Abstract

Antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis in man may be exacerbated by infection and this effect may be mediated by bacterial endotoxin. There is evidence supporting a role for endotoxin in heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis in rats, but the role of endotoxin in this model in mice has not previously been explored. Previous data in mice on the role of complement in this model are conflicting and this may be due to the mixed genetic background of mice used in these studies. We used the model of heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis in mice and explored the role of endotoxin, complement and genetic background. In this study we show a synergy between antibody and endotoxin in causing a neutrophil influx. We also show that C1q-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to glomerular inflammation but this is seen only on a mixed 129/Sv × C57BL/6 genetic background. On a C57BL/6 background we did not find any differences in disease susceptibility when wildtype, C1q, factor B or factor B/C2 deficient mice were compared. We also demonstrate that C57BL/6 mice are more susceptible to glomerular inflammation than 129/Sv mice. These results show that endotoxin is required in this model in mice, and that complement does not play a major role in glomerular inflammation in C57BL/6 mice. C1q may play a protective role in mixed-strain 129/Sv × C57BL/6 mice, but the data may also be explained by systematic bias in background genes, as there is a large difference in disease susceptibility between C57BL/6 and 129/Sv mice.

Keywords: glomerulonephritis, complement, endotoxin, genetic, immune-complex, antibody, mouse

INTRODUCTION

Glomerulonephritis in man may be exacerbated by a systemic infection. The best example in humans is IgA nephropathy [1–3], although the effect is also well recognized in anti-GBM disease [4]. This suggests that, as well as immunological effector mechanisms, a second nonspecific pro-inflammatory signal may be necessary in some cases to initiate glomerular inflammation. Heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis is a model of antibody-mediated inflammation caused by a foreign antibody binding to the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). This model has been used in a variety of animals to explore the mechanisms leading to glomerular inflammation. Experiments in the rat showed a neutrophil influx that peaked after a few hours and resolved at 24 h, and revealed that proteinuria was dependent on the neutrophil influx [5,6]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that endotoxin, IL-1 or TNFα given one hour before injection of nephrotoxic antibody could exacerbate injury, as shown by an increased neutrophil influx and 24 h albuminuria [7]. The effect of endotoxin-contamination of nephrotoxic antibody batches was reported, and a correlation between the degree of endotoxin contamination of different batches of nephrotoxic rabbit antibody and the ability of these batches to induce albuminuria in the rat was found [8].

Heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis has also been established in the mouse [9]. In early studies in mice, morphological changes were not observed in the heterologous phase despite the administration of doses of antibody much larger than those required to cause heterologous injury in the rat [10]. We hypothesized that one reason that it proved more difficult to establish a reproducible heterologous model in the mouse was that there is a more significant requirement for endotoxin in this species. The studies in rat, referred to above [7,8], supported the hypothesis that endotoxin contamination of nephrotoxic antibody exacerbated disease in this model. However, the severity of disease caused by antibody with low levels of endotoxin was not directly compared with disease induced by the same antibody with endotoxin added.

The role of complement in the model of heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis in the mouse is unresolved. In the rat, complement-dependence has been shown [6, 11, 12]. This was deduced from experiments in which animals were depleted of complement by injections of aggregated human gamma globulin, or the complement-fixing ability of the nephrotoxic antibody was decreased by reduction with mercaptoethanol. Initial studies in the B10.D2 and C57BL/10 mice using cobra venom factor did not support a role for complement in this species [13,14]. A number of investigators have studied the role of complement in heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis in mixed-strain knockout mice. For example, two groups found that both the neutrophil influx and proteinuria in this model were dependent on the classical pathway [15,16]. However, in a third study it was reported that the neutrophil influx in C3 and C4 deficient mice was the same as in wild-type mice [17]. Many initial studies of ‘knockout’ mice, such as those described above, are performed in animals of mixed 129/Sv × C57BL/6 genetic background because these are usually the first animals available for study after the generation of a mouse with a specific targetted deletion.

We began by exploring systematically the requirement for endotoxin in a model of antibody-mediated acute nephrotoxic nephritis in the mouse. Our studies on the role of complement started with a comparison of wild-type and C1q-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 × 129/Sv mixed genetic background. We then compared wild-type mice with C1q, factor B and factor B/C2 deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background. In addition we compared wild-type mice of 129/Sv and C57BL/6 backgrounds to see if these strains differed significantly in the model of nephrotoxic nephritis. If this was the case, it would potentially complicate the interpretation of data in experiments in which mixed-strain 129/Sv × C57BL/6 mice are used.

