Abstract

Forty-one methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) hospital isolates that clearly differed from the six major pandemic clones of MRSA in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis type, mecA and Tn554 polymorphism, and epidemic behavior were selected from an international strain collection for more detailed characterization. SpaA typing, multilocus sequence typing, and SCCmec (staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec) typing demonstrated extensive diversity among these sporadic isolates both in genetic background and also in the structure of the associated SCCmec elements. Nevertheless, the isolates could be grouped into restricted clonal complexes by using the BURST (i.e., based upon related sequence types) program algorithm, which predicted that most sporadic MRSA isolates evolved from pandemic MRSA clones. Several of the sporadic MRSA resembled community-acquired MRSA isolates in properties that included a relatively limited multiresistance pattern, faster growth rates, diversity of genetic backgrounds, and a frequent association with SCCmec type IV.

In our previous studies we characterized over 3,000 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates collected in surveillance studies and outbreak investigations in hospitals located in southern and eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia between 1992 and 2001 through the CEM/NET (11, 33) and the RESIST (31) international initiatives. The combination of molecular typing techniques, specifically pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), ClaI-mecA polymorphisms, and Tn554 insertion patterns allowed us to identify six epidemic MRSA clones that were widely disseminated in these geographic areas. A common feature of these epidemic clones was their dominance: we noted frequent recovery from patients both within a single hospital and also in hospitals located over vast geographic distances. These six expansively spread clones accounted for a large proportion (nearly 70%) of the over 3,000 MRSA isolates previously characterized by our group, indicating that they represented successful lineages in terms of ability to cause infection, to persist, and to spread even across continents (30).

The same molecular typing techniques also identified MRSA lineages that, in contrast to these epidemic clones, were clearly dominant only in single hospitals but were not seen in others (referred to here as “minor” clones). A third type of epidemic behavior was that of MRSA isolates with diverse molecular types that were recovered only from a few patients even in single hospitals (referred to here as “sporadic” MRSA isolates).

Application of spaA typing, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and SCCmec (for staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec) typing confirmed the existence of and helped to better define the nature and evolutionary relationships among the six epidemic clones (14, 30). However, the evolutionary origins of minor MRSA clones and sporadic isolates are not well understood; the reason why they seem unable to spread also remains unknown. The study described here addresses some of these issues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 41 hospital-acquired MRSA isolates were selected for the present study from strain collections performed in 12 countries between 1992 and 2001 (1-5, 7, 18, 20, 23) (Table 1). All 41 isolates have already been characterized in previous studies by antibiogram and by three molecular typing techniques: hybridization of ClaI restriction digests with the mecA- and Tn554-specific DNA probes combined with PFGE of chromosomal SmaI digests, generating corresponding “clonal types” (ClaI-mecA::ClaI-Tn554::PFGE) (10). Each of the 41 MRSA isolates had a unique clonal type as determined from these criteria, and none of the 41 clonal types resembled the clonal types characteristic of the six major pandemic MRSA designated the Iberian, Brazilian, Hungarian, New York/Japan, Pediatric, or EMRSA-16 clones. A common feature of these 41 strains was their epidemic behavior: they represented either minor clones (i.e., they were frequently recovered from patients but only in one hospital) or they were sporadic isolates (i.e., they were recovered only from one or a few patients in a single hospital). For the sake of simplicity we are going to refer to both of these MRSA types as sporadic isolates throughout the rest of the present study.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of the minor clones and sporadic isolates included in this study relative to other clones found in previous studiesa

| Country and strain | Clonal type | Prevalence (%) | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | |||

