Abstract

This study was carried out to determine the effect of protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) activation on the pulmonary chemoreflex responses and on the sensitivity of isolated rat vagal pulmonary chemosensitive neurons. In anaesthetized, spontaneously breathing rats, intratracheal instillation of trypsin (0.8 mg ml−1, 0.1 ml), an endogenous agonist of PAR2, significantly amplified the capsaicin-induced pulmonary chemoreflex responses. The enhanced responses were completely abolished by perineural capsaicin treatment of both cervical vagi, suggesting the involvement of pulmonary C-fibre afferents. In patch-clamp recording experiments, pretreatment with trypsin (0.1 μm, 2 min) potentiated the capsaicin-induced whole-cell inward current in isolated pulmonary sensory neurons. The potentiating effect of trypsin was mimicked by PAR2-activating peptide (PAR2-AP) in a concentration-dependent manner. PAR2-AP pretreatment (100 μm, 2 min) also markedly enhanced the acid-evoked inward currents in these sensory neurons. Furthermore, the sensitizing effect of PAR2 was completely abolished by pretreatment with either U73122 (1 μm, 4 min), a phospholipase C inhibitor, or chelerythrine (10 μm, 4 min), a protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor. In summary, our results have demonstrated that activation of PAR2 upregulates the pulmonary chemoreflex sensitivity in vivo and the excitability of isolated pulmonary chemosensitive neurons in vitro, and this effect of PAR2 activation was mediated through the PKC-dependent transduction pathway. These results further suggest that the hypersensitivity of these neurons may play a part in the development of airway hyper-responsiveness resulting from PAR2 activation.

The afferent activities that arise from sensory terminals located in the airways and lungs are conducted almost exclusively by vagus nerves and their branches (Paintal, 1973; Widdicombe, 1982). Cell bodies of these sensory nerves reside in two adjacent but distinct anatomical structures, the nodose and intracranial jugular ganglia. It has been shown that >75% of vagal bronchopulmonary afferents are non-myelinated C-fibres that exhibit exquisite chemosensitivity (Agostoni et al. 1957). The importance of these C-fibre afferents in regulating the cardiorespiratory functions under both normal and abnormal physiological conditions has been well documented (Paintal, 1973; Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984; Lee & Pisarri, 2001; Lee & Undem, 2005).

Protease-activated receptors (PARs) are a family of G-protein-coupled, seven-transmembrane-domain receptors that are activated by proteolysis (Déry et al. 1998; Macfarlane et al. 2001; Ossovskaya & Bunnett, 2004). Certain proteases are known to cleave PARs within the extracellular N-terminus to expose tethered ligand domains that bind and activate the cleaved receptors. Four subtypes of PARs (PAR1 to PAR4) have been identified. PAR1 and PAR3 are both preferentially cleaved by thrombin, PAR2 by trypsin and tryptase, whereas PAR4 is activated by trypsin and thrombin. All PARs, except PAR3, can be selectively activated by the short synthetic peptide that mimics the tethered region of the receptor (Macfarlane et al. 2001; Vergnolle et al. 2001b; Ossovskaya & Bunnett, 2004).

PAR2 is expressed in a variety of cells in the airways and lungs including epithelial cells, airway smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells and fibroblasts, as well as inflammatory cells such as mast cells, neutrophils and macrophages (Howells et al. 1997; D'Andrea et al. 1998; Cocks et al. 1999; Akers et al. 2000; Reed & Kita, 2004). It has been recently suggested that activation of PAR2 by endogenous or exogenous agonists such as mast cell tryptase, trypsin-like proteases and some house mite allergens contributes to airway inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness, the hallmarks of certain airway inflammatory diseases such as asthma (Ricciardolo et al. 2000; Chambers et al. 2001; Schmidlin et al. 2002; Barrios et al. 2003; Ebeling et al. 2005), and an involvement of a neurogenic mechanism caused by the activation of pulmonary C-fibre afferents has been postulated (Ricciardolo et al. 2000; Cocks & Moffatt, 2001; Barrios et al. 2003). However, the effect of PAR2 activation on these pulmonary chemosensitive- (C-) neurons remains unclear. The present study was therefore carried out: (1) to determine whether activation of PAR2 enhances the sensitivity of the pulmonary chemoreflex, which is known to be elicited by stimulation of pulmonary C-fibre afferents (Lee & Pisarri, 2001), in anaesthetized and spontaneously breathing rats; (2) to determine whether this enhancing effect of PAR2 activation is caused by an increase in sensitivity of the vagal pulmonary sensory neurons; and (3) if so, to investigate the intracellular signalling pathway involved in the sensitizing effect caused by the PAR2 activation.

Methods

The procedures described below were performed in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health and were also approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Measurements of cardiorespiratory responses

Sprague-Dawley rats (330–415 g) were initially anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of α-chloralose (100 mg kg−1) and urethane (500 mg kg−1) dissolved in a 2% borax solution; supplemental doses of α-chloralose (∼10 mg kg−1 h−1) and urethane (∼50 mg kg−1 h−1) were injected intravenously (i.v.) to maintain abolition of pain reflexes elicited by paw-pinch. The right femoral artery and the left jugular vein were cannulated for recording arterial blood pressure (ABP) and injection of chemical agents, respectively. The jugular venous catheter was advanced until its tip was positioned just above the right atrium. The volume of each bolus injection was 0.1 ml, which was first injected into the catheter (∼0.2 ml) and then flushed into the circulation by an injection of 0.3 ml saline. A short tracheal cannula was inserted after a tracheotomy, and tracheal pressure (Pt) was measured (Validyne MP 45-28) via a side-port of the tracheal cannula. Body temperature was maintained at ∼36°C by means of a heating pad placed under the animal lying in a supine position. At the end of the experiment, the animal was killed by an injection of KCl (200 mg kg−1; i.v.).