METHODS

Mice

Age- and sex-matched mice, aged 6–12 weeks, were used in all experiments. C1q-deficient and factor B/C2-deficient mice were generated as described previously [18,19]. Factor B deficient mice were obtained from Dr H. Colten [20]. Complement deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background were obtained by backcrossing onto a C57BL/6 background for a minimum of 6 generations. Mice were kept in a standard animal house environment and experiments were performed according to institutional guidelines.

Preparation of nephrotoxic globulin

Nephrotoxic globulin was prepared as previously described [21]. The concentration of endotoxin was measured using a chromogenic Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate assay (Chromogenix, Molndal, Sweden) and the kinetic method according to the manufacurer's instructions.

Induction of glomerulonephritis

Glomerulonephritis was induced by a single injection of 4 mg nephrotoxic globulin via the tail vein. E.coli OH111 lipopolysacharide (Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, UK) was added to the globulin preparation as described under results. Mice were anaesthetized with intraperitoneal fentanyl and midazolam and exanguinated at 2 or 24 h after the induction of disease.

Histological studies and quantitative immunofluorescence

Kidneys were fixed for 4 h in Bouin's solution, transferred to 70% ethanol, and embedded in paraffin, or snap-frozen in isopentane and stored at −70°C. Sections embedded in paraffin were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reagent. Frozen sections were cut at a thickness of 5 µm. All light microscopic analysis and quantitative immunofluorescence was performed by an observer without knowledge of the sample identity. Neutrophils and apoptotic bodies were identified by their characteristic morphology on PAS-stained sections and counted at a magnification of ×1000 under oil immersion. In the kidney, 50 glomeruli per section were counted. To detect bound nephrotoxic antibody, direct immunofluorescence studies using FITC-conjugated monoclonal mouse antirabbit IgG (Sigma Chemical Co.) were performed. Staining of complement components was performed by indirect immunofluorescence as described previously [21]. Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence was performed as described previously [21].

TUNEL staining

Transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labelling (TUNEL) was performed using the FITC-Apoptag kit from Oncor (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) on Bouin's fixed paraffin embedded sections according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Albuminuria

Mice were placed in metabolic cages for 24 h collection of urine and albuminuria was calculated from the volume and albumin concentration. The latter was measured by radial immunodiffusion as previously described [21].

Statistics

Results of albuminuria and apoptotic bodies data are expressed as median (range) and analysed using a Mann–Whitney U-test. All other results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Groups of mice were compared using the student's t-test for comparisons of two groups of mice, and a one-way anova with Dunnett's post-test for more than 2 groups. Graphpad Prism (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to analyse the data. Differences were considered significant when P < 0·05.

RESULTS

Both endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody were required for glomerular inflammation