| HSA10 | III::α::A | 2 | 5 |

| HSA49 | V::NH::B | 1 | 5 |

| HGSA9 | XI::B::g | 3 | 5 |

| HGSA128 | XI::NH::D1 | 1 | 5 |

| NA | Iberian | 29 | 5 |

| NA | Brazilian | 56 | 5 |

| NA | Other | 8 | 5 |

| IPOP2 | II::NA::D2 | 23 | L |

| NA | Brazilian | 60 | L |

| NA | Other | 17 | L |

| Italy | |||

| ITL262 | II::NH::E | 12 | M |

| ITL592 | II::E::F | 38 | M |

| ITL113 | II::E::G | 3 | M |

| NA | Iberian | 29 | M |

| NA | Brazilian | 13 | M |

| NA | Other | 5 | M |

| Turkey | |||

| TUR4 | II::ηη::H | 39 | L |

| TUR9 | III::A::I | 15 | L |

| TUR1 | III::A::J | 3 | L |

| TUR27 | II::D::I | 3 | L |

| NA | Other | 40 | L |

| Greece | |||

| GRE14 | II::NH::K | 9 | 1 |

| GRE120 | II::E::L | 1 | 1 |

| GRE108 | III::B::M | 1 | 1 |

| NA | Brazilian | 60 | 1 |

| NA | EMRSA-16 | 29 | 1 |

| Czech Republic | |||

| CR1 | II::NH::P | 2 | 23 |

| CR43 | I::NH::O | 2 | 23 |

| NA | Iberian | 12 | 23 |

| NA | Brazilian | 80 | 23 |

| NA | Other | 4 | 23 |

| Poland | |||

| PLN49 | II::NH::N | 3 | 20 |

| NA | Polish | 75 | 20 |

| NA | Other | 22 | 20 |

| Chile | |||

| CHL5 | II::E′::Q | 43 | 4 |

| CHL63 | II::E′::Q | 43 | |

| NA | Brazilian | 57 | 4 |

| Colombia | |||

| COBIII | II::NH::R | 1 | 18 |

| NA | Pediatric | 99 | 18 |

| Argentina | |||

| ARG33 | II::E::S | 6 | 4, 7 |

| ARG127 | II::NH::T | <1 | 4, 7 |

| ARG229 | I::NH::U | <1 | 4, 7 |

| ARG199 | I::NH::V | <1 | 4, 7 |

| ARG64 | II::EE::X | <1 | 4, 7 |

| ARG105 | II::E::W | 1 | 4, 7 |

| AGT42 | IX::OO::Y | 1 | 4, 7 |

| AGT30 | XI::E::W | 1 | 4, 7 |

| AGT55 | IX::E::a | 1 | 4, 7 |

| NA | Brazilian | 70 | 4, 7 |

| NA | Pediatric | 11 | 4, 7 |

| NA | Other | 5 | 4, 7 |

| Brazil | |||

| BZ40 | I::E::C | 1 | 4 |

| BZ48 | III:B::E | 1 | 4 |

| BZ14 | II::E::F | 1 | 4 |

| NA | Brazilian | 97 | 4 |

| Japan | |||

| JP84 | I::J::b | 1 | 3 |

| JP82 | I′::NH::c | 1 | 3 |

| JP87 | I::A::d | 1 | 3 |

| JP26 | I::A::e | 1 | 3 |

| JP238 | I::A::f | 1 | 3 |

| NA | NY/Japan | 92 | 3 |

| NA | Other | 3 | 3 |

| Taiwan | |||

| TAW97 | XI::B::C | 3 | 2 |

| TAW214 | II::NH::h | 1.5 | 2 |

| TAW166 | II::ZZ::i | 1.5 | 2 |

| NA | Hungarian | 94 | 2 |

NA, not available (that is, clonal types not included in this study).

L, H. de Lencastre et al., unpublished data; M, R. Mato et al., unpublished data.

Susceptibility tests.

Confirmatory susceptibility tests were performed for some isolates in the present study by the standard disk diffusion method or by the agar dilution method according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines (24, 25) against penicillin, oxacillin, erythromycin, gentamicin, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, rifampin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and vancomycin (all from Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England).

Doubling time.

Growth in tryptic soy broth was measured at 660 nm by using a Spectronic 21 (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, N.Y.). The doubling time during the exponential growth phase was determined at an optical density of ca. 0.02 to 1.0 as previously described (17). Strains N315 and MW2 were used as controls.

Detection of PVL genes.

Sequences specific for Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) genes (lukS-PV-lukF-PV) were detected by PCR as described elsewhere (21).

SCCmec type assignment.

The SCCmec types were determined by a multiplex PCR strategy (28). For all isolates classified as SCCmec type IV and whenever at least one of the structural features shown to be typical of a particular SCCmec type was not identified by this methodology, we used the PCR amplification of the ccr (for cassette chromosome recombinase) gene and the mec gene complex (26).

spaA typing.

Molecular typing based on the sequence of the polymorphic region of the protein A (spaA typing) was performed as described previously (32). The primers used were as follows: spaAF1, 5′-GAC GAT CCT TCG GTG AGC-3′, nucleotides 1096 to 1113; and spaAR1, 5′-CAG CAG TAG TGC CGT TTG C-3′, nucleotides 1534 to 1516 (accession no. J01786) (27).

MLST.

MLST was performed according to a previously described procedure (13), with the exception of primer arcCF2 (5′-CCT TTA TTT GAT TCA CCA GCG-3′) (8). Sequences of both strands were determined by using an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer by using the BigDye fluorescent terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) at the DNA sequencing facilities at the Instituto Gulbenkian da Ciência, Oeiras, Portugal, or by using ABI Prism 3700 genetic analyzers at The Rockefeller University, New York, N.Y., and Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea. The allelic profiles of all strains, defined by the alleles at the seven MLST loci in the order arcC-aroE-glpF-gmk-pta-tpi-yqiL, were compared by using the program BURST (based upon related sequence types [STs]).

BURST analysis.

BURST is a clustering algorithm, developed by Feil et al. (15), used to group isolates that have similar STs into a clonal complex (CC) and to anticipate the evolutionary origin of the isolates in each cluster from a putative ancestral allelic profile. Every genotype included in a CC shares at least five loci and an ancestral genotype is the allelic profile that has the highest number of single-locus variants (SLVs). Single genotypes that do not correspond to any CC are identified as singletons. Further details are available elsewhere (http://www.mlst.net/BURST/burst.htm).

RESULTS

Variation in the SCCmec types associated with sporadic MRSA isolates and identification of new structural variants of SCCmec.

Using the recently developed multiplex PCR strategy (28), we identified SCCmec type I in 11 strains, SCCmec type II in 3 strains, SCCmec type III in 10 strains, and SCCmec type IV in 13 strains. Four isolates harbored two novel SCCmec structural types, which we designated new1 and new2. SCCmec types I, II, III, and IV were associated with 6, 2, 2, and 11 different STs, respectively (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic and genotypic properties of 41 MRSA isolates belonging to minor clones or sporadic isolates present in hospitals

| Country and strain | Yr of isolation | Antibiograma

|

Clonal type | spaA type | ST | MLST | CCb | SCCmec typec | ccr type | mec complex | luk-PVd | Doubling time (min)e | Source or reference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN | OXA | ERY | GEN | CLI | CHL | CIP | RIF | TET | SXT | VAN | |||||||||||||

| Portugal | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| HSA10 | 1992 | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S | S | III::α::A | WGKAOM | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | NT-III | 3 | A | − | 32.85 | 5 |

| HSA49 | 1993 | R | R | S | R | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | V::NH::B | TJMBMDMGMK | 5 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | IV | 2 | B | − | 25.96 | 5 |

| HGSA9 | 1997 | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | I | S | R | S | XI::B::g | Nontypeable | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | IIIA | − | 26.62 | 5 | ||

| HGSA128 | 2000 | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | XI::NH::D1 | TJJEJNI2MNI2MOMOKR | 79 | 7-6-1-33-8-8-6 | 22 | IV | 2 | B | − | 25.02 | 5 |