Rats breathed spontaneously via the tracheal cannula. Respiratory flow was measured with a heated pneumotachograph and a differential pressure transducer (Validyne MP 45-14), and integrated to give tidal volume (VT). Respiratory frequency (f), expiratory duration (TE), VT, minute ventilation, ABP and heart rate were analysed (Biocybernetics TS-100) on a breath-by-breath basis by an online computer.

Labelling vagal pulmonary sensory neurons with DiI

Vagal pulmonary sensory neurons were identified by retrograde labelling from the lungs by using the fluorescent tracer DiI as previously described (Kwong & Lee, 2002). Briefly, young adult Sprague-Dawley rats (∼160 g) were anaesthetized with an i.p. injection of pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1) and intubated with a polyethylene catheter (PE 150) with its tip positioned in the trachea above the thoracic inlet. DiI was initially sonicated and dissolved in ethanol, diluted in saline (1% ethanol v/v), and then instilled into the lungs (0.2 mg ml−1; 0.2 ml × 2) with the animal's head tilted upward at ∼30 deg.

Isolation and culture of nodose and jugular ganglion neurons

After 7–10 days, an interval previously determined to be sufficient for DiI to diffuse to the cell body, the rats were anaesthetized by halothane inhalation and decapitated. The head was immediately immersed in ice-cold Hank's balanced salt solution. Nodose and jugular ganglia were extracted under a dissecting microscope and placed in ice-cold Dulbecco's minimal essential medium/F12 (DMEM/F12) solution. Each ganglion was desheathed, cut into ∼10 pieces, placed in 0.125% type IV collagenase, and incubated for 1 h in 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. The ganglion suspension was centrifuged (150 g, 5 min) and supernatant-aspirated. The cell pellet was resuspended in 0.05% trypsin in Hanks' balanced salt solution for 5 min and centrifuged (150 g, 5 min); the pellet was then resuspended in a modified DMEM/F12 solution (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 u ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, and 100 μm MEM non-essential amino acids) and gently triturated with a small-bore fire-polished Pasteur pipette. The dispersed cell suspension was centrifuged (500 g, 8 min) through a layer of 15% bovine serum albumin to separate the cells from the myelin debris. The pellets were resuspended in the modified DMEM/F12 solution supplemented with 50 ng ml−1 2.5S nerve growth factor, plated onto poly l-lysine-coated glass coverslips, and then incubated overnight (5% CO2 in air at 37°C).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell perforated patch-clamp recordings were carried out as previously described (Gu et al. 2005). Briefly, the coverslip containing the attached cells was placed in the centre of a small recording chamber (0.2 ml) that was perfused by gravity-feed (VC-6 perfusion valve controller; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) with standard extracellular solution (ECS). The chemical stimulants were applied by a pressure-driven drug delivery system (ALA-VM8; ALA Scientific Instruments, Westbury, NY, USA), with its tip positioned to ensure that the cell was fully within the stream of the injectate. Recordings were made in the whole-cell perforated-patch configuration (50 μg ml−1 gramicidin) using Axopatch 200B/pCLAMP 9.0 (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). The data were acquired at 5 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. The series resistance was usually in the range of 4–8 MΩ and was not compensated. The resting membrane potential was held at −70 mV. The experiments were performed at room temperature (∼22°C).

Experimental protocols

Three series of experiments were carried out.

Study series 1

The effect of airway exposure of trypsin, an activator of PAR2, on pulmonary chemoreflex sensitivity was determined in anaesthetized and spontaneously breathing rats. Response to right atrial bolus injection of capsaicin (0.5 μg kg−1), a potent and selective stimulant of C-fibres, was tested before and at different time points after the trypsin instillation (0.8 mg ml−1, 0.1 ml). In a separate group of rats, the role of vagal C-fibre afferents in the effect of trypsin on pulmonary chemoreflex sensitivity was evaluated after perineural capsaicin treatment (PNCT) of both vagi, which produced a selective and reversible blockade of the C-fibre conduction in the vagus nerve. PNCT was applied as previously described (Lin & Lee, 2002). Briefly, cotton strips soaked in capsaicin solution (250 μg ml−1) were wrapped around a 2–3 mm segment of the isolated cervical vagi for 20 min and then removed. The success of PNCT was verified in each animal by the abolition of capsaicin (1 μg kg−1; i.v.)-induced reflex responses.

Study series 2

This series was carried out to investigate the effect of PAR2 activation on the sensitivity of isolated pulmonary chemosensitive neurons. Only the nodose/jugular ganglion neurons labelled with DiI as indicated by fluorescence intensity were investigated in this and the following study series. Capsaicin (0.3 or 1 μm, 2–6 s)-induced whole-cell inward current was determined before, and at different time points after pretreatment with trypsin (0.1 μm, 2 min) or the specific PAR2-activating peptide (PAR2-AP; 100 μm, 2 min). The effect of PAR2-AP on extracellular acidification (pH 6.0 or 5.5, 4–8 s)-induced inward current was also determined in a separate group of neurons.

Study series 3

This series was carried out to determine whether the effect of PAR2 activation was mediated through protein kinase C (PKC). The effects of pretreatment with U73122 (1 μm, 4 min), a phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor, and chelerythrine (10 μm, 4 min), a PKC inhibitor, on the sensitizing effect of PAR2-AP were investigated in two separate groups of pulmonary sensory neurons.

