Abstract

Protein O mannosylation is initiated in the endoplasmic reticulum by protein O-mannosyltransferases (Pmt proteins) and plays an important role in the secretion, localization, and function of many proteins, as well as in cell wall integrity and morphogenesis in fungi. Three Pmt proteins, each belonging to one of the three respective Pmt subfamilies, are encoded in the genome of the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Disruption of the C. neoformans PMT4 gene resulted in abnormal growth morphology and defective cell separation. Transmission electron microscopy revealed defective cell wall septum degradation during mother-daughter cell separation in the pmt4 mutant compared to wild-type cells. The pmt4 mutant also demonstrated sensitivity to elevated temperature, sodium dodecyl sulfate, and amphotericin B, suggesting cell wall defects. Further analysis of cell wall protein composition revealed a cell wall proteome defect in the pmt4 mutant, as well as a global decrease in protein mannosylation. Heterologous expression of C. neoformans PMT4 in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae pmt1pmt4 mutant strain functionally complemented the deficient Pmt activity. Furthermore, Pmt4 activity in C. neoformans was required for full virulence in two murine models of disseminated cryptococcal infection. Taken together, these results indicate a central role for Pmt4-mediated protein O mannosylation in growth, cell wall integrity, and virulence of C. neoformans.

Protein O glycosylation is a fundamentally important protein modification in eukaryotes, in which glycosyl residues are covalently attached to secreted proteins. In fungi, O glycosylation is often referred to as O mannosylation. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, protein O mannosylation is essential for cell viability, cell wall formation, cell integrity, morphology, and budding, and the secretion, localization, and function of many proteins (6, 22, 35, 36). In the human fungal pathogen, Candida albicans, O mannosylation is involved in morphogenic transitions and virulence (16, 23). Furthermore, decreased O mannosylation of proteins in these fungi also results in cell wall changes leading to increased sensitivity to certain antifungal compounds and cell wall destabilizing agents (25, 32, 38, 39).

Protein O mannosylation is initiated in the endoplasmic reticulum by protein O-mannosyltransferases (Pmts) that catalyze the transfer of mannose from the sugar donor, dolichol phosphate-mannose, to the hydroxyl groups of serine and threonine residues in the secreted acceptor protein. The Pmt enzymes have been extensively studied in S. cerevisiae, for which seven Pmt proteins have been described previously (37). Recently, five Pmts were described for C. albicans and three for the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (32, 46). Two PMT genes in S. pombe, OMA1 and OMA4, are not essential for viability. However, oma1Δ and oma4Δ mutants exhibit abnormal cell morphology, altered cell wall structure, and partial cell separation defects (46). The third S. pombe PMT gene, OMA2, is an essential gene (46). In addition, each of the two protein O-mannosyltransferases, Pomt1 and Pomt2, are crucial for growth and development in higher eukaryotes such as Drosophila melanogaster and Homo sapiens (1, 12, 14, 41).

The family of Pmts is comprised of three subfamilies, represented in S. cerevisiae by the Pmt1, Pmt2, and Pmt4 proteins, which are grouped according to phylogenetic analysis and conservation within three main sequence motifs (9). In S. cerevisiae, Pmt1 and Pmt2 subfamily members function together as heterodimers, while those of the Pmt4 subfamily form homodimers (5, 8). Likewise, in S. pombe, Pmt1 and Pmt2 subfamily members also function as heterodimers (46). Furthermore, these protein O-mannosyltransferase dimers demonstrate specificity toward protein substrates based on Pmt subfamily (6).

The opportunistic pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans is a ubiquitous, encapsulated yeast that is acquired by a human host through inhalation. In most cases, infection is asymptomatic. However, in individuals with a predisposing immune system deficiency, this organism can disseminate throughout the body with a predilection for the central nervous system, where it can cause a life-threatening meningoencephalitis. In contrast to other human fungal pathogens, C. neoformans is a basidiomycete. In addition, C. neoformans is not a human commensal microorganism but is found primarily in decaying vegetation. Therefore, this yeast must be able to survive equally well in the environment and in the human host. C. neoformans displays unique virulence determinants, such as the formation of a large polysaccharide capsule and the production of melanin (16-18).

In this study, we sought to examine the significance of protein O mannosylation in C. neoformans. Mannosylated proteins are predominant immunogens of this opportunistic fungal pathogen (19). Also, defective protein O mannosylation is known to result in morphological defects in other fungi, and subtle morphological changes have been associated with considerable alterations in fungal survival in vivo (3, 34). Here we have identified three Pmt homologues in C. neoformans and examined the role of one such Pmt homologue, designated Pmt4, in cell integrity, cell separation, and pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains used in this study.

C. neoformans var. grubii MATα strains used in this study were derived from the serotype A strain, H99. F99 is a Ura− derivative of H99 (44). Strains described in this study are the pmt4 mutant GMO1 (pmt4::URA5) and the pmt4 plus PMT4 reconstituted strain GMO3 (pmt4::URA5 PMT4). The S. cerevisiae strain CFY3 (MATa ade2-1 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,112 trp1-Δ901 ura3-52 suc2-Δ9 pmt1::HIS3 pmt4::TRP1) was generously provided by Sabine Strahl at the University of Heidelberg (8).

Oligonucleotide primers and sequencing.

Oligonucleotide primers for PCR and sequencing were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. Sequencing was performed by the Tulane Gene Therapy sequencing facility, the Duke University DNA analysis facility, and Davis Sequencing. Primer sequences used in this study are as follows: GO28, 5′-GTTATTCCACCTATCATCCCAACTCC-3′; GO36, 5′-GCATG TGGTTCTTCATCTTCTACCG-3′; GO34, 5′-AGAGAATATTGAGCGAAGTTGCTCGACC-3′; GO35, 5′-AGAGAATATTCTTGCCTCCAGGAGGTGG-3′; GO44, 5′-GAGGATCCGCAGAAGCATGAGCAGCCTGCGTGGC-3′; GO45, 5′-GCGGATCCGTGCTGAATGCAGCATCAGTTCGCCG-3′; GO49, 5′-GAGAGATATCGCTGCGAGGATGTGAGCTGGAGAGC-3′; GO50, 5′-GAGAGATATCAAGCTTATAGAAGAGATGTAGAAACTAGC-3′; GO58, 5′-TCCCTACGTCGGGATGAGAAGC-3′; GO59, 5′-CCATAGAATGGCCCCTTTTGATG-3′; GO53, 5′-GAGATGGCTGTGCCCAAAAAACGTAACC-3′; GO54, 5′-CTTGGAGAAATTTAATTCTATGTCAAACC-3′; GO74, 5′-TTCTCACATCACATCCGAACATAAACAACCAGAGATGGCTGTGCCCAAAAAACG-3′; GO75, 5′-CTTTTTATTGTCAGTACTGATTAGGGGCAGGTTACTTGGAGAAATTTAATTCTATGTC-3′; GO55, 5′-GATATGGCTCTCGCTCCTCGCAAGAGG-3′; GO56, 5′-CTCATCCATCGAATGCGTCTTCTTGG-3′; GO72, 5′-TTCTCACATCACATCCGAACATAAACAACCAGATATGGCTCTCGCTCCTCG-3′; GO73, 5′-CTTTTTATTGTCAGTACTGATTAGGGGCAGGTTACTCATCCATCGAATGCGTCTTC-3′; FOX47, 5′-GTTATGTCATATCCCAATCC-3′; FOX50, 5′-AATCTGCAGGTCGGGGTAGG-3′; PW371, 5′-CAGTCTAAGCGAGGTATTCTTACCTTGAAGTA-3′; PW372, 5′-GGTGATGACCTGACCGTCAGGAAGCTCGTAAG-3′.

