Abstract

DMT1 (divalent metal-ion transporter 1) is a widely expressed metal-ion transporter that is vital for intestinal iron absorption and iron utilization by most cell types throughout the body, including erythroid precursors. Mutations in DMT1 cause severe microcytic anaemia in animal models. Four DMT1 isoforms that differ in their N- and C-termini arise from mRNA transcripts that vary both at their 5′-ends (starting in exon 1A or exon 1B) and at their 3′-ends giving rise to mRNAs containing (+) or lacking (−) the 3′-IRE (iron-responsive element) and resulting in altered C-terminal coding sequences. To determine whether these variations result in functional differences between isoforms, we explored the functional properties of each isoform using the voltage clamp and radiotracer assays in cRNA-injected Xenopus oocytes. 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 mediated Fe2+-evoked currents that were saturable (K0.5Fe≈1–2 μM), temperature-dependent (Q10≈2), H+-dependent (K0.5H≈1 μM) and voltage-dependent. 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 exhibited the provisional substrate profile (ranked on currents) Cd2+, Co2+, Fe2+, Mn2+>Ni2+, V3+≫Pb2+. Zn2+ also evoked large currents; however, the zinc-evoked current was accounted for by H+ and Cl− conductances and was not associated with significant Zn2+ transport. 1B/IRE(+)-DMT1 exhibited the same substrate profile, Fe2+ affinity and dependence on the H+ electrochemical gradient. Each isoform mediated 55Fe2+ uptake and Fe2+-evoked currents at low extracellular pH. Whereas iron transport activity varied markedly between the four isoforms, the activity for each correlated with the density of anti-DMT1 immunostaining in the plasma membrane, and the turnover rate of the Fe2+ transport cycle did not differ between isoforms. Therefore all four isoforms of human DMT1 function as metal-ion transporters of equivalent efficiency. Our results reveal that the N- and C-terminal sequence variations among the DMT1 isoforms do not alter DMT1 functional properties. We therefore propose that these variations serve as tissue-specific signals or cues to direct DMT1 to the appropriate subcellular compartments (e.g. in erythroid cells) or the plasma membrane (e.g. in intestine).

Keywords: anaemia, divalent metal-ion transporter 1 (DMT1), iron absorption, natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein 2 (Nramp2), solute carrier family 11 member 2 (SLC11A2)

Abbreviations: αMeGlc, α-methyl D-glucopyranoside; DMT1, divalent metal-ion transporter 1; hDMT1, human DMT1; IRE, iron-responsive element; ORF, open reading frame; PIPPS, piperazine-1,4-bis-(2-propanesulfonic acid); rbSGLT1, rabbit sodium-dependent glucose transporter 1; RT, reverse transcriptase; SLC11A2, solute carrier family 11 member 2; UTR, untranslated region

INTRODUCTION

DMT1 [divalent metal-ion transporter 1; DCT1, Nramp2 (natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein 2) or SLC11A2 (solute carrier family 11 member 2)] is a widely expressed, mammalian ferrous-ion (Fe2+) transporter that is energized by the H+ electrochemical potential gradient [1]. Its vital role in iron homoeostasis [2] is highlighted by the impaired intestinal absorption and severe microcytic anaemia characteristic of the DMT1 knockout mouse [3], as well as the mk mouse and Belgrade (b) rat – inbred rodent strains that bear an identical (G185R) mutation in DMT1 (reviewed in [4]). DMT1 mediates apical iron uptake in the intestine and kidney, and recovery of iron from recycling endosomes during transferrin receptor-associated cellular uptake in erythroid precursor cells and in most other cell types (reviewed in [5,6]).

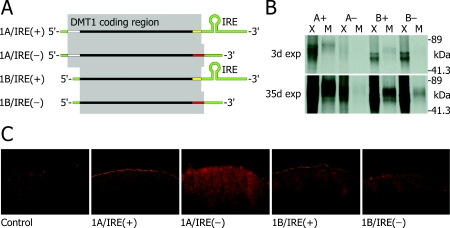

Transcription of the mammalian SLC11A2 genes coding for DMT1 gives rise to four variant mRNA transcripts (Figure 1A) that differ in their tissue distribution and regulation [2,7]. A 5′-end mRNA processing variant starts from exon 1A, which is located upstream of the first exon (‘1B’) of the previously characterized hDMT1 (human DMT1). The 1A exon (which contains a start codon) is followed by a consensus splice sequence and is spliced directly to exon 2. Meanwhile, exon 1B is not translated and translation begins with a start codon in exon 2. Whereas the 1B isoform is ubiquitous, the 1A isoform is tissue-specific, found predominantly in the duodenum and kidney [7]. In addition, variable 3′-end processing yields two transcripts that differ in their 3′-translated regions and UTRs (untranslated regions) [8,9]. One of the transcripts, denoted IRE(+), contains in its 3′-UTR an IRE (iron-responsive element) that may, in analogy with the transferrin receptor [10], alter mRNA stability according to iron status, so that the IRE-containing and non-IRE forms may be expected to differ mainly in their regulation by iron. Notably, both the 1A exon and the IRE(+) variant contributed to regulation by iron status in the duodenum and in Caco-2 cells [7].

Figure 1. Multiple isoforms of hDMT1.

(A) Variant transcripts of the human SLC11A2 gene. There are at least four DMT1 mRNA transcripts (illustrated) that differ in their UTRs (green) and in their coding regions [7]. The 1A exon contains a start codon upstream of that in 1B, adding a 5′-coding region (white) that introduces 29 additional amino acids at the N-terminus of the protein in 1A isoforms. DMT1 transcripts also vary at the 3′-end [8,9,18]: those variants containing an IRE in the 3′-UTR, i.e. IRE(+) isoforms, also have an isoform-specific 3′ coding region (yellow) in place of the 3′ coding region (red) in the isoforms lacking the IRE, i.e. IRE(−). The C-terminus of the IRE(+) forms contains 18 amino acid residues that substitute for the final 25 of the IRE(−) forms. (B) Coupled transcription–translation of the multiple isoforms of hDMT1 in a cell-free system, in the absence (X) or presence (M) of canine pancreatic microsomes. L-[35S]methionine-labelled products were separated by SDS/PAGE and the autoradiograph exposed for 3 days (3d exp, upper panel) or 35 days (35d exp, lower panel). A+, 1A/IRE(+)-hDMT1 isoform; A−, 1A/IRE(−); B+, 1B/IRE(+); B−, 1B/IRE(−). Molecular mass of translation products was estimated using Bio-Rad standards of 31.8, 41.3, 89, 131 and 210 kDa. (C) DMT1 immunofluorescence in control oocytes and oocytes expressing DMT1 isoforms.

Initiation from the 1A exon introduces 29 N-terminal amino acids not present in the 1B isoforms. Meanwhile, the C-terminus of the IRE(+) forms contains 18 amino acid residues that substitute for the final 25 of the non-IRE or ‘IRE(−)’ forms. The DMT1 N- and C-termini may contain signal sequences directing the subcellular targeting of each isoform and here we consider whether these sequence variations alter the functional properties of the four isoforms.

We describe here the expression and functional characterization of the four isoforms of hDMT1 using functional assays and immunocytochemistry in the Xenopus oocyte heterologous expression system and expression in a cell-free transcription–translation system. By studying the 1A/IRE(+) isoform in detail, we provide a thorough kinetic analysis of hDMT1 and examine its substrate profile. We also re-evaluate the roles of DMT1 in Zn2+, Ca2+ and Na+ transport. We compare the basic kinetic mechanisms and substrate profile of 1B/IRE(+) with those of 1A/IRE(+) to test whether N-terminal variations alter functional properties.