Solutions and chemicals

Standard extracellular solution (ECS) contained (mm): 136 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, 10 Hepes; pH 7.4. For acidic solutions with pH ≤ 6.0, Mes was used instead of Hepes for more reliable pH buffering. The intracellular solution contained (mm): 92 potassium gluconate, 40 KCl, 8 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes; pH at 7.2.

DiI was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA); PAR2-AP (SLIGRL-NH2) from Bachem (King of Prussia, PA, USA). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). Stock solutions of capsaicin (1 mm) were prepared in a vehicle of 10% Tween 80, 10% ethanol, and 80% ECS; those of trypsin (300 μm) and PAR2-AP (10 mm) were in ECS; and U73122 (3 mm) and chelerythrine (20 mm) were in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). These stock solutions were divided into small aliquots and kept at −80°C. The solutions of these chemicals at desired concentrations were prepared daily by dilution with saline and ECS for in vivo and patch-clamp studies, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When the ANOVA showed a significant interaction, pairwise comparisons were made with a post hoc analysis (Fisher's least significant difference). Results were considered significant when P < 0.05. Data are mean ±s.e.m.

Results

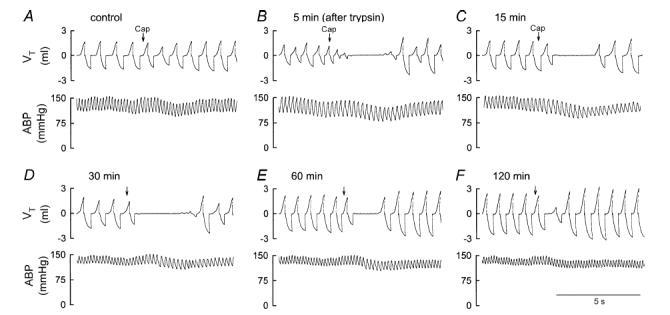

Pulmonary chemoreflex sensitivity is enhanced by airway exposure of trypsin

In anaesthetized, spontaneously breathing rats, right-atrial injection of a low dose of capsaicin (0.5 μg kg−1) elicited mild pulmonary chemoreflexes characterized by apnoea (or decrease in tidal volume), bradycardia and hypotension (e.g. Fig. 1A); injection of vehicle of capsaicin (saline) did not generate any apnoea, but caused only a slight and transient increase in ABP (data not shown). After intratracheal instillation of trypsin (0.8 mg ml−1, 0.1 ml), an activator of PAR2, the ventilatory and cardiovascular depressor responses to the same dose of capsaicin were greatly augmented and prolonged (Fig. 1). The potentiating effect of trypsin was long-lasting, reached a peak at ∼30 min, and gradually subsided after 120 min (Figs 1 and 2A). In contrast, as we reported previously (Lee et al. 2001), instillation of the same volume of isotonic saline, the vehicle of trypsin, had no detectable effect on the sensitivity of pulmonary chemoreflexes (n = 5).

Figure 1. Representative experimental records illustrating the potentiating effect of trypsin on the pulmonary chemoreflex responses to capsaicin in anaesthetized, spontaneously breathing rats.

A–F, responses to right atrial injection of capsaicin (0.5 μg kg−1) before, and 5, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min, respectively, after intratracheal instillation of trypsin (0.8 mg ml−1, 0.1 ml). Capsaicin (Cap; 0.1 ml) was first slowly injected into the catheter (dead space volume 0.2 ml) and then flushed (at arrow) as a bolus with saline (0.3 ml). VT, tidal volume; ABP, arterial blood pressure. Rat body weight, 415 g.

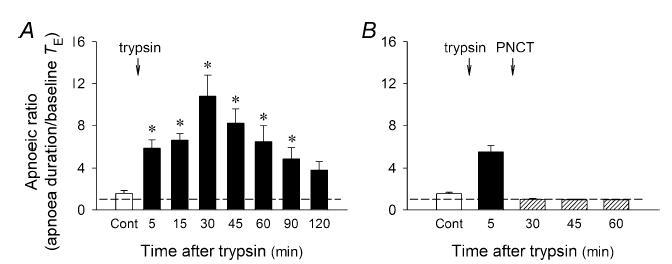

Figure 2. Group data illustrating the effect of trypsin on the apnoeic responses to capsaicin without (A) and with (B) perineural capsaicin treatment (PNCT) of both cervical vagi in anaesthetized, spontaneously breathing rats.

Apnoea duration, longest expiratory duration within 3 s after the injection of capsaicin (0.5–1 μg kg−1; i.v.). Baseline TE, average expiratory duration over 10 consecutive breaths immediately preceding the capsaicin injection. Open bars, control responses before intratracheal instillation of trypsin (0.8 mg ml−1, 0.1 ml). Filled bars, responses after the trypsin challenge. Hatched bars, responses after PNCT. Dashed line, apnoeic ratio of 100% level (no apnoea). Data represent mean ±s.e.m. (n = 8 and 4 in A and B, respectively). *P < 0.05 as compared with the corresponding control (Cont).

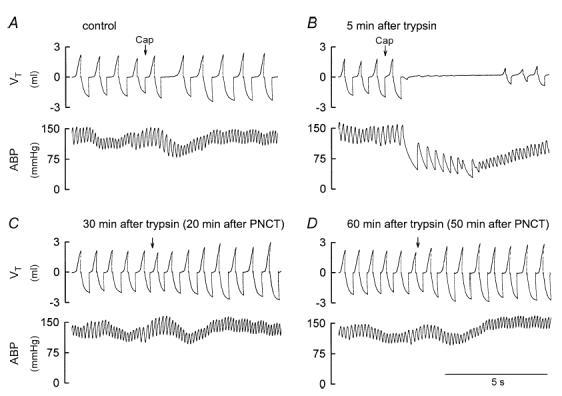

Perineural capsaicin treatment of both cervical vagi did not cause any significant change in baseline f, VT, ABP and heart rate. However, it completely blocked the trypsin-induced potentiation of the pulmonary chemoreflex responses to capsaicin (0.5–1 μg kg−1, i.v.; P > 0.05, n = 4) (Figs 2B and 3), indicating the involvement of vagal pulmonary C-fibres.

