Abstract

The yeast inheritable [URE3] element corresponds to a prion form of the nitrogen catabolism regulator Ure2p. We have isolated several orthologous URE2 genes in different yeast species: Saccharomyces paradoxus, S. uvarum, Kluyveromyces lactis, Candida albicans, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. We show here by in silico analysis that the GST-like functional domain and the prion domain of the Ure2 proteins have diverged separately, the functional domain being more conserved through the evolution. The more extreme situation is found in the two S. pombe genes, in which the prion domain is absent. The functional analysis demonstrates that all the homologous genes except for the two S. pombe genes are able to complement the URE2 gene deletion in a S. cerevisiae strain. We show that in the two most closely related yeast species to S. cerevisiae, i.e., S. paradoxus and S. uvarum, the prion domains of the proteins have retained the capability to induce [URE3] in a S. cerevisiae strain. However, only the S. uvarum full-length Ure2p is able to behave as a prion. We also show that the prion inactivation mechanisms can be cross-transmitted between the S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum prions.

INTRODUCTION

The last decade has seen the emergence of a new paradigm in yeast herited from the study of a mammalian disease: the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. A new class of agent transmits this disease: the prions. Such pathogenic agent has been proposed to be the consequence of a structural change in a particular protein: the PrP. The prion concept is based on the assumption that the so-called prion protein undergoes (under certain and not yet well-understood conditions) a profound conformational change during its conversion into its abnormal form. In its abnormal form the cellular protein is able to cause autocatalytic conversion of the normal protein into its abnormal shape.

Using genetic arguments, Reed Wickner presented in 1994 the [URE3] phenotype as the consequence of an altered form of Ure2p (Wickner, 1994). In this prion model, the cellular protein Ure2p can be converted into the [URE3] state (Ure2p[URE3]). This modification would abolish the normal function of Ure2p, leading to a phenotype identical to the one observed in ure2 mutant strain. The behavior of [URE3] is consistent with the prion paradigm and provides a powerful model for the replication of such molecules.

Since this time, the yeast prion world has become more and more populated. As initially suggested by Reed Wickner, another nonmendelian element [PSI+], corresponding to the inactivation of Sup35p, was demonstrated to be the consequence of a prion mechanism. Emerging from the study of [PSI+], a new phenotype related to the de novo induction of [PSI+] and named [PIN+] was also classified as a prion (Derkatch et al., 1997, 2000).

The two more studied yeast prion proteins Ure2p and Sup35p have revealed a common structural organization in which the prion properties are enciphered in a prion domain. In both cases, this domain is characterized by an abnormally rich composition in Q+N. Michelitsch and colleagues have taken advantage of this bias to screen several genomic libraries and found that this property was shared among 107 polypeptides encoded by the yeast genome (Michelitsch and Weissman, 2000). One of these putative prion domain encoded by YPL226w (called NEW1) has further been demonstrated to be a real one in vivo (Santoso etal., 2000). Other in silico approaches have also designed the protein encoded by RNQ1 as a prion (Sondheimer and Lindquist, 2000).

In an attempt to identify the gene encoding the prion-like [PIN+], a genetic screen led to the isolation of 11 candidate genes, among which are the genes encoding the URE2, RNQ1 prion protein and the NEW1 gene encoding a presumptive prion protein (Derkatch et al., 2001; Osherovich and Weissman, 2001). Altogether, these experiments argue for the existence of a prion network in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The status of this network is not known in other yeast species. The study of orthologous SUP35 genes has demonstrated that the prion property of this protein is partially conserved among the evolution (Chernoff et al., 1995; Kushnirov et al., 2000; Santoso et al., 2000; Nakayashiki et al., 2001; Resende et al., 2002).

In this study, we have isolated different orthologous URE2 genes from several yeast species. In most of them, a Q/N-rich domain is found. The evolution rate of this domain appears to be much higher that the one of the functional domain. The functionality in the Nitrogen Catabolic Repression (NCR) as well as the prion properties of these new genes has been studied in S. cerevisiae. We demonstrated that although able to complement a URE2 deletion, some of these genes could not initiate the de novo [URE3] appearance. We have systematically investigated the prion properties of the Q/N-rich region of these genes. Finally, we have analyzed the “species barrier,” i.e., the ability of one orthologous URE2 gene to propagate the prion form obtained with the S. cerevisiae URE2 gene. The results obtained clearly identified the yeast prion [URE3] as a nonconserved phenotype among the hemiascomycete phylum. This situation is profoundly different from the SUP35 story because no species barrier could be observed. One orthologous gene is intriguing in that the full-length URE2 gene is unable to induce [URE3], although its Q/N-rich domain alone induces [URE3] very efficiently.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Microbiological Methods

S. cerevisiae strain CC30 (MATα, trp1-1, ade2-1, leu2-3, 112, his3-11, 15, can1-100, Δura2::HIS3) was used as the wild-type parent. The strain AB34 is isogenic except that it carries the [URE3] element originally described by Aigle and Lacroute (1975) that was transmitted by cytoduction. Functional complementation tests were carried out using the AF36 strain (MATa, trp1-1, ade2-1, leu2-3, 112, his3-11, 15, can1-100, Δura2::HIS3, cyh2r, Δure2::CYH2).

Growth and handling of S. cerevisiae involved standard techniques. Strains were grown in complete liquid medium/plates YPGA (1% yeast extract, 1% bactopeptone, 2% glucose, 30 mg/l adenine) or YPGALA (1% yeast extract, 1% bactopeptone, 2% galactose, 30 mg/l adenine) or selective medium/plates WO (2% glucose, 0.7% yeast nitrogen base, plus nutriments) or WOGal (2% galactose, 0.7% yeast nitrogen base, plus nutriments). [URE3]/Usa+ colonies were selected on a minimal medium containing ammonia as nitrogen source and supplemented with appropriate amino acids except uracil, and 15 mg/l ureidosuccinate (USA) as previously described (Lacroute, 1971). Strains were cured of the [URE3] determinant by growth on YPGA/YPGALA medium supplemented with 5 mM GuHCl. Transformation was achieved by the lithium acetate method (Gietz et al., 1992).

