Abstract

Metallo-β-lactamase enzymes (MβL) are encoded by transferable genes, which appear to spread rapidly among gram-negative bacteria. The objective of this study was to develop a multiplex real-time PCR assay followed by a melt curve step for rapid detection and identification of genes encoding MβL-type enzymes based on the amplicon melting peak. The reference sequences of all genes encoding IMP and VIM types, SPM-1, GIM-1, and SIM-1 were downloaded from GenBank, and primers were designed to obtain amplicons showing different sizes and melting peak temperatures (Tm). The real-time PCR assay was able to detect all MβL-harboring clinical isolates, and the Tm-assigned genotypes were 100% coincident with previous sequencing results. This assay could be suitable for identification of MβL-producing gram-negative bacteria by molecular diagnostic laboratories.

Since the first report of acquired metallo-β-lactamase (MβL) in Japan in 1994 (15), genes encoding IMP- and VIM-type enzymes have spread rapidly among Pseudomonas spp. (1, 5, 10, 13, 14, 16, 18, 22-24), Acinetobacter spp. (3, 4, 17, 21, 29), and strains of Enterobacteriaceae (6, 8, 11, 12, 20, 28). Moreover, new MβL types have been described, such as SPM (25), GIM (2), and, more recently, SIM (9).

The prevalence of MβL-producing gram-negative bacilli has increased in some hospitals, particularly among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. (21, 23, 27). Since MβL production may confer phenotypic resistance to virtually all clinically available β-lactams, the continued spread of MβL is a major clinical concern (26). The aim of this study was to develop a multiplex real-time PCR assay followed by a melt curve step for rapid detection and identification of genes encoding the MβL-type enzymes so far described. The MβL type identification was based on the characteristic amplicon melting peak.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MβL-harboring clinical isolates and MβL-negative control strains.

The strains used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The MβL genotypes of the clinical isolates of gram-negative nonfermentative and fermentative bacteria harboring MβL were previously characterized by PCR and sequencing. When applicable, these clinical isolates were also previously molecularly typed to ensure that genetically unrelated strains were used. Additionally, several American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) reference strains and laboratory strains were used as MβL-negative controls (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

MβL-harboring clinical isolates used during the validation process

| Clinical isolate | MβL-encoding gene | Reference or accession no. | Strain no. | Ribogroup |

Tm of amplicon

|

Amplicon GC content (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Practical | ||||||

| Serratia marcescens | blaIMP-1 | 15 | TN9106 | NAa | 77.9 | 77.5 | 38.30 |

| Pseudomonas putida | blaIMP-1 | AM283489 | 48-12346A | NA | 77.9 | 77.5 | 38.30 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | blaIMP-1 | 2a | A199 | NA | 77.9 | 77.5 | 38.30 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | blaIMP-1 | AJ640197 | 48-696D | NA | 77.9 | 77.5 | 38.30 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaIMP-1 | 19 | A5386 | NA | 77.9 | 77.5 | 38.30 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | blaIMP-1 | 11 | A13309 | NA | 77.9 | 77.5 | 38.30 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaIMP-5 | 19a | 115-10639A | NA | 77.5 | 76.5 | 37.23 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaIMP-13 | 22 | 86-14571 | NA | 77.1 | 76.0 | 36.17 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaIMP-16 | 14 | 101-4704 | 164-7 | 77.3 | 76.5 | 36.70 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaIMP-16 | This study | P3987 | 164-8 | 77.3 | 76.5 | 36.70 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaIMP-18 | This study | A3486 | NA | 76.4 | 76.0 | 34.57 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaVIM-1 | 23 | 75-3636C | NA | 87.1 | 88.5 | 57.33 |

| E. cloacae | blaVIM-1 | AM183120 | 75-10433A | NA | 87.1 | 88.5 | 57.33 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaVIM-2 | 23 | 81-11963A | NA | 86.9 | 88.0 | 56.81 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaVIM-2 | 13 | 49-4583C | NA | 86.9 | 88.0 | 56.81 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaVIM-2 | This study | A1254 | NA | 86.9 | 88.0 | 56.81 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaVIM-7 | 24 | 7-406 | NA | 86.2 | 87.5 | 55.00 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 25 | 48-1997A | 72-3 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A3488 | 88-2 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A2535 | 77-2 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A3301 | 105-3 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A3307 | 106-4 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A3302 | 105-4 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A3304 | 97-7 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A3300 | 105-1 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A2839 | 88-1 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A3309 | 105-5 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaSPM-1 | 7 | A2526 | 78-4 | 83.8 | 83.5 | 47.62 |

| P. aeruginosa | blaGIM-1 | 2 | 73-5671 | NA | 72.2 | 72.0 | 34.72 |

| A. baumannii | blaSIM-1 | 9 | 03-9-T104 | NA | 80.4 | 80.5 | 39.89 |

NA, not applicable.