Figure 3. Experimental records illustrating that perineural capsaicin treatment (PNCT) of both cervical vagi abolished the potentiating effect of trypsin on the pulmonary chemoreflex responses to capsaicin in anaesthetized rats.

A, response to right atrial injection of capsaicin (Cap; 1 μg kg−1) at control. B, response to capsaicin 5 min after the intratracheal instillation of trypsin (0.8 mg ml−1, 0.1 ml). C, response to capsaicin 30 min after trypsin and 20 min after PNCT. D, response to capsaicin 60 min after trypsin and 50 min after PNCT. Rat body weight, 370 g.

Activation of PAR2 enhances the sensitivity of isolated rat vagal pulmonary chemosensitive neurons

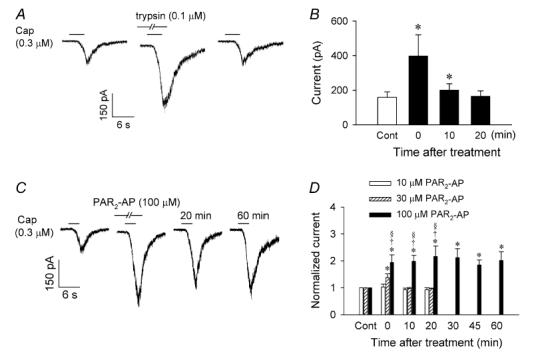

Application of capsaicin (0.3 or 1 μm, 1–6 s) evoked an inward current in small- to medium-sized (9.6–28.4 pF) pulmonary sensory neurons (e.g. Fig. 4A) which was mediated through the activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor type 1 (TRPV1) (Gu et al. 2005). Perfusion of trypsin (0.1 μm, 2 min) alone only induced a small inward current (30.4 ± 16.8 pA; n = 6) in six out of eight neurons tested (e.g. Fig. 4A), which developed slowly and progressively over a 2 min perfusion period of trypsin. However, pretreatment with trypsin significantly enhanced the response to the same concentration of capsaicin; the capsaicin-induced inward current was significantly potentiated from 158.7 ± 32.2 pA at control to 397.1 ± 123.3 pA (P < 0.05; n = 8) immediately after the trypsin pretreatment (Fig. 4B). The potentiated response to capsaicin returned to control when tested at 20 min (163.9 ± 32.2 pA) after the pretreatment.

Figure 4. Activation of PAR2 potentiated the capsaicin-evoked whole-cell inward current in isolated rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons.

A, experimental records illustrating that pretreatment with trypsin (0.1 μm, 2 min) potentiated the inward current evoked by capsaicin (Cap; 0.3 μm, 4 s). B, group data showing the effect of trypsin on capsaicin (0.3 or 1 μm, 4–6 s)-evoked current (n = 8). Data are mean ±s.e.m. *Significantly different from the control (Cont). C, experimental records illustrating the effect of pretreatment with PAR2-AP (100 μm, 2 min) on the capsaicin (0.3 μm, 3 s)-evoked inward current. D, group data showing the dose-dependent effect of PAR2-AP on the capsaicin (0.3 or 1 μm, 2–6 s)-evoked current; the responses are normalized with that evoked by the same concentration of capsaicin at control as 1.0. Data are mean ±s.e.m. (n = 6, 8 and 9 for 10 μm, 30 μm and 100 μm of PAR2-AP, respectively). *Significantly different from the corresponding control (Cont); †significantly different from 10 μm PAR2-AP at the same time point; §significantly different from 30 μm PAR2-AP at the same time point (P < 0.05).

The potentiating effect of trypsin on capsaicin-induced inward current was mimicked by PAR2-AP (Fig. 4C). The sensitizing effect of PAR2-AP was concentration dependent (Fig. 4D). Perfusion of 100 μm PAR2-AP (2 min) alone induced a small inward current (10.9 ± 5.2 pA; n = 16) in the majority (16/21) of the pulmonary sensory neurons tested (e.g. Fig. 4C), but it significantly potentiated the whole-cell inward current evoked by the same concentration of capsaicin (0.3 or 1 μm, 2–6 s); the capsaicin-induced current was significantly increased to 216% of its control level at 20 min after the PAR2-AP pretreatment (P < 0.05; n = 9). The potentiating effect of PAR2-AP lasted for more than 60 min in all nine neurons tested (Fig. 4D).

