Abstract

A model based on common trajectories of illness and associated care needs would improve the care of people with serious illness in the last phase of life, say Sydney Dy and Joanne Lynn

Most people believe their lives will be relatively healthy, punctuated by episodes of illness that last no more than a few weeks. On the rare occasions that we think about dying, we imagine short and overwhelming illness in old age. Healthcare systems are designed as if disability and ill health were aberrations, rather than a phase that lasts months or years near the end of our lives, despite the contrary evidence all around us. Because of improvements in sanitation, lifestyle, and medical care, only a small proportion of people in developed countries now die suddenly.1 Most serious chronic illnesses cannot be catered for adequately by traditional hospital and surgical services, and substantial restructuring is needed. The numbers of people living with serious chronic conditions in old age will double in the next two decades in the United States,2 and similar trends will be seen in many other countries.3 Finding sustainable ways to improve comfort and meaning in this last phase of life is therefore a priority.

Summary points

Patients coming to the end of life tend to follow one of three trajectories, with different priorities and needs

These trajectories are short decline, exacerbated organ system failure, and long term dementia or frailty

Small scale models of care based on these trajectories have helped improve patient centred outcomes

Larger scale initiatives to reform care systems are being evaluated in several countries

Although hospice programmes have been an important and instructive initial response, they do not meet the needs of most patients who are sick enough to die. A minority of people who die with chronic conditions use hospices, and then only for an average of a few weeks.4 In the US, enrolling in a hospice requires acknowledging a prognosis of “less than six months” and forgoing “curative” treatments.5 The inability of doctors to prognosticate with precision and the reticence of patients and doctors to accept these conditions restrict the use of hospice services. This has led to the conclusion, in the US6,7 and in the United Kingdom,8 that “end of life care” should encompass all people sick enough to die soon, even though some will live in fragile health for some years.

Many reforms redesign care for specific diseases or within specific settings. However, these approaches do not achieve continuity or comprehensiveness for the increasing numbers of patients with multiple chronic conditions who must use multiple settings of care, with their various methods of payment, and they rarely deal with end of life problems.9 Preferences for care at the end of life are likely to vary more than those for acute injury or illness, so reformers often emphasise allowing patients to choose their course of care.10 Patients' authority to refuse interventions is an important protection for dignity and autonomy, and the ability to shape the course of care is preferable to control by others. Yet, the greatest problem is that important services, such as home support and reliable transfers, often are not readily available or are unreliable. We have found it useful to identify the common patterns of care needs over time while living with fatal illnesses (often called “trajectories”) and to design services to fit them.

The trajectories

The clinical course of patients with eventually fatal chronic illness seems to follow three trajectories, described in more detail elsewhere.1,11,12 These trajectories provide a way to describe generalities about large and discernable groups of people, each with different time courses of illness, service needs, priorities for care, and current barriers to reliably high quality care.

The first trajectory is the maintenance of good function until a short period of relatively predictable decline in the last weeks or months of life. For these patients, planning ahead, aggressive management of symptoms at home, and the concerns of care givers often prevent unnecessary admissions to hospital and other disruptive, undesired, and potentially harmful interventions. This course is typical of common solid cancers in adults, although other diagnoses can have a similar course, and not all cancers fit into this category. Indeed, cancer is becoming a more chronic disease, often presenting as one more comorbidity among the chronic conditions of advanced old age (the third trajectory). About 20% of patients over 65 years in the US follow this trajectory, and they tend to die at a younger age than patients in the other trajectories.1

The second trajectory is chronic organ system failure, with slow decline punctuated by dramatic exacerbations that often end in sudden death. Chronic heart failure and emphysema are the prototypical illnesses, although any partially treatable serious chronic illness (such as renal failure or cirrhosis) may fall into this group. Optimal management may prevent exacerbations and some of the decline in function. Planning ahead for time limited trials of treatment, for the possibility of sudden dying, and for support of care givers and family increases the continuity and reliability of services. Such planning also makes it less likely that patients undergo unnecessary, burdensome, and costly treatments just before death. People living in this trajectory tend to be intermediate in age between the first and third patterns. Functional status is moderately but not severely limited, and cognitive failure is not prominent. About 25% of deaths in people over 65 in the US fit into this category.1

The third trajectory is poor long term functional status with slow decline. Very old patients with dementia, frailty, or multiple comorbidities (or a combination of these conditions) fit into this category. Younger patients with, for example, motor neurone disease, neurological complications of AIDS, and strokes can also follow this path. Because unpredictable minor illnesses, such as pneumonia, often cause decline or death, doctors frequently cannot predict survival. Patients usually require months or years of intensive care giving, problem solving, and supportive services, and intensive medical care often does not serve them well. Around 40% of people over 65 in the US follow this path.1

