Abstract

There are five known subtypes of muscarinic receptors (M1–M5). We have used knockout mice lacking the M1, M2, or M4 receptors to determine which subtypes mediate modulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in mouse sympathetic neurons. Muscarinic agonists modulate N- and L-type Ca2+ channels in these neurons through two distinct G-protein-mediated mechanisms. One pathway is fast and membrane-delimited and inhibits N- and P/Q-type channels by shifting their activation to more depolarized potentials. The other is slow and voltage-independent and uses a diffusible cytoplasmic messenger to inhibit both Ca2+ channel types. Using patch-clamp methods on acutely dissociated sympathetic neurons, we isolated each pathway by pharmacological and kinetic means and found that each one is nearly absent in a particular knockout mouse. The fast and voltage-dependent pathway is lacking in the M2 receptor knockout mice; the slow and voltage-independent pathway is absent from the M1 receptor knockout mice; and neither pathway is affected in the M4 receptor knockout mice. The knockout effects are clean and are apparently not accompanied by compensatory changes in other muscarinic receptors.

Neuronal function is widely regulated by G-protein-mediated pathways in both the peripheral and central nervous systems. As these pathways often involve families of quite closely related signaling proteins, it has been challenging to determine which molecular species are involved in each physiological response. There are five known subtypes of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChR) (M1–M5), but we lack the specific agonists and antagonists required to distinguish them with sufficient certainty. Many laboratories report that the “even-numbered” M2 and M4 subtypes couple to pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive G proteins, whereas the “odd-numbered” M1, M3, and M5 subtypes couple to PTX-insensitive ones such as Gq/11 (1). Motivated by the imprecision of the current pharmacology, we studied mice lacking specific mAChR genes (knockout or KO mice) to distinguish the physiological roles of several mAChR subtypes in sympathetic neurons.

Since release of neurotransmitter at nerve terminals is driven by influx of Ca2+ through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, modulation of these channels regulates synaptic transmission and neuronal excitability in general (2–4). One well-studied modulatory mechanism uses several classes of G proteins. It is fast and membrane delimited and inhibits N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels by shifting their gating to more depolarized potentials (5–7). It is mediated by the direct binding of G protein βγ dimers to the Ca2+ channel (8, 9). We call this mechanism the “fast” pathway. Another pathway uses PTX-insensitive G proteins of the Gq/11 family (10, 11). It is voltage-independent and modulates N- and L-type channels through a diffusible cytoplasmic second messenger yet to be identified (12–14). As this second pathway is an order of magnitude slower than the fast pathway (15), we call it the “slow” pathway. This pathway also mediates inhibition of a ubiquitous neuronal K+ channel that is responsible for the M-current (12, 16–19).

Rat superior cervical ganglion (SCG) neurons make mRNA for the M1, M2, and M4 mAChR subtypes (20) and express N- and L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (21–23). In these cells, muscarinic agonists induce both the fast modulation of N-type channels (12–14, 24, 25) and the slow modulation of N- and L-type channels (13, 26). Pharmacological evidence suggests that, in the rat, the PTX-insensitive slow pathway is mediated by M1 receptors, and the PTX-sensitive fast pathway, by M4 receptors (25, 27). We have turned to the KO mouse to further probe the molecular identity of receptors mediating these pathways. We find that in the mouse, the slow and PTX-insensitive pathway is mediated only by M1 receptors, and the fast and PTX-sensitive pathway, only by M2 receptors.

METHODS

Mouse Strains and Cell Preparation.

The KO mice were F2 hybrids from crosses of the following strains: M1, 129SvJ × C57BL/6 (28); M2, 129J1 × CF-1 (29); and M4, 129SvEv × CF-1 (30). The control mice were wild-type hybrids from 129SvJ × C57BL/6 crosses for the M1 experiments and from 129SvEv × CF-1 crosses for the M2 and M4 experiments. Mice were anesthetized with CO2 and decapitated at the following ages: M1, 60–100 days; M2 and M4, 28–50 days. Neurons were prepared acutely from the SCG after the ganglia were dissociated in modified Hanks’ solution, using methods of Bernheim et al. (14), slightly modified by Hamilton et al. (28).