| IPOP2 | 2001 | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | II::NA::D2 | TJJEJNI2MN12MOMOKR | 22 | 7-6-1-5-8-8-6 | 22 | IV | 2 | B | − | 29.12 | This study |

| Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ITL262 | 1997 | R | R | S | R | S | S | R | R | R | S | S | II::NH::E | YHFGFMBQBLO | 247 | 3-3-1-12-4-4-16 | 8 | I | − | 26.97 | -f | ||

| ITL592 | 1998 | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | S | S | II::E::F | TIMBMDMBMDMGMK | 228 | 1-4-1-4-12-24-29 | 5 | I | − | 34.66 | - | ||

| ITL113 | 1997 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | II::E::G | TIMBMBMDMGMK | 228 | 1-4-1-4-12-24-29 | 5 | I | − | 30.94 | - | ||

| Turkey | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| TUR4 | 1996 | R | R | I | R | S | S | R | R | R | S | S | II::ηη::H | WGKAQQ | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | III | − | 29.62 | This study | ||

| TUR9 | 1995 | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | S | S | III::A::I2 | WGKAQQ | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | III | − | 31.65 | This study | ||

| TUR1 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | S | S | III::A::J | WGKAQQ | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | III | − | 27.84 | This study | ||

| TUR27 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R | R | S | S | II::D::II | WGKAQQ | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | III | − | 30.01 | This study | ||

| Greece | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| GRE14 | 1998 | R | R | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | II::NH::K | UJGBBPB | 80 | 1-3-1-14-11-51-10 | S | IV | 2 | B | + | 26.56 | 1 |

| GRE120 | 1993 | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | R | R | S | II::E::L | YGFMBQBLPO | 8 | 3-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | IV | 2 | B | − | 30.27 | 1 |

| GRE108 | 1998 | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R | R | S | III::B::M | XKAOMMQ | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | III | − | 32.24 | 1 | ||

| Czech Republic | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| CR1 | 1996 | R | R | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | II::NH::N | YGFMBQBLO | 8 | 3-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | IV | 2 | B | − | 25.67 | 23 |

| CR43 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | S | S | I::NH::O | YHGFMBQBLO | 8 | 3-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | IV | 2 | B | − | 33.81 | 23 |

| Poland (PLN49) | 1997 | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | II::NH::P | XKAKBEMBKB | 45 | 10-14-8-6-10-3-2 | 45 | IV | 2 | B | − | 27.18 | 20 |

| Chile | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| CHL5 | 1997 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | S | II::E′::Q2 | TMK | 83 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-1 | 5 | I | − | 33.32 | 4 | ||

| CHL63 | 1997 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | I | S | S | II::E::Q1 | TIMEMDMGMGMK | 5 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | I | − | 31.22 | 4 | ||

| Colombia (COB111) | 1998 | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | II::NH::R | JCMBPB | 84 | 1-26-28-32-18-33-27 | 91 | IV | 2 | B | − | 30.81 | 18 |

| Argentina | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ARG33 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | S | S | S | II::E::S | TIMBMDMGMK | 85 | 31-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | IIIA | − | 31.94 | 7 | ||

| ARG127 | 1995 | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | II::NH::T | WGKAKAOMQQ | 30 | 2-2-2-2-6-3-2 | 30 | IVA | 2 | B | − | 34.15 | 7 |

| ARG229 | 1995 | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | I::NH::U | TJMBMDMGMK | 100 | 1-65-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | IV-new1 | 2 | None | − | 30.67 | 7 |

| ARG199 | 1996 | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | I::NH::V | UJGFGMDMGGM | 86 | 2-4-1-8-4-4-3 | 8 | IVA-new1 | 2 | None | − | 28.18 | 7 |

| ARG64 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | R | S | II::EE::X | TIMBMDMGMK | 85 | 31-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | I | − | 35.91 | 7 | ||

| ARG105 | 1995 | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | I | R | S | S | II::E::WI | YHFGFMBQBLO | 247 | 3-3-1-12-4-4-16 | 8 | IV-new2 | None | None | − | 35.01 | 7 |

| AGT42 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | IX::OO::Y | TIMBMDMGMK | 5 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | I | − | 30.54 | 4 | ||

| AGT30 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | S | S | XI::E::W2 | YHFGFMBQBLO | 247 | 3-3-1-12-4-4-16 | 8 | IV-new2 | None | None | − | 30.54 | 4 |

| AGT55 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | IX::E::a | UMDJMGMK | 5 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | I | − | 28.18 | 4 | ||

| Brazil | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| BZ40 | 1996 | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | S | R | S | I::E::Z1 | TMK | 5 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | I | − | 29.62 | 4 | ||

| BZ48 | 1997 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | III::B::C1 | Nontypeable | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | IIIA | − | 34.31 | 4 | ||

| BZ14 | 1996 | R | R | I | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | S | II::E::Z1 | TMK | 5 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | I | − | 29.75 | 4 | ||

| Japan | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| JP84 | 1997 | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | I::J::b | YHHGFMBQQBLO | 8 | 3-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | I | − | 27.51 | 3 | ||

| JP82 | 1997 | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | I′::NH::c | EJCMBPB | 92 | 1-26-28-18-18-54-27 | 91 | IVA | 2 | B | − | 28.64 | 3 |

| JP87 | 1997 | R | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | I::A::d | EJCMBPB | 89 | 1-26-28-18-18-33-50 | 91 | II′ | 2 | A | − | 27.95 | 3 |

| JP26 | 1997 | R | R | R | S | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | I::A::e | TJMBMDMGMK | 5 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | II | − | 24.93 | 3 | ||

| JP238 | 1998 | R | R | R | R | S | S | I | S | S | S | S | I::A::f | TDMGMK | 5 | 1-4-1-4-12-1-10 | 5 | II′′ | 2 | A | − | 27.84 | 3 |

| Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| TAW97 | 1998 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | XI::B::C2 | WGKAOMQ | 239 | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | IIIA | − | 34.48 | 2 | ||

| TAW214 | 1998 | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | II::NH::h | ZDMDMOB | 59 | 19-23-15-2-19-20-15 | S | IV | 2 | B | − | 28.41 | 2 |

| TAW166 | 1998 | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | S | II::ZZ::j | Nontypeable | 81 | 3-32-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | NT-IV | 2 | B | − | 34.31 | 2 |

Antibiotic abbreviations: PEN, penicillin; OXA, oxacillin; ERY, erythromycin; GEN, gentamicin; CLI, clindamycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; RIF, rifampin; TET, tetracycline; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; VAN, vancomycin. A few isolates were tested for fusidic acid and teicoplanin resistance. R, resistant, S, susceptible; I, intermediate.