Part of this work was presented at ‘Experimental Biology 2004’ held in Washington, DC, U.S.A., on 17–21 April 2004 ([46]; 2004 Experimental Biology meeting abstracts, http://select.biosis.org/faseb/eb2004_data/FASEB005528.html).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of cDNA and cRNA for hDMT1 and rbSGLT1 (rabbit sodium-dependent glucose transporter 1)

hDMT1 is the product of the SLC11A2 gene [5]. The ORF (open reading frame) of 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 was obtained by RT (reverse transcriptase)–PCR amplification of total RNA isolated from Caco-2 cells treated with desferrioxamine as described previously [7] using the oligonucleotide primers GGAGCTGGCATTGGGAAAGTC and CCTAAGCCTGATAGAGCTAG, and inserted into pBluescript SK under the T3 promoter. 1B/IRE(+)-DMT1 [accession number NM_000617 in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) Entrez database] was isolated from a commercial human small-intestinal cDNA library in pCMV6-XL4 (Origene) and subcloned into pBluescript SK under the T3 promoter. The coding region corresponding to the IRE(−)-specific sequences was obtained by RT–PCR amplification of Caco-2 cell total RNA with the oligonucleotide primers CTCTGCTTGTTGCTGTCTTCCAAGATGTAGAG and CTCGAGGTTAACGGGACACCTGGCACAAAAAGG and isolating a PstI–HpaI fragment from the amplicon. We inserted this fragment into both the 1A/IRE(+) and 1B/IRE(+) constructs that had been digested with PstI and EcoRV, thereby constructing plasmid cDNAs containing the ORFs of the 1A/IRE(−) and 1B/IRE(−) isoforms of DMT1. To maximize expression in Xenopus oocytes, we PCR-amplified the cDNA for each of the DMT1 isoforms from pBSK(−) and inserted these into the polylinker of the pOX(+) Xenopus oocyte expression vector [11] between KpnI and XhoI, under the SP6 promoter. DMT1-pOX(+) plasmids were linearized with SnaBI or HpaI. rbSGLT1 (the product of the Slc5a1 gene) [12,13] in pBluescript under the T3 promoter was linearized with NotI. cRNAs were synthesized in vitro with the use of the Ambion mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit along with SP6 RNA polymerase (for DMT1) and T3 RNA polymerase (for rbSGLT1) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Transcription and translation in vivo

We used a cell-free, coupled transcription–translation kit (Promega TNT SP6 Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System) in the presence or absence of canine pancreatic microsomal membranes (Promega), according to the manufacturer's protocols. We used 0.5 μg of each DMT1 cDNA in pOX(+) along with L-[35S]methionine (Amersham Biosciences). For those reactions containing microsomal membranes, we obtained the membrane fraction as described in [14] by adding 2.4 vol. of microsome-spinning buffer [3.5% (v/v) glycerol and 10 mM Tris base, pH 7.5] and then centrifuging at 13600 g for 30 min. The translation products were separated on a 0.1% SDS/10% polyacrylamide gel, alongside molecular mass standards (Bio-Rad). The gel was then fixed in 50% (v/v) methanol/10% (v/v) acetic acid for 2 h, washed in distilled water for 1 h, and incubated 2 h in Autofluor autoradiographic image enhancer (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A.) before it was dried. We exposed a Kodak BioMax film to the dried gel for 3 or 35 days at −80 °C. We predicted the molecular mass of each nascent peptide using the Compute pI/Mw tool [15] on the ExPASy server (http://au.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html). We predicted consensus sites (N-X-T/S sequons) for N-linked glycosylation using the NetNGlyc algorithm [16] (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/).

Expression of hDMT1 or rSGLT1 in Xenopus oocytes

We performed laparotomy and ovariectomy on adult female Xenopus laevis frogs under 2-aminoethylbenzoate anaesthesia (0.1% in 1:1 water/ice, by immersion) in compliance with the Harvard Area Standing Committee on Animals or the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Ovarian tissue was isolated and treated with collagenase A (Roche Diagnostics), and oocytes were isolated and stored at 18 °C in modified Barths' medium [17]. Oocytes were injected with approx. 50 ng of hDMT1 cRNA and incubated 3–5 days before performing voltage-clamp or radiotracer experiments, or preparing oocytes for immunocytochemistry. We also injected some oocytes with approx. 50 ng of rbSGLT1 cRNA and incubated these for 2 days before performing radiotracer experiments.

Immunocytochemistry

To verify the subcellular or plasma-membrane localization of DMT1 isoforms, cRNA-injected oocytes were embedded and freshly frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. (optimum cutting temperature) compound (Sakura Finetek U.S.A., Inc., Torrance, CA, U.S.A.) at day 5 post-injection. Immunocytochemistry was performed by UB-InSitu (Natick, MA, U.S.A.). Oocytes were cryostat-sectioned at 8 μm thickness and fixed in ethanol. We used an anti-DMT1 that was raised in rabbits against a synthetic peptide KPSQSQVLRGMFVPSC corresponding to the amino acid residues 230–245 of mouse DMT1 (SwissProt accession no. P49282) and affinity-purified as described previously [18]. We used the anti-DMT1 antibody 1:100 overnight, with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% normal goat serum, and secondary antibody, CY3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) for 2 h at 1:200 with 1% normal goat serum.

Voltage-clamp experiments and radiotracer transport assays

We used the voltage-clamp and radiotracer assays to examine the functional properties of multiple isoforms of DMT1 expressed in oocytes. Experiments were performed at room temperature (22–23 °C), except where noted. Oocytes were superfused or incubated with low-calcium transport media buffered using Mes buffer and PIPPS [piperazine-1,4-bis-(2-propanesulfonic acid; GFS Chemicals]. We used PIPPS, a non-complexing buffer with pKa2m≈8.0 [19], in place of the commonly used buffers Hepes and Tris in studies of metal-ion transport, since Hepes and Tris can complex metal ions [19,20]. In a previous study [21] of rat DMT1, we observed significantly reduced 55Fe2+ uptakes in media containing Hepes and Tris, presumably due to complexation. Transport media comprised 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 0.6 mM CaCl2 (except where noted), 1 mM MgCl2, 0–5 mM Mes buffer, 0–5 mM PIPPS and 0–6 mM NaOH. For low-Na+ media (for 22Na+ uptake experiments, see Figure 5B), 90% of the NaCl in our media (pH 7.5 or 5.5) was replaced by equimolar choline chloride. For all experiments involving Fe2+ and for other metal ions where indicated, media also contained 100 μM L-ascorbic acid (or 1 mM L-ascorbic acid for radiotracer experiments).

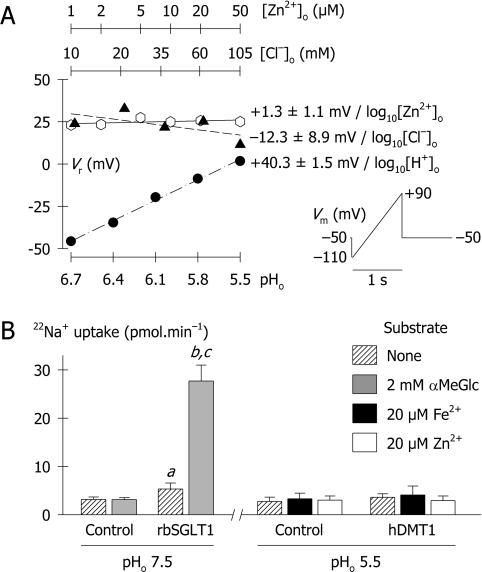

Figure 5. Ionic basis of the anomalous zinc-evoked currents.

(A) Reversal potential (Vr) as a function of [Zn2+]o, [Cl−]o or pHo. Voltage ramps [protocol (iv) in the Materials and methods section, and illustrated in the inset] were used to obtain Vr in 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1-expressing oocytes that had been chloride-dialysed for 12 h. Default conditions were: [Zn2+]o=50 μM; [Cl−]o=105.2 mM; pHo=5.5; [Na+]o=100 mM; and [Ca2+]o=0.6 mM. All solutions contained 100 μM niflumic acid and 0.1% DMSO. Vr varied with [Cl−]o by −12.3±8.9/log10[Cl−]o (empty hexagons, dashed line, r2=0.397), with pHo by +40.3±1.5 mV/log10[H+]o (filled circles, dotted-dashed line, r2=0.996), and with [Zn2+]o by 1.3±1.0 mV/log10[Zn2+]o (filled triangles, solid line, r2=0.256). (B) Uptake of 10 mM 22Na+ in control oocytes, and oocytes expressing either the rabbit Na+/glucose co-transporter SGLT1 (rbSGLT1) or 1A/IRE(+)-hDMT1. rbSGLT1-mediated 22Na+ uptake was assayed at pH 7.5 in the presence or absence of 2 mM αMeGlc (α-methyl D-glucopyranoside; a glucose analogue that is relatively specific for SGLT1). For hDMT1, 22Na+ uptake was measured at pH 5.5 in the absence of metal ion, or in the presence of 20 μM Fe2+ or Zn2+. Uptake was determined over 20 min; data are means±S.D. for 10–15 oocytes in each group. For rbSGLT1: a, P=0.005, compared with Control; b, P<0.001 compared with Control; c, P<0.001 αMeGlc versus no substrate. Two-way ANOVA revealed no statistical differences between any data groups for control and hDMT1 (P≥0.054).