Screening of URE2 Genes

Genomic DNA from Saccharomyces paraduxus has been amplified with primers ureD (5′-ATGATGAATAACAACGGCAACCAAGTGTCGAATCTCTCCAATGCGCTCCG) and ureR (5′-TCATTCACCACGCAATGCCTTGATGACCGCGGGTCTTCTCATCATATGC) using a Robocycler Gradient Temperature Cycler (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), at different hybridization temperatures ranging from 38 to 49°C during 1 min, followed by a 1.5-min elongation step. Different amplification products were cloned and sequenced. A 1-kb fragment product from S. paradoxus was identified as an homologous gene of URE2. Three genomic libraries of S. paradoxus, Kluyveromyces lactis, and Saccharomyces uvarum constructed in pYCBL1 vector (kindly given by E. Petrochilo, CGM, CNRS Gif) were screened using the 1-kb fragment amplified from S. paradoxus as a radioactive-labeled probe, according to standard procedures. Clones of each library (n = 60,000) were hybridized at 42°C in presence of 50 or 25% formamide for the S. paradoxus, S. uvarum, and K. lactis libraries, respectively. Positive clones were subsequently sequenced.

A 415-bp DNA sequence homologous to the URE2 gene was identified by BLAST search in the Candida albicans chromosomal sequence library, in GenBank (265126A03.x1.seq). A 310-bp fragment internal to this sequence was amplified by PCR on genomic DNA with primers 27 (5′-CTGCTGCTTATACTGCTGGTACTACTC) and 28 (5′-TACGTTGAGACAATAATATCAAAAGCC). The amplified product was used as a radioactive-labeled probe to hybridize a genomic library of C. albicans constructed in Ycp50 vector (Pr. Mick Tuite, University of Canterbury, Kent, United Kingdom). Clones (n = 108) were screened at 42°C in presence of 50% formamide, and one positive clone was selected and sequenced.

The sequence data of the two Schizosaccharomyces pombe genes were produced by the Schizosaccharomyces pombe Genome Sequencing Group at the Sanger Centre and can be obtained from ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/yeast/sequences/pombe.

Sequence Analysis of Various S. cerevisiae Prion Domain

The PCR amplification was realized using the Whole Cell Yeast PCR Kit (Bio101, Illkirch, France) with the following primers: 5′-AAACCATAGAACGCCGAAACA-3′ and 5′-CAAATTCGGGGGCCCTATGT-3′. The PCR product was typically 900-bp long, the yield varying depending of the strain used. The sequence was obtained with the primer 5′-CAAATTCGGGGGCCCTATGT-3′.

Plasmid Construction

The full-length or prion domain of the URE2 open reading frames (ORFs) of the various yeast species were cloned into the pYeHFn2L vector or its derivates (Cullin and Minvielle, 1994). The resulting plasmids express the Ure2p protein under the control of the inducible promoter GAL10-CYC1. Each URE2 ORF corresponding to different species were amplified by PCR with two oligonucleotides that introduce a restriction site at the 5′- and 3′-end of the gene. The resulting cassette was cloned into the same sites of plasmids pYeHFn2L (with the LEU2-selectable marker), pYeHFn2T (with the TRP1-selectable marker) or pYeHFn2A (with the ADE2-selectable marker) to yield pYe2L/URE2, pYe2T/URE2, or pYe2A/URE2, respectively. The Prion Domain of the URE2 ORFs were amplified and cloned using the same experimental procedures. The prion domains were amplified using the pYe2L(L/T)/URE2 plasmid as matrix, an oligonucleotide located in the GAL10 promoter (CCTTTGTAGCATAAATTAC), and a specific oligonucleotide that introduce a STOP codon and a restriction site at the 3′-end of the N-terminus domain. The resulting fragments were cloned between the BamHI and the specific sites of the pYeHFn2L or pYeHFn2T plasmids to generate pYe2L(L/T)/URE2ΔC.

The different oligonucleotides as well as the length of the proteins produced and the selectable marker used are summarized in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences

| Species | Length (aa) | Marker |

|---|---|---|

| K. lactis | ||

| 5′ataagaatgcggccgcTCACGCTTGCTGTTGTGAC3′ | 124 | Leu2, Trp1 |

| 5′cgggatccATGCAACAAGATATGC3′ | 389 | Leu2 |

| 5′cgccttaggCTACTCTCCGCGTAATG3′ | ||

| S. paradoxus | ||

| 5′ataagaatgcggccgcTCAATCCGAAAATGCCTG3′ | 98 | Leu2, Trp1 |

| 5′cgggatccATGATGAATAACAACG3′ | 358 | Leu2 |

| 5′cgcctaggTTATTCACCACGCAATG3′ | ||

| C. albicans | ||

| 5′ataagaatgcggccgcTCATTGTTGTTGTTGAG3′ | 64 | Leu2, Trp1 |

| 5′cgggatccATGATGTCTACTGATCAAC3′ | 320 | Leu2 |

| 5′cgccttaggTTAATCTCCACGTAAAGC3′ | ||

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| 5′cgcctaaggTCAATCCGAAAATGCCTG3′ | 93 | Leu2, Trp1 |

| 5′cgcggatccATGATGAATAACAACGGCAAC3′ | 354 | Leu2 |

| 5′gcgccttaggTCATTCACCACGCAATGCCTTGATG3′ | ||

| S. uvarum | ||

| 5′cgcctaaggTCAATCCGAGAACGCCTGC3′ | 84 | Leu2, Trp1 |

| 5′cgggatccATGATGAATAACwwcggTAACC3′ | 345 | Leu2 |

| 5′cgccttaggTCACTCGCCACGTAATGC3′ | ||

| S. pombe | ||

| 5′gcggatccATGGCTCAATTCACTTTATG3′ | 230 | Leu2 |

| 5′cgccttaggTTAATTATCCAAAGCCTTTG3′ | ||

| S. pombe | ||

| 5′gcggatccATGGCTCATTTTACTTTATAC3′ | 229 | Ade2 |

| 5′cggaattcTCAATGTTGTTCTTTGGCCTT3′ |

The PCR fragment was cloned in expression vectors based on different selectable markers that are indicated. The lengths (in amino acids) of the produced protein are indicated.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