Based on BURST. S, singleton (not assigned to any clonal complex).

NT, isolate considered nontypeable by the multiplex strategy due to extra or missing amplification fragments relatively to the described patterns.

luk-PV genes encode PVL. +, presence of PVL determinant; −, absence of PVL determinant.

Doubling time during exponential growth phase.

-, R. Mato et al., unpublished data.

For four isolates (HSA10, JP87, JP238, and TAW166), the SCCmec type could not be directly inferred by the multiplex PCR strategy since the amplification patterns observed did not exactly correspond to the ones described by Oliveira et al. (28). For these four isolates, SCCmec types were determined by PCR typing the mec gene and the ccr gene complexes (26). Isolate HSA10 had ccr type 3 and mec complex type A and was therefore classified as SCCmec type III (19). However, by the multiplex PCR strategy it was determined that there was amplification of the locus corresponding to the dcs region that was not detectable in the SCCmec type III of previously characterized MRSA strains (19, 28, 29).

Isolates JP87 and JP238 had ccr type 2 and mec complex type A and were therefore classified as SCCmec type II (19). However, by the multiplex PCR strategy there was no amplification of the locus corresponding to the kdp operon (29) or the locus corresponding to the mecI gene, in spite of the fact that both of these genes were present in previously characterized SCCmec type II (19, 29). Isolate TAW166 had ccr type 2 and mec complex type B and was therefore classified as SCCmec type IV (22, 29). However, as determined by the multiplex PCR strategy there was amplification of a locus specific for SCCmec type III that is located in the region between Tn554 and the chromosomal right junction (orfX) (28). We concluded that these four isolates must be variants of the previously described SCCmec types II, III, and IV.

The 16 isolates that were identified as carrying SCCmec type IV or IVA on the basis of the multiplex strategy were also tested by PCR typing of the mec gene and ccr gene complexes. Four isolates were found to belong to new, hitherto-undescribed SCCmec types. Two of these—ARG199 and ARG229—had ccr type 2 but none of the mec gene complexes described so far. We coined a name for SCCmec type, new1, for these isolates. The two other isolates—ARG105 and AGT30—had both novel ccr types and novel mec gene complexes (19, 26), and we coined the SCCmec type designation new2 for these isolates. The new1 and new2 SCCmec types may represent unusually short sequences since they lacked all typical elements present in other cassette types.

Variation in spaA types of sporadic MRSA isolates.

Twenty-five distinct spaA types were found among the 41 MRSA isolates studied. Three isolates were nontypeable with the set of primers used. By analyzing the pattern of repeats, we could group spaA types that have similar repeat organizations into major spaA motifs. Of the 25 different spaA types, 8, 6, 5, and 2 were classified into the motifs DMGMK, KAOMQ, MBQBLO, and JCMBPB, respectively. Six spaA types did not fall into any of the four spaA motifs. The spaA types characteristic of the epidemic international clones included the motifs DMGMK (New York/Japan and Pediatric clones), KAOMQ (Brazilian, Hungarian, and EMRSA-16 clones), and MBQBLO (Iberian clone) (29).

Genetic diversity of sporadic MRSA.

MLST identified 19 STs among the 41 isolates (Table 2). Thirteen STs were each represented by a single MRSA isolate only. ST239 and ST5 were more frequent: they were identified in nine and eight isolates, respectively.

STs 5, 8, 85, and 247 included MRSA isolates that displayed different SCCmec types, whereas the nine MRSA isolates with ST239 all carried the uniform SCCmec type III. Three different SCCmec types were identified among ST5 isolates: ST5-I (five isolates), ST5-II (two isolates), and ST5-IV (one isolate). One MRSA isolate with ST8 was associated with SCCmec type I, and three isolates of ST8 were associated with SCCmec type IV. In the case of MRSA with ST247 one isolate was associated with SCCmec type I and two isolates were associated with SCCmec type new2. Each of the two ST85 isolates carried a different SCCmec type: SCCmec I and III.

Combining the ST and the SCCmec type, we identified 24 clonal types out of which clones ST239-III, ST5-I, and ST8-IV each were represented by three or more isolates. Of the 24 clonal types, four were identical to one of the six pandemic MRSA clones: ST239-III/IIIA (Brazilian/Hungarian clone) were represented by nine isolates, ST5-II (New York/Japan clone) were represented by two isolates, and ST247-I (Iberian clone) and ST5-IV (Pediatric clone) were represented by one isolate each (14, 29).

Evolutionary relationships among sporadic MRSA and pandemic clones of MRSA.

