Abstract

A rhodopsin-based homology model of the P2Y14 receptor was inserted into a phospholipid bilayer and refined by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. The binding modes of several known agonists, namely UDP-glucose and its analogues, were proposed using automatic molecular docking combined with Monte Carlo Multiple Minimum calculations. Compared to other P2Y receptors, the P2Y14 receptor has an atypical binding mode of the nucleobase, ribose and phosphate moieties. The diphosphate moiety interacts with only one cationic residue, namely Lys171 of EL2, while in other P2Y receptor subtypes three Arg or Lys residues interact with the phosphate chain. Two other conserved cationic residues, namely Arg253 (6.55) and Lys277 (7.35) of the P2Y14 receptor together with two anionic residues (Glu166 and Glu174 located in EL2), are likely involved in interactions with the distal hexose moiety.

Eight subtypes of P2Y receptors, namely P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14, have been cloned and characterized.1 All of these are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) belonging to the rhodopsin family. The P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, and P2Y11 are Gq-coupled receptors and comprise the P2Y1-like receptor family.2 A second family referred to as the P2Y12-like family consists of the P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14 receptors that couple via Gi proteins to the inhibition of adenylate cyclase.2 P2Y receptors are widely distributed throughout the body and are involved in many physiological processes.3 In particular, the P2Y14 receptor is likely involved in regulation of neuroimmune functions and is highly expressed in placenta, stomach, and intestine, and with moderate expression in brain, heart, lung, and spleen.4

In contrast to other P2Y receptor subtypes, the P2Y14 receptor is not activated by either nucleotide di- or triphosphates, such as ATP, UTP, or UDP, and dinucleotide.5–7

However, sugar-substituted analogues of UDP, namely UDP-glucose, UDP-galactose, and UDP-N-acetyl-glucosamine, are naturally occurring agonists of the P2Y14 receptor.4,8,9 Among these ligands, UDP-glucose is the most potent agonist.

Recently, molecular models of all known subtypes of P2Y receptors, including the P2Y14 receptor were published, and general configurations of the binding sites were proposed based on docking studies performed for the P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors.2 Several amino acid residues were suggested to be critical for ligand binding at both P2Y1-like and P2Y12-like receptor families of P2Y receptors.

Concerning the P2Y12-like family three cationic residues, namely Arg3.29, Lys located in EL2, and Lys7.36 were proposed to be critical for coordination of the phosphate chain of a ligand. Also, Ser7.43, present in the P2Y1-like family and in the P2Y12 receptor, seems to be involved in ligand binding via H-bonding with the nucleobase ring. This position is Ala7.43 in the P2Y13 and P2Y14 receptors. Tyr1.39, which was found to be involved in ligand recognition in the P2Y1 receptor, is conserved among all P2Y receptors, with the exception of the P2Y11 subtype. Tyr2.53 can interact with the native ligands at P2Y1, 2, 4, 6 subtypes, while in the P2Y12, 13, 14 receptors the corresponding residue is Met2.53. The P2Y12-like receptors, especially P2Y13 and P2Y14 receptors, likely have a different configuration of the binding site or different binding mode of its agonists in comparison to P2Y1-like receptors.2

In this study, a molecular model of the human P2Y14 receptor was refined by insertion into the phospholipid bilayer followed by 20 ns molecular dynamics simulation, and possible binding modes of four agonists of the P2Y14 receptor were studied using automatic docking followed by conformational search analysis.

Homology modeling is one of the most effective methods to study the structure and ligand-receptor interactions of GPCRs. The models obtained using this approach can provide information about residue – residue interactions, configuration of the putative ligand binding site, and possible binding modes of the ligands. However, such models have very similar configurations of the transmembrane domains (TMs) in comparison to the corresponding TMs of the template, usually rhodopsin. Homology modeling often cannot provide an accurate prediction of the configuration of the loops and terminal domains, especially if these sequences are quite long. Moreover, in most cases homology modeling does not take into account the natural environment of the membrane-bound GPCRs, although this is an important factor for the general configuration of a receptor structure and orientation of its sidechains.10

In this study, a previously published rhodopsin-based molecular model of the human P2Y14 receptor2 was refined using 20 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation in the phospholipid bilayer.