Spb1: AF395117; spb2: AF213355; Sp: AF260775; Kl: AF260776; Ca: AF260777

RESULTS

In Silico Analysis of the Heterologous Ure2p

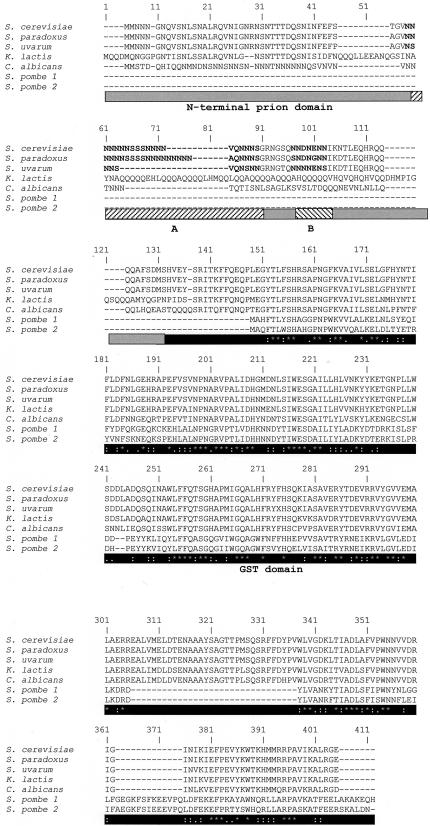

Domain Conservation The multiple alignment of the seven orthologous Ure2p studied in this work (isolated from S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, S. uvarum, K. lactis, C. albicans, and S. pombe) demonstrates that the protein is composed of two regions, in which the homology clearly differs. The main partition of the protein separates the prion domain (PrD) in N-terminal position and the GST-like functional domain on C-terminal side (Figure 1). This last region is delimited by the methionine at position 94 of S. cerevisiae Ure2p sequence. This part of the protein adopts the same folding than the GST proteins. However, a flexible domain that extends from the core of this domain is never found in GST proteins (Bousset et al., 2001; Umland et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

Multiple alignment of full-length URE2p in nearly related species of S. cerevisiae. The gray box corresponds to the N-terminal prion domain. Within this domain, two hatched boxes delimit the small subregions A and B described in the text. The dark box corresponds to the C-terminal GST-like domain.

A more detailed analysis of the PrD from the three more closely related species of Saccharomyces (S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, and S. uvarum) identifies several subdomains, which can be subdivided in three conserved parts, separated by variable segments noted A and B (Figure 1). These two small regions (A and B) seem to have preferentially accumulated mutations by a slippage process, leading to a repetition of one asparagine codon (AAT), whereas the functional GST-like domain and the three N-terminal subdomains evolved by a substitution process. Thus the different domains and subdomains of the Ure2 proteins have diverged by different evolutionary mechanisms.

Evolution Rate of the Ure2p-PrD and Ure2p-GST Domain Among the seven URE2-like ORFs characterized in this work, only five seem to be genuine orthologous sequences. The other two proteins encoded by the S. pombe genome have to be considered as paralogous genes of the URE2 group. Indeed, both genes lack the characteristic PrD, and no significant remains of an ancestral PrD can be found in the leader sequence of the nucleic coding sequences. Moreover, the specific clipped region (from Glu-273 to Phe-294) is never present in both proteins. The alignment of GST domains can be easily constructed for the five other orthologous sequences, but PrDs can be correctly aligned only for three species namely Sc, Sp, and Su (Figure 1). For K. lactis, only the N-terminal part of the prion region can be approximately aligned. The two subregions A and B previously described are substituted in this species by a poly-glutamine–rich domain. The PrD from the last species, C. albicans, presents no similarity with the others, except in the high level of glutamine and asparagine residues.

Overall, these differences seem to indicate that the PrD diverges faster than the GST one.

Conservation among other Yeast Species The Genolevure Project (Feldmann, 2000) had given access to the partial genome sequences of 13 hemiascomycetes. We used tblastn (Altschul et al., 1997) to search a database consisting of 49,203 sequence tags issued from this project. Two query sequences were used, the first corresponding to the Ure2p-GST domain, and the second corresponding to the PrD of Ure2p from S. cerevisiae (amino acids 1–93). The GST query allowed us to find significant hits in five new species. For four of these, it was possible to observe the presence or the absence of a region corresponding to the amino acids 270–290 in S. cerevisiae. This part of the protein corresponds to a loop specific to the Ure2p family and absent in other GST-like proteins. The presence or absence of this loop is given in Table 2. From the second query no significant hit was found. This absence of hit does not mean a PrD is absent in the 5′-terminal of the two new URE2 family members though, because large parts of the studied genomes were not present in this databank.

Table 2.

Search of the clip structure in the orthologous URE2 genes partially sequenced in the genolevure project

| Species | URE2 loop |

|---|---|

| Pichia angusta | + |

| Pichia farinosa | - |

| Saccharomyces exiguus | + |

| Yiarovia lipolitica | ? |

| Candida tropicalis | - |

Intraspecies Variation of the N-terminus Domain of the URE2 Gene

Further to the observation of the variability in the length of the asparagines repeats for closely related yeast species (S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, and S. uvarum), we wondered if such characteristic could be found inside the S. cerevisiae species. For that purpose, we sequenced the PrD of the URE2 gene in a library of 18 different strains of S. cerevisiae, chosen on the basis of geographic localization (these strains were kindly given by Prof M. Aigle, IGGC, Bordeaux). Several strains were isolated in a bakery at Chrisoles (France). One strain was used to produce beer from the millet and was isolated in Djibouti, Africa. One other strain was found in a rotten wood and several other were used for wine production. None of these strains is pathogenic. The 18-nucleotide sequences fall into two groups. A first one, including 16 sequences, shows no differences with the laboratory strain, and a second one (composed of the 2 last sequences) shows one difference (a G or an A substitution at position 68) that leads to the replacement of an asparagine by a serine. Thus, intraspecies variation is minor compared with interspecies variation.