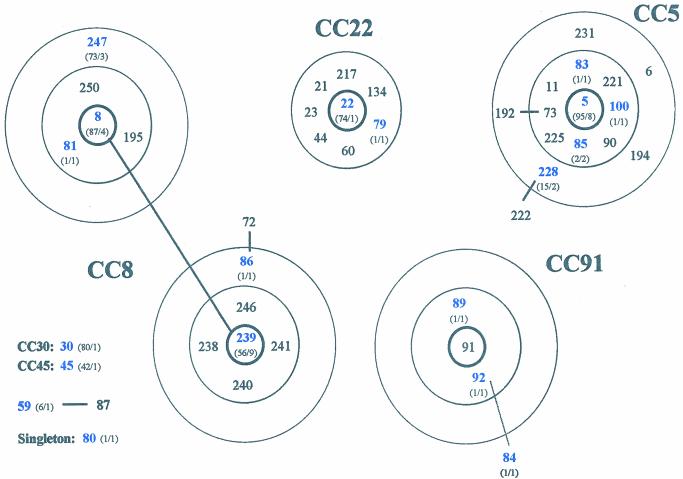

The algorithm BURST was used to identify groups of related genotypes, i.e., CCs, and to predict the ancestral genotype of each group and the most parsimonious patterns of descent from the corresponding ancestor. The BURST analyses distributed the sporadic MRSA isolates into several CCs. Five STs (ST8, ST86, ST239, ST247, and ST81), represented by 18 isolates, belonged to CC8. A second group of five STs (ST5, ST83, ST85, ST100, and ST228), represented by 14 isolates, belonged to CC5. Three STs (ST84, ST89, and ST92), represented by three isolates, belonged to CC91. Of additional CCs, CC22 had two isolates, and CC30 and CC45 each had one isolate. No ancestral genotype could be assigned to two isolates: one with ST59 and another with ST80. These STs were therefore considered singletons (Table 2). Although in our collection there was only a single ST30 and a single ST45 isolate, MRSA strains with these two clonal types are common in the United Kingdom and Germany: there are 80 ST30 strains and 42 ST45 strains deposited in the MLST database (www.mlst.net). Figure 1 shows the representation of the CCs identified by BURST in the present study that included at least two STs.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of CCs defined with the algorithm BURST. Each number represents an MLST-derived ST. The ST of the predicted ancestral genotype is placed in the central circle, SLVs are within the second circle, and DLVs within the outer dotted circle. One ST (ST59) for which an ancestral genotype cannot be inferred and one ST (ST80) that is not member of any CC (singletons) are also shown. CC30 and CC45 are not graphically represented since they are represented by unique STs in the present study. Blue numbers denote STs found in the present study; black numbers denote STs in the database associated with a particular CC. The numbers of isolates with a particular ST deposited in the database, followed by the numbers of isolates with that ST found in our study, e.g., “(73/3),” are given in parentheses.

Doubling time.

The doubling time during exponential growth was determined for the 41 isolates and varied between 24.93 and 35.91 min (Table 2). The mean doubling times ± the standard deviations for the 11 isolates of SCCmec type I, the 3 isolates of type II, the 10 isolates of type III, and the 13 isolates of type IV were 30.78 ± 3.81, 26.91 ± 1.98, 31.16 ± 4.54, and 29.22 ± 4.2 min, respectively. There was no clear difference between the growth rates of isolates harboring SCCmec type IV and isolates showing other SCCmec types. A Student t test was performed, revealing a P value of 0.194, which is clearly not significant. Strains MW2 and N315 used as controls showed growth rates of 28.67 and 33.32 min, respectively.

Detection of PVL genes.

PVL genes were detected in only 1 of the 41 MRSA isolates analyzed (Table 2). This isolate belonged to clone ST80-IV that we recently described (1).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to better understand the genetic backgrounds and evolutionary origin of MRSA isolates that we have been referring to as minor clones or sporadic MRSA isolates because of their epidemic behavior: they represented MRSA isolates with rare clonal types (PFGE patterns combined with mecA and Tn554 polymorphs) that were clearly different from the clonal types of the epidemic MRSA that were most frequently recovered from patients during the international surveillance studies conducted by our laboratory (1-5, 7, 18, 20, 23).

Clearly, there is a considerable degree of arbitrariness in this approach since MRSA clonal types classified as sporadic or minor in our particular surveillance studies may represent major clonal types in some other geographic area or at some other period of surveillance. Furthermore, although the typing method used for the identification of clonal types has high resolving power, it can also blur evolutionary relationships that may be clarified by applying MLST in combination with determination of the structure of SCCmec types carried by the bacteria. We used these DNA sequence-based methods to reexamine the nature of 41 sporadic MRSA isolates that did not belong to any of the six previously described pandemic MRSA clones as defined by ClaI-mecA::Tn554::PFGE types (29).

Based on MLST alone, 20 of the 41 MRSA isolates were determined to share the genotype of one or another of the six pandemic clones. However, based on MLST in combination with SCCmec typing, only 13 of these 20 isolates showed the typical features (MLST and SCCmec types) of one or the other six pandemic clones. Furthermore, whereas these 13 isolates were indistinguishable by MLST and SCCmec type from one of the pandemic clones, the PFGE analysis of these isolates showed considerable differences (seven or more band differences) in SmaI DNA fragment patterns compared to the typical epidemic clones (results not shown). These differences may represent the genomic modifications related to the diminished capacity of the sporadic isolates for geographic spread (Table 1).

Combining ST and SCCmec types, the 41 isolates were classified into 24 clonal types, only 4 of which (including 13 isolates) were identical to one of the pandemic clones, indicating that MRSA isolates of very diverse genetic backgrounds are found not only in the community (26) but in hospitals as well. By using MLST and the algorithm BURST, the 41 clinical MRSA were classified into six CCs, with the exception of two clones that were considered singletons. Of the 24 clonal types, 17 were within the same CC as one of the pandemic MRSA clones, indicating that the majority of the sporadic isolates in our study probably evolved from one of the pandemic MRSA clones. Five of the remaining seven clonal types were only distantly related to epidemic MRSA clones, and their origins are not clear at the present time.

Evolution of sporadic MRSA.