C. neoformans strain construction.

PMT homologs were identified by tblastn searches using S. cerevisiae Pmt1, 2, and 4 protein sequences against The Institue for Genomic Research (www.tigr.org) and H99 genomic databases (H99 sequencing project, Duke IGSP Center for Applied Genomics and Technology; http://cneo.genetics.duke.edu) (21). PMT4 was PCR amplified from the H99 genomic template using primers GO28 and GO36 and cloned into pCR4-TOPO (Invitrogen) to generate pGMO11. The URA5 marker was also PCR amplified using H99 genomic DNA as a template and primers GO34 and GO35, introducing SspI sites at both ends of the fragment. The amplicon was subsequently cloned into pCR4-TOPO to generate pGMO13. For construction of the disruption allele, URA5 was released from pGMO13 by SspI digestion and blunt-end ligated into the EcoRV site of pGMO11. The PMT4::URA5 construct was then PCR amplified to generate a linear disruption allele and gel purified for use in biolistic transformation into F99 as previously described (40).

For reconstitution of the pmt4::URA5 strain, the PMT4 gene, including approximately 1.4 kb of the 5′ untranslated region and the 880-bp 3′ untranslated region was PCR amplified with primers GO44 and GO45 and cloned in pCR4-TOPO to generate pGMO16. The NAT marker for nourseothricin resistance was PCR amplified using pGMC200 template with primers GO49 and GO50 and cloned into pCR4-TOPO. The NAT marker was released by EcoRV digestion and blunt-end ligated into PmeI-digested pGMO16 to generate pGMO18, which was used to transform the pmt4 mutant strain (GMO1) by biolistic transformation to generate strain GMO3. Transformants were screened by PCR to demonstrate the presence of an intact PMT4 gene and confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Southern analysis.

Genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (31). Approximately 10 μg genomic DNA was digested with SacI and HindIII, resolved on a 1% agarose gel, and transferred to a Nytran membrane (Schleicher and Schuell Bioscience). The probe specific for PMT4 exon 3 was PCR amplified with primers GO58 and GO59 and labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) using the DIG-easy labeling kit (Roche). Hybridization was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche), and signals were visualized by autofluorography.

Northern blot analysis.

C. neoformans strain H99 was incubated to mid-log phase in yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium, pelleted, washed, and incubated under the following conditions for 1 h: YPD at 30°C, YPD at 37°C, synthetic complete minus glucose (SC-glucose) at 30°C, and synthetic low-ammonium dextrose at 30°C. C. neoformans strains H99 and GMO1 were incubated to mid-log phase in YPD medium, pelleted, washed, and incubated under the following conditions for 1 h: YPD 30°C, YPD 39°C, YPD 39°C plus 0.5 μg/ml amphotericin B, or YPD 30°C plus 100 μg/ml hygromycin B for 60 min. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and further sample purification was performed using the RNeasy cleanup kit (QIAGEN). Twelve micrograms of total RNA was resolved on a 1.2% agarose gel, transferred to a Nytran membrane, and probed with a 32P-random-labeled probe (All-in-one random prime labeling mix; Sigma) in UltraHyb hybridization buffer (Ambion). The PMT4 probe template was amplified with primers GO58 and GO59. The FKS1 probe template was amplified with primers FOX47 and FOX50, and the ACTIN probe template was amplified with primers PW371 and PW372.

Fluorescence microscopy.

C. neoformans strains were grown in liquid YPD at 30°C for 24 h, pelleted, fixed, and stained with Alexa fluor 488-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; Molecular Probes) as previously described (4). Cells were viewed under fluorescent and phase contrast microscopy using an Olympus BX51 microscope and images captured with MagnaFIRE software version 1.0 (magnification, ×5).

TEM.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed by the Molecular Microbiology Imaging Facility at Washington University in St. Louis. C. neoformans strains were grown in liquid YPD at 30°C to mid-log phase and processed by either KMnO4 fixation, acetone dehydration, and lead citrate staining or fixed with paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde, followed by postfixation in osmium tetroxide and dehydration in ethanol.

Growth characterization of C. neoformans strains.

C. neoformans strains were grown in liquid YPD at 30°C to mid-log phase, counted, and normalized to 2 × 107 CFU/ml. Serial dilutions were spotted onto YPD plus 0.025% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) or prewarmed YPD plates at 30°C, 37°C, or 39°C and incubated for 2 days.

Antifungal susceptibility E-test.

C. neoformans strains H99, GMO1, and GMO3 were grown overnight in YPD at 30°C, pelleted, and washed in sterile nanopure water. Fifty-microliter aliquots containing 5 × 105 CFU were plated on 0.5× YPD plates (25 ml medium in each plate) and allowed to dry before application of amphotericin B E-test strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). Plates were incubated for 3 days at either 30°C or 39°C, and the MICs were determined.

Complementation of S. cerevisiae pmt1pmt4Δ temperature sensitivity.

ScPMT4 was PCR amplified from the wild-type genomic template with primers GO53 and GO54 and cloned into pYES2.1 (Invitrogen) to yield pYES2.1-ScPMT4. ScPMT4 was PCR amplified for gap repair with primers GO74 and GO75. CnPMT4 was PCR amplified from reverse-transcribed mRNA (SuperScriptII reverse transcription kit) using primers GO55 and GO56 and cloned into pYES2.1. CnPMT4 was PCR amplified for gap repair with primers GO72 and GO73. Gap repair was performed as described previously (28) in the S. cerevisiae pmt1pmt4Δ strain CFY3 with KpnI- and SphI-digested pAG36 (generous gift from the McCusker laboratory at Duke University) (10). Transformants were screened for the presence of recombined insert by PCR analysis. To test for complementation of temperature sensitivity, strains were grown to log phase in synthetic complete medium lacking uracil (SC-ura) at 25°C, adjusted to 2 × 107 CFU/ml, and serially diluted, and 5 μl of each dilution was spotted onto YPD and SC-ura plates and incubated for 4 days at 25°C and 35°C, respectively.

Isolation of cell wall proteins.

Surface-associated cell wall proteins were isolated as previously described (30). Briefly, C. neoformans yeast cells were grown in liquid YPD at 37°C to stationary phase and cells were collected by centrifugation. Cells were frozen at −80°C and then resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, Complete protease inhibitor [Roche]). Cells were mechanically lysed with an equal volume of 0.5-mm glass beads in a mini-bead beater (Biospec Products). Cell wall fractions were isolated and washed as described previously (21). Cell surface-associated proteins were then released in SDS extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M EDTA, 2% SDS, 10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) by boiling at 100°C for 10 min and isolated by pelleting at 13,000 rpm for 10 min (accuSpin Micro R; Fisher Scientific). SDS-extracted proteins in the resulting supernatants were frozen at −80°C, lyophilized, and quantified using the BCA protein assay (Pierce).

One-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

Samples containing 50 μg protein were precipitated in 10% trichloroacetic acid in acetone at −20°C to reduce the amount of contaminating polysaccharides, suspended in loading buffer, and run in duplicate on a 10% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). Protein bands were silver stained using the Bio-Rad Silver Stain Plus kit. Glycosylation of proteins was detected by staining with the Pro-Q Emerald 300 glycoprotein gel and blot stain kit (Molecular Probes) and imaging with a Bio-Rad Geldoc imaging system.

Two-dimensional PAGE.

Samples containing approximately 150 μg protein were precipitated in 10% trichloroacetic acid in acetone at −20°C to reduce the amount of contaminating polysaccharides. Samples were suspended in rehydration sample buffer {8 M urea, 2% 3-[(3-cholamidylpropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 50 mM DTT, 0.2% Bio-Lyte 3/10 ampholyte, 0.001% bromphenol blue (Bio-Rad)} and used to passively rehydrate Readystrip immobilized pH gradient (IPG) 11-cm, pH 5 to 8 isoelectric focusing (IEF) strips (Bio-Rad). IEF strips were focused in a PROTEAN IEF cell (Bio-Rad) at 20°C using the following program: 250 V for 15 min, 8,000 V for 2.5 h, 8,000 to 35,000 V, 500 V (hold). After isoelectric focusing, IEF strips were reduced (2% DTT) and alkylated (2.5% iodoacetamide) in SDS-PAGE equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 0.375 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol). The SDS-PAGE run was performed using Criterion XT 10% Bis-Tris precast gels (Bio-Rad) in a Bio-Rad CRITERION cell. Two-dimensional (2-D) gels were silver stained using the Bio-Rad Silver Stain Plus kit or the Blum silver stain method (2). For detection of glycoproteins, 2-D gels were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and stained with the Pro-Q Emerald 300 glycoprotein gel and blot stain kit (Molecular Probes) and imaged with a Bio-Rad Versadoc imaging system.