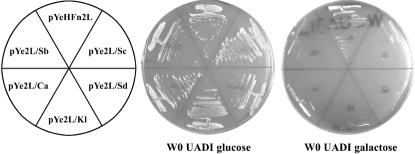

The Functional Activity of Ure2p Is Well Conserved through Evolution

To test if the function of the six heterologous URE2 genes has been conserved during evolution, a complementation test was carried out. DNA fragments were PCR amplified and cloned into multicopy expression vectors, in which the insert is expressed under the control of the GAL1 promoter. Those constructions were used to transform the haploid Sacccharomyces cerevisiae strain AF36 deleted for the URE2 gene. The vector and the URE2Sc fragment were used as controls. After a 48-h induction on a galactose (Gal) medium, each transformed strain was streaked on both glucose (Glu) + USA and Gal + USA medium. Results are shown Figure 2. As expected, all the strains were able to grow on Glu + USA medium because the absence of the URE2 function does not prevent the uptake of USA. For the AF36 strain harboring the pYeHFn2L plasmid, this function is still defective on galactose medium allowing the growth on USA.

Figure 2.

Complementation assays. A strain deleted for URE2 (AF36) was transformed by the different plasmids allowing the overexpression of orthologous URE2. The different plasmids used are indicated on the left. After a 2-d growth on galactose medium, the transformants were streaked on both glucose and galactose medium, supplemented with the indicated nutriments (U, USA; A, adenine; D, histidine; I, tryptophan). The Petri dishes were observed after 4 d at 30°C. The expression of a functional Ure2p protein on galactose makes the strain unable to grow on USA medium.

On the contrary, the strain expressing the Sc Ure2p protein is blocked on Gal + USA as a wild-type strain is. The expression of the four heterologous proteins, Sp, Su, Kl, and Ca, prevents the strain AF36 to grow on a Gal + USA medium, showing that those proteins can functionally substitute for the Sc Ure2p when overexpressed. This indicates that the cellular activity supported by the C-terminal domain in Sc is conserved trough evolution. We have noticed that, when the Kl and Ca genes are expressed, small colonies began to appear after at least 4 d of growth. That means that complementation is weaker with these two genes. The Spb1 and Spb2 genes have been tested together or individually, but in all the cases the strains always grew on Gal + USA (our unpublished results), indicating the incapacity for these ORFs to sustain the wild-type phenotype.

Properties of the N-terminal Domain

The URE2Sc gene can be divided into two domains, a C-terminal domain that contains the functional activity (from the Met codon at position 94 to the stop codon) and the N-terminal domain (from the Met at position 1 to the Asp at position 93). This PrD, whose particular composition has already been underlined, is responsible for the induction and the propagation of the prion state. It has been reported that overexpression of this domain has a dramatic effect on [URE3] appearance (Masison and Wickner, 1995; Maddelein and Wickner, 1999). This modular composition is also found for another yeast prion protein: Sup35p (Ter-Avanesyan et al., 1994; Derkatch et al., 1996). In this protein, the prion properties are also enciphered in an amino terminal domain that is dispensable for the cellular function.

A putative PrD very similar to that of the Sc gene is found in all the URE2 genes studied, except for the Spb genes. Interestingly, they present a high variability. Some of them bear a shorter (Su) or longer (Sp) one. In some cases a polyglutamine sequence is found instead of polyasparagine stretches (Kl), and in one case, (Ca), the PrD sequence is so divergent that its comparison is a little bit tricky (Figure 1). Thus, we wanted to test whether those N-terminal domains have conserved the ability to induce [URE3] by acting in trans on the URE2Sc gene.

Each sequence was PCR-amplified and cloned into the previous expression vectors. The constructs were used to transform the CC30 strain containing the URE2Sc gene and the number of Usa+ colonies that appeared after overexpression of the heterologous PrD was determined. The induction upon expression of PrDSc is 1000-fold above the spontaneous rate (Table 3). This confirms that residues from 1 to 93 possess a very high capacity to induce [URE3], as expected.

Table 3.

Induction of Usa+ colonies upon overproduction of the PrDs

| Plasmid | USA+ per 106 cells |

|---|---|

| pYeHFn2T | 25 |

| PYe2T/ScΔC | 11,700 |

| PYe2T/SpΔC | 400 |

| PYe2T/SuΔC | 13,000 |

| PYe2T/KΔC | 100 |

| PYe2T/CaΔC | 100 |

The haploid CC30 strain was transformed with the different plasmids that permit the overproduction of the PrD of the heterologous Ure2p protein. The transformed strains were grown on minimal galactose medium for 48 h to induce the over expression. Finally, 106, 105, and 104 cells were plated on synthetic glucose medium containing USA. The average number of Usa+ colonies for 106 living cells is shown.

PrDSp is very close in term of sequence to PrDSc. Although it is richer in Asn, the overexpression of PrDSp is less effective with a 200-fold induction. The PrDSu is as efficient as PrDSc, with a 1000-fold increase in the rising of [URE3]. However, this PrD is more distant from PrDSc in term of sequence homology than PrDSp.

PrDKl and PrDCa are also rich in Gln and Asn residues, but have a poor sequence homology with PrDSc. Overexpression of these two heterologous domains have no significant effect on [URE3] induction, with an average of four-fold. If these sequences induce [URE3], this effect is so subtle that it cannot be measured by this way.

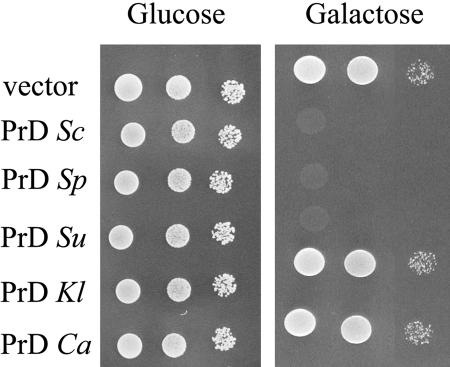

The PrD of S. cerevisiae has not only the inducing capacity, but its overexpression has also the capability to cure a [URE3] strain (Edskes et al., 1999). We have transformed the [URE3] strain, AB34, with the set of N-terminus to examine their effect on preexisting [URE3Sc]. Because the transformation procedure may lead to a loss of [URE3], only transformed colonies, which have retained the [URE3] phenotype are kept.