We used the two-microelectrode voltage clamp (Dagan CA-1B amplifier) to measure currents in control oocytes and oocytes injected with hDMT1 cRNA. Microelectrodes (resistance 0.5–5 MΩ) were filled with 3 M KCl. Voltage-clamp experiments comprised four protocols: (i) continuous current recordings were made at a holding potential (Vh) of −70 mV, digitized at 10 Hz and low-pass filtered at 1 Hz. (ii) Oocytes were clamped at Vh=−50 mV, and step-changes in membrane potential (Vm) were applied from +50 to −150 mV (in 20 mV increments) each for a duration of 200 ms, before and after the addition of metal-ion substrate. Current was low-pass filtered at 500 Hz and digitized at 5 kHz. Steady-state data were obtained by averaging the points over the final 16.7 ms at each Vm step. (iii) Pre-steady-state currents were determined using protocol (ii) modified such that step-changes were applied from +90 to −110 mV. (iv) Oocytes were clamped at Vh=−50 mV and stepped to −110 mV for 20 ms (to allow for settling of the capacitive transient currents) before a 1 s ramp was applied from −110 to +90 mV (see inset to Figure 5A). Current was low-pass filtered at 500 Hz and digitized at 5 kHz. Currents obtained by protocol (iv) were used to determine reversal potential (Vr) under variable ionic conditions; the Vr/log10 [ion]out relationships were fitted by linear regression.

Steady-state data from protocols (i) or (ii) were fitted using a modified Hill function (eqn 1) for which I is the evoked current, Imax the derived current maximum, S the concentration of substrate S (H+ or metal ion), K0.5S the substrate concentration at which current was half-maximal, and nH the Hill coefficient for S. We have previously shown that the rat DMT1 can mediate facilitative Fe2+ transport at neutral pH, uncoupled from H+ [21]. With increasing [H+], this H+-uncoupled mode is inhibited in favour of H+/Fe2+ co-transport. The H+ concentration dependence of the Fe2+-evoked currents was therefore explored by alternatively fitting data using eqn (2), which comprises the Hill function and a term (iU) describing facilitative (H+-uncoupled) Fe2+ transport. IU is described empirically as decaying exponentially with increasing [H+].

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Following step-changes in Vm using protocol (iii), we obtained pre-steady-state currents in oocytes expressing human or rat DMT1. These were isolated from capacitive transient currents (which decayed with half times of 0.2–0.9 ms) and steady-state currents by the fitted method [17,21,22]. The compensated currents thus obtained were integrated with time to obtain charge movement (Q) and fitted by a Boltzmann function (eqn 3) for which maximal charge Qmax=Qdep−Qhyp (where Qdep and Qhyp represent the charge at depolarizing and hyperpolarizing limits), V0.5 is the Vm at the midpoint of charge transfer, z is the apparent valence of the movable charge, and F, R and T have their usual thermodynamic meanings.

|

(3) |

Transporter-mediated pre-steady-state currents can be used to estimate transporter density [23]. We estimated the number (per oocyte) of functional units (NT) of the DMT1 transporter expressed in the plasma membrane using eqn (4), in which e is the elementary charge (1.6×10−19 C).

|

(4) |

Currents obtained over the range of temperatures 18–31 °C (see Figure 4H) were fitted by an integrated Arrhenius function (eqn 5), for which Ea is the Arrhenius activation energy, A the y-intercept, R the universal gas constant (1.987 cal·mol−1·K−1; 1 cal≈4.184 J), T the absolute temperature, and I the current induced by switching from pH 7.5 to 5.5 (IΔpH, i.e. H+ leak) or the 20 μM Fe2+-evoked current at pH 5.5 (IFe, i.e. H+/Fe2+ co-transport).

|

(5) |

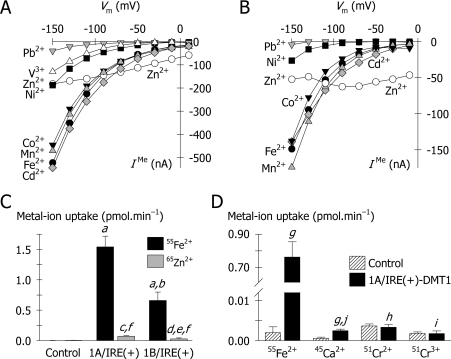

Figure 4. Substrate profile of hDMT1.

(A, B) Comparison of metal-ion-evoked currents for the 1A and 1B isoforms. Currents evoked by a range of metal ions (at 20 μM in pH 5.5 medium) were determined for the 1A/IRE(+) (in A) and 1B/IRE(+) (in B) isoforms of hDMT1 in the presence of 100 μM L-ascorbic acid, with the exception of V3+ currents, which were measured in the absence of L-ascorbic acid. Key to symbols: black circles, Fe2+; grey diamonds, Cd2+; grey triangles, Mn2+; black inverted triangles, Co2+; black squares, Ni2+; white triangles, V3+ [1A/IRE(+) only]; grey inverted triangles, Pb2+; white circles, Zn2+. (C) Uptake of 2 μM 55Fe2+ and 65Zn2+ uptake at pH 5.5 was measured in control oocytes, and oocytes expressing human 1A/IRE(+) or 1B/IRE(+) DMT1 isoforms. Data are means±S.D. from 6–14 oocytes. a, P<0.001 compared with Control; b, P<0.001 compared with 1A/IRE(+); c, not significant (P=0.160) compared with Control; d, not significant (P=0.683) compared with Control; e, not significant (P=0.347) compared with 1A/IRE(+); f, P<0.001 compared with 55Fe2+. (D) Calcium and chromium uptake in oocytes expressing DMT1. Uptake of 2 μM 55Fe2+, 45Ca2+ or 51Cr2+ was measured over 10 min at pH 5.5 in control oocytes and oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-hDMT1 in the presence of 1 mM L-ascorbic acid. Uptake of 2 μM 51Cr3+ was measured by excluding ascorbic acid from the medium. Data are means±S.D. for 8–25 oocytes in each group. 1A/IRE(+) compared with Control for each metal ion: g, P<0.001, h, not significant (P=0.214), and i, not significant (P=0.665). j, P<0.001 compared with 55Fe2+.

We obtained radiochemicals from PerkinElmer Life Science Products. In radiotracer transport assays, 55Fe was used at specific activity 658 MBq/mg, 65Zn at 110 MBq/mg, 51Cr at 29.5 MBq/mg, 22Na at 0.34 MBq/mg, and 45Ca at 436 MBq/mg. The time course of 2 μM 55Fe2+ uptake was determined between 2 min and 2 h. In subsequent experiments, radiotracer metal-ion uptake was measured over 10 min with up to 15 oocytes per 2 ml of transport medium. 22Na+ uptake was measured over 20 min. At the end of the uptake period, oocytes were rinsed twice with ice-cold pH 5.5 medium containing 500 μM unlabelled Fe2+ and 1 mM L-ascorbic acid and then solubilized with 5% (w/v) SDS. 55Fe, 65Zn, 22Na, or 45Ca content was assayed by liquid-scintillation counting using Fisher Scintisafe 30% liquid-scintillation cocktail, and 51Cr content was assayed by γ-radiation counting.

Statistical and regression analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat version 3.1 (Systat Software) with critical significance level α=0.05. Radiotracer uptake data (except data in Figure 2A) were analysed using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by pairwise multiple comparisons by the Holm–Sidak test, or using Dunn's test on ranks. Data for the time course of 55Fe2+ uptake (Figure 2A) and, where appropriate, voltage-clamp data were fitted by the least-squares method of linear or non-linear regression using SigmaStat and, in certain cases, followed by F-tests of the significance of the fit to the model (eqns 1, 2, 5 and 6). Pre-steady-state current data (Figure 2F and Table 1) were fitted by eqn (3) using Clampfit version 9.2 in the pCLAMP software suite (Axon Instruments).

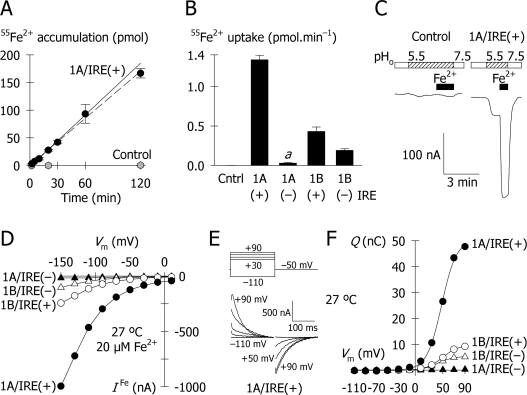

Figure 2. Functional activity of the multiple isoforms of hDMT1.