Of the 15% of deaths not readily classified into these three categories, about half appear to be sudden and the other half have patterns that have not yet been studied.1

Designing care to match trajectories

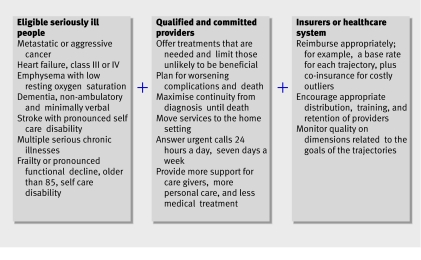

Some system elements are crucially important across all trajectories, including integrating care plans across settings, managing error-free transitions, problem solving, preventing complications and crises, ensuring comfort, planning ahead, and supporting loved ones in bereavement (figure).

The MediCaring model11

For other elements, patients have different priorities in different trajectories, so reform could build around typical patient situations in each trajectory (table 1). For the first trajectory, excellence requires integrating hospice or similar palliative care support with disease oriented treatment, and responding quickly to changes in symptoms. For the second trajectory, rapidly responsive disease management and mobilising services to the home can reduce exacerbations, prevent hospital admissions, and maximise the quality of the end of life. For the third trajectory, supportive services are crucial, and often need to endure for many years; interventional medical and surgical treatments are much less central to good care.

Table 1.

Elements of care important for patients coming to the end of life according to the 3 trajectories

| Care | Trajectory | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid decline over a few weeks or months before death | Chronic illness with intermittent exacerbations and sudden death | Very poor function, with long term slow decline | |

| Model of care | Well coordinated care; integration with hospice or palliative care when needed | Disease management with education and rapid intervention when needed | Long term supportive care |

| Specific care needs | Maximise continuity; plan for rapid decline, changing needs, and death; at-home management of patient's symptoms, acute needs of the care giver, and the dying process | Education on self care; prevention, early recognition, and management of exacerbations to avoid hospital admission when possible; maintenance of function; assistance with decision making about potentially low yield interventions; plan for potential sudden death | Plan for long term care and future problems; avoid non-beneficial and harmful interventions; support and assistance for long term care givers; reliable institutional care when necessary |

Table 2 shows an example of a successful reform project for each of the trajectories; recent systematic reviews9,13 describe others. Programmes for the frail elderly in other countries, such as Canada,17 and comprehensive programmes for cancer and chronic disease (see box) also show promise for transforming care. These programmes are mostly small and experimental, and they are not yet integrated into the healthcare or payment system. They are also available only to a fraction of patients who would benefit because of restrictive eligibility criteria or unsustained funding.

Table 2.

Examples of US programs oriented towards the 3 trajectories followed by patients at the end of life

| Programme | Trajectory | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid decline in function over a few weeks or months before death | Progressively compromised reserves with intermittent exacerbations and sudden death | Long term slow decline in function with frailty, dementia, or multiple chronic conditions | |

| Name | Project safe conduct14 | PhoenixCare15 | PACE (program of all-inclusive care for the elderly)16 |

| Design, year begun, patients served | Experimental, begun in 1998; continues to be offered for lung cancer patients at the cancer centre | Experimental, begun in 1998; now part of the Medicare coordinated care demonstration project for chronic conditions, in 15 sites with 14 000 patients | Experimental initially, begun in 1970; now a capitated Medicare benefit; currently, 35 programmes serve 17 000 patients throughout the US; continues to expand |

| Goals | To provide palliative care and life prolonging treatments | To reduce exacerbations and hospital admissions; to return control to patient and family; to allow patient and family to choose the site and situation of dying | To provide coordinated, community oriented supportive services, aimed at delaying or preventing placement in a nursing home |

| Population | Patients with advanced lung cancer | Patients with heart and lung failure with very limited reserve who have usually been admitted to hospital repeatedly | Age 55 or over; certified to need nursing home care; able to live safely in the community at time of enrolment |

| Intervention | Interdisciplinary palliative care and support from the time of diagnosis; family conferences and integration with cancer care | Optimal self management and home based case management incorporating palliative care and comprehensive advance care planning | Adult day care; coordinated medical care provided by PACE physician; capitated to include all other care |

| Evaluation | Evaluation before and after the intervention | Randomised trial | Observational study |

| Effects on the patient | Increased enrolment in hospices and longer length of stay | Improved functioning, self rated health, and symptoms; increased advanced care planning | High patient and family satisfaction; lower costs, less use of hospitals and nursing homes; higher numbers of deaths at home than the general elderly population |

Web links

Hastings Center. Improving end of life care: why has it been so difficult? www.thehastingscenter.org/research/healthcarepolicy8.asp