The MD simulation was performed using the protocol developed by Woolf and Roux11–14 and applied to MD simulation of the P2Y6 receptor by Costanzi et al.15 This simulation was run on the Biowulf cluster at the NIH (Bethesda, MD) using CHARMM 32a216 (details given in Supporting Information). As with the P2Y6 receptor,15 attempts to generate a MD trajectory without applying nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) restraints led to a loss of the secondary structure of TM7. For this reason the first 5 ns of the MD were performed with the NOE restraints applied for the distances between the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of the residue n and the backbone NH-group of the residue n+4 of TM7. That constraint preserved the helical structure of TM7, which remained stable after removing the NOE restraints.

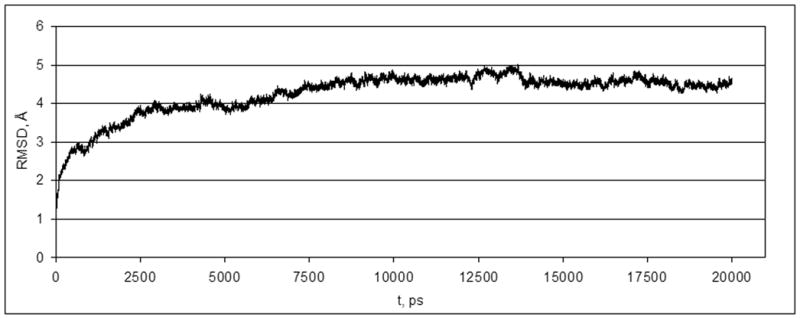

The root mean square deviation (RMSD) of all atoms of the P2Y14 receptor was calculated from the MD trajectory. As shown in Figure 1 the first plateau of the RMSD was reached after 2.5 ns of MD simulation.

Figure 1.

Changes in RMSD of atoms of the P2Y14 receptor during the MD simulation.