TABLE 2.

ATCC reference and laboratory strains of gram-negative bacteria used during the validation process as MβL-negative control strainsa

| Organism | Strain no. | Practical amplicon Tm |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | PA01 | 86.0 |

| Escherichia coli | DH5α | 87.0 |

| E. coli | DH10B | 86.5 |

| E. coli | K-12 | 86.5 |

| E. coli | ATCC 25922 | 85.5 |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | ATCC 33305 | 85.5 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | ATCC 13048 | 86.5 |

| P. aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 | 86.0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 700603 | 86.5 |

| Neisseria meningitidis | ATCC 13090 | 86.0 |

| Neisseria perflava | ATCC 14799 | 86.0 |

| Neisseria lactamica | ATCC 49142 | 86.0 |

| Neisseria sicca | ATCC 29193 | 86.0 |

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium | ATCC 14028 | 86.0 |

The 16S rRNA gene was the target gene in each case.

DNA preparation.

The microorganisms were grown on blood agar plates overnight at 37°C to ensure colony purity. Three or four bacterial colonies were taken from the blood agar plates and suspended in 200 μl of DNase/RNase-free distilled water (Invitrogen, CA). Two microliters of this suspension was used as templates for further amplification.

Primer design.

The currently available reference sequences of the MβL-encoding IMP- and VIM-type (http://www.lahey.org/studies/), SPM-1 (AJ492820), GIM-1 (AJ620678), and SIM-1 (AY887066) genes were downloaded from GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Based on the comprehensive analyses and alignments of each MβL type, primers were designed to yield amplicons showing different sizes and melting peak temperatures (Tm) separated by at least 1°C. Predicted amplicon sizes and Tm were determined by the Lasergene software package (DNASTAR, Madison, WI).

Additionally, a primer pair targeting the consensus region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was included in the reaction mixture as a PCR internal-control target. Primer pairs were evaluated in a single format (using a primer concentration of 0.5 μM) to ensure that they correctly amplified their respective loci and that the amplicons showed the expected Tm. Subsequently, the multiplex format was optimized by assaying different primer pair concentrations. The primer sequences, positions, and concentrations, and the sizes of the corresponding amplicons, are given in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Target | Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Concn (μM)a | Amplicon size (bp) | Amplicon practical Tmb | Positionc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaIMP type | IMPgen-F1 | GAATAG(A/G)(A/G)TGGCTTAA(C/T)TCTC | 1.0 | 188 | 76.0-77.5 | 308-328 |

| IMPgen-R1 | CCAAAC(C/T)ACTA(G/C)GTTATC | 495-478 | ||||

| blaVIM type | VIMgen-F2 | GTTTGGTCGCATATCGCAAC | 0.1 | 382 | 87.5-88.5 | 157-176 |

| VIMgen-R2 | AATGCGCAGCACCAGGATAG | 538-519 | ||||

| blaGIM-1 | GIM-F1 | TCAATTAGCTCTTGGGCTGAC | 0.1 | 72 | 72.0 | 574-594 |

| GIM-R1 | CGGAACGACCATTTGAATGG | 645-626 | ||||

| blaSIM-1 | SIM-F1 | GTACAAGGGATTCGGCATCG | 0.1 | 569 | 80.5 | 126-145 |

| SIM-R1 | TGGCCTGTTCCCATGTGAG | 694-676 | ||||

| blaSPM-1 | SPM-F1 | CTAAATCGAGAGCCCTGCTTG | 0.1 | 798 | 83.5 | 11-31 |

| SPM-R1 | CCTTTTCCGCGACCTTGATC | 808-789 | ||||

| 16S rRNA | 16S-8F | AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | 0.04 | 1,499 | 86.0-87.0 | 8-27 |

| 16S-1493R | ACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT | 1512-1492 |

Final concentration in the multiplex real-time PCR.

Practical Tm of the amplicon obtained from the evaluated strains.

Position numbers correspond to the nucleotides of the coding sequences.

Multiplex real-time PCR.