Intravenous murine model.

Female CBA/J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and used between 7 and 10 weeks of age. Mice were infected intravenously in the lateral tail vein with 5 × 105 cells of C. neoformans strain H99 or GMO1. Moribund animals were sacrificed, and the day of death recorded as the following day. All mice were maintained at the Tulane University Health Sciences Center Vivarium in accordance with the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines.

Inhalational murine model.

Female A/Jcr mice were anesthetized and infected with 1 × 105 CFU C. neoformans strain H99, GMO1, or GMO3 intranasally as previously described (43). Animal survival was determined after inoculation, using predetermined clinical endpoints as surrogate markers for mortality (inability to access food or water, severe neurological symptoms). Mice were maintained at the Research Institute for Children Animal Facility in accordance with the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines.

Histology.

Infected brains, lungs, and spleens from sacrificed animals were formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, and sectioned on a microtome and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or mucicarmine. Tissue processing was performed by the Tulane University School of Medicine Histology Research Services.

Motif analysis, accession numbers, and databases.

ClustalW alignment was performed using MacVector, version 7.2. Accession numbers for each of the protein sequences available at GenBank and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) are as follows: AnPmtA(2), AACD01000088.1; AnPmt4, XM_653971.1; AnPmt1, AACD01000080.1; ScPmt1, NC_001136.7; ScPmt2, NC_001133.6; ScPmt4, NC_001142.6; CaPmt1, AF000232.1; CaPmt2, AACQ01000028.1; CaPmt4, AACQ01000107.1; SpOma1, CAB16577; SpOma2, CAC36926; SpOma4, CAA16916. Deduced amino acid sequences of C. neoformans Pmt proteins 1, 2 and 4 were obtained from http://fungal.genome.duke.edu for C. neoformans var. grubii serotype A strain H99. The C. neoformans PMT4 sequence was submitted to GenBank (see below).

Statistics.

Prism software version 4.0a (Graphpad Software, Inc.) was used to perform a log rank test of statistical significance for the survival experiments.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The C. neoformans PMT4 sequence was submitted to GenBank with the accession number DQ666285.

RESULTS

Identification of C. neoformans PMT genes.

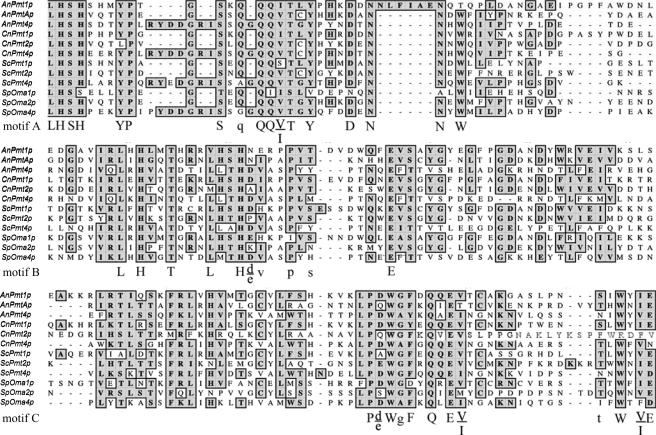

The C. neoformans Pmt gene family members were identified by tblastn searches of the C. neoformans The Institute for Genomic Research, Duke University, and NCBI genome databases using protein sequences of S. cerevisiae Pmt proteins 1, 2, and 4. These bioinformatic searches indicated the presence of only three PMT genes, with two genes residing on chromosome 5 and one gene residing on chromosome 10 in C. neoformans var. grubii. We used ClustalW alignment to compare the deduced amino acid sequences of each of the C. neoformans Pmt proteins with the sequences of Pmt proteins from other fungi including S. cerevisiae, S. pombe, and Aspergillus nidulans (Fig. 1). Alignments demonstrated conservation of the three main Pmt protein sequence motifs (9).

FIG. 1.

Conservation of Pmt sequence motifs in C. neoformans Pmt proteins. Pmt protein sequences are demonstrated from A. nidulans (An), C. neoformans (Cn), S. cerevisiae (Sc), and S. pombe (Sp). Predicted loop 5 of CnPmt4p from position Thr-342 to Asn-511 is aligned to other described or putative fungal Pmt proteins. Conserved residues within motifs A to C (described by Girrbach et al. [9]) are indicated by uppercase (>90%) or lowercase (>50%) symbols.

Each C. neoformans Pmt protein unambiguously segregated into one of the three described Pmt subfamilies, as assessed by conservation of critical residues within conserved protein motifs. Specifically, in the C. neoformans Pmt1 protein encoded on chromosome 5, the tetrapeptide sequence Leu-His-Ser-His is conserved in both motifs A and B, and the Cys residue of motif C is conserved. Pmt2 is encoded on chromosome 10 and lacks the conserved Leu-His-Ser-His and Cys residues in motifs B and C, respectively. The Pmt4 protein contains a seven-amino-acid insertion within motif A, consistent with other proteins in the Pmt4 subfamily. Conversely, the other two C. neoformans Pmt protein sequences lack this seven-amino-acid insertion. We therefore named each putative C. neoformans PMT gene in accordance with its subfamily association: PMT1, PMT2, and PMT4.

In addition to motif analysis, we also performed phylogenetic comparison between the predicted C. neoformans Pmt protein sequences and those of other fungi and higher eukaryotes. This analysis confirmed the predictions of the subfamily sequence comparisons. For example, Pmt4 was most closely related to the other fungal Pmt4 proteins, Pmt1 was most closely related to A. nidulans Pmt1, and Pmt2 was most closely related to A. nidulans Pmt(2)A (G. Olson, unpublished data).

PMT family gene expression.

Northern blot analysis indicated that PMT4 is expressed during growth in liquid YPD at both 30°C and 37°C, as well as during both glucose and nitrogen starvation conditions (Fig. 2A). Although additional Northern analysis revealed that PMT1 and PMT2 are also expressed under these conditions (data not shown), PMT2 was predicted to be essential based on studies of other microorganisms, and we also predicted that Pmt1 and Pmt2 likely function together as a heterodimer. In other fungi, Pmt4 enzymatic activity is important for cell wall formation, cell integrity, and pathogenesis but is not essential for viability (34, 46). Therefore, for initial gene disruption experiments, we chose to study the PMT4 gene to assess the role of Pmt-mediated O mannosylation in C. neoformans growth and pathogenesis.

FIG. 2.

PMT4 gene expression, disruption, and reconstitution in C. neoformans. (A) Northern blot analysis. Wild-type strain H99 was grown to mid-log phase in liquid YPD and shifted for 60 min to the indicated growth conditions. Twelve micrograms of total RNA from each sample was resolved and probed with a 32P-labeled probe specific for exon 3 of PMT4. (B) Southern blot analysis. Ten micrograms of genomic DNA from wild-type (H99), pmt4::URA5 (GMO1), and pmt4 plus PMT4 (GMO3) strains digested with SacI and HindIII, resolved, and probed with a DIG-labeled probe specific for exon 3 of PMT4. (C) Northern blot analysis of FKS1 and PMT4 gene expression in wild-type and pmt4 mutant strains grown as described above and then shifted to the indicated conditions for 60 min. Actin is shown as a loading control.

Disruption of PMT4 by homologous recombination.