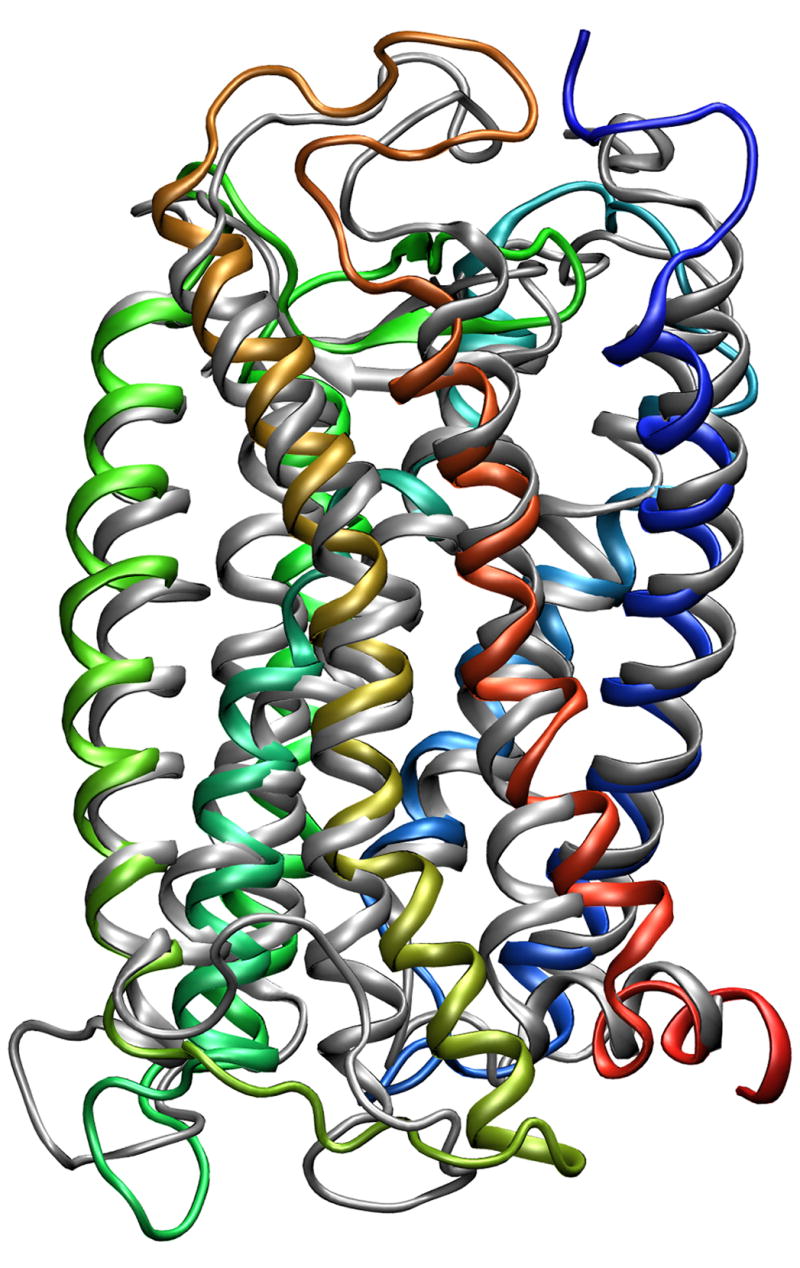

After 5 ns (when the NOE restrains were removed) the value of the RMSD was slightly increased, and after approximately 8.5 ns of MD simulation the structure of the receptor became stable. The typical structure of the last 100 ps of the trajectory was considered as a final structure of the MD simulation. The Cα-atoms of the transmembrane α-helices of this structure and an initial structure of the P2Y14 receptor were aligned with RMSD of 3.1 Å (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The alignment of the initial structure of the P2Y14 receptor (grey) and the structure obtained after MD simulation (colored). TMI – blue; TMII – light blue; TMIII – cyan; TMIV – lime green; TMV – green; TMVI – orange; TMVII – red.

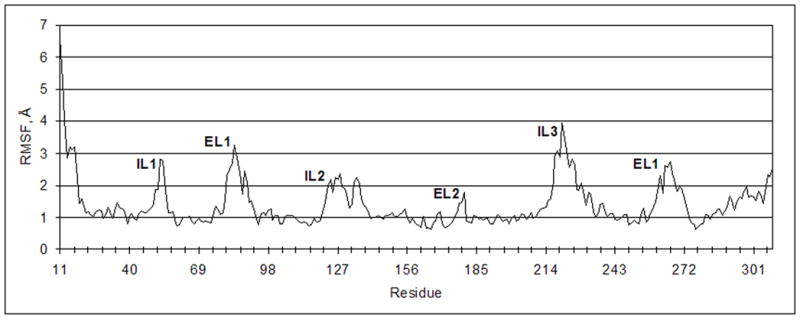

It was found that in general both structures have very similar configurations of the TMs. However, the angles along the axes of TM6 and TM7 changed slightly in comparison to the initial structure. The calculated values of the RMS fluctuations (RMSF) allowed us to indicate the residues with positions that were most significantly changed during the MD simulation. Not surprisingly, the highest values of the RMSF corresponded to the residues located in the extracellular (EL) and intracellular (IL) hydrophilic loops and terminal domains, while the residues located in the TM domain had the lowest values of the RMSF (Figure 3). In particular, the greatest change occurred in EL1 and IL3. In addition, during the simulation EL2 was shifted slightly outward from its initial position. However, the configuration of this longest hydrophilic loop was not significantly altered during the simulation.

Figure 3.

RMSF of the Cα-atoms of the P2Y14 receptor.

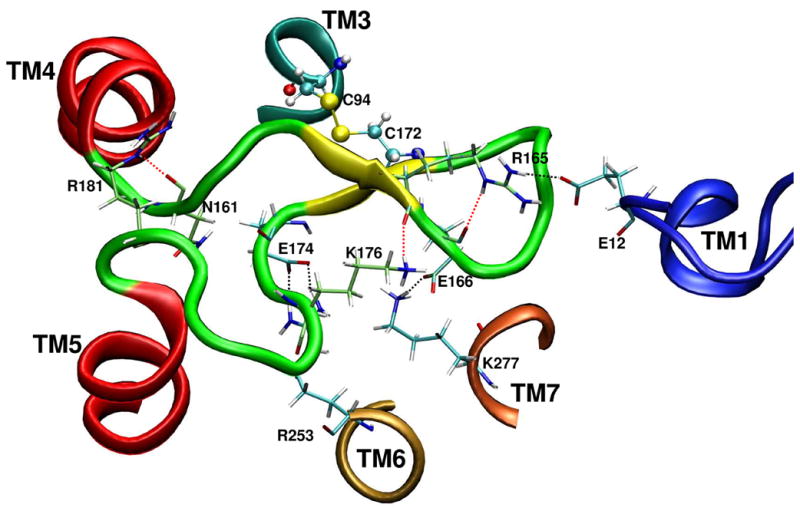

In addition to a conserved disulfide bridge and H bonds involved in formation of the β-sheet, several additional electrostatic bridges and H bonds were found to form among the residues located in EL2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The residue – residue bridges served to constrain the configuration of the EL2.

