Abstract

Sodium currents are essential for the initiation and propagation of neuronal firing. Alterations of sodium currents can lead to abnormal neuronal activity, such as occurs in epilepsy. The transient voltage-gated sodium current mediates the upstroke of the action potential. A small fraction of sodium current, termed the persistent sodium current (INaP), fails to inactivate significantly, even with prolonged depolarization. INaP is activated in the subthreshold voltage range and is capable of amplifying a neuron's response to synaptic input and enhancing its repetitive firing capability. A burgeoning literature is documenting mutations in sodium channels that underlie human disease, including epilepsy. Some of these mutations lead to altered neuronal excitability by increasing INaP. This review focuses on the pathophysiological effects of INaP in epilepsy.

Ionic Channels and Excitability

Neuronal firing is controlled by numerous ionic conductances that interact to produce a wide array of threshold and subthreshold behaviors. The foundation of the understanding of neuronal firing comes from the pioneering work of Hodgkin and Huxley, who showed that the action potential upstroke is due to the rapid influx of sodium ions (1). Sodium influx through specific ion channels in the neuronal membrane causes a depolarizing inward current. Once open, sodium channels inactivate and cannot pass further current until they recover from inactivation. Sodium channel inactivation, in conjunction with outward current through potassium channels, allows the membrane potential to repolarize to the resting level.

In the past decade, an enormous expansion in the knowledge of the diverse ion channels that contribute to the regulation of neuronal firing has occurred (2). In addition to the transient sodium and potassium currents described by Hodgkin and Huxley (1), channels for a variety of ions have been described, including Ca2+ and Cl–; furthermore, channels that pass multiple ions, such as the hyperpolarization-activated cation current Ih (3), have been identified to play critical roles in regulating neuronal excitability. Ion channels are distributed differently in different parts of the neuron, allowing specific excitability profiles of dendrites, soma, initial segment, and axon (4). Ion channel expression and distribution also varies as a function of development (5), and each neuron class is endowed with a distinct electrical personality (6). Epilepsy emerges from abnormal activity of neuronal networks. However, hyperexcitability on many levels, including altered ion channel function, contributes to the seizure-prone state.

As integral membrane proteins, ion channels are under genetic control, and mutations are responsible for diverse human diseases, ranging from cystic fibrosis to cardiac arrhythmias to migraine (7, 8). In neurons, channelopathies often mediate paroxysmal alterations in function. Inherited forms of epilepsy constitute a prime example of channelopathies in which ion channel dysfunction alters neuronal excitability. Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition that can result from an acquired brain insult or from an inherited error in voltage- or ligand-gated ion channel function (9–11). Since the first voltage-gated ion channel defect in human epilepsy was reported, involving a potassium channel mutation that caused benign familial neonatal convulsions (12), numerous genetic mutations have been discovered in families with epilepsy. Some inherited epilepsies might even result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors (13).

This review focuses on sodium channels. The normal function and structure of sodium channels are reviewed as a preface to discussion of sodium channel mutations and resultant epilepsy syndromes. While other recent reviews discuss the wider spectrum of sodium channel mutations associated with epilepsy (10, 11, 14–16), this review focuses on one type of sodium current presently receiving increased attention as a factor in inherited epilepsies—it is the slowly inactivating or noninactivating sodium current, known as the persistent sodium current (INaP).

Transient and Persistent Sodium Currents

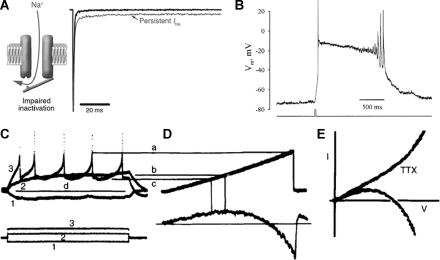

Voltage-dependent sodium current involves a transient inward flux of Na+ that depolarizes the cell membrane. The sodium channel varies among three functional states, depending upon the membrane potential: closed, open (activated), and inactivated. The current passing through open sodium channels has rapid kinetics, reaching its peak in less than a millisecond and declining to baseline within a few milliseconds. The kinetics and all-or-none threshold behavior of the transient sodium current makes it well suited to mediate the upstroke of the neuronal action potential. Some sodium current persists after the rapid decay of the transient sodium current (Figure 1A, arrows). INaP ordinarily accounts for about 1% of the peak inward sodium current (17). Despite its small amplitude compared with peak sodium current, INaP can alter firing behavior profoundly, especially in the subthreshold voltage range. INaP can be activated by small synaptic depolarizations and can then augment those potentials. Since the voltage range in which INaP is activated is traversed in the interspike interval in an action potential train, INaP can facilitate repetitive firing. INaP maintains prolonged, depolarizing plateau potentials in many neuron types (Figure 1B). Clearly, an increase of only a few percent in the sodium current can dramatically alter cell firing and facilitate hyperexcitability, as in seizure behavior.