Amplification was performed in a 48-μl mixture containing 25 μl of Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix (Platinum Taq DNA polymerase, SYBR Green I dye, Tris-HCl, KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 400 μM dGTP, 400 μM dATP, 400 μM dCTP, 800 μM dUTP, uracil DNA glycosylase, and stabilizers) (Invitrogen, CA), six pairs of primers at their respective concentrations (Table 3), and 2 μl of the template by using the DNA Engine Opticon 2 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA). The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 53°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and a melt curve step (from 68°C, gradually increasing 0.5°C/s to 95°C, with acquisition data every 1 s). Melt curves were then converted into melting peaks by plotting the negative derivative of fluorescence versus temperature (−dF2/dT versus T and −dF3/dT versus T).

Multiplex real-time PCR validation.

In order to assess the accuracy of the assay, 44 bacterial strains were blindly tested after real-time PCR optimization (Tables 1 and 2).

Multiplex real-time PCR sensitivity.

The sensitivity of the reaction was estimated by dilution experiments. Briefly, one representative of each MβL-harboring clinical isolate was suspended in DNase/RNase-free distilled water to a density corresponding to a McFarland turbidity standard of 1.0 (3 × 108 CFU/ml). These suspensions were used to prepare serial 10-fold dilutions using DNase/RNase-free distilled water.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

When different strains were submitted to the real-time PCR assay, differences in the Tm of the amplicons were observed for strains harboring blaIMP-type allelic variants (from 76.0°C to 77.5°C) as well as for those harboring blaVIM-type allelic variants (from 87.5°C to 88.5°C) (Table 1). These differences in Tm will be observed mainly for amplicons generated from blaIMP-type genes, since the GC contents of the amplicons generated will be more divergent than those for blaVIM-type genes (Table 1).

Allelic variants for the remaining MβL types (blaSPM-1, blaGIM-1, and blaSIM-1) have not been found yet. For this reason, only one clinical isolate harboring blaGIM-1 and one harboring blaSIM-1 were used during the validation process. The theoretical and practical Tm obtained were very similar, and no Tm differences were observed when several genetically unrelated blaSPM-1-harboring P. aeruginosa isolates were submitted to the assay (Table 1).

When the negative-control ATCC reference strains and laboratory strains were submitted to the assay, the melt curve analysis showed only one melting peak varying from 85.5°C to 86.5°C (Table 2). These melting peaks were consistent with the Tm of the amplicon generated by the primers targeting the conserved sequences of the 16S rRNA gene. This internal-control primer pair was used at a lower concentration than the primers targeting the MβL genes; thus, the latter would have preference during the amplification reaction. This strategy was employed to avoid double amplification, which could compromise the melt curve analysis.

The real-time PCR sensitivity experiment showed that the assay was capable of detecting the16S rRNA target gene at a dilution corresponding to 6 × 103 CFU per reaction; blaSPM, blaVIM, blaSIM, and blaIMP at 6 × 102 CFU per reaction; and blaGIM at 6 × 101 CFU per reaction (data not shown). Additionally, the lowest detection limits of the target genes were represented by the cycle threshold values of 34.62, 34.11, 33.66, 32.69, 32.58, and 28.86 for the16S rRNA, blaSPM, blaGIM, blaIMP, blaSIM, and blaVIM genes, respectively. This suggests that the assay as developed is sufficiently robust, even when the bacterial cells suspended in water are used as the template.

Although the assay was developed to detect all MβL-encoding genes, we could not submit strains harboring all the blaIMP and blaVIM allelic variants, since we do not have access to all of them. We also acknowledge the possibility of future assay limitations once more MβL types or newly emerging MβL allelic variants are detected, requiring a possible assay reconfiguration.

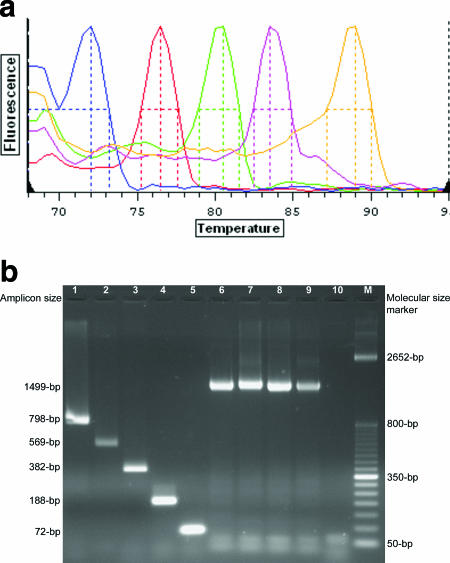

The assay was able to detect and identify all MβL-harboring strains evaluated. It is a single-tube reaction, technically simple, performed in only 2 h after colony selection. The Tm-assigned MβL genotypes are easily interpreted (Fig. 1a) and may be suitable for the detection of MβL-producing gram-negative bacteria by molecular diagnostic laboratories. Furthermore, the assay may also be performed through a conventional amplification reaction, followed by visualization of the amplicons by using a UV light box after electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

