Abstract

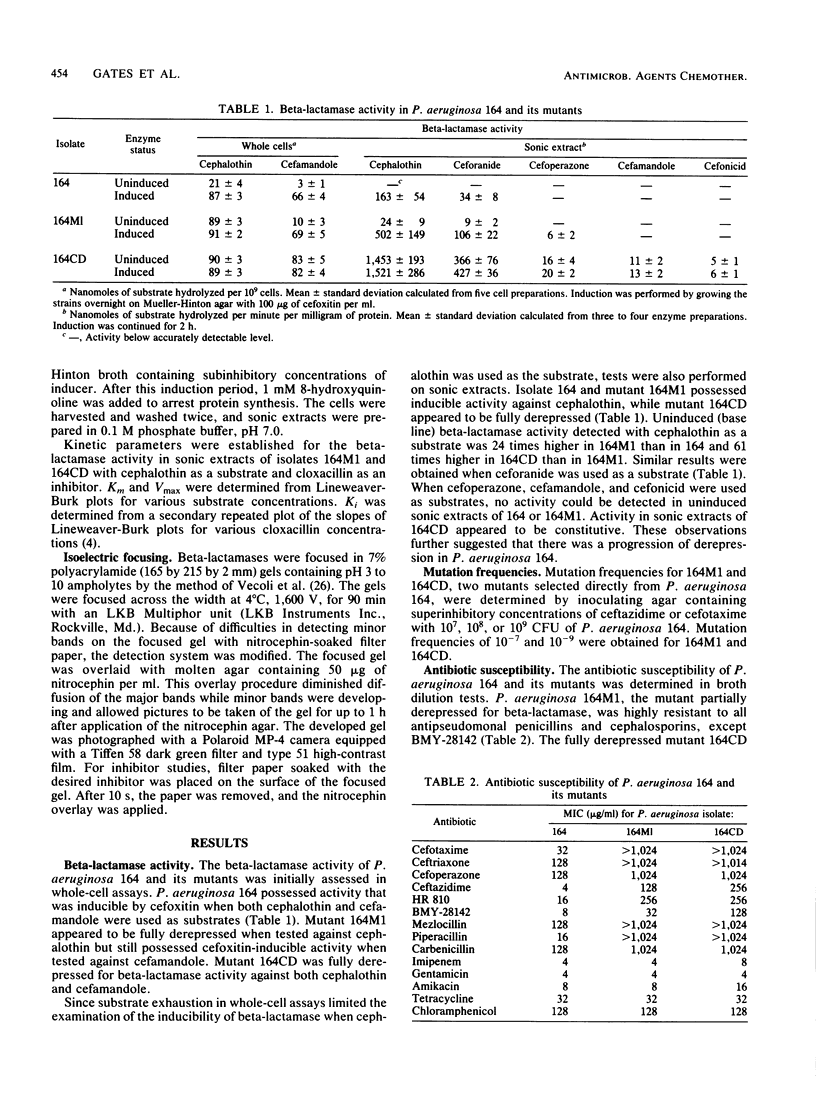

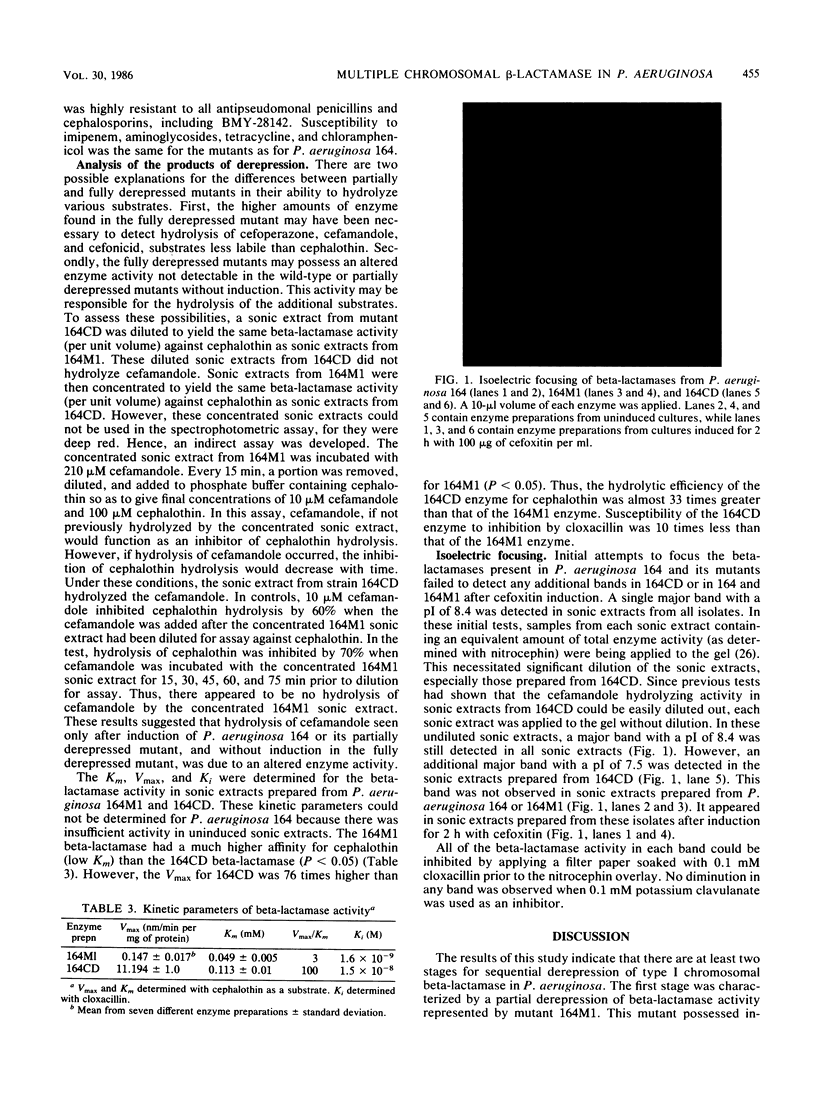

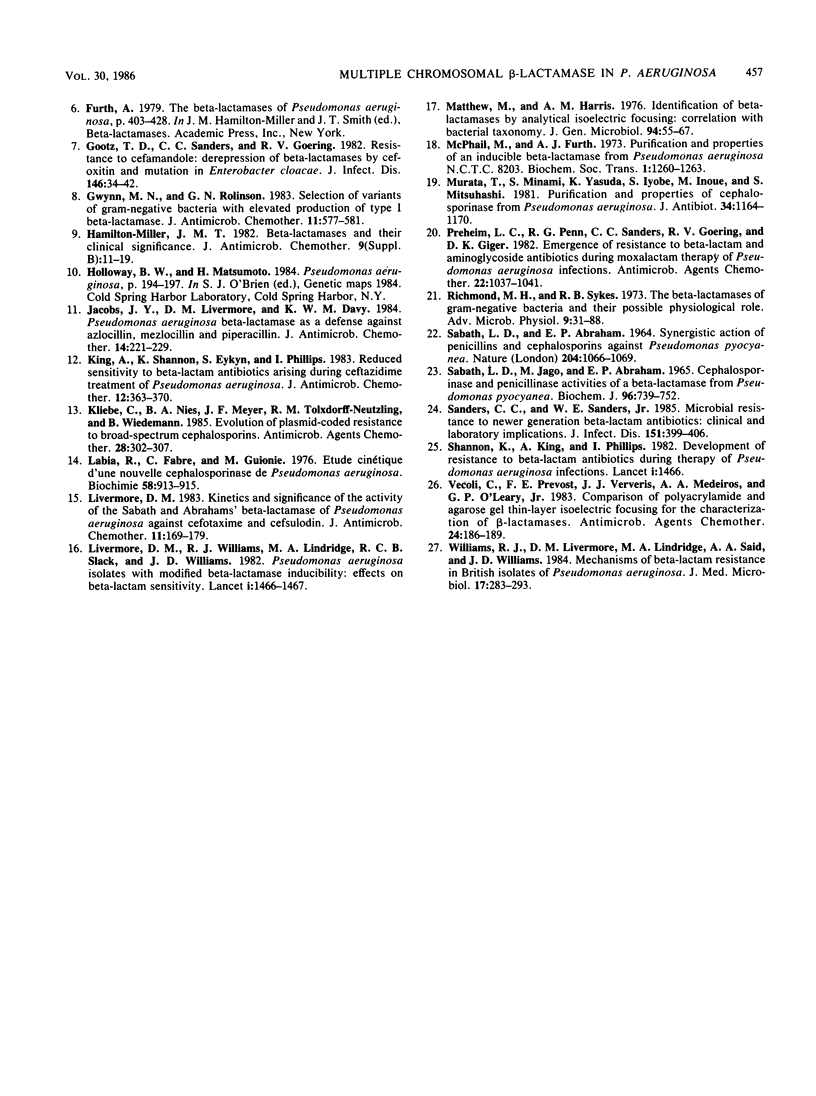

The multiple stages of derepression of the type I chromosomal beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa were examined. Mutants partially and fully derepressed for beta-lactamase were selected from a wild-type clinical isolate. An analysis of the beta-lactamase produced by these mutants and the induced wild type revealed significant differences in the products of derepression at each stage. Beta-lactamase produced by the fully derepressed mutant showed a lower affinity (Km, 0.113 mM) for cephalothin than that produced by the partially derepressed mutant (Km, 0.049 mM). However, due to a very large Vmax, the former possessed a much greater hydrolytic efficiency. Differences in substrate profile were also noted. Only beta-lactamase from the fully derepressed mutant hydrolyzed cefamandole, cefoperazone, and cefonicid. The partially derepressed mutant possessed a single beta-lactamase band with a pI of 8.4. The fully derepressed mutant possessed this band and an additional major band with a pI of 7.5. Induction of the wild type with cefoxitin produced both bands. The changes in physiologic parameters of the enzymes produced in the different stages of derepression suggest a complex system for beta-lactamase expression in P. aeruginosa. This may involve at least two distinct structural regions, each of which is under control of the same repressor.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Berks M., Redhead K., Abraham E. P. Isolation and properties of an inducible and a constitutive beta-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Gen Microbiol. 1982 Jan;128(1):155–159. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-1-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan L. E., Kwan S., Godfrey A. J. Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants with altered control of chromosomal beta-lactamase to piperacillin, ceftazidime, and cefsulodin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984 Mar;25(3):382–384. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis N. A., Orr D., Boulton M. G., Ross G. W. Penicillin-binding proteins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Comparison of two strains differing in their resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981 Feb;7(2):127–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/7.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flett F., Curtis N. A., Richmond M. H. Mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 18S that synthesizes type Id beta-lactamase constitutively. J Bacteriol. 