To investigate the role of Pmt4 in C. neoformans var. grubii growth and pathogenicity, the PMT4 gene was disrupted by homologous recombination. To ensure that any observed mutant phenotypes were directly attributable to this specific mutation, the pmt4 mutant was reconstituted by the genomic integration of the wild-type PMT4 allele using biolistic transformation to create a pmt4 plus PMT4 reconstituted strain (GMO3). PCR and Southern blot analysis confirmed the genotype of these strains (Fig. 2B). Using the indicated PMT4 sequence as a probe, genomic DNA digested with HindIII and SacI generated an internal control fragment at 1.8 kb and a wild-type 1.3-kb fragment in H99 and GMO3 strains. A 3.1-kb band corresponding to the pmt4::URA5 mutant allele is visible in strains GMO1 (pmt4::URA5) and GMO3. Northern blot analysis using a probe specific for exon 3 demonstrated the absence of the PMT4 transcript in the pmt4 mutant (Fig. 2C) and restoration of the transcript in the pmt4 plus PMT4 reconstituted strain (data not shown). A slightly higher level of PMT4 transcript was detected in the reconstituted strain relative to the wild-type strain, likely due to multiple copies of the reconstitution plasmid or a positional effect.

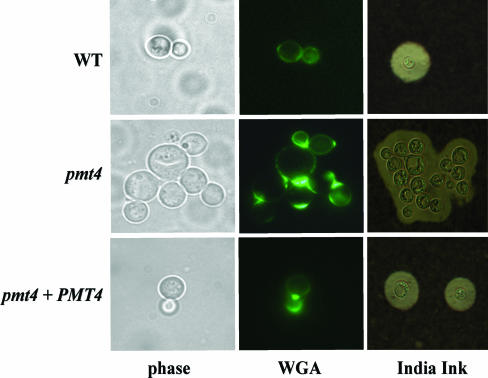

PMT4 is necessary for normal cellular morphology.

Microscopic observation showed that the pmt4 mutant strain grows as small aggregates of yeast cells. In contrast to wild-type cells in which budding was immediately followed by cell separation, the mother and daughter cells of the pmt4 mutant strain failed to dissociate normally. Neither extensive vortexing nor sonication disrupted the cell aggregates. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated WGA staining of fixed and permeabilized pmt4 cells demonstrated the presence of chitin between connected cells, suggesting a partial septation defect (Fig. 3). However, the observation that the pmt4 mutant cells grew well in liquid medium and eventually separated argues against an absolute defect in septation and cell separation. Reintroduction of the wild-type PMT4 gene restored the normal budding and cell separation to the pmt4 mutant (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

PMT4 disruption results in abnormal budding morphology and defective cell separation. (A) Phase-contrast and fluorescent microscopic observation of septum formation and morphology in Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated WGA-stained C. neoformans yeast cells. (B) India ink-stained C. neoformans yeast cells after 4 days of capsule induction in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium. Magnification, ×1,000.

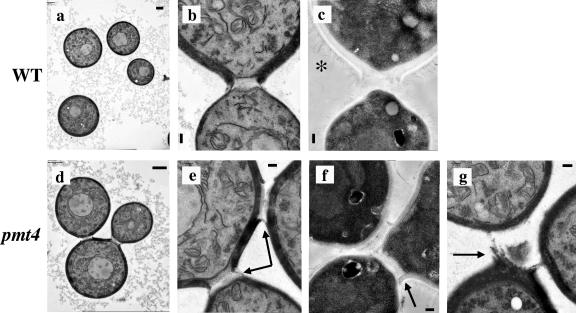

The observation of the chitin connection between the pmt4 mutant cells comprising these small chains led to further investigation of the effect of PMT4 gene disruption on the cell wall, budding, and mother-daughter cell separation by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 4). TEM of wild-type cells showed budding yeast cells that divided and separated normally. In contrast, TEM of the pmt4 mutant cells revealed the presence of small cell aggregates of three cells that appeared to be attached by nondegraded cell wall material (Fig. 4). While phase-contrast microscopy often showed the presence of cell aggregates containing four or more pmt4 mutant cells, it was difficult to observe more than three attached cells by TEM, since these cells tend to be positioned in multiple planes and not in a single section.

FIG. 4.

Transmission electron microscopy of C. neoformans strains H99 (wild-type) and GMO1 (pmt4) that were grown to mid-log phase in liquid YPD at 30°C and prepared by KMnO4 fixation, acetone dehydration, and lead citrate staining (a, b, d, e, and g) or fixed with paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde fixation, osmium tetroxide postfixation, and dehydration in ethanol (c and f). Scale bars, 1 μm (a and b) and 200 nm (c, e, f, and g). Magnification, ×4,337 (a), ×6,506 (d), ×21,686 (b, c, e, and f), and ×17,349 (g). Arrows indicate nondegraded cell wall material. *, capsule fibers extending from the cell wall.

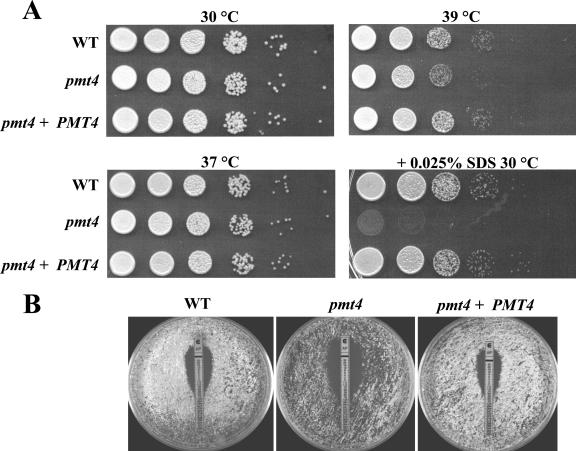

Pmt4 is necessary for cell wall integrity.

In other fungi, O mannosylation of cell wall and cell membrane proteins contributes to cell integrity and cell wall function, especially under conditions of cellular stress (3, 25). To determine the extent to which C. neoformans Pmt4 is important for growth during stressful conditions, the pmt4 mutant was incubated at elevated temperature and in the presence of cell wall-destabilizing agents. The pmt4 mutant growth rate at 30°C and 37°C was the same as that of the wild-type and reconstituted strains (Fig. 5A). However, its growth was slightly reduced at 39°C compared to wild-type and reconstituted strains (Fig. 5A). Also, the addition of 0.025% SDS, which acts to disrupt the cell membrane, severely inhibited growth of the pmt4 mutant at 30°C compared to the wild-type and reconstituted strains. In addition, the MIC of the pmt4 mutant to the membrane ergosterol-binding antifungal amphotericin B at 39°C was decreased to 0.125 μg/ml relative to the wild-type and reconstituted strain MIC of 0.25 μg/ml (Fig. 5B). Reintroduction of the wild-type PMT4 allele complemented all of the pmt4 mutant phenotypes, arguing that these effects are due to the pmt4 mutation. Furthermore, these growth effects of elevated temperature, SDS, and amphotericin B suggest that maintenance of cell wall integrity in the pmt4 mutant strain is compromised.

FIG. 5.

Effect of PMT4 disruption on sensitivity to elevated temperature, SDS, and amphotericin B. (A) C. neoformans strains H99 (wild type), GMO1 (pmt4), and GMO3 (pmt4 plus PMT4) were grown to mid-log phase, normalized to 2 × 107 CFU/ml, serially diluted, and spotted onto YPD medium (or YPD plus 0.025% SDS) and incubated for 2 days at 30°C, 37°C, or 39°C. (B) C. neoformans strains H99 (wild type), GMO1 (pmt4), and GMO3 (pmt4 plus PMT4) (5 × 105 CFU) were plated on 0.5× YPD plates and overlaid with amphotericin (AP) E-test strips for 3 days at 39°C. AP MICs (in μg/ml): H99, 0.25; GMO1, 0.125; GMO3, 0.25.

Compared to its expression at 30°C, the PMT4 gene is transcriptionally repressed at 39°C. However, exposure of the wild-type strain to amphotericin B at this elevated temperature results in relative PMT4 induction (Fig. 2C). To determine a possible mechanism for the observed hypersusceptibility of the pmt4 mutant to amphotericin B, we explored the effect of the pmt4 mutation on other cellular components involved in cell integrity and amphotericin B resistance. The FKS1 gene encodes a target of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Mpk1, and both Fks1 and Mpk1 are involved in the cell integrity pathway (15). Similar to PMT4, FKS1 expression is transcriptionally induced by exposure to amphotericin B at 39°C. However, this induction is absent in a pmt4 mutant, suggesting that Pmt4 is required for the proper transcriptional regulation of factors that favor cell integrity in response to certain stresses, including selected antifungal drug exposure. For example, while the pmt4 strain was increased in sensitivity to amphotericin B, it was not sensitive to the echinocandin caspofungin (data not shown). Decreased Fks1 levels in the pmt4 mutant may account for the increased susceptibility of this strain to amphotericin B due to reduced compensatory action by the cell wall integrity pathway. Interestingly, there appears to be little PMT4 expression during growth in the presence of the aminoglycoside hygromycin B, suggesting that PMT4 may not be generally induced in response to cell stressors.