Solutions and Materials. Modified Hanks’ dissociation solution contained (mM): 137 NaCl, 0.34 Na2HPO4, 5.4 KCl, 0.44 KH2PO4, 5 glucose, and 5 Hepes, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. For dissociation medium, 10% fetal calf serum was added to DMEM (GIBCO). The external Ringer’s solution used to record ICa contained (mM): 160 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, and 8 glucose, with 500 nM tetrodotoxin, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The standard pipette solution was (mM): 175 CsCl, 5 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, and 0.1 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA). In addition, Na2ATP (3 mM), NaGTP (0.1 mM), and leupeptin (80 μM) were added, and the final pH was titrated to 7.4 with CsOH. In one set of experiments, the BAPTA concentration was raised to 20 mM, and the CsCl concentration was reduced accordingly.

Reagents were obtained as follows: somatostatin (Peninsula); oxotremorine methiodide (oxo-M) and nifedipine (RBI, Natick, MA); ω-conotoxin (ω-CTX) GVIA (Bachem); ω-CTX MVIIC (Neurex, Menlo Park, CA); FPL 64176 was a gift from the laboratory of W. A. Catterall (Univ. of Washington School of Medicine); BAPTA (Molecular Probes); ATP and GTP (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology); papain (Worthington); Dispase (grade 2) (Boehringer Mannheim), leupeptin, DMEM, and fetal bovine serum (GIBCO); and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), collagenase (type 1) (Sigma). The m1 mamba toxin was a kind gift of Lincoln Potter (University of Miami). NEM was prepared as a stock solution in water at 50 mM and stored at −20°C. FPL 64176 was prepared as a stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide at 10 mM. The solutions containing the Ca2+ channel blockers also contained 0.1 mg/ml cytochrome c to prevent nonspecific binding of peptides to the perfusion tubing.

Current Recording. The whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique was used to voltage clamp and dialyze cells at room temperature (22–25°C). Electrodes were pulled from glass hematocrit tubes (VWR Scientific) and fire-polished and had resistances of 1–3 MΩ when measured in Ringer’s solution and filled with internal solution. Membrane current was measured under whole-cell clamp with pipette and membrane capacitance cancellation, sampled at 200 μs and filtered at 2 kHz. The whole-cell access resistance was 3–10 MΩ. Junction potentials have been corrected by −2 mV. Cells were placed in a 100-μl chamber through which solution flowed at 1–2 ml/min. Inflow to the chamber was by gravity from several reservoirs, selectable by activation of solenoid valves. Bath solution exchange was complete by <20 s. In the experiments of Fig. 4 we achieved a faster solution exchange around the cell by raising the cell to the mouth of the inflow tube. Whole-cell capacitance was 15–50 pF.

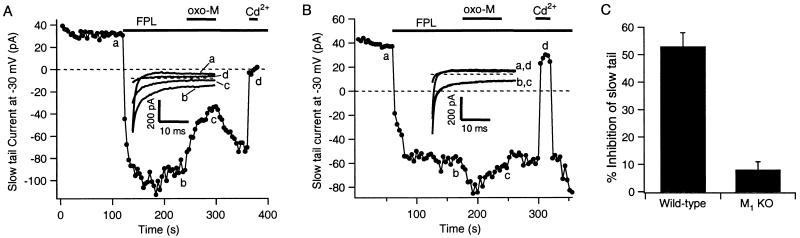

Figure 4.

The fast muscarinic pathway is mediated by M2 receptors. (A–C) Plotted are amplitudes of ICa, elicited by using the double-pulse protocol described in text, for the first pulse (●) and the second pulse (■) in a cell from a wild-type mouse (A), an M4 KO mouse (B), or an M2 KO mouse (C). oxo-M (10 μM) and somatostatin (SS, 250 nM) were bath-applied during the period shown by the bars. Pulses were applied every 4 s (A), 3 s (B), and 4 s (C). For each data point, the “facilitation ratio” was calculated as the ratio of the amplitudes of ICa, P2/P1, from the two pulses. Current traces at the indicated times are shown in the Insets. The time between pulses has been blanked out. (D) For all the experiments from the three mouse strains, the facilitation ratio was calculated for each pulse, and the data were aligned to the time of oxo-M application. The mean facilitation ratio (±SEM) for each pulse is plotted relative to time of oxo-M application.

The amplitude of the peak whole-cell Ca2+ current near 0 mV was defined as the inward current sensitive to block by 100 μM Cd2+. In experiments where control and test conditions were compared, conditions were always alternated cell-to-cell to avoid systematic bias. For the assignment of Ca2+ channel subtypes, the blockers in Fig. 1 were applied successively in the order shown, with nifedipine present in all solutions after its initial application. All results are reported as mean ± SEM.

