Abstract

Grass weed populations resistant to aryloxyphenoxypropionate (APP) and cyclohexanedione herbicides that inhibit acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase; EC 6.4.1.2) represent a major problem for sustainable agriculture. We investigated the molecular basis of resistance to ACCase-inhibiting herbicides for nine wild oat (Avena sterilis ssp. ludoviciana Durieu) populations from the northern grain-growing region of Australia. Five amino acid substitutions in plastid ACCase were correlated with herbicide resistance: Ile-1,781-Leu, Trp-1,999-Cys, Trp-2,027-Cys, Ile-2,041-Asn, and Asp-2,078-Gly (numbered according to the Alopecurus myosuroides plastid ACCase). An allele-specific PCR test was designed to determine the prevalence of these five mutations in wild oat populations suspected of harboring ACCase-related resistance with the result that, in most but not all cases, plant resistance was correlated with one (and only one) of the five mutations. We then showed, using a yeast gene-replacement system, that these single-site mutations also confer herbicide resistance to wheat plastid ACCase: Ile-1,781-Leu and Asp-2,078-Gly confer resistance to APPs and cyclohexanediones, Trp-2,027-Cys and Ile-2,041-Asn confer resistance to APPs, and Trp-1,999-Cys confers resistance only to fenoxaprop. These mutations are very likely to confer resistance to any grass weed species under selection imposed by the extensive agricultural use of the herbicides.

Keywords: aryloxyphenoxypropionate, Avena, cyclohexanedione

Aryloxyphenoxypropionates (APPs) and the cyclohexanediones (CHDs) are often used to control grass weeds selectively. These herbicides target the fatty acid biosynthetic pathway of grasses by inhibiting the plastid form of the enzyme acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase; EC 6.4.1.2). However, many weed populations have become resistant to APPs and CHDs, including some of the major grass weeds, such as wild oat (Avena fatua L. and Avena sterilis ssp. ludoviciana Durieu), rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaudin), black grass (Alopecurus myosuroides Hudson), and green foxtail (Setaria viridis L. Beauv) (1). Here we describe the distribution of mutations conferring resistance to these herbicides in several wild oat populations in the northern wheat-growing areas of Australia.

In both eukaryotes and prokaryotes, ACCase is a biotinylated enzyme that catalyzes the first committed step of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis by carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-Co in a two-step reaction: carboxylation of the biotin group of the enzyme, followed by transfer of the carboxyl group from carboxybiotin to acetyl-CoA by the carboxyltransferase (CT) activity. In plants, ACCase activity is found in both plastids where primary fatty acid biosynthesis occurs and the cytosol where synthesis of very long-chain fatty acids and flavonoids occurs. Selectivity of APP and CHD herbicides is due to the different types of plastid ACCase found in plants. The multidomain type found in the cytosol of all plants and the multisubunit type found in plastids of dicots are insensitive to APPs and CHDs. In contrast, the plastid ACCase in grasses is herbicide-sensitive. Expression of the latter is high in the meristematic region of young plants (2), reflecting the demand for malonyl-CoA in dividing and fast-growing cells and consistent with the high efficacy of postemergence application of the herbicides. APP and CHD herbicides interact with the CT domain of ACCase (3). The APP-binding site has been inferred from the 3D structure of the CT domain of yeast ACCase complexed with haloxyfop (4).

Five amino acid substitutions in the CT domain have been implicated in resistance to APP and/or CHD herbicides: an Ile-1,781-Leu substitution in A. myosuroides (5–7) as well as homologous substitutions in L. rigidum (8, 9), S. viridis (10), A. fatua (11), and Lolium multiflorum (12); an Ile-2,041-Asn substitution in A. myosuroides as well as homologous substitution in L. rigidum (13); and Trp-2,027-Cys, Gly-2,096-Ala, and Asp-2,078-Gly substitutions in A. myosuroides (14). Ile-1,781-Leu and Asp-2,078-Gly mutations are correlated with resistance to APPs and CHDs, whereas Trp-2,027-Cys, Ile-2,041-Asn, and Gly-2,096-Ala are correlated with resistance to APPs but not CHDs. Knowledge of the molecular basis of resistance to ACCase-inhibitors caused by mutations in the enzyme is based primarily on characterization of the diploid weed species A. myosuroides and L. rigidum. It was also shown that a single amino acid change in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plastid ACCase, corresponding to the Ile-1,781-Leu substitution, makes the enzyme resistant to APPs and CHDs (8). Other mechanisms of resistance to APPs and CHDs have been proposed, for example, rapid herbicide detoxification (reviewed in ref. 1). In this study, we identify ACCase mutations in nine populations of hexaploid wild oat A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana, a major weed in winter crops in North America and the northern grain-growing region of Australia. We show that each of these single-site mutations affects herbicide sensitivity of the susceptible ACCase. A simple PCR-based test makes it possible to determine herbicide sensitivity of A. sterilis weeds rapidly.