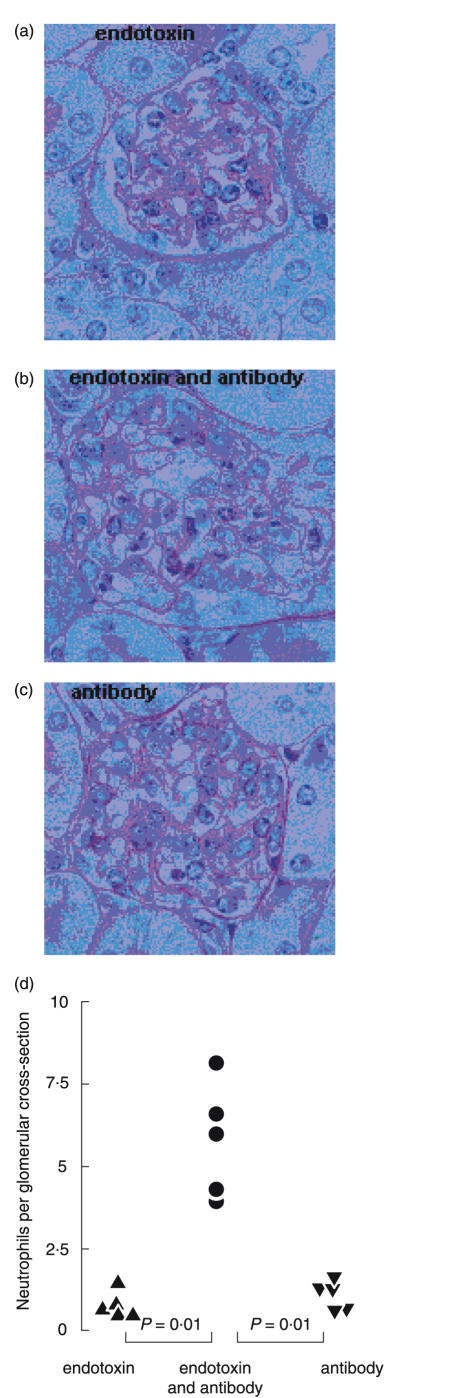

In preliminary experiments we found that batches of nephrotoxic globulin that had high incidental levels of endotoxin contamination caused a prominent glomerular neutrophil influx, whereas those with low levels did not. We therefore examined the effect on inflammation of adding endotoxin to nephrotoxic antibody containing low levels of endotoxin, and giving it as a single intravenous injection to C57BL/6 mice (n= 5 per group). The volume of nephrotoxic antibody used for each injection contained a total of 0·05 ng of endotoxin. We added 40 ng of endotoxin to each injection, with this amount being based on preliminary dose-ranging experiments. Two hours after injection, results for C57BL/6 mice (in neutrophils per glomerular cross-section) were, endotoxin alone: 0·884 ± 0·174; nephrotoxic antibody with endotoxin: 5·772 ± 0·767; nephrotoxic antibody alone (containing 0·05 ng endotoxin): 1·036 ± 0·189 (P < 0·01 for nephrotoxic antibody with endotoxin compared to either nephrotoxic antibody or endotoxin alone). Neutrophil numbers in the glomeruli of untreated C57BL/6 mice were 0·07 ± 0·0133. Figure 1 shows quantitative data and representative glomeruli 2 h after these three injections. These results showed that a mild neutrophil influx was seen with endotoxin or nephrotoxic antibody alone. However, more neutrophils were seen with both endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody, and there was synergy in the action of these two factors. Similar results were obtained in wild-type mice of mixed C57BL/6 × 129/Sv genetic background (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Antibody-mediated glomerular inflammation is endotoxin-dependent. Glomerular neutrophil influx in C57BL/6 mice 2 h after (a) 40 ng endotoxin, (b) 40 ng endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody or (c) nephrotoxic antibody alone. Representative histological sections and (d) quantification of neutrophil numbers are shown.

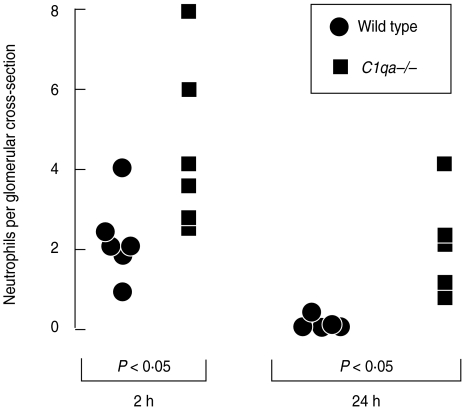

C1q-deficient mice are more susceptible to glomerular inflammation than wild-type mice on a mixed (C57BL/6 × 129/Sv) genetic background

We compared wild-type and C1q-deficient mice in heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis in order to assess the role of the classical pathway of complement in this model. Initial experiments were performed in mixed strain C57BL/6 × 129/Sv animals. C1q-deficient mice had more glomerular neutrophils at both 2 and 24 h after induction of disease, as shown in Fig. 2. Results at 2 h for wild-type and C1q-deficient mice (neutrophils per glomerular cross-section) were 2·25 ± 0·42 and 4·5 ± 0·85, respectively. At 24 h results were 0·16 ± 0·07 and 2·1 ± 0·58, respectively. (P < 0·05 at 2 h and P <0·01 at 24 h). Despite the difference in neutrophil influx, we did not demonstrate any diffence in albuminuria between wild-type and C1q-deficient mice. Results for wild-type and C1q-deficient mice, in µg/24 h as median (range) were: 523 (15–1135) and 709 (56–928).