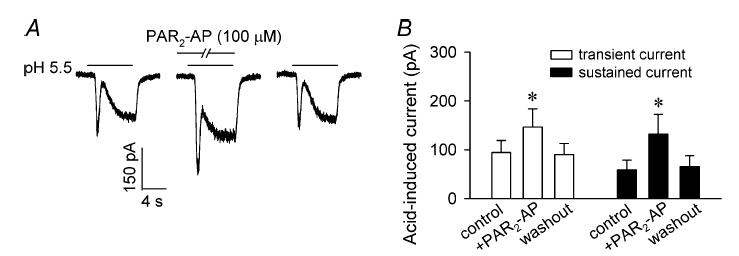

A separate series of experiments was carried out to determine whether the potentiating effect of PAR2 activation was limited to the response to capsaicin. As we have reported recently (Gu & Lee, 2006), application of physiologically/pathophysiologically relevant acidic solution to these sensory neurons evoked either a transient current mediated through acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) or a delayed and sustained inward current mediated through the activation of TRPV1, or both (e.g. Fig. 5A). Pretreatment with PAR2-AP (100 μm, 2 min) markedly potentiated the acid (pH 6.0–5.5, 4–8 s)-evoked inward currents; both the above-described current species were significantly enhanced, though the extent of potentiation was different: the ASIC-mediated transient current in response to acid application was potentiated from 94.5 ± 24.7 pA to 146.6 ± 37.2 pA, and the TRPV1-mediated sustained current was enhanced from 58.9 ± 19.7 pA to 132.1 ± 40.3 pA (Fig. 5B). Comparing this effect to that on capsaicin-evoked inward current, the potentiating effect of the same dose of PAR2-AP (100 μm, 2 min) on acid-evoked currents lasted for a much shorter time in these sensory neurons (< 20 min; Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Effect of PAR2-AP on acid-evoked inward currents in isolated rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons.

A, experimental records illustrating the effect of pretreatment of PAR2-AP (100 μm, 2 min) on the inward currents evoked by acidic solution (pH 5.5, 8 s); left: control; right: 20 min after washout. B, group data showing the effect of PAR2-AP on acid (pH 6.0–5.5, 4–8 s)-evoked currents. Data are mean ±s.e.m. (n = 12). *Significantly different from the corresponding control.

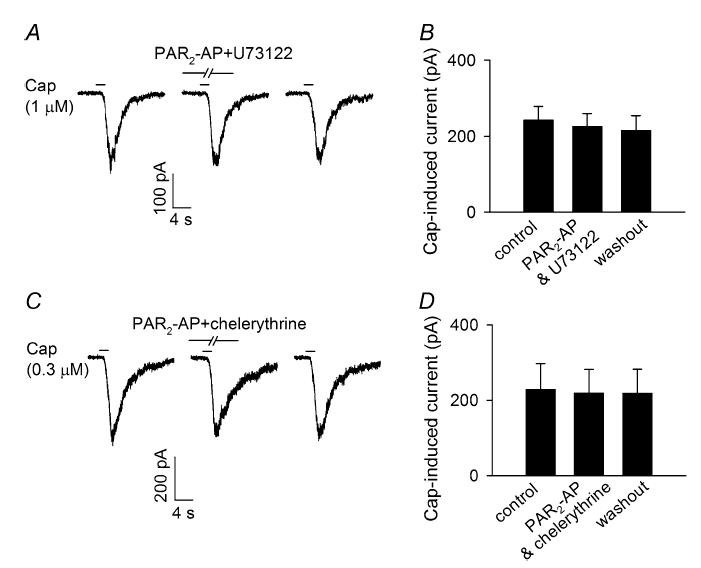

The sensitizing effect of PAR2 was mediated through the activation of PLC and PKC

In a number of different cell systems, PAR2 has been reported to be coupled to PKC activation via G-proteins (Gq/11) and the phosphatidylinositol pathway (Macfarlane et al. 2001; Amadesi et al. 2004; Dai et al. 2004). To determine a possible involvement of this transduction cascade in the pulmonary sensory neurons, we investigated whether U73122, an inhibitor of PLC, affected the sensitizing effect of PAR2-AP. As shown in Fig. 6A, pretreatment with U73122 (1 μm, 4 min) completely abolished the PAR2-AP (100 μm, 2 min)-induced potentiation of capsaicin (0.3 or 1 μm, 2–6 s) response in these neurons; the capsaicin-induced whole-cell inward current was 242.2 ± 36.4 pA at control and 225.1 ± 34.2 pA after pretreatment with both U73122 and PAR2-AP (P > 0.05, n = 6) (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Pretreatment with U73122, a phospholipase C inhibitor, or chelerythrine, a phosphate kinase C inhibitor, abolished the potentiating effect of PAR2-AP on capsaicin-induced current.

A, experimental records illustrating that the effect of PAR2-AP (100 μm, 2 min) on capsaicin (Cap; 1 μm, 2 s)-evoked current was abolished by pretreatment with U73122 (1 μm, 4 min); left, control; right, 20 min after washout. B, group data showing the effect of U73122 in six pulmonary sensory neurons. C, experimental records illustrating the effect of PAR2-AP (100 μm, 2 min) on capsaicin (0.3 μm, 2 s)-evoked current was completely blocked by pretreatment with chelerythrine (10 μm, 4 min); left, control; right, 20 min after washout. D, group data showing the effect of chelerythrine in eight pulmonary sensory neurons. Data are mean ±s.e.m.

Similarly, when pretreated with chelerythrine (10 μm, 4 min), a general PKC inhibitor, the potentiating effect of PAR2-AP (100 μm, 2 min) on capsaicin (0.3 or 1 μm, 2–6 s)-evoked inward current was also completely abolished (228.3 ± 68.8 pA at control; 218.5 ± 63.6 pA after pretreatment with chelerythrine and PAR2-AP; P > 0.05, n = 8) (Fig. 6C andD). Pretreatment with the vehicle of U73122 and chelerythrine (DMSO) did not affect the sensitizing effect of PAR2-AP on the capsaicin response in these neurons (data not shown).

Discussion

Our results have demonstrated that airway exposure of trypsin significantly amplified the capsaicin-induced pulmonary chemoreflex responses. The enhanced responses were completely abolished by PNCT of both cervical vagi, indicating the involvement of pulmonary C-fibre afferents. In isolated vagal pulmonary chemosensitive neurons, pretreatment with trypsin potentiated the capsaicin-induced whole-cell inward current. The potentiating effect of trypsin was mimicked by PAR2-AP in a concentration-dependent manner. PAR2-AP pretreatment also markedly enhanced the acid-evoked inward currents in these sensory neurons. In addition, the sensitizing effect of PAR2 was completely abolished by pretreatment with either U73122 or chelerythrine, suggesting that the effect of PAR2 activation was mediated through the PKC-dependent transduction pathway.