Twelve independent clones were grown in parallel in Gal or Glu media for 72 h, transferred on glucose to block the expression of the N-terminus, and then tested for the Usa phenotype on glucose. At this stage, the growth capacity indicates the maintenance of [URE3] during overexpression of heterologous PrD. In all the cases, the 12 clones behave in the same way, and only one clone is represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Curing effect of the PrDs. The ability of the AB34 [URE3Sc] strain to grow on USA medium was tested after overexpression of the different PrDs. After selection, overexpression of the Prd was allowed (growth on galactose medium for 48 h) or repressed (growth on glucose medium), and the cells were streaked on Glu + USA. For each construct, the result is shown for one clone with two 10-fold dilutions.

When the [URE3] cells were grown on Glu, whatever the plasmid used, the repressing conditions should allow the maintenance of [URE3]. This is fortunately the case, because all tested transformants remained Usa+ (Figure 3). This was also observed when the cells transformed by the control vector were grown on Gal. This indicates that the [URE3] phenotype is mitotically stable on both carbon sources. The curing effect, expected with PrDSc, was also observed upon overepression of PrDSp and PrDSu but not with PrDKl and PrDCa.

PrDSp and PrDSu, the two closest species to Sc, have thus retained all the properties of the S. cerevisiae PrD. On the contrary, PrDKl and PrDCa are devoid of any inducing properties but also are incapable to promote the elimination of a preexisting [URE3]. Interestingly, these two properties seem to be strictly linked.

[URE3] Initiation in S. cerevisiae for the Heterologous Ure2p Is Not Conserved

Because no genetic tools are available in the various heterologous yeasts, we took advantage of the ability of the Sp, Su, Kl, and Ca proteins to complement a Sc strain deficient for the URE2 function. Each foreign Ure2p was overexpressed in the Δure2Sc strain to avoid any cross-reaction with the endogenous Ure2p. The transformed strains were then plated on Gal + USA to select the Usa+ colonies that may arise either from the conversion into the [URE3] state or from any other events that leads to the loss of the URE2 function. The number of Usa+ cells was first measured and Usa+ colonies were then tested for the [URE3] character (Table 4). As expected for the URE2Sc gene, a high number of Usa+ colonies were obtained. This is consistent with the fact that overexpression of the full-length protein increases the appearance of [URE3] (Masison and Wickner, 1995, 1999). The majority of the Usa+ cells fulfilled three criteria: 1) curable in presence of 5 mM guanidium chloride; 2) dominant when crossed with the wild-type CC30 strain; and 3) nonmendelian segregation of the diploids arisen from the cross with CC30.

Table 4.

Prion properties of the orthologous Ure2p

| Plasmid | USA+ per 106 cells |

|---|---|

| PYeHFn2L/Sc | 3600 |

| PYeHFn2L/Sp | 13 |

| PYeHFn2L/Su | 3400 |

| PYeHFn2L/K | <0.5 |

| PYeHFn2L/Ca | <0.1 |

The haploid AF36 strain (Δure2) was transformed with the set of plasmids expressing the orthologous Ure2p protein. The transformed strains were grown on minimal galactose medium for 48 h and 106, 105, and 104 cells were plated on synthetic galactose medium containing USA. The average number of Usa+ colonies for 106 living cells is indicated.

Some Usa+ colonies, however, appeared to be due to plasmid recombination and subsequently, to the loss of the Ure2p function. In that case, the observed phenotype was not curable and was recessive as expected.

When the URE2Su ORF was tested by this approach, the number of Usa+ clones that appeared was found to be quite similar to that of URE2Sc. Consistent with this observation, it was possible to isolate a Usa+ clone with the genetic characteristics of the genuine [URE3]. This result is in agreement with the capacity of the putative URE2Su PrD to be indeed a real prion-inducing domain.

Although the prion-inducing capacity is also found in the N-terminal part of URE2Sp, a small number of Usa+ clones arose from the overexpression of URE2Sp. Moreover, when the clones were genetically tested, they did not fulfill the 3 prion criteria. Finally, all the Usa+ clones tested were demonstrated to be due to the rearrangement of the plasmid. The URE2Sp ORF appears thus to be resistant to the “prionization” process, although it contains a PrD that promote in trans the prionization of URE2Sc.

When the K. lactis and C. albicans URE2 ORFs were overexpressed, Usa+ colonies arose at a very low frequency. The genetic and molecular properties of these clones demonstrated that they did correspond to a recombination of the plasmid in all the cases.

One could not rule out the possibility that the conversion into the [URE3] state would arrive at a very low frequency. To increase the probability for one cell to exhibit [URE3], we coexpressed the full-length protein and the corresponding PrD. The transformants harboring both plasmids were analyzed in the same way. However, this coexpression did not enhance the rate of [URE3] as it does for S. cerevisiae (our unpublished results). We were therefore not able to isolate any S. cerevisiae strain containing [URE3Sp], [URE3Kl], or [URE3Ca].

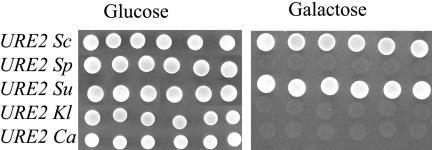

Existence of a Species Barrier to Prion Propagation

We found that the prion initiation failed for most of the heterologous Ure2p expressed in S. cerevisiae. We wondered if the foreign proteins were nevertheless able to affect a preexisting [URE3Sc] and thus could support prion propagation or inhibit the propagation of [URE3Sc]. For that purpose the strain AF36 was transformed by each expression plasmid and crossed with the [URE3Sc] strain AB34. Six diploids were selected on Glu + USA medium and grown for 48 h on galactose to induce protein expression. At this stage, each diploid was tested in parallel on Gal + USA and Glu + USA media. Three cases may be imagined.

1. If a species barrier prevents the transmission of [URE3Sc] to the heterologous Ure2p, then, the heterologous protein would not interact at all with the endogenous [URE3Sc]. Its production would mask the prion phenotype (absence of growth on Gal + USA medium). Switching off its transcription would revert the phenotype to the original [URE3Sc]. The diploid cells should grow on Glu + USA medium.

2. In the second scenario, [URE3Sc] has the capability to switch the heterologous URE2 from an active form to the prion state. In this absence of such species barrier, the conversion of the heterologous protein would permit the growth on the Gal + USA medium. In that case, stopping the expression of the heterologous Ure2p by plating on Glu + USA would not interfere with the propagation of [URE3Sc] and the growth on Glu + USA would be observed.