(A) Time course of 2 μM 55Fe2+ uptake (pH 5.5) in oocytes expressing the 1A/IRE(+) isoform of hDMT1 (black circles) and in control oocytes (grey hexagons). Results are means±S.D. for 9–13 oocytes in each group at each time point. The solid line shows the regression (r2=0.996, P<0.001) of data points for DMT1 from 2 min up to 1 h, but excludes that at 2 h. The dashed line shows the regression (r2=0.996, P<0.001) of all data points for DMT1 from 2 min to 2 h. (B) Uptake of 2 μM 55Fe2+ uptake (pH 5.5, 10 min) in control oocytes and oocyte expressing each of the DMT1 isoforms. Results are means±S.D. for 9–13 oocytes in each group; a, P=0.049 compared with Control, and all other pairwise comparisons, P≤10−13. (C) Typical current records for a control oocyte and an oocyte expressing 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 at −70 mV. Oocytes were superfused at pHo 7.5 for periods shown by the blank boxes, then at pHo 5.5 (hatched boxes). Fe2+ (20 μM) was superfused for the periods shown by the black boxes. (D) Current–voltage relationships (20 μM Fe2+, pHo 5.5, 27 °C) for the multiple isoforms of hDMT1: 1A/IRE(+) (filled circles), 1A/IRE(−) (filled triangles), 1B/IRE(+) (empty circles), and 1B/IRE(−) (empty triangles). (E, F) Pre-steady-state currents associated with hDMT1 at 27 °C. (E) Compensated records (see the Materials and methods section) for the 1A/IRE(+) isoform of hDMT1 shown from 9 ms after step-changes in membrane potential from −110 to +90 mV (upper panel). For clarity, only the records at −110, +30, +50, +70 and +90 mV are illustrated (omitting records at −90, −70, −50, −30, −10 and +10 mV). (F) Pre-steady-state currents for each isoform at pHo 5.5 were integrated with time to obtain charge, Q (using the same symbols as in D). The Q/Vm relationships were fitted by single Boltzmann functions (eqn 3) and the derived parameters are given in Table 1. Data in (F) are derived from the same four oocytes as in (D), all at 27 °C.

Table 1. Steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic parameters for the multiple isoforms of human DMT1.

The maximal current evoked by 20 μM Fe2+ (Figure 2D) was taken as Imax. Pre-steady-state parameters (Qmax, z and V0.5) are derived from data in Figures 2(E) and 2(F) fitted by eqn (3) (errors given are the standard error of the regression; r 2 is the regression coefficient). The number of functional transporter units (NT) expressed in the plasma membrane per oocyte is given by eqn (4). n.d., not determined. Turnover rate was determined as −Imax/Qmax. Half-maximal Fe2+ concentrations (K0.5Fe) are from data in Figure 3(A) fitted by eqn (1). Half-maximal H+ concentrations (K0.5H) are from data in Figures 3(E) and 3(F) fitted by eqn (2).

| Isoform | Imax (nA) | Qmax (nC) | Apparent valence (z) | V0.5 (mV) | r2 | 10−11×Transporter density (NT) (number/oocyte) | Turnover rate (s−1) | K0.5Fe (μM) | K0.5H (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A/IRE(+) | −995 | 50.2±0.8 | −1.9±0.1 | +47.9±0.7 | 0.976 | 1.6 | 20±1 | 1.5±0.1 | 1.3±0.5 |

| 1A/IRE(−) | −17 | ≈0.8 | n.d.. | n.d. | − | ≈0.03 (est.)* | ∼21 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 1B/IRE(+) | −244 | 9.9±0.2 | −1.7±0.1 | +49.4±0.9 | 0.977 | 0.4 | 25±1 | 1.0±0.2 | 1.6±0.3 |

| 1B/IRE(−) | −104 | 5.5±0.1 | −1.8±0.1 | +40.3±1.1 | 0.965 | 0.2 | 19±1 | n.d. | n.d. |

*Estimated assuming valence (z) of −2.

RESULTS

DMT1 protein synthesis in vitro

All four isoforms of hDMT1 were transcribed and translated in a cell-free, coupled transcription–translation system in vitro (Figure 1B). The 1A/IRE(+) isoform was translated more efficiently than the 1B isoforms, and the 1A/IRE(−) isoform was only poorly translated. The 1A/IRE(+) and 1A/IRE(−) isoforms generated polypeptides of molecular mass≈73 kDa (predicted molecular mass=65 kDa), whereas the 1B isoforms generated smaller polypeptides of molecular mass≈61 kDa, as predicted (62 kDa). We also performed transcription–translation reactions in the presence of canine pancreatic microsomal membranes and isolated the membrane fraction at the end of the reaction. All four isoforms were incorporated into the membrane fraction (lanes marked M) to a similar degree (i.e. the protein densities of lanes marked M roughly correlate with the densities in the corresponding lanes marked X). The inclusion of microsomal membranes increased by approx. 10 kDa the molecular mass of each of the translation products, consistent with their glycosylation in vitro. The hDMT1 sequences each contain two consensus sites (N-X-T/S sequons) for N-linked glycosylation in the predicted fourth extracellular loop; in the 1A/IRE(+) isoform, these sites are at Asn-365 and Asn-378.

Expression of hDMT1 isoforms in cRNA-injected oocytes

We detected intense anti-DMT1 immunofluorescence at the plasma membrane of oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1, but not in control oocytes (Figure 1C). Whereas some cytoplasmic staining was visible in 1A/IRE(+) oocytes this is likely to be non-specific since it was also observed in control oocytes. Anti-DMT1 immunofluorescence was only barely detectable at the plasma membrane of oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(−)-DMT1; however, a modest increase in intracellular punctate labelling was also apparent in these oocytes. Strong plasma-membrane labelling was evident for the 1B/IRE(+) isoform, but only weak labelling was present in oocytes expressing 1B/IRE(−)-DMT1.

Since 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 was the most active isoform of hDMT1 tested in preliminary experiments, we examined the time course of 2 μM 55Fe2+ uptake (from 2 min to 2 h) in oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 (Figure 2A). 55Fe2+ uptake was linear at least up to 1 h. This held true provided that the volume of uptake medium was sufficient (results not shown); we used a maximum of 15 oocytes per 2 ml of medium. Subsequent metal-ion uptake experiments were performed over 10 min, within the time course of linear 55Fe2+ uptake. Each of the four hDMT1 isoforms exhibited iron transport activity but the 55Fe2+ uptake rates varied widely between these groups (Figure 2B). 1A/IRE(−)-DMT1 stimulated 55Fe2+ uptake above that observed for control oocytes but 55Fe2+ uptake for 1A/IRE(−) was only 2.3% that for the 1A/IRE(+) isoform that showed the most robust activity; both 1B isoforms exhibited intermediate levels of 55Fe2+ uptake activity. An identical pattern of 55Fe2+ transport activities was obtained in four additional independent preparations (results not shown).

In voltage-clamped oocytes (−70 mV) at extracellular pH (pHo) 5.5, 20 μM Fe2+ evoked large, reversible inward currents in oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1, but not in control oocytes (Figure 2C). Switching from pHo 7.5 to 5.5 also evoked small inward currents in oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1, consistent with a modest H+ leak in the absence of metal ion (see below). For 1A/IRE(+), the Fe2+-evoked current followed a curvilinear relationship with voltage, increasing with hyperpolarization (Figure 2D) up to −1000 nA at −150 mV. Evoked currents for 1A/IRE(+) exceeded the magnitudes of the evoked currents for each of the other isoforms; however, we found no qualitative differences in the current–voltage relationships among the various isoforms. This observation suggests that there are no differences between the four isoforms in terms of the rate-determining steps or the permeant ions involved in the transport cycle.

Following step changes in membrane potential (Vm), we observed for 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 pre-steady-state currents in the absence of metal ion. These were isolated from the capacitive transients and final steady-state currents as described in the Materials and methods section. The compensated currents thus obtained (illustrated for the 1A/IRE(+) isoform, Figure 2E) decayed with time constants (τ) of 15–40 ms. Pre-steady-state currents were integrated with time to obtain charge Q. The Q/Vm relationship for 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 was described by a single Boltzmann distribution around a midpoint (V0.5) of approx. +48 mV, with maximal charge (Qmax)≈50 nC and apparent valence (z) of the movable charge≈2 (Figure 2F and Table 1). The 1A/IRE(−) isoform exhibited only tiny pre-steady-state charge movements (Qmax≈0.8 nC) (Figure 2F and Table 1), whereas the 1B/IRE(+) and 1B/IRE(−) isoforms had Qmax of ∼10 nC and ∼6 nC respectively. We found no marked differences between isoforms in terms of the other pre-steady-state kinetic parameters, z or V0.5 (Table 1) or τ (results not shown). We previously observed pre-steady-state charge movements for the rat DMT1 and attributed these to two steps in the transport cycle, namely reorientation of the empty charged transporter and binding/dissociation of H+, within the plane of the membrane electric field [21]. Turnover rates of the transport cycle (determined as Qmax/–Imax) were similar among the four isoforms, 19–25 s−1 (Table 1).