Fig. 2.

C1q-deficient mice of mixed C57BL/6 × 129/Sv genetic background are more susceptible than wild-type mice to endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody-mediated glomerular inflammation

A possible explanation for the increased inflammation in C1q-deficient animals was an increased amount of rabbit IgG bound to the glomerulus. This was assessed by quantitiative immunofluorescence and no difference was found at 2 or 24 h after induction of disease. Results for wild-type and C1q-deficient mice at 2 h (in arbitrary fluorescence units) were 57·1 ± 2·5 and 37 ± 3·2, respectively. At 24 h results were 41 ± 3·9 and 40·2 ± 4·2, respectively. We have previously shown that mixed strain C1q-deficient mice of C57BL/6 × 129/Sv genetic background develop a spontaneous glomerulonephritis characterized by the presence of multiple apoptotic bodies [19]. We therefore thought that a failure to clear apoptotic bodies may explain the increased inflammation seen in C1q-deficient mice. Apoptotic bodies were identified morphologically and counted at 2, 10 and 24 h after induction of disease. There was no difference at any timepoint. Results for wild-type and C1q-deficient mice (apoptotic bodies per glomerular cross-section) at 2 h were 1 (0–6) and 2 (0–3), respectively. At 10 h results were 2 (1–6) and 1·5 (1–5). At 24 h results were 0 (0–2) and 0 (0–1). We also assessed numbers of apoptotic bodies at 10 h using TUNEL staining, and again there was no difference. Results for wild-type and C1q-deficient mice were 4 (1–6) and 3 (2–7).

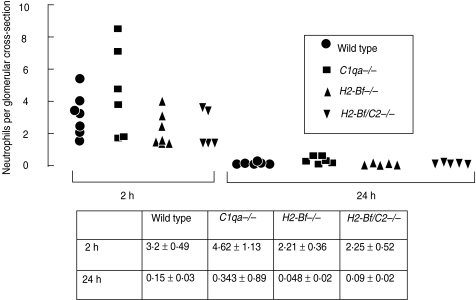

On a C57BL/6 background there were no differences in glomerular inflammation between wild-type, C1q-deficient, factor B-deficient, or factor B/C2-deficient mice

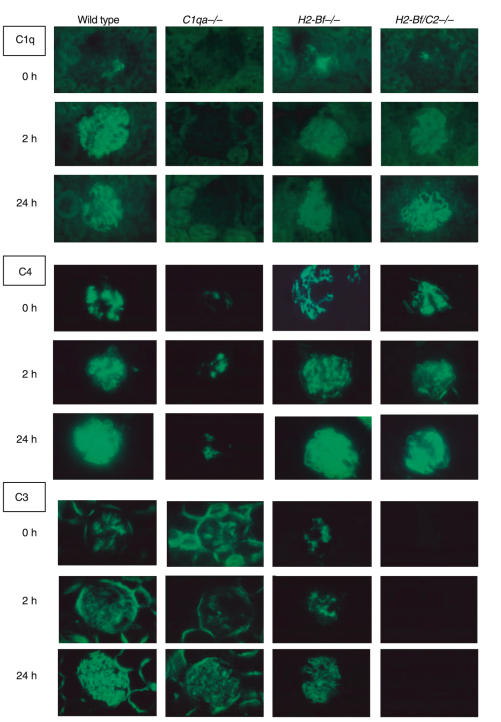

Despite the increased glomerular inflammation seen in C1q-deficient mice on a mixed genetic background, we did not detect any difference between wild-type and C1q-deficient mice on a pure C57BL/6 background, as shown in Fig. 3. We also compared disease in factor B deficient mice, and in mice doubly deficient in factor B and C2, on a C57BL/6 genetic background, with wildtypes. At 2 and 24 h there were no differences in glomerular neutrophil numbers between any of these groups. Results are shown numerically and graphically in Fig. 3. These data showed that neither the classical nor the alternative pathway of complement played a major role in the neutrophil in pathogenesis in this model in C57BL/6 mice. Despite this, we demonstrated that the classical pathway of complement was activated, with capillary wall C1q, C4 and C3 staining at 2 h in all mice with an intact classical pathway. At 24 h there was capillary wall C3 staining in C1q-deficient mice, demonstrating alternative pathway activation. Representative glomeruli are shown in Fig. 4. This showed that the classical and alternative pathway of complement were activated, despite our finding that these pathways were not necessary for pathogenesis. This suggests that these complement components are present without any relevant biological activity.