Results

Four amino acid substitutions in the CT domain of ACCase from herbicide-resistant A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana plants were identified by sequencing genomic DNA and cDNA: Trp-1,999-Cys (TGG to TGT) in the Shk population; Trp-2,027-Cys (TGG to TGT) in the Nx99 population; Ile-2,041-Asn (ATT to AAT) in the UQT population; and Asp-2,078-Gly (GAT to GGT) in the UQM population (Fig. 1 and Table 1). We confirmed that these amino acid changes are sufficient to alter wild oat ACCase sensitivity to herbicides by using yeast gene-replacement strains containing wheat ACCase (see below). These changes account for the resistant phenotype of plants in the A. sterilis populations. Our findings are consistent with other studies described in the Introduction, except for the Trp-1,999-Cys substitution, which has not been implicated previously in resistance of any species. Genomic DNA and cDNA sequences were consistent, indicating that all of the mutant alleles were transcribed, a necessary step for the expression of the resistant phenotype. Partial sequence comparisons with the three homoeologous sequences of the wild-type (susceptible) A. fatua revealed that Trp-1,999-Cys, Ile-2,041-Asn, and Asp-2,078-Gly are located each in the three ACC homoeologous genes of the hexaploid A. sterilis genome. Trp-2,027-Cys could not be assigned to any particular homoeolog because of the lack of polymorphism in the sequenced fragment.

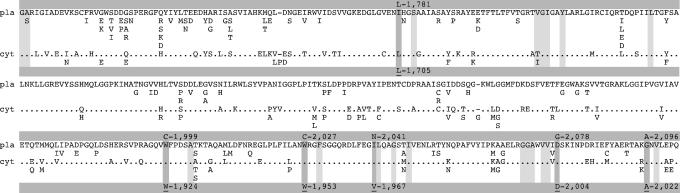

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence comparisons of the herbicide target site in the CT domain of the plant plastid (pla) and cytosolic (cyt) multidomain ACCase. Mutations associated with resistance are shown with residue numbering following the full-length A. myosuroides plastid ACCase (GenBank accession no. AJ310767) highlighted by dark-gray vertical strips with amino acids found at the corresponding position in yeast shown in the bottom row (underlined with numbering following the yeast ACCase sequence). Amino acid residues implicated in APP binding (5) are highlighted by light-gray vertical strips. Dots indicate identical residues. The composite sequences of the plastid and cytosolic ACCase were derived from sequences available from GenBank in December 2006.

Table 1.

Herbicide sensitivity and ACCase mutations in individual resistant plants of nine populations of A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana suspected of carrying herbicide resistance

| Population | Number of plants |

Mutation in resistant plants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APP* |

CHD |

||||||||||

| Fenoxaprop |

Clodinafop |

Haloxyfop |

Sethoxydim |

Tralkoxydim |

|||||||

| R | S | R | S | R | S | R | R | R | S | ||

| Shk | 28 | 2 | W-1,999-Cb,c | ||||||||

| 11 | D-2,078-Gc | ||||||||||

| 1 | I-2,041-Nc | ||||||||||

| 8 | none detected | ||||||||||

| Nx99 | 28 | 22 | W-2,027-Cb,c | ||||||||

| UQT | 30 | 0 | 2 | 28 | I-2,041-Nb,c | ||||||

| UQM | 29 | 1 | 26 | 4 | D-2,078-Gb,c | ||||||

| McdNl | 20 | 0 | 14 | 6 | Leu-1,781c | ||||||

| McdLed | 20 | 0 | 14 | 6 | D-2,078-Gc | ||||||

| Crooble | 20 | 0 | 4 | 16 | D-2,078-Gc | ||||||

| Nx03 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 10 | W-2,027-Cc | ||||||

| Ew | 1 | 14 | 1 | 10 | W-2,027-Cc | ||||||

| 1 | 5 | none detected | |||||||||

R, resistant plants; S, susceptible plants.