FIGURE 1.

A. Left—Schematic of persistent sodium current traversing a channel with incomplete (impaired) inactivation, as likely occurs in many epilepsy-related sodium channel mutations. Right—Current traces depicting the fast transient sodium current (downward spike) and persistent sodium current, reflecting the long-lasting increase in a small fraction of sodium current that can influence repetitive firing, synaptic integration, and threshold for action potential generation (reprinted with permission from J Clin Invest[reference 14]).B. Current clamp record of a plateau potential, mediated by persistent sodium current, in a layer V pyramidal neuron with potassium and calcium currents blocked. The sustained, depolarizing plateau potential long outlasts the brief current pulse (lower trace). The gradual decline of the plateau and eventual return of regenerative action potentials implies a very slow recovery of sodium channels from fast inactivation (reprinted with permission from J Neurophysiol[reference 41]).C–E. Persistent sodium current demonstrated in current clamp (panel C) and single-electrode ramp voltage-clamp (panels D and E) recordings from a single layer V neocortical neuron. In panels C and D, upper traces are voltage and lower traces are current. Panel C shows voltage responses to 200-millisecond hyperpolarizing (traces 1) and depolarizing current pulses (traces 2 and 3). At subthreshold voltages and voltages traversed by spike afterpotentials during repetitive firing (indicated by lines b and c, respectively), persistent inward current is generated (points b and c in panel D). Panel E shows current traces in response to ramp voltage commands (not shown), superimposed on a current–voltage plot. With TTX application, this rectification is eliminated, verifying that the inward current is mediated by voltage-sensitive sodium channels (adapted with permission from Brain Res[reference 20]).

Function of INaP in Cell Firing and Its Regulation

The existence of INaP was first suggested by current clamp experiments in hippocampal (18) and cerebellar (19) neurons, in which prolonged depolarizing current pulses produced an inward rectification of the membrane potential and sustained plateau potentials when other ionic conductances (e.g., potassium, calcium) were blocked. Voltage clamp experiments first established the identity of the current underlying this inward rectification as INaP (20, 21). Figure 1C and D demonstrate that in neocortical pyramidal layer V neurons, an inward current is activated at exactly the appropriate voltage range to augment depolarization and facilitate repetitive firing. The elimination of this inward rectification by the anesthetic agent QX-314 (22) or by external application of tetrodotoxin (TTX) (19) establishes that the underlying current is carried by sodium ions (Figure 1E). Unfortunately, there is no unique pharmacological blocker of INaP. TTX blocks both the transient and persistent sodium currents, which is not surprising since both currents pass through from the same channel protein; the two currents differ in their kinetics because of different modes of gating rather than because of separate channel proteins (23).

In addition to hippocampus, cerebellum, and neocortex, INaP has now been found on several other mammalian neuron types, including thalamus (24), inferior olive (25), entorhinal cortex (26), mesencephalic V nucleus (27), hypoglossal nucleus (28), and even glia (29). INaP plays critical roles in several aspects of neuronal function of many cell types, amplifying subthreshold oscillations and synaptic potentials as well as facilitating repetitive firing (30–32). INaP adds to synaptic current to boost membrane potential toward threshold for action potential generation. INaP is localized on neuronal dendrites, where it boosts distal synaptic potentials to allow them to reach the soma (33); on the proximal axon, where it can profoundly affect spike initiation (34); as well as on peripheral axons (35, 36). Its high density near the axon initial segment is an optimal location for control of repetitive firing behavior (30). Experimental and modeling studies have shown that INaP amplifies the spike afterhyperpolarization and increases the regularity of repetitive firing, thus governing the spatiotemporal pattern of neuronal firing in potentially opposite directions (37). INaP can be modulated by neurotransmitters and by phosphorylation, adding to its complex role in the regulation of spike timing and firing (38, 39). Theoretically, INaP also could participate in pathophysiological neuronal firing (e.g., epileptic firing), since it keeps the membrane depolarized longer. In neocortex, the robust presence of INaP in layer V neurons (compared with neurons of layer II/III (40)) enhances excitability in neurons that comprise the neocortical output circuit and are critical to the spread of epileptic activity.

A persistent current can arise through several mechanisms, including increased channel open times, decreased inactivation, change in voltage dependence of activation or inactivation, or late/delayed channel openings. INaP could be generated either through distinct sodium channel subtypes or through different gating modes of a single sodium channel type. The latter hypothesis is supported by single-channel recordings (23, 41). In addition to the usual short latency and brief opening that characterize the transient INaP, two forms of late/delayed openings were identified: brief, late openings and bursts of late openings, lasting for several seconds. These late openings suggest that INaP is generated by different kinetic modes of the same sodium channel, with the same channel occasionally entering an open state that lacks fast inactivation (42). INaP probably is not due to a “window current,” reflecting overlap between the Hodgkin–Huxley activation and inactivation curves (i.e., a voltage range in which some channels are activated, while others are not yet inactivated); this window current occurs only over a restricted voltage range (30).