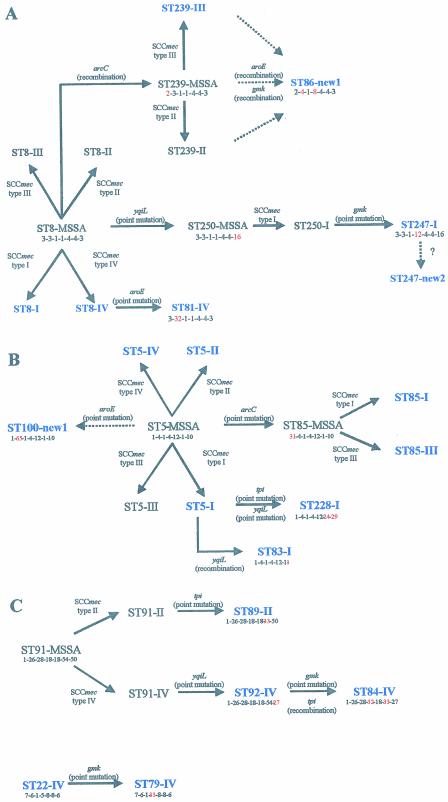

Figures 2 presents the putative evolutionary origins and patterns of descent of major STs identified among sporadic MRSA. Figure 2A shows the proposed relationships among the five STs (ST8, ST86, ST239, ST247, and ST81) within clonal type CC8 by the BURST analysis.

FIG. 2.

Evolutionary origins and patterns of descent within different CCs. Alterations in the allelic profile, the locus that has changed (in red), and the acquisition of the SCCmec types are shown. The STs present in our collection are in blue. Dashed arrows indicate unclear pathways. (A) Evolutionary origins and patterns of descent within CC8; (B) evolutionary origins and patterns of descent within CC5; (C) evolutionary origins and patterns of descent within CC91 and CC22.

Enright et al. (14) reported that ST8 was associated with the four types of SCCmec, and therefore ST8-MRSA clones could have emerged by multiple independent introductions of SCCmec into the successful ST8-MSSA clone (wherein MSSA refers to methicillin-susceptible S. aureus). In our study ST8 was associated with two SCCmec types (I and IV), a finding which supports the hypothesis of Enright et al. (14). These authors proposed that ST239, which is mainly associated with SCCmec III, was derived from ST8-III by an arcC recombination (14). ST239-II isolates were also found in other studies (14), which may indicate that ST239-MRSA clones emerged by independent introductions of mec into a ST239-MSSA, although isolates with this multilocus type had not yet been identified among susceptible S. aureus strains. ST86 is a double-locus variant (DLV) of ST239 differing in the aroE and gmk alleles. Clone ST86-new1 might have evolved from one of the ST239 clones after recombination in aroE and gmk. In the present study, ST247 was associated with two different SCCmec types: type I and type new2. SCCmec type new2 was found in two isolates from Argentina recovered in 1995 and 1996. Enright et al. (14) suggested that ST247-I evolved from ST250-I, which in turn evolved from ST8, the predicted ancestor of the corresponding CC (14). Our data suggests that ST247-new2 may have evolved from ST247-I by rearrangements in SCCmec, although we shall only be able to confirm this hypothesis after the entire sequence of this new SCCmec type is determined. ST81 differs from ST8 at the aroE locus and is probably derived from ST8 by a recent point mutation since the single-nucleotide difference in the aroE allele of ST81 (allele 32) is not found in any other aroE allele. In addition, ST81 has the same SCCmec type as ST8-IV.

Figure 2B shows the proposed relationships among the five STs (ST5, ST83, ST85, ST100, and ST228) distributed within the CC5 by the BURST analysis.

ST5 and ST85 were found associated with different SCCmec types, meaning that MRSA isolates of these STs have presumably arisen on different occasions. ST5, which is the predicted ancestor of CC5, is a very successful lineage, since it is represented by 95 isolates in the MLST database (20 of these are MSSA isolates). ST85 differs from ST5 at the arcC locus and is probably derived from ST5 since the single-nucleotide difference in the arcC allele of ST85 (allele 31) is not found in any other aroE allele and therefore must be a recent point mutation. ST83 has only been found in one isolate thus far and differs from ST5 at the yqiL allele (allele 1 instead of allele 10). We propose that ST83-I evolved from ST5-I that has the same SCCmec type by a yqiL recombination since this allele was found in many other STs and has two nucleotide differences in allele 10. ST228 is a DLV of ST5. The two isolates of ST228 found in the present study displayed SCCmec type I as had the other 13 isolates of this clone deposited in the MLST database. We propose that ST228-I evolved from ST5-I by recent point mutations in tpi and yqiL since tpi allele 24 and yqiL allele 29 were only found in ST228 and ST222. ST222 is an SLV of ST228 and, according to BURST, derived from ST228 (Fig. 1). ST100-new1 was determined to have evolved from ST5 by a recent aroE point mutation since this allele was found for the first time in the present study associated with ST100. We do not know the entire sequence of the SCCmec type new1, and therefore it was not possible to predict the origin of clone ST100-new1. It may have derived from ST5-MSSA or from any ST5-MRSA clone.

Figure 2C shows the proposed relationships among the three STs (ST84, ST89, and ST92) distributed within CC91 and also CC22 as determined by BURST analysis.

ST89 and ST92 may have evolved from ST91 since they are both SLVs of this ST, which was the predicted ancestor of the corresponding CC. ST89 differs from ST91 by a single-nucleotide difference in tpi, whereas ST92 differs from ST91 by a single-nucleotide difference in yqiL. ST89 and ST92 have different SCCmec types, which might signify that ST91-MRSA clones have emerged after two independent mec acquisitions. ST84 is a DLV of both ST89 and ST92. However, ST84-IV and ST92-IV have the same SCCmec type, which might indicate ST84-IV has evolved from ST92-IV after a gmk point mutation and a tpi recombination.