*Applied in form of esters.

†Detected by DNA sequencing.

‡Detected by allele-specific PCR.

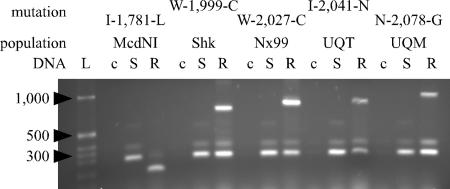

Allele-specific PCR tests developed for each of the five mutations implicated in herbicide resistance (Fig. 2), including the Ile-1,781-Leu substitution previously identified in other grass species, were used to screen all of the individual plants of the Nx99, UQT, UQM, and Shk populations, which survived herbicide treatment (Table 1). As expected, all 28 plants from the Nx99 population that survived the APP treatment contained the Cys-2,027 allele; all 30 UQT plants surviving the APP herbicide treatment, as well as two plants surviving the CHD herbicide treatment, contained the Asn-2,041 allele; and all 29 UQM plants surviving the APP herbicide treatment, as well as 26 plants surviving the CHD herbicide treatment, contained the Gly-2,078 allele. The control-susceptible biotype did not contain these alleles. These correlations confirmed our conclusion from the initial sequencing experiment.

Fig. 2.

Allele-specific PCR tests for ACCase mutations in herbicide-resistant populations of A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana. L, 1-kb DNA marker; c, no DNA control; S, template DNA from a susceptible plant; R, template DNA from a resistant plant from each of the populations.

In the Shk population, among the 48 individuals surviving the fenoxaprop treatments, 28 contained the Cys-1,999 allele, 11 contained the Gly-2,078 allele, and one contained the Asn-2,041 allele (Table 1). There were eight individuals in the Shk population that survived fenoxaprop treatment but carried none of the five mutations.

The allele-specific PCR test was then used to screen five additional resistant populations (Table 1). For population McdNl, all 20 clodinafop-resistant and all 14 tralkoxydim-resistant plants contained the Leu-1,781 allele. For population McdLed, all 20 haloxyfop- and all 14 tralkoxydim-resistant plants contained the Gly-2,078 allele. For population Crooble, all 20 fenoxaprop- and all four sethoxydim-resistant plants contained the Gly-2,078 allele. For population Nx03, all 20 clodinafop- plants and all 10 tralkoxydim-resistant plants contained the Cys-2,027 allele. For population Ew, only one of the two clodinafop- and one of the six tralkoxydim-resistant plants contained the Cys-2,027 allele. None of the mutations assessed in this study was detected in the remaining six ACCase-inhibitor-resistant EW plants.

Two hundred seventy-nine plants from nine populations each carried only one of the five ACCase mutations associated with resistance. Plants from population Shk carrying mutant alleles Cys-1,999 and Gly-2,078 and plants from population Nx99 carrying the Cys-2,027 allele survived fenoxaprop treatment at doses 2–16 times the recommended rate of application. On the contrary, the Asn-2,041 allele was never found in plants that survived the treatment at higher doses, suggesting a lower level of resistance for this allele.