It was found that additional H bonds can be formed between Arg165(NH, sidechain) – Glu166(CO, backbone), Lys176(NH, sidechain) – Arg165(CO, backbone), Arg181(NH, sidechain) – Asn161(CO, backbone). Also, Arg253 (6.55) can interact with Glu174 (EL2), Lys277 (7.35) interacted with Glu166 (EL2), and Glu12 located in the N-terminal domain appeared near Arg165 (EL2). These findings suggest that in the case of the P2Y14 receptor, EL2 is a relatively rigid part of the receptor, and its conformation is constrained through a network of specific interactions.

The molecular model of the P2Y14 receptor obtained after MD simulation was used for a molecular docking study of UDP-glucose 1. During the first step, the ligand was docked automatically to the rigid putative binding site using the Autodock program17 (using parameters given in Supporting Information). This approach allowed the automatic location of the most favorable position and conformation of a flexible ligand, while avoiding radical changes in the receptor structure. The results of the automatic docking were analyzed, and the 3 ligand-receptor complex with the most favorable energy scoring function and most in agreement with available published data,2,15,18 was selected for further studies. To obtain a more accurate binding mode of UDP-glucose, the complex obtained after the automatic docking was used as a starting point for a Monte Carlo Multiple Minimum (MCMM) conformational search analysis of the ligand inside the putative binding site of the P2Y14 receptor. The MCMM calculations were performed using MacroModel software.19

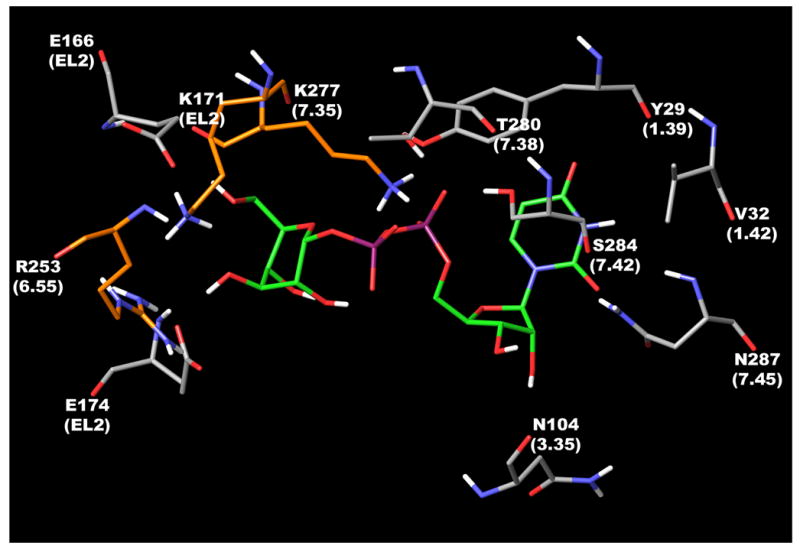

It should be noted that for four other subtypes of P2Y receptors the Northern (N) conformation of the ribose ring was proposed as the preferred conformation.20 In the present study conformers of 1 having both (N)- and (S)-conformations of the ribose ring were examined. The binding modes of (N)- and (S)-UDP-glucose obtained after MCMM calculations demonstrated that in both cases the ether oxygen and the 3′-hydroxyl group of the ribose ring were not involved in H-bonding with the receptor. In contrast, the 2′-hydroxyl group of (N)-UDP-glucose was H-bonded with the backbone oxygen atom of Asn104 (3.35) (Figure 5), while the 2′-hydroxyl group of (S)-UDP-glucose formed a H bond with the sidechain amino group of Asn287 (7.45) and the backbone oxygen atom of Ser284 (7.42).

Figure 5.

The binding mode of the UDP-glucose with the P2Y14 receptor obtained after MCMM calculations. Three key cationic residues, namely Lys171, Arg253, and Lys277 are colored in orange.

This means that in the case of (N)-UDP-glucose, the 2′-hydroxyl group could be a H bond donor, while in case of the (S)-conformation it is more likely to be both donor and acceptor.

The uracil ring of (N)- and (S)-UDP-glucose appeared near and oriented toward Tyr29 (1.39), which is a highly conserved residue among all P2Y receptors with the exception of Leu1.39 in the P2Y11 receptor. A similar orientation of the uracil ring was previously proposed for other subtypes of P2Y receptors.2,14,18 The carbonyl oxygen atom at position 4 of the uracil ring was located at a distance of 6.5Å from the Tyr29 hydroxyl group. The carbonyl oxygen atom at position 2 was found at a distance of 4.7Å from the Asn287 sidechain amino group, 6.0Å from its backbone NH-group, and 5.3Å from the backbone NH-group of Val288. The 3-NH group of 1 was oriented toward the sidechains of Val32 and Val288. However, the possible importance of these residues in ligand recognition is yet to be tested experimentally.