We estimated from Qmax the number of functional DMT1 units expressed in the oocyte plasma membrane in individual oocytes using eqn (4), a method justified elsewhere [23]. 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 was expressed at a density (NT) of 1.6×1011 per oocyte (Table 1). Other isoforms were expressed at much lower density, relative to 1A/IRE(+): 1A/IRE(−), approx. 2%; 1B/IRE(+), 25%; and 1B/IRE(−), 13%. Relative transporter densities matched the relative iron transport activities measured either as 55Fe2+ uptake [2.3, 32 and 14%, relative to 1A/IRE(+), Figure 2B] or as the Fe2+-evoked current [1.7, 25 and 10%, relative to 1A/IRE(+), Table 1] and reflected in the similarity of the turnover rates (Table 1). Therefore all of the hDMT1 isoforms are equally efficient in terms of the rate at which they transport iron.

Transport mechanism of hDMT1

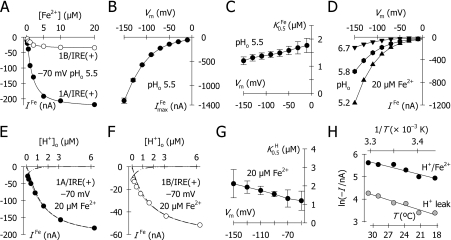

We determined the driving forces and saturation kinetics for hDMT1 by measuring Fe2+-evoked currents in oocytes expressing the 1A/IRE(+) or 1B/IRE(+) isoforms (Figure 3). The Fe2+-evoked currents were saturable, with half-maximal Fe2+ concentration (K0.5Fe) of 1.5 μM at −70 mV and pHo 5.5 (Figure 3A). The maximal current (ImaxFe) (Figure 3B) closely resembled the I/Vm relationships for both isoforms (Figure 2D) and increased with hyperpolarization, whereas K0.5Fe was only modestly voltage-dependent (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Mechanisms of hDMT1.

Data are for the 1A/IRE(+) isoform, except for 1B/IRE(+) data as indicated in (A, F). Error bars indicate the standard error of the regression for derived kinetic parameters. (A–C) Fe2+ saturation kinetics determined in individual oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 or 1B/IRE(+)-DMT1. Currents evoked by Fe2+ (−70 mV, pH 5.5) as a function of Fe2+ concentration (A) were fitted to eqn (1), which predicted, for 1A/IRE(+), ImaxFe=–227±7 nA, K0.5Fe=1.5±0.1 μM, and nHFe=1.3±0.1 (r2=0.997). For 1B/IRE(+), the derived parameters were ImaxFe=–36±2 nA, K0.5Fe=1.0±0.2 μM, and nHFe=1.0±0.2 (r2=0.988). (B, C) ImaxFe (B) and K0.5Fe (C) as a function of Vm for 1A/IRE(+). nHFe was close to 1 at all Vm (results not shown). (D–G) H+ saturation kinetics. (D) Currents evoked by 20 μM Fe2+ as a function of pHo, for 1A/IRE(+). For clarity, the currents at pH 6.7, 6.4 and 5.5 are omitted. (E) Fe2+-evoked currents at −70 mV were fitted to eqn (2) (solid grey line), which combines a H+-coupled current that follows a Hill function (dashed line) with ImaxH=−207±42 nA, K0.5H=1.3±0.5 μM, and nHH=1.3±0.3, and a facilitative (H+-uncoupled) Fe2+ current (iU) that follows an exponential decay (dashed-dotted line) with y-intercept (the Fe2+-evoked current at nominal [H+]o=0) at −26±3 nA. The [H+]o resulting in half-maximal inhibition of the facilitative Fe2+ current is given by ln(0.5)/−b and predicted to be 0.4±0.1 μM. The fit by eqn (2) (r2=1.000, P<0.001) represented a modest improvement over fitting the data using eqn (1) (results not shown; r2=0.993, P=0.002). (F) Fe2+-evoked currents as a function of [H+]o for 1B/IRE(+) were fitted by eqn (2), which predicted ImaxH=−65±12 nA, K0.5H=1.6±0.3 μM, nHH=1.0±0.7, y-intercept of IU at −26±3 nA, and ln(0.5)/−b of 0.4±0.1 μM (r2=0.999, P=0.002). See (E) for the key to fitted lines. (G) K0.5H as a function of Vm for 1A/IRE(+). (H) Temperature-dependence of 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1-mediated H+/Fe2+ co-transport and H+ leak. H+ leak activity (grey circles) was measured as the shift in baseline current upon switching from pH 7.5 to 5.5, and H+/Fe2+ co-transport activity (black circles) as the current evoked by 20 μM Fe2+ at pH 5.5 (−70 mV) following the manoeuvres illustrated in Figure 2(C). Data were fitted to eqn (5) that predicted Arrhenius activation energy (Ea) at 10.5±1.7 kcal/mol for H+/Fe2+ co-transport (ln A=23.2±2.9; r2=0.906, P=0.003). Ea for the H+ leak was 13.3±1.8 kcal/mol (ln A=26.3±3.0; r2=0.944, P=0.001). H+ leak data were not corrected for endogenous activity: IΔpH in control oocytes was typically approx. −5 nA, and Ea for IΔpH was previously determined in a control oocyte to be 5.9±0.4 kcal/mol [21].

At any given Vm, the Fe2+-evoked current was increased at lower pHo, in the range 7.0–5.2, and was accelerated by hyperpolarization at each pHo value tested (Figure 3D), i.e. the Fe2+-evoked currents were dependent on the H+ electrochemical potential gradient, consistent with a H+-coupled Fe2+ transport mechanism. H+ coupling in the rat DMT1 was confirmed by our observations that (i) iron transport at low pHo was associated with intracellular acidification [1,21] and (ii) the pre-steady-state currents were pHo-dependent indicating that H+ is a ligand [21]. In the latter, we also reported that rat DMT1 at higher pHo can mediate facilitative Fe2+ transport that is uncoupled from H+. Consistent with our finding for rat DMT1, the Fe2+-evoked currents for human 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 exhibited an incomplete dependence on H+ concentration (Figure 3E). 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1-mediated Fe2+ transport was activated by H+ but our data were better fitted by eqn (2) (see the Materials and methods section; K0.5H=1.3 μM; r2=1.000) – which predicts a H+-uncoupled, facilitative Fe2+ current that is inhibited at lower pH – than by eqn (1) (r2=0.993, results not shown). We also found that radiotracer iron uptake likewise exhibited an incomplete dependence on H+ concentration in oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1: 55Fe2+ uptake at pH 7.2 was 17%±1% (S.E.M.) that at pH 5.2 (results not shown).

The Hill coefficient for H+ (nHH) derived from the Fe2+-evoked currents was approx. 1 at −70 mV and did not change with Vm (results not shown). K0.5H increased modestly at hyperpolarized potentials compared with physiological Vm (−50 and −70 mV) (Figure 3G) as we observed for the rat DMT1 (results not shown), whereas mammalian Na+-coupled solute transporters are typically cation-saturated at hyperpolarized potentials (i.e. K0.5Na reaches a minimum at hyperpolarized Vm). The increased K0.5H at hyperpolarized Vm for DMT1 may be explained by a greater voltage dependence of the H+ leak pathway compared with H+/Fe2+ co-transport, a view that is supported by the increased H+/Fe2+ stoichiometry at hyperpolarized Vm [24].

The Fe2+-evoked currents mediated by 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 were temperature-dependent (Figure 3H). The Arrhenius activation energy for H+/Fe2+ co-transport was approx. 11 kcal/mol; which corresponds to Q10≈2 (the factor by which transport activity is increased with every 10 °C increase in temperature). Whereas the Fe2+-evoked currents mediated by 1B/IRE(+)-DMT1 were smaller than those mediated by the 1A/IRE(+) isoform, we found no difference in the basic mechanisms and saturation kinetics for the 1B isoform (Figures 3A and 3F and Table 1).

hDMT1 mediates a H+ leak in the absence of metal ion

We further explored the DMT1-mediated H+ leak current observed in the absence of metal ion (Figure 2C). We have shown previously that an influx of H+ can fully account for the H+-induced leak in rat DMT1 [21]. The H+ leak current mediated by 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 was saturable (results not shown), with ImaxH of −65±16 nA, and nHH≈1 (r2=0.992). The half-maximal H+ concentration (K0.5H) of the leak was 1.7±0.2 μM, close to that for H+/Fe2+ co-transport (1.3 μM). The H+ leak was temperature-dependent, with an activation energy (Ea) of approx. 13 kcal/mol (Figure 5H) no different from that co-transport (Ea≈11 kcal/mol). The saturability and temperature-dependence of the H+ leak pathway are therefore consistent with a carrier-mediated process, as for H+/Fe2+ co-transport.