Structure and Genetics of Sodium Channels

Voltage-gated sodium channels are heteromers composed of α and β subunits (43). These channels are highly conserved through evolution and have similar structure and function in several excitable tissues, including cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, and neurons. Each α subunit is a large polypeptide of about 2,000 amino acid residues composed of four homologous repeats or domains (I-IV), each repeat consisting of six transmembrane segments (S1–S6). The four domains form the channel pore through which the sodium ion passes. The α subunit serves several functions including voltage sensor (positively charged S4 segments of each domain), ion selectivity filter/pore (hydrophobic S5–S6 segments of each domain), and inactivation gate at the inner mouth of the channel (an intracellular loop connecting domains III and IV). Each α subunit is associated with one or more β subunits; four β subunits have been described, β1–β4 (15). The β subunit is a single transmembrane segment that has an extracellular IgG-like loop and an intracellular C terminus. β subunits modulate α subunit function by altering their voltage dependence, kinetics, and cell surface expression.

As integral membrane proteins, each subunit is encoded by a specific gene. At least 13 genes encode sodium channel α or β subunits in the CNS. Mutations of these genes cause altered excitability regulation in every tissue in which sodium channels are found. For example, in skeletal muscle, mutation of SCN4A, which codes for sodium channel NaV1.4, results in paroxysmal muscle hyperexcitability in syndromes such as hyperkalemic periodic paralysis and paramyotonia congenita (7, 14). In cardiac muscle, mutation of SCN5A causes several distinct disorders of cardiac rhythm, including long QT syndrome. In the central nervous system, SCN1A, SCN2A, and SCN3A code for α subunits of sodium channel isoforms NaV1.1, 1.2, and 1.3, respectively. These three genes are clustered on chromosome 2q24. SCN8A also is found in brain and is located on chromosome 12q13. SCN1B, on chromosome 19q13, codes for the β1 subunit, which typically is associated with the α subunit to form the intact channel. Other genes coding for sodium channel subtypes are specific for the peripheral nervous system and could contribute to disorders of axonal excitability (44).

Epilepsy Syndromes with Sodium Channel Mutations and Role of INaP in Epilepsy

Epilepsy can arise from either a genetic mutation of a sodium channel gene or from an acquired insult to normal sodium channels—each mechanism is described here.

Inherited Channelopathies

Sodium channel mutations have been identified in several families with inherited epilepsy, with the syndromes reflecting a spectrum of clinical severity. Although each mutation is rare, new mutations are being revealed at a striking rate, adding to the opportunity to establish specific genotype–phenotype correlations. However, despite a common phenotype (e.g., seizures), the syndromes are clinically diverse in terms of epilepsy severity, seizure type, age of onset, and neurological outcome. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms also are quite diverse. Table 1 lists the number of reported patients with sodium channel mutations underlying their epilepsy syndromes (up to 2005), thus depicting the distribution of genetic defects (15).

TABLE 1.

Number of Epilepsy Patients Identified with Various Sodium Channel Mutations (Adapted with Permission from J Clin Invest 2005;115:2010–2017)

| Epilepsy Syndrome | SCN1A | SCN2A | SCN1B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy | 150 | 1 | 0 |

| Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus | 13 | 1 | 2 |

| Intractable childhood epilepsy with generalized tonic–clonic seizures | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Benign familial neonatal–infantile seizures | 0 | 6 | 0 |

Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) is characterized by febrile seizures early in life but afebrile seizures occur after 6 years of age when typical febrile seizures have subsided (45). The seizure types at older ages span the phenotypic range, including partial, generalized tonic–clonic, absence, and myoclonic. Affected individuals often have fairly mild epilepsy. GEFS+ families are genetically heterogeneous, with documented sodium channel mutations in SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN1B, as well as in one GABA receptor subunit (GABRG2). The first family in which a GEFS+ mutation was identified had a defective SCN1B gene. The mutation, C121W, consists of a substitution of a highly conserved cysteine residue (C) by a tryptophan (W) in amino acid 121. The substitution disrupts a disulphide bridge in the extracellular loop of the β1 subunit and results in slowed channel inactivation and inability to modulate channel gating (46). Therefore, this mutation is an example of a sodium channel loss-of-function mutation. Mice with null mutations of the β1 subunit develop spontaneous seizures and other neurological problems (47).