In the model, the α-phosphate group of 1 interacted with the hydroxyl groups of Thr280 (7.38) and Ser284 (7.42). Thr7.38 is conserved among all P2Y receptors with the exception of Met7.38 of the P2Y11 receptor. Position 7.42 is Ala7.42 in the P2Y1, 2, 4, 6 and P2Y13 receptors, Met7.42 in the P2Y11 receptor, and Thr7.42 in the P2Y12 receptor.

It was proposed previously2 that the ligand phosphate chain is located among three cationic residues, namely Arg3.29, Arg6.55, and Arg7.39 for P2Y1, 2, 4, 6, 11 receptors, and Lys from the EL2, Arg6.55, and Lys7.35 for P2Y12, 13, 14 receptors. The importance of these residues in P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors was demonstrated experimentally.2,21 The binding mode of 1 obtained in the present study demonstrated that in the case of the P2Y14 receptor only Lys171 located in EL2 can interact with the phosphate chain of 1. Arg6.55 and Lys7.35 appeared far from the phosphate groups and were located near the hexose moiety of the ligand. Moreover, the sidechain amino group of Lys7.35 was located between hydroxyl groups at the 5 and 3 positions of the glucose ring and formed H-bonds with both these groups. Also, the 3-hydroxyl group interacted with Glu166, while the 5-hydroxyl group seemed to be H-bonded with Glu174 located in EL2. Interestingly, Glu174 of the P2Y14 receptor corresponds to Asp204 of the P2Y1 receptor located in EL2 at a site two residues after the conserved Cys. It was demonstrated using molecular modeling22,23 that Asp204 of the P2Y1 receptor is located within 5Å from the triphosphate chain of ATP. Based on that model and mutagenesis data24 the involvement of Asp204 in ligand recognition through a water molecule bridge was proposed. An important role of the corresponding Asp was also suggested in molecular modeling studies performed for the P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors.15,18 Moreover, Glu767 of the human Ca2+ receptor25 and Tyr181 of the THR-receptor26 (both also located in EL2 at a site two residues after the conserved Cys) were shown to be crucial for receptor activation. In the model obtained, the ether oxygen atom and the 4- and 2-hydroxyl groups of the glucose moiety were not directly involved in H bonding with the receptor. As shown in Figure 5, the conformation of the hexose ring obtained automatically after the docking studies is different from the more stable alternate chair conformation of such rings. It could be proposed that the obtained conformation of the hexose moiety is stabilized inside the binding site by specific interactions with the receptor, namely by H-bonds with Arg253 (6.55), Lys277 (7.35), Glu166 (EL2), and Glu174 (EL2).

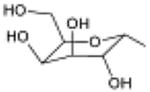

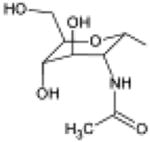

In order to explain experimentally observed differences in the activity of UDP-glucose 1, UDP-galactose 2, UDP-glucuronic acid 3, and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4 (Table 1), the three latter ligands were also subjected to MCMM calculations.

Table 1.

Agonist potencies at the human P2Y14 receptor. The experimental values of EC50 for stimulation of PLC (n = 6) were determined in COS-7 cells expressing the receptor (and an engineered G protein for coupling to PLCβ) were obtained as previously described.8

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Ligand | R | EC50, nM |

| 1, UDP-glucose |

|

354±115 |

| 2, UDP-glucuronic acid |

|

370±69 |

| 3, UDP-galactose |

|

671±90 |

| 4, UDP-N-acetyl-glucosamine |

|

4380±1050 |

For this purpose, the hexose ring of 1 was converted to a galactose or glucuronic acid moiety directly in the binding site. It allowed a ligand orientation inside the binding site similar to the orientation obtained for UDP-glucose. MCMM calculations were subsequently performed for 2 – 4 docked inside the P2Y14 receptor.

The general position of the ligands inside the binding site was unchanged during the MCMM calculations. All ligand-receptor interactions found for the UDP moiety of 1 were also observed for analogues 2 – 4. In the case of 3 one additional H-bond was found to form between Glu174 and the 4-hydroxyl group of the ligand, while in the case of 2 additional H-bonds between the hexose moiety and the receptor were not observed. However, the 4-hydroxyl group of 3 and a hexose carbonyl oxygen atom of 2 were unfavorably located in proximity to the hydrophobic sidechain of Ile173 located in EL2.