We also tested the effect of the pmt4 mutation on virulence-associated phenotypes. Melanin production by the pmt4 strain was identical to that of the wild type after 3 days of incubation on either l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) and Niger seed medium (data not shown). Interestingly, India ink staining of the pmt4 strain incubated for four days in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium revealed a large polysaccharide capsule surrounding the clustered mutant cells, whereas wild-type cells typically grow as individual or singly budded yeast cells in this capsule-inducing medium (Fig. 3).

CnPmt4 complements an S. cerevisiae protein O-mannosyltransferase mutant.

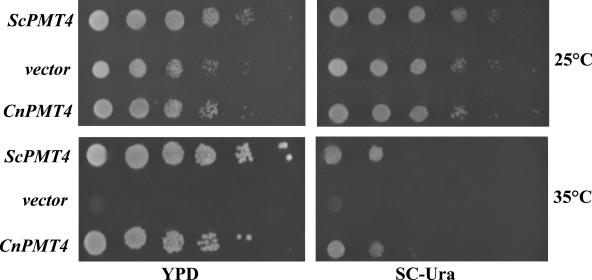

There is currently no in vitro assay available for detecting Pmt4 enzyme activity. Therefore, CnPmt4 activity was confirmed by testing whether it could function as a protein O-mannosyltransferase to complement the temperature sensitivity of the S. cerevisiae pmt1pmt4Δ strain CFY3. To this end, CnPMT4 and ScPMT4 were each expressed in strain CFY3 under the control of the constitutive TEF promoter from Ashbya gossypii. Expression of either CnPMT4 or ScPMT4 restored growth at 35°C to the temperature-sensitive mutant strain (Fig. 6). In contrast, the strain transformed with empty vector was unable to grow at this elevated temperature, suggesting that CnPmt4 functions as a protein O-mannosyltransferase (Fig. 6). These results also suggest that CnPmt4 is orthologous to ScPmt4, and Pmt4-mediated O-mannosyltransferase activity is functionally conserved among these distantly related basidiomycete and ascomycete fungal species.

FIG. 6.

C. neoformans Pmt4 expression complements the temperature sensitivity of the S. cerevisiae pmt1pmt4Δ mutant. S. cerevisiae pmt1pmt4Δ strain CFY3 was transformed with linearized pAG36 plus ScPMT4, uncut pAG36 (vector control), or linearized pAG36 plus CnPMT4 as described in Materials and Methods. Transformants were incubated in SC-ura to exponential phase, normalized to 2 × 107 CFU/ml, serially diluted, spotted onto YPD and selective SC-ura, and incubated for 4 days at 25°C and 35°C.

Proteomic analysis of cell surface-associated proteins.

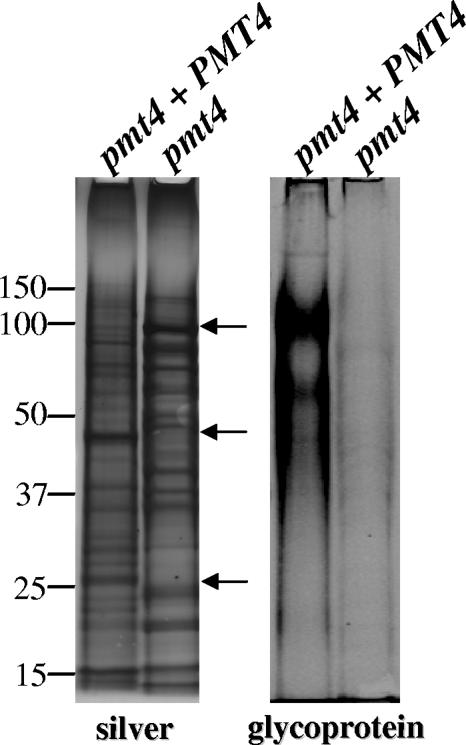

In light of the compromised cell wall integrity of the pmt4 mutant and considering that O mannosylation in other eukaryotes is important for protein function, we hypothesized that Pmt4 loss would negatively affect the cell wall proteome. To examine the influence of Pmt4 activity on cell surface protein composition, proteins were extracted from cell wall fractions isolated from both the pmt4 mutant and reconstituted strains by boiling with SDS under reducing conditions (30). Treatment of purified fungal cell walls in this manner releases proteins associated by noncovalent bonds and disulfide bridges (22). Most cell surface-associated proteins of C. neoformans are isolated in this fraction, unlike other fungi in which covalently associated proteins are abundant (13). Preliminary SDS-PAGE silver stain analysis revealed several molecular weight differences in the protein profile of the equally loaded protein fractions from the pmt4 mutant and reconstituted C. neoformans strains (Fig. 7). Furthermore, fluorescent staining specific for carbohydrates covalently attached to the proteins indicated a noticeable decrease in the overall glycosylation of cell wall proteins from the pmt4 mutant (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

The SDS-extracted cell wall protein fraction from the pmt4 mutant exhibits an altered banding pattern and decreased overall carbohydrate content. Fifty-microgram cell wall protein fractions from C. neoformans strains GMO3 (pmt4 plus PMT4) and GMO1 (pmt4) were trichloroacetic acid precipitated, suspended, and loaded in duplicate onto a 10% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel. (left) Silver stain; (right) glycoprotein stain. Molecular masses are shown in kilodaltons. Arrows indicate prominent differences in banding patterns.

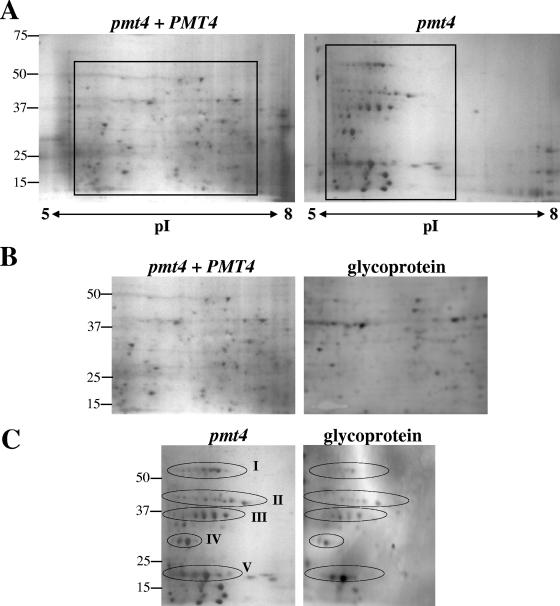

C. neoformans cell wall protein fractions were further analyzed by 2-D gel electrophoresis. The silver-stained 2-D gels revealed a striking difference in the overall proteome of the pmt4 mutant compared to the reconstituted (wild type [WT]) strain (Fig. 8A). The protein spot distribution of the 2-D gel from the pmt4 plus PMT4 strain GMO3 is representative of the pattern normally exhibited by C. neoformans WT strains, with a proteome distribution over a wide range of isoelectric points (pI) and molecular weights (D. Fox, unpublished data). In contrast, several proteins from the pmt4 mutant tended to be organized into discrete horizontal patterns characterized by the same molecular weight but slightly varying pI (Fig. 8C). These proteome patterns are characteristic of multiple glycoisoforms and are grouped into at least five different isoform clusters (Fig. 8A and C) (45). In addition, staining of polyvinylidene difluoride membranes blotted from duplicate 2-D gels for glycoproteins indicated that several proteins are glycosylated in both strains, including those proteins arranged in the pattern characteristic of glycoprotein isoforms in the pmt4 mutant (Fig. 8B and C). These data demonstrate that Pmt4 is necessary for proper mannosylation in C. neoformans and further suggest that Pmt4 may have multiple targets for O-linked mannosylation.