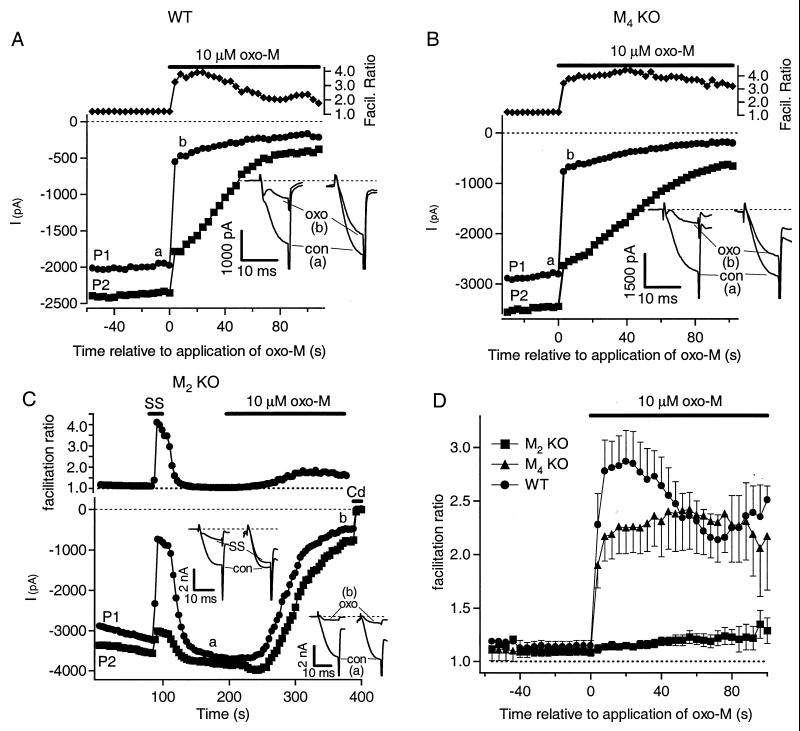

Figure 1.

Subtypes of Ca2+ channels in mouse SCG neurons from wild-type and M1 KO mice. Bars show the mean blockade of peak ICa by nifedipine (1 μM), ω-CTX GVIA (1 μM), and ω-CTX MVIIC (10 μM), applied successively in that order. Also shown is the residual current after application of all the blockers.

RESULTS

Contribution of N-, P/Q-, and L-type Channels to Total ICa in Mouse SCG Cells. In a series of studies, this lab and others have characterized modulation of Ca2+ channels of neurons acutely isolated from rat SCG. Because the experiments described here necessarily involved mouse cells, we determined whether mouse and rat neurons have the same properties. We first compared the relative contribution of various Ca2+ channel types to the total ICa.

We find that the mix of Ca2+ channels is similar, but not identical. Rat SCG neurons display large ω-CTX GVIA-sensitive N-type and small dihydropyridine (DHP)-sensitive L-type Ca2+ currents (ICa) that reach a maximum near 0 mV with 5 mM Ca2+ in the bath (12, 21, 22). To determine relative channel contributions in our mice, we applied blockers specific for particular Ca2+ channel types. Fig. 1 summarizes the progressive blockade of ICa by nifedipine (L-type), ω-CTX GVIA (N-type), and ω-CTX MVIIC (N- and P/Q-type). We studied cells from wild-type mice and from mice lacking M1 receptors (M1 KO mice) and found only small differences in blocker sensitivity between the two mouse strains. The results for wild-type and M1 KO cells, respectively, were 18 ± 2% (n = 12) and 19 ± 3% (n = 15) block with the DHP nifedipine (1 μM); 50 ± 2% (n = 13) and 38 ± 2% (n = 14) additional block with ω-CTX GVIA (1 μM); and 25 ± 2% (n = 6) and 22 ± 3% (n = 3) additional block with ω-CTX MVIIC (10 μM). For wild-type and M1 KO mice, 10 ± 2% (n = 6) and 13 ± 2% (n = 3) of the initial current remained in the presence of all three blockers. The principal differences in the Ca2+ currents of rat and mouse SCG seen here and in an earlier analysis (31) is in the fraction of current blocked by the two conotoxins. The fraction of channels blocked by ω-CTX GVIA is less in mouse than in rat, and the fraction of channels subsequently blocked by ω-CTX MVIIC is more, suggesting that in mouse there is not only a large N-type Ca2+ channel population but also a significant population of P/Q-type channels that is not seen in rat. As judged from our nifedipine results, the contribution of L-type Ca2+ channels (18%) may be a little greater in mouse than in rat neurons [often <10%, (21, 32)].