Subsequently, other families with GEFS+ were linked to chromosome 2q24-33, where a cluster of sodium channel α subunits resides. Most mutations appear in the S4 voltage sensor region of SCN1A. A variety of functional defects was found, including an increase in INaP, therefore representing a gain-of-function mutation (48). Increased INaP could facilitate seizures for the reasons discussed above—enhancement of repetitive firing, heightened depolarization in the sub- and near-threshold voltage range, and reduced threshold for action potential firing. However, the absence of a gain-of-function mutation in many SCN1A patients suggests that this mechanism is not the full explanation. Other pathophysiological defects have been reported in GEFS+, including shifts in the voltage dependence of activation or inactivation (49, 50). Even mutations that, on the surface, decrease sodium channel excitability (e.g., positive shift in the voltage dependence of activation and slow recovery from inactivation) can predispose to epilepsy, for reasons that are not yet completely understood (51).

In addition, a single patient with a mutation in SCN2A was reported to have slowed inactivation and persistent repetitive firing, also suggesting a gain-of-function (52). In the Q54 transgenic mouse, which harbors an SCN2A mutation, sodium channel inactivation is impaired and a prominent INaP is seen when the mutant gene is expressed in an oocyte expression system. In recordings from hippocampal CA1 neurons of these mice, enhanced INaP was documented before spontaneous seizures developed, rendering this animal model promising for investigation of sodium channel pathophysiological derangements in genetic epilepsy (53). The model also is being used to study the effect of modifier genes on epilepsy development and the interactions between multiple epilepsy gene mutations (54).

A second epilepsy syndrome with sodium channel mutations is severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI) or Dravet syndrome. As the name implies, affected children initially develop febrile seizure during the first year of life, followed by intractable seizures (generalized tonic–clonic, myoclonic) and cognitive impairment. About one-third of children with SMEI have mutations in SCN1A, the majority being frameshift or missense, especially at the pore region (S5–S6) (55, 56). These mutations result in truncated protein and, therefore, are associated with a severe phenotype.

A variant of SMEI, recently described, is called intractable childhood epilepsy with generalized tonic–clonic seizures (ICEGTC). This syndrome differs from SMEI in that children lack myoclonic seizures and have fewer cognitive difficulties. ICEGTC is associated with SCN1A missense mutations, whereas SMEI is associated with nonsense, frameshift, and missense mutations, endowing the latter syndrome with a more severe phenotype (57, 58). Several, but not all, ICEGTC mutants exhibit increased INaP (59). Finally, a new benign syndrome termed benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures (BFNIS) is characterized by seizures that remit by 1 year of age and are not associated with any long-term neurological sequelae; six different SCN2A mutations have been reported (60). Four of those mutations have been characterized biophysically. In transfected neocortical neurons in primary culture, mutated channels had abnormal gating properties, predisposing to enhanced neuronal excitability by increasing sodium current via a positive shift of the inactivation curve or a negative shift of the activation curve (61). The consistent gain-of-function of these mutations contrasts with SCN1A mutations, in which sodium channel function may be increased or decreased.

It is difficult to generalize about defective channel functions associated with sodium channel mutations, since there is an inexact correlation between phenotype and genotype. Even within gain-of-function mutations (i.e., with increased INaP), there is heterogeneity of pathophysiological mechanisms (Table 2). Both loss- and gain-of-function mutations are seen in GEFS+, so the seizure susceptibility in this syndrome cannot always be ascribed to persistent sodium current. GEFS+ mutations are usually of the missense variety, while SMEI mutations involve frameshift and nonsense mutations as well, correlating with the more severe phenotype. Functionally, most SMEI mutations are loss-of-function, except with missense mutations for which increased INaP is seen (62). As highlighted in the accompanying commentary by Cooper, sodium channel loss-of-function mutations can result in neuronal hyperexcitability (and hence, epilepsy) by virtue of relative localization of sodium channel subtypes (with subtle differences in biophysical properties) along different parts of the neuron as well as on different cell types within neuronal circuits. For example, intriguing recent results from SCN1A−/− null mutant mice and heterozygous SCN1A+/− mice showed reduced sodium currents in hippocampal inhibitory neurons but not in pyramidal neurons (63). This selective distribution of mutations would decrease the firing of GABAergic inhibitory neurons, thus increasing excitability of the principal excitatory neurons. The enormous diversity of biophysical mechanisms underlying seizure predisposition in genetic epilepsies remains to be clarified, and explanations will need to take into account neuronal network behavior (64); channel function/dysfunction in multiple types of neurons, interneurons, and glia; and the developmental stage of the patient (65, 66).

TABLE 2.