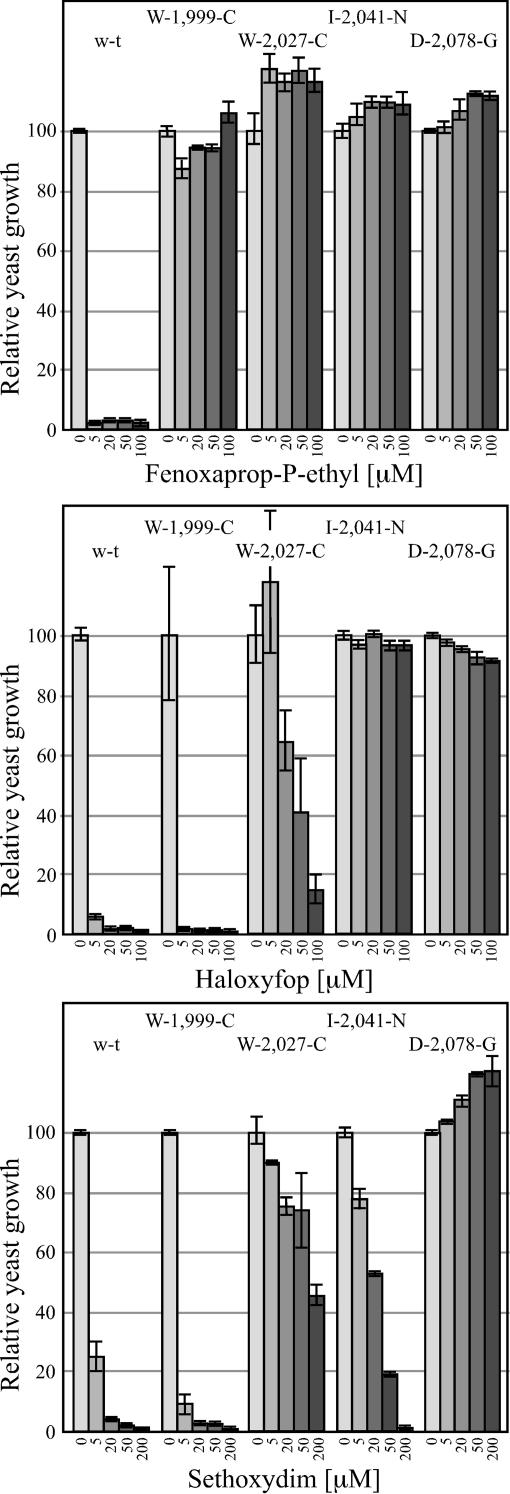

Four yeast gene-replacement strains depending for growth on a chimeric wheat ACCase, each carrying a single mutation associated with herbicide resistance, were tested. The chimeric ACCase consisted of the N-terminal half of the wheat cytosolic ACCase and C-terminal half of the wheat plastid ACCase, including the entire herbicide-binding domain shown in Fig. 1. We showed previously that such chimeric ACCase complements the yeast ACC1 null mutation, and that growth inhibition of the resulting yeast gene-replacement strain reflects sensitivity of the wheat plastid ACCase to inhibitors (3, 8). We further showed that a single amino acid change corresponding to the Ile-1,781-Leu mutation makes the yeast strain resistant to CHDs (sethoxydim) and APPs (haloxyfop) (8). Wild-type yeast is resistant to both APPs and CHDs (3, 15). Yeast with chimeric ACCases carrying Trp-2,027-Cys, Ile-2,041-Asn, and Asp-2,078-Gly mutations grow as well as the strain with the wild-type residues. A strain with the Trp-1,999-Cys mutation grows significantly slower (2-fold longer doubling time). Chimeric ACCase with the Gly-2,096-Ala mutation did not complement the yeast ACC1 null mutation, presumably due to lack of enzymatic activity sufficient to sustain yeast growth.

The Trp-1,999-Cys mutation renders the yeast gene-replacement strain resistant to fenoxaprop only but has no effect on sensitivity to haloxyfop and sethoxydim (Fig. 3) and clodinafop (data not shown). This mutation was found in some plants of the Shk population resistant to fenoxaprop but not in populations resistant to other APPs or CHDs (Table 1). The Trp-2,027-Cys, Ile-2,041-Asn, and Asp-2,078-Gly mutations render the strains resistant to fenoxaprop, haloxyfop, and clodinafop (Fig. 3 and data not shown). The effect of the Trp-2,027-Cys mutation on sensitivity to haloxyfop and clodinafop is not as strong as that of the other two mutations and not as strong as its effect on sensitivity to fenoxaprop. The Asp-2,078-Gly mutation causes complete resistance to sethoxydim, but only partial sethoxydim resistance was observed for Trp-2,027-Cys and Ile-2,041-Asn (Fig. 3). In the latter case, the partial resistance was observed only in some experiments, suggesting that the effect of these mutations is rather small leading to the variable result, depending, for example, on the yeast growth conditions. We have observed such variability in other experiments using the yeast gene-replacement system. Most plants of the UQM, McdLed, and Crooble populations are resistant to both APPs and CHDs, and they carry the Asp-2,078-Gly mutation, whereas only a smaller number of plants from populations UQT and Nx03, which are consistently resistant to APPs and carry the Ile-2,041-Asn and Trp-2,027-Cys mutation, respectively, are resistant to CHDs. Thus, the results of the yeast experiments are fully consistent with the results of the whole plant phenotypic assays.