When the least potent agonist 4 was docked in the P2Y14 receptor, H-bonding was not observed between the receptor and the acetamide group of the ligand. In contrast, due to the short distance between the methyl groups of 4 and Met3.36, the sidechain of Met3.36 shifted away from the ligand. In addition, the methyl group of 4 was found close to the backbone oxygen atom of Phe3.32.

In conclusion, compared to other P2Y receptors, the P2Y14 receptor has an atypical binding mode of the nucleobase, ribose and phosphate moieties. The ligand binding modes obtained in this study demonstrated that two key cationic residues, namely Arg6.55 and Lys7.35, together with two anionic residues (Glu166 and Glu174 located in EL2), can interact with the hexose moiety. A third conserved key cationic residue, namely Lys171, interacts with the α-phosphate group of the ligand. The lower activity of 4 and its receptor docking suggest limited steric tolerance at the 2 position of the hexose moiety.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefano Costanzi (NIDDK) and Addison Ault (Princeton University) for helpful discussions. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Supporting information available: Calculation details including the MD simulation, automatic docking, and MCMM calculation parameters.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ford SM, Bonner TI, Neubig RR, Rosser EM, Pin JP, Davenport AP, Spedding M, Harmar AJ. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:279. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costanzi S, Mamedova L, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5393. doi: 10.1021/jm049914c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunschweiger A, Müller CE. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:289. doi: 10.2174/092986706775476052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbracchio MP, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Miras-Portugal MT, King BF, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA, Burnstock G. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:52. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)00038-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson KA, Costanzi S, Ohno M, Joshi BV, Besada P, Xu B, Tchilibon S. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:671. doi: 10.2174/1568026043450961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaver SR, Rideout JL, Pendergast W, Douglas JG, Brown EG, Boyer JL, Patel RI, Redick CC, Jones AC, Picher M, Yerxa BR. Purinergic Signaling. 2005;1:183. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-0648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers JK, Macdonald LE, Sarau HM, Ames RS, Freeman K, Foley JJ, Zhu Y, McLaughlin MM, Murdock P, McMillan L, Trill J, Swift A, Aiyar N, Taylor P, Vawter L, Naheed S, Szekeres P, Hervieu G, Scott C, Watson JM, Murphy AJ, Duzic E, Klein C, Bergsma DJ, Wilson S, Livi GP. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazarowski ER, Shea DA, Boucher RC, Harden TK. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1190. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ault AD, Broach JR. Protein Eng. 2006;19:1. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzi069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehler EL, Periole X, Hassan SA, Weinstein H. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2002;16:841. doi: 10.1023/a:1023845015343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woolf TB, Roux B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolf TB, Roux B. Proteins. 1996;24:92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199601)24:1<92::AID-PROT7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen TW, Andersen OS, Roux B. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9868. doi: 10.1021/ja029317k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. http://thallium.med.cornell.edu/RouxLab/

- 15.Costanzi S, Joshi BV, Maddileti S, Mamedova L, Gonzalez-Moa MJ, Marquez VE, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 2005;48:8108. doi: 10.1021/jm050911p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. J Comput Chem. 1983;4:187. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson KA, Costanzi S, Ivanov AA, Tchilibon S, Besada P, Gao ZG, Maddileti S, Harden TK. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:540. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohamadi FN, Richards GJ, Guida WC, Liskamp R, Lipton M, Caufield C, Chang G, Hendrickson T, Still WC. J Comput Chem. 1990;11:440. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim HS, Ravi RG, Marquez VE, Maddileti S, Wihlborg AK, Erlinge D, Malmsjö M, Boyer JL, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 2002;45:208. doi: 10.1021/jm010369e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erb L, Garrad R, Wang Y, Quinn T, Turner JT, Weisman GA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moro S, Hoffmann C, Jacobson KA. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3498. doi: 10.1021/bi982369v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Major DT, Fischer B. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4391. doi: 10.1021/jm049772m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann C, Moro S, Nicholas RA, Harden KA, Jacobson KA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray K, Ghosh SP, Northup JK. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3892. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perlman JH, Colson AO, Jain R, Czyzewski B, Cohen LA, Osman R, Gershengorn MC. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15670. doi: 10.1021/bi9713310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.