Selected Sodium Channel Mutations Associated with an Increase in INaP

| Gene | Epilepsy Syndrome | Mutation | Mechanism of Increased INaP | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCN1A | GEFS+ | T875M | Impaired (enhanced) slow inactivation | 48 |

| Acceleration of activation | 73 | |||

| SCN1A | GEFS+ | W1204R | Impaired inactivation | 48 |

| Hyperpolarized shifts in voltage-dependent activation and inactivation | 49 | |||

| SCN1A | GEFS+ | R1648H | Accelerated recovery from inactivation | 48, 74 |

| Increased probability of late reopenings | ||||

| Increased fraction of channels with prolonged open times | ||||

| SCN1A | SMEI | R1648C | Impairment of fast inactivation | 62 |

| F1661S | ||||

| SCN1A | ICEGTC | V1611F | Abnormal voltage-dependent activation with hyperpolarizing shift | 59 |

| P1632S | ||||

| F1808L |

GEFS+, generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus; SMEI, severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy; ICEGTC, intractable childhood epilepsy with generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Acquired Channelopathies

In genetically normal animals, sodium channel dysfunction can occur as a consequence of altered channel expression or function. Two studies have provided evidence that limbic seizures induce an increase in INaP. In rats subjected to lithium-pilocarpine–induced status epilepticus, whole cell recordings of layer V entorhinal cortex neurons showed significantly larger INaP compared with age-matched controls—at a time point coinciding with the onset of spontaneous recurrent seizures (67). These results presume that status epilepticus caused the increased persistent current, which in turn contributes to the emergence of spontaneous seizures. In subicular burst firing neurons resected from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, a large increase of INaP has been recorded, with an amplitude up to half of the total sodium current (68). In this study, the increased INaP could partially explain the enhanced epileptogenicity in the subicular region (69, 70). However, lacking control (i.e., nonepileptic) neurons, these authors used rat subicular neurons as a comparison, which exhibited less INaP. A complete understanding of whether epileptogenesis causes expression of INaP or whether INaP was dysfunctional prior to seizures and led to the seizure-prone state (or both) remains to be determined.

Anticonvulsant Effects on INaP

Sodium channels are targets for many antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) as well as for anesthetic agents and antiarrhythmic agents. Given the increasing role of INaP in epilepsy, it is a reasonable target for AEDs as well. The effects of several AEDs on INaP have been evaluated (Table 3) and have been found to reduce INaP at clinically appropriate doses. At present, none of these AEDs is specific for INaP, but several of them reduce INaP at a dose lower than that which alters the transient sodium current. Of note, antiabsence drugs, such as ethosuximide, do not affect INaP. Another mechanism that is just beginning to be explored is whether a genetic mutation alters channel sensitivity to AEDs; in the C121Wβ1 mutation, mutant channels were less sensitive to inhibition by phenytoin (71). Finally, any drug that reduces sodium current in a loss-of-function mutation, thereby further reducing even essential sodium current, must be viewed with caution, as is the case for lamotrigine in SMEI (72).

TABLE 3.

Examples of the Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs on INaP

Conclusions

The INaP is a noninactivating component of the total sodium current that dramatically affects the excitability of neurons and other excitable tissues. This current, activated at subthreshold voltages, has been shown to play important roles in the regulation of neuronal firing. Some sodium channel mutations associated with human epilepsy syndromes exhibit increased INaP, but other sodium channel mutations lead to seizures by alternative pathophysiological mechanisms. Future research will be focused on identifying exact biophysical defects by which INaP alterations cause neuronal hyperexcitability and epilepsy and in finding specific therapeutic agents that diminish this current.