Lynn J, Schuster JL, Kabcenell A. Sourcebook: improving care for the end of life. www.medicaring.org

Examples of international quality improvement and system reorganisation

US: Promoting excellence in end-of-life care. www.promotingexcellence.org

UK: Gold standards framework. www.goldstandardsframework.nhs.uk/

Canada: Palliative care integration project. http://meds.queensu.ca/∼palcare/PCIP/PCIPHome.html

Sweden: The Esther project. See www.ihi.org

Australia: National palliative care program. www.health.gov.au/palliativecare

Two examples of incorporating these concepts into healthcare systems outside the US are the gold standards framework in the UK and the use of “Esther” paradigmatic patients in health planning in Sweden. The Esther project built care arrangements and prioritised reforms by testing service quality and reliability against prototypical patients, starting with a fictitious but typical complex and frail person that the team called Esther and expanding the concept to consider “Esthers” with colon cancer, with heart failure, and with dementia. This proved to be a useful construct for focusing on each of the populations needing services.

The gold standards framework incorporates end of life tools and resources into primary care practices, and it has already been adopted by more than 2000 primary care practices (covering a quarter of the UK population).8 This programme asks doctors to identify patients using the “surprise” question, “Would you be surprised if this patient died within the next year?” Patients identified in this way then have different measures of quality than those needing routine acute and preventive care services. Good advance care planning, symptom relief, home support, and other services become priorities and targets for quality improvement for those on the framework registry, whether the patient dies next week or lives with serious illness for a few months or years.

Customising and reorganising care to match the needs, rhythms, and situations of these three trajectories offers a promising way to improve outcomes for patients sick enough to die. If a community can build a care system that reliably serves the prototypical patient in each trajectory in their area, then almost everyone is guaranteed good care in the last phase of life. That insight simplifies what can seem an overwhelming array of details and possibilities. Such a framework would give direction to planners and managers to organise services, payments, and quality measures. It would also provide a basis for training healthcare workers and planning facilities for this population. It might also help advocacy groups that normally focus on disease specific issues to work together to identify and meet the common needs and priorities of care givers. If a region could deliberate on priorities, set goals, demand excellence, and monitor progress for each trajectory, civic and healthcare leaders and professionals might create a reliable care system for this fragmented and inefficient part of the healthcare picture.

Contributors and sources: SD is a hospice and palliative care physician and health services researcher and JL is a geriatrician, health services researcher, and coordinator of quality improvement initiatives for the last phase of life.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of older Medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1108-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans update 2006: key indicators of well-being. 2006. www.agingstats.gov/.

- 3.Office of National Statistics. National population projections. London: ONS, 2004. www.statistics.gov.uk/CCI/nugget.asp?ID=1352

- 4.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC). Medicare's hospice benefit: recent trends and consideration of payment system refinements. In: Report to the congress: increasing the value of Medicare. Washington, DC: MEDPAC, 2006:59-75. www.medpac.gov/publications/congressional_reports/Jun06_Ch03.pdf

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Coverage of hospice services under hospital insurance. In: Medicare benefit policy manual. Baltimore, MD: CMS, 2004. www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c09.pdf

- 6.National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: improving end-of-life care. December 6-8, 2004, Bethesda: Maryland, USA. J Palliat Med 2005;8(suppl):8 p preceding S1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Center to Advance Palliative Care, Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, Last Acts Partnership, National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, executive summary. J Palliat Med 2004;7:611-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King N, Thomas K, Martin N, Bell D, Farrell S. “Now nobody falls through the net”: practitioners' perspectives on the Gold Standards Framework for community palliative care. Palliat Med 2005;19:619-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorenz K, Lynn J, Morton SC, Dy S, Mularski R, Shugarman L, et al. End-of-life care and outcomes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tp/eoltp.htm

- 10.Hastings Center. Guidelines on the termination of life-sustaining treatment and care of the dying. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Hastings Center, 1987.

- 11.Lynn J. Sick to death and not going to take it any more. Reforming health care for the last years of life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004. www.medicaring.org/sicktodeath/index.html

- 12.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gysels M, Higginson IJ, Rajasekaran M, Davies E, Harding R. Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2003. www.nice.org.uk/110005

- 14.Ford PE, Beckham AM, Sivec HD. Project safe conduct integrates palliative goals into comprehensive cancer care. J Palliat Med 2003;6:645-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aiken LS, Kutner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med 2006;9:111-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temkin-Greener H, Mukamel DB. Predicting place of death in the program of all-inclusive care for the elderly (PACE): participant versus program characteristics. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:125-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kodner DL. Whole-system approaches to health and social care partnerships for the frail elderly: an exploration of North American models and lessons. Health Soc Care Community 2006;14:384-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]