(a) Characteristic melting peaks (colored lines) of the amplicons generated by primers targeting the five MβL types so far described when MβL-harboring clinical isolates were submitted to the real-time PCR assay. Colors and genes targeted, from left to right, are as follows: blue, blaGIM-1 (Tm, 72.0°C); red, blaIMP-type genes (Tm, 76.5°C); green, blaSIM-1 (Tm, 80.5°C); pink, blaSPM-1 (Tm, 83.5°C); orange, blaVIM-type genes (Tm, 89.0°C). (b) Amplicons generated by primers targeting the five MβL types and the internal-control gene (16S rRNA). Visualization was performed in a UV light box after electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide. Lane 1, SPM-1 amplicon (798 bp; strain 48-1997A); lane 2, SIM-1 amplicon (569 bp; strain 03-9-T104); lane 3, VIM-type amplicon (382-bp; strain 7-406); lane 4, IMP-type amplicon (188 bp; strain 48-696D); lane 5, GIM-1 amplicon (72 bp; strain 73-5671); lanes 6 to 9, the internal-control amplicon (1,499 bp; strains A. calcoaceticus ATCC 33305, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, and Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13048, respectively); lane 10, negative control; lanes M, molecular size markers (50-bp DNA ladder; Invitrogen).

The rapid detection of MβL-producing isolates could be helpful for epidemiological purposes and for monitoring the emergence of MβL-producing isolates in clinical settings. The detection of such isolates could help rapidly establish standards for hospital infection control measures to minimize the spreading of these resistant determinants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Timothy R. Walsh, Mark A. Toleman, Yoshichika Arakawa, and Yunsop Chong for providing some of the MβL-harboring clinical isolates included in this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 November 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahar, G., A. Mazzariol, R. Koncan, A. Mert, R. Fontana, G. M. Rossolini, and G. Cornaglia. 2004. Detection of VIM-5 metallo-β-lactamase in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate from Turkey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:282-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castanheira, M., M. A. Toleman, R. N. Jones, F. J. Schmidt, and T. R. Walsh. 2004. Molecular characterization of a β-lactamase gene, blaGIM-1, encoding a new subclass of metallo-β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4654-4661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Castanheira, M., R. E. Mendes, R. C. Pição, F. P. Pinto, A. M. O. Machado, T. R. Walsh, and A. C. Gales. 2006. Abstr. 46th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C1-63, p. 72. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 3.Chu, Y. W., M. Afzal-Shah, E. T. Houang, M. I. Palepou, D. J. Lyon, N. Woodford, and D. M. Livermore. 2001. IMP-4, a novel metallo-β-lactamase from nosocomial Acinetobacter spp. collected in Hong Kong between 1994 and 1998. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:710-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Silva, G. J., M. Correia, C. Vital, G. Ribeiro, J. C. Sousa, R. Leitao, L. Peixe, and A. Duarte. 2002. Molecular characterization of blaIMP-5, a new integron-borne metallo-β-lactamase gene from an Acinetobacter baumannii nosocomial isolate in Portugal. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Docquier, J. D., M. L. Riccio, C. Mugnaioli, F. Luzzaro, A. Endimiani, A. Toniolo, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2003. IMP-12, a new plasmid-encoded metallo-β-lactamase from a Pseudomonas putida clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1522-1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galani, I., M. Souli, Z. Chryssouli, D. Katsala, and H. Giamarellou. 2004. First identification of an Escherichia coli clinical isolate producing both metallo-β-lactamase VIM-2 and extended-spectrum β-lactamase IBC-1. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10:757-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gales, A. C., L. C. Menezes, S. Silbert, and H. S. Sader. 2003. Dissemination in distinct Brazilian regions of an epidemic carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing SPM metallo-β-lactamase. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:699-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lartigue, M. F., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2004. First detection of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing metalloenzyme in an Enterobacteriaceae isolate in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4929-4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee, K., J. H. Yum, D. Yong, H. M. Lee, H. D. Kim, J. D. Docquier, G. M. Rossolini, and Y. Chong. 2005. Novel acquired metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaSIM-1, in a class 1 integron from Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates from Korea. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4485-4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libisch, B., M. Gacs, K. Csiszar, M. Muzslay, L. Rokusz, and M. Fuzi. 2004. Isolation of an integron-borne blaVIM-4 type metallo-β-lactamase gene from a carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate in Hungary. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3576-3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincopan, N., J. A. McCulloch, C. Reinert, V. C. Cassettari, A. C. Gales, and E. M. Mamizuka. 2005. First isolation of metallo-β-lactamase-producing multiresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from a patient in Brazil. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:516-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luzzaro, F., J. D. Docquier, C. Colinon, A. Endimiani, G. Lombardi, G. Amicosante, G. M. Rossolini, and A. Toniolo. 