Fig. 3.

Response of yeast gene-replacement strains that depends for growth on chimeric wheat ACCase carrying single-site mutations to fenoxaprop-P-ethyl, haloxyfop, and sethoxydim. The control (sensitive) strain (w-t) with wild-type chimeric wheat ACCase was described previously (4).

Haloxyfop-methyl ester and clodinafop-propargyl ester were compared with haloxyfop and clodinafop in the yeast system (data not shown). We found no significant difference between inhibitory properties of APP free acids and their esters, suggesting that yeast can hydrolyze the esters efficiently to provide the APPs in the active form as free acids.

Discussion

Wild oats (A. fatua and A. sterilis) occur throughout all of Australia's cereal-growing regions. A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana is the predominant weed in the northern grain region of Australia, particularly prevalent in cropping systems with winter cereals, primarily wheat, and winter pulse rotation. It has been successfully controlled by postemergence application of APPs and CHDs. The excellent efficacy of these herbicides, which do not affect broadleaf crops (insensitive ACCase), as well as some cereals, such as wheat (rapid herbicide detoxification), on many grass weed species encouraged their widespread and repeated use. Thirty-five resistant species have been reported in 26 countries (the first case in 1982) with increasing numbers of sites and areas of infestation, and nine resistant species in Australia, including the first case of resistance in wild oat in Western Australia in 1985. Twelve randomly collected A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana samples from in-crop sites and fallow paddocks in the northern grain region of Australia in the winter of 2002 were tested in this study for herbicide resistance. All were sensitive, suggesting that the herbicide resistance is not yet widespread. However, plants from nine populations from the same region supplied by farmers as suspected to be resistant to ACCase herbicides, based on poor weed control in the field, all showed a high level of resistance in subsequent pot tests, either to APPs or CHDs or both (Table 1). The herbicide-use history for the populations is incomplete, but the available data indicate at least 2 years of herbicide application at all nine sites. For example, population Nx03 was subjected to four APP treatments [fenoxaprop (1996), clodinafop (1997), haloxyfop (1998), and haloxyfop (2001)], followed by two CHD treatments [sethoxydim (2002) and clethodim (2003)].

Using a combination of DNA sequencing and allele-specific PCR, we identified five amino acid substitutions in the plastid ACCase gene of nine A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana populations resistant to ACCase-inhibiting herbicides (Table 1 and Fig. 1). All of these mutations cluster in the CT domain, which contains the binding site of APP and CHD herbicides (3, 4, 8). These mutated amino acid residues are not found at corresponding ACCase positions in any susceptible grass species. Furthermore, four of these mutations, Ile-1,781-Leu, Trp-2,027-Cys, Ile-2,041-Asn, and Asp-2,078-Gly, have been reported in other ACCase-inhibitor resistant grass weed species (5–14), mostly in A. myosuroides. The Trp-1,999-Cys mutation has not been previously described in any herbicide-susceptible grass. We have also identified the Gly-2,078 allele in resistant L. rigidum (unpublished data), which further supports involvement of this substitution in herbicide resistance in different plants. The presence of any one of these mutations in plastid ACCase is correlated with plant resistance to the herbicides, suggesting strongly that the lost sensitivity of the enzyme to the inhibitors is responsible for the resistant phenotype of the plant.