3. A third result can be obtained with an absence of growth both on Glu and Gal + USA media. Indeed the heterologous URE2 ORF could behave as an “antiprion” allele and could cure [URE3Sc]. This effect is found with a mutant of the SUP35 gene that is unable to be converted into the prion shape, but also leads to the loss of the preexisting [PSI+] phenotype (Doel et al., 1994; Kochneva-Pervukhova et al., 1998). It has been also shown that overexpression of the full-length Ure2pSc slightly cures [URE3] (Edskes et al., 1999; Fernandez-Bellot et al., 2000). One could imagine that the interaction between the heterologous Ure2p and Ure2pSc could have such effect rather than leading to a conversion into [URE3].

The control consisted in expressing Ure2pSc. All the diploids remained [URE3] on both Glu and Gal, indicating that the curing effect is low (Figure 4). This result was also found when Ure2pSu is overexpressed, leading to the conclusion that Ure2pSu can be inactivated through [URE3Sc]. On the other hand, the cells overexpressing Ure2p Kl and Ca failed to grow on Galactose + USA, but grew on Glucose + USA, indicating that each Ure2p species behaves independently from [URE3Sc]. This result is consistent with the incapability of the N-terminal domain of these proteins to induce [URE3]. Surprisingly, Ure2p Sp behaves in the same way, although this protein possesses a fully functional PrD.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the species barrier. The AF36 strain (deleted for URE2) expressing Sc or heterologous URE2 ORFs under the control of a Gal promoter was crossed with the strain AB34 [URE3]. Diploids were grown on galactose medium for 48 h and tested on Glu + USA and Gal + USA.

The Ure2pSu is the only heterologous protein that may be inactivated in S. cerevisiae by a prion process. It was therefore also interesting to test the existence of a species barrier between [URE3Su] and Ure2pSc. The [URE3Su] strain, previously isolated, was crossed with the wild-type strain CC30. The diploids obtained were plated on a GAL + USA medium to test the dominance/recessivity of the phenotype. All the diploids were Usa+ indicating that there is a transfer of the prion state between Ure2pSu and Ure2pSc. When platted in a GLU + USA medium, the strain remains Usa+, although Ure2pSu is no more expressed (our unpublished results). This indicates that the self-inactivation initially found for Ure2pSu is now transmitted to Ure2pSc and that no species barrier exist between these two proteins, whatever the prion inactivation initially concerns one or the other protein.

DISCUSSION

The two well-characterized yeast prions, Ure2p and Sup35p, have a similar N-terminal domain that retains all the prion properties. The PrD of Sup35p, however, differs from its Ure2p counterpart by the presence of five imperfect oligopeptide repeats (Kushnirov et al., 1988), a feature shared with the mammalian prion determinant PrP (Kretzschmar et al., 1986). Deletion or expansion of the repeats inhibits or increases the conversion to [PSI+], respectively. Transmission of the prion [PSI+] to other species has been extensively studied but little is known in the case of [URE3] because only an article is related to this subject (Edskes and Wickner, 2002). In an attempt to better understand the molecular basis of [URE3] induction and propagation and the role of this phenotype in the yeast life, we have cloned five URE2 genes from various yeast species. The sequence analysis has revealed that the PrD is present in all the ORFs but the two S. pombe URE2 genes.

The functional domain shows a remarkable similarity in term of sequence alignment in the group of closely related yeasts (Sc, Sp, and Su). This is consistent with the conservation of the function in vivo, because the overproduction of all but the two S. pombe Ure2p proteins leads to the complementation of a S cerevisiae strain deficient for the URE2 function. The two S. pombe sequences are more divergent and the region between amino acids 267 and 295 is absent. The crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of Ure2p has been elucidated and this region is of particular interest. The overall structure of Ure2p (95–354) is similar to that of members of the glutathione-S-transferase superfamily, to the exception of the addition of the cap (Arg-267 to Pro298; Bousset et al., 2001) or clip (Glu-273 to Phe-294; Umland et al., 2001) region. This region has been proposed to be responsible of the specificity of Ure2p or to be the site of interaction between Ure2p and its cellular partners. Thus, its absence within the S. pombe sequences could account for the loss of function of the two proteins. Interestingly, the absence of the clip structure correlates with the absence of PrD. The two S. pombe proteins have thus to be considered as paralogous genes in the URE2 group. This also indicates that the URE2 gene is conserved only in a subfamily of the broader yeast family. The data collected from the Genolevure project, although incomplete, indicate that URE2 gene is not systematically present in the genome of the partially sequenced hemiascomycetes. Because the presence or the absence of the PrD and the clip structure together seems to be correlated, it may indicate that both are required for the cellular function of Ure2p or for the prionization of the protein.

When the properties of the five putative PrD of Ure2p are analyzed, we find that it follows the evolution pressure with PrDSc, PrDSp, and PrDSu capable of [URE3Sc] induction and curing. It is noteworthy that PrDSp is less efficient than its Sc homologue. It raises the question of which sequence modification could be responsible for this effect. It is tempting to speculate that this is due to the N79D change because asparagine to aspartate mutations were shown to have a drastic effect on [PSI+] induction (Osherovich and Weissman, 2001). However, this mutation is also present in the PrDSu sequence with no dramatic consequences. Another striking feature of this PrDSp domain is the expansion of the asparagine track, which is generally in favor to protein aggregation. Indeed, neurodegenerative diseases are associated with the polyglutamine stretch that leads to formation of amyloid fibrils and is correlated with pathogenesis. However, the existence of a deletion of seven asparagine residues at the same position in PrDSu, without having an inhibitory effect, is against a simple explanation that directly links [URE3] appearance to the number of asparagines and glutamine amino acids.