Substrate profile of the 1A and 1B isoforms

We considered whether the additional N-terminal 29 amino-acid residues of the 1A isoforms (see Figure 1A) might confer a substrate profile that differed from that of the 1B isoforms. To test this, we examined the substrate profile of 1A/IRE(+) and 1B/IRE(+) DMT1 isoforms based on metal-ion-evoked currents as well as 55Fe2+ and 65Zn2+ radiotracer assays. In oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+), Co2+, Cd2+ and Mn2+ each evoked currents that were very similar to the Fe2+-evoked currents in magnitude and voltage-dependence (Figure 4A). Having confirmed radiotracer uptake for Fe2+, we provisionally conclude that Co2+, Cd2+ and Mn2+ are also substrates of 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1. Ni2+ and V3+ (or VO2+, the vanadyl cation) evoked smaller currents, and Pb2+ smaller still. Since their I/Vm relationships were qualitatively similar to that for Fe2+ we provisionally conclude that Ni2+, V3+ and Pb2+ are weaker substrates of 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1. Fluxes of several of these metal ions have yet to be demonstrated by a direct method. At physiological Vm (−30 to −70 mV), Zn2+ evoked larger currents than did Fe2+; however, the I/Vm relationship for Zn2+ deviated significantly from that for Fe2+: the Zn2+-evoked currents were not markedly stimulated by hyperpolarization and significant inward current persisted at positive Vm. To the extent tested (we did not test V3+), the substrate profile of 1B/IRE(+) (Figure 1B) was identical with that of 1A/IRE(+), so the additional amino acid residues of the 1A isoform do not confer an altered substrate profile.

The Zn2+ I/Vm relationship of 1B/IRE(+)-DMT1 resembled that of the 1A isoform and differed from the I/Vm relationships for the other metal ions tested (Figure 4B). This observation for both isoforms prompted us to test whether or not the atypical Zn2+-evoked currents derive from Zn2+ transport. 65Zn2+ uptake by oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+) (P=0.16) or 1B/IRE(+) (P=0.68) was not significantly different from that in control oocytes (Figure 4C) and the absolute values for 65Zn2+ uptake for each isoform was only 4–5% that for 55Fe2+ uptake. This was despite the fact that the Zn2+-evoked inward currents were more than double the magnitude of the Fe2+-evoked currents (Figures 4A and 4B) at −50 to −10 mV (i.e. the Vm range to be expected in non-voltage-clamped oocytes under the conditions described for Figure 4C). Therefore, although Zn2+ is a ligand for both the 1A and 1B isoforms of hDMT1, it is only poorly transported, if at all, relative to Fe2+. The preference for Fe2+ over Zn2+ is more marked for hDMT1 than it is for the rat homologue [21,25].

45Ca2+ uptake (at 2 μM) in oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-hDMT1 was induced 3-fold over that observed in control oocytes; however, the DMT1-induced Ca2+ transport activity (i.e. control-subtracted) was still only 0.3% the magnitude of the 55Fe2+ uptake mediated by DMT1 (Figure 4D). The DMT1-induced Ca2+ transport activity was significantly (but not completely) inhibited by excess (50 μM) Fe2+ or Zn2+ (results not shown). We conclude that hDMT1 is only very weakly reactive with Ca2+. We showed previously that Ca2+ is a weak inhibitor of the Fe2+-evoked current (and H+ leak) in oocytes expressing rat DMT1 (KiCa≈10 mM) [1], presumably since Ca2+ can occupy the transporter but is not efficiently transported. hDMT1 did not transport chromium-51 either in its 2+ or 3+ form (Figure 4D).

Ionic basis of the zinc-evoked current

The observation that hDMT1 mediates a large zinc-evoked current but not a significant zinc influx prompted us to examine the ionic basis of the zinc-evoked current. What other ionic fluxes may account for this current? We used a voltage-ramp protocol to determine reversal potentials (Vr) in oocytes expressing 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 under varying ionic conditions (Figure 5A). Experiments were performed in the presence of niflumic acid (a chloride channel blocker) to minimize the contribution of the endogenous Cl− channel that is commonly up-regulated as a result of high expression of exogenous channels or transporters in oocytes [26,27]. Varying the concentration ratio ([ion]o/[ion]i) of a permeant ion is expected to result in a shift in Vr according to the Nernst equation (eqn 6) in which z is the ionic valence, and R, T and F have their usual thermodynamic meanings.

Thus, at the ambient temperature (22–23 °C) for voltage-clamp experiments, the Nernst potential predicts that Vr shift +59 mV per 10-fold increase in extracellular concentration of a permeant univalent cation, and +30 mV for a permeant divalent cation; smaller shifts are anticipated when there is more than one permeant ion. Varying the concentration ratio for zinc resulted in only minimal changes in Vr (1.3±1.0 mV per 10-fold change in [Zn2+]o), so we predict that only a tiny fraction of the inward current derives from an influx of Zn2+. Instead, most of the Zn2+-evoked inward current derives from H+ influx as judged from the dependence of Vr on pHo (40.3 mV per pH unit), and the remainder, largely from Cl− efflux (Figure 5A). We have previously reported preliminary evidence that metal ions induce a Cl− current in oocytes expressing the G185R (Belgrade) rat DMT1 mutant in which metal-ion transport is disrupted, and that DMT1-mediated Fe2+ transport may be facilitated by Cl− [28].

Based on the slopes of the Vr/log10[ion] relationships and using the function Pr=(slope×|z|)/59 mV, we predict relative permeabilities (Pr) of 0.7 (H+), 0.2 (Cl−) and 0.04 (Zn2+). As to the remaining 10% or so of the Zn2+-evoked current, we also considered (i) Ca2+, since Xu et al. [29] proposed that a Ca2+ permeability was associated with the G185R-DMT1 (Belgrade/mk) mutant, and (ii) Na+, since SMF1 – a yeast homologue of DMT1 – mediates a Na+ current [24]. Vr did not vary with [Ca2+]o (−0.1±1.2 mV/log10[Ca2+]o; r2=0.002; P=0.914) or with [Na+]o (−1.7±6.2/log10[Na+]o; r2=0.018; P=0.803) (results not shown), indicating that neither Ca2+ nor Na+ currents contribute to the zinc-evoked current in DMT1-expressing oocytes. For increased sensitivity in testing for a Na+ influx, we measured radiotracer 22Na+ uptake in DMT1-expressing oocytes. We used as a positive control the rabbit Na+-dependent glucose transporter SGLT1 for which glucose transport is known to be tightly coupled with Na+ transport [30]. 22Na+ uptake in the absence of sugar was modestly increased in oocytes expressing SGLT1 compared with control oocytes (Figure 5B), consistent with the Na+ leak observed for SGLT1 in the absence of sugar [30]. The addition of sugar stimulated 22Na+ uptake 9-fold over control. In contrast, DMT1 expression did not stimulate 22Na+ uptake either under conditions supporting the H+ leak or when Fe2+ or Zn2+ was added to the medium (Figure 5B). Therefore DMT1, unlike its yeast homologue SMF1, does not mediate Na+ transport either in the H+ leak or H+/Fe2+ co-transport modes; nor does Na+ participate in the Zn2+-evoked current.

DISCUSSION

Our results confirm that each of the four hDMT1 isoforms, 1A/IRE(+), 1A/IRE(−), 1B/IRE(+) and 1B/IRE(−), can function as metal-ion transporters when expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The four isoforms are equally efficient transporters since iron transport activity correlated with the abundance of the protein in the oocyte plasma membrane for each isoform. Whereas some immunofluorescence for IRE(−) isoforms appeared intracellular, indicating differences in targeting, much of the variability in plasma-membrane expression appears to have arisen from differing transcriptional or translational efficiency as judged from protein synthesis in a cell-free system. When we used cRNA as the template in a translation system in vitro (results not shown), we observed protein densities that matched those from the coupled transcription–translation system (from cDNA) (Figure 1B). This observation suggests that DMT1 isoforms differ in their translational efficiency and would indicate that it is therefore unsafe to make conclusions concerning the relative activity of DMT1 isoforms based solely on isoform-specific mRNA abundances. Alternatively, this result may have been due to differences in mRNA stability between the isoforms. However, this seems unlikely as the coupled transcription/translation system contained a ribonuclease inhibitor.