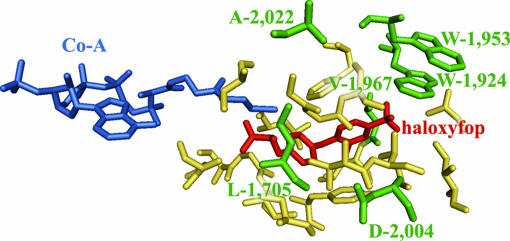

The 400-aa domain shown in Fig. 1 contains all of the residues shown to be present in the APP-binding pocket as well as residues of the CoA-binding site (4, 16). In the 3D structure of the CT domain from yeast ACCase, the two sites are very close to each other but do not overlap. The six herbicide-resistant mutations are located in this domain: I-1,781-L (yeast L-1,705), W-1,999-C (yeast W-1,924), I-2,041- (yeast V-1,967), D-2,078-G (yeast D-2,004) in the immediate vicinity of bound inhibitor, and W-2,027-C (yeast W-1,953) and G-2,096-A (yeast A-2,022), a short distance away (Fig. 4). The multidomain plastid ACCase gene in grasses originated by duplication of the cytosolic gene early during evolution of the grass/monocot lineage (17), a relationship reflected in their high sequence similarity (Fig. 1). All but one of the residues involved in APP binding and resistance are conserved in both ACCase isozymes in grasses as well as all cytosolic ACCases from dicot plants, the next closest group of relatives of the grass ACCases (not shown). I-1,781-L is the only amino acid difference consistent with the resistance of all plant cytosolic ACCases to APPs and CHDs. However, pea and corn cytosolic ACCase are somewhat sensitive to APPs (18). Furthermore, the Toxoplasma gondii apicoplast ACCase, which is sensitive to APPs, although less than the plastid ACCase from grasses (8, 19, 20), has all of the critical residues identified in Fig. 1, except for L-1,781 and S-2,073, but changing the Leu to Ile in this context reduces sensitivity to APPs.

Fig. 4.

Position of amino acid residues corresponding to the six herbicide-resistance mutations (green) in the 3D structure of the CT domain of yeast ACCase in complex with CoA (blue) and haloxyfop (red) (5, 17). Amino acids shown in yellow were determined to contribute to the haloxyfop-binding site (5). This illustration was prepared by using PyMol (DeLano Scientific, South San Francisco, CA) and coordinates from Protein Data Bank ID codes 1UYS and 1OD2. The numbering follows the yeast ACCase sequence.

Consistent with previous studies on other grassy weeds, including L. rigidum, A. myosuroides, S. viridis, and A. fatua (5–12), the Leu-1,781 allele was found in the McdLed population resistant to both APP and CHD herbicides. Also consistent with the study on A. myosuroides by Delye et al. (14), the Gly-2,078 allele was detected in UQM, McdLed, and Crooble populations resistant to both APPs and CHDs (Table 1). The Asn-2,041 allele was found in UQT populations resistant to APP but sensitive to CHD herbicides, which again concurs with previous studies on A. myosuroides and L. rigidum (13). However, two plants from this population carrying the Asn-2,041 allele survived sethoxydim treatment, which is unexpected. These plants might carry the Gly-2,096-Ala substitution, which was not assayed in this study but was found to confer resistance to APPs in A. myosuroides (14) or a previously undescribed resistance allele in ACCase. The Gly-2,096-Ala substitution, which was not found in any of the A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana populations investigated in the initial sequence-based analysis, could explain the eight Shk and one Ew plants resistant to APPs (and not containing any of the other known resistance alleles), but it does not explain the five EW and two UQT plants resistant to CHDs. Other resistance mechanisms such as enhanced metabolism could also be at play, as previously proposed (reviewed in ref. 1). Ten plants from the Nx03 population, which were resistant to the CHD, tralkoxydim, contained the Cys-2,027 allele, which was reported to confer resistance to APPs only (14). However, this particular CHD has not been studied previously in relation to the Cys-2,027 allele.

Sequence comparisons of the Cys-1,999, Cys-2,027, Asn-2,041, and Gly-2,078 alleles with the three ACC1 homoelogs of A. fatua demonstrated that any of the three homoelogs in hexaploid A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana can harbor the herbicide-resistance mutations. Therefore, the chance of hexaploid wild oats accumulating a mutated allele is greater than that of diploid grass weeds. Crossing plants containing the different resistance alleles to produce progeny containing resistance mutations on each of the homoeologous chromosomes could prove useful to investigation of the contribution of gene dosage to differing resistance levels in polyploid weed species. Interestingly, one population (Shk) in this study contained at least three different resistance mutations, but no individual plant contained more than one mutation. It is possible that a fitness penalty may be associated with multiple mutations.

Our experiments using yeast gene-replacement strains confirm the results from the phenotypic and sequence analysis: single amino acid changes Ile-1,781-Leu and Asp-2,078-Gly confer strong resistance to both APPs and CHDs; Trp-2,027-Cys and Ile-2,041-Asn confer strong resistance to APPs (and mild resistance to CHDs), and Trp-1,999-Cys confers strong resistance to only one of the tested APPs, fenoxaprop. These amino acid substitutions are correlated with resistance in plants such as A. sterilis, A. myosuroides, and L. rigidum but also work in the structural context of the wheat plastid ACCase, suggesting that such single-amino acid mutant alleles can easily be selected in other grassy weeds subjected to herbicide treatment.