Fig. 3.

On a pure C57BL/6 genetic background there were no differences in glomerular inflammation when wild-type, C1q-deficient, factor B deficient, or factor B/C2-deficient mice were compared.

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescence staining for C1q, C4 and C3 at baseline and 2 and 24 h after induction of disease in wild-type and complement deficient mice. In untreated mice (0 h) there were sparse C1q deposits in all mice except C1qa–/– animals, prominent mesangial C3 deposits in all mice except H2-Bf/C2–/– animals, and mesangial C4 deposits in all mice, with less C4 present in C1qa–/– mice than other groups. At 2 h and 24 h there was evidence of classical pathway activation, with both C1q and C4 deposited on the capillary wall in the glomeruli of all animals except C1qa−/− mice. At 24 h, as well as evidence of classical pathway activation, there was evidence of alternative pathway activation, with linear capillary wall C3 in the glomeruli of C1qa–/– mice. Tubular C3 was seen in all mice except H2-Bf–/– and H2-Bf/C2–/–.

We measured albuminuria in several experiments. In two experiments we assessed albuminuria in animals of the genotypes shown in Fig. 3 (both n= 5–7 per group). In one experiment the results in µg/24 h as median (range), for wildtype, C1qa−/−, H2-Bf−/− and H2-Bf/C2−/− mice, respectively, were: 285 (41–622), 6115 (2109–6903), 2029 (276–2790) and 856 (58–8890). In another experiment the results, in the same order, were: 143 (103–2357), 168 (39–1033), 52 (34–102) and 97 (7–348). In the first experiment wild-type mice had significantly less proteinuria than C1qa−/− mice, and in the second experiment wild-type mice had significantly more albuminuria than H2-Bf−/− mice. There was clearly more albuminuria overall in the first experiment. In summary, we did not demonstrate any consistent differences in albuminuria. However, we found a large variation between mice in the same group, and between different experiments. This variability has been described by other workers using this model [22], and may be a property of the nephrotoxic antibody preparation. Consequently we do not feel that we have confidently excluded the fact that differences in susceptibility to albuminuria may exist.

C57BL/6 mice were more susceptible than 129/Sv mice to glomerular inflammation

The differences that we had seen between C1q-deficient and wild-type mice on a mixed C57BL/6 × 129/sv genetic background were not seen in pure C57BL/6 mice. Therefore it seemed possible that the differences between groups of mixed strain animals could have reflected differences in background genes rather than the presence or absence of C1q. To explore this possibility, we compared 129/Sv and C57BL/6 mice to see if they differed in their response to endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody.