Radiotracer assays and voltage-clamp data in cRNA-injected oocytes revealed that 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 mediates membrane transport of Fe2+ with moderately high affinity for Fe2+ (K0.5Fe=1–2 μM). The basic mechanisms of human 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 are reminiscent of those of the rat 1A/IRE(+) isoform [21] (NCBI Entrez accession number AF008439) that was isolated from rat intestine by expression cloning [1]; the amino acid sequence of that clone was originally misreported as starting from the ATG codon in exon 2, but this was later clarified [7]. hDMT1-mediated Fe2+ transport was temperature-dependent and driven by the H+ electrochemical potential gradient. Although Fe2+ transport is maximally stimulated at low pHo − with K0.5H≈1 μM (i.e. pH 6.0) at physiological membrane potential (−70 to −50 mV) – the Fe2+-evoked currents for human 1A/IRE(+) and 1B/IRE(+) isoforms were not completely dependent on the transmembrane H+ gradient (Figures 3E and 3F). This feature was previously demonstrated for rat 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 in which Fe2+ transport at pHo>7.0 was not coupled with a H+ flux. Whereas duodenal mucosal cell surface pH is 6.7, the microclimate pH reaches 6.0 in human proximal jejunum in vivo [31]. DMT1 should thus be expected to mediate apical iron uptake in the duodenum in spite of only a modest transmembrane H+ gradient and meanwhile serve as an effective scavenger of the available Fe2+ in the proximal jejunum.

The substrate profile of 1A/IRE(+)-DMT1 includes (ranked on currents) Fe2+, Cd2+, Co2+, Mn2+>Ni2+, V3+ (or VO2+)>Pb2+. That Co2+ and Mn2+ are also transported substrates of DMT1 has been demonstrated from 60Co2+ and 54Mn2+ uptakes in oocytes expressing rat DMT1 [32], and 54Mn2+ uptake in CHO (Chinese-hamster ovary) cells expressing mouse DMT1 [33]. The latter study also demonstrated DMT1-mediated Fe2+, Co2+ and Mn2+ transport using a fluorescence assay. hDMT1 does not mediate significant Zn2+ transport and the idea that DMT1 should not be considered a significant physiological route of zinc absorption is discussed elsewhere [6]. Zn2+ does, however, evoke a current that comprises H+ and Cl− conductances but not a significant Zn2+ conductance. Zn2+ only weakly inhibits DMT1-mediated Fe2+ transport [21,34]; however, the Ki with which it does so matches the K0.5 for 65Zn2+ transport (B. Mackenzie, unpublished work) indicating that Fe2+ and Zn2+ share a common binding site. The DMT1-mediated H+ flux is known to exceed that expected for stoichiometric H+/Fe2+ coupled transport [24] and we speculate that the same uncoupled H+ flux proceeds in the presence of Zn2+, despite Zn2+ being only poorly transported relative to Fe2+. Since the Zn2+-evoked current is primarily a H+ influx, the presence of Zn2+ might be expected to short-circuit the H+ electrochemical gradient driving Fe2+ transport; however, this is unlikely to be of physiological consequence since Zn2+ is only a weak inhibitor of DMT1-mediated Fe2+ uptake in vitro [21,34]. Ca2+ transport via 1A/IRE(+)-hDMT1 was only barely detectable in vitro and should not be expected to be physiologically relevant; however, DMT1-mediated Fe2+ transport may be modestly inhibited by high (millimolar) Ca2+ concentrations [1] such as may be periodically reached in the gut lumen. 1A/IRE(+)-hDMT1 cannot transport chromium (II or III).

The 1A/IRE(+) and 1B/IRE(+) isoforms of hDMT1 have an identical substrate profile and operate by identical kinetic mechanisms. That is to say, the additional 29-amino-acid region at the N-terminus of the 1A isoform does not confer any change in substrate selectivity or other functional properties of DMT1. All four isoforms transport Fe2+ at the same turnover rate and exhibit no differences in their functional properties, permeant ions or rate-limiting steps. Instead, we expect that the existence of variant transcripts serves the needs of particular cell types for discrete subcellular targeting and regulation by discrete cues. Garrick et al. [35] recently reported that the tetracycline-inducible expression of 1B/IRE(–) isoform (described there as 2/–IRE) in a human embryonic kidney epithelial cell line was detected predominantly in intracellular compartments, whereas the 1A/IRE(+) isoform was detected predominantly at the plasma membrane; however, the two isoforms displayed similar properties in terms of Mn2+ or Fe2+ transport.

We anticipated that the region of the peptide coded by exon 1A might contain a signal sequence directing trafficking of the 1A isoforms to the plasma membrane; however, the GvH algorithm [36] of the PSORT II suite (accessed at http://psort.hgc.jp) did not identify an N-terminal signal sequence in any of the four hDMT1 isoforms, and the k-NN prediction [37] (accessed at the same site) scored the 1A isoforms only modestly higher (73.9%) than the 1B isoforms (69.6%) in their probability of plasma-membrane targeting. Plasma-membrane immunostaining of 1B/IRE(+) was less intense than that for 1A/IRE(+) (Figure 1C); however, this may be explained by a reduced translational efficiency for 1B/IRE(+) relative to 1A/IRE(+) (Figure 1B) without necessarily pointing to differences in targeting to the plasma membrane in the oocyte system.

We observed faint punctiform staining in oocytes expressing the non-IRE isoforms, consistent with the idea that plasma-membrane targeting or internalization of DMT1 protein is directed by C-terminal sequence determinants. In agreement with this view, a conserved C-terminal motif (Y555LLNT) in the human or mouse 1B/IRE(−) isoform (the predominant isoform expressed in erythroid precursors) is required for the internalization and early-endosomal localization of this isoform [38,39]. In contrast, a larger fraction of the 1A/IRE(+) isoform (the predominant isoform in epithelial cells) is expressed at the plasma membrane; 1A/IRE(+) is internalized more slowly than is 1B/IRE(−), it is not efficiently recycled and is targeted to lysosomes upon its internalization [40]. Non-IRE DMT1 isoforms have been shown to also undergo translocation to the nucleus in cultured neural cells; the signal is yet to be identified but it is clear that the consensus nuclear localization signal found in the 1A exon is not responsible for nuclear targeting of the protein [41]. The IRE-containing DMT1 isoforms are strongly iron-regulated [7,42,43], presumably via IRE-mediated effects on mRNA stability. Adding to the complexity, the presence of the 1A exon also contributes to regulation by iron status [7]. It is not clear if specific DMT1 isoforms, in at least certain cell types, can respond to regulatory cues other than Fe2+.

Discrete subcellular targeting of the DMT1 isoforms may rely on specific protein–protein interactions depending on short N- and C-terminal peptide sequences that differ between the isoforms. The literature contains at least one precedent for a membrane transporter: the neuronal GlyT2 (glycine transporter 2) possesses short N- and C-terminal peptide sequences that interact with specific binding partners directing its subcellular localization [44,45].

In summary, our study shows that the 1A/IRE(+) isoform of hDMT1 is a divalent metal-ion transporter that is energized by the H+ electrochemical potential gradient. Its preferred substrates may include Fe2+ (K0.5Fe of 1–2 μM), Co2+ and Mn2+, but not Zn2+. The toxic heavy metal Cd2+ also evoked large currents. Our results reveal that all four isoforms of hDMT1 function as iron transporters of equivalent transport efficiency. N- and C-terminal sequence variations among the DMT1 isoforms therefore do not alter DMT1 functional properties but instead are expected to direct the appropriate cell-specific subcellular targeting and regulation by discrete cues.

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful to Professor Matthias W. Hentze (EMBL Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany) for fruitful discussions throughout the course of this study and for helpful comments on this paper. We thank Ali Shawki (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, U.S.A.) for his help in the laboratory. This study was supported by NIH (National Institutes of Health) grant number R01-DK057782 (to M.A.H.) and the University of Cincinnati (to B.M.).