The slow growth of the gene-replacement strain with the Trp-1,999-Cys ACCase mutant suggests this mutation has a significant effect on the enzymatic activity. Such a decreased activity could impose a significant fitness penalty on a plant carrying the mutant allele affecting its persistence in wild populations once the selective pressure is removed. The effect on fitness of hexaploid plants, such as wild oats, could be less severe. Decreased enzymatic activity was suggested for ACCases with the Trp-2,027-Cys and Asp-2,078-Gly mutations but not the Ile-2,041-Asn and G-2,096-A mutations (13, 14). In this context, lack of complementation by ACCase with the G-2,096-A mutation must be due to a specific problem in the structural context of wheat plastid ACCase. Wild-type yeast ACCase has an Ala residue at the corresponding position, and therefore this residue by itself is not deleterious.

Using the allele-specific PCR tests developed in this study, five resistant populations were quickly confirmed to contain mutations in ACCase, in addition to the four populations confirmed by more extensive DNA sequencing. Molecular-based diagnostic methods have the advantage of quickly detecting resistant plants compared with conducting pot assays, which are time- and space-consuming and labor-intensive. Reliable, fast, simple detection of herbicide resistance is necessary for farmers to adopt timely alternative herbicide application strategies to prevent further spread of herbicide-resistant weeds. However, only the phenotypic assays can identify individuals with resistance mechanisms that have not yet been characterized at the molecular level.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Herbicide Treatment.

Herbicide resistance of nine A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana populations (Table 1) from the northern grain region of Australia (Southern Queensland and Northern New South Wales) was confirmed by pot assay by using the same herbicide(s) that failed in the field. Seedlings at the three- to four-leaf stage (five per pot) were sprayed with herbicides in a wind tunnel using a traversing boom spray operated at a height of 70 cm above the plants, with flat fan nozzles and a spray pressure of 0.3 MPa. Herbicides were applied at the manufacturer's recommended field application rate: 0.3 liter·ha−1 fenoxaprop-P-ethyl [110 g active ingredient (a.i.) liter−1]; 0.125 liter·ha−1 clodinafop-propargyl (240 g of a.i. liter−1); 0.3 liter·ha−1 haloxyfop (130 g of a.i. liter−1); 1.0 liter·ha−1 sethoxydim (186 g of a.i. liter−1), and 500 g·ha−1 tralkoxydim (400 g of a.i. kg−1). APP treatments included nonionic surfactant Agral (0.25% vol/vol), and CHD treatments included 1.0 liter·ha−1 adjuvant oil D-C-TRATE, (763 g·liter−1). Shk and Nx99 populations were also treated with doses 2, 4, 8, and 16 times the recommended rate. Plants were monitored daily and assessed visually at 30 days after treatment to be resistant (alive) or susceptible (dead). Twelve random A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana populations from the same region of Australia tested under the same regime were herbicide-sensitive.

Sequencing of the Plastid ACCase CT Domain and Allele-Specific PCR.

Total DNA and RNA were extracted from leaf tissue from a single plant. RNA extracted using TRIzol method (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) and treated with DNase (Promega, Madison, WI) was used as a template to synthesize single-stranded cDNA with a polydT primer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Universal PCR primers [supporting information (SI) Table 2] for amplification of all homoeologous DNA fragments encoding part of the CT domain of the plastid ACCase of A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana were designed based on DNA sequences of A. fatua (GenBank accession nos. AF231334, AF231335, AF231336, AF231337, AF464875, and AF464876) and L. rigidum (GenBank accession nos. AF359513, AF359514, AF359515, and AF359516). Allele-specific primers used for PCR detection of mutants are shown in SI Table 2. The PCR primers were also used for sequencing (see SI Materials and Methods). The allele-specific PCR test was used to screen all of the resistant A. sterilis ssp. ludoviciana plants identified in this study for the presence or absence of the respective mutations. Amino acid numbering for A. sterilis follows the full-length A. myosuroides plastid ACCase (GenBank accession no. AJ310767).

Herbicides.