FIG. 8.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis analysis of SDS-extracted cell wall fractions. Protein samples (150 μg) were trichloroacetic acid precipitated and focused on pH 5 to 8 IEF strips and run in the second dimension on 10% Criterion gels. (A) Silver-stained 2-D gels from strains GMO3 (pmt4 plus PMT4) and GMO1 (pmt4). (B) Inset area of the GMO3 (pmt4 plus PMT4) silver-stained 2-D gel and corresponding blot stained for glycosylated proteins. (C) Inset area of the GMO1 (pmt4) silver-stained 2-D gel and corresponding blot stained for glycosylated proteins. Molecular masses are shown in kilodaltons.

PMT4 is required for full virulence in vivo.

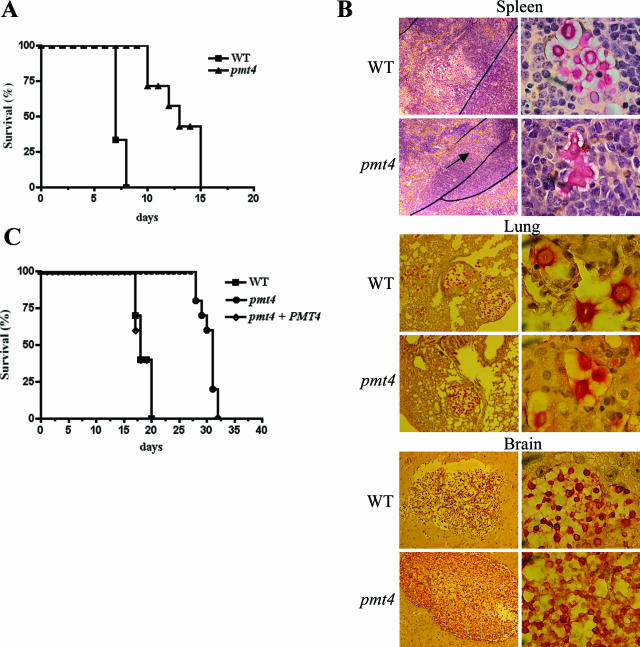

To determine whether Pmt4-mediated protein O mannosylation is important for pathogenesis of C. neoformans, the virulence of the pmt4 mutant was tested in two murine models of C. neoformans disease. During preparation of the C. neoformans inoculum, the multiply budded phenotype of the pmt4 mutant presented a challenge in terms of the most accurate way to enumerate CFU. During the preliminary intravenous challenge experiment, CFUs of each strain were calculated based on individual cells enumerated during the hemacytometer count, regardless of whether the individual cells were unattached or conjoined. However, for the inhalation experiment, a more conservative approach was used while performing hemacytometer counts in which each unattached cell or aggregate of cells was counted as 1 CFU, since comparison of CFUs from plated inoculum counted by the former and latter methods indicated that counting one group of conjoined cells as 1 CFU corresponded most closely with the original hemacytometer count.

In the first experiment, the WT and pmt4 mutant strains were intravenously injected into CBA/J mice, resulting in a hematogenously disseminated infection. Animal survival was assessed over 15 days. The virulence of the pmt4 mutant was significantly attenuated relative to the wild-type strain (P < 0.0002) (Fig. 9A). Given the aberrant morphology of the pmt4 mutant in vitro, histological analysis of brain, lung, and spleen tissue sections from infected mice was performed. Spleen tissue sections revealed a striking difference between animals infected with the wild-type and pmt4 mutant strains. The spleens of mice infected with wild-type C. neoformans contained numerous encapsulated organisms. In contrast, the few organisms observed in the spleens of the mice infected by the pmt4 mutant strain exhibited a branched chain pattern indicative of a separation defect, similar to the growth phenotype observed in vitro (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, the pmt4 mutant yeast cells observed in the brain and lung tissues were morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type cells (Fig. 9B).

FIG. 9.

Pmt4 is required for full C. neoformans virulence. (A) CBA/J mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 cells C. neoformans strains H99 (wild type) (n = 6) or GMO1 (pmt4 mutant) (n = 7), and the infected animals were monitored for survival. (B) Mucicarmine-stained spleen, lung, and brain tissue from intravenously infected mice. Arrow indicates C. neoformans pmt4 mutant cells in the spleen. Magnification, ×100 (left) and ×1,000 (right). (C) Ten A/Jcr mice were inoculated intranasally with 1 × 105 CFU C. neoformans strains H99, GMO1 (pmt4), and GMO3 (pmt4 plus PMT4) and monitored for survival.

To further confirm the role of the Pmt4 protein in C. neoformans pathogenesis, we used a murine inhalation model of cryptococcosis to assess a different route of inoculation and systemic dissemination. Complement C5-deficient A/Jcr mice were intranasally inoculated with 1 × 105 CFU C. neoformans. Using this method of infection, mice inoculated with wild-type C. neoformans experience a reproducible lethal effect in approximately 3 weeks. Mice infected with either the wild-type (H99) or pmt4 plus PMT4 reconstituted strains (GMO3) died from their infection by day 20, with almost identical survival curves (Fig. 9C). In contrast, animals infected with the pmt4 mutant (GMO1) displayed a significantly prolonged survival compared to wild-type or reconstituted strains (H99 versus GMO1, P < 0.0001). Therefore, Pmt4 protein O-mannosyltransferase activity is involved in normal cell separation in vitro and in C. neoformans pathogenesis in two animal models of disease.

DISCUSSION

Protein O mannosylation is an important cellular process in fungi and higher eukaryotes. In this study, we began to investigate the previously uncharacterized significance of protein O mannosylation in the human fungal pathogen C. neoformans by studying the functional role of Pmt4.

Growth of the pmt4 mutant was inhibited at elevated temperature (39°C) and markedly reduced in the presence of 0.025% SDS. Furthermore, the pmt4 mutant was twice as sensitive to amphotericin B as the wild-type and reconstituted strain controls. Recently, it was demonstrated that the growth of mutants in several components of the PKC1 signaling cell integrity pathway is also inhibited at 39°C and in the presence of SDS (7). Additionally, growth of a C. albicans mnt1mnt2Δ strain defective in protein O-mannosyl glycan elongation was severely inhibited in the presence of 0.025% SDS (25). Taken together, these results suggest that the covalent attachment of O-glycans to secreted or cellular proteins in C. neoformans is critical for maintaining cell wall strength and integrity.

Numerous cell wall and cell membrane proteins are O mannosylated in other fungi, thereby contributing to cell surface integrity. Mannosyltransferase function may therefore have a widespread effect on protein targets. For example, in C. albicans, the Kre9 and Pir2 proteins are targets of Pmt1 activity and the Axl2 protein is a target of Pmt4 activity (32). Furthermore, C. albicans, pmt1 and pmt4 homozygous mutants underglycosylate the Sec20 protein, a crucial component of the secretory machinery, and therefore exhibit a significant decrease in cell wall mannoprotein content relative to wild-type cells (32).

The Wsc proteins and Mid2 protein are plasma membrane sensors upstream of the protein kinase C-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway involved in the maintenance of cell wall integrity in S. cerevisiae (11, 42). Lommel et al. reported that WSC protein family members and Mid2 are abnormally cleaved in S. cerevisiae pmt mutants and that Pmt2- and Pmt4-mediated O mannosylation stabilizes and promotes the correct processing of Wsc1, Wsc2, and Mid2 (22) Furthermore, S. cerevisiae strains demonstrated increased osmotic sensitivity when multiple PMT genes were mutated (6). Disruption of the PMTA gene in A. nidulans indicated that Pmt activity is important for cell wall formation, as the pmtA mutant exhibited a decrease in cell wall rigidity and an abnormal morphology (27).