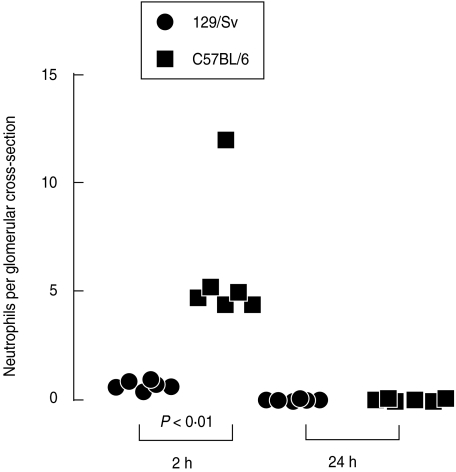

We examined kidney histology in 129/Sv and C57BL/6 mice after the injection of endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody (n = 5–6 per group). Data from this experiment are shown in Fig. 5. At 2 h after injection of 4 mg of nephrotoxic antibody, containing more than 40 ng endotoxin, C57BL/6 mice had significantly more neutrophils in their glomeruli than 129/Sv mice but there was no difference at 24 h. Results for 129/Sv and C57BL/6 mice (in neutrophils per glomerular cross-section) at 2 h were 0·73 ± 0·87 and 6·0 ± 0·21, respectively (P < 0·01). At 24 h results were 0·09 ± 0·02 and 0·093 ± 0·023, respectively. There were more neutrophils in the glomeruli of untreated C57BL/6 than 129/Sv mice (n = 10–12 per group). Neutrophils numbers per glomerular cross section were 0·07 ± 0·013 and 0·028 ± 0·01, respectively (P < 0·05). However these numbers were much lower than those present after induction of disease. These data showed that 129/Sv mice were resistant to endotoxin and antibody-mediated glomerular inflammation whereas C57BL/6 mice were susceptible. We did not find significant albuminuria in either C57BL/6 or 129/Sv mice in these experiments. As discussed above, we found much variability in albuminuria in this model in our hands, and a significant neutrophil influx did not always result in albuminuria. The increased glomerular neutrophil influx in C57BL/6 mice may have been due to increased binding of nephrototoxic antibody. To examine this possibility we measured the amount of nephrotoxic antibody in the glomeruli of C57BL/6 and 129/Sv mice at 2 h after induction of disease using quantitative immunofluorescence for rabbit IgG (n= 6 per group). No significant difference was found. Results for C57BL/6 and 129/Sv mice were 26·83 ± 1·64 and 34·3 ± 3·02, respectively.

Fig. 5.

C57BL/6 mice were more susceptible than 129/Sv mice to endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody mediated glomerular inflammation.

DISCUSSION

In this study we made a number of novel observations about heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis in mice. Firstly, we saw a marked synergistic effect between endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody. Secondly, we found an increased susceptibility to disease in C1q-deficient mice on a mixed C57BL/6 × 129/Sv genetic background but not on a pure C57BL/6 background. We also found no difference between wildtype, factor B and factor B/C2 deficient mice on a C57BL/6 genetic background. Finally, there was a large difference in susceptibility to glomerular inflammation between 129/Sv and C57BL/6 mice.

Observations in man suggest that a nonspecific inflammatory stimuli may exacerbate immune-mediated glomerular inflammation. Immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis, such as IgA nephropathy, frequently presents following an infection, often of the respiratory tract, suggesting that both an immune and a nonspecific signal are necessary to initiate inflammation [1–3]. Intercurrent infection can exacerbate both renal and pulmonary injury in anti-GBM disease [4]. Further evidence suggesting the need for a second nonspecific inflammatory stimulus is the observation that antibody may bind to the glomerular basement-membrane of both native and transplanted kidneys in the absence of significant clinical disease [23,24].

In keeping with these observations in man, bacterial endotoxin has been shown to exacerbate disease in heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis in the rat [7]. In that study, increased disease was also seen after TNFα and IL-1. Subsequent work showed that blocking these factors with antibody or soluble receptors also inhibited the effect of endotoxin [25,26]. In these reports, endotoxin was given one hour before nephrotoxic antibody, allowing a period of time for the release and subsequent actions of inflammatory mediators to occur. Interestingly, blockade of TNFα was also effective in a model of crescentic nephritis in the WKY rat (not related to endotoxin contamination of nephrotoxic serum), suggesting that TNF is a mediator of antibody-dependent glomerular inflammation [27]. Despite these extensive studies in the rat, the role of endotoxin in murine heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis has not previously been explored, and the level of endotoxin contamination of nephrotoxic antibody preparations has not generally been reported. In the present study, we have shown a synergistic effect of endotoxin and antibody when they are given at the same time, suggesting an immediate effect of endotoxin in murine heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis. The requirement for both endotoxin and nephrotoxic antibody has implications for the interpretation of results of experiments in this model. Variation in either antibody- or endotoxin-dependent pathways may be responsible for differences that are observed between groups of animals.

In the present study we found an increased susceptibility to disease in C1q-deficient mice on a mixed C57BL/6 × 129/Sv genetic background. We explored a number of possible reasons for the increased glomerular inflammation that was seen in mixed strain C1q-deficient mice. The increased inflammation could have been the result of increased binding of nephrotoxic antibody, but we did not detect any difference. The spontaneous glomerulonephritis that develops in C57BL/6 × 129/Sv C1q-deficient mice is characterized by the presence of multiple apoptotic bodies [19]. Therefore it was possible that the increased inflammation seen in mixed strain C1q-deficient mice in heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis reflected a failure to clear apoptotic bodies. However we found also no difference in the numbers of apoptotic bodies in C1q-deficient or wild-type mice.