Slow, NEM-Insensitive Inhibition of N- and P/Q-Type Ca2+ Channels Is Mediated by M1 Receptors. Muscarinic modulation of Ca2+ currents was qualitatively similar in rat and mouse neurons. In rat SCG neurons, fast, voltage-dependent muscarinic inhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels can be selectively prevented by prior treatments with PTX or NEM. At low concentrations, NEM acts much like PTX in blocking the actions of Gi/Go class G proteins (33), and it does not block the slow muscarinic pathway, which uses different G proteins (34). Fig. 2A illustrates muscarinic modulation of M current and the action of NEM in a neuron from a wild-type mouse. The first application of oxo-M (before NEM) produced a large inhibition of ICa that resembles the biphasic fast and slow action in rat, reflecting the concurrent modulation of channels via two G-protein pathways. After washout of oxo-M and recovery of ICa, brief treatment with NEM (2 min, 50 μM) selectively abolished the fast muscarinic action, as seen by the second application of oxo-M, which then produced a smaller, and uniformly slower, inhibition of the current. Thus, NEM treatment isolates a slow muscarinic modulation in mouse, as in rat.

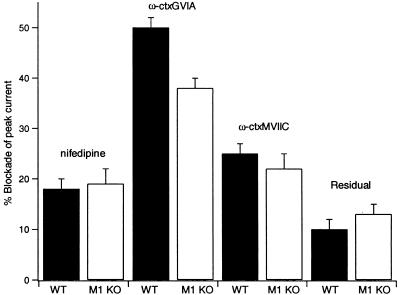

Figure 2.

The slow muscarinic pathway is mediated by M1 receptors. Amplitudes of peak ICa from depolarizations to 0 mV for a cell from a wild-type mouse (A) or an M1 KO mouse (B) are plotted at 2-s intervals. oxo-M (10 μM), NEM (50 μM), and Cd2+ (100 μM) were bath-applied during the times indicated by the bars. Current traces at the indicated times are shown in the Insets. (C) Bars show the mean inhibition by oxo-M before and after NEM treatment in wild-type and M1 KO mice.

To ask which mAChR mediates this slow action we performed the same experiment in cells from M1 KO mice. In the absence of M1 receptors, the first application of oxo-M produced a robust inhibition of ICa that appears entirely fast (Fig. 2B). NEM treatment nearly abolished the inhibition, as seen by the very weak response to the second oxo-M application. No evidence of slow muscarinic inhibition was seen either before or after NEM treatment. Such data are summarized in Fig. 2C. In cells from wild-type mice, oxo-M inhibited ICa by 63 ± 5% (n = 9) before NEM treatment, and by 35 ± 4% (n = 9) afterward, similar to results in the rat (34). In cells from M1 KO mice, the inhibition by oxo-M was 37 ± 4% (n = 12) before NEM treatment and only 10 ± 1% (n = 12) afterward. Thus, cells from wild-type mice show fast and slow actions on Ca2+ channels, and NEM occludes the fast action, leaving a robust slow inhibition by oxo-M, all as described in the rat. However, in the cells from M1 KO mice, muscarinic inhibition was uniformly fast, and largely sensitive to NEM, with little evidence of the slow muscarinic pathway. These observations show that M1 receptors are necessary for the slow inhibitory pathway in mouse SCG neurons.

Muscarinic Inhibition of L-type Ca2+ Channels Is Also Mediated by M1 Receptors.