1976 Sep;127(3):1585–1586. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1585-1586.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootz T. D., Sanders C. C., Goering R. V. Resistance to cefamandole: derepression of beta-lactamases by cefoxitin and mutation in Enterobacter cloacae. J Infect Dis. 1982 Jul;146(1):34–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwynn M. N., Rolinson G. N. Selection of variants of Gram-negative bacteria with elevated production of type 1 beta-lactamase. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983 Jun;11(6):577–581. doi: 10.1093/jac/11.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton-Miller J. M. beta-Lactamases and their clinical significance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1982 Feb;9 (Suppl B):11–19. doi: 10.1093/jac/9.suppl_b.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J. Y., Livermore D. M., Davy K. W. Pseudomonas aeruginosa beta-lactamase as a defence against azlocillin, mezlocillin and piperacillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984 Sep;14(3):221–229. doi: 10.1093/jac/14.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A., Shannon K., Eykyn S., Phillips I. Reduced sensitivity to beta-lactam antibiotics arising during ceftazidime treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983 Oct;12(4):363–370. doi: 10.1093/jac/12.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebe C., Nies B. A., Meyer J. F., Tolxdorff-Neutzling R. M., Wiedemann B. Evolution of plasmid-coded resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Aug;28(2):302–307. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labia R., Fabre C., Guionie M. Etude cinétique d'une nouvelle céphalosporinase de Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochimie. 1976;58(8):913–915. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(76)80279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore D. M. Kinetics and significance of the activity of the Sabath and Abrahams' beta-lactamase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa against cefotaxime and cefsulodin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983 Feb;11(2):169–179. doi: 10.1093/jac/11.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore D. M., Williams R. J., Lindridge M. A., Slack R. C., Williams J. D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates with modified beta-lactamase inducibility: effects on beta-lactam sensitivity. Lancet. 1982 Jun 26;1(8287):1466–1467. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew M., Harris A. M. Identification of beta-lactamases by analytical isoelectric focusing: correlation with bacterial taxonomy. J Gen Microbiol. 1976 May;94(1):55–67. doi: 10.1099/00221287-94-1-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T., Minami S., Yasuda K., Iyobe S., Inoue M., Mitsuhashi S. Purification and properties of cephalosporinase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1981 Sep;34(9):1164–1170. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preheim L. C., Penn R. G., Sanders C. C., Goering R. V., Giger D. K. Emergence of resistance to beta-lactam and aminoglycoside antibiotics during moxalactam therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982 Dec;22(6):1037–1041. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.6.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond M. H., Sykes R. B. The beta-lactamases of gram-negative bacteria and their possible physiological role. Adv Microb Physiol. 1973;9:31–88. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SABATH L. D., ABRAHAM E. P. SYNERGISTIC ACTION OF PENICILLINS AND CEPHALOSPORINS AGAINST PSEUDOMONAS PYOCYANEA. Nature. 1964 Dec 12;204:1066–1069. doi: 10.1038/2041066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabath L. D., Jago M., Abraham E. P. Cephalosporinase and penicillinase activities of a beta-lactamase from Pseudomonas pyocyanea. Biochem J. 1965 Sep;96(3):739–752. doi: 10.1042/bj0960739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C. C., Sanders W. E., Jr Microbial resistance to newer generation beta-lactam antibiotics: clinical and laboratory implications. J Infect Dis. 1985 Mar;151(3):399–406. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K., King A., Phillips I. Development of resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics during therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Lancet. 1982 Jun 26;1(8287):1466–1466. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecoli C., Prevost F. E., Ververis J. J., Medeiros A. A., O'Leary G. P., Jr Comparison of polyacrylamide and agarose gel thin-layer isoelectric focusing for the characterization of beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983 Aug;24(2):186–189. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. J., Livermore D. M., Lindridge M. A., Said A. A., Williams J. D. Mechanisms of beta-lactam resistance in British isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol. 1984 Jun;17(3):283–293. doi: 10.1099/00222615-17-3-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]