Recent studies have suggested that PAR2 is involved in airway inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness, which are prominent features of various chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (Cocks & Moffatt, 2001; Schmidlin et al. 2002; Barrios et al. 2003; Ebeling et al. 2005). Elevated levels of tryptase have been detected in the sputum (Louis et al. 2000) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (Wenzel et al. 1988) from asthmatic patients. PAR2-immunostaining has been shown to be significantly increased in epithelium from human asthmatics in comparison with that from normal subjects (Knight et al. 2001). Transgenic mice over-expressing PAR2 develop increasing levels of ovalbumin-mediated eosinophilic airway inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness compared with wild-type mice, whereas PAR2 knockout mice show the opposite effect (Schmidlin et al. 2002). In addition, activation of PAR2 has been shown to induce bronchoconstriction in guinea pigs in vivo (Ricciardolo et al. 2000), and contraction of isolated airways from both guinea pigs (Ricciardolo et al. 2000) and man in vitro (Chambers et al. 2001). Activation of PAR2 has also been shown to potentiate the histamine-induced contraction of isolated guinea-pig bronchi (Barrios et al. 2003), and sensitized (allergic) but not non-sensitized (non-allergic) human bronchus (Johnson et al. 1997; Chambers et al. 2001). More interestingly, the PAR2-induced bronchoconstriction and airway hyper-responsiveness described above are inhibited by the combination of neurokinin (NK)1, NK2 and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (Ricciardolo et al. 2000; Barrios et al. 2003), indicating the possible involvement of neuropeptides (such as tachykinins and CGRP) released from bronchopulmonary C-fibre afferents. Although the role of PAR2 in somatic inflammation and nociception has been recently reported in dorsal root ganglion neurons (Steinhoff et al. 2000; Vergnolle et al. 2001a; Amadesi et al. 2004; Dai et al. 2004), the effect of PAR2 on the bronchopulmonary C-fibre sensory neurons is not known.

Our results in this study have demonstrated that activation of PAR2 upregulates the pulmonary chemoreflex sensitivity in vivo (e.g. Figs 1 and 2) and the excitability of isolated pulmonary chemosensitive neurons in vitro (e.g. Figs 4 and 5). The importance of pulmonary C-fibres in the regulation of airway functions in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions is well recognized (Paintal, 1973; Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984; Lee & Pisarri, 2001; Lee & Undem, 2005). It is known that these C-fibre afferents can be stimulated by various endogenous substances (such as H+, anandamide and serotonin), inhaled irritants (e.g. cigarette smoke, acid aerosol, ozone, SO2, etc.) as well as lung expansion (e.g. increased tidal volume during exercise, sighing, etc.) (Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984; Carr & Undem, 2001; Lee & Undem, 2005). Activation of these afferents is known to evoke dyspnoeic sensation, airway irritation and cough, and to elicit reflex responses such as pulmonary chemoreflexes, bronchoconstriction and hypersecretion of mucus, which are mediated through the central nervous system and cholinergic pathway (Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984; Lee & Pisarri, 2001). In addition, tachykinins (substance P, neurokinin A, etc.) and CGRP released locally from these nerve endings upon activation can produce additional local effects such as airway constriction, protein extravasation, mucosal oedema and inflammatory cell chemotaxis (Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984; Solway & Leff, 1991; Lee & Undem, 2005). Thus, intense and/or sustained stimulation of these endings can lead to the development of ‘neurogenic inflammatory reaction’ in the airways (Barnes, 2001). Although the activators of PAR2 in the airways and lung structures are yet to be unequivocally identified, tryptase released from lung mast cells, trypsin-like proteases released from the airway epithelium and some house mite allergens, such as Der P1, Der P3 and Der P9, have been considered as possible candidates (Sun et al. 2001; Asokananthan et al. 2002; Schmidlin et al. 2002; Reed & Kita, 2004). It is reasonable to assume that when the PAR2 in the pulmonary C-fibres is activated by these endogenous or exogenous stimulants, the excitability of the C-fibre afferents will be elevated as demonstrated in the present study. Thus it will generate a more severe bronchoconstriction resulting from increases in both cholinergic reflex response and local tachykinin release, and contribute to the development of airway hyper-responsiveness.

Our results have shown that pretreatment with inhibitors of either PLC or PKC completely abolished the sensitizing effect of PAR2 activation in these vagal pulmonary chemosensitive neurons (Fig. 6). Indeed, in other cell systems such as somatic nociceptors (Amadesi et al. 2004; Dai et al. 2004), PAR2 is known to be coupled to Gq/11 protein and to activate PLC, resulting in generation of second messengers, inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol, which further triggers mobilization of Ca2+ and activation of PKC, respectively. PKC has been demonstrated to enhance the neuronal excitability by increasing the phosphorylation of certain ion channels such as the TRPV1 (Premkumar & Ahern, 2000; Vellani et al. 2001) and TTX-resistant Na+ channel (Rang & Ritchie, 1988; Khasar et al. 1999). In the present study, our results have also shown that the potentiating effect of PAR2 activation was not limited to the TRPV1-mediated capsaicin response; the acid-evoked inward currents in these sensory neurons were also significantly potentiated (Fig. 5). It has been recently demonstrated that physiologically/pathophysiologically relevant low pH stimulates the majority of the pulmonary sensory neurons through the activation of both ASICs and TRPV1 (Kollarik & Undem, 2002; Gu & Lee, 2006). However, the mechanism underlying the difference in the duration of the sensitizing effect of PAR2 activation between the responses to capsaicin (> 60 min; Fig. 4C and D) and acid (< 20 min; Fig. 5) in these neurons is not known.