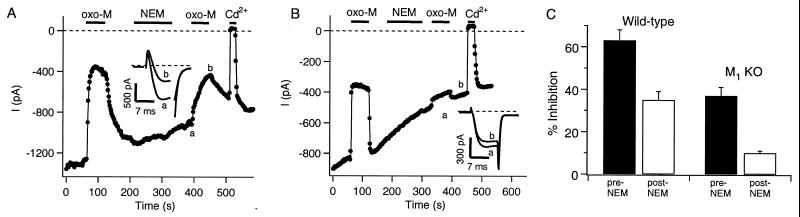

In rat SCG cells, small DHP-sensitive L-type Ca2+ currents are inhibited by muscarinic agonists via a pathway similar to that mediating the slow inhibition of N-type channels (26). We isolated L-type current in mouse neurons by prolonging its time course as a slow tail current following partial repolarization. We used the DHP agonist Bay K 8644 or the non-DHP agonist FPL 64176 (35, 36), which greatly slow deactivation of L-type, but not N- or P/Q-type channels. Test depolarizations were given to 0 mV, and muscarinic inhibition of L-type currents was quantified by measuring current 18–20 ms after stepping to the tail potential of −30 mV. Fig. 3A shows an experiment with a wild-type mouse neuron. Before application of FPL 64176, there is no slow tail current (Inset; the small outward current is probably due to some other conductance), but after the application an inward tail current develops. Subsequent application of oxo-M slowly suppressed this L-type current. In a neuron from an M1 KO mouse (Fig. 3B), FPL 64176 also produced a slow inward tail current, but oxo-M did not suppress the induced current at all. Such data are summarized in Fig. 3C. In the wild-type cells, inhibition of the FPL 64176-induced slow tail current by oxo-M was 53 ± 5% (n = 9), but in the M1 KO cells, the inhibition was only 8 ± 3% (n = 8). Thus, we conclude that, like slow muscarinic inhibition of N-type channels, the inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels requires M1 receptors. Our previous work with these M1 KO mice showed that the inhibition of M-current K+ channels also requires M1 receptors (28).

Figure 3.

Muscarinic inhibition of L-type channels is mediated by M1 receptors. Plotted are amplitudes of tail currents measured 18–20 ms after stepping to a potential of −30 mV in a cell from a wild-type mouse (A) or an M1 KO mouse (B). Depolarizations to 0 mV were applied every 4 s to elicit ICa, and FPL 64176 (1 μM), oxo-M (10 μM), and Cd2+ (100 μM) were bath-applied during the times indicated by the bars. Tail current traces at the indicated times are shown in the Insets. (C) Bars show the mean inhibition of the slow tail current by oxo-M in wild-type and M1 KO mice.

Fast, Voltage-Dependent Inhibition of N- and P/Q-Type Ca2+ Channels Is Mediated by M2 Receptors. We next determined which subtype of mAChR mediates fast, voltage-dependent inhibition of Ca2+ channels. To assay the voltage dependence of inhibition we used a double-pulse protocol (37). Two test pulses were given in succession, with a brief, strong depolarizing prepulse preceding the second test pulse. This prepulse promotes transient relief from voltage-dependent inhibition by driving G-protein βγ subunits off the inhibited channel (5, 38). The resulting facilitation of current is a characteristic signature: if the inhibition is voltage dependent, the current in the second pulse is inhibited less than the current in the first pulse (37). In rat SCG cells, we had been able to study the fast pathway in isolation by depressing the slow pathway selectively with 20 mM BAPTA in the pipette (internal) solution (12). However, we found this treatment relatively ineffectual in the mouse, since even with this pipette solution, the strong depolarizing prepulse did not decrease the inhibition by oxo-M anywhere near as much as expected for a pure voltage-dependent response. For example, in wild-type mouse cells dialyzed with 20 mM BAPTA, the inhibition was 74 ± 4% in the first test pulse and 64 ± 6% (n = 10) in the second. We therefore exploited the >10-fold difference in speed of action between the two pathways (15) by focusing on the inhibition of ICa soon after addition of oxo-M. A brisker cell perfusion was used that changed the extracellular solution within several seconds, and all solutions contained 2 μM nifedipine to block L-type current. These experiments used the standard pipette solution with 0.1 mM BAPTA. As an additional attempt to reduce the contribution of the slow pathway, most of these cells were exposed for 1–5 hr to 2 μM m1 toxin from the mamba snake (39). This toxin is a poorly reversible antagonist of M1 receptors in rat and hamster, and it seemed to partially block the slow pathway in some of the cells.

Fig. 4A shows an experiment with a cell from a wild-type mouse in which the double-pulse protocol is applied every 4 s. Amplitudes of ICa elicited by each pulse are plotted together with the “facilitation ratio,” calculated as the amplitude in the second pulse divided by that in the first pulse. When oxo-M is first applied, there is an abrupt inhibition of the current in the first pulse (by about 60%) and a much smaller inhibition of the current in the second pulse. This fast muscarinic action produces an immediate rise in the facilitation ratio, reflecting voltage-dependent inhibition. In the continued presence of oxo-M, there develops a second, slower, inhibition of the current that is not voltage-dependent. The currents in the first and second pulses are inhibited equally by this slow component (by about 60%), but the inhibition is much more obvious in the second pulse because the current there is always larger. Although the cell in this experiment had been preincubated in the m1 mamba toxin, the slow pathway seems unimpaired.