References

- 1.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol (Lond) 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai HC, Jan LY. The distribution and targeting of neuronal voltage-gated ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:548–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poolos NP. The h-channel: a potential channelopathy in epilepsy? Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trimmer JS, Rhodes KJ. Localization of voltage-gated ion channels in mammalian brain. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:477–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.113328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moody WJ, Bosma MM. Ion channel development, spontaneous activity, and activity-dependent development in nerve and muscle cells. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:883–941. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steriade M. Neocortical cell classes are flexible entities. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:121–134. doi: 10.1038/nrn1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Head C, Gardiner M. Paroxysms of excitement: sodium channel dysfunction in heart and brain. BioEssays. 2003;25:981–993. doi: 10.1002/bies.10338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jentsch TJ, Hubner CA, Fuhrmann JC. Ion channels: function unravelled by dysfunction. Nature Cell Biol. 2004;6:1039–1047. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard C, Anderson A, Becker A, Poolos NP, Beck H, Johnston D. Acquired dendritic channelopathy in temporal lobe epilepsy. Science. 2004;305:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1097065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George AL., Jr Inherited channelopathies associated with epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 2004;4:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7597.2004.42010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graves TD. Ion channels and epilepsy. Q J Med. 2006;99:201–217. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biervert C, Schroeder B, Kubisch C, Propping P, Jentsch TJ, Steinlein OK. A potassium channel mutation in neonatal human epilepsy. Science. 1998;279:403–406. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkovic SF, Mulley JC, Scheffer IE, Petrou S. Human epilepsies: interaction of genetic and acquired factors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George AL., Jr Inherited disorders of voltage-gated sodium channels. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1990–1999. doi: 10.1172/JCI25505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meisler MH, Kearney JA. Sodium channel mutations in epilepsy and other neurological disorders. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2010–2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI25466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohling R. Voltage-gated sodium channels in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1278–1295. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.40501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummins TR, Xia Y, Haddad GG. Functional properties of rat and human neocortical voltage-sensitive sodium currents. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1052–1064. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.3.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hotson JR, Prince DA, Schwartzkroin PA. Anomalous inward rectification in hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1979;42:889–895. doi: 10.1152/jn.1979.42.3.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llinas R, Sugimori M. Electrophysiological properties of in vitro Purkinje cell dendrites in mammalian cerebellar slices. J Physiol (Lond) 1980;305:171–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stafstrom CE, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Negative slope conductance due to a persistent subthreshold sodium current in cat neocortical neurons in vitro. Brain Res. 1982;236:221–226. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stafstrom CE, Schwindt PC, Chubb MC, Crill WE. Properties of persistent sodium conductance and calcium conductance of layer V neurons from cat sensorimotor cortex in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1985;53:153–170. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connors BW, Prince DA. Effects of local anesthetic QX-314 on the membrane properties of hippocampa pyramidal neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1982;200:476–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alzheimer C, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Modal gating of Na+ channels as a mechanism of persistent Na+ current in pyramidal neurons from rat and cat sensorimotor cortex. J Neurosci. 1993;13:660–673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00660.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jahnsen H, Llinas R. Ionic basis for the electro-responsiveness and oscillatory properties of guinea pig thalamic neurons in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1984;349:227–247. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llinas R, Yarom Y. Electrophysiology of mammalian inferior olive neurones in vitro. Different types of voltage dependent ionic conductances. J Physiol. 1981;315:549–567. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan S, Stewart M, Wong RKS. Differences in voltage-dependent sodium currents exhibited by superficial and deep neurons of guinea pig entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1986–1991. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.5.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu N, Enomoto A, Tanaka S, Hsiao CF, Nykamp DQ, Izhikevich E, Chandler SH. Persistent sodium currents in mesencephalic V neurons participate in burst generation and control of membrane excitability. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:2710–2722. doi: 10.1152/jn.00636.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng J, Powers RK, Newkirk G, Yonkers M, Binder MD. Contribution of persistent sodium currents to spike-frequency adaptation in rat hypoglossal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1035–1041. doi: 10.1152/jn.00831.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bevan S, Lindsay RM, Perkins MN, Raff MC. Voltage gated ionic channels in rat cultured astrocytes, reactive astrocytes and an astrocyte-oligodendrocyte progenitor cell. J Physiol (Paris) 1987;82:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue C, Remy S, Su H, Beck H, Yaari Y. Proximal persistent Na+ channels drive spike afterdepolarizations and associated bursting in adult CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9704–9720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1621-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stafstrom CE, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Repetitive firing in layer V neurons from cat neocortex in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1984;52:264–277. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.52.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.French CR, Sah P, Buckett KJ, Gage PW. A voltage-dependent persistent sodium current in mammalian hippocampal neurons. J Gen Physiol. 1990;95:1139–1157. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.6.