PrDKl and PrDCa lose these inducing and curing properties. This incapacity may reflect two different processes. One evident possibility is that these sequences are really devoid of any prionization properties. The second possibility is linked to the species barrier. The species barrier stricto-senso represents the capacity for a replicative agent isolated in one species to propagate in a different species. For the yeast prion, the same expression has been used to describe a different mechanism. The species barrier represents the possibility for a protein cloned in a species A and expressed in a species B, to be converted by its orthologous into an inactive prion isoform. This phenomenon as been initially studied by Santoso et al. (2000) for orthologous SUP35 alleles. Interestingly, the N-terminal domains of Ure2pKl and Ure2pCa are Q/N-rich as the PrDs are. The three subdomains conserved in the Saccharomyces species completely disappear in C. albicans and are replaced by a Q/N-rich region. In K. lactis, only the first subdomain can be identified, the two others being replaced by a Q-rich sequence. The invasion of the three conserved motifs by the Q/N-rich subdomains A and B is clearly correlated with the incapacity of these N-terminal regions to promote the prionization in S. cerevisiae. This result is consistent with the study of Resende et al. (2002), who have studied the protein encoded by the C. albicans SUP35 gene. This protein is characterized by the presence of poly(Gln) stretches and is unable to induce or sustain the [PSI+] phenotype.

We have then examined the prionization properties of each full-length Ure2p orthologous. We have tested their ability to be spontaneously converted into the prion form in a ΔURE2Sc strain or in a wild-type strain (cis-conversion). We have also analyzed the trans-conversion induced by a preexisting [URE3Sc] element and finally, measured their capacity to cure a preexisting [URE3Sc] when overexpressed.

We found that Ure2pKl and Ure2pCa cannot initiate a prionization process, neither in cis nor in trans. Also, overexpression of these Ure2p orthologues does not lead to the cure of a preexisting [URE3Sc]. Despite Edskes and Wickner (2002) reported that they could cure [URE3] by overexpressing all Ure2p orthologues, except with Saccharomyces and C. lipolytica, they did not expressly said so with K. lactis ortholog, which does not appear in the result table 5 (Edskes and Wickner, 2002). Thus we cannot definitely conclude whether our results are consistent or not with theirs, but that point might be interesting to discuss. Surprisingly, it was also impossible to isolate a [URE3Sp] strain whatever the method used (spontaneous conversion in a ΔURE2Sc strain or in a wild-type strain, conversion induced by [URE3Sc]). This result is in contradiction with previous results (Edskes and Wickner, 2002) that mentioned that Ure2pSu may induce [URE3Sc] in a wild-type strain. The differences in the genetic background of the yeast strains used in both studies may explain this discrepancy. The S. paradoxus PrD expressed in trans promotes the prionization of Ure2pSc but fails to act in the same way in cis. Moreover, the expression of both [URE3Sc] and Ure2pSp shows that this protein is resistant to the prionization by a preexisting propagon. An explanation for this observation could be that the full-length protein exists in such a conformational state that it inhibits the activity of the PrD. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that physical interactions between the N- and C-terminal parts of the Ure2p protein have already been reported (Fernandez-Bellot et al., 1999). Moreover, the confrontation between experimental results that have identified C-terminal mutations and deletions that influence [URE3] induction and the crystal structure of Ure2p leads to the growing idea that the prion property of PrD is modulated by interaction between the two domains (Maddelein and Wickner, 1999; Fernandez-Bellot et al., 2000; Moriyama et al., 2000). One possibility is that the longer asparagine stretch could stick the PrD in an inefficient state. These results also demonstrated that the characterization of any PrD based on its activity in trans might lead to some misinterpretation (one could consider the N-terminal domain of URESp as a PrD, but in a wild-type context, it does not give rise to the inactivation of the protein in a prion-like mechanism.)

The inducing property of PrDSu is associated with the ability to acquire a prion conformation in S. cerevisiae. Moreover, no species barrier occurs when the Ure2pSu protein is expressed in presence of [URE3Sc] and vice versa, indicating that the two heterologous proteins fully interact each other.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that the regulatory functions of Ure2p are well conserved in the hemyascomycete phylum. The functional approach (corresponding to the expression of the orthologous URE2 ORFs in S. cerevisiae) clearly shows the absence of prionization capabilities for several orthologous proteins. This incapability has now to be confirmed by genetic approaches in these species. If it were, it would demonstrate that the prion properties of Ure2p are not linked to the cellular functions of this protein because not maintained during the evolution. Alternatively, the heterologous Ure2p could be incapable of interacting with a S. cerevisiae partner that is essential to prion induction. One candidate is Hsp104p that has been proposed to be essential to the propagation of the two most studied yeast prions (Chernoff et al., 1995; Moriyama et al., 2000). To test these two hypotheses, it would be useful to analyze the behavior of Ure2p, in each organism, as it has been done with the Sup35pKl protein in a K. lactis strain (Nakayashiki et al., 2001). The Ure2pSp possesses a functional prion-inducing domain inactive in cis, but not in trans. The prionization properties are thus hidden in standard conditions. This finding supports the idea that the prion capacities of the N-terminal region of Ure2p are not the main roles played by this domain. It suggests that this effect is rather an accidental consequence of an unusual amino acid bias. It has been recently demonstrated that amyloid formation of proteins not associated with any disease leads to early species that are highly cytotoxic (Bucciantini et al., 2002). As Ure2p, in vitro, adopt easily an amyloid structure (Thual et al., 1999), [URE3] could be an alternative way to inactivate such intermediates. Biochemical as well as cellular and genetic investigations are now required to establish the relation ship between prionization, aggregation, and amyloidogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. Clancampbell for looking over the English. The work was supported by grants to C.C. from Action Concertée Coordonnée Science du Vivant no. 10 (9510001) and EC Contract (no. BI104–98-6045, Maintenance and transmission of yeast prions: a model system).

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0007. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0007.