It should be noted that although our study showed that activation of PAR2 can directly sensitize the pulmonary C-neurons, our results do not rule out the possibility that activation of PAR2 may also modulate the excitabilities of pulmonary C-fibre afferents indirectly. Indeed, it has been reported that the activation of PAR2 on epithelial cells is associated with release of various proinflammatory mediators including prostanoids such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (Cocks et al. 1999; Lan et al. 2001; Asokananthan et al. 2002), and cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 (Borger et al. 1999; Kauffman et al. 2000; Asokananthan et al. 2002). Some of these mediators such as PGE2 are known to possess potent sensitizing effects on these C-fibre afferents, elevating their sensitivities to various chemical and mechanical stimulations (Ho et al. 2000; Kwong & Lee, 2002; Gu et al. 2003).

In summary, our results show that activation of PAR2 upregulates the pulmonary chemoreflex sensitivity in vivo and the excitability of isolated pulmonary chemosensitive neurons in vitro. Our studies also demonstrate that the effect of PAR2 activation was mediated through the PLC/PKC transduction pathway. These results clearly illustrate the interactions between PAR2 and pulmonary sensory nerves, which may play a part in the airway hyper-responsiveness induced by PAR2 activation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michelle E. Wiggers and Robert F. Morton for their technical assistance. This study was supported by grants from NIH HL-58686 and HL-67379 (L.-Y. Lee), and the American Lung Association and Parker B. Francis Fellowship in Pulmonary Research (Q. Gu).

References

- Agostoni E, Chinnock JE, Daly M de B, Murray JG. Functional and histological studies of the vagus nerve and its branches to the heart, lungs and abdominal viscera in the cat. J Physiol. 1957;135:182–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers IA, Parsons M, Hill MR, Hollenberg MD, Sanjar S, Laurent GJ, McAnulty RJ. Mast cell tryptase stimulates human lung fibroblast proliferation via protease-activated receptor-2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L193–L201. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.1.L193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadesi S, Nie J, Vergnolle N, Cottrell GS, Grady EF, Trevisani M, Manni C, Geppetti P, McRoberts JA, Ennes H, Davis JB, Mayer EA, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptor 2 sensitizes the capsaicin receptor transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1 to induce hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4300–4312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5679-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asokananthan N, Graham PT, Stewart DJ, Bakker AJ, Eidne KA, Thompson PJ, Stewart GA. House dust mite allergens induce proinflammatory cytokines from respiratory epithelial cells: the cysteine protease allergen, Der p 1 activates protease-activated receptor (PAR)-2 and inactivates PAR-1. J Immunol. 2002;169:4572–4578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Neurogenic inflammation in the airways. Respir Physiol. 2001;125:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios VE, Jarosinski MA, Wright CD. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 mediates hyperresponsiveness in isolated guinea pig bronchi. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:519–525. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borger P, Koeter GH, Timmerman JA, Vellenga E, Tomee JF, Kauffman HF. Proteases from Aspergillus fumigatus induce interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 production in airway epithelial cell lines by transcriptional mechanisms. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1267–1274. doi: 10.1086/315027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr MJ, Undem BJ. Ion channels in airway afferent neurons. Respir Physiol. 2001;125:83–97. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers LS, Black JL, Poronnik P, Johnson PR. Functional effects of protease-activated receptor-2 stimulation on human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1369–L1378. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.6.L1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks TM, Fong B, Chow JM, Anderson GP, Frauman AG, Goldie RG, Henry PJ, Carr MJ, Hamilton JR, Moffatt JD. A protective role for protease-activated receptors in the airways. Nature. 1999;398:156–160. doi: 10.1038/18223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks TM, Moffatt JD. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) in the airways. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2001;14:183–191. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge JC, Coleridge HM. Afferent vagal C fibre innervation of the lungs and airways and its functional significance. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;99:1–110. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea MR, Derian CK, Leturcq D, Baker SM, Brunmark A, Ling P, Darrow AL, Santulli RJ, Brass LF, Andrade-Gordon P. Characterization of protease-activated receptor-2 immunoreactivity in normal human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:157–164. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Moriyama T, Higashi T, Togashi K, Kobayashi K, Yamanaka H, Tominaga M, Noguchi K. Proteinase-activated receptor 2-mediated potentiation of transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 activity reveals a mechanism for proteinase-induced inflammatory pain. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4293–4299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0454-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déry O, Corvera CU, Steinhoff M, Bunnett NW. Proteinase-activated receptors: novel mechanisms of signaling by serine proteases. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1429–C1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebeling C, Forsythe P, Ng J, Gordon JR, Hollenberg M, Vliagoftis H. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 activation in the airways enhances antigen-mediated airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness through different pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Kwong K, Lee LY. Calcium transient evoked by chemical stimulation is enhanced by PGE2 in rat vagal sensory neurons: role of cAMP/PKA transduction cascade. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1985–1993. doi: 10.1152/jn.00748.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Lee LY. Characterization of acid-signaling in rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L58–L65. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00517.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Lin RL, Hu HZ, Zhu MX, Lee LY. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate stimulates pulmonary C neurons via the activation of TRPV channels. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L932–L941. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00439.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CY, Gu Q, Hong JL, Lee LY. Prostaglandin E2 enhances chemical and mechanical sensitivities of pulmonary C fibers in the rat. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:528–533. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9910059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells GL, Macey MG, Chinni C, Hou L, Fox MT, Harriott P, Stone SR. Proteinase-activated receptor-2: expression by human neutrophils. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:881–887. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.7.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PR, Ammit AJ, Carlin SM, Armour CL, Caughey GH, Black JL. Mast cell tryptase potentiates histamine-induced contraction in human sensitized bronchus. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:38–43. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10010038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman HF, Tomee JF, van de Riet MA, Timmerman AJ, Borger P. Protease-dependent activation of epithelial cells by fungal allergens leads to morphologic changes and cytokine production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1185–1193. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasar SG, Lin YH, Martin A, Dadgar J, McMahon T, Wang D, Hundle B, Aley KO, Isenberg W, McCarter G, Green PG, Hodge CW, Levine JD, Messing RO. A novel nociceptor signaling pathway revealed in protein kinase C epsilon mutant mice. Neuron. 1999;24:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80837-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DA, Lim S, Scaffidi AK, Roche N, Chung KF, Stewart GA, Thompson PJ. Protease-activated receptors in human airways: upregulation of PAR-2 in respiratory epithelium from patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:797–803. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollarik M, Undem BJ. Mechanisms of acid-induced activation of airway afferent nerve fibres in guinea-pig. J Physiol. 2002;543:591–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong K, Lee LY. PGE2 sensitizes cultured pulmonary vagal sensory neurons to chemical and electrical stimuli. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1419–1428. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00382.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan RS, Knight DA, Stewart GA, Henry PJ. Role of PGE2 in protease-activated receptor-1 -2 and -4 mediated relaxation in the mouse isolated trachea. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:93–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Gu Q, Gleich GJ. Effects of human eosinophil granule-derived cationic proteins on C-fiber afferents in the rat lung. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1318–1326. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Pisarri TE. Afferent properties and reflex functions of bronchopulmonary C-fibers. Respir Physiol. 2001;125:47–65. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Undem BJ. Bronchopulmonary vagal afferent nerves. In: Undem BJ, Weinreich D, editors. Advances in Vagal Afferent Neurobiology. Frontiers in Neuroscience Series. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 279–313. [Google Scholar]