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crill WE. Persistent sodium current in mammalian central neurons. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;58:349–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Astman N, Gutnick MJ, Fleidervish IA. Persistent sodium current in layer 5 neocortical neurons is primarily generated in the proximal axon. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3465–3473. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4907-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stys PK, Sontheimer H, Ransom BR, Waxman SG. Noninactivating, tetrodotoxin-sensitive Na+ conductance in rat optic nerve axons. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6976–6980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokuno HA, Kocsis JD, Waxman SG. Noninactivating, tetrodotoxin-sensitive Na+ conductance in peripheral axons. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:212–217. doi: 10.1002/mus.10421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vervaeke K, Hu H, Graham LJ, Storm JF. Contrasting effects of the persistent Na+ current on neuronal excitability and spike timing. Neuron. 2006;49:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantegazza M, Yu FH, Powell AJ, Clare JJ, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Molecular determinants for modulation of persistent sodium current by G-protein beta-gamma subunits. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3341–3349. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0104-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cantrell AR, Catterall WA. Neuromodulation of Na+ channels: an unexpected form of cellular plasticity. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:397–407. doi: 10.1038/35077553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aracri P, Colombo E, Mantegazza M, Scalmani P, Curia G, Avanzini G, Franceschetti S. Layer-specific properties of the persistent sodium current in sensorimotor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3460–3468. doi: 10.1152/jn.00588.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleidervish IA, Gutnick MJ. Kinetics of slow inactivation of persistent sodium current in layer V neurons of mouse neocortical slices. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2125–2130. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor CP. Na+ currents that fail to inactivate. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:455–460. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Catterall WA, Golden AL, Waxman SG. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:397–409. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiernan MC, Krishnan AV, Lin CS, Burke D, Berkovic SF. Mutation in the Na+ channel subunit SCN1B produces paradoxical changes in peripheral nerve excitability. Brain. 2005;128(Pt. 8):1841–1846. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheffer I, Berkovic S. Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus: a genetic disorder with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes. Brain. 1997;120:479–490. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallace R, Wang D, Singh R, Scheffer IE, George AL, Jr, Phillips HA, Saar K, Reis A, Johnson EW, Sutherland GR, Berkovic SF, Mulley JC. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel beta1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat Gen. 1998;19:366–370. doi: 10.1038/1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen C, Westenbroek RE, Xu X, Edwards CA, Sorenson DR, Chen Y, McEwen DP, O'Malley HA, Bharucha V, Meadows LS, Knudsen GA, Vilaythong A, Noebels JL, Saunders TL, Scheuer T, Shrager P, Catterall WA, Isom LL. Mice lacking sodium channel beta1 subunits display defects in neuronal excitability, sodium channel expression, and nodal architecture. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4030–4042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4139-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lossin C, Wang DW, Rhodes TH, Vanoye CG, George AL., Jr Molecular basis of an inherited epilepsy. Neuron. 2002;34:877–884. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spampanato J, Escayg A, Meisler MH, Goldin AL. Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus type 2 mutation W1204R alters voltage-dependent gating of Na(v)1.1 sodium channels. Neuroscience. 2003;116:37–48. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00698-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lossin C, Rhodes TH, Desai RR, Vanoye CG, Wang D, Carniciu S, Devinsky O, George AL., Jr Epilepsy-associated dysfunction in the voltage-gated neuronal sodium channel SCN1A. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11289–11295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11289.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barela AJ, Waddy SP, Lickfett JG, Hunter J, Anido A, Helmers SL, Goldin AL, Escayg A. An epilepsy mutation in the sodium channel SCN1A that decreases channel excitability. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2714–2723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2977-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suguwara T, Tsurubuch Y, Agarwala KL, Ito M, Fukuma G, Mazaki-Miyazaki E, Nagafuji H, Noda M, Imoto K, Wada K, Mitsudome A, Kaneko S, Montal M, Nagata K, Hirose S, Yamakawa K. A missense mutation of the Na+ channel alpha II subunit gene NaV1.2 in a patient with febrile and afebrile seizures causes channel dysfunction. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6384–6389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111065098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kearney JA, Plummer NW, Smith MR, Kapur J, Cummins TR, Waxman SG, Goldin AL, Meisler MH. A gain-of-function mutation in the sodium channel gene Scn2a results in seizures and behavioral abnormalities. Neuroscience. 2001;102:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kearney JA, Yang Y, Beyer B, Bergren SK, Claes L, Dejonghe P, Frankel WN. Severe epilepsy resulting from genetic interaction between SCN2A and KCNQ2. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1043–1048. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Claes L, DelFavero J, Ceulemans B, Lagae L, Van Broeckhoven C, DeJonghe P. De novo mutations in the sodium channel gene SCN1A cause severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1327–1332. doi: 10.1086/320609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nabbout R, Gennaro E, DallaBernardina B, Dulac O, Madia F, Bertini E, Capovilla G, Chiron C, Cristofori G, Elia M, Fontana E, Gaggero R, Granata T, Guerrini R, Loi M, LaSelva L, Lispi ML, Matricardi A, Romeo A, Tzolas V, Valseriati D, Veggiotti P, Vigevano F, Vallee L, Dagna Bricarelli F, Bianchi A, Zara F. Spectrum of SCN1A mutations in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Neurology. 2003;60:1961–1967. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000069463.41870.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fujiwara T, Sugawara T, Mazaki-Miyazaki E, Takahashi Y, Fukushima K, Watanabe M, Hara K, Morikawa T, Yagi K, Yamakawa K, Inoue Y. Mutations of sodium channel alpha subunit type 1 (SCN1A) in intractable childhood epilepsies with frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Brain. 2003;126:531–546. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stafstrom CE. SCN1A in GEFS+, SMEI, and ICEGTC: Alphabet soup or emerging genotypic-phenotypic clarity? Epilepsy Curr. 2003;3:219–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1535-7597.2003.03602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rhodes TH, Vanoye CG, Ohmori I, Yamakawa K, George AL., Jr Sodium channel dysfunction in intractable childhood epilepsy with generalized tonic-clonic seizures. J Physiol. 2005;569.2:433–445. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berkovic SF, Heron SE, Giordano L, Marini C, Guerrini R, Kaplan RE, Gambardella A, Steinlein OK, Grinton BE, Dean JT, Bordo L, Hodgson BL, Yamamoto T, Mulley JC, Zara F, Scheffer IE. Benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures: characterization of a new sodium channelopathy. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:550–557. doi: 10.1002/ana.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scalmani P, Rusconi R, Armatura E, Zara F, Avanzini G, Franceschetti S, Mantegazza M. Effects in neocortical neurons of mutations of the Nav1.2 Na+ channel causing benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10100–10109. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2476-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rhodes TH, Lossin C, Vanoye CG, Wang DW, George AL., Jr Noninactivating voltage-gated sodium channels in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11147–11152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402482101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu FH, Mantegazza M, Westenbroek RE, Robbins CA, Kalume F, Burton KA, Spain WJ, McKnight GS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Reduced sodium current in GABAergic interneurons in a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/nn1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Drongelen W, Koch H, Elsen FP, Lee HC, Mrejeru A, Doren E, Marcuccilli CJ, Hereld M, Stevens RL, Ramirez JM. Role of persistent sodium current in bursting activity of mouse neocortical networks in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2564–2577. doi: 10.1152/jn.00446.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamakawa K. Epilepsy and sodium channel gene mutations: gain or loss of function? NeuroReport. 2005;16:1–3. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200501190-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burgess DL. Neonatal epilepsy syndromes and GEFS+: mechanistic considerations. Epilepsia. 2005;46(suppl 10):51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Agrawal N, Alonso A, Ragsdale DS. Increased persistent sodium currents in rat entorhinal cortex layer V neurons in a post-status epilepticus model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1601–1604. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.23103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vreugdenhil M, Hoogland G, van Veelen CW, Wadman WJ. Persistent sodium current in subicular neurons isolated from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2769–2778. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cohen I, Navarro V, Clemenceau S, Baulac M, Miles R. On the origin of interictal activity in human temporal lobe epilepsy in vitro. Science. 2002;298:1418–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.1076510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stafstrom CE. The role of the subiculum in epilepsy and epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Curr. 2005;5:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lucas PT, Meadows LS, Nicholls S, Ragsdale DS. An epilepsy mutation in the β1 subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel results in reduced channel sensitivity to pheytoin. Epilepsy Res. 2005;64:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guerrini R, Dravet C, Genton P, Belmonte A, Kaminska A, Dulac O. Lamotrigine and seizure aggravation in severe myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1998;39:508–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alekov AK, Rahman MM, Mitrovic N, Lehmann-Horn F, Lerche H. Enhanced inactivation and acceleration of activation of the sodium channel associated with epilepsy in man. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:2171–2176. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vanoye CG, Lossin C, Rhodes TH, George AL. Single-channel properties of human Nav1.1 and mechanism of channel dysfunction in SCN1A-associated epilepsy. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:1–14. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chao TI, Alzheimer C. Effects of phenytoin on the persistent Na+ current of mammalian CNS neurones. NeuroReport. 1995;6:1778–1780. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199509000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Segal MM, Douglas AF. Late sodium channel openings underlying epileptiform activity are preferentially diminished by the anticonvulsant phenytoin. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:3021–3034. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lampl I, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Reduction of cortical pyramidal neuron excitability by the action of phenytoin on persistent Na+ current. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1998;284:228–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Niespodziany I, Klitgaard H, Margineanu DG. Is the persistent sodium current a specific target of anti-absence drugs? Neuropharmacology. 2004;15:1049–1052. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200404290-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berger T, Luscher HR. Associative somatodendritic interaction in layer V pyramidal neurons is not affected by the antiepileptic drug lamotrigine. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1688–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taverna S, Mantegazza M, Franceschetti S, Avanzini G. Valproate selectively reduces the persistent fraction of Na+ current in neocortical neurons. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32:304–308. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taverna S, Sancini G, Mantegazza M, Franceschetti S, Avanzini G. Inhibition of transient and persistent Na+ current fractions by the new anticonvulsant topiramate. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1999;288:960–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gebhardt C, Breustedt JM, Noldner M, Chatterjee SS, Heinemann U. The antiepileptic drug losigamone decreases the persistent Na+ current in rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2001;920:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spadoni F, Hainsworth AH, Mercuri NB, Caputi L, Martella G, Lavaroni F, Bernardi G, Stefani A. Lamotrigine derivatives and riluzole inhibit INaP in cortical neurons. NeuroReport. 2002;13:1167–1170. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Urbani A, Belluzzi O. Riluzole inhibits the persistent sodium current in mammalian CNS neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3567–3574. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Martella A, DePersis C, Bonsi P, Natoli S, Cuomo D, Bernardi G, Calabresi P, Pisani A. Inhibition of persistent sodium current fraction and voltage-gated L-type calcium current by propofol in cortical neurons: implications for its antiepileptic activity. Epilepsia. 2005;46:624–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.34904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]