To determine which mAChR mediates the fast action, we repeated such experiments on cells from M4 and M2 KO mice. In a cell from an M4 KO mouse (Fig. 4B), the results were indistinguishable from the experiment in Fig. 4A: a strong, biphasic inhibition of ICa, with obvious fast voltage-dependent and slow voltage-independent components. The picture was quite different, however, in a cell from an M2 KO mouse (Fig. 4C). The experiment started with a control application of somatostatin, whose action should be unaffected by the presence or absence of mAChRs. In rat, somatostatin inhibits N-type Ca2+ channels solely through the fast, voltage-dependent pathway (40, 41). Similarly, in the mouse, we found that application of somatostatin (250 nM) produced a rapid, voltage-dependent inhibition. This response confirms that the fast pathway is present in the cell under study. Nevertheless, subsequent application of oxo-M to this M2 KO cell failed to produce the fast, voltage-dependent inhibition seen in Fig. 4 A and B. Inhibition with oxo-M was uniformly slow and voltage-independent. In cells from M2 KO mice, inhibition by somatostatin was accompanied by a rapid spike in the facilitation ratio to a value near 4, but inhibition by oxo-M was accompanied only by a late, gentle rise in the calculated facilitation ratio as ICa fell to very low values. The late rise may be an artifact of taking the ratio of small numbers, or perhaps there is an increase in free G-protein βγ-subunits liberated from continued activation of Gq/11 that contributes a small voltage-dependent inhibition.

Fig. 4D summarizes the facilitation ratios for all cells from these three groups of mice. Upon addition of oxo-M to cells from wild-type and M4 KO mice, there is a rapid increase in the facilitation ratio, reflecting action of the fast, voltage-dependent pathway. This increase in the facilitation ratio is almost completely absent in cells from M2 KO mice. Thus, we conclude that the fast voltage-dependent muscarinic signaling pathway that inhibits mouse N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels is mediated only by M2 receptors. Evidently, in the mouse, M4 receptors do not make a significant contribution.

DISCUSSION

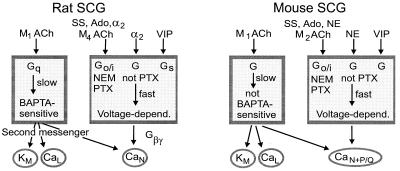

Fig. 5 summarizes the conclusions of our studies and several others as a comparison of several signaling pathways in mouse and rat SCG neurons. Both neurons express N- and L-type Ca2+ channels and M-type K+ channels. Additionally, in agreement with Namkung et al. (31), we find in mice a significant population of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels that is not present in rat. There are two principal signaling pathways in mouse, as in rat. As has been deduced from pharmacological experiments with antagonists in rats (25, 27), a slow pathway triggered by M1 mAChRs modulates all high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels and depresses M-current (28) in mouse. The G protein involved in this pathway is not sensitive to NEM and seems likely to be of the Gq/11 class also. Unlike in rat, this pathway apparently remains functional in mouse SCG neurons dialyzed with 20 mM BAPTA. In addition, mouse and rat have a fast muscarinic pathway that produces voltage-dependent inhibition of N-type channels. Similar fast modulation can also be activated by somatostatin, 2-chloroadenosine, norepinephrine, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) in both species (31). In mouse, the muscarinic action is NEM sensitive, the somatostatin and adenosine actions are fully PTX sensitive, and the norepinephrine action is partially PTX sensitive. A significant difference between rat and mouse is that the fast muscarinic pathway uses M2 receptors in the mouse, whereas, by criteria of himbacine, pirenzepine, and tripitramine sensitivity, it has a pharmacological profile most consistent with M4 receptors in the rat (25, 27). Another difference between rat and mouse lies in the expressed Ca2+ channel subtypes. Our conotoxin experiments and those of the Tsien laboratory (31) suggest that mouse cells express a significant P/Q-type Ca2+ channel population, whereas rat SCG neurons do not (42). A potential alternative interpretation is that mouse cells express alternatively spliced forms of N-type Ca2+ channels (43, 44) that are resistant to block by ω-CTX GVIA.

Figure 5.

Comparison of modulatory pathways in rat and mouse SCG neurons. Above are the names of receptors or agonists. Known characteristic features of the two major pathways are in boxes. Channel targets are below. Abbreviations: M ACh, mAChRs; SS, somatostatin; Ado, adenosine; α2, α2-adrenergic receptors; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide; NE, norepinephrine; Gβγ, G-protein βγ subunits. Data for rat are mostly from the review of ref. 6, and data for mouse are from this study and refs. 28 and 31, and B. P. Bean, personal communication.