In light of these observations, it is conceivable that loss of Pmt4 also significantly impacts protein function in C. neoformans. Indeed, proteomic analysis of cell surface-associated proteins from the C. neoformans pmt4 strain revealed dramatic differences in global protein glycosylation and proteome distribution compared to the reconstituted strain. Several of the proteins present in the horizontal spot patterns resemble multiple glycoisoforms, which can be indicative of defective glycosylation (45, 47). These glycoisoforms observed in the pmt4 strain may represent Pmt4 targets. Ongoing studies will lead to the identification of such potential Pmt4 targets as well as the corresponding glycosylation modifications.

It is possible that, in the absence of Pmt4-initiated O-glycan biosynthesis, compensatory mechanisms may enable limited protein glycosylation to sustain viability. For example, the proteome pattern resembling multiple glycoforms suggests that Pmt1 and Pmt2 may attempt to compensate for Pmt4 loss, thus generating multiple glycosylation states of certain proteins. The qualitative decrease in the number of visible protein spots in the pmt4 2-D gel could be due to defective protein secretion, since O-glycans can act as a sorting signal for cell surface delivery of proteins (33). Also, certain protein motifs without Pmt4-mediated glycosylation may be improperly processed and more susceptible to proteases (35). The results of proteomic analysis, taken together with observations in other fungi, suggest a compromise of protein secretion and function in the C. neoformans pmt4 strain to which cell wall and cell membrane defects may be attributed.

In the pathogenic fungus C. albicans, Pmt4 is required for full virulence. pmt4/pmt4 homozygous mutants are significantly attenuated in mouse models of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis (34). In our studies, we used two murine models of cryptococcal disease, intravenous and inhalation, to examine the role of Pmt4 in C. neoformans pathogenesis. Disruption of the PMT4 gene in C. neoformans resulted in attenuation of virulence in both models of cryptococcal disease, suggesting an important role for O mannosylation in C. neoformans pathogenesis. Furthermore, reintroduction of the wild-type PMT4 fully restored virulence to that of the wild-type strain. It is likely that the attenuation in the pmt4 mutant is attributable at least in part to basic cellular events such as the aberrant budding pattern, defective cell separation, and altered cell integrity that result from a loss of Pmt4-mediated protein O mannosylation within the cell. It is conceivable that the cell separation defect of the pmt4 mutant affected dissemination or physiological clearance mechanisms within the host. Li et al. recently described a “sugar-induced,” protein-mediated cell flocculation phenotype in a C. neoformans serotype D strain in which “clump+” cells more readily adhered to macrophage-like J774 cells and were more efficiently taken up by complement-mediated phagocytosis (20). Survival of mice infected with “clump+” cells was significantly increased relative to those infected with “clump−” cells (20). In addition, decreased O mannosylation of secreted proteins may also influence the immunological aspect of pathogenesis, such as the induction of T-cell responses (23, 24, 26, 29).

Intriguingly, the morphological phenotype of the pmt4 mutant in the spleen was different from that observed in the brain and lungs, where the pmt4 mutant cells were indistinguishable from wild-type cells (Fig. 9B). These differences observed in the morphology of the pmt4 strain in the lungs and brain compared to the spleen are possibly attributable to differences in growth, since the mutant cells eventually separate as the population of cells age and approach stationary phase in liquid culture. We hypothesize that growth conditions present in the lung and brain tissues are more favorable for C. neoformans growth than in the spleen, which is a lymphatic tissue normally abundant in lymphocytes and macrophages. It is also possible that host-specific factors in the brain and lung tissues compensate for the delayed cell separation and reduced cell wall integrity of the pmt4 strain.

The results described herein suggest that Pmt4 activity, or loss thereof, affects several protein targets. While a basal level of glycosylation is likely required for cell viability, identification of specific protein targets that are O mannosylated by Pmt4 is important for defining the mechanisms by which protein O mannosylation contributes to cellular events central to C. neoformans growth and pathogenesis. These results collectively indicate a multifaceted role for Pmt4-mediated protein O mannosylation in the cell budding morphology, cell separation, cell surface integrity and pathogenesis of C. neoformans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill Thompson, Richard Kleinschmidt, and all the members of the Alspaugh laboratory for technical assistance and helpful discussions. We also thank Darcy Gill for performing TEM and Aki Yoneda in the Doering laboratory for helpful discussions regarding TEM.