The present study is the first to address the role of complement in pure strain knockout mice. The data show that on a pure C57BL/6 genetic background, there was no difference in glomerular neutrophil influx between wildtype, C1q-deficient mice, factor B-deficient mice or animals doubly deficient in C2 and factor B. These results show that neither the classical nor the alternative pathway of complement play a major role in the neutrophil influx in C57BL/6 mice in this particular model of glomerulonephritis induced by a single dose of nephrotoxic antibody. This is in agreement with the results of Tang [17], but not those of Herbert or Sheerin [15,16]. These three studies used mixed-strain mice, and systematic variation in genetic background between groups of 129/Sv × C57BL/6 mice may account for the variation in findings.

Although we did not find a difference between wild-type and C1q-deficient C57BL/6 mice in this model, we did find increased disease in mixed-strain (C57BL/6 × 129/Sv) C1q-deficient animals compared to wildtypes. Again, systematic variation in genetic background between groups of 129/Sv × C57BL/6 mice, rather than the presence or absence of C1q, may account for these results. However, increased glomerular neutrophils were seen at both 2 and 24 h in C1q-deficient 129/Sv × C57BL/6 mice, whereas the difference in susceptibility to inflammation between C57BL/6 and 129/Sv mice was apparent only at 2 h. Therefore it remains possible that the increased inflammation in C1q-deficient 129/Sv × C57BL/6 mice is due to a lack of C1q.

The large differences that we found in susceptibility to inflammation between 129/Sv and C57BL/6 mice suggest that variations in the mixture of background genes in the mixed-strain animals might lead to phenotypic differences between groups of mice following the administration of an exogenous phlogistic agent. This complicates the interpretation of experiments performed in ‘knockout’ mice as it is evident that observed differences between groups of mice may not be due exclusively to the presence or absence of the gene of interest. The increased susceptibility to glomerular inflammation in C57BL/6 compared to 129/Sv mice has implications for experimental systems other than heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis. Many models of spontaneous immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis have been reported in mice of mixed C57BL/6 × 129/Sv genetic background [19,28,29]. If 129/Sv and C57BL/6 mice have widely different susceptibilities to antibody-mediated glomerular inflammation, variation in the background genes between groups of wild-type and knockout mice may result in a difference in the numbers of mice developing glomerulonephritis. The increased susceptibility to disease in C57BL/6 mice may also apply to models of inflammation other than immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis. A recent study of thioglycollate-mediated peritonitis has also shown more severe disease in C57BL/6 mice than 129/Sv mice, and highlighted the pitfalls of using mixed strain animals [30].