2004. Emergence in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae clinical isolates of the VIM-4 metallo-β-lactamase encoded by a conjugative plasmid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:648-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendes, R. E., M. Castanheira, P. Garcia, M. Guzman, M. A. Toleman, T. R. Walsh, and R. N. Jones. 2004. First isolation of blaVIM-2 in Latin America: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1433-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendes, R. E., M. A. Toleman, J. Ribeiro, H. S. Sader, R. N. Jones, and T. R. Walsh. 2004. Integron carrying a novel metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaIMP-16, and a fused form of aminoglycoside-resistant gene aac(6′)-30/aac(6′)-Ib′: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4693-4702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osano, E., Y. Arakawa, R. Wacharotayankun, M. Ohta, T. Horii, H. Ito, F. Yoshimura, and N. Kato. 1994. Molecular characterization of an enterobacterial metallo-β-lactamase found in a clinical isolate of Serratia marcescens that shows imipenem resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:71-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinteira, S., J. C. Sousa, and L. Peixe. 2005. Characterization of In100, a new integron carrying a metallo-β-lactamase and a carbenicillinase, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:451-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riccio, M. L., N. Franceschini, L. Boschi, B. Caravelli, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. Characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of blaIMP allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riccio, M. L., L. Pallecchi, J. D. Docquier, S. Cresti, M. R. Catania, L. Pagani, C. Lagatolla, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, and G. M. Rossolini. 2005. Clonal relatedness and conserved integron structures in epidemiologically unrelated Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains producing the VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase from different Italian hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:104-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sader, H. S., M. Castanheira, R. E. Mendes, M. Toleman, T. R. Walsh, and R. N. Jones. 2005. Dissemination and diversity of metallo-β-lactamases in Latin America: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 25:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Sader, H. S., R. Morfin, E. Rodriguez-Noriega, L. M. Deshpande, T. R. Walsh, R. N. Jones. 2005. Abstr. 45th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C2-99, p. 86. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 20.Scoulica, E. V., I. K. Neonakis, A. I. Gikas, and Y. J. Tselentis. 2004. Spread of blaVIM-1-producing E. coli in a university hospital in Greece. Genetic analysis of the integron carrying the blaVIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase gene. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 48:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tognim, M. C., A. C. Gales, A. P. Penteado, S. Silbert, and H. S. Sader. 2006. Dissemination of IMP-1 metallo-β-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter species in a Brazilian teaching hospital. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 27:742-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toleman, M. A., D. Biedenbach, D. Bennett, R. N. Jones, and T. R. Walsh. 2003. Genetic characterization of a novel metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaIMP-13, harboured by a novel Tn5051-type transposon disseminating carbapenemase genes in Europe: report from the SENTRY worldwide antimicrobial surveillance programme. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:583-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toleman, M. A., D. Biedenbach, D. M. Bennett, R. N. Jones, and T. R. Walsh. 2005. Italian metallo-β-lactamases: a national problem? Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toleman, M. A., K. Rolston, R. N. Jones, and T. R. Walsh. 2004. blaVIM-7, an evolutionarily distinct metallo-β-lactamase gene in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate from the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:329-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toleman, M. A., A. M. Simm, T. A. Murphy, A. C. Gales, D. J. Biedenbach, R. N. Jones, and T. R. Walsh. 2002. Molecular characterization of SPM-1, a novel metallo-β-lactamase isolated in Latin America: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh, T. R. 2005. The emergence and implications of metallo-β-lactamases in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11(Suppl. 6):2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh, T. R., M. A. Toleman, L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2005. Metallo-β-lactamases: the quiet before the storm? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:306-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan, J. J., W. C. Ko, and J. J. Wu. 2001. Identification of a plasmid encoding SHV-12, TEM-1, and a variant of IMP-2 metallo-β-lactamase, IMP-8, from a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2368-2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yum, J. H., K. Yi, H. Lee, D. Yong, K. Lee, J. M. Kim, G. M. Rossolini, and Y. Chong. 2002. Molecular characterization of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter genomospecies 3 from Korea: identification of two new integrons carrying the blaVIM-2 gene cassettes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:837-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]