ST79 differs from ST22 at the gmk locus and is probably derived from ST22, which is a very common ST in the United Kingdom and Germany (14) and was the predicted ancestor of the corresponding CC. The single-nucleotide difference in the gmk allele of ST79 (allele 33) was not found in any other gmk allele and therefore must be a recent point mutation. In addition, ST79 and ST22 have the same SCCmec type IV.

CA-MRSA and sporadic hospital isolates of MRSA.

The genetically diverse community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) were reported to harbor preferentially SCCmec type IV (9, 16, 26). The sporadic MRSA isolates included in our study also had very diverse genetic backgrounds, and they carried most frequently either SCCmec type III (10 isolates) or IV (13 isolates). However, the 13 isolates that harbored SCCmec type IV were associated with as many as 11 different STs, whereas the 10 SCCmec type III isolates were associated with only 2 STs. Our data provide yet another line of evidence for the notion that the relatively small (21 to 25 kb) SCCmec type IV may have an increased mobility and therefore greater propensity for transfer to diverse S. aureus genetic backgrounds. The correlation between the size of the SCCmec and its facility of transfer is also consistent with the number of STs we found associated with each SCCmec type: the smaller the SCCmec the more STs were associated with it. For instance, SCCmec type IV was associated with 11 STs, type I was associated with 6 STs, and types II and III were associated with 2 STs only.

Most CA-MRSA isolates harboring SCCmec type IV appear to be resistant to β-lactam antibiotics only and have a heterogeneous methicillin resistance phenotype that is consistent with the lack of any antibiotic genes other than mecA in this type of mec cassette (22, 26, 29). In our studies, most MRSA isolates hraboring SCCmec type IV were resistant to fewer antibiotics than were isolates harboring the other SCCmec types. However, all SCCmec type IV isolates showed resistance to at least one additional antibiotic other than β-lactams, and 3 of 13 isolates were multiresistant (i.e., they were resistant to more than three antibiotic classes in addition to β-lactams) (Table 2). There was no clear correlation between the antibiogram and the SCCmec type. We suggest that some of the clinical MRSA isolates that harbored SCCmec type IV have acquired resistance to non-β-lactam antibiotics in order to be able to survive in the hospital environment, where the antibiotic selective pressure is high. However, the level of resistance is still not comparable to the multidrug resistance shown by most of the pandemic clones, which might partly explain the reduced capacity of these minor clones and sporadic isolates to spread in the hospital environment.

Besides the relatively simple antibiotic resistance profile, CA-MRSA strains displaying SCCmec type IV were also reported to show several additional differences from most hospital-acquired MRSA strains. CA-MRSA was reported to grow faster in vitro (26) and to carry additional virulence genes (6). In the present study, there was no clear correlation between growth rates and the particular structural types of SCCmec carried by the sporadic MRSA isolates. However, the observed mean growth rates for the 41 MRSA isolates (30.13 ± 5.20 min) were close to those reported by Okuma et al. (26) for CA-MRSA isolates (28.79 ± 7.09 min). Our findings suggest that a higher growth rate may be a prerequisite for minor MRSA clones and sporadic isolates to achieve successful colonization and infection by outcompeting the more epidemic MRSA clones present in the hospital and, perhaps, by compensating for the fewer drug resistance genes they carry.

PVL genes were reported to be strongly associated with primary skin infections and severe necrotizing pneumonia caused by some CA-MRSA strains, and these virulence genes were never detected in MRSA isolates associated with hospital-acquired infections (12). We recently documented the detection of PVL genes in SCCmec type IV MRSA isolates associated with hospital-acquired infection, suggesting that the presence of these genes is not an exclusive characteristic of CA-MRSA (1). One of these isolates (GRE14, ST80-SCCmec type IV [Table 2]) was included in the present study.

Our study documents several interesting similarities between CA-MRSA and sporadic MRSA isolates present in hospitals. Both CA-MRSA and the sporadic MRSA are genetically diverse, frequently carry SCCmec type IV, are susceptible to more antimicrobial agents and may contain the PVL genes. These observations raise the possibility that at least some of the MRSA strains described as community acquired may actually originate in hospitals. Because of their relatively limited antibiotic resistance, sporadic MRSA isolates have reduced capacity for spread and maintenance in the hospital environment which is dominated by the multidrug-resistant MRSA clones. After having “escaped” from the antibiotic-saturated hospital environment into the community, such a sporadic MRSA may be in an advantageous position since it is free of the biological cost of maintaining multidrug resistance mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by project POCTI/1999/ESP/34872 from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Portugal), project SDH.IC.I.01.13 from Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (Portugal) awarded to H. de Lencastre, and by U.S. Public Health Service National Institutes of Health grant R01 AI45738 awarded to A. Tomasz at The Rockefeller University. M. Aires de Sousa was supported by grant BD/13731/97 from PRAXIS XXI.