References

- 1.Gunshin H., Mackenzie B., Berger U. V., Gunshin Y., Romero M. F., Boron W. F., Nussberger S., Gollan J. L., Hediger M. A. Cloning and characterization of a proton-coupled mammalian metal-ion transporter. Nature. 1997;388:482–488. doi: 10.1038/41343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hentze M. W., Muckenthaler M. U., Andrews N. C. Balancing acts: molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2004;117:285–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunshin H., Fujiwara Y., Custodio Á. O., Direnzo C., Robine S., Andrews N. C. Slc11a2 is required for intestinal iron absorption and erythropoiesis but dispensable in placenta and liver. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1258–1266. doi: 10.1172/JCI24356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrick M. D., Garrick L. M. Divalent metal transporter DMT1 (SLC11A2) In: Bröer S., Wagner C. A., editors. Membrane Transporter Diseases. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2004. pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie B., Hediger M. A. SLC11 family of H+-coupled metal-ion transporters NRAMP1 and DMT1. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2004;447:571–579. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackenzie B., Garrick M. D. Iron imports. II. Iron uptake at the apical membrane in the intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G981–G986. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00363.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubert N., Hentze M. W. Previously uncharacterized isoforms of divalent metal transporter (DMT)-1: implications for regulation and cellular function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:12345–12350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192423399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee P. L., Gelbart T., West C., Halloran C., Beutler E. The human Nramp2 gene: characterization of the gene structure, alternative splicing, promoter region and polymorphisms. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 1998;24:199–215. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1998.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canonne-Hergaux F., Gruenheid S., Ponka P., Gros P. Cellular and subcellular localization of the Nramp2 iron transporter in the intestinal brush border and regulation by dietary iron. Blood. 1999;93:4406–4417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pantopoulos K. Iron metabolism and the IRE/IRP regulatory system: an update. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1012:1–13. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takanaga H., Mackenzie B., Suzuki Y., Hediger M. A. Identification of mammalian proline transporter SIT1 (SLC6A20) with characteristics of classical system Imino. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:8974–8984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hediger M. A., Coady M. J., Ikeda T. S., Wright E. M. Expression cloning and cDNA sequencing of the Na+/glucose cotransporter. Nature. 1987;330:379–381. doi: 10.1038/330379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright E. M., Turk E. The sodium/glucose cotransport family SLC5. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2004;447:510–518. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takanaga H., Mackenzie B., Peng J.-B., Hediger M. A. Characterization of a branched-chain amino-acid transporter SBAT1 (SLC6A15) that is expressed in human brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;337:892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjellqvist B., Hughes G. J., Pasquali C., Paquet N., Ravier F., Sanchez J. C., Frutiger S., Hochstrasser D. The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:1023–1031. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501401163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blom N., Sicheritz-Ponten T., Gupta R., Gammeltoft S., Brunak S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics. 2004;4:1633–1649. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackenzie B. Selected techniques in membrane transport. In: Van Winkle L. J., editor. Biomembrane Transport. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 327–342. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrmann T., Muckenthaler M., Van Der H. F., Brennan K., Gehrke S. G., Hubert N., Sergi C., Grone H. J., Kaiser I., Gosch I., et al. Iron overload in adult Hfe-deficient mice independent of changes in the steady-state expression of the duodenal iron transporters DMT1 and Ireg1/ferroportin. J. Mol. Med. 2004;82:39–48. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0508-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Q., Kandegedara A., Xu Y., Rorabacher D. B. Avoiding interferences from Good's buffers: a contiguous series of noncomplexing tertiary amine buffers covering the entire range of pH 3–11. Anal. Biochem. 1997;253:50–56. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandegedara A., Rorabacher D. B. Non complexing tertiary amines as ‘better’ buffers covering the range of pH 3–11. Temperature dependence of their acid dissociation constants. Anal. Chem. 1999;71:3140–3144. doi: 10.1021/ac9902594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackenzie B., Ujwal M. L., Chang M.-H., Romero M. F., Hediger M. A. Divalent metal-ion transporter DMT1 mediates both H+-coupled Fe2+ transport and uncoupled fluxes. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2006;451:544–558. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1494-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hazama A., Loo D. D. F., Wright E. M. Presteady-state currents of the rabbit Na+/glucose cotransporter (SGLT1) J. Membr. Biol. 1997;155:175–186. doi: 10.1007/s002329900169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zampighi G. A., Kreman M., Boorer K. J., Loo D. D. F., Bezanilla F., Chandy G., Hall J. E., Wright E. M. A method for determining the unitary functional capacity of cloned channels and transporters expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J. Membr. Biol. 1995;148:65–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00234157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X.-Z., Peng J.-B., Cohen A., Nelson H., Nelson N., Hediger M. A. Yeast SMF1 mediates H+-coupled iron uptake with concomitant uncoupled cation currents. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:35089–35094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marciani P., Trotti D., Hediger M. A., Monticelli G.-L. Modulation of DMT1 activity by redox compounds. J. Membr. Biol. 2004;197:91–99. doi: 10.1007/s00232-003-0644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackenzie B., Schäfer M. K. H., Erickson J. D., Hediger M. A., Weihe E., Varoqui H. Functional properties and cellular distribution of the System A glutamine transporter SNAT1 support specialized roles in central neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:23720–23730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzounopoulos T., Maylie J., Adelman J. P. Induction of endogenous channels by high levels of heterologous membrane proteins in Xenopus oocytes. Biophys. J. 1995;69:904–908. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79964-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackenzie B., Ujwal M. L., Hediger M. A. H+-coupled metal-ion transport mediated by DCT1 is facilitated by chloride. Biophys. J. 2001;80:17a (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu H., Jin J., DeFelice L. J., Andrews N. C., Clapham D. E. A spontaneous, recurrent mutation in divalent metal transporter-1 exposes a calcium entry pathway. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E50. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackenzie B., Loo D. D. F., Wright E. M. Relationships between Na+/glucose cotransporter currents and fluxes. J. Membr. Biol. 1998;162:101–106. doi: 10.1007/s002329900347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEwan G. T. A., Lucas M. L., Mathan V. I. A combined TDDA-PVC pH and reference electrode for use in the upper small intestine. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 1990;14:16–20. doi: 10.3109/03091909009028758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sacher A., Cohen A., Nelson N. Properties of the mammalian and yeast metal-ion transporters DCT1 and Smf1p expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J. Exp. Biol. 2001;204:1053–1061. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forbes J. R., Gros P. Iron, manganese, and cobalt transport by Nramp1 (Slc11a1) and Nramp2 (Slc11a2) expressed at the plasma membrane. Blood. 2003;102:1884–1892. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrick M. D., Singleton S. T., Vargas F., Kuo H., Zhoa L., Knöpfel M., Davidson T., Costa M., Paradkar P. N., Roth J. A., Garrick L. M. DMT1: which metals does it transport? Biol. Res. 2006;39:79–85. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602006000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrick M. D., Kuo H. C., Vargas F., Singleton S., Zhao L., Smith J. J., Paradkar P., Roth J. A., Garrick L. M. Comparison of mammalian cell lines expressing distinct isoforms of divalent metal transporter 1 in a tetracycline-regulated fashion. Biochem. J. 2006;398:539–546. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakai K., Horton P. PSORT: a program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:34–36. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horton P., Nakai K. Better prediction of protein cellular localization sites with the k nearest neighbors classifier. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1997;5:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lam-Yuk-Tseung S., Touret N., Grinstein S., Gros P. Carboxyl-terminus determinants of the iron transporter DMT1/SLC11A2 isoform II (-IRE/1B) mediate internalization from the plasma membrane into recycling endosomes. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12149–12159. doi: 10.1021/bi050911r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabuchi M., Tanaka N., Nishida-Kitayama J., Ohno H., Kishi F. Alternative splicing regulates the subcellular localization of divalent metal transporter 1 isoforms. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:4371–4387. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lam-Yuk-Tseung S., Gros P. Distinct targeting and recycling properties of two isoforms of the iron transporter DMT1 (NRAMP2, Slc11A2) Biochemistry. 2006;45:2294–2301. doi: 10.1021/bi052307m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo H. C., Smith J. J., Lis A., Zhao L., Gonsiorek E. A., Zhou X., Higgins D. M., Roth J. A., Garrick M. D., Garrick L. M. Computer-identified nuclear localization signal in exon 1A of the transporter DMT1 is essentially ineffective in nuclear targeting. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;76:497–511. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rolfs A., Bonkovsky H. L., Kohlroser J. G., McNeal K., Sharma A., Berger U. V., Hediger M. A. Intestinal expression of genes involved in iron absorption in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G598–G607. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00371.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunshin H., Allerson C. R., Polycarpou-Schwarz M., Rofts A., Rogers J. T., Kishi F., Hentze M. W., Rouault T. A., Andrews N. C., Hediger M. A. Iron-dependent regulation of the divalent metal ion transporter. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:309–316. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohno K., Koroll M., El Far O., Scholze P., Gomeza J., Betz H. The neuronal glycine transporter 2 interacts with the PDZ domain protein syntenin-1. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2004;26:518–529. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horiuchi M., Loebrich S., Brandstaetter J. H., Kneussel M., Betz H. Cellular localization and subcellular distribution of Unc-33-like protein 6, a brain-specific protein of the collapsin response mediator protein family that interacts with the neuronal glycine transporter 2. J. Neurochem. 2005;94:307–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackenzie B., Takanaga H., Hubert N., Hentze M. W., Hediger M. A. Functional characterization of multiple isoforms of the human iron transporter DMT1. FASEB J. 2004;18:A692–A693 (abstract). [Google Scholar]