Sethoxydim (Bayer Cropscience Australia, East Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia; Crescent Chemicals, Hauppauge, NY; or Sigma-Aldrich, Castle Hill NSW, Australia), tralkoxydim (Crop Care Australasia, Murrarie, Queensland, Australia), fenoxaprop-P-ethyl (Bayer Cropscience Australia or Sigma-Aldrich), clodinafop-propargyl plus clodinafop-cloquintocet-methyl (Syngenta Crop Protection, North Ryde NSW, Australia), haloxyfop-R-methyl ester (Nufarm Australia, Laverton, Victoria, Australia), haloxyfop (Crescent Chemicals, or Sigma-Aldrich), clodinafop (Syngenta, Research Triangle Park, NC), agral (Syngenta Crop Protection, North Ryde NSW, Australia), D-C-TRATE (Caltex Australia Petroleum, Sydney NSW, Australia).

Yeast Gene-Replacement Strains.

Single amino acid substitutions in the CT domain in wheat plastid ACCase were introduced by replacing a 1.6-kb BlpI-ApaI fragment in construct C50P50 in vector pRS423 (4) with the corresponding mutated fragment prepared by two-step PCR procedure. Structures of the new constructs was verified by DNA sequencing. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain W303D-ACC1ΔLeu-2 (ACC1/acc1::LEU2) used for complementation was provided by S. Kohlwein (Technical University, Graz, Austria). Yeast transformation, sporulation, tetrad analysis, marker- and galactose-dependence tests, yeast growth, and inhibition measurements were carried out as described (3, 15). Yeast growth experiments were carried out by using either 3-ml cultures in tubes or 0.2-ml cultures in 96-well culture plates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Y. Lee (University of Chicago, Chicago, IL) for technical assistance. We also thank the Centre for Pesticide Application and Safety, University of Queensland, Gatton, for providing assistance with herbicide application and access to the wind tunnel facility. This research was supported by the Australian Grains Research and Development Corporation and the University of Queensland.

Abbreviations

- APP

aryloxyphenoxypropionate

- CHD

cyclohexanedione

- ACCase

acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- CT

carboxyltransferase.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0611572104/DC1.

References

- 1.Delye C. Weed Sci. 2005;53:728–746. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podkowinski J, Jelenska J, Sirikhachornkit A, Zuther E, Haselkorn R, Gornicki P. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:763–772. doi: 10.1104/pp.013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikolskaya T, Zagnitko O, Tevzadze G, Haselkorn R, Gornicki P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14647–14651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Tweel B, Tong L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5910–5915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400891101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown AC, Moss SR, Wilson ZA, Field LM. Pest Biochem Physiol. 2002;72:160–168. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delye C, Calmes E, Matejicek A. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;104:1114–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00122-001-0852-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delye C, Matejicek A, Gasquez J. Pest Manag Sci. 2002;58:474–478. doi: 10.1002/ps.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zagnitko O, Jelenska J, Tevzadze G, Haselkorn R, Gornicki P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6617–6622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121172798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang XQ, Powles SB. Planta. 2006;223:550–557. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delye C, Wang TY, Darmency H. Planta. 2002;214:421–427. doi: 10.1007/s004250100633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christoffers MJ, Berg ML, Messersmith CG. Genome. 2002;45:1049–1056. doi: 10.1139/g02-080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White GM, Moss SR, Karp A. Weed Res. 2005;45:440–448. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delye C, Zhang XQ, Chalopin C, Michel S, Powles SB. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1716–1723. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delye C, Zhang XQ, Michel S, Matejicek A, Powles SB. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:794–806. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joachimiak M, Tevzadze G, Podkowinski J, Haselkorn R, Gornicki P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9990–9995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong L, Harwood HJ., Jr J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:1476–1488. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang SX, Sirikhachornkit A, Faris JD, Su XJ, Gill BS, Haselkorn R, Gornicki P. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48:805–820. doi: 10.1023/a:1014868320552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbert D, Price LJ, Alban C, Dehaye L, Job D, Cole DJ, Pallett KE, Harwood JL. Biochem J. 1996;318:997–1006. doi: 10.1042/bj3180997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jelenska J, Sirikhachornkit A, Haselkorn R, Gornicki P. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23208–23215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200455200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuther E, Johnson JJ, Haselkorn R, McLeod R, Gornicki P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13387–13392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.