In summary, we have shown that neither the classical nor the alternative complement pathway plays a major role in heterologous nephrotoxic nephritis in C57BL/6 mice. C1q has a protective role in mixed strain C57BL/6 × 129/Sv mice in this model, but an alternative explanation for the data is systematic bias in the background genes of groups of mixed-strain experimental animals. We have also highlighted the role of endotoxin in this model. Both the genetic background and the effects of endotoxin contamination have important implications for the design and interpretation of studies using antibody-mediated murine models of glomerulonephritis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Margarita Lewis for processing histological samples, to Dr H Colten and Dr M Botto for providing complement deficient mice. This programme of work is supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 054838) and an MRC clinical training fellowship to MR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodicio JL. Idiopathic IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1984;25:717–29. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamoto Y, Asana Y, Dohi K, et al. Primary IgA glomerulonephritis and Schonlein-Henoch Purpura nephritis: clinicopathological and immunohistological characteristics. Q J Med. 1978;188:495–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frimat L, Briançon S, Hestin D, et al. IgA nephropathy. prognostic classification of end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2569–75. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.12.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rees AJ, Lockwood CM, Peters DK. Enhanced allergic tissue injury in Goodpasture's syndrome by intercurrent bacterial infection. Br Med J. 1977;2:723–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6089.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unanue ER, Dixon FJ. Experimental glomerulonephritis. V. Studies on the interaction of nephrotoxic antibodies with tissues of the rat. J Exp Med. 1965;121:697. doi: 10.1084/jem.121.5.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochrane CG, Unanue ER, Dixon FJ. A Role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and complement in nephrotoxic nephritis. J Exp Med. 1965;122:99–119. doi: 10.1084/jem.122.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomosugi NI, Cashman SJ, Hay H, et al. Modulation of antibody-mediated glomerular injury in vivo by bacterial lipopolysaccharide, tumour necrosis factor, and Il-1. J Immunol. 1989;142:3083–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karkar AM, Rees AJ. Influence of endotoxin contamination on anti-GBM antibody induced glomerular injury in rats. Kidney Int. 1997;52:1579–83. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assmann KJ, Tangelder MM, Lange WP, et al. Anti-GBM nephritis in the mouse: severe proteinuria in the heterologous phase. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1985;406:285–99. doi: 10.1007/BF00704298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unanue ER, Dixon FJ. Experimental glomerulonephritis. immunological events and pathogenetic mechanisms. Adv Immunol. 1967;6:1–90. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammer DK, Dixon FJ. Experimental glomerulonephritis. III. Immunologic events in the pathogenesis of nephrotoxic seum nephritis in the rat. J Exp Med. 1963;117:1019–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.117.6.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unanue ER, Dixon FJ. Experimental glomerulonephritis. IV. Participation of complement in nephrotoxic serum nephritis. J Exp Med. 1964;119:965. doi: 10.1084/jem.119.6.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tipping PG, Huang XR, Berndt MC, et al. A role for P selectin in complement-independent neutrophil-mediated glomerular injury. Kidney Int. 1994;46:79–88. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrijver G, Assmann KJ, Bogman MJ, et al. Antiglomerular basement membrane nephritis in the mouse. Study on the role of complement in the heterologous phase. Laboratory Invest. 1988;59:484–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbert M, Takano T, AP, et al. Acute nephrotoxic serum nephritis in complement knockout mice. relative roles of the classical and alternate pathways in neutrophil recruitment and proteinuria. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:2799–803. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.11.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheerin NS, Springall T, Carroll MC, et al. Protection against anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM)-mediated nephritis in C3- and C4-deficient mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;110:403–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4261438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang T, Rosenkranz A, Assmann KJM, et al. A role for Mac-1 (CDIIb/CD18) in immune complex-stimulated neutrophil function in vivo. Mac-1 deficiency abrogates sustained Fcgamma receptor-dependent neutrophil adhesion and complement-dependent proteinuria in acute glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1853–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor PR, Nash JT, Theodoridis E, et al. A targeted disruption of the murine complement factor B gene resulting in loss of expression of three genes in close proximity, factor B, C2, and D17H6S45. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1699–704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botto M, Dell’Agnola C, Bygrave AE, et al. Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat Genet. 1998;19:56–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto M, Fukuda W, Circolo A, et al. Abrogation of the alternative complement pathway by targeted deletion of murine factor B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8720–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robson MG, Cook HT, Botto M, et al. Accelerated nephrotoxic nephritis is exacerbated in C1q-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:620–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coxon A, Cullere X, Knight S, et al. Fc gamma RIII mediates neutrophil recruitment to immune complexes. a mechanism for neutrophil accumulation in immune-mediated inflammation. Immunity. 2001;14:693–704. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ang C, Savige J, Dawborn J, et al. Anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM)-antibody-mediated disease with normal renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:935–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.4.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalluri R, Torre A, Shield CF, III, et al. Identification of alpha3, alpha4, and alpha5 chains of type IV collagen as alloantigens for Alport posttransplant anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies. Transplantation. 2000;69:679–83. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002270-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karkar AM, Koshino Y, Cashman SJ, et al. Passive immunization against tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and IL-1 beta protects from LPS enhancing glomerular injury in nephrotoxic nephritis in rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:312–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb07948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karkar AM, Tam FW, Steinkasserer A, et al. Modulation of antibody-mediated glomerular injury in vivo by IL-1ra, soluble IL-1 receptor, and soluble TNF receptor. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1738–46. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karkar AM, Smith J, Pusey CD. Prevention and treatment of experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis by blocking tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:518–24. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.3.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hibbs ML, Tarlinton DM, Armes J, et al. Multiple defects in the immune system of Lyn-deficient mice, culminating in autoimmune disease. Cell. 1995;83:301–11. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Z, Koralov SB, Kelsoe G. Complement C4 inhibits systemic autoimmunity through a mechanism independent of complement receptors CR1 and CR2. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1339–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White P, Liebhaber SA, Cooke NE. 129X1/SvJ mouse strain has a novel defect in inflammatory cell recruitment. J Immunol. 2002;168:869–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]