This work was supported in part by an ASM Katrina Grant-in-Aid Award (G.M.O.), a Burroughs Wellcome Fund New Investigator Award in Molecular Pathogenic Mycology (K.L.B. and J.A.A.), a grant from the Board of Regents of the State of Louisiana (K.L.B.), and a grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation of Los Angeles. This work was also supported by NIH grants AI050128 (J.A.A.), AI055302 (D.S.F.), and AI054958 (P.W.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beltran-Valero de Bernabe, D., S. Currier, A. Steinbrecher, J. Celli, E. van Beusekom, B. van der Zwaag, H. Kayserili, L. Merlini, D. Chitayat, W. B. Dobyns, B. Cormand, A. E. Lehesjoki, J. Cruces, T. Voit, C. A. Walsh, H. van Bokhoven, and H. G. Brunner. 2002. Mutations in the O-mannosyltransferase gene POMT1 give rise to the severe neuronal migration disorder Walker-Warburg syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71:1033-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum, H., H. Beier, and H. J. Gross. 1987. Improved silver staining of plant proteins, RNA and DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis 8:93-99. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ernst, J. F., and S. K. Prill. 2001. O-glycosylation. Med. Mycol. 39(Suppl. 1):67-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox, D. S., G. M. Cox, and J. Heitman. 2003. Phospholipid-binding protein Cts1 controls septation and functions coordinately with calcineurin in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1025-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gentzsch, M., T. Immervoll, and W. Tanner. 1995. Protein O-glycosylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the protein O-mannosyltransferases Pmt1p and Pmt2p function as heterodimer. FEBS Lett. 377:128-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentzsch, M., and W. Tanner. 1996. The PMT gene family: protein O-glycosylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is vital. EMBO J. 15:5752-5759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerik, K. J., M. J. Donlin, C. E. Soto, A. M. Banks, I. R. Banks, M. A. Maligie, C. P. Selitrennikoff, and J. K. Lodge. 2005. Cell wall integrity is dependent on the PKC1 signal transduction pathway in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 58:393-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girrbach, V., and S. Strahl. 2003. Members of the evolutionarily conserved PMT family of protein O-mannosyltransferases form distinct protein complexes among themselves. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12554-12562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girrbach, V., T. Zeller, M. Priesmeier, and S. Strahl-Bolsinger. 2000. Structure-function analysis of the dolichyl phosphate-mannose: protein O-mannosyltransferase ScPmt1p. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19288-19296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker. 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15:1541-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray, J. V., J. P. Ogas, Y. Kamada, M. Stone, D. E. Levin, and I. Herskowitz. 1997. A role for the Pkc1 MAP kinase pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in bud emergence and identification of a putative upstream regulator. EMBO J. 16:4924-4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichimiya, T., H. Manya, Y. Ohmae, H. Yoshida, K. Takahashi, R. Ueda, T. Endo, and S. Nishihara. 2004. The twisted abdomen phenotype of Drosophila POMT1 and POMT2 mutants coincides with their heterophilic protein O-mannosyltransferase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279:42638-42647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James, P. G., R. Cherniak, R. G. Jones, C. A. Stortz, and E. Reiss. 1990. Cell-wall glucans of Cryptococcus neoformans Cap 67. Carbohydr. Res. 198:23-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, D. S., Y. K. Hayashi, H. Matsumoto, M. Ogawa, S. Noguchi, N. Murakami, R. Sakuta, M. Mochizuki, D. E. Michele, K. P. Campbell, I. Nonaka, and I. Nishino. 2004. POMT1 mutation results in defective glycosylation and loss of laminin-binding activity in alpha-DG. Neurology 62:1009-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraus, P. R., D. S. Fox, G. M. Cox, and J. Heitman. 2003. The Cryptococcus neoformans MAP kinase Mpk1 regulates cell integrity in response to antifungal drugs and loss of calcineurin function. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1377-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon-Chung, K. J. 1994. Phylogenetic spectrum of fungi that are pathogenic to humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19(Suppl. 1):S1-S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon-Chung, K. J., I. Polacheck, and T. J. Popkin. 1982. Melanin-lacking mutants of Cryptococcus neoformans and their virulence for mice. J. Bacteriol. 150:1414-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and J. C. Rhodes. 1986. Encapsulation and melanin formation as indicators of virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 51:218-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levitz, S. M., S. Nong, M. K. Mansour, C. Huang, and C. A. Specht. 2001. Molecular characterization of a mannoprotein with homology to chitin deacetylases that stimulates T cell responses to Cryptococcus neoformans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10422-10427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, L., O. Zaragoza, A. Casadevall, and B. C. Fries. 2006. Characterization of a flocculation-like phenotype in Cryptococcus neoformans and its effects on pathogenesis. Cell. Microbiol. 8:1730-1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loftus, B. J., E. Fung, P. Roncaglia, D. Rowley, P. Amedeo, D. Bruno, J. Vamathevan, M. Miranda, I. J. Anderson, J. A. Fraser, J. E. Allen, I. E. Bosdet, M. R. Brent, R. Chiu, T. L. Doering, M. J. Donlin, C. A. D'Souza, D. S. Fox, V. Grinberg, J. Fu, M. Fukushima, B. J. Haas, J. C. Huang, G. Janbon, S. J. Jones, H. L. Koo, M. I. Krzywinski, J. K. Kwon-Chung, K. B. Lengeler, R. Maiti, M. A. Marra, R. E. Marra, C. A. Mathewson, T. G. Mitchell, M. Pertea, F. R. Riggs, S. L. Salzberg, J. E. Schein, A. Shvartsbeyn, H. Shin, M. Shumway, C. A. Specht, B. B. Suh, A. Tenney, T. R. Utterback, B. L. Wickes, J. R. Wortman, N. H. Wye, J. W. Kronstad, J. K. Lodge, J. Heitman, R. W. Davis, C. M. Fraser, and R. W. Hyman. 2005. The genome of the basidiomycetous yeast and human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Science 307:1321-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lommel, M., M. Bagnat, and S. Strahl. 2004. Aberrant processing of the WSC family and Mid2p cell surface sensors results in cell death of Saccharomyces cerevisiae O-mannosylation mutants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:46-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansour, M. K., L. S. Schlesinger, and S. M. Levitz. 2002. Optimal T cell responses to Cryptococcus neoformans mannoprotein are dependent on recognition of conjugated carbohydrates by mannose receptors. J. Immunol. 168:2872-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monari, C., E. Pericolini, G. Bistoni, A. Casadevall, T. R. Kozel, and A. Vecchiarelli. 2005. Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan induces expression of fas ligand in macrophages. J. Immunol. 174:3461-3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munro, C. A., S. Bates, E. T. Buurman, H. B. Hughes, D. M. Maccallum, G. Bertram, A. Atrih, M. A. Ferguson, J. M. Bain, A. Brand, S. Hamilton, C. Westwater, L. M. Thomson, A. J. Brown, F. C. Odds, and N. A. Gow. 2005. Mnt1p and Mnt2p of Candida albicans are partially redundant alpha-1,2-mannosyltransferases that participate in O-linked mannosylation and are required for adhesion and virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 280:1051-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy, J. W. 1988. Influence of cryptococcal antigens on cell-mediated immunity. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10(Suppl. 2):S432-S435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oka, T., T. Hamaguchi, Y. Sameshima, M. Goto, and K. Furukawa. 2004. Molecular characterization of protein O-mannosyltransferase and its involvement in cell-wall synthesis in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiology 150:1973-1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oldenburg, K. R., K. T. Vo, S. Michaelis, and C. Paddon. 1997. Recombination-mediated PCR-directed plasmid construction in vivo in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:451-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pietrella, D., C. Corbucci, S. Perito, G. Bistoni, and A. Vecchiarelli. 2005. Mannoproteins from Cryptococcus neoformans promote dendritic cell maturation and activation. Infect. Immun. 73:820-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitarch, A., M. Sanchez, C. Nombela, and C. Gil. 2002. Sequential fractionation and two-dimensional gel analysis unravels the complexity of the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans cell wall proteome. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1:967-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitkin, J. W., D. G. Panaccione, and J. D. Walton. 1996. A putative cyclic peptide efflux pump encoded by the TOXA gene of the plant-pathogenic fungus Cochliobolus carbonum. Microbiology 142(Pt 6):1557-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prill, S. K., B. Klinkert, C. Timpel, C. A. Gale, K. Schroppel, and J. F. Ernst. 2005. PMT family of Candida albicans: five protein mannosyltransferase isoforms affect growth, morphogenesis and antifungal resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 55:546-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Proszynski, T. J., K. Simons, and M. Bagnat. 2004. O-glycosylation as a sorting determinant for cell surface delivery in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1533-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rouabhia, M., M. Schaller, C. Corbucci, A. Vecchiarelli, S. K. Prill, L. Giasson, and J. F. Ernst. 2005. Virulence of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans requires the five isoforms of protein mannosyltransferases. Infect. Immun. 73:4571-4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders, S. L., M. Gentzsch, W. Tanner, and I. Herskowitz. 1999. O-Glycosylation of Axl2/Bud10p by Pmt4p is required for its stability, localization, and function in daughter cells. J. Cell Biol. 145:1177-1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strahl-Bolsinger, S., M. Gentzsch, and W. Tanner. 1999. Protein O-mannosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1426:297-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strahl-Bolsinger, S., and W. Tanner. 1991. Protein O-glycosylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification and characterization of the dolichyl-phosphate-D-mannose-protein O-D-mannosyltransferase. Eur. J. Biochem. 196:185-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timpel, C., S. Strahl-Bolsinger, K. Ziegelbauer, and J. F. Ernst. 1998. Multiple functions of Pmt1p-mediated protein O-mannosylation in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 273:20837-20846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timpel, C., S. Zink, S. Strahl-Bolsinger, K. Schroppel, and J. Ernst. 2000. Morphogenesis, adhesive properties, and antifungal resistance depend on the Pmt6 protein mannosyltransferase in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 182:3063-3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toffaletti, D. L., T. H. Rude, S. A. Johnston, D. T. Durack, and J. R. Perfect. 1993. Gene transfer in Cryptococcus neoformans by use of biolistic delivery of DNA. J. Bacteriol. 175:1405-1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.van Reeuwijk, J., M. Janssen, C. van den Elzen, D. Beltran-Valero de Bernabe, P. Sabatelli, L. Merlini, M. Boon, H. Scheffer, M. Brockington, F. Muntoni, M. Huynen, A. Verrips, C. Walsh, P. Barth, H. Brunner, and H. van Bokhoven. 2005. POMT2 mutations cause alpha-dystroglycan hypoglycosylation and Walker Warburg syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 42:907-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verna, J., A. Lodder, K. Lee, A. Vagts, and R. Ballester. 1997. A family of genes required for maintenance of cell wall integrity and for the stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13804-13809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, P., J. Cutler, J. King, and D. Palmer. 2004. Mutation of the regulator of G protein signaling Crg1 increases virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1028-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, P., J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2000. The G-protein beta subunit GPB1 is required for mating and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:352-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, Y., A. Xu, C. Knight, L. Y. Xu, and G. J. Cooper. 2002. Hydroxylation and glycosylation of the four conserved lysine residues in the collagenous domain of adiponectin. Potential role in the modulation of its insulin-sensitizing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277:19521-19529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willer, T., M. Brandl, M. Sipiczki, and S. Strahl. 2005. Protein O-mannosylation is crucial for cell wall integrity, septation and viability in fission yeast. Mol. Microbiol. 57:156-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wopereis, S., S. Grunewald, E. Morava, J. M. Penzien, P. Briones, M. T. Garcia-Silva, P. N. Demacker, K. M. Huijben, and R. A. Wevers. 2003. Apolipoprotein C-III isofocusing in the diagnosis of genetic defects in O-glycan biosynthesis. Clin. Chem. 49:1839-1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]