We thank M. I. Crisostomo for performing the spaA and MLST typing of nine MRSA isolates and M. C. Lopes for technical assistance on the doubling-time assays and the antimicrobial susceptibility testing. We are also grateful to D. Oliveira for helpful discussions concerning the SCCmec types, E. Feil for providing kind instruction on the BURST program, and A. Tomasz for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank R. Mato for sharing unpublished data on the Italian isolates. This publication made use of the MLST website (http://www.mlst.net), which is hosted at Imperial College London and at the University of Bath.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aires de Sousa, M., C. Bartzavali, I. Spiliopoulou, I. Santos Sanches, M. I. Crisóstomo, and H. de Lencastre. 2003. Two international methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones endemic in a university hospital in Patras, Greece. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2027-2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aires de Sousa, M., M. I. Crisóstomo, I. Santos Sanches, J. S. Wu, J. Fuzhong, A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2003. Frequent recovery of a single clonal type of multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from patients in two hospitals in Taiwan and China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:159-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aires de Sousa, M., H. de Lencastre, I. Santos Sanches, K. Kikuchi, K. Totsuka, and A. Tomasz. 2000. Similarity of antibiotic resistance patterns and molecular typing properties of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates widely spread in hospitals in New York City and in a hospital in Tokyo, Japan. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aires de Sousa, M., M. Miragaia, I. S. Sanches, S. Avila, I. Adamson, S. T. Casagrande, M. C. Brandileone, R. Palacio, L. Dell'Acqua, M. Hortal, T. Camou, A. Rossi, M. E. Velazquez-Meza, G. Echaniz-Aviles, F. Solorzano-Santos, I. Heitmann, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. Three-year assessment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Latin America from 1996 to 1998. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2197-2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amorim, M. L., M. Aires de Sousa, I. S. Sanches, R. Sá-Leão, J. M. Cabeda, J. M. Amorim, and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Clonal and antibiotic resistance profiles of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from a Portuguese hospital over time. Microb. Drug Resist. 8:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baba, T., F. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Yuzawa, K. Aoki, A. Oguchi, Y. Nagai, N. Iwama, K. Asano, T. Naimi, H. Kuroda, L. Cui, K. Yamamoto, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corso, A., I. Santos Sanches, M. Aires de Sousa, A. Rossi, and H. de Lencastre. 1998. Spread of a methicillin-resistant and multiresistant epidemic clone of Staphylococcus aureus in Argentina. Microb. Drug Resist. 4:277-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crisostomo, M. I., H. Westh, A. Tomasz, M. Chung, D. C. Oliveira, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. The evolution of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: similarity of genetic backgrounds in historically early methicillin-susceptible and -resistant isolates and contemporary epidemic clones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9865-9870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daum, R. S., T. Ito, K. Hiramatsu, F. Hussain, K. Mongkolrattanothai, M. Jamklang, and S. Boyle-Vavra. 2002. A novel methicillin-resistance cassette in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates of diverse genetic backgrounds. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1344-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lencastre, H., I. Couto, I. Santos, J. Melo-Cristino, A. Torres-Pereira, and A. Tomasz. 1994. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in a Portuguese hospital: characterization of clonal types by a combination of DNA typing methods. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lencastre, H., I. Santos Sanches, and A. Tomasz. 2000. CEM/NET: clinical microbiology and molecular biology in alliance, p. 451-456. In A. Tomasz (ed.), Streptococcus pneumoniae: molecular biology and mechanisms of disease. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., Larchmont, N.Y.

- 12.Dufour, P., Y. Gillet, M. Bes, G. Lina, F. Vandenesch, D. Floret, J. Etienne, and H. Richet. 2002. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in France: emergence of a single clone that produces Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:819-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enright, M. C., N. P. Day, C. E. Davies, S. J. Peacock, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enright, M. C., D. A. Robinson, G. Randle, E. J. Feil, H. Grundmann, and B. G. Spratt. 2002. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7687-7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feil, E. J., J. M. Smith, M. C. Enright, and B. Spratt. 2000. Estimating recombinational parameters in Streptococcus pneumoniae from multilocus sequence typing data. Genetics 154:1439-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fey, P. D., B. Said-Salim, M. E. Rupp, S. H. Hinrichs, D. J. Boxrud, C. C. Davis, B. N. Kreiswirth, and P. M. Schlievert. 2003. Comparative molecular analysis of community- or hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:196-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerhardt, P., R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg. 1994. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology, p. 270-271. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Gomes, A. R., I. S. Sanches, M. Aires de Sousa, E. Castaneda, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Colombian hospitals: dominance of a single unique multidrug-resistant clone. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, K. Asada, N. Mori, K. Tsutsumimoto, C. Tiensasitorn, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1323-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leski, T., D. Oliveira, K. Trzcinski, I. S. Sanches, M. A. de Sousa, W. Hryniewicz, and H. de Lencastre. 1998. Clonal distribution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Poland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3532-3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lina, G., Y. Piemont, F. Godail-Gamot, M. Bes, M. O. Peter, V. Gauduchon, F. Vandenesch, and J. Etienne. 1999. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:1128-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma, X. X., T. Ito, C. Tiensasitorn, M. Jamklang, P. Chongtrakool, S. Boyle-Vavra, R. S. Daum, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Novel type of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec identified in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1147-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melter, O., I. Santos Sanches, J. Schindler, M. Aires de Sousa, R. Mato, V. Kovarova, H. Zemlickova, and H. de Lencastre. 1999. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonal types in the Czech Republic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2798-2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 25.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1999. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 26.Okuma, K., K. Iwakawa, J. D. Turnidge, W. B. Grubb, J. M. Bell, F. G. O'Brien, G. W. Coombs, J. W. Pearman, F. C. Tenover, M. Kapi, C. Tiensasitorn, T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Dissemination of new methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in the community. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4289-4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira, D. C., I. Crisostomo, I. Santos-Sanches, P. Major, C. R. Alves, M. Aires-de-Sousa, M. K. Thege, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. Comparison of DNA sequencing of the protein A gene polymorphic region with other molecular typing techniques for typing two epidemiologically diverse collections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:574-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira, D. C., and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2155-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveira, D. C., A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. The evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: identification of two ancestral genetic backgrounds and the associated mec elements. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:349-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliveira, D. C., A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Secrets of success of a human pathogen: molecular evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos Sanches, I., R. Mato, H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 2000. Patterns of multidrug resistance among methicillin-resistant hospital isolates of coagulase-positive and coagulase-negative staphylococci collected in the international multicenter study RESIST in 1997 and 1998. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:199-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shopsin, B., M. Gomez, S. O. Montgomery, D. H. Smith, M. Waddington, D. E. Dodge, D. A. Bost, M. Riehman, S. Naidich, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1999. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3556-3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomasz, A., and H. de Lencastre. 1997. Molecular microbiology and epidemiology: coexistence or alliance?, p. 309-322. In R. P. Wenzel (ed.), Prevention and control of nosocomial infections. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.