Abbreviations used: USA, ureidosuccinate; Gal, galactose; Glu, glucose; Sc, Sacccharomyces cerevisiae; Sp, Sacccharomyces paradoxus; Su, Sacccharomyces uvarum; Kl, Kluyveromyces lactis; Ca, Candida albicans; Spb, Schizosaccharomyces pombe; PrD, prion domain

References

- Aigle, M., and Lacroute, F. (1975). Genetical aspects of [URE3], a non-mitochondrial, cytoplasmically inherited mutation in yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 136, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D.J. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousset, L., Belrhali, H., Janin, J., Melki, R., and Morera, S. (2001). Structure of the globular region of the prion protein Ure2 from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Structure 9, 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciantini, M. et al. (2002). Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature 416, 507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff, Y.O., Lindquist, S.L., Ono, B., Inge, V.S., and Liebman, S.W. (1995). Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [psi+]. Science 268, 880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullin, C., and Minvielle, S.L. (1994). Multipurpose vectors designed for the fast generation of N- or C-terminal epitope-tagged proteins. Yeast 10, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch, I.L., Bradley, M.E., Hong, J.Y., and Liebman, S.W. (2001). Prions affect the appearance of other prions: the story of [PIN(+)]. Cell 106, 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch, I.L., Bradley, M.E., Masse, S.V., Zadorsky, S.P., Polozkov, G.V., Inge-Vechtomov, S.G., and Liebman, S.W. (2000). Dependence and independence of [PSI(+)] and [PIN(+)]: a two-prion system in yeast? EMBO J. 19, 1942–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch, I.L., Bradley, M.E., Zhou, P., Chernoff, Y.O., and Liebman, S.W. (1997). Genetic and environmental factors affecting the de novo appearance of the [PSI+] prion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 147, 507–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch, I.L., Chernoff, Y.O., Kushnirov, V.V., Inge, V.S., and Liebman, S.W. (1996). Genesis and variability of [PSI] prion factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 144, 1375–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doel, S.M., McCready, S.J., Nierras, C.R., and Cox, B.S. (1994). The dominant PNM2-mutation which eliminates the psi factor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the result of a missense mutation in the SUP35 gene. Genetics 137, 659–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edskes, H.K., Gray, V.T., and Wickner, R.B. (1999). The [URE3] prion is an aggregated form of Ure2p that can be cured by overexpression of Ure2p fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1498–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edskes, H.K., and Wickner, R.B. (2002). Conservation of a portion of the S. cerevisiae Ure2p prion domain that interacts with the full-length protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99(Suppl 4), 16384–16391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann, H. (2000). Genolevures—a novel approach to `evolutionary genomics.' FEBS Lett. 487, 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Bellot, E., Guillemet, E., Baudin-Baillieu, A., Gaumer, S., Komar, A.A., and Cullin, C. (1999). Characterization of the interaction domains of Ure2p, a prion-like protein of yeast. Biochem. J. 338, 403–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Bellot, E., Guillemet, E., and Cullin, C. (2000). The yeast prion [URE3] can be greatly induced by a functional mutated URE2 allele. EMBO J. 19, 3215–3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz, D.G., St. Jean, A., Woods, R.A., and Schiestl, R.H. (1992). Improved method for hight***** efficiency transformation of intact cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochneva-Pervukhova, N.V., Paushkin, S.V., Kushnirov, V.V., Cox, B.S., Tuite, M.F., and Ter-Avanesyan, M.D. (1998). Mechanism of inhibition of Psi+ prion determinant propagation by a mutation of the N-terminus of the yeast Sup35 protein. EMBO J. 17, 5805–5810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar, H.A., Stowring, L.E., Westaway, D., Stubblebine, W.H., Prusiner, S.B., and Dearmond, S.J. (1986). Molecular cloning of a human prion protein cDNA. DNA 5, 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirov, V.V., Kochneva-Pervukhova, N.V., Chechenova, M.B., Frolova, N.S., and Ter-Avanesyan, M.D. (2000). Prion properties of the Sup35 protein of yeast Pichia methanolica. EMBO J. 19, 324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirov, V.V., Ter, A.M., Telckov, M.V., Surguchov, A.P., Smirnov, V.N., and Inge, V.S. (1988). Nucleotide sequence of the SUP2 (SUP35) gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 66, 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroute, F. (1971). Non-Mendelian mutation allowing ureidosuccinic acid uptake in yeast. J. Bacteriol. 106, 519–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddelein, M.L., and Wickner, R.B. (1999). Two prion-inducing regions of Ure2p are nonoverlapping. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 4516–4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masison, D., and Wickner, R.B. (1995). Prion-inducing domain of yeast ure2p and protease resistance of ure2p in prion-containing cells. Science 270, 93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelitsch, M.D., and Weissman, J.S. (2000). A census of glutamine/asparagine-rich regions: implications for their conserved function and the prediction of novel prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11910–11915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama, H., Edskes, H.K., and Wickner, R.B. (2000). [URE3] prion propagation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: requirement for chaperone Hsp104 and curing by overexpressed chaperone Ydj1p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 8916–8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayashiki, T., Ebihara, K., Bannai, H., and Nakamura, Y. (2001). Yeast [PSI+] “prions” that are crosstransmissible and susceptible beyond a species barrier through a quasi-prion state. Mol. Cell 7, 1121–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osherovich, L.Z., and Weissman, J.S. (2001). Multiple Gln/Asn-rich prion domains confer susceptibility to induction of the yeast [PSI(+)] prion. Cell 106, 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resende, C., Parham, S.N., Tinsley, C., Ferreira, P., Duarte, J.A., and Tuite, M.F. (2002). The Candida albicans Sup35p protein (CaSup35p): function, prion-like behaviour and an associated polyglutamine length polymorphism. Microbiology 148, 1049–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoso, A., Chien, P., Osherovich, L.Z., and Weissman, J.S. (2000). Molecular basis of a yeast prion species barrier. Cell 100, 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer, N., and Lindquist, S. (2000). Rnq 1, an epigenetic modifier of protein function in yeast. Mol. Cell 5, 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter-Avanesyan, M.D., Dagkesamanskaya, A.R., Kushnirov, V.V., and Smirnov, V.N. (1994). The SUP35 omnipotent suppressor gene is involved in the maintenance of the non-Mendelian determinant [psi+] in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 137, 671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thual, C., Komar, A.A., Bousset, L., Fernandez-Bellot, E., Cullin, C., and Melki, R. (1999). Structural characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae prion-like protein Ure2. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13666–13674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umland, T.C., Taylor, K.L., Rhee, S., Wickner, R.B., and Davies, D.R. (2001). The crystal structure of the nitrogen regulation fragment of the yeast prion protein Ure2p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 1459–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner, R.B. (1994). [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 264, 566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]