The results on the slow pathway were mostly expected. The M1 mAChR mediates a slow signal that depresses M-current and several types of high-voltage-activated Ca2+ currents in rat and mouse. These results mean that mouse cells, mouse M1 receptors, and mouse M-channels and Ca2+ channels can be used in future experiments aimed at uncovering the unknown diffusible messenger that is generated by means of M1 receptors to modulate the M- and Ca2+ channels. The lack of sensitivity to internal 20 mM BAPTA in mouse reinforces our earlier conclusion that the unknown messenger of the slow muscarinic pathway is not the free calcium ion (12, 45, 46).

On the other hand, the results on the fast pathway were surprising. This pathway has the pharmacological properties of M4 receptors in rat (25), yet mice totally lacking M4 receptors had no detectable deficit in the fast modulation of Ca2+ channels. Instead, knockout of M2 receptors was required to eliminate the fast pathway. We undertook these experiments with KO mice because of reports of M2 receptors in sympathetic neurons. Rabbit sympathetic neurons showed large numbers of immunoreactive M1 and M2 receptors and only a small population of M4 receptors (47), and rat SCG neurons contained mRNA for M1, M2, and M4 receptors (48). Very recent observations have clarified the picture. First, the assignment of M4 receptors to the fast pathway of rat SCG has been reinforced by further pharmacological experiments (27). Second, a distinct function for pharmacologically defined M2 receptors has been found in the same cells. When G-protein-regulated inward rectifiers (GIRK channels) are expressed exogenously in rat SCG cells, their muscarinic activation uses pharmacologically defined M2 receptors but not the M4 receptors that are also present (27). Thus M2 and M4 receptors coexist in rat SCG neurons but are coupled to different effectors. We conclude that rats and mice differ in which even-numbered muscarinic receptors couple to G proteins to modulate Ca2+ channels. Analogous results have been reported when different criteria were used. Muscarinic antinociception is clearly mediated via M2 receptors in mouse (29) but is said to have a pharmacology more consistent with other receptor subtypes in rat (49).

Genetic ablation of a signaling protein may induce compensatory responses, wherein other proteins take over the roles normally mediated by the targeted protein. Thus, mice lacking Go-class G proteins still exhibit PTX-sensitive voltage-dependent inhibition of Ca2+ channels, even for receptors that normally act via Go (ref. 50; B. P. Bean, personal communication). These Go KO mice may compensate for the lack of Go proteins by using Gi class G proteins instead, producing a somewhat altered, but still functional, PTX-sensitive signal. In other studies, loss of a specific gene led to nearly complete ablation of function. Thus, deletion of a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel yields mice that cannot smell—their olfactory neurons show no response to odorants (51). Similarly, disruption of the gene for the voltage-gated K+ channel Kv1.1 causes a central nervous system hyperexcitability reminiscent of epilepsy, presumably because no other K+ channel can compensate for the absence of Kv1.1 (52). Likewise, in our experiments the mAChR KO mice seem to lose specific modulatory signaling to ion channels without compensation by other muscarinic subtypes. Because sympathetic neurons modulate their ion channels through a wide spectrum of G-protein-coupled receptors, it may be that the loss of signaling from one mAChR does not have severe enough consequences to induce compensatory responses. Other work involving different effectors with mAChR subtype KO mice reached a similar conclusion (28, 29). Our experiments reemphasize the segregation of signaling from each of the mAChR subtypes.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Miller and D. Stienmier for technical help, and Ken Mackie for suggestions on the manuscript and for financial support. Our work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS08174 (to B.H.), NS26920 (to N.M.N.), and DA11322 (to Ken Mackie).

ABBREVIATIONS

- BAPTA

1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- DHP

dihydropyridine

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide, oxo-M, oxotremorine methiodide

