1999. Association of Vibrio cholerae O1 with the cyanobacterium, Anabaena sp., elucidated by polymerase chain reaction and transmission electron microscopy. Trans R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:36-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaper, J. B., J. G. Morris, Jr., and M. M. Levine. 1995. Cholera. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:48-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 2001. Overlapping binding sites for the virulence gene regulators AphA, AphB and cAMP-CRP at the Vibrio cholerae tcpPH promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 41:393-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 2002. Regulation of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae by quorum sensing: HapR functions at the aphA promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1135-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 1999. A Vibrio cholerae LysR homolog, AphB, cooperates with AphA at the tcpPH promoter to activate expression of the ToxR virulence cascade. J. Bacteriol. 181:4250-4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenz, D. H., M. B. Miller, J. Zhu, R. V. Kulkarni, and B. L. Bassler. 2005. CsrA and three redundant small RNAs regulate quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1186-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenz, D. H., K. C. Mok, B. N. Lilley, R. V. Kulkarni, N. S. Wingreen, and B. L. Bassler. 2004. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118:69-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim, B., S. Beyhan, J. Meir, and F. H. Yildiz. 2006. Cyclic-diGMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 60:331-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, Z., A. Hsiao, A. Joelsson, and J. Zhu. 2006. The transcriptional regulator VqmA increases expression of the quorum-sensing activator HapR in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 188:2446-2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorenz, E., and G. V. Stauffer. 1996. RNA polymerase, PurR and MetR interactions at the glyA promoter of Escherichia coli. Microbiology 142:1819-1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matz, C., D. McDougald, A. M. Moreno, P. Y. Yung, F. H. Yildiz, and S. Kjelleberg. 2005. Biofilm formation and phenotypic variation enhance predation-driven persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:16819-16824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng, L. M., and P. Nygaard. 1990. Identification of hypoxanthine and guanine as the co-repressors for the purine regulon genes of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2187-2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller, M. B., K. Skorupski, D. H. Lenz, R. K. Taylor, and B. L. Bassler. 2002. Parallel quorum sensing systems converge to regulate virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Cell 110:303-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller, V. L., R. K. Taylor, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Cholera toxin transcriptional activator toxR is a transmembrane DNA binding protein. Cell 48:271-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris, J. G., Jr., M. B. Sztein, E. W. Rice, J. P. Nataro, G. A. Losonsky, P. Panigrahi, C. O. Tacket, and J. A. Johnson. 1996. Vibrio cholerae O1 can assume a chlorine-resistant rugose survival form that is virulent for humans. J. Infect. Dis. 174:1364-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rice, E. W., C. J. Johnson, R. M. Clark, K. R. Fox, D. J. Reasoner, M. E. Dunnigan, P. Panigrahi, J. A. Johnson, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 1992. Chlorine and survival of “rugose” Vibrio cholerae. Lancet 340:740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryjenkov, D. A., M. Tarutina, O. V. Moskvin, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J. Bacteriol. 187:1792-1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt, A. J., D. A. Ryjenkov, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J. Bacteriol. 187:4774-4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skorupski, K., and R. K. Taylor. 1999. A new level in the Vibrio cholerae ToxR virulence cascade: AphA is required for transcriptional activation of the tcpPH operon. Mol. Microbiol. 31:763-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smits, W. K., O. P. Kuipers, and J. W. Veening. 2006. Phenotypic variation in bacteria: the role of feedback regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:259-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steiert, J. G., C. Kubu, and G. V. Stauffer. 1992. The PurR binding site in the glyA promoter region of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 78:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steiert, J. G., R. J. Rolfes, H. Zalkin, and G. V. Stauffer. 1990. Regulation of the Escherichia coli glyA gene by the purR gene product. J. Bacteriol. 172:3799-3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sturn, A., J. Quackenbush, and Z. Trajanoski. 2002. Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 18:207-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamplin, M. L., A. L. Gauzens, A. Huq, D. A. Sack, and R. R. Colwell. 1990. Attachment of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 to zooplankton and phytoplankton of Bangladesh waters. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 56:1977-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tischler, A. D., and A. Camilli. 2004. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 53:857-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tusher, V. G., R. Tibshirani, and G. Chu. 2001. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5116-5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vance, R. E., J. Zhu, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. A constitutively active variant of the quorum-sensing regulator LuxO affects protease production and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 71:2571-2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wai, S. N., Y. Mizunoe, A. Takade, S. I. Kawabata, and S. I. Yoshida. 1998. Vibrio cholerae O1 strain TSI-4 produces the exopolysaccharide materials that determine colony morphology, stress resistance, and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 64:3648-3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White, B. P. 1938. The rugose variant of Vibrios. J. Pathol. 46:1-6. [Google Scholar]