- Lin YS, Lee LY. Stimulation of pulmonary vagal C-fibres by anandamide in anaesthetized rats: role of vanilloid type 1 receptors. J Physiol. 2002;539:947–955. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis R, Lau LC, Bron AO, Roldaan AC, Radermecker M, Djukanovic R. The relationship between airways inflammation and asthma severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:9–16. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9802048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane SR, Seatter MJ, Kanke T, Hunter GD, Plevin R. Proteinase-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:245–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossovskaya VS, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptors: contribution to physiology and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:579–621. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paintal AS. Vagal sensory receptors and their reflex effects. Physiol Rev. 1973;53:159–227. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1973.53.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar LS, Ahern GP. Induction of vanilloid receptor channel activity by protein kinase C. Nature. 2000;408:985–990. doi: 10.1038/35050121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang HP, Ritchie JM. Depolarization of nonmyelinated fibers of the rat vagus nerve produced by activation of protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2606–2617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02606.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CE, Kita H. The role of protease activation of inflammation in allergic respiratory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardolo FL, Steinhoff M, Amadesi S, Guerrini R, Tognetto M, Trevisani M, Creminon C, Bertrand C, Bunnett NW, Fabbri LM, Salvadori S, Geppetti P. Presence and bronchomotor activity of protease-activated receptor-2 in guinea pig airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1672–1680. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9907133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidlin F, Amadesi S, Dabbagh K, Lewis DE, Knott P, Bunnett NW, Gater PR, Geppetti P, Bertrand C, Stevens ME. Protease-activated receptor 2 mediates eosinophil infiltration and hyperreactivity in allergic inflammation of the airway. J Immunol. 2002;169:5315–5321. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solway J, Leff AR. Sensory neuropeptides and airway function. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:2077–2087. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.6.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M, Vergnolle N, Young SH, Tognetto M, Amadesi S, Ennes HS, Trevisani M, Hollenberg MD, Wallace JL, Caughey GH, Mitchell SE, Williams LM, Geppetti P, Mayer EA, Bunnett NW. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism. Nat Med. 2000;6:151–158. doi: 10.1038/72247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Stacey MA, Schmidt M, Mori L, Mattoli S. Interaction of mite allergens Der p3 and Der p9 with protease-activated receptor-2 expressed by lung epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:1014–1021. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellani V, Mapplebeck S, Moriondo A, Davis JB, McNaughton PA. Protein kinase C activation potentiates gating of the vanilloid receptor VR1 by capsaicin, protons, heat and anandamide. J Physiol. 2001;534:813–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Bunnett NW, Sharkey KA, Brussee V, Compton SJ, Grady EF, Cirino G, Gerard N, Basbaum AI, Andrade-Gordon P, Hollenberg MD, Wallace JL. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 and hyperalgesia: a novel pain pathway. Nat Med. 2001a;7:821–826. doi: 10.1038/89945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Wallace JL, Bunnett NW, Hollenberg MD. Protease-activated receptors in inflammation, neuronal signaling and pain. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001b;22:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SE, Fowler AA, 3rd, Schwartz LB. Activation of pulmonary mast cells by bronchoalveolar allergen challenge. In vivo release of histamine and tryptase in atopic subjects with and without asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:1002–1008. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.5.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe JG. Nervous receptors in the respiratory tree and lungs. In: Hornbein TMD, editor. Lung Biology in Health and Disease. Regulation of Breathing. New York: Dekker; 1982. pp. 429–472. [Google Scholar]