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- SCG

superior cervical ganglion

- ω-CTX

ω-conotoxin

- mAChR

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor

- KO

knockout

References

- 1.Felder C C. FASEB J. 1995;9:619–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirning L D, Fox A P, McCleskey E W, Olivera B M, Thayer S A, Miller R J, Tsien R W. Science. 1988;239:57–61. doi: 10.1126/science.2447647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koh D S, Hille B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1506–1511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipscombe D, Kongsamut S, Tsien R W. Nature (London) 1989;340:639–642. doi: 10.1038/340639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bean B P. Nature (London) 1989;340:153–156. doi: 10.1038/340153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hille B. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolphin A C. J Physiol (London) 1998;506:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.003bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herlitze S, Garcia D E, Mackie K, Hille B, Scheuer T, Catterall W A. Nature (London) 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda S R. Nature (London) 1996;380:255–258. doi: 10.1038/380255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haley J E, Abogadie F C, Delmas P, Dayrell M, Vallis Y, Milligan G, Caulfield M P, Brown D A, Buckley N J. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4521–4531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delmas P, Brown D A, Dayrell M, Abogadie F C, Caulfield M P, Buckley N J. J Physiol (London) 1998;506:319–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.319bw.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beech D J, Bernheim L, Mathie A, Hille B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:652–656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beech D J, Bernheim L, Hille B. Neuron. 1992;8:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90111-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernheim L, Beech D J, Hille B. Neuron. 1991;6:859–867. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90226-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J, Shapiro M S, Hille B. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2040–2048. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams P R, Brown D A, Constanti A. J Physiol (London) 1982;332:223–262. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown D A, Adams P R. Nature (London) 1980;283:673–676. doi: 10.1038/283673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caulfield M P, Jones S, Vallis Y, Buckley N J, Kim G D, Milligan G, Brown D A. J Physiol (London) 1994;477:415–422. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro M S, Wollmuth L P, Hille B. Neuron. 1994;12:1319–1329. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown D A, Abogadie F C, Allen T G, Buckley N J, Caulfield M P, Delmas P, Haley J E, Lamas J A, Selyanko A A. Life Sci. 1997;60:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plummer M R, Logothetis D E, Hess P. Neuron. 1989;2:1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regan L J, Sah D W, Bean B P. Neuron. 1991;6:269–280. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen C, Schofield G G. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1440–1450. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wanke E, Ferroni A, Malgaroli A, Ambrosini A, Pozzan T, Meldolesi J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4313–4317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernheim L, Mathie A, Hille B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9544–9548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathie A, Bernheim L, Hille B. Neuron. 1992;8:907–914. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90205-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez-Fernandez J M, Wanaverbecq N, Halley P, Caulfield M P, Brown D A. J Physiol (London) 1999;515:631–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.631ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton S E, Loose M D, Qi M, Levey A I, Hille B, McKnight G S, Idzerda R L, Nathanson N M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13311–13316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomeza J, Shannon H, Kostenis E, Felder C, Zhang L, Brodkin J, Grinberg A, Sheng H, Wess J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1692–1697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomeza, J., Zhang, L., Shannon, H., Kostenis, E., Felder, C., Brodkin, J., Grinberg, A., Sheng, H. & Wess, J. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA96, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Namkung Y, Smith S M, Lee S B, Skrypnyk N V, Kim H L, Chin H, Scheller R H, Tsien R W, Shin H S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12010–12015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutton K G, Siok C, Stea A, Zamponi G W, Heck S D, Volkmann R A, Ahlijanian M K, Snutch T P. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:407–418. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakajima T, Kaibara M, Irisawa H, Giles W. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1991;343:14–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00180671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shapiro M S, Wollmuth L P, Hille B. J Neurosci. 1994;14:7109–7116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-07109.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rampe D, Lacerda A E. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259:982–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng W, Rampe D, Triggle D J. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40:734–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeda S R. J Physiol (London) 1991;439:181–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elmslie K S, Zhou W, Jones S W. Neuron. 1990;5:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90035-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Max S I, Liang J S, Potter L T. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4293–4300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04293.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeda S R, Schofield G G. J Physiol (London) 1989;409:221–240. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapiro M S, Hille B. Neuron. 1993;10:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90237-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mintz I M, Adams M E, Bean B P. Neuron. 1992;9:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rittenhouse A R, Hess P. J Physiol (London) 1994;474:87–99. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin Z, Haus S, Edgerton J, Lipscombe D. Neuron. 1997;18:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfaffinger P J, Leibowitz M D, Subers E M, Nathanson N M, Almers W, Hille B. Neuron. 1988;1:477–484. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cruzblanca H, Koh D S, Hille B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7151–7156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorje F, Levey A I, Brann M R. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40:459–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown D A, Buckley N J, Caulfield M P, Duffy S M, Jones S, Lamas J A, Marsh S J, Robbins J, Selyanko A A. In: Molecular Mechanisms of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Function. Wess J, editor. Austin, TX: Lanes; 1995. pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naguib M, Yaksh T L. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:847–853. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang M, Gold M S, Boulay G, Spicher K, Peyton M, Brabet P, Srinivasan Y, Rudolph U, Ellison G, Birnbaumer L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3269–3274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brunet L J, Gold G H, Ngai J. Neuron. 1996;17:681–693. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smart S L, Lopantsev V, Zhang C L, Robbins C A, Wang H, Chiu S Y, Schwartzkroin P A, Messing A, Tempel B